Bifurcating Time: How

Entrepreneurs Reconcile

the Paradoxical

Demands of the Job

Danny Miller

Cyrille Sardais

Entrepreneurs have been portrayed in paradoxically contrasting ways in the literature. On the one hand, they are said to be intrepid optimists who venture forth with great persistence even in the face of considerable uncertainty and multiple failures; on the other hand, they are held to be realists who are quick to acknowledge the negative realities of their initiatives and adapt very quickly. In order to reconcile these contrasting views, this study tracks in real time the frequent confidential communications of an entrepreneur and his closest consultant and partner during the last 6 months of a failing venture. We are able to gain insight into how by adopting a positive “frame” or consistent mindset about the future, the entrepreneur is able to sustain confidence in the face of significant challenge while at the same time acknowledging and reacting to significant problems in the present. We propose that an intrinsic quality of an entrepreneur is this ability to integrate or reconcile these seeming opposites—to manage paradox, largely by bifurcating time—by making temporal distinc-tions, and we show how that person simultaneously can be optimistic and realistic, and persistentandadaptive.

Introduction

Entrepreneurs are portrayed in divergent ways. First, they are said to be supreme optimists and paragons of hope (e.g., Brocas & Carrillo, 2004; De Meza & Southey, 1996). But they are also claimed to be hard-nosed realists capable of understanding the major threats that confront their enterprise on a daily basis (e.g., Liang & Dunn, 2008a, 2008b, 2010). A second contrast arises when entrepreneurs are said to be persistent bulldogs—fighting against challenges in a sustained way and struggling to save their venture even under dire circumstances (e.g., Sandri, Schade, Mußhoff, & Odening, 2010). At the same time, they are said to be flexible and adjust quickly (e.g., Brockhaus, 1982; Kuratko & Hodgetts, 2004). Can these opposing characterizations all be true?

One possible explanation for this seeming divergence in the literature is that research-ers have been examining different types or populations of entrepreneurs (Ucbasaran,

Please send correspondence to: Danny Miller, tel.: 514-340-6501, e-mail: danny.miller@hec.ca, and to Cyrille Sardais at cyrille.sardais@hec.ca.

P

T

E

&

1042-2587

Westhead, Wright, & Flores, 2010). Indeed, entrepreneurs can be a diverse group. But given the consistency with which findings for these opposing characteristics have emerged, that explanation may not account entirely for such divergence.

We believe that an important reason for these unreconciled and sometimes conflicting accounts of entrepreneurial tendencies is that too few studies have examined the actual thoughts of an individual entrepreneur over the course of his or her venture. Optimism, realism, persistence, and flexibility are best studied by examining the impressions and concerns of a particular person concerning different matters at many different points in time and at different stages of a venture. In the spirit of the “strategy as practice” literature (Carter, Clegg, & Kornberger, 2008; Whittington, 1996), our research tracked an entre-preneur’s real-time confidential communications with his closest consultant (one of the authors) during the last 6 months of an ultimately unsuccessful venture. The reflections of the consultant were also recorded.

The results from our study did supply clues as to why the very same entrepreneur might fit quite opposite descriptions, in a sense resolving the paradoxical demands of his business and of entrepreneurship in general (Lewis, 2000; Smith & Lewis, 2011). Our entrepreneur could be energetically optimistic and at the same time pragmatically realis-tic; stubbornly persistent—and also flexible. He distinguished sharply between the promise of future prospects for the business, and the challenges and real disappointments of the present. In effect,he bifurcated his worldview or “framing” of the venture accord-ing to time, thereby sustaining optimism in the face of a keen awareness of problems—a resolution not addressed by the current literature on paradox. Thus, although our entre-preneur made almost universally positive statements about the future of the business, these accompanied realistically negative statements about present conditions and challenges. Moreover, he persistently clung to a rosy frame of future prospects, but after acknowl-edging that there was little hope, he adjusted his thinking decisively.Only an accumula-tion of disastrous news dismantled his worldview—his frame—which then was adapted radically, not incrementally (Goffman, 1974). As we shall see, the findings from our consultant’s logs demonstrated a very different pattern of less persistence, less cohesion, and more piecemeal and gradual adjustment.

Our paper is structured as follows. First, we briefly describe the divergent charac-terizations of entrepreneurs and their contrasting orientations. We then outline the possi-bilities for a rapprochement via the management of paradox and describe our research method before presenting our results in the form of qualitative excerpts and quantitative analyses of our entrepreneur’s and consultant’s postings. We conclude with a discussion of the results using Goffman’s (1974) frame analysis as a means of interpretation and understanding.

