See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229009657

The social ecology of movement, environment

and community (MEC)

ARTICLE

READS

39

10 AUTHORS, INCLUDING:

Rosemary Bennett

Monash University (Australia)

2PUBLICATIONS 0CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Geraldine Burke

Monash University (Australia)

3PUBLICATIONS 6CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Justen O'Connor

Monash University (Australia)

20PUBLICATIONS 87CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Terri-Anne Philpott

Monash University (Australia)

3PUBLICATIONS 0CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

The social ecology of movement,

environment and community (MEC)

Phillip Payne (Convenor), Rosemary Bennett, Trent Brown, Geraldine

Burke, Amy Cutter-Mackenzie, Justen O’Connor, Terri-Anne Philpott,

Laura Ward, Brian Wattchow and Wynn Shooter.

AARE Conference

‘Changing Climates: Education for Sustainable Futures’

30 November – 4 December 2008

Table of Contents

Introduction ...4

Paper 1: The concept of movement and its social ecology...5

Paper 2: Environment, place and social ecology in educational practice ...18

Paper 3: The concept of community and its social ecology ...36

Paper 4: A social ecology of movement, environment and community ...47

MEC Members ...57

Additional information about MEC...59

MEC platforms...59

Further information ...61

Key contacts ...62

Introduction

The Movement, Environment and Community (MEC) research group emerged in 2007 as a result of the reconceptualization of our undergraduate programs in Sport and Outdoor Recreation (SOR) and Monash University’s development of the ‘Health, Inclusion and Sustainable Living Precinct’ at the Peninsula Campus. The close relationship between MEC and SOR is an example of ‘research-led-teaching’ and ‘education-led-research’ and is illustrated on the inside back cover.

MEC members are listed on page 57. Members includes academic staff from Sport and Outdoor Recreation, the Faculty of Education and others, including Higher Degree by Research candidates. MEC enjoys close relationships with colleagues in the Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash’s Tourism Research Institute, Monash Sustainability Institute and the Monash Initiative on Obesity.

The MEC identity, research and teaching are a bold development that combines different theoretical perspectives, pedagogical understandings and approaches to inquiry and methodological development. Our platform is detailed on page 59. Our work has particular relevance to the education sector, including physical, outdoor, health, environmental and experiential educations.

The 2008 AARE conference theme of Changing Climates: Education for Sustainable Futures provides a timely opportunity for MEC researchers to outline a bold, innovative direction we believe is worth pursuing. The following papers focus on the conceptual framing of movement, environment and community and some of the pedagogical issues they imply. Other work currently being undertaken by MEC focuses on the socio-cultural and ecological issues surrounding pedagogy, development and policy and related research challenges and directions.

Associate Professor Phillip Payne

Research Leader, Movement, Environment and Community (MEC).

Paper 1: The concept of movement and its social ecology

*Trent D. Brown and Phillip G. Payne

Introduction

There is a need in educational discourse for the development of qualities and characteristics of the

body in movement that posits a more intrinsic and subjective value of physical activity. In physical

education, sport, outdoor, environmental, health and experiential education such concepts of movement and

alternative pedagogical practices require more earnest theoretical/practical deliberation and discussion.

Movement is basic to bodily experience but the qualities and characteristics of the ‘body moving’ in

environments are not well appreciated in the current education literature and health promotion discourses.

At the root of this lack of understanding is the persistent subordination in the western mindset of the body.

The lack of understanding about the moving body also serves to undermine how ‘movers’ make

meaning of their bodily movements according to the spaces and places of that movement. If so, ‘learning’ in

and through movement, as is demanded in schools and community settings are also undermined. Put

differently, and bluntly, any physical education pedagogy that does not engage seriously with the concept of

movement, its qualities and characteristics in experience diminishes the educational prospects and

pedagogical potential of the field of physical education. But physical education in schools, and

coaching/fitness training in the community, are examples only. The challenge for healthy, sustainable living

lies partially in the promotion of movement experiences in a wide range of human endeavour and, in

schools, in a broad range of curriculum areas.

For the purposes of this paper, the specific challenge for teacher education research is to develop

philosophical, theoretical and empirical understandings about the centrality of movement experiences so that

future educators and professionals concerned about the sustainability of health and wellbeing promotion can

critically examine their current practices and policies. We believe a revitalized notion of movement, and

understanding of the various contexts and environments in which movement occurs, will enable deeper

consideration of how the discourses of physical education, human movement and outdoor education can be

reconceptualized in school-based pedagogies and related community development initiatives in sports and

outdoor recreations.

In this paper, we focus on the qualities and intricacies of movement and therefore their potential

contribution to the education of the practitioner, be it physical/outdoor education teacher, recreation planner

or health promotion professional. Drawing upon the phenomenology of movement in physical education, it

is timely that we extract from that literature the ‘other’ qualities, characteristics and different or ‘wild’

dimensions of movements that escape mention in the dominant physical education discourses.

Our purpose is the revitalisation of movement and movement education which may partially

rhetoric about lifestyle diseases such as the obesity epidemic, and the escalation of diabetes, physical

inactivity and sedentary behaviours and disengagement in schools. The task that we are undertaking in the

Movement, Environment and Community (MEC) research node is to locate the ‘marginalised’ literature

about movement and movement experiences in physical education into a broader, non-reductionist

theoretical framework of social ecology and pedagogical platform of experiential education that informs

pedagogical and curriculum inquiry and critical research development. Notwithstanding the literature about

movement that is readily available in, for example, philosophy, social theory, geography and cognitive

science,1 our initial but limited aim here is to outline a concept of movement and its ‘lived’ experiential and

phenomenological contexts as part of what we believe is a distinctive notions of ‘spatialisation of

movement’ and ‘geography of physical activity.’

That is, our interest in MEC is to locate this ‘geography of physical activity’ within the formulation

of a ‘social ecology’ of movement education and health and wellbeing promotion. In doing so, MEC

researchers aim to make a unique contribution to physical, outdoor, health, environmental and experiential

education discourses. While this paper focuses primarily on the concept of movement within MEC it

gestures to the E- environmental and C – community concepts that our MEC colleagues will address in more

detail in the following papers.

Movement, meaning-making and their concepts

There is renewed interest in the discourse of physical education about the concepts of movement,

movement experiences, meaning and meaning-making as they relate to the pedagogies of the body (Arnold,

1979; Brown, 2008; Kentel & Dobson, 2007; Kretchmar, 2007). While the literature in physical education

has not been abundant, that which has been available for four decades is conceptually rich and has provided

untapped intellectual resources for theoretical development of a phenomenology of movement. This

revitalised interest in ‘meaning in movement’, ‘physical literacy’, ‘movement literacy’, ‘somatic education’

or ‘movement culture’ is partially in response to the lack of understanding of the rich notions of lived bodily

experiences and meaning-making that are absent in the discourses of sport (Kirk, 2003) or fitness and public

health (Trost, 2004).

Scholars working with phenomenological approaches and critical perspectives of physical education

have suggested that this response may also be due to:

1 Meaning and meaning-making in movement draws mainly on concepts from diverse academic fields including

a) research suggesting that students derive little meaning and satisfaction from physical activity during

physical education (Carlson, 1995; Tinning & Fitzclarence, 1992);

b) understanding student motivation to alleviate the so-called childhood obesity and physical inactivity

‘epidemics’ (Kentel & Dobson, 2007; Kretchmar, 2007);

c) humanistic and philosophical interest in elucidating the richer ‘lived experience’ dimensions of

movement (Kleinman, 1979) or to address the importance of movement in self understanding about

what it means to be human;

d) to further elucidate and acknowledge that movement is inextricably linked to the environment through

the ‘body spatialisation’ and ‘geographies of movement;’ and

e) to different layers of communities (school, neighbourhood, town) as the ‘drivers’ of building social

and environmental capital which enables healthy sustainable living through upstream approaches

(Sallis et al., 2006).

To introduce the complexities of the concepts of meaning, meaning-making and lived experience in

‘movement’ we refer readers to publications that might be described as seminal such as Connotations of

Movement in Sport and Dance (Metheny, 1965), Meaning in Movement (Metheny, 1968), Philosophy and

Human Movement (Best, 1978), Sport and the Body: a philosophical symposium (Gerber & Morgan, 1979),

Meaning in Movement, Sport and Physical Education (Arnold, 1979) and Practical Philosophy of Sport and

Physical Activity (Kretchmar, 2005).

In briefly synthesizing these authors, the notion of movement/physical activity/sport as a worthwhile

pursuit in and of itself is ever-present. Additionally, from a phenomenological perspective the personal

associations of distinctive, pleasing and bodily related contexts enable for an increased understanding of

one’s embodied consciousness. There has been tacit recognition in these publications of the now

popularized notions in educational and pedagogical discourses of different ‘ways of knowing’ and ‘authentic

learning’. To highlight more concretely the meaning(s) of movement and meaning-making in physical

education and sport we draw, for illustrative purposes on three meaning-making concepts: a) the denotations

and connotations of movement (Metheny, 1965, 1968); b) the concept of education ‘in’ movement (Arnold,

1979); and c) Kretchmar’s (2000) description of meaning-making, whereby an individual is moved ‘away’,

moved ‘toward’ and moved ‘along’. These scholars’ interpretations of movement and meaning-making

have been chosen based on (i) the word/time limits on this article; (ii) in response to frequency of these

citations within the literature and (iii) as succinct and interpretable approaches in providing descriptions of

the importance of the intrinsic qualities of movement.

Historically, it is likely that van den Berg’s (1952) article on the Human body and the significance

of human movement was the first to highlight the importance of phenomenological concepts as they related

to human movement. This philosophical work draws on early phenomenologists, Maurice Merleau-Ponty

and Jean-Paul Sartre. The concepts of (i) landscape of action, (ii) intention of the moving person, and (iii)

the glance of the other are consistently described in various ways by authors such as Metheny (1968),

and Dobson (2007), Quennerstedt (2008) and Brown (2008) who have also contributed to the

phenomenological work and importance of meaning-making within the domain of physical education2. We

wish now to provide a vignette that provides a description of ‘intrinsic qualities’ associated with movement

before examining various descriptions of meaning-making as presented by Metheny, Arnold and Kretchmar.

This was it then. I straddled the saddle, planted my feet on the pedals, Chris steadying me, then a forward thrust and the bike started rolling down the slight incline of Dudley Road on the hump of the camber, gathering speed, Chris running along behind. I knew the set of the hill from the manic descents on the trike, and feel of the pedals under my toes was familiar, too, but suddenly I realized that an entirely new sensation was coursing through me. I was riding free. Balancing unaided. Chris had let go of the saddle and left me to natural instinct and providence. Brakes? Fat chance, but stopping didn’t signify, motion did…the thrill, the exhilaration was unimaginable then, but it has stayed with me ever since…I turned back radiant with glee and rode up to where Chris stood with a big grin on his face, sharing in my triumph. I was a cyclist, a skeddadler (Fife, 2008, p.19).

How likely is it to find these sensibilities mentioned in the official physical education curriculum?

Fife highlighted for us the more pure experience of movements and its spatial and temporal

affordances – hence our enthusiasm for a ‘spatiality of movement’ and ‘geography of physical activity’ as

more primordial/primitive elements that require revitalization in the physical education/sport discourses,

where an instrumental, competitive, performative discourse is unquestionably privileged. For the author,

Graeme, riding a bike for the first time unaided was a lived, felt, sentient, purposive act (Shusterman, 2008).

For Metheny (1968) meaning derives from the denotations, the literal meaning, and connotations, the

personal associations as it has to do with movement, sport and physical activity. Importantly for physical

education teachers it is the connotations of movement forms that provide the richness of meanings, hence the

meaning-making for the individual. In this example Graeme denotatively cycled from point A to point B,

albeit down a road with a hill, but this movement for Graeme at least was connotatively complex. His

narrative description is interesting and tells us something about who he is, what he wishes and hopes for

when cycling and what meaning he attaches to cycling. Clearly the feeling of riding a bicycle unaided is a

lifelong pleasurable, delightful and memorable experience, it was perhaps Graeme’s ‘first rush of

movement’ (Smith, 2007). According to Metheny in Kretchmar (2000) not all connotations are personal or

distinctive, in fact they may be common to a particular time and culture, in other words socio-culturally

constructed. As Roberts (2008) and Ryan and Rossi (2008) and cautioned:

meaning-making that is regarded as exclusively socially constructed does not account for the varied and often contradictory perspectives that an individual simultaneously takes up and rejects, yet theories that consider meaning-making to be based only on individual psychology neglect to explain the influence of the social milieu on any verbal or non verbal interaction. (p. 40)

Whilst a tension between the individual and social appears to exist, for Metheny this was not a

problem for it created opportunity for researchers and practitioners to address the complex meanings of

2

movement between the personal and the cultural. In signalling towards our colleagues presenting ‘The

concept of environment and its social ecology’ (Wattchow, Burke and Cutter-MacKenzie, 2008) and ‘The

concept of community and its social ecology’ (O’Connor, 2008) the cultural connotations of movement, and

if we look broader at the environment and community, contribute to this meaning-making primarily through

reinforced rituals, values, truths that occur in ‘places’ (environment) and shared ‘spaces’ (community) with

family/friends or individuals as members of sporting clubs.

Education ‘in’ movement are those activities of movement/physical activity that are worthwhile in

and of themselves from the perspective of the moving agent. They are important educationally as they allow

the moving agent to actualise themselves in distinctive, pleasing and bodily related contexts as a process of

understanding their own embodied consciousness. These perspectives are subjective and a

‘good-in-themselves’ as well as being ‘good-for-me’. Additionally to further elucidate the meanings in sport,

movement and physical education, Arnold (1979) proposed three subjective movement meaning categories:

primordial meanings, contextual meanings and existential meanings. Primordial meaning, according to

Arnold, relates to how the performer is not only being aware and of experiencing a movement itself, but also

to the subjective attaching some value to it. In other words it is related to kinaesthesis, bodily experience

and self-identity and the experiences that a performer has that are uniquely his/her own and may, or may not,

be able to give voice to, noting the limitations of an overt focus on just the individual at the expense of

cultural understanding. Contextual meaning provides the performer with meanings in movement when

performed in a specific type of movement situation. The example that Arnold uses here is: (a) sports’ skills

as particular instances of contextual meanings, for example the ‘leg glance’ only has meaning in cricket.

Contextual meaning as it relates to sport skills means that techniques need to be acquired, but also the skills

need to be utilised in the appropriate context of the game or movement; and (b) sports as rule-bound social

realities, for example, when playing soccer I learn skills of kicking and trapping. But I also learn the

soccer-bound skills of ‘offside’ and ‘to lay off the ball’. As these rules relate to soccer others that play the game

also agree to abide by them. Whilst this creates common ground, there is some overlap between what I

derive from such contextual meaning as someone else does. Hence contextual meaning is both rule-bound

and social. Finally, existential meanings in movement relate to those individual and personal meanings that

are part of who I am in the world. For Arnold these themes are: (a) the existent as agent, (b) sport as a quest

for authentic experience, and (c) dimensions of existential meaning in sport.

The final interpretation that we wish to draw upon from the physical education literature is the

concepts of being moved ‘away’, ‘toward’ and ‘along’ (Kretchmar, 2000). According to Kretchmar

“meaning can transport individuals away from the literal features of an event – the movements themselves,

their biomechanical requirements, perhaps even the score of a game” (p. 22). This definition highlights how

movement/sport/physical activity becomes meaningful. It does so by moving you away from the mundane

tasks of everyday life, to a place that is uplifting and where positive, joyful, delightful memories come to the

fore. Meaning can also be derived when individuals are drawn toward particulars of movement. The

some they become part of the environment, or piece of equipment they are using. Examples to highlight

being moved toward include rock climbers become part of the rock they are climbing (Csikszentmihalyi,

1977), or rowers toward the water, boat or fellow rowers (Lambert, 1998). We offer caution, especially to

physical educators that may have used or comprehend this concept of meaning-making in movement.

Exercise can at times be detrimental, and some performers that become exercise dependent plausibly do

more harm than good when their meaning-making ‘takes’ over their lives. Finally the third kind of

meaning-making experience is one which Kretchmar described as being moved along. Physical

activity/movement can become very meaningful when it is described as a storyline or narrative in one’s life.

From the performer’s perspective it is viewed as a spiritual and philosophical approach to life which is

clearly at odds with thoughts within the current discourses of physical education about fun, exercise and skill

development as meaningful content. As an example, Kretchmar drew on Henry David Thoreau (1966/1982)

book chapter on thoughts on walking (sauntering as described by Thoreau). Describing it as a fundamental

part of who he was, sharing his hopes, plans and actions. His action of walking, being moved along was an

important part of the meaning-making movement experience of who he was and how it was part of his life’s

narrative.

In summarizing this brief introduction into meaning-making concepts of movement within the

discourses of physical education as presented by Metheny, Arnold and Kretchmar are the personal

associations of distinctive, pleasing and bodily related contexts enabling an increased understanding of one’s

embodied consciousness. Whilst some suggest that this personal phenomenological approach is limited

(Roberts, 2008), it never the less opens up opportunities for physical education teachers and researchers to

understand the important subjective and ‘intrinsic’ qualities of movement of the individuals, that are both

personal and cultural, that are missing from the dominant biophysical sciences model of current physical

education curriculum.

These publications have also tacitly recognised the importance of various educational and

pedagogical discourses of different ‘ways of knowing’ and ‘authentic learning’. However, we wish to go

one step further and highlight that to date there is a limited scholarly insight within the physical education

and movement discourses about what we will refer to as:

• The spatialization of the moving body in time • The geographies of physical activity

That is, the distinctive contribution we seek to forge in MEC relates to the ‘yet-to-be-probed’ notions of how

movement and physical activity, and meaning-making and learning, must also account for the perceptual and

intentional affordances, enablement’s and constraints of the various environments that spatially and

geographically influence the human and social experience of movement.3 As such, our notions of the

3

spatialised body and geography of movement for physical education provides an opportunity for

researchers/scholars to consider both the independent and inter-dependent characteristics of movement,

environment and community when explaining physical education, health education or outdoor and

environmental studies in teacher education or continuing professional development.

We will attempt to explicate such concepts by drawing on the available literature of a

phenomenology of movement primarily through the discourses of physical education pedagogy.

Towards a concept of the spatialisation of the body in movement over time and its geographies of physical activity

The literature in the phenomenology of movement highlights a qualification and rejection of a series

of dualisms in the physical education literature. Clearly, physical education is one of those curriculum fields

where the human ‘body’ is central to the primacy of practice and, by necessity, theorization about it.

However, Whitehead (1990) has cautioned that physical education teachers have a philosophical inability to

articulate the subject’s importance and place in the curriculum;

What they are really so concerned to cite are incapable of articulating, namely the achievement of successful liaison with the world via their embodied dimension; or to be exact, between their motile embodiment and the concrete features of the world (p. 6)

Despite this ongoing philosophical theorising of the body and the more pragmatic pedagogic

encounters in physical education appear to slip back into recreating the mind-body and I-world separations

despite the best efforts of many writers cited above (Connolly, 1995). Some scholars such as Smith (1997)

attempt to address these constant limitations. Drawing on van Manen’s (1986) ‘pedagogical thoughtfulness

and tact’, Smith presents the notion of ‘educating physically’, which refers to the teaching of games, sport

and movements in physical education that is embodied and respects the movement experiences of the child.

Those with an interest in the phenomenology of movement will need to remain vigilant to this

slippage because of the ongoing risk of placing the moving body and movement experiences, and their

study, on the periphery of a reoriented physical education discourse. The ongoing challenge we discern is

that a ‘social ecology of movement’ and its pedagogies beckons. To do this, we must be very attentive to

the notions of the spatialisation of the body and geographies of physical activity.

There are numerous theoretical sources to develop the spatialisation and geographies of movement

(for example Maitland, 1995; Noe, 2004; Weiss & Haber, 1999) and physical activity that lie outside the

nascent but revitalized notion in physical education of a phenomenology of movement (see footnote 1).

And, although, the remit of this paper is to focus only on the discourse of physical education, brief mention

must be made in conclusion of two important notions that highlight the spatialisation of the body in

movement in time. Those notions are ‘body schema’ and ‘intentionality’ and, here, we are indebted to

Merleau-Ponty’s (1962) phenomenology of perception.

The notions of ‘body schema’ and ‘intentionality’ (and consequently ‘flesh’), effectively point to the

inseparability and connectedness of the body, in movement, in space and time, with the numerous

environments in which movement occurs, is enabled and constrained (built, structured, urban, open, natural,

treed, footpathed, river, wilderness – for example, we move in particular ways in water, in a pool, on a river,

through a wave and so on). For flesh is more than just the sensorimotor surface of the body. It pertains not

only to a depth, whereby ongoing transactions/interactions with the environment occurs simultaneously,

continuously and in reciprocity (e.g. as in visceral exchanges such as breathing), but as an element of Being.

For children their relationship to movement/sport/physical activity, their embodied connection or ‘flesh in

the world’ is primordial and occurs prior to any self-identification (Smith, 2007). Critically, this

‘inseparable’ connection of the moving body and its environments, effectively deconstructs the basic logics

that persist in western thought about the separations of mind and body, and I and world. Merleau-Ponty’s

‘flesh’ metaphorically elaborates the ‘porous like’ transactional relationship between bodies, environments

and natures. They are mutually constitutive in relation to the meaning-making that occurs for the individual

body in sensing and ‘learning’ of the opportunities, affordances and constraints of the environment but also

there are effects on that environment/nature as a recursive consequence of that movement experience.

Smith’s (2007) account of the ‘rush’ of movement is a very useful description of an environmental

affordance and how the flesh acts as a mediator of that rush;

The child is situated gesturally amidst the flesh of the world through movements that reciprocate the appeals of the landscapes, the seascapes, the airscapes and firescapes. The child’s movements flesh out the mimetic impulse to become the Other. In fact, the power of this impulse is the depth of the flesh that is discerned in the motions of child-like connection to the world (p. 59)

It is in environments of landscape, airscape and seascape where ‘lived’ movement/sporting/physical

activity experiences occur in childhood, often through ‘rushes’ of habituated movement such as swimming,

running, walking and dancing. Beyond reducing children’s movement experiences to our own (Smith,

1992), parents/educators/coaches rarely cultivate or understand the importance and meaning-making of such

landscapes, airscapes, seascapes and connection to ‘rushes’ of movement.

Undoubtedly, there is a risk here of simplifying the important concepts of ‘body schema’ and

‘intentionality.’ But that risk is worth taking so the reader can imagine the directions we are taking in our

theorizations of the spatialisation of the body and geographies of physical activity within the broader

theoretical driver of social ecology and pedagogical platform of experiential education in an education

of/for/with movement/physical activity.

‘Body schema’ is an indicator of the primordiality and, often, primacy of certain bodily dispositions

and capacities, characteristics and qualities that ‘permit’ the pre-conscious, perceptual, intuitive, sensory and

environments, spaces and places, either momentarily or for extended durations. For example, we move

(walk) up a long, steep hill in windy weather in a particular way that differs to moving on sand at the beach.

Or, we turn our head when we hear a noise. Or we gesture with our eyes and hands to a colleague when

verbal communication is insufficient. Or children play in secret spots in particular personal, social and

ecological ways that we have forgotten about. The concept of body schema should not be confused with a

term very popular in physical education and health discourses of ‘body image,’ noting the serious debate in

other literatures about the inappropriateness of the misleading confusion surrounding their interchangeable

use, even in philosophy and cognitive science (Carman, 2008; Gallagher, 2005). Body image relates more

to the idea of the attitudes and beliefs we hold about our own bodies, and those of others. Image connotes a

‘set picture’ of the appearance of the body objectified. And, as such, body image and related concerns about

self-esteem have preoccupied many physical and health educators, amongst numerous others, in regard to,

for example, the culture of thinness/fatness, body types and measures and eating disorders, and so on. Body

schema, therefore, is a conception of the dynamic orientation of the body to and in response to the

experienced lifeworld, or ‘lived experience’ while body image is a more reified objectification of the self

and socially conceived body in that socially constructed lifeworld. Both point to vary different orientations

to the ‘environment’ which, in many instances, overlap. For example, we do walk and dress in particular

ways on the beach according to the combination of the affordances/restraints of the sand/water/waves and a

sense of ‘display,’ appearance and performance. We feel the heat of the sand on our feet; many feel the gaze

of the audience. Of course, there are major implications of the differences and overlap between body

schema and body image for movement experience education, meaning-making that, undoubtedly, differ

from conventional views of physical/health and outdoor/wellbeing educations.

(Body) intentionality, therefore, is closely linked to the notion of body schema in that it highlights

the dynamic nature of the spatiality of the body in movement and, more generally, underpins the notion of

the geographies of physical activity as each pertains to an alternative conceptions and constructions of

physical education and embodied/experiential pedagogies. Simply, intentionality highlights the

‘directedness’ of the orientation to move in a particular way in a particular setting in particular conditions.

Intentionality is ‘automatic’ or ‘pre’ conscious but can be ‘learned’ over time. For example, we ‘learn’ how

to walk and choose a route up that steep hill on a windy day that might differ from the route we select on a

calm or wet day. We intuitively know how, when and where to dive through, or over a wave and, in doing

so, reorient that dive according to a sense of its size and power. There are some parallels here with the idea

and practice of game sense, now frequently taught in physical education classes and in pre-service teacher

education. But, again we refer the reader to footnote 2, and how the physical education teacher operates

within the range of pedagogies listed there that are dominant or marginalized.

So, despite the limitations here, the notions of flesh, of schema and intentionality are indicators of

how a phenomenology of movement addresses the a) spatialisation of the body in movement in different

environments and b) geographies of physical activity. They are partially implied, even sometimes directly

included in the physical education discourse. Our reading of the physical education discourse suggests that,

by and large, the mention of spatiality and geography of activity is located in the instrumental and

performative logics/outcomes of that discourse. The phenomenological discourse, and MEC’s distinctive

contribution, aims to ‘open up’ that discourse via a considered view of what is currently excluded and might

need to be re-included, such as the notions of embodied knowing, somatic understanding, ecological

subjectivity, intercorporeality (between bodies), kinaesthetics, somaesthetics and so on.

We reiterate that notions like the spatialisation of the body in movement and geographies of physical

activity are important ingredients of the theory of social ecology and pedagogy of experiential education.

They are important because of the way in which the embodied making of meaning through movement and

physical activity in various environments over times are, indeed, major sources of an expanded notion of

learning which, if so, is part of the legitimation process that physical education has struggled with, for far

too long. Often seen as mere ‘doing’ curriculum areas like physical education and outdoor education that

privilege the moving, active, experiencing body do offer a rich and extensive qualities and characteristics of

meaning and learning that are unable to be offered in the classroom.

The challenge for us and physical education is for physical educators to recognize how the nascent

but revitalizing phenomenology and social ecology of physical education can enhance its endeavours

conceptually and practically in ways that have not been previously envisaged, or only partially so.

Summary

It is clear that those writing in the genre of a phenomenology of movement are committed to how

the moving body (in time/space) is a source, or origin, and reflection of meaning and meaning-making. The

phenomenological discourse shifts our ecological attention to some of the more intrinsic qualities and

characteristics of the body(ies) in movement in time and space. In so doing, at least, a renewed sense of

agency is therefore implied I regard to developing the theory and practice of physical education. We feel

this positive sense of agency fostered by the meaning-making dimensions of movement is probably a

‘primitive’ or ‘primacy’ of practice and, therefore, prerequisite to more earnest accounts of conception and

learning undertaken rationally by the various critical, post-structural and applied-science discourses.

To be sure, movement, both situationally and contextually, is inextricably linked to the affordances,

enablements and constraints of the various environments that spatially and geographically influence the

human and social experience of movement. In addition to the spatialities of movement, their geographies

also shape how communities act as the ‘driver’ of social and environmental capital and their sustainability.

The phenomenological, or ‘micro’ study of, for example, the body schema and image in movement provides

a ‘critical’ window through which the social, cultural and ecological ‘world’ might also be examined.

This social ecology of movement therefore addresses at different levels the relationships between

human, social, built and natural environments – a prerequisite for the promotion of health, wellbeing and

place, will positively deconstruct the disconnects of mind-body, organism-environment, I-we-world and,

inevitably, ontology-epistemology-methodology that, currently, continue to fuel the theory-practice gap in

physical education.

References

Archer, M. S. (2000). Being Human - The problem of agency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Arnold, P. J. (1979). Meaning in movement, sport and physical education. London: Heinemann.

Bain, L. L. (1995). Mindfulness and subjective knowledge Quest, 47, 238-253.

Best, D. (1978). Philosophy and Human Movement. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Brown, T. D. (2008). Movement and meaning-making in physical education. ACHPER Healthy Lifestyles

Journal, 55(2/3), 5-10.

Carlson, T. B. (1995). We hate gym: student alienation from physical education. Journal of Teaching in

Physical Education, 14, 467-477.

Carman, T. (2008). Merleau-Ponty. London: Routledge.

Connolly, M. (1995). Phenomenology, physical education, and special populations. Human Studies, 18,

25-40.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1977). Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Egan, K. (1997). The educated mind. New York: Teachers College Press.

Fife, G. (2008). The beautiful machine - a life in cycling, from tour de france to cinder hill Edinburgh:

Mainstream Publishers.

Gallagher, S. (2005). How the body shapes the mind. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: the theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Gerber, E. W., & Morgan, W. J. (1979). Sport and the body: a philosophical symposium. Philadelphia,

PA: Lea & Febiger.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge: Polity

Press.

Kentel, J. A., & Dobson, T. M. (2007). Beyond myopic visions of education: revisiting movement literacy.

Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 12(2), 145-162.

Kirk, D. (2003). Sport, physical education and schools. In B. Houlihan (Ed.), Sport and Society - A student

introduction. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Kleinman, S. (1979). The significance of human movement: a phenomenological approach. In E. W.

Gerber & W. J. Morgan (Eds.), Sport and the Body: A Philosophical Symposium (pp. 177-180).

Kretchmar, R. S. (2000). Movement subcultures: sites for meaning JOPERD, 71(5), 19-25.

Kretchmar, R. S. (2005). Practical Philosophy of Sport and Physical Activity (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL:

Human Kinetics.

Kretchmar, R. S. (2007). What to do with meaning? A research conundrum for the 21st century. Quest, 59,

373-383.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the Flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to

western thought. New York: Basic Books.

Lambert, C. (1998). Mind over water: lessons on life from the art of rowing. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Maitland, J. (1995). Spacious body: explorations in somatic ontology. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Metheny, E. (1965). Connotations of movement in sport and dance. Dubuque, IA.: W.C. Brown

Publishers.

Metheny, E. (1968). Movement and meaning. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Noe, A. (2004). Action in perception. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

O'Loughlin, M. (1997). Corporeal subjectivities: Merleau-Ponty, education and the postmodern subject.

Educational Philosophy and Theory, 20-31.

Quennerstedt, M. (2008). Studying the institutional dimension of meaning making: a way to analyze subject

content in physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 27, 434-444.

Roberts, J. (2008). From experience to neo-experiential education: variations on a theme. Journal of

Experiential Education, 31(1), 19-35.

Ryan, M., & Rossi, T. (2008). The Transdisciplinary Potential of Multiliteracies: Bodily Performance and

Meaning-Making in Health and Physical Education. In A. Healey (Ed.), Multiliteracies and

Diversity in Education - New Pedagogies for Expanding Landscapes. Melbourne, VIC: Oxford

University Press.

Sallis, J. F., Cervero, R. B., Ascher, W., Henderson, K. A., Kraft, M. K., & Kerr, J. (2006). An ecological

approach to creating active living communities. Annual Reviews of Public Health, 27, 297-322.

Shusterman, R. (1997). Practicing philosophy: pragmatism and the philosophical life. New York:

Routledge.

Shusterman, R. (2008). Body Consciousness - A philosophy of midfulness and somaethetics. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Smith, S. J. (1992). Studying the lifeworld of physical education: a phenomenological orientation. In A.

C. Sparkes (Ed.), Research in physical education and sport - exploring alternative visions (pp.

Smith, S. J. (1997). The phenomenology of educating physically. In D. Vandenburg (Ed.),

Phenomenology and educational discourse. Durban: Heinemann.

Smith, S. J. (2007). The first rush of movement: a phenomenological preface to movement education.

Phenomenology and Practice, 1, 47-75.

Thoreau, H. D. (1966/1982). Some thoughts on walking. In H. Wind (Ed.), The realm of sport (pp.

674-677). New York: Simon and Schuster.

Tinning, R., & Fitzclarence, L. (1992). Postmodern youth culture and the crisis in Australian secondary

physical education. Quest, 44, 287-303.

Trost, S. G. (2004). School Physical Education in the Post-Report Era: An Analysis From Public Health.

Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 23(4), 316-335.

Van den Berg, J. H. (1952). The human body and the significance of human movement - A

Phenomenological Study. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 13, 159-183.

van Manen, M. (1986). The tone of teaching. Richmond Hill, Ontario: Scholastic Publications.

van Manen, M. (1997). Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy

London, Ontario: Althouse Press.

Weiss, G., & Haber, H. (1999). Perspectives on embodiment: the intersections of nature and culture. New

York: Routledge.

Whitehead, M. E. (1990). Meaningful existence, embodiment, and physical education. Journal of

Philosophy of Education, 24(1), 3-13.

Whitehead, M. E. (2001). The concept of physical literacy. Paper presented at the International

Association of Physical Education and Sport for Girls and Women (IAPESGW) Congress,

Paper 2: Environment, place and social ecology in educational

practice

Brian Wattchow, Geraldine Burke and Amy Cutter-Mackenzie

Introduction

‘Environment,’ like ‘nature,’ is an ambiguous term because of the many environments that do exist

and the different ways in which they are perceived and socially constructed over time and through space.

Educators must be careful about the way meaning is ascribed to ‘environment’ and ‘nature’ if sustainability

is to remain a plausible proposition. For example, the same school ‘environment’ may simultaneously be

perceived by teachers and students as a sporting arena for testing human physical performance, a landscape

of shapes, light and colours for the art class, or as a ecology in need of examination and management in a

science subject. These examples mark only the beginning of a very long list of the multiple, complex and

even contradictory ways that various pedagogic environments may be viewed and therefore experienced.

Environments can be personal, social, historical, built, natural, tame or wild. The integrity of each

environment warrants study and requires a particular pedagogic response. Educators should be mindful of

the various ways in which teachers and students shape and are shaped by these learning environments

physically, emotionally and intellectually stands to make a significant contribution to the creation of active

communities and the promotion of health, wellbeing and sustainability.

Hence, a 'social ecology' of the complex term ‘environment’ is urgently required to enhance our

pedagogical and research efforts in outdoor, environmental, movement, physical and health educations.

What is needed is a conceptual shift in our thinking and bodily practices towards an ‘ecocentric’ or place

responsive posture; a philosophical frame quite different from the anthropocentrism, or human centredness

of most educational discourses.

In practical terms, a social ecology of the environment, in relation to the study of movement and

community experiences, entails in pedagogical practices a range of human-environment interactions, be it

open-space play, active art projects, walking to school, or outdoor education expeditions. A constant in

these examples is the taking of education away from the environmental constraints of the ‘indoors,’ and its

privileging of mind/learning/knowing, to the environmental enablements of the ‘outdoors’ and body/mind

doing, meaning-making and becoming. A social ecology of these human-environment interactions and

relations address various ‘other’ and ‘wild’ forms of expression and performance - be it strenuous activity in

space, graceful movement in place, or kinaesthetic appreciation over time in different places.

This paper addresses some of the more ‘ecocentric’ and wild, less tamed concerns outlined above

and leaves others to the ‘Movement’ and ‘Community’ papers. Simply, our aim is to outline the major

distinguishing characteristics and dimensions of ‘environment’ so that inquiry of an ecological type can

active and sustainable communities. To ground this in our research efforts, we focus on ‘place’ study - an

important derivation of the nature/environment concepts. We offer vignettes about ‘the experience of river

places in outdoor education, children’s gardens and artistic representations of pedagogies of place. But first,

what do we mean by the term ‘place’?

Place and space

Place, as a concept, has been extensively discussed in the work of humanist geographers such as

Tuan (1975, 1977), Relph (1976, 1985) and Seamon (1979, 1992, 2004). Yet use of word ‘place’, and the

phrase ‘a sense of place,’ has become so commonplace that they stand to have their meaning diminished. At

the heart of this issue is confusion between the concepts of space and place.

The relationship between space and place remains one of the most difficult challenges facing

researchers and practitioners alike. On the one hand there are those who consider that place is ‘made’

through the accumulation of human experience (see for example, Meinig, 1979; Relph, 1976). On the other

there are those who propose that place has its own inherent spirit and meaning waiting to be discovered (see

for example, Park, 1995; Tacey, 1995). Differences between place as culturally constructed space or place

as a site of intrinsic meaning are important to understand because they potentially bear on the ways in which

teachers and participants locate themselves within, move through, and identify themselves with outdoor

environments.

Casey (1996, p. 14) argues that it was the abstract physics of Newton and the critical philosophy of

Kant that has resulted in places becoming “the mere apportionings of space, its compartmentalisations.” In

his argument for a return to place, Casey (1996, p. 20) asks us to avoid the “the high road of modernism …

to reoccupy the lowland of place.” Place can then be considered both pre-modern and post modern; “it

serves to connect these two far sides of modernity” (Casey, 1996, p. 20). Space is abstracted in the mind.

Place is inevitably lived in, first and foremost, through the body.

The New Zealand ecological historian Geoff Park (1995, p. 331) suggests that “any stretch of

country, no matter how pervasive agriculture’s marks, has an indwelling life force, waning or waxing, which

distinguishes if from any other.” Why is it necessary to consider the importance of sense of place and place

attachment in education? Park (1995) answered this question simply and decisively when he wrote, “a sense

of place is a fundamental human need” (p. 320). In his highly influential book Place and Placelessness,

Relph (1976, p. 6) demonstrated how places serve as “sources of security and identity”, but also how the

homogenising influence of modern practices can result in the experience of displacement or rootlessness.

Educating for a responsiveness to place assumes that at least part of education is about preparing people to

“to live and work to sustain the cultural and ecological integrity of the places they inhabit” (Woodhouse &

Place and education

Yet according to David Orr (1992), educators have failed to see much significance in understanding,

or attempting to teach a responsiveness to the particular places where teaching and learning is located. He

explains that “place is nebulous to educators because to a great extent we are deplaced people for whom

immediate places are no longer sources of food, water, livelihood, energy, materials, friends, recreation or

sacred inspiration” (p. 126). The typical curriculum, according to Orr is based upon abstraction, which

disconnects people from “tangible experience, real problems, and the places where we live and work” (p.

126).

Place cannot, like the content of some subjects, be studied at a distance. Rather, place is a lived

phenomenon. Students and teachers both make and are made by the place they live and work within. This

reciprocal relationship – place as lived experience – makes it a compelling and accessible theme for all kinds

of experiential educators. Geography, history, art, environmental science, outdoor education and even health

and physical education can all benefit from a focus on place. But it does require, on the part of educators and

learners, a return to the immediacy of the local – that combination of topography, climate and ecology along

with human activities and their signs, symbols and rituals that gives a place its unique distinctiveness.

Hence, a social ecology of environment as place.

The following vignettes represent some of our attempts to return, with our students and program

participants, to the immediacy of place, to encounter them with mind and body, and to refine pedagogies that

respond to them. Each story gestures towards the potential for educators and learners to make a significant

contribution to the social ecology of their community through carefully developed experiential pedagogies.

A number of pedagogical implications are drawn from each vignette for the reader to consider.

Vignette 1: Creating Connections to place (Geraldine Burke)

A sense of place is a virtual immersion that depends on lived experience and a topographical intimacy that is rare today both in ordinary life and in traditional educational fields…. it demands extensive visual and historical research, a great deal of walking “in the field”, contact with oral tradition, and an intensive knowledge of both local multiculturalism and the broader context of multicentredness.

Lucy Lippard (1997, p. 33)

the best fun, must be somethin! Must be healthy! Sunny days, sunny people, sunny paintin, sunny colours – many sandshoes Mother Earth. 4

Tony Nelson artist statement, Creative Junction Project (2005)

The joint Shire of Yarra Ranges–Vic Health, Creative Junction project sought to rethink the public

space as both an internal and external site for artistic expression (Vic-Health, Mental health and Wellbeing -

Art and Community grant Reference No. 2003-0557). Its priorities were to promote a sense of social

connectedness, economic participation, diversity and freedom from discrimination. It aimed to connect art

and environment to personal, meaningful experience and to develop and express a sense of place through art.

Accordingly the Creative Junction project was inspired by the community’s stories, artwork and living

culture; as well as their connection to the land and to each other.

As Artistic Coordinator, working within a project team, I developed a program of site based events

designed to engage community in situated, embodied art activities exploring local culture with nature, in

nature and about nature. This approach reflected UNESCO’s art education directive that ‘visual arts learning

can commence from the local culture, and progressively introduce learners to other world cultures.’

(UNESCO 2004, p. 43).

The art program aimed to challenge everyday notions of the landscape genre, such that we were

positioned inside its experience rather than onlookers to its view. Inspired by the poetry of Judith Wright we

wanted to express rather than describe place; to adopt a disposition that “…lives through landscape and

event” (Wright, 1961, p. 96). We wanted to expand on western notions of place, to become aware of

Indigenous views of country (Rose, 1996), and to learn to play and create with found materials as a means to

undertake material thinking (Carter, 2004) as arts based research.

Following a literature review, extensive consultation with the community and project team, we

commissioned a series of ‘connector’ artworks. Expressing local knowledge and connecting the community

to place and each other, were viewed as central to the formation of these works. They consisted of:

- A series of community workshops, focusing on nature and art to express ways of knowing;

- Permanent environmental artworks;

- Ephemeral artworks that utilised natural objects from the area as agents for

- Creative connection to local culture and sense of place;

- On going photographic and narrative documentation of the artistic process;

- Creative Junction festival days,

4

- Postcards and interpretive signage that reflected the project aims and allowed for ongoing reference to

the events that surrounded the project.

Fundamental to our immersive art program was a consistent emphasis on walking and talking the land

whereby collecting natural materials and making artworks were seen as combined experiences. Our program

of events invited participants back into nature in ways that encouraged them to look, smell, find, examine

and collect objects from place for use in artistic processes and outcomes, believing, as per Emily Brady

(2003, p. 127) the environmental philosopher, that our sense of place can be influenced by an

“...(A)ppreciation of aesthetic qualities through sensory engagement which is ‘directed to a great degree by

qualities perceived…”. In the process we reframed and revisited place so as to tease out relational aspects

between viewpoints, seeking Indigenous, botanical, historical, artistic, playful and logging perspectives. We

hoped that this capturing of layered experiences would enable us to see, as per (Rogoff, 1995), how we were

connected and involved in each others definition. The place responsive art that emerged from the project

reflected a view of environmental art whereby the individual’s connection to the environment is primary

(Wallis and Kastner, 1998, p. 11) a view that also seeks to relocate the artist and viewer from observer of

nature to participant in it.

To achieve optimum creative engagement we used a developing framework for immersive art

pedagogy (Burke, 2004; 2005; 2007) which sought to link a system’s view of creativity (Csikszentmihalyi,

1996) to a radical/local view of pedagogy (Hedegard and Chaiklin, 2005). This approach promoted local

knowledge/s alongside the discipline knowledge of art within socio-cultural and critical ways of knowing.

The art/research/teaching that became the living inquiry within the Creative Junction project is also

understood through a/r/tography (Irwin, 2004) an arts based approach to research which pays heed to the

in-between (Grosz: 2001) where meanings reside in the simultaneous use of language, images, materials,

situations, space and time (Irwin & Springgay, 2008, p. xix). In so doing we troubled our awareness and

knowing, so as to embody theory-as-practice-as-process-as-complication. (Irwin & Springgay, 2008, p. xi).

From this A/r/tographic perspective we no longer understood place as being geographically bound (Doherty,

2004, p. 8). In addition, as per Kwon’s (2002) notion, we came to envision the concept of ‘site’ as a

complex figure in the unstable relationship between location and identity (Irwin and Spinggay: 2008, p.

xxvi).

Meta knowledge of the creative process helped us further develop a creative connection to place and

each other. Csikszentmihalyi’s systems model of creativity (1996) enabled us to consider the

cultural/community denomination of creativity and to go beyond an understanding of individual creativity to

one that valued the interrelated sites of creativity; namely the domain, the field and the individual.

Csikszentmihalyi’s attention to the ‘where’ of creativity (1996, p. 27) suggests that creativity does not

happen inside people’s heads, but in the interactions between a person’s thoughts and a socio cultural

context.

In the Creative Junction project the domain was understood through the site of Yarra Junction. The

continues to contain the remnants, past or present, that exist in this place reflecting a diverse continuum of

knowing as explored through stories and artefacts.

The field was perceived as the funding bodies, project management team, selected project artists and

participating teachers from local schools and kindergarten who constituted the primary gatekeepers to the

symbolic knowing of place. This field aimed to further recognise, preserve and remember the culture of this

place and culture generally, as actualised through our visual journaling process, project marketing, publicity

material, scholarly articles, editorials, postcards and brochures that celebrated our project

Individuals participated in art workshops and the making of ephemeral culptures which exposed

them to concepts in the domain and which were documented for possible inclusion in postcards and project

documentation. Further these individuals were mentored through the process by field members, being the

artists, teachers and project team members. As well, community members who did not participate directly in

the project but who received project postcards were further introduced to the domain and the artwork of their

fellow community members through the postcards.

The Creative Junction project continues to inspire my own environmental art investigations within

my PhD and lives on as an introductory experience for pre-service teachers at Monash University involved in

art/place and environment activities. The stories and informing theories behind the Creative Junction project

also have implications for educators and students within a broader context and can be conceptualised through

the following pedagogical applications.

1. Teachers and learners can become active agents in shaping the knowledge, art and narratives of a

given place. Both teachers and learners can harness locally found materials, corresponding art

methods, and relational narratives and associations of place rather than passively delivering ready

made content from other sources. In so doing they are performing a type of Bricolage (Denzin and

Lincoln, 2008) and can in the process become aware of pedagogical approaches that acknowledge

complex connections between identity/ies, expression/s, place/s and power.

2. The outside environment generally lends itself to an experiential use of materials, movement and

situation and can be harnessed by teachers and students as a means to link into the local. In this way

teachers and students can enact a double move (Hedegard and Chaklin, 2005) such that students can

connect their living enquiry (Irwin and De Cosson, 2004) of place and environment with the

discipline knowledge of art, and in turn, teachers can connect their art knowledge to the local findings

of their students.

3. Our daily life has become more inside focused. A cultural transition from the classroom to the

outside learning zone could open up opportunities for art education by utilizing

walking/talking/(environmentally sound)collecting/and making as pedagogical devices that allow us

to create from within the experience of environment and place rather than as mere onlookers to its

4. Creativity can be conceptualised as a personal AND societal pursuit that opens up community

connections between the individual, the field and the domain.

5. A place can be conceptualised as a creative site that can be explored and revealed by the following

phases identified through immersive art pedagogy. (Burke: PhD in progress; 2008).These may entail,

Walking place - as an aesthetic and reflective way of connecting to place;

Wondering place - through tactile engagement with natural materials;

Listening to place and each other - through art and narrative;

Exploring place - through nature;

Expressing place - through art and nature;

Deep learning - in, through and about art and nature;

Wellbeing through aesthetic engagement with place - through art and nature;

Valuing of diversity - through art and nature

Imaginative possibility and enjoyment - through art and nature

Critical awareness of place – through art and narrative

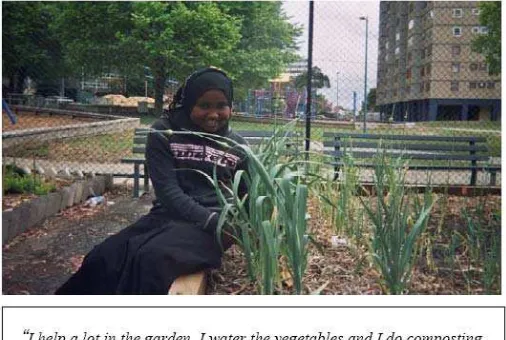

Vignette 2: School Garden Experiences – Fostering Place (Amy Cutter-Mackenzie)

For the past decade gardening programs have become increasingly popular in Australian schools as

teachers seek pedagogical approaches to engage children in experiential learning and work towards tackling

societal concerns such as childhood obesity and environmental sustainability (Miller, 2007). The desire to

enable children to experience ‘slow’, less technologically focused experiences (Payne, 2003; Payne &

Wattchow, 2008) and to address concerns that children are growing up with what Louv (2005) describes as

“Nature Deficit Disorder” are additional drivers that have led teachers and communities to embrace school

gardening programs. Mayer-Smith et al. (2007, p. 85) found that “children’s relationship with the

environment changed and became more personal” over the course of an Intergenerational Landed Learning

Project. They noted that “the majority of children shifted from seeing the environment as an object or a

place, to a view characterized by the interconnectedness of humans and environment” (p.83). With that in

mind, Wake (2008, p. 432) argues that further research is needed with respect to “what children are looking

for in a nature connection, if indeed they are looking” in the context of children’s gardens programs. She

maintains that there is a tendency for adults to romanticize nature and utilize this to legitimize children’s

interactions with nature through garden programs.

While there is a growing body of research focused on the benefits of school gardening programs,

there is a dearth of research about children’s school garden experiences and how these experiences influence

their notions of place. In this vignette I report on children’s gardening experiences. The focus of the

vignette is the Multicultural School Gardens program that was implemented in disadvantaged schools in the

greater metropolitan of Melbourne. Food gardening and cultural diversity are the focus of the program. The

participating schools have high proportions of migrant and refugee families. Alongside the implementation

and teachers) documented their experiences (A. Cutter-Mackenzie, 2007; A. Cutter-Mackenzie, 2008;

2005). Five schools (4 primary schools and 1 secondary school) have participated in the research process

over the two year duration of the project. Students were invited to capture their experiences by keeping a

journal, taking photographs and interviewing students, teachers, parents and community members about their

Multicultural School Gardens experiences. All students and teachers also participated in a focus group

interview to discuss their experiences. What follows is a brief account of one primary school’s experience

identifying the key themes generated through their research.

City Heights Primary School comprises a student body of approximately 90 children who reside in

an estate in the same location as the school (on site). The school has a strong environmental education focus

and established links with the surrounding community. The school’s motivation for joining the program was

driven by a desire to facilitate ‘real life learning’ for children who live in high density apartment

accommodation and have very limited opportunities to garden and engage in outdoor learning. The

environmental education coordinator, a year six teacher, emphasized that experiential learning is a key

pedagogical driver for his school which allowed for the inclusion of the multicultural school gardens

program:

We have changed most of our curriculum to incorporate a hands-on and experiential learning approach. For example, the younger kids do a lot of developmental play rather than formal lessons so the garden program fits into our curriculum quite well.

City Heights Primary School supported their students in designing and constructing their gardens.

Recently Wake (2008) noted that children do not tend to have these opportunities in children’s garden

programs. The process by which this was done for the multicultural school gardens project drew upon the

children’s cultural heritage by involving their parents and grandparents as advisors. Teachers and

community groups were also made available as advisers which together with the children’s parents and

grandparents prompted intergenerational and cultural led learning.

The students’ research indicated that the garden project has had a positive impact on nutritional

knowledge and healthy eating behaviours. One student commented “I learnt that you get stronger and

healthier. I used to eat chips but now when I get hungry I eat a piece of fruit”. Furthermore, the

environmental education coordinator reported a ‘flow-on effect’ as the healthy eating message reached

families, stating that the school had “seen changes in behaviour, especially the kids who were coming in the

morning with a can of Coke for breakfast”. While Ozer (2007) maintains that research must move beyond

reporting the nutritional benefits of children’s garden programs, this finding must not be downplayed given

the harsh reality that an increasingly number of Australian families are adopting the values and culture of a

fast-food society where children are consuming high-calorie, low-nutrition food, doing little exercise and

have limited experiences in outdoor environments. According to the school’s environmental education