Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:18

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Personal Finance Education in Recessionary Times

Nancy Groneman Hite , Thomas Edwin Slocombe , Barbara Railsback &

Donald Miller

To cite this article: Nancy Groneman Hite , Thomas Edwin Slocombe , Barbara Railsback & Donald Miller (2011) Personal Finance Education in Recessionary Times, Journal of Education for Business, 86:5, 253-257, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.511304

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.511304

Published online: 21 Jun 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 405

View related articles

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.511304

Personal Finance Education in Recessionary Times

Nancy Groneman Hite, Thomas Edwin Slocombe, Barbara Railsback, and Donald Miller

Emporia State University, Emporia, Kansas, USA

The authors report the status of personal financial education in light of the recent economic crisis from the perspective of secondary school business teachers. Results showed that in the state of Kansas, 20% of the schools required a personal finance course prior to high school graduation, with 12% considering such a requirement. The recession has had a small but positive impact on personal finance enrollments and graduation requirements. Overall, 20% of the schools in this state were not complying with the state mandate to teach financial literacy. The demographic similarities between Kansas and the rest of the United States suggest a widespread need for additional financial literacy education.

Keywords: consumer education, financial literacy, personal finance, recessionary impact

The present recession is widely considered the worst this country has experienced since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Its tragic outcomes include severe unemployment, decimated retirement accounts, and the unavoidable need to alter saving and spending patterns. The present subprime mortgage situation, which triggered the global financial dis-aster, might have been caused by low levels of financial literacy among consumers (Campbell, 2006); it should be considered a wake-up call for teaching financial literacy at all levels of education.

Personal financial competency is an essential ingredient for successful living in the 21st century. The 2009 National Foundation for Credit Counseling (NFCC) Financial Liter-acy Survey noted that 41% of adults living in the United States graded themselves as “C” or lower on their personal finance knowledge (National Foundation for Credit Counsel-ing, 2009). Increasingly, individuals encounter greater com-plexity in conducting financial affairs and making decisions that affect not only themselves and family members. Al-though financial documents have become more complex, individuals’ social environment places greater emphasis on immediate gratification of consumer wants and needs. There-fore, personal finance acumen is vital to making choices that will be beneficial in the longer term.

Correspondence should be addressed to Nancy Groneman Hite, Emporia State University, Department of Business Administration and Education, 1200 Commercial Street, Campus Box 4058, Emporia, KS 66801, USA. E-mail: nhite@emporia.edu

Personal finance topics are commonly included in sec-ondary education curriculums, but less frequently in elemen-tary curriculums and undergraduate programs. Regardless of when it is taught, evolving financial practices are extremely relevant for today’s young people. For example, family finan-cial practices are impacted by the emerging usage of debit cards, growth of e-commerce, and greater government in-volvement in the student loan arena. Increasingly, employees are challenged to assume greater responsibility for manag-ing their own retirement programs, understandmanag-ing changmanag-ing health-care guidelines, and making adjustments when Social Security regulations change.

In 2007, only seven states required students to take a per-sonal finance course or to include perper-sonal finance within an economics course as a high school graduation requirement; that number increased to 13 states in 2009 (National Council on Economic Education, 2009). However, state requirements to teach personal finance are not necessarily indicative of the changes happening at the local school district level—changes that may be demanded by parents who have experienced fi-nancial crises in recent years. This preliminary study was conducted to determine the impact the recession has had on financial literacy education and to determine the status of financial education in the K–12 schools in Kansas with the belief that if positive changes have occurred in this state, there may be changes occurring in other states, and that fur-ther research is needed. Presently, Kansas requires financial literacy be taught in Grades K–12 in public schools “within the existing mathematics curriculum or another appropriate subject-matter curriculum” (Personal Finance Literacy, 2003, p. 1). If the law is having the intended effect, such legislation

254 N. G. HITE ET AL.

could and should be emulated by other states. However, if the law is not being followed, the content of the legislation should be scrutinized, and further investigation is needed.

Review of Literature

During the last century, the popularity of personal fi-nance courses has risen and fallen several times (Hosler & Meggison, 2008). In this century, interest has increased again with advocates arguing for improvements in the financial lit-eracy of young people (Morton, 2005). One advocate, the former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, stated, “improving basic financial literacy at the elementary and sec-ondary levels will provide a foundation of financial literacy that can help prevent young people from making poor de-cisions that can take years to overcome” (Greenspan, 2005, p. 65).

Traditionally, financial literacy has been taught in sec-ondary schools, even though one study reported secsec-ondary education courses in personal finance may not improve immediate financial literacy (Mandell & Hanson, 2009). Some other research studies have indicated mixed results from financial literacy instruction. A study of undergraduate students (Mandell & Hanson) found that personal finance courses taken in high school have little positive impact on the financial literacy of college students. A study of students in Grades 5–9 who were provided personal savings instruc-tion through live play and classroom instrucinstruc-tion showed that learning and attitude change were significant and inversely related to age with the greatest gains in knowledge being attained by younger children (Mandell, 2009).

However, several research studies have shown that fi-nancial knowledge can be increased through fifi-nancial lit-eracy education. A study of high school students found that as little as 10 hours of classroom instruction pro-duced significant knowledge and behavioral changes (Danes, Huddleston-Casas, & Boyce, 1999). A different study com-pared students’ results on a financial practices index based on self-benefiting behavior in cash flow management, credit management, and savings and investment practices to stu-dents’ scores on a financial literacy quiz (Hilgert, Hogarth, & Beverly, 2003). Results showed a positive relationship be-tween the students’ financial literacy scores and their index scores indicating that financial knowledge is related to self-benefiting financial practices.

Education is not the only factor that can influence mak-ing effective financial decisions. Results of a literacy quiz given to high school students in Indiana found that several economic socialization factors have a positive impact on fi-nancial literacy: working 10–20 hr per week, having a savings account, and being from a family with an income between

$50,000 and$75,000 (Valentine & Khayum, 2005).

Most people agree that financial literacy must be taught in the nation’s schools, but there is less agreement on the approach and the content to be covered. Vitt (2009)

recommended a two-pronged approach—teaching personal financial literacy (knowledge) and trying to mold future fi-nancial behavior. Effective teaching within a personal finance course is more than simply providing basic knowledge at the lower cognitive levels; it must also include behavior manage-ment techniques that can be employed in the future (Vitt).

In terms of financial literacy content, two main sets of curriculum standards provide guidance to educators. Gayton (2005) correlated those two sets of curriculum standards and found that Jump$tart’s money management standard

corre-lated with seven of the eight National Business Education Association standards, the highest of any of the Jump$tart

standards. However, he found that two Jump$tart standards,

income and spending and credit, did not align well with any of the National Business Education Association (NBEA) standards.

In terms of personal finance concepts, students should have a working knowledge about credit and debt, budgeting, savings, an understanding of investments and compound in-terest, needs and wants, planning for retirement, taxes, and career education (Vitt, 2009). Additional concepts should include personal and household finance basics, information about social security laws, and insurance (Atchley, 1998).

Personal finance behavioral instruction should include learning how to make rational financial decisions, such as cost consciousness and the development of early savings habits as well as developing personal values, such as in-ner, social, physical, and financial values (Vitt, 2009). Those personal values can be taught more effectively through role-playing and modeling than lecturing (Vitt).

Because financial literacy is taught at a variety of grade levels, the question of teacher competence in terms of con-tent and teaching methods arises. Personal finance teachers should have a background in the content they are teaching, but Atchley (1998) found that many teachers in Grades K–8 have never taken a personal finance course themselves.

Personal finance concepts can be found in state educa-tional standards in 44 U.S. states, and 34 states require per-sonal finance content to be implemented in the curriculum (National Council on Economic Education, 2009). Fifteen states require either a stand-alone personal finance course or an economics course (including personal finance) be offered at the secondary level. A search of the present literature does not indicate the grade levels at which financial literacy is usu-ally taught, the type of teachers given the responsibility to teach it, or the impact the recent recession has had on course offerings and enrollments.

Research Questions

This study was designed to answer the following research questions:

Research Question 1:How has the recent recession impacted personal finance education?

Research Question 2:What is the present status of financial literacy education in K–12 schools in terms of depart-ments responsible for teaching it, financial literacy topics taught, and course delivery methods utilized?

Research Question 3:Are there differences in the numbers of schools teaching financial literacy based on school dis-trict classification—urban, rural, or suburban schools?

METHOD

The goal of this study was to learn how the present eco-nomic recession is impacting financial literacy instruction. The data were collected from high schools throughout the en-tire state of Kansas because Kansas is similar in many ways to much of the United States. In fact, it is within 1% of the rest of the United States in numerous demographics, includ-ing persons under 18 years of age, adults 19–64 years of age, women in the household, adults with children in household, U.S. citizenship, white collar workers, permanent workers in the workforce, persons having bachelor’s degrees or higher, and female-owned businesses (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Home ownership is only 3% higher in Kansas than in the rest of the country, with median household income slightly lower,$50,174 in Kansas, as compared to$52,029 nation-ally. Although it would be desirable for future researchers to collect data in other parts of the country, the similarity be-tween Kansas and U.S. demographics suggests the findings of this study may provide insight into trends in other parts of the country.

A survey form of descriptive research was used to de-termine business teachers’ perceptions of personal financial education. A printed survey was mailed to high school busi-ness teachers because many high school busibusi-ness education departments teach personal finance courses.

A literature search revealed no survey instrument that ad-dressed the relevant questions in this study; consequently, a questionnaire was developed by the researchers. The ques-tionnaire was pilot tested with eight practicing business teachers at private high schools in Kansas to solicit their recommendations related to readability, content, and length. Their recommendations were incorporated into the revised survey instrument that was sent to the entire population of 325 public high schools in Kansas rather than a sample of schools. A total of 122 usable responses were received from the first mailing for a response rate of 37.5%. Given an ac-ceptable response rate, no follow-up requests were mailed to the respondent group.

The survey questions focused on the impact of the re-cent recession on personal finance course enrollments and course offerings as well as the status of financial literacy education in school districts. Because responses could be classified into nominal categories, the chi-square statistical test was utilized to determine if significant differences ex-isted for various comparisons. This nonparametric statistical

technique examines the relationship between observed and expected frequencies of occurrence. Nonparametric statisti-cal methods do not make stringent assumptions related to the nature of parameters of a distribution. Data were tabulated, and the subsequent analysis was completed.

RESULTS

The results of this study are presented in the following order: (a) impact of recent economic recession on the number of schools requiring a personal finance course for graduation, (b) the status of financial literacy instruction, (c) the depart-ments most often responsible for teaching financial literacy, and (d) the prevalence of financial literacy topics taught and course delivery methods used.

Out of 325 public high schools in the state, 122 business teachers representing 122 different high schools responded to the mail-out survey for a return rate of 37.5%. The following tables show that some survey questions were not filled out by all 122 teachers. Survey respondents represented urban (12%), rural (74%), and suburban (11%) schools, similar to the total number of schools in each category in the entire state.

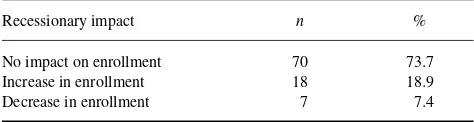

One survey question directly related to the recent sion asked business teachers their perception of the reces-sion’s impact on personal finance course enrollment at the high school level. Although nearly two thirds of the respon-dents indicated the recession had no impact on enrollment, approximately 15% indicated that enrollment had increased since the start of the recession, as shown in Table 1.

Of the 122 schools responding to the survey, 24 (20%) required a personal finance course for high school graduation. Fifteen schools (12%) were considering such a requirement in the future.

Of the schools responding to the survey, 80% of the schools offered financial literacy instruction but not neces-sarily a course. When asked at what grade level(s) financial literacy was taught, 81% indicated it was taught in Grades 9–12, with 8% indicating it was taught in Grades 5–8 and 3% in Grades K–4 (see Table 2). A chi-square test indicated there were no significant differences in the proportion of ur-ban, rural, and suburban schools offering financial literacy

TABLE 1

Impact of Recession on Personal Finance Enrollment at High School Level

Recessionary impact n %

No impact on enrollment 70 73.7

Increase in enrollment 18 18.9

Decrease in enrollment 7 7.4

Note. N=95.

256 N. G. HITE ET AL.

TABLE 2

Financial Literacy Instruction Offered, by Grade Level and School Category

Grade levels Urban Rural Suburban Total Overall %

Grades 9–12 13 76 10 99 81

Grades 5–8 1 9 0 10 8

Grades K–4 0 4 0 4 3

Note. n=114.

training at various grade levels (p >.75 for all three grade

levels).

When asked whether a personal finance course or a course with a closely related name was required for high school grad-uation in the school district, 20% of the schools responded that such a course was required; but 80% of the schools re-sponded that such a course was not required. A chi-square test indicated there were no significant differences (p =

.856) in the proportion of urban, rural, and suburban schools that required a personal finance course for high school graduation.

Of the 98 schools that did not require a personal finance course prior to graduation, 12% indicated such a requirement was presently being considered—3 urban schools, 11 rural schools, and 1 suburban school. A chi-square test indicated there were no significant differences (p=.525) in the pro-portion of urban, rural, and suburban schools considering a personal finance course as a requirement for high school graduation.

In Grades K–4 and 5–8, personal finance was taught most frequently within mathematics courses, but in Grades 9–12 it was taught most often in business departments, as shown in Table 3. Schools in Kansas do not employ business or family and consumer science teachers in Grades K–4; therefore, Table 4 indicates that information was not applicable.

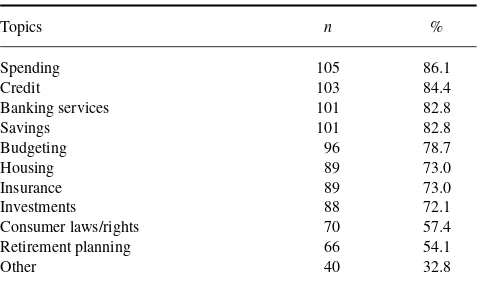

An additional survey question asked respondents to iden-tify the topics taught in personal finance courses. The topics covered most frequently in the schools surveyed were spend-ing, credit, and banking services. Consumer laws and con-sumer rights and retirement planning were taught least often (see Table 4).

TABLE 3

Departments and Subject Content Areas Most Responsible for Teaching Personal Finance

Department or subject content

Frequency of Topics Covered in Personal Finance Curriculum

Topics n %

Spending 105 86.1

Credit 103 84.4

Banking services 101 82.8

Savings 101 82.8

Budgeting 96 78.7

Housing 89 73.0

Insurance 89 73.0

Investments 88 72.1

Consumer laws/rights 70 57.4

Retirement planning 66 54.1

Other 40 32.8

Note. N=122.

Some school districts offered courses to other districts using nontraditional course delivery methods. However, the respondents to this survey indicated that personal finance courses were primarily taught using traditional face-to-face instruction, with only three schools offering it via the Internet and one offering it using an interactive video laboratory.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The recent recession appears to have had a small positive impact on financial literacy enrollments in Kansas. Since the start of the recession, enrollment in personal finance courses at the high school level has increased; in fact, 19% of the schools surveyed had enrollment increases. Because Kansas is demographically similar to much of the United States, these enrollment trends suggest a similar trend may be occurring in the rest of the country. However, further research is needed to determine whether other states have experienced similar enrollment increases and a corresponding increased interest in taking personal finance course.

A substantial percentage of schools in Kansas, 12%, are considering requiring a personal finance course for high school graduation. Presently, only 20% of the schools in Kansas indicated such a course is required prior to grad-uation. Those low numbers are similar to the results of a nationwide survey showing that only 13 states in the United States had such a requirement (National Council on Eco-nomic Education, 2009). Because of the individual financial difficulties experienced during the recent recession, legisla-tion requiring students to take a personal finance course prior to high school graduation requirement should be considered in the remaining 37 states, including Kansas. The economic reality is that schools across the country have experienced budget cuts and have let teachers go, so the addition of an-other course, as crucial as it may be at this point in time, may not occur.

Results of the survey showed that a majority of the schools (81%) offered financial literacy instruction in K–12 schools. In terms of the present status of financial literacy instruc-tion in Kansas, secondary schools are the primary providers of financial education, with very few schools offering it in Grades K–8. When taught in Grades K–8, financial education was primarily taught within mathematics courses. However, at the high school level, financial literacy is primarily taught in business departments rather than in family and consumer science, mathematics, or social science departments. Given the fact that business teachers probably have taken course-work themselves in personal finance or business finance, it is logical that business teachers would teach it.

Given the present problems consumers have had with out-standing credit card debt and low savings rates, the course topics taught most frequently (spending, credit, banking ser-vices, and savings) are entirely appropriate. However, the topics covered least often (retirement planning, consumer laws and rights, and investments) are of greater concern. Those topics are deemed vitally important for citizens to pos-sess particularly with the uncertain future of Social Security and with the huge sums of money people lost in retirement accounts invested in the stock market. Therefore, more em-phasis should be given to those topics in all personal finance classes at Grades K–12 as well as in undergraduate classes.

Chi-square tests showed no significant differences in the number of schools teaching financial literacy based on a basic classification system of rural, suburban, and urban schools. Additionally, there were no significant differences in the pro-portion of urban, rural, and suburban schools offering finan-cial literacy training at various grade levels.

Traditional face-to-face instruction is used to teach finan-cial literacy in the majority of the schools in Kansas. Further studies are recommended to determine if personal finance knowledge and behaviors can be taught effectively via the Internet or interactive video laboratories. The demographic similarity between Kansas and the rest of the United States suggests a widespread need for additional financial literacy education. With the low number of high schools offering a personal finance course in Kansas as well as many other states, it must be recognized that young adults in the United States are probably not financially literate. Additionally, if high schools are not willing to offer or require such a course, colleges should attempt to teach financial literacy possibly

by requiring personal finance as a general education course. Such a requirement may prevent some of the huge student loan and credit card debts college students incur.

REFERENCES

Atchley, R. C. (1998). Educating the public about personal finance: A call for action.Journal of American Society of CLU & ChFC,52(28), 30–32. Campbell, J. (2006). Household finance. The Journal of Finance, 61,

1591–1604.

Danes, S., Huddleston-Casas, C., & Boyce, L. (1999). Financial planning curriculum for teens: Impact evaluation.Financial Counseling and

Plan-ning,10(1), 25–37.

Gayton, J. (2005). Cross-referencing national standards in personal finance for business education with national standards in personal finance educa-tion.Delta Pi Epsilon Journal,47(1), 36–48.

Greenspan, A. (2005). The importance of financial education today.Social

Education,69(2), 65.

Hilgert, M., Hogarth, J., & Beverly, S. (2003). Household financial man-agement: The connection between knowledge and behavior.89 Federal

Reserve Bulletin,89, 309–322.

Hosler, M., & Meggison, P. (2008). The foundations of business education. In M. H. Rader (Ed.),Effective methods of teaching business education (pp. 1–20). Reston, VA: National Business Education Association. Mandell, L. (2009).Starting younger: Evidence supporting the effectiveness

of personal finance education for pre-high school students. Retrieved from http://www.nationaltheatre.com/ntccom/pdfs/financialliteracy.pdf Mandell, L., & Hanson, K. (2009, January).The impact of financial

edu-cation in high school and college on financial literacy and subsequent financial decision making. Paper presented at the American Economic Association Meeting, San Diego, CA.

Morton, J. S. (2005). The interdependence of economic and personal finance education.Social Education,69(2), 66–69.

National Council on Economic Education. (2009).Survey of the states: Economic, personal finance, & entrepreneurship education in our na-tion’s schools in 2009. Retrieved from http://www.councilforeconed.org/ about/survey2009/

National Foundation for Credit Counseling. (2009, April 28).Many

Amer-icans give themselves poor grades relating to financial literacy[Press

release]. Washington, DC: Author.

Personal Financial Literacy Programs; Development and Implementation,

Kan. Stat. Ann.§72–7535 (2003).

U.S. Census Bureau. (2000).U.S. census of population and housing 2000: Summary population and housing characteristics. Washington, DC: Gov-ernment Printing Office.

Valentine, G., & Khayum, M. (2005). Financial literacy skills of students in urban and rural high schools.Delta Pi Epsilon Journal,47(1), 1–10. Vitt, L. (2009, April).Social and emotional links to our financial behavior.

Paper presented at the Jump$tart Annual Partners Meeting by the Institute for Socio-Financial Studies, Washington, DC.