Two Contradictory Portrayals of Entrepreneurs

Optimism Versus Realism

and act independently (Covin & Slevin, 1989; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Miller, 1983). Some scholars claim that entrepreneurs maintain their rosy optimism despite venture creation being a risky undertaking with a high risk of failure. In fact, they emphasize that serial entrepreneurs preserve their optimismeven after many of their own ventures have failed(Storey; Ucbasaran, Westhead, & Wright, 2006; Westhead & Wright, 1998; Wright, Robbie, & Ennew, 1997). Some entrepreneurs, given their optimism, are also said to be victims of hubris (Hayward et al., 2006). Certainly, there may be a functional reason for the optimism as it is unlikely that a pessimist would start a business given the uncertainties involved. Only optimism can sustain a person who must risk his or her capital, reputation, time, relationships, and status on what many might consider “a fool’s errand” (Busenitz & Barney, 1997).

Yet there is another facet to the entrepreneur as portrayed by a different literature. Some studies suggest that entrepreneurs are not overly optimistic, but in fact are risk averse, very realistic, and sometimes full of doubts (Xu & Ruef, 2004). Perhaps their past failures have made them that way (Collins & Moore, 1970; Kidder, 2011). Indeed, it has been argued that portfolio entrepreneurs—those who invest in multiple ventures at the same time, are hyper-realists who are quick to learn from their errors, and that that tendency tempers their optimism with a healthy dose of realism (Ucbasaran et al., 2010). Confirming accounts, particularly those within fine-grained corporate histories, show entrepreneurs as being hard-nosed realists who begin their ventures with a good deal of caution, avoid excessive risk taking, and understand better than most others the challenges confronting their venture (James, 2006; Landes, 2006).

A few studies have attempted to resolve the debate by examining different types of entrepreneurs, and finding, for example, that serial entrepreneurs are more optimistic than portfolio entrepreneurs (Storey, 2011; Ucbasaran et al., 2010). Moreover, optimism has been found to be more useful to entrepreneurs in stable rather than uncertain environments (Hmielski & Baron, 2006).

What remains unclear however iswhat exactly entrepreneurs are being optimistic and positive or realistic and negative about. Could it not be that the very same entrepreneur is both realisticandoptimistic—but about different things and at different times? Might that not make sense given that both optimism and realism are required to have any chance of success in a business venture (Liang & Dunn, 2008a, 2010)? Without optimism, who would dare to launch a new venture? Without realism, how could any venture possibly succeed?

Persistence Versus Adaptation

On the other hand, some scholars have characterized entrepreneurs as paragons of flexibility and decisive adaptation (Brockhaus, 1982). They change strategies and recognize new opportunities especially quickly (Dubini, 1989; Miller, 1983), move from initiative to initiative (Ucbasaran et al., 2006), and lead the way in innovation (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). Once more, there is a functional element to flexibility, as in any new business, conditions are constantly changing. No venture can be carried out without periodic adjustments both in perceptions and behavior. On the other hand, too much flexibility may give way to inconstancy of strategic vision, an inability to coalesce partners and stakeholders around a venture, and a squandering of the precious resources of a nascent business (Miller, 1990).

Allowing for inevitable and important individual differences among entrepreneurs, it is once again difficult to imagine many of them choosingbetween these two poles of persistence and adaptation. Too much persistence would guarantee extinction, particularly in an ever-changing environment such as that surrounding a new venture. Similarly, excessive adaptation would result in quitting a promising alternative too soon, and exhaust-ing firm assets on experiments not given enough of a chance to succeed. The question therefore is, how do some entrepreneurs balance persistence with adaptation, which aspects of their thinking change most or least readily, and when confronted with a dire situation, how quickly do they recognize that and alter their views of the viability of their venture? Again, given the demands of the job, it is hard to believe that entrepreneurs would be lacking in either of these qualities—but how do they reconcile or combine these seeming opposites?

Managing the Paradox

Is there some way an entrepreneur can manage the paradox of being both optimistic and realistic, both persistentandadaptive? The literature on the management of paradox holds promise in helping us to resolve these tensions (Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009; Bakhtin, 1981; Lewis, 2000). Paradox can be defined as “contradictory yet interrelated elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time” (Smith & Lewis, 2011, p. 382). It has been argued that managers confront numerous paradoxes at their jobs. They must exploit existing competencies to be efficient, but also must innovate. They must cut staff as the need requires but create cohesive corporate cultures. They must preserve complementarities among elements of strategy and structure but at the same time adapt to external changes (Poole & Van de Ven, 1989; Van de Ven & Poole, 1988). Most of the paradoxes discussed in the literature pertain to concrete practices: collaboration versus control (Sundaramurthy & Lewis, 2003), flexible versus efficient organization (Adler, Goldoftas, & Levine, 1999), exploration versus exploitation (Smith & Tushman, 2005), and even actively pursued goals such as profit versus social responsibility (Margolis & Walsh, 2003).

Unfortunately, the literature on paradoxes, although wide ranging, has concentrated on managers of mature companies, not entrepreneurs during the early stages of a venture. More importantly, it has focused on behavior more than mindsets and has never addressed the seemingly conflicting demands on entrepreneurs to be optimistic and realistic, as well as stubbornly persistent and boldly adaptive.

having a consistently positive mental frame of the future (Goffman, 1974). That simple expedient seems to contradict a vital theme in the paradox literature that it is extremely challenging for firms and managers to encompass and attend to paradoxical demands. This was by no means the case for our entrepreneur who was able to exhibit simultaneously both realism and optimism without apparent stress or difficulty. He also could shift very decisively from persistence to bold adaptation when the need arose.

In summary, our contribution not only surfaces two critical paradoxes unresolved in the entrepreneurship literature and unrecognized by the work on paradox, it also brings to bear a novel means of resolving these paradoxes.

The questions that guided this research are: do entrepreneurs embrace these seeming polarities of optimism/realism, and persistence/adaptation; do they attempt to reconcile these divergent modes; and if so, how do they accomplish that?

Our Approach

This research attempts to find what reconciliation may look like by studying the thoughts of an entrepreneur as he evolved in real time while he manages a new venture. Aldrich (2001, 2009) and Aldrich and Martinez (2001) have argued that the only useful way to study the behavior and thoughts of entrepreneurs is up close and over time. Scholars of strategy as practice (Johannisson, 2011; Whittington, 1996) have issued the same plea. In heeding these calls, we tried to get inside of the mind of the entrepreneur on an ongoing basis as he grappled with the challenges of a new venture—to see how he interpreted the different aspects of his business, and how those interpretations evolved. In fact, we believe that an important reason for the contrasting and largely unreconciled representations of the entrepreneur we have just presented is that accounts of entrepre-neurship and business creation tend to be retrospective.

Indeed, it is unfortunate that most of the literature on entrepreneurship is based on survey or case methods—often eliciting “after the fact” rationalizations that fail to reflect the uncertainties of the moment (Aldrich, 2001, 2009; Lamoreaux, 2001; Sardais, 2009a). Almost never do we have a “real time” account from the entrepreneurs themselves of their assessments of their venture and their core concernsas these evolveduring the first months of a new company. It is only with research having access to that kind of online longitudinal documentation that we may determine just what is going through the minds of some entrepreneurs as they create and manage their venture. We believe that the challenges facing entrepreneurs can be best understood only when we can determine their thoughts on an ongoing basis—specifically, the frameworks they appear to be using to understand their situation, and how those frameworks change as they oversee the first critical months of their business.

Our study builds on data that are new to the field. These come in the form of detailed and confidential diaries of two participants of a new venture in recreational tourism. They reflect impressionsat the time of writing, and demonstrate evolving pictures or “frames” of the situation of a business and the hopes of its principals.

Methods

Sample: The Firm and Parties Studied

recreational vehicle rentals, adventure tours, and sightseeing-by-air. Operations began in December 2010, and the firm employed up to 10 employees, with revenues reaching $100,000 per month. The firm never made a profit, and cash flow shortfall had reached $300,000 by the end of the period analysis, which extended from December 2010 until June 2011. (We have disguised genders and the exact nature of the business to preserve anonymity.) Our study focuses on two people. The first is a founder of the company who held the second largest ownership position. At the time of the firm’s founding, he had 15 years experience as an entrepreneur in building, turning around, and selling various businesses. He was in charge of operations, finance, and sales. As he was responsible for these crucial functions, a 20% owner, and the person with the most experience as an entrepreneur, he enjoyed virtually equal power with the CEO (the latter was a 40% owner with no previous entrepreneurial experience). The second party in the study was an investor and consultant to the company, and one of the current authors who is a tenured professor of management. Starting in January 2011, he worked for the firm 1 day per week. He served on the operating committee with both entrepreneurs who met regularly to monitor progress and discuss operating problems, opportunities, and strategy. The consultant had a degree in management and 4 years of consulting experience. He had known the entrepreneur for more than 5 years, and that relationship provoked the exchange of postings intended to gain insight into the firm and its challenges. The idea for the postings came from the entrepreneur, not the consultant. The former asked the latter if he would agree to respond to his e-mails regarding his feelings about the company. These exchanges at the time were

not intended for research purposes. Permission to use the material was only granted several months after both individuals had left the firm. It is the friendship and trust that existed between the parties that enabled us to access the reflections of our entrepreneur. We found it useful to be able to compare the observations of the founder with that of the potentially more objective consultant who was not an entrepreneur and had far less at stake financially and emotionally in the business.

Our study employed two distinct methodