Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Technology Use in the Classroom: Preferences of

Management Faculty Members

Joy V. Peluchette & Kathleen A. Rust

To cite this article: Joy V. Peluchette & Kathleen A. Rust (2005) Technology Use in the

Classroom: Preferences of Management Faculty Members, Journal of Education for Business, 80:4, 200-205, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.80.4.200-205

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.4.200-205

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 95

View related articles

lthough faculty members have a range of technology choices at their disposal, very little is known about their preferences and the factors that may influence or limit their choice (Dusick, 1998; Frost & Fukami, 1997; Grasha & Yangarber-Hicks, 2000; Spotts, 1999). This is particularly true in the business disciplines. Instead, researchers have tended to focus on faculty perceptions of particular instructional technologies (Boose, 2001; Piotrowski & Vodanovich, 2000; Seay, Rudolph, & Chamberlain, 2001) or on student learning and satisfac-tion with certain technologies (Arbaugh, 2000; Driver, 2002).

Our purpose in this study was to examine faculty preferences for various instructional technologies in undergrad-uate management courses. We believe that this assessment could help faculty members at schools of business better understand factors that may influence faculty use of technologies and identify factors that faculty members believe limit their teaching effectiveness with the use of technology. With this knowl-edge, education staff may be able to bet-ter use resources to serve the needs of both faculty members and students.

Instructional Technology Choices

Business faculty members have a wide range of technologies that they can

use to better, and in some cases replace, traditional teaching methods. For exam-ple, instructors may use lecture-enriching technology, such as Power-Point presentations, or take advantage of video conferencing to bring guest lecturers from distant places into the classroom. Instructors also can use computer-based technologies such as electronic mail, Web pages, chat rooms, and electronic bulletin boards in the classroom to facilitate communication between the instructor and student out-side the classroom. A number of com-puter simulations are now available for faculty members to use, providing a very real application of course material for students. In addition, in many schools of business, interactive

televi-sion (Seay et al., 2001) or Internet-based instruction is used in delivery of online courses (Boose, 2001; Driver, 2002). Although all of these technology options exist, there is little empirical evidence regarding how faculty mem-bers make choices between the various options that are available to them. What are some of the factors that influence or pose restrictions on their choices? Because of the limited research that has been done on this issue, we sought to undertake this exploratory study of the range of factors that, according to the literature results, may have an impact on how such choices are made.

Factors That Might Influence or Limit Technology Choice

For faculty members to use instruc-tional technology, they must be comfort-able with it and see it as a convenient and beneficial tool (Dusick, 1998; Reznich, 1997; Spotts, 1999). An instructor’s own feelings of competence, as well as his or her perception of student preferences in technology use, may influence the deci-sion on what type of technology should be used in the classroom (Grasha & Yan-garber-Hicks, 2000). Also, at many col-leges and universities, there is now an increased awareness of the importance of considering learning styles and student needs in course curriculum design (Papo,

Technology Use in the Classroom:

Preferences of

Management Faculty Members

JOY V. PELUCHETTE KATHLEEN A. RUST

University of Southern Indiana Elmhurst College Evansville, Indiana Elmhurst, Illinois

ABSTRACT.In this study, the authors investigated faculty members’ prefer-ences regarding the use of technologies as instructional tools in management courses. They mailed surveys to 500 management faculty members nation-wide; 124 were returned with usable data. Respondents indicated that course subject and classroom environmental factors did not affect their use of pre-ferred technologies; however, time con-straint was an issue for most of the fac-ulty members, particularly for women. Female faculty members were also more likely than their male colleagues to see their perception of students’ learning style as limiting the effective use of their preferred instructional tech-nologies.

A

2001). Because technology mediums can play a major role in the classroom expe-rience, technology choice may be influ-enced by such learning style factors.

Demographics, such as a faculty member’s age, rank, or gender, also may influence technology use or choice of medium. For example, Rosseau and Rogers (1998) found that older faculty members used fewer technology applica-tions. Likewise, more senior faculty members who are tenured may be less motivated to learn new technologies or feel less competent in using instructional technologies. Recent research has also revealed that there may be gender differ-ences in the way that faculty members use technology and rate their levels of knowledge or expertise (Spotts, 1999). For example, in a study of 367 faculty members at a medium-sized institution, men rated their knowledge of and exper-tise in instructional technology higher than women did, but both genders had similar frequencies of technology use (Spotts, Bowman, & Mertz, 1997). Campbell and Varnhagen (2002) found that women faculty members, because of their tendency to explore more relational approaches to teaching, use educational technologies for purposes different from those of their male colleagues. Thus, gender differences in both perceptions and uses of technology are worth further investigation.

In addition, the level of institutional support can play a key role in the use of technology (Boose, 2001; Spotts, 1999). In some instances, faculty members may wish to use certain forms of instructional technology (e.g., multimedia support in the classroom), but their institutions do not have sufficient resources to meet their needs. Related to institutional sup-port is the issue of technical supsup-port. Faculty members indicate that technical problems such as slow systems and soft-ware or server problems are important factors in determining how or whether they decide to use certain instructional technologies (Hantula, 1998; Piotrowski & Vodanovich, 2000). Papo (2001), for example, indicated that faculty frustra-tion with slow equipment delivery, equipment set-up time, and limited fund-ing for technology upgrades can foster a reluctance to use instructional media. In other situations, faculty members may

feel pressured by their institutions to use certain technologies (e.g., interactive television delivery or Internet-based instruction) and may have mixed feelings about whether they have received ade-quate training and whether such tech-nologies are appropriate (Bocchi, East-man, & Swift, 2004). Such issues will become more important as schools of business face increasing pressure from both their institutions and their accredit-ing agencies to incorporate technology-enhanced instruction (Driver, 2002).

Course subject may influence the choice of technology used to support the learning experience. Decisions on what types of technology to use for a particu-lar course are likely to be influenced by the instructor’s learning objectives, as well as what textbook publishing compa-nies may have designed and developed for the course subject. For example, many faculty members now use a com-puter simulation in strategic management courses because they believe that the simulation provides a more realistic set of scenarios for students in making strategic business decisions. Likewise, those teaching production and operations management might use the computer in class to show students how to solve prob-lems using Excel spreadsheets.

Class size also can influence the type of technology used in a course. It may be possible to enhance the learning experience of classes with large student enrollments through technology. For example, using videos and PowerPoint presentations to support the lecture teaching method in large classes helps to provide visual support to the learning experience. Similarly, the use of chat rooms and electronic bulletin boards may assist student groups in working together on assignments in large classes (Papo, 2001). Class size also may serve to limit the use of technology in some courses. For example, the instructor’s preference may be to have each student seated at a computer terminal during class, but this may not be possible if class enrollment exceeds the facility space in computer teaching labs. Large course enrollments can hinder the effec-tiveness of online instruction and the use of e-mail or discussion boards for classroom support. A nationwide survey cited in a recent article in The Chronicle

of Higher Education stated that, when asked about their attitudes and experi-ence with distance education, faculty members indicated that they were hap-piest when teaching online courses for which there were enrollment limits (Carr, 2000). Likewise, Bocchi et al. (2004) argued for the importance of low enrollments (20 students or fewer) for effective distance education in online MBA instruction.

The use of some forms of instruction-al technology requires substantiinstruction-al time, either in terms of course development, course management, or maintaining one’s currency with the technology (Boc-chi et al., 2004). These time constraints may result from the faculty member’s other teaching, research, service, or administrative responsibilities. Although in recent studies investigators have begun to question the time difference expended with certain instructional technologies (Hilsop & Ellis, 2004), substantial em-pirical evidence indicates that time con-straint is a major drawback to faculty use of instructional technology (Hulbert & McBride, 2004; Vannatta & Fordham, 2004; Vodanovich & Piotrowski, 1999, 2001).

Method

The sample for this study consisted of full-time faculty members in the area of management from colleges and univer-sities across the United States. Using the Directory of Management Faculty (Hasselback, 2001), we drew up a strat-ified sample (by rank) from randomly selected institutions. Of the 500 ques-tionnaires mailed, 126 were returned, producing a response rate of 25.2%. Because 2 of the returned surveys had missing data, we used only 124 of the questionnaires for data analysis. Of the 124 participants, 65% were men and 35% were women. Nineteen percent of the respondents had the rank of assistant professor, 34% were associate profes-sors, and 39% were full professors. Of the sample, 67% had been teaching for at least 11 years, and 57% had been at their current institutions for 11 years or more. Nearly half of the faculty mem-bers taught primarily in the areas of strategic management (25%) and orga-nizational behavior (20%), with the

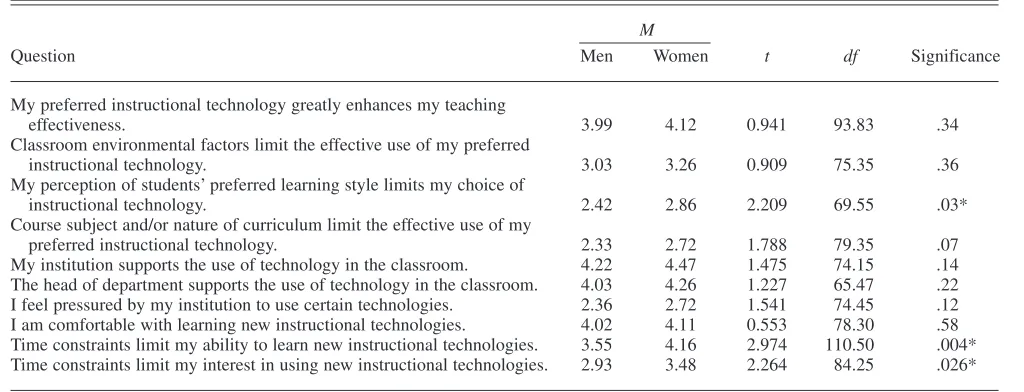

ceived as influencing or limiting their choices of teaching methods. Our results showed that 77% of the respon-dents agreed that their preferred instruc-tional technologies greatly enhanced their teaching effectiveness. Eighty-three percent indicated that they were comfortable with learning new tech-nologies. Course subject did not appear to be a limiting factor for most faculty members (66%) in their use of preferred technology, and classroom environmen-tal factors received mixed results as a limiting factor. Only 25% of the respon-dents indicated that their perception of student learning needs influenced their choices of instructional technology. Almost 90% of the faculty members viewed their institutions as supporting the use of technology in the classroom, and 82% perceived such support from their department heads as well. Only about 25% of the respondents felt pres-sured by their institutions to use certain technologies. Time constraints were viewed by 75% of the faculty members as limiting their ability to learn new instructional technologies and by 50% as limiting their interest in using new technologies.

Class size did not appear to be a major consideration in faculty members’ pref-erences for technology use, except in the cases of respondents who used e-mail and Web pages or chat rooms and dis-cussion boards for instructional support. Large class size was found to have a sig-nificant negative correlation with e-mail and Web page use (r= –.376,p< .010) and with the use of chat rooms and dis-cussion boards (r = –.496, p < .012), indicating a preference for smaller num-bers of students in classes using these methods of technology. Notably, class size did not appear to be an issue for those teaching online courses. This find-ing could be attributed to the small num-ber of respondents who indicated a pref-erence for teaching courses in which such technology is used.

Results from t tests showed signifi-cant gender differences in instructional technology preferences for two of the technology options. Compared with male faculty members, female faculty members indicated a significant prefer-ence for the combined use of Power-Point and a whiteboard or blackboard,t remaining faculty members teaching an

assortment of other management disci-plines. The typical class size for 63% of the sample was 20–39, with 23% having larger classes of 40–59 students. Most faculty members indicated that, on aver-age, 75% of the students in their classes were of traditional age (18–24 years).

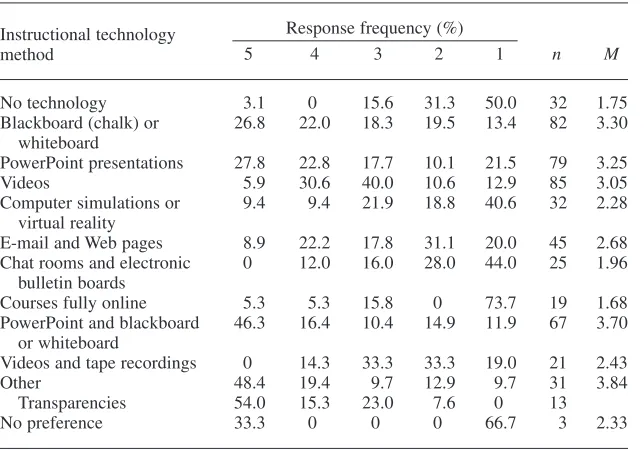

The questionnaire that we developed for our study contained three parts. In the first section of the survey, we asked par-ticipants to rank their preferred instruc-tional technologies (as shown in Table 1). In the second section of the survey, we asked participants to use a 5-point scale ranging from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree) to indicate the extent to which they perceived that various fac-tors influenced or limited their choices of instructional technology. In the final sec-tion, we requested demographic informa-tion, such as sex, rank, age, years of teaching, years at current institutions, and year that the respondents’ doctoral degrees were conferred. We asked addi-tional questions about the instructors’ main teaching areas, typical class sizes, and percentages of traditional students in typical classes.

Given the exploratory nature of this study, we used descriptive statistics to examine faculty instructional technology

preferences and their perceptions regard-ing factors that may influence or limit technology use. To examine the relation-ship between class size and the ranking of instructional technology preferences, we used Spearman rank correlations. Finally, we performed t tests to test for gender differences in preferences regard-ing instructional technologies and in per-ceptions of factors influencing or limit-ing use of technology.

Results

Our findings for use of instructional technology methods showed the strongest preference for methods other than those listed. The next strongest preferences were for “PowerPoint and blackboard or whiteboard” and “black-board or white“black-board.” In examining the survey questionnaires, we found that the item most frequently listed in the “other” category was overhead trans-parencies and use of overhead projector. Faculty members demonstrated the least preference for “courses fully online” and “no technology.” We provide descriptive statistics and mean values for these rankings in Table 1.

In Table 2, we present descriptive sta-tistics for factors that respondents per-TABLE 1. Instructional Technology Preferences of Faculty Members

Response frequency (%)

5 4 3 2 1 n M

No technology 3.1 0 15.6 31.3 50.0 32 1.75 Blackboard (chalk) or 26.8 22.0 18.3 19.5 13.4 82 3.30

whiteboard

PowerPoint presentations 27.8 22.8 17.7 10.1 21.5 79 3.25

Videos 5.9 30.6 40.0 10.6 12.9 85 3.05

Computer simulations or 9.4 9.4 21.9 18.8 40.6 32 2.28 virtual reality

E-mail and Web pages 8.9 22.2 17.8 31.1 20.0 45 2.68 Chat rooms and electronic 0 12.0 16.0 28.0 44.0 25 1.96

bulletin boards

Courses fully online 5.3 5.3 15.8 0 73.7 19 1.68 PowerPoint and blackboard 46.3 16.4 10.4 14.9 11.9 67 3.70

or whiteboard

Videos and tape recordings 0 14.3 33.3 33.3 19.0 21 2.43

Other 48.4 19.4 9.7 12.9 9.7 31 3.84

Transparencies 54.0 15.3 23.0 7.6 0 13

No preference 33.3 0 0 0 66.7 3 2.33

Note. Respondents rated their preferred methods on a scale ranging from 5 (most preferred) to 1 (least preferred).

Instructional technology method

using instructional technology and learn-ing new techniques. It is interestlearn-ing to note, however, that the technologies most strongly preferred by the faculty mem-bers are generally considered to be fairly “low tech” (overhead transparencies, PowerPoint, and blackboard and white-board). One possible reason for this find-ing may be that nearly half of the respon-dents taught either organizational behavior or strategic management, in both of which instructors tend to make extensive use of experiential learning or case analyses and student presentations. Because these learning methods do not lend themselves well to online teaching, only a few of the faculty members in our sample expressed a preference for online courses.

Although classroom environmental factors and course subject proved not to be strong factors in limiting the use of preferred technologies, large class size was a significant deterrent to the use of e-mail and Web pages as well as chat rooms and discussion boards. Most fac-ulty members also viewed time con-straints as a limiting factor in their abil-ity to learn and be interested in using new instructional technologies. This result was more pronounced among the female faculty members. Staff at institu-tions interested in encouraging the use of technology to aid instruction may find that faculty members will need sufficient release time to retool or learn new tech-nologies and should realize that class enrollment size might deter instructors from using certain technologies.

There were some interesting gender differences in our results. Compared with the women, the men in our sample showed a stronger preference for the use of no technology in the classroom. Does this finding indicate that they are less comfortable with using technology or do not see it as appropriate for the courses that they are teaching? Perceptions of students’ learning needs appeared to play a larger role in influencing use of instructional technology among the female faculty members. Could women faculty members be more perceptive of student learning needs and place greater weight on this factor in their use of tech-nology? These issues warrant further investigation.

In general, the management faculty = 2.132, p< .038. Compared with the

women, the men in our sample showed a significant preference for the use of no technology, t = –2.293, p < .03. We show these results in Table 3.

We also found gender differences in perceptions of factors that might influ-ence or limit use of instructional tech-nology (see Table 4). Our t test results showed that female faculty members were more likely than their male col-leagues to see their perception of stu-dents’ learning styles as limiting the effective use of their preferred instruc-tional technology, t = 2.20, p < .03. Female respondents were also more likely than their male colleagues to view

time constraints as limiting (a) their ability to learn,t= 2.97,p < .004, and (b) their interest in using,t= 2.26,p< .026, new instructional technologies.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate some interesting findings with regard to facul-ty use of instructional technology. Most of those surveyed clearly preferred using some form of technology, believed that their preferences enhanced their teaching effectiveness, and were comfortable with learning new technologies. These find-ings demonstrate a positive view on the part of faculty members with regard to TABLE 2. Faculty Perceptions of Situational Factors Affecting

Instructional Technology Use

Response frequency (%)

Question 5 4 3 2 1 n M

My preferred instructional technology greatly enhances

my teaching effectiveness. 28.2 49.2 21.0 1.6 0 124 4.04 Classroom environmental

factors limit the effective use of my preferred

instructional technology. 15.3 29.8 11.3 36.3 6.5 123 3.11 My perception of students’

preferred learning style limits my choice of

instructional technology. 0.8 24.2 14.5 51.6 8.1 123 2.58 Course subject and/or

nature of curriculum limit the effective use of my preferred instructional

technology. 4.8 20.2 7.3 51.6 14.5 122 2.48 My institution supports the

use of technology in the

classroom. 47.6 41.9 5.6 4.0 0.8 124 4.31 The head of department

supports the use of technology in the

classroom. 37.1 45.2 11.3 4.8 1.6 124 4.11 I feel pressured by my

institution to use certain

technologies. 8.1 16.1 8.1 52.4 15.3 124 2.49 I am comfortable with

learning new instructional

technologies. 29.8 53.2 8.1 8.1 8.1 123 4.05 Time constraints limit my

ability to learn new

instructional technologies. 29.8 45.2 1.6 16.1 6.5 123 3.76 Time constraints limit my

interest in using new

instructional technologies. 15.3 35.5 4.0 35.5 8.9 123 3.13

Note. Respondents rated the effect of situational factors on a scale with the following anchors: 5 (strongly agree), 4 (agree), 3 (unsure), 2 (disagree), and 1 (strongly disagree).

members in our study indicated strong institutional support for the use of instructional technology and believed that their department heads reinforced this support. Only 25% felt pressure from their institutions to use certain technologies, which is good news for staff at schools of business who are interested in supporting technology use for instruction.

REFERENCES

Arbaugh, J. (2000). An exploratory study of the effects of gender on student learning and class participation in an Internet-based MBA course. Management Learning, 31(4), 503–519. Bocchi, J., Eastman, J., & Swift, C. (2004).

Retaining the online learner: A profile of stu-dents in an online MBA program and

implica-tions for teaching them. Journal of Education for Business, 79(4), 245–253.

Boose, M. (2001). Web-based instruction: Success-ful preparation for course transformation. Jour-nal of Applied Business Research, 17(4), 69–81. Campbell, K., & Varnhagen, S. (2002). When fac-ulty use instructional technologies: Using Clark’s delivery model to understand gender differences. Canadian Journal of Higher Edu-cation, 32(1), 31–56.

Carr, S. (2000, July 7). Many professors are opti-mistic on distance learning, survey finds. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 46(44), A35. Driver, M. (2002). Investigating the benefits of

Web-centric instruction for student learning: An exploratory study of an MBA course. Journal of Education for Business, 77(4), 236–246. Dusick, D. (1998). What social cognitive factors

influence faculty members’ use of computers for teaching? A literature review. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 31(2), 123–138.

Frost, P. J., & Fukami, C. V. (1997). Teaching

effectiveness in the organizational sciences: Recognizing and enhancing the scholarship of teaching. Academy of Management Journal, 40(6), 1271–1281.

Grasha, A. F., & Yangarber-Hicks, N. (2000). Inte-grating teaching styles with instructional tech-nology. College Teaching, 48(1), 2–10. Hantula, D. (1998). The virtual

industrial/organi-zational psychology class: Learning and teach-ing in cyberspace in three iterations. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 30,205–216.

Hasselback, J. R. (2001). Directory of manage-ment faculty. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Irwin. Hilsop, G., & Ellis, H. (2004). A study of faculty

effort in online teaching. Internet & Higher Education, 7(1), 15–32.

Hulbert, L., & McBride, R. (2004). Utilizing videoconferencing in library education: A team teaching approach. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 45(1), 26–35. Papo, W. (2001). Integration of educational media

in higher education large classes. Education TABLE 3. Results of ttests for Gender Differences in Instructional Technology Preferences

n M

Instructional technology method Men Women Men Women t df Significance

No technology 21 10 2.00 1.30 –2.293 25.23 .03*

Blackboard (chalk) or whiteboard 59 23 3.37 3.08 –0.814 38.82 .42

PowerPoint presentations 54 24 3.24 3.20 –0.090 46.95 .92

Videos 54 30 2.92 3.26 1.465 70.19 .14

Computer simulations or virtual reality 24 8 2.25 2.37 0.262 16.51 .79

Email and Web pages 29 16 2.82 2.43 –1.09 40.91 .28

Chat rooms and electronic bulletin boards 16 9 1.68 2.44 1.49 10.25 .16

Courses fully online 12 7 1.75 1.57 –0.324 16.37 .75

PowerPoint and blackboard or whiteboard 43 23 3.46 4.21 2.132 52.16 .03*

Videos and tape recordings 14 7 2.28 2.71 0.959 12.61 .35

Other 23 8 4.00 3.37 –1.03 11.39 .32

*Significant at .05 level.

TABLE 4. Gender Differences in Faculty Perceptions of Factors Influencing Instructional Technology Use

M

Question Men Women t df Significance

My preferred instructional technology greatly enhances my teaching

effectiveness. 3.99 4.12 0.941 93.83 .34

Classroom environmental factors limit the effective use of my preferred

instructional technology. 3.03 3.26 0.909 75.35 .36

My perception of students’ preferred learning style limits my choice of

instructional technology. 2.42 2.86 2.209 69.55 .03*

Course subject and/or nature of curriculum limit the effective use of my

preferred instructional technology. 2.33 2.72 1.788 79.35 .07 My institution supports the use of technology in the classroom. 4.22 4.47 1.475 74.15 .14 The head of department supports the use of technology in the classroom. 4.03 4.26 1.227 65.47 .22 I feel pressured by my institution to use certain technologies. 2.36 2.72 1.541 74.45 .12 I am comfortable with learning new instructional technologies. 4.02 4.11 0.553 78.30 .58 Time constraints limit my ability to learn new instructional technologies. 3.55 4.16 2.974 110.50 .004* Time constraints limit my interest in using new instructional technologies. 2.93 3.48 2.264 84.25 .026*

*Significant at .05 level.

Media International, 38(2/3), 95–99. Piotrowski, C., & Vodanovich, S. (2000). Are the

reported barriers to Internet-based instruction warranted? A synthesis of recent research. Edu-cation, 121(1), 48–53.

Reznich, C. (1997). A survey of medical school clinical faculty to determine their computer use and needs for computer skills training. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL. Rosseau, G., & Rogers, W. (1998). Computer

usage patterns of university faculty members across the lifespan. Computers in Human

Behavior, 14,417–428.

Seay, R., Rudolph, H., & Chamberlain, D. (2001). Faculty perceptions of interactive television instruction. Journal of Education for Business, 77(2), 99–106.

Spotts, T. (1999). Faculty use of instructional technology in higher education: Profiles of con-tributing and deterring factors. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 59(10-A), 3738. Spotts, T., Bowman, M., & Mertz, C. (1997).

Gen-der and use of instructional technologies: A study of university faculty. Higher Education,

34(4), 421–436.

Vannatta, R., & Fordham, N. (2004). Teacher dis-positions as predictors of classroom technology use. Journal of Research on Technology in Edu-cation, 36(3), 253–271.

Vodanovich, S., & Piotrowski, C. (1999). Views of academic I-O psychologists toward Internet-based instruction. The Industrial-Organizational Psychologist, 37(1), 52–55.

Vodanovich, S., & Piotrowski, C. (2001). Internet-based instruction: A national survey of psychol-ogy faculty. Journal of Instructional Psycholpsychol-ogy, 28(4), 253–256.