INDONESIA’S FORESTRY LONG TERM

DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2006-20025

THE MINISTRY OF FORESTRY OF INDONESIA

Published by :

Centre for Forestry Planning and Statistics,

Forestry Planning Agency – The Ministry of Forestry of Indonesia Manggala Wanabakti Building, Block VII, 5 Floor;

Jl. Gatot Subroto Jakarta, 10270 Phone/Fax: +62 21 5720216

© The Ministry of Forestry of Indonesia 2006

ISBN:

Edited by:

Basoeki Karyaatmadja; Muhammad Koeswanda; Chaerudin Mangkudisastra; Belinda Arunarwati;

Efsa Caesariantika; Arie Sylvia Febriyanti

Printed by :

INDONESIAN NATIONAL FORESTRY STATEMENT

1

Indonesian forest resources, which function as one of the components of

the life support system, constitute a trust from God for the people of

Indonesia to be wisely managed so that they can provide optimal and

sustainable benefits. Up to now, Indonesian forest resources have provided

benefits as one of the main financing modes of national economic

development, in the form of economic growth, labour absorption and

regional development.

The commitment to manage forest resources is already in effect and aims

toward forest preservation and sustainable development. In fact at this

time, however, there are still weaknesses in management that are causing

a decline in quantity and quality of forest resources, which at last are

causing the appearance of environmental damages, economic losses, and

social impacts at a very worrying level.

It is recognized that there is a diversity of desires, goals, and interests to

various parties, including local, national and even global communities, for

the benefits of forest resources. The solution for overcoming the issues

above will be based on agreement by concerned forest sector stakeholders,

based on equity and justice, as well as highlighting proposed management

principles and existing values.

Starting now, the Indonesian nation had determined to make every effort

to manage forest sustainability, prioritizing in the short run the protection

and rehabilitation of forest resources for the greatest possible prosperity

and justice for people.

1Based on multi-stakeholder consultations in 6 main regions (Sumatra, Java-Bali, Nusa Tenggara, Borneo, Celebes, Maluku,,

MINISTER OF FORESTRY OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA

REGULATION OF THE MINISTER OF FORESTRY Number : P.27/Menhut-II/2006

Concerning

INDONESIA’S FORESTRY LONG TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2006-20025

MINISTER OF FORESTRY,

Consider : a. that, the act Number 41 of 1999 concerning Forestry, in particular article 20, and the act Number 25 of 2004 concerning National Development Planning System in which mandate to arrange Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan 2006-2025;

b. that, to follow up the above mention, The Ministry of Forestry need to arrange Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan 2006-2025;

c. that, due to the circumstance above, Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan 2006-2025 is necessary to decide into a Regulation of the Minister of Forestry.

Refer to : 1. Act Number 5 of 1990 concerning Conservation of Natural Resources and its Ecosystems;

2. Act Number 24 of 1992 concerning Spatial Planning;

3. Act Number 23 of 1997 concerning Environmental Management; 4. Act Number 41 of 1999 concerning Forestry;

5. Act Number 25 of 2004 concerning National Development Planning System;

6. Act Number 32 of 2004 concerning Local Government;

7. Government Regulation Number 25 of 2000 concerning Authority of Government and Authority of Provinces as Autonomous Territories;

8. Government Regulation Number 34 of 2000 concerning Forest Administration, Forest Management Planning, Forest Utilization, and Forest Land-Use for Non-Forestry Purposes;

9. Government Regulation Number 44 of 2004 concerning Forestry Planning;

10. Presidential Decision Number 187/M of 2004 concerning Development of the Indonesian United Cabinet;

11. Presidential Regulation Number 7/M of 2005 concerning National Mid-term Development Plan 2004-2009;

12. Presidential Instruction Number 7 of 1999 concerning Performance Accountability of Government Institutions;

13. Minister of Forestry Decision Number SK456/ Menhut-VII/2004 concerning Five Priority Policies on Forestry in the National Development Program of the Indonesia United Cabinet;

14.

Decision of Head of National Administration Institute, Number 239/IX/8/2003 concerning Revised of the Guideline for Arranging Report of Performance Accountability of Government Institutions.

DECIDES

to stipulate :

FIRST : Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan 2006-2025, as annexed to this regulation,

SECOND : Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan 2006-2025 is arranged as a direction and reference for :

a. Development of Strategic Plans of The Ministry of Forestry ;

c. Development of Sub-National Forestry Development Plans;

d. Coordination of inter sectors long term planning;

e. Control of development activities under the Ministry of Forestry.

THIRD

: To instruct Echelon I in the Ministry of Forestry to:

a. Elaborate Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan 2006-2025 toward strategic forestry planning in shorten term;

b. Develop Report on Performance Accountability of Government Institution for their respective units based on Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan 2006-2025.

FOURTH : This regulation shall come into effect at the date of its stipulation.

Issued in : JAKARTA On : May 17, 2006 Declaring that this copy MINISTER OF FORESTRY

complies with the original,

Director of Legal and

Organisational Affairs, Signed

Signed

SUPARNO, SH H.M.S. KABAN, SE., M.Si.

Personnel No. 080068472

Cc:

1. Executive Official of National Audit Agency 2. Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs 3. Minister of Finance

4. State Minister of National Development Planning/Head of National Development Planning Board

5. All Governors in Indonesia

ANNEX :

Regulation of Minister of Forestry Number : P.27/menhut-II/2006 Date : May 17, 2006

CONCERNING

INDONESIA’S FORESTRY LONG TERM

PREFACE

Sustainable forest resources management as mandated in the Basic Law 1945 Article 33 obligates to the government to have the legally basis, encompassing short term, middle term, and long term planning implication which fully integrated vertically and horizontally. Therefore, simultaneous and iterative process needed within the preparation of those planning toward achieving the benefits, existence, sustainability of the forest resources, and people’s prosperities.

The Governance system development from centralized to decentralized (the autonomy era) and refer to the riel condition of forestry sector prosecutes huge endeavor within transparent manner, to ensure the direction and contribution of forestry sector could cross boundary time and space, and it could be carried out more harmonized, convergent and focus, starting from the management unit up to the central level.

Based on the logical framework and fulfillment of obligation as mentioned above, Ministry of Forestry established Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan 2006 – 2025 which intended to raise the common perception of all parties concerning the forestry sector.

Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan remains highly strategic and important as a forestry development scenario toward national development within the next 20 years, where this document has been prepared within a year since April 2005. Discussion and public consultation have conducted through 2 national workshops by involving various stakeholders including technical expert, to scope several points of multi sectors and related knowledge. Dialogues among those relevant stakeholders yield significant contributions such as alternates scenario, empirical fact and logical concept to prepared Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan.

Based on awareness, that the movement of strategic environmental in the forestry sector is dynamic internally and externally, and related to other sectors even a global influence, therefore Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan viewed as an iterative process within possibilities on review which might timely happened in accordance with National long term interest.

Regardless of the negative occurrence within the arrangement of this Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan, the Ministry of Forestry wishes to express its sincere appreciation and gratitude to the officials and numerous individuals who have contributed and actively involved to the preparation of this document, as a guidance to manage Indonesian forest resources in the future.

The Ministry of Forestry hope, Indonesia’s Forestry Long Term Development Plan 2006 – 2025 could be utilized as a guideline and a reference for further understanding toward strategic forestry planning in shorten term, and concurrently as a source of indicators measurement of Performance Accountability of Government Institution in forestry sector.

MINISTER OF FORESTRY

Signed

LIST OF CONTENT

Page

PREFACE ... i

LIST CONTENT ... ii

LIST OF FIGURE... iv

LIST OF TABLE ... vi

GLOSSARY... vii

BAB I INTRODUCTION ... 1

I.1 FOREWORD ... 1

I.2 DEFINITION ... 2

I.3 PURPOSE AND GOAL ... 2

I.4 LEGAL BASIS ... 2

I.5 ASSUMPTIONS ... 3

I.6 FORESTRY LONG TERM DEVELOPMENT PLANNING FORMULATION PROCESS ... 3 BAB II THE STATE OF FORESTRY UNTIL 2004 ... 5

II.1 FOREST RESOURCES ... 5

II.2 STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS ... 10

II.3 STRATEGIC ISSUES FOR FORESTRY DEVELOPMENT ... 12

II.4 FORESTRY DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL ... 25

BAB III VISION AND MISSION FOR FORESTRY DEVELOPMENT 2006-2025... 30

III.1 VISION ... 30

III.2 MISSION ... 32

BAB IV FORESTRY LONG TERM DEVELOPMENT DIRECTION 2006-2025 ... 33 IV.1 MAIN OBJECTIVE ... 33

IV.2 THE CREATION OF A STRONG INSTITUSIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR FORESTRY DEVELOPMENT ... 35 IV.3 ACHIEVING INCREASED VALUE AND SUSTAINABLE PRODUCTIVITY OF FOREST RESOURCES ... 37

IV.4 FORESTRY PRODUCTS AND SERVICES THAT ARE ENVIRONMENTALLY FRIENDLY AND COMPETITIVE, AND THAT HAVE HIGH ADDED VALUE ... 42

IV.5 CREATING AND ENABLING FORESTRY INVESMENT CLIMATE ... 44

IV.7 IMPROVING SOCIAL WALFARE AND RAISING SOCIETY’S ACTIVE ROLE IN SUPPORTING RESPONSIBLE AND EQUITABLE

FOREST MANAGEMENT ... 46

BAB V THE ROLE OF FORESTRY DEVELOPMENT 49

BAB VI CLOSING ... 53

REFERENCE... 55

LIST OF FIGURE

No Page

Figure 1. Indonesia’s biodiversity ... 5

Figure 2. Development of Indonesia’s protection zones by size (left axis) and number (right axis) over time... 6 Figure 3. Community honey bee production ... 7

Figure 4. Forest product exports (left axis) and contribution to GDP (right axis) up to 2003... 8 Figure 5. Natural forest concessions (HPH) until 2004... 8

Figure 6. Forestry revenues, 1999 to 2004 (trillion Rp) ... 9

Figure 7. Employment in the forestry sector until 2002... 9

Figure 8. Planned versus achieved reforestation (1984-2003) ... 13

Figure 9. Area of the forest area cleared up to 2004 ... 14

Figure 10. Development of HTI plantations up to 2004... 15

Figure 11. Roundwood production from HPH up to 2004 ... 16

Figure 12. Production of non-timber forest products up to 2002 ... 16

Figure 13. Area of forest fires up to 2004 ... 17

Figure 14. Change in forest cover in Sumatra 1988 – 2000 ... 19

Figure 15. Declining tiger population in sumatra ... 20

Figure 16. Conflict between tigers and humans ... 20

Figure 17. Percent forest cover and rural poor ... 21

Figure 18. Employment classification of rural poor and non-poor, 2002 ... 22

Figure 19. Educational level of national civil servant in forestry at central and regional levels ... 22 Figure 20. Educational level of national civil servant and private sector employees, 2002 ... 23 Figure 21. Human resources in forestry research and development (Litbang)... 24

Figure 22. Results of illegal logging cases, 2003 ... 24

Figure 23. Classifications of the forest area ... 25

Figure 24. Education levels of forestry employees ... 26

Figure 27. Plant and wildlife exports, 2000–2004... 28

Figure 28. Visitors to conservation areas ... 29

Figure 29. Target for developing KPH institutions up to 2025 ... 35

Figure 30. Program for developing forestry human resources until 2025 ... 36

Figure 31. Target for measuring the forest area by 2025 (million ha) ... 38

Figure 32. Scenarios of decreasing forest degradation in the forest area 2025 ... 38

Figure 33. Target for watershed revitalization by 2025 ... 39

Figure 34. Development of independent conservation areas by 2025... 40

Figure 35. Target for reducing the number of protected species by 2025 ... 41

Figure 36. Target for inventories of all timber and commercial wildlife species by 2025 ... 42

Figure 37. Roundwood production scenario until 2025 ... 44

LIST OF TABLE

No Page

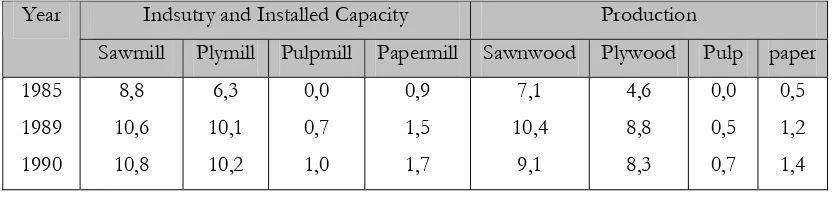

Table 1. Production capacity changes of Indonesia’s forestry industries 1985-2002 (million m3)...

17

Table 2. Global veneer, plywood and pulp production, 2003 ... 18

Table 3. Distribution of critical land in and outside the forest area (million ha) ... 19

Table 4. Population and poverty distribution in Indonesia 2003 ... 21

Table 5. Plant and animal species and levels of endemism by island ... 26

Table 6. Three scenarios for forest sector development 2006-2025 ... 31

CH APTER I . I N TROD UCTI ON

I.1. For e w or d

a. Forestry development is done based on principles of benefit and sustainability, community, justice, unity, transparency, and integrity with the purpose achieving the greatest possible fair and sustainable prosperity for the public.

b. In accordance with Act no. 41/1999 concerning forestry, the goal of forestry development is to:

1) Guarantee the existence of forests with adequate area and coverage that is proportional;

2) Optimize various functions of the forest and its ecosystem including its waters which include conservation, protection, timber and non timber production, and environmental services functions in order to achieve social, cultural, and economic benefits that are balanced and sustainable.

3) Increase watershed (DAS) support capabilities. 4) Encourage community participation.

5) Ensure an equitable and sustainable distribution of benefits.

c. To support the goal of forestry development, policies and guidance are required. These must be formulated in an integrated and comprehensive planning mechanism. This should be in the form of a long term plan which takes a macro perspective and more technical and operational medium-term and annual plans. d. Forestry development is an integrated part of national development; hence forestry

planning processes is an inseparable part of national development plans.

e. National development planning is based on Act no. 25/2004 concerning the National Development Planning System. Forestry sector development planning, aside from referring to the above law, also refers to Government Regulation No. 44/2004 concerning Forestry Planning and to Government Regulation No. 20/2003 concerning Government Work Plans.

f. The Forestry Development Plan also refers to the vision for a future Indonesia which is laid out by MPR Decree No. VII/2001 and the Indonesian Development Vision and Mission for an Indonesia that is safe, just and prosperous.

g. To realize forestry development in a consistent, flexible, and sustainable manner, a long term forestry development plan is needed. This plan must include a vision, missions, targets and directions for forestry sector development over the next 20 year period (2006-2025).

I.2. Definition

a. The forestry RPJP 2006-2025 is a long term forestry sector planning document. It is an elaboration of the forestry management goals set out in Act No. 41 Year 1999, of the vision and mission for a future Indonesia, and of the development vision of a safe, just, and prosperous Indonesia, with a vision and direction for forestry sector development over the next 20 years.

b. The forestry RPJP 2006-2025 is an inseparable part of national long term development plans as stated in the National RPJP 2006-2025.

c. The forestry RPJP 2006-2025 is compiled for the national level to be used as reference for the forestry medium-term development plans, at all levels (national, provincial, regency/municipality and to be used as reference for other forestry macro activity plans.

I.3. Purpose and Goal

The Forestry RPJP 2006-2025 is established with the purpose of providing a guide and reference for all forestry stakeholders to realize the goal of forestry development in accordance with the mutually agreed development vision and mission.

The goal of this Forestry RPJP is to maintain consistency in the management of forestry development from one period to the next in accordance with forestry resources management principles, without being affected too much by political change or other non-technical influences.

I.4. Legal Basis

The legal basis for the Forestry RPJP 2006-2025 is as follows:

a. Act Number 25 Year 2004 concerning the National Development Planning System; b. Act Number 41 Year 1999 concerning Forestry.

c. Act Number 32 Year 2004 concerning Regional Government;

d. Act Number 5 Year 1990 concerning Natural Resources and Ecosystem Conservation;

e. Act Number 24 Year 1992 concerning Spatial Planning;

f. Act Number 5 Year 1994 concerning Ratification of the Convention on Biodiversity;

g. Act Number 6 Year 1994 concerning the Ratification of the Convention on Climate Changes;

h. Act Number 23 Year 1997 concerning Environmental Management;

j. Government Regulation Number 44 Year 2004 concerning Forestry Planning;

k. Government Regulation Number 34 Year 2002 concerning Forest Spatial Arrangement and the Compilation of Forestry Management, Forest Utilization, and Forest Area Usage Plans;

l. Government Regulation Number 68 Year 1998 concerning Nature Conservation Area and Nature Reserve Area;

m. Government Regulation Number 35 Year 2002 concerning Reforestation Funds; n. Government Regulation Number 47 Year 1997 concerning National Spatial

Planning Plans;

o. Government Regulation Number 25 Year 2000 concerning Governmental Authority and Provincial Authority as Autonomous Regions;

p. Government Regulation Number 45 Year 2004 concerning Forest Protection.

I.5. Assumptions

In order to create realistic long-term targets of forestry development several basic assumptions are made. These assumptions are used as considerations in the analysis of various strategies. The basic assumptions include the following:

a. Forestry development occurs normally and receives political support from various sectors and stakeholders.

b. The main driving force of the forestry sector is fully committed to implementing forestry development.

c. Forestry development stakeholders are actively involved in planning, monitoring and evaluating the Forestry RPJP.

d. National security and political, social and economic stability are maintained. e. Forestry sector development receives adequate financial support.

I.6. Forestry long term development planning formulation process

The compilation of the Forestry RPJP is done in a transparent, participative, integrated and responsible manner in reference to Act Number 25 Year 2004 concerning National Planning Systems and Act Number 41 Year 1999 concerning Forestry as well as other related laws.

Source: Pusat Informasi Kehutanan

Figure 1. Indonesia’s biodiversity

CH APTER I I . TH E STATE OF FORESTRY UN TI L 2 0 0 4

II.1 Forest Resources

a. Biodiversity

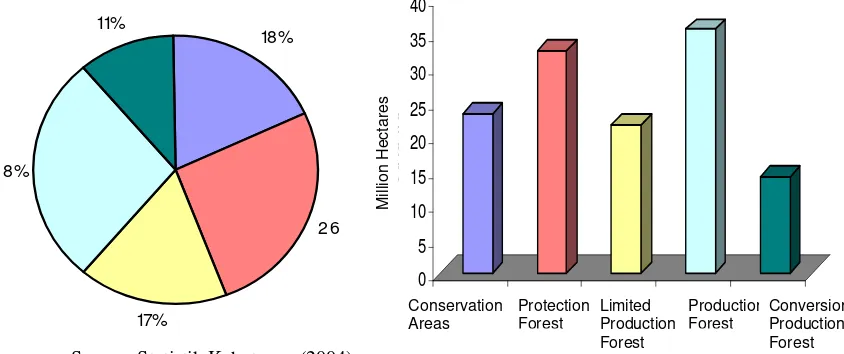

As of 2005, the government has designated 126.8 million ha as Forest Area. Of this area 23.2 million ha are classified as conservation forest, 32.4 million ha are classified as protection forest, 21.6 million hectares are designated as limited production forests, 35.6 million hectares are designated as production forest, and 14.0 million hectares are designated as conversion forest.

Indonesia is among nations with the highest levels of biodiversity, or third after Brazil and Columbia. This is reflected in the amount of biodiversity that Indoensia has which includes: 515 mamal species (12% of all mamal species in the world), 511 reptile species (7.3% of all reptile species in the world), 1,531 bird species (17% of all bird species in the world), 270 amphibian species, 2,827 invertebrate species, and 38,000 plant species (IBSAP,2003) (Figure 1).

In an effort to save this natural wealth the government has put in place Government Regulation No. 7 year 1999 on the Preservation of Wildlife and Plant Life which places 57 threatened plant species and 236 threatened wildlife species under protection. Furthermore, to regulate the global trade of endangered plants and wildlife, Indonesia is a signatory to CITES and has registered 1,049 plant species and 603 wildlife species under the treaty’s Appendix I and Appendix II. Indonesia is also a signatory and active member of the Convention on Biodiversity (UN-CBD), the Convention on Climate Change (UN-FCCC), the Convention on Land Degradation (UN-CCD), and the Convention on Wetland Conservation (RAMSAR).

However in regards to forest and forest ecosystem management, Indonesia continues to experience many problems

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 2. Development of Indonesia’s protection zones by size (left axis) and number (right axis)

ti 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18

94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 Years Mi ll io n h e c ta re s 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 uni ts

The cumulative extent of national parks The cumulative extent of nature recreational parks designations, natural disasters, and forest fires. Forest fires in 1997/1998 involved a total land area of 5.2 million ha and is recorded as the most extensive tropical forest fires of the 20th century. In 2004, degraded Forest Area amounted to 59.17 million ha, while critical land outside Forest Area amounted to 41.47 million ha. Some of this land is scattered along the 282 river watersheds that have been prioritized for rehabilitation.

In order to maintain Indonesia’s ecosystem and biodiversity, by 2004 the government had declared land and sea conservation areas in the following amount : 50 units of National Parks (Taman Nasional, TN), 116 units of Natural Parks (Taman Wisata Alam, TWA), 18 units of Forest Parks (Taman Hutan Raya, TAHURA), 14 units of Game Parks (Taman Buru, TB), 228 units of Preservation Areas (Cagar Alam, CA), and 76 units of Wildlife Sanctuaries (Suaka Margasatwa, SM) ( Figure 2 ).

Aside from this, preventative and suppressive forest security operations are conducted to protect the ecosystem and the biodiversity by combatting illegal logging activities, forest clearing activities and activities that lead to forest fires. Within the last 5 years (2000-2004), the government has conducted land and forest rehabilitation efforts in the form of reforestation activities on 469,256 ha located within the Forest Areas, and reforestation (or regreening) on 1,785,149 ha of land located outside of the Forest Area, including community forests. These efforts still fall short of expectations, hence in the next five years the government aims to rehabilitate Forest Areas and ecosystems in the amount of 5 million ha through the National Forest Rehabilitation Movement (Gerakan

Rehabilitasi Hutan, GERHAN), to establish 5 million ha of plantation forest, and to create 2 million ha of private forests (hutan rakyat).

b. Demographic and cultural considerations

Indonesia’s population in 2003 was 219.9 million people (BPS, 2005). Around 48.8 million Indonesians live in and around the Forest Area and among these, around 10.2 million people are classified as poor (CIFOR, 2000 and BPS, 2000).

Source: Pusat Informasi Kehutanan

Figure 3. Community honey bee production.

Generally communities in and around the Forest Area have less access to quality infrastructure, education, health services, and housing than urban communities. Housing and environmental sanitation as well as public facilities are also inadequate.

Forest resources are important for communities in and around forests. This is manifested in the culture of communities which places traditional values (local wisdom) derived from the interaction of people with forest resources. However, changes in forest conditions and opening of access to forest resources lead to friction within the cultural value system with regard to the forest and its ecosystem.

The Government has made extensive efforts to maintain the cultural conditions of communities in and around forests, including efforts to accommodate community rights in forest management through forestry regulations and laws.

c. Economic considerations

Commercial exploitation of natural forests began in 1967 and was one of the main drivers of the Indonesian economy from 1980 to 1990. During this period, Indonesia secured substantial global market share in tropical timber products through its exports of logs, sawn timber, plywood and other timber products.

This decline was accompanied by a decline in the number of natural forest concessions (HPH) from 575 in 1993 to 287 in 2004 (Figure 5).

Nominal government forestry revenue from the reforestation fund (Dana Reboisasi/DR), IHPH/PSDH and IHPH fees fluctuated between IDR 3.33 trillion (1999) and IDR 4.01 trillion (2004) (Figure 6).

Source: SMCP-GTZ (2004) and BPS (2005)

Figure 4. Forest products exports (left axis) and contribution to GDP (right axis) up to 2003

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 5. Natural forest concessions (HPH) until 2004

-1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 5.0 6.0 7.0

85 89 90 97 98 99 00 01 02 03

Years Bi ll io n US D -0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0 4.5 G ros s D om e s ti c P rod uc t (G D P )( % )

Export Value Billion USD GDP (%)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04

Years M ill io n H e c ta re s 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 Un its

According to Simangunsong (2004), the level of employment in the forestry sector reached a peak in 1997, when it accounted for 338,000 workers, or around 1.23% of the Indonesian labor force. During the period following the economic crisis (1997- 2002) this amount fell to 1% (Figure 7).

The actual amount of labor absorbed by the forestry sector is much larger if small scale industries, such as small scale sawn timber, furniture, agroforestry and non timber forest production are included.

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 6. Forestry revenues, 1999 to 2004 (trillion Rp).

Source: Simangunsong, GTZ (2004)

Figure 7. Employment in the forestry sector until 2002

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140

80 85 89 90 97 98 99 00 01 02

Years

Un

it

s

Planting Forest Forest Concessionaries Sawn Timber Industry

Plywood Industry Pulp and Paper Industry

3.

330

3.

020

3.

305

2.

929

2.

723 4.010

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0 4.5

99 00 01 02 03 04

Years

T

ril

lio

n

Different from Simangunsong (2004), national statistics report that the amount of labor absorbed in forestry industries and forest businesses in 2000 was 3.1 million people, with an average annual income of IDR 7.3 million per person for those working in Forest Concession (HPH) and IDR 3.3 million per person for those working in processing industries (BPS, 2000).

In general forestry has played a major role in regional development through logging roads which provide access to remote areas for local communities, through the provision of work opportunities, and through an increase in regional government and community income.

II.2. Strategic environmental conditions

a. Forestry decentralization

Act Number 22/1999 on Regional Autonomy largely shifted authority for the coordination of regional level government programs from provincial to regional governments. This has obvious implications for forestry sector development programs. Regional governments have greater authority in implementing forest related programs including technical assistance, and forest development financing, giving the regencies greater authority in carrying out sectoral programs.

However, because regional governments have been given increased authority while their capacity is still underdeveloped, implementation of sectoral and area programs have been slow. Also, without coordination being undertaken by provincial governments, communication between the central and regional government has not been smooth.

To anticipate this situation, the Center for Regional Development Control (Pusat Pengendalian Pembangunan Regional, Pusdal) was established to coordinate and communicate forestry programs between regional, provincial and central governments. In 2005 the government had established four Pusdal (Sumatra, Java and Nusa Tenggara, Kalimantan, and Eastern Indonesia Region).

Other sectors also face coordination difficulty in development and this created pressure to replace Act No. 22/1999 with Act No. 32/2004. This newer regulation does not segregate the authorities of regional, provincial and central governments but requires a common effort in administering national governance. This is based on three main principles: 1. Government Efficiency;

2. Externalities; 3. Accountability

The unique characteristics and priorities of each region complicate the integration of regional and central level programs. For this reason the decentralization process is carried out in phases, taking into account the capacity of each region.

b. Decentralization of fiscal policy

Together with the Regional Autonomy Law, the government issued Act No. 17/2003 concerning State Finances and Act No. 33/2004 concerning Fiscal Balance between the Central Government and Regional Governments. The budget allocation between central and regional governments generally takes place through the allocation of General Funds Allocation (Dana Alokasi Umum/ DAU) and Special Allocation Funds (Dana Alokasi Khusus/ DAK) as well as tax and natural resources income sharing.

The amount of DAU allocated to regions is determined by factors that include the area, population, building material price index, poverty level, regional GDP, natural resources index, and human resources index of the respective region. The amount of regional DAK is determined by the amount of revenue generated from the exploitation of natural resources in the region. Thus the amount of DAK allocated to a region and revenues generated from natural resources exploitation in the region are correlated, without terms that require these funds to be reinvested in the natural resources sector from which they derived.

At the same time, current regulations allow regional governments to explore means of generating additional funds (Local Revenue/Pendapatan Asli Daerah/PAD) through levies on revenues generated from sectoral activities such as forestry, mining and transportation.

This fiscal framework will have significant impacts on forestry sector development. In order to maximize their allocation of DAU, DAK, and PAD, regions will have the incentive to exploit their forest resources to the greatest extent possible. The sustainability of this income will depend on the sustainability of the forest utilization. As long as natural resource exploitation can be done based on principles of sustainability, regional revenue can be maintained and even increased.

c. Legal reform and law enforcement

The three main national development strategies until 2009 are: 1) 6.6% annual national economic growth; 2) development of the real sector; and 3) revitalization of agricultural development and rural economies. These strategies require simple regulations that facilitate national economic growth. For these regulations to be successful good governance along with strong and consistent law enforcement will be required.

To reduce forestry bureaucracy, and to promote national economic development, the government issued an Investment Climate Enhancement Policy Package (Presidential Instruction No. 3/2006). It was hoped that this package would lead regions and sectors to initiate legal reforms that would be in favor of investors, the public at large, and especially poor communities.

In the forestry sector, the government has identified several cross-sectoral regulations, including Government Regulations and Ministerial Decrees/Regulation issued by the Minister of Forestry, that are overly bureaucratic. However, the legal reform process will be time consuming and will depend on the central and regional governments’ ability to implement good governance and coordination of legal reforms. This in turn will depend on successful law enforcement and control from the stakeholders in the forestry sector.

d. Global commitments

Global attention will continue to be focused on the development of Indonesia’s forestry sector. Globally, forest management principles were agreed upon during the Earth Summit in 1992. These principles were elaborated in various conventions and agreements including the Convention on Biodiversity (UNCBD, 1992), the Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD, 1994), the Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, 1994), the Kyoto Protocol (1997), the United Nation Forum on Forests/International Arrangement on Forests (UNFF/IAF, 2006) and the International Tropical Timber Agreement (ITTA, 2006).

Forestry development will be indirectly affected by other conventions such as the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES, 1978), the Convention on Wetlands (RAMSAR, 1971) and global trade agreements.

Global commitments and agreements have a direct bearing on Indonesian forestry development and stakeholders need a clear understanding of these, so that Indonesia can benefit from membership in these conventions.

II. 3. Strategic issues for forestry development

a. Good governance

Forestry sector development requires good government that is free from corruption, efficient, transparent and participative in program and policy making, and also consistent in implementing those policies. Furthermore, public policies and programs must be accountable to the public.

-50 100 150 200 250 300 350

84 86 88 90 92 94 96 98 00 02

Years

10

00 hec

tar

e

s

Succeed Implemented Planned

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (1984-2003)

Figure 8. Planned versus achieved reforestation (1984-2003).

(40% 3-year survival rate is assumed for plantedtrees) This could be through supervision as well as assistance in assuring that an agreed level of government performance can be achieved.

Furthermore, there is a need for regulations that provide incentives for government officials to perform well, and

disincentives for poor performance. These regulations must be accompanied by consistent law enforcement so that poor performance can be detected and corrected early on.

Weak governance has, among other things, led the government to achieve a low level of success in carrying out the rehabilitation of land and Forest Areas during the last 20 years (Figure 8). Therefore, good governance is an important issue in future forestry development.

b. Tenure

According to Act No. 41/1999 concerning Forestry, forest lands that have been designated by the government as Forest Area are under the authority and management of the Ministry of Forestry. This regulation is in line with Article 33 of the 1945 national constitution, which mandates that “the land, the waters and the natural riches [of Indonesia] shall be controlled by the State and exploited to the greatest benefit of the people.

Article 67 of Act No. 41/1999 mandates the government to issue government regulations to manage and guarantee the rights of customary communities living in the Forest Area and whose existence has been acknowledged. Also, the Basic Agrarian Law (Act No. 5/1960) guarantees the claims of customary communities living in the Forest Area.

A lack of clear regulations on the settlement of conflicts over forest land management between communities and state-appointed parties has led to controversy over recognition of ownership rights. More issues in this respect surfaced as the government attempted to promote communication between parties with an interest in resolving these tenure issues.

c. Spatial management

Sustainable national development, aside from requiring resources, requires sufficient land area to accommodate housing, farming, urban, agricultural, transportation, mining and other needs. These needs will be met stepwise through the conversion of forest land to non forest land.

According to Act no. 24/1992 concerning Spatial Planning, land allocation is carried out through spatial land use delineation processes in each province and regency. This is done through technical reviews and analysis of local sectoral land requirements. The end result is often determined through consensus among relevant sectors.

By the end of 2005, the government had delineated spatial management plans for 31 out of the 33 provinces of Indonesia. The spatial management plans of the remaining provinces, Riau and Central Kalimantan, are in the completion phase. However, few of the 440 regencies of Indonesia have developed regency spatial management plans.

The other factor that brings spatial management issues to the surface is the regulation which has been elaborated in Article 21 sub article (4) and Article 22 Sub Article (5) Act Number 24 on Spatial Management. This law calls for reviews of spatial management plans of provinces and regencies to be carried out every five years. However, in line with increasing efforts to promote regional development in the last five years, provincial and regency divisions have occurred all over Indonesia creating difficulty in implementing spatial management policies.

Complexity and lack of clarity in provincial and regency level spatial management has created uncertainty in land allocations, which obstructs government efforts to optimize the forest sector’s functions as a driver of the economy and as a livelihood support system.

Also, territorial issues often arise with neighboring countries in border areas. These

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 9. Area of the Forest Area cleared up to 2004. Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004) ; the line indicates annual forest clearance, the area indicates the cumulative loss. 0

1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000

97 98 99 00 01 03 04

Years

100

0 hec

tar

neighboring countries, are becoming priority areas. This requires a new approach to dealing with border areas, and bilateral agreement on the spatial management of these areas will be necessary to accelerate their development.

d. Forest management

Indonesia’s forests were first formally managed by the Dutch colonial government. Forest management began in Java as well as in some of the other regions. After self-rule, intensive forest management was extended outside of Java through Forest Concession Rights (Hak Pengusahaan Hutan, or HPH), starting in the mid-1960s. The underlying forest management principles were gradually refined and were applied through various management regimes including the Indonesian Selective Felling System (TPI) and the Indonesian Selective Felling and Planting System (TPTI). However, these regimes were not properly followed. As a result, the quality and quantity of forest resources and forest ecosystems gradually declined in almost all Forest Areas in Indonesia.

By the end of 1980, in an effort to maintain timber production levels, the government launched an industrial plantation program (Hutan Tanaman Industri, or HTI). However, because of low plantation performance, the HTI effort did not help in slowing the decline in Indonesia’s timber production. By 2004, the total land area of HTI plantations was only 3.25 million ha or 56% of the 5.8 million ha target which was set in 1994. According to felling licenses issued, the production of HTI plantations reached only 7.33 million m3 in 2004 (Figure 10).

Timber production from natural forests continued to decline from 27.56 million m3 in 1987 to 5.14 million m3 in 2004 of which 3.51 million m3 came from HPH concessions

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

1986 1993 1998 2003

Years

M

illi

o

n

h

e

c

ta

re

s

Kum. Luas Perijinan Kumulatif Penanaman Rencana Penanaman

Cumulative License Areas

Cumulative Planting Areas

PlantationPlanning

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

and 1.63 million m3 came from conversion areas (IPK). The number of HPH concessions and associated industries also declined from 538 in 1987 to 287 in 2004 (Figure 11).

The decline in timber production followed a reduction in the quality of natural forest ecosystems in Indonesia which also led to a decline in production of non-timber forest products (Figure 12).

The uncontrolled extraction of timber from natural forests and large-scale conversion led to a build up of flammable material on forest floors, which has caused an increase in the frequency of forest and land fires. Global warming has exacerbated this problem (Figure 13).

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 11. Roundwood production from HPH up to 2004

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 12. Production of non-timber forest products up to 2004

-2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000 10,000

95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02

Years

D A M A R K OP A L

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

84 87 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04

Years

M

ill

io

n

m

To reduce the rate of forest ecosystem degradation, the government has made certification mandatory for concession holders and has created a more conservative exploitation system. However to date, these efforts have not achieved positive outcomes as there are indications of extinction over 100 species in Indonesia, including species of Dipterocarpaceae, Ramin (Gonistylus spp.) and Merbau (Intsia bijuga and I. palembanica) (IUCN, 2000; CITES, 2004, 2000; CITES, 2004; CITES Plan Committee, 2004).

e. Forest industries

In the mid-1970s forest industries expanded, largely through accelerated production of sawn timber and plywood made from natural forest timber. In the following decades, the plywood industry underwent rapid expansion and Indonesia became the main global plywood producer (Daryanto 2006).

However, declining timber production from natural forests in the mid-1990s and an increased attention to sustainable forest management, led the forest industries to shift to planted timber sources for production of pulp, paper board, panels, sawn timber and furniture (Simangunsong, 2004, Table 1).

Table 1. Production capacity changes of Indonesia’s forestry industries 1985-2002 (million m3)

Indsutry and Installed Capacity Production

Year

Sawmill Plymill Pulpmill Papermill Sawnwood Plywood Pulp paper

1985 8,8 6,3 0,0 0,9 7,1 4,6 0,0 0,5

1989 10,6 10,1 0,7 1,5 10,4 8,8 0,5 1,2

1990 10,8 10,2 1,0 1,7 9,1 8,3 0,7 1,4

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 13. Area of forest fires up to 2004

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450 500 550

97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 Years

10

00 hec

ta

Indsutry and Installed Capacity Production Year

Sawmill Plymill Pulpmill Papermill Sawnwood Plywood Pulp paper

1997 11,6 9,8 4,3 7,2 7,2 9,6 3,1 4,8

1998 11,0 9,4 4,3 7,5 7,1 7,8 3,4 5,5

1999 11,0 9,4 4,5 9,1 6,6 7,5 3,7 6,7

2000 11,0 9,4 5,2 9,1 6,5 8,2 4,1 6,8

2001 11,0 9,4 5,6 9,9 6,8 7,3 4,7 7,0

2002 11,0 9,4 6,1 10,1 6,5 7,6 5,0 7,2

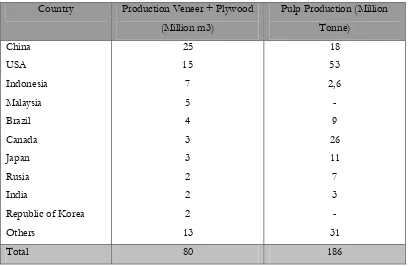

By the end of 2003, Indonesia accounted for a production of less than 10% of the global total forest production, making it lag behind the USA, Brazil, Canada and Finland. In panel production, Indonesia has been surpassed by Malaysia and the Republic of Korea. Similarly in 2004, Indonesia produced only 2.59 million tons of pulp, or less than 2% of global production (FAO, 2004, Table 2).

Table 2. Global veneer, plywood and pulp production, 2003

Country Production Veneer + Plywood

(Million m3)

Pulp Production (Million

Tonne)

China 25 18

USA 15 53

Indonesia 7 2,6

Malaysia 5 -

Brazil 4 9

Canada 3 26

Japan 3 11

Rusia 2 7

India 2 3

Republic of Korea 2 -

Others 13 31

Total 80 186

There were several reasons for the decline of Indonesia’s forest industries. Mismanagement of forest resources led to a shortage of sustainable raw material supplies. This was exacerbated by the slow development of industrial timber plantations. Other reasons include conflict over tenure with local communities, high business transaction costs

Source: Simangunsong, GTZ (2004)

which weakened global competitiveness, and inadequate infrastructural support for the industry.

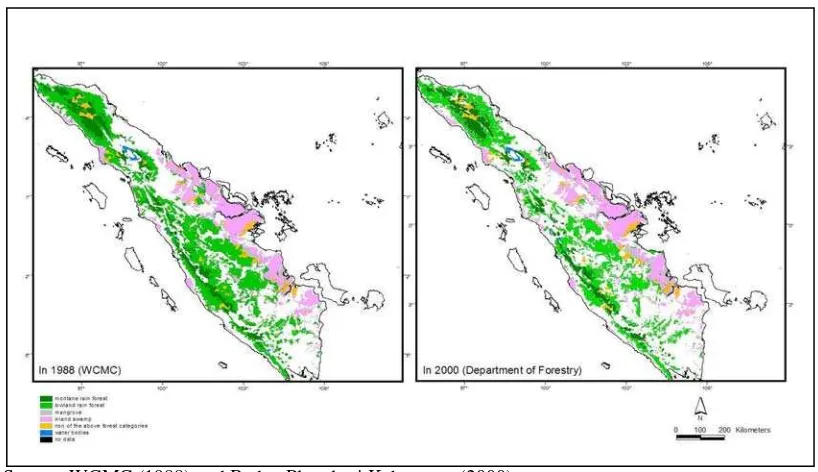

f. Degradation and conservation of biodiversity

More than 30 years of inadequate forest management practices, as mentioned above, resulted in a decline of biodiversity and degradation of the forest ecosystem. By the end of 2004, 59 million ha of the Forest Area had reportedly been degraded and the rate of forest degradation between 2000 until 2004 is estimated to be at 2.8 million ha per year (Baplan, 2004) (Figure 14).

At the same time, the number of watersheds in a critical condition increased from 36 to 282 between 1983 and 2004 (Table 3). Most watershed degradation outside Java can be attributed to mismanagement of commercial forest operations.

Table 3. Distribution of critical land in and outside the Forest Area (Million ha)

Island Critical Area

Outside the

Forest Area

Percent Critical

Area in the Forest

Area

Critical Area

Within the Forest

Area

Percent Critical

Area within the

Forest Area

Sumatera 4,35 17% 1,99 9%

Java 1,70 18% 0,37 12%

Bali - NTT 1,31 32% 0,36 11%

Kalimantan 4,57 22% 2,61 7%

Sulawesi 0,95 14% 0,97 8%

Source: WCMC (1988) and Badan Planologi Kehutanan (2000)

Island Critical Area

Outside the

Forest Area

Percent Critical

Area in the Forest

Area

Critical Area

Within the Forest

Area

Percent Critical

Area within the

Forest Area

Maluku 0,51 65% 0,18 3%

Papua 1,72 100% 1,65 5%

Total 15,11 22% 8,14 7%

The decline in watershed and forest ecosystem quality led to a decline in forest ecosystem functions. These include environmental services such as the provision of clean water for housing, industry and irrigation, and the capacity to reduce sedimentation and erosion. Habitats of some native and rare wildlife and plant species have also been lost.

Habitat loss has resulted in the extinction of several wildlife and plant species and has also given rise to conflicts between large mammals, such as elephants and tigers, with communities around forests. Between 1996 and 2004 there were more than 152 cases of tiger conflicts with communities leading to the deaths of 25 people, dozens of injuries, and the loss of hundreds of livestock (Sinaga, 2005, Figure 15 and 16).

The impacts of forest loss and degradation have forced the government to make costly investments to rehabilitate Forest Areas. In addition to foreign aid flowing into the sector, the government allocated IDR 10.51 trillion to the forestry sector over the last 15 years.

g. Poverty

Forest and ecosystem degradation lead to a decline in the capacity of people living close to forests to access natural resources. The problem is worsened by weak government

Source: BPS, Stastistik Indonesia (2002), Departemen Kehutanan, (2002)

Figure 15. Declining tiger population in Sumatra

Source : Sinaga, 2005

Figure 16. Conflict between tigers and humans

0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200

1978 1983 1988 1993 1998 2003

Years

n

um

ber

of

pop

ul

at

io

be a positive correlation between forest degradation and poverty, and poverty is not the main responsibility of the forestry sector, commercial utilization of forest areas has indirectly reduced local people’s access to forest resources (Sumarjani 2006).

Poverty is also an issue of global concern, and in 2002 international leaders agreed on the Millennium Development Goal (MDG), which aims at a 50% reduction of global poverty by 2015. Globally, poverty is also connected to the environment which is why the MDG was reconfirmed at the World Summit in New York in 2005, which stated that global efforts to end poverty can only succeed if they are integrated with efforts to address issues in forestry and the environment.

In Indonesia there are more than 10 million poor people living in and around the Forest Area (Table 4 and Figure 17).

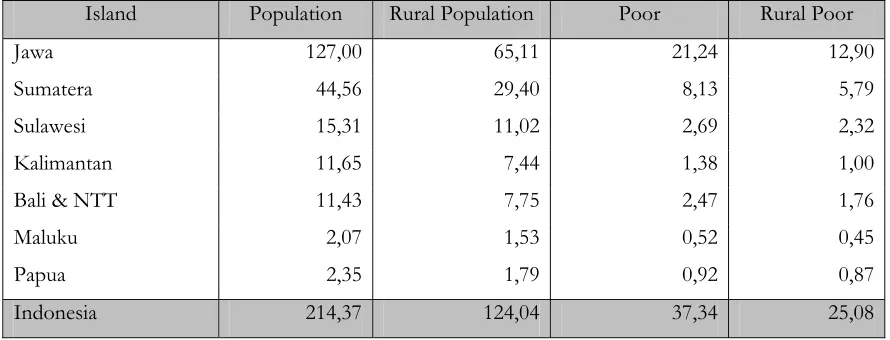

Table 4. Population and poverty distribution in Indonesia, 2003 (millions)

Island Population Rural Population Poor Rural Poor

Jawa 127,00 65,11 21,24 12,90

Sumatera 44,56 29,40 8,13 5,79

Sulawesi 15,31 11,02 2,69 2,32

Kalimantan 11,65 7,44 1,38 1,00

Bali & NTT 11,43 7,75 2,47 1,76

Maluku 2,07 1,53 0,52 0,45

Papua 2,35 1,79 0,92 0,87

Indonesia 214,37 124,04 37,34 25,08

Source: BPS, Susenas (2003)

Source: BPS, Susenas (2003) dan Departemen Kehutanan (2003)

Figure 17. Percent forest cover and rural poor

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

Sumatera Java Borneo Sulawesi Bali & NTT Maluku Papua

Pe

rc

e

n

t

However, the solution to this problem is not the sole responsibility of the forestry sector, and it must be resolved in an integrated manner with other sectors through poverty eradication programs coordinated by the Office of the Coordinating Minister for People’s Welfare (Figure 18).

h. Human resources in the forestry sector

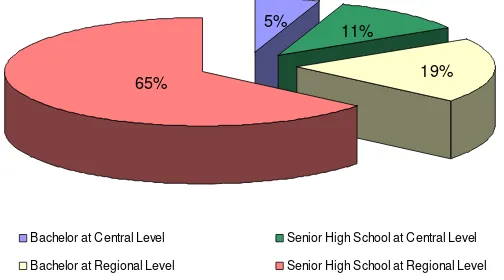

Human resources in the forestry sector are the backbone of forestry development. This requires a large number of skilled individuals with a vision for the future, who are creative, innovative, globally competitive, dedicated, and in possession of high moral standards. However, the current situation falls short of these expectations. Based on an analysis of the educational level of human resources, most civil servants (76%) in the central and regional governments only have a senior high school education (SLTA) (Figure 19).

Source: Bappenas (2003)

Figure 18. Employment classification of rural poor and non-poor, 2002

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 19. Educational level of national civil servants in forestry at

65% 19%

11% 5%

Bachelor at Central Level Senior High School at Central Level

Bachelor at Regional Level Senior High School at Regional Level

9.71 14.29 8.67 10.24 10.42 7.65

13.79

44.71 43.73 40.2

46.99 48.09 31.65

58.57

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

Productive Age Pre Productive Age Un-Employed Potential Worker Worker Unemployment Partial Unemployment

Percent (%)

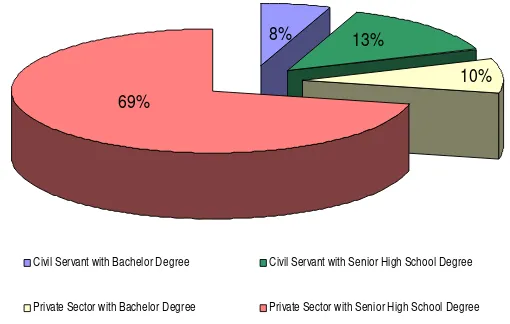

If private sector employees are included, the proportion of all employees in medium and large scale forestry industries with only a high school education would be 82% (Figure 20).

Assuming that the professional capacity of forestry workers is correlated to their educational qualification, then human resource development in the forestry sector is in need of serious attention.

i. Research and development

Forestry policy and development should be based on results of research and development so that a high level of accountability can be reached. However, limited human resources and limited capacity in research and development, has prevented this from being carried out satisfactorily.

Human resource capacity dedicated to research and development is still limited and focused on basic scientific tasks such as species inventories and short term fundamental research. Currently the Ministry of Forestry’s Research and Development Agency (FORDA) only has 26 researchers and 6 research professors. These are almost entirely stationed in central government offices, far from the Forest Area (Figure 21).

Even with this limited amount of human resources, forestry R&D is able to produce patented forestry products. However, forestry R&D support facilities are far from adequate and none of the R&D laboratories today has ISO 1725 certification.

Foreign language publications by forestry R&D are limited and this impedes promotion and networking with researchers at a global level. If R&D is to become a determining factor in the course of forestry development, serious attention needs to be given to development of human resources, research facilities and supporting infrastructure for R&D.

Source: BPS (2002) dan Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 20. Educational level of national civil servants and private sector employees, 2002

8% 13%

10% 69%

Civil Servant with Bachelor Degree Civil Servant with Senior High School Degree

j. Forestry crimes

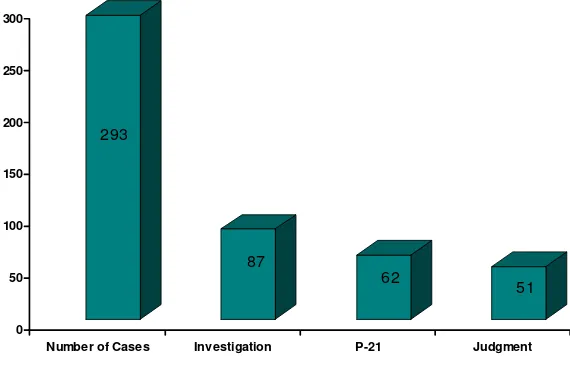

Forestry crime generally involves some form of illegal forest resource extraction and trade. This crime occurs as a result of unsustainable forest management and poor forest governance. Drivers of forest crime include demand for timber, inconsistent law enforcement, and poverty among communities living near forests (Figure 22).

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 21. Human resources in Forestry Research and Development (FORDA)

Source: Statistik PHKA (2004)

Figure 22. Results of illegal logging cases, 2003

293

87

62

51

0 50 100 150 200 250 300

Number of Cases Investigation P-21 Judgment

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450

N

u

m

be

r of

P

e

op

le

Head Quarter Regional Office

Forestry crimes also tend to be more prevalent in border areas which tend to be more isolated, less developed and poorer than other areas.

Since 1990, in an effort to reduce forestry crime, the government has conducted various forest law enforcement operations. At the global level, the government has engaged in bilateral cooperation, including the signing of an MoU with the UK, and participation in the Forest Law Enforcement and Governance (FLEG) process, in the EU Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) process and the Asia Forest Partnership (AFP). However, so far these efforts have not yielded real results, and additional efforts are needed to effectively combat forest crime.

II. 4. Forestry development potential

To achieve forest sector development, all potential development areas of the sector must be targeted, managed, and promoted. These areas include:

a. The Indonesian Forest Area

Forests are a critical natural resource for Indonesia because of their economic, social and environmental functions. In 2004, the total area classified as Forest Area was 126.8 million ha. This area is divided into classifications of conservation forest (23.2 million ha), protected forests (32.4 million ha), limited production forests (21.6 million ha), production forest (35.6 million ha), and convertible production forests (14 million ha) (Figure 23). With over 60% of land area in Indonesia classified as Forest Area, forest resources have a significant potential for promotion, management and utilization for the benefit of Indonesia’s people.

18 %

2 6

17% 8 %

11%

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

Ju

ta h

a

KSA/KPA HL HPT HP HPK

Million Hectar

es

Conservation Areas

Protection Forest

Limited Production Forest

Production Forest

Source: Statistik Kehutanan (2004)

Figure 23. Classifications of the Forest Area

b. Biodiversity

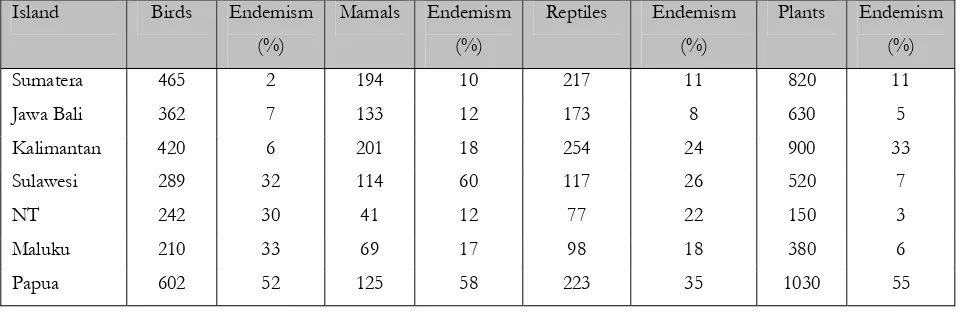

Indonesia has high levels of biodiversity which can contribute to forest sector development and national development in general (Table 5). Only a small portion of existing biodiversity in forests has been commercially exploited. Additional species should be developed for commercial exploitation. This must be done according to principles of sustainability to ensure long lasting benefits.

Table 5. Plant and animal species and levels of endemism by island

Island Birds Endemism

(%)

Mamals Endemism

(%)

Reptiles Endemism

(%)

Plants Endemism

(%)

Sumatera 465 2 194 10 217 11 820 11

Jawa Bali 362 7 133 12 173 8 630 5

Kalimantan 420 6 201 18 254 24 900 33

Sulawesi 289 32 114 60 117 26 520 7

NT 242 30 41 12 77 22 150 3

Maluku 210 33 69 17 98 18 380 6

Papua 602 52 125 58 223 35 1030 55

c. Forestry Human Resources

Only 13% of people employed in the public and private forestry sector (not including universities and NGOs) have a university level education. There are 85 people with Doctorate Degrees, 742 people with Masters Degrees, 8,210 people with undergraduate degrees, 3,743 people with college degrees and 58,101 people with a high school education. Assuming that human resource capacity will increase, this will become an important driver of forestry development (Figure 24).

Sumber: IBSAP (2003)

Source: BPS (2002) dan Statistik Kehutanan (2002)

Figure 24. Education levels of forestry employees

82%

13% 5%

d. Market demand for forestry products and services

Global demand for plywood, sawn timber, moulding, and furniture will continue to rise. In 2010 panel based timber consumption is expected to reach 320.4 million m3, or up 256% from 1990. This provides an important opportunity for the Indonesian forestry industry to supply this market demand (FAO 1990). Based on the amount of resources available, and current capacity, as well as continuing efforts to develop the forestry sector, Indonesia will be able to benefit from this opportunity (Figure 25).

e. The Clean Development Mechanism

The rate of forest degradation in the last five years was 2.8 million ha per year, and the area of Forest Area to be rehabilitated has reached 59.17 million ha. At the same time, the government’s ability to carry out rehabilitation is limited and alternative funding sources are needed.

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) is one option for financing the rehabilitation of damaged areas within the Forest Area. This mechanism has been simplified and provides incentives linked to carbon trading. Indonesia is able to offer non-forested areas that are eligible for funding through the CDM. The form of rehabilitation through the CDM can be as community or industrial forests.

However, to qualify for CDM funding, several conditions need to be met, including clear land rights. Meeting these conditions will be a challenge for the forestry sector in the future.

f. Research and development

By 2004, the Forest Research and Development Agency (FORDA) had developed various innovations that can be used to support forestry development. Among key research results is a patented palm oil processing method (right no. H3. HC. 04.02. D/5265). Timber

Source: WWW. FAO.org/FAOSTAT (2005)

Figure 25. Global import trends of forest products

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45

98 99 00 01 02 03 04

B

ill

io

n

U

S

D

from oil palms is a potential alternative source of raw material for forestry industries in the future. Other research results involve genetic engineering, bio-diesel production, mycorrhizae, and a registered computer program for a timber atlas (registration number 026347). These research results can contribute to future forestry development (Figure 26).

g. Environmental services and non-timber forest products

In addition to providing forest products, Indonesia’s forests are an important source of environmental services and services without a tangible market value. However, resource exploitation has been largely focused on timber production, while non-timber forest products and environmental services have not been managed to the fullest extent possible. Even so, from 2000 to 2004, foreign exchange revenue from plant and wildlife exports reached USD 4.17 million and USD 20.32 million respectively. Birds and nests of swallows account for 62% of foreign exchange generated by wildlife exports. Orchids account for 83% of foreign exchange generated by plant exports (Figure 27).

Source: Badan LITBANG (2006)

Figure 26. Use of oil palm timber for panel

Source: Statistik PHKA (2004)

83%

Orchid Gaharu

Pakis Daun Lidah Buaya

Sikas Ramin

62%

Mammal Reptil Amphibi Aves

Eco-tourism is another source of foreign exchange related to the forestry sector. From 1994 to 2004, over 16 million people visited national park conservation areas (Figure 28).

Source: Statistik PHKA (2004)

Figure 28. Visitors to conservation areas

-2,000 4,000 6,000 8,000 10,000 12,000 14,000 16,000 18,000

94 96 98 00 02 04

Years

V

is

it

o

r (1

0

0

0

)

CH APTER I I I . V I SI ON AN D M I SSI ON FOR FORESTRY

D EV ELOPM EN T 2 0 0 6 - 2 0 2 5

III.1 Vision

There are three scenarios for long term forestry development in Indonesia:

a. Forestry development continues unchanged;

b. National and forestry development will progress in response to market demand and social requirements;

c. Forest sector development will be supported by all sides and forestry’s contribution to sustainable development and public prosperity will increase and Indonesia’s position in the global forestry sector will rise.

Underlying the second and third scenarios is the assumption that, over the next 20 years, market demand and social needs for forest resources will increase in line with population growth in Indonesia. Also, as social awareness of forestry issues grows, there will be an increase in forestry oversight and greater civil society involvement in sustaining forest resources. Principles of sustainability in the forest sector will continue to gain importance in public perception.

For these reasons, the third development scenario has been chosen as a goal (Table 6), in the hope that forest resources, including forest ecosystems and various forest functions, will provide a basis for forestry development that:

a. Provides employment opportunities, in particular for domestic workers; b. Produces non-timber and timber forest products;

c. Fulfills the demand for non-timber and timber raw materials;

d. Provides water services for the development of the non-forestry sector; e. Provides protection from floods and droughts;

f. Maintains the quantity and quality of the forest as a life support system;

Table 6. Three scenarios for forest sector development, 2006-2025

Status Quo Scenario Forestry Development based on

high market and society demands

Forestry Development with the support of various parties

Governance

Complicated bureaucracy and public service

Escalating conflict on forest resources

Declining support from other sectors

Reformation on bureaucracy and public service

Support from other sectors and involvement from various parties are not dominant factors.

Reformation on bureaucracy and public service.

Development involving various parties

Forestry development that is integrated with other sectors

Economic Con

tr

ibution

Inefficient usage of forest resources

Declining economic contribution

Development is only

concentrated on the large-scale level.

The usage depends on market and demand.

Increasing contribution towards Gross Domestic Product.

Development still concentrated on the large-scale level.

A more efficient and

comprehensive forest resources usage.

Increasing contribution towards Gross Domestic Product.

Development will be integrated among small-, medium-, and large-scales. S o ciety We lfar

e Low contribution towards the

increase of society welfare

Low involvement in the development from societies surrounding/within forests.

Macro-economic indicators-oriented forestry development.

Commitment towards society involvement in forestry development has not yet been institutionalized.

Society-welfare-oriented forestry development

Give preference to the involvement of societies surrounding/within forests in forestry development.

Forest Resource

s Sustainabi

lity The production of forest

resources that is not sustained.

Increasing degradation of ecosystem and forest resources.

Decreasing value of ecosystem and forest resources.

Declining bargaining power in global level.

Commitment towards the fulfillment of society and market needs becomes a more important consideration

Sustained usage and forest resources’ production restoration become necessities.

Give preference to forest resources’ quality and quantity restoration efforts.

Increasing appraisal towards ecosystem and forest resources.

Improving bargaining power in global level.

Thus, if properly managed and supported by various relevant sectors, Indonesian forest resources have the capacity to become a pillar of sustained development. Based on this, the development vision for the forestry sector can be summarized as follows:

“Forestry as a pillar for sustainable development by 2025”

III.2. Mission

To achieve the above long-term vision, six forestry development missions have been established as follows:

a. To create a strong institutional framework for forestry development. This mission is established to support the harmonization of social, environmental, and economic contributions of forest resources. This requires the establishment of forest management institutions that are efficient, cost-effective, properly managed, and that have appropriate scope. Management authority needs to be decentralized yet nationally integrated and must be based on principles of sustainability.

b. To increase the value and sustainable productivity of forest resources. This is meant to guarantee the sustainability of forest resource contributions to national development. This sustainability will depend on, among other factors, the continued existence of the Forest Area, the maintained hydrological functions of watersheds, the conservation of biodiversity, and the realization of the potential value of forest resources to support sustainable national development.

c. To develop forestry products and services that are environmentally friendly, competitive, and that have a high added value. This mission is meant to encourage the development of forestry products and services, while taking into account the availability and sustainability of forest based raw materials. The forestry processing sector is expected to become more efficient through advances in research and improvements in technology, leading to greater competitiveness, less waste, less environmental impacts, and a higher contribution to GDP.

d. To develop an enabling forestry investment climate. This mission aims to develop and sustain forestry investment in the processing industry, in timber production, and in environmental services, while avoiding market distortions (monopolies and oligopolies) and illegal practices through the application of good governance and incentives. Incentives for small to medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in the forestry sector are expected to lead to increases in employment, social welfare, and efficiency, and to greater forestry contributions to the economy.

e. To increase the level of exports of forestry products and services. This mission is meant to increase the added value of forestry exports to global and regional markets. Diplomatic negotiations in overcoming trade barriers will become increasingly important for Indonesia’s forestry exports to reach high values. Increasing the value of forestry exports will restore the sector’s prominent role as a contributor of national revenue.

CH APTER I V . FORESTRY LON G TERM D EV ELOPM EN T

D I RECTI ON , 2 0 0 6 - 2 0 2 5

IV.1. Main objectives

The long term goal of the forestry sector is to increase the people’s prosperity in a sustainable and equitable manner. In accordance with this goal and the forestry development vision for 2006 to 2025, the following main objectives have been established:

a. The creation of a strong institutional framework for forestry development. This will be demonstrated by:

1). The establishment of efficient, cost-effective and accountable forest management institutions. This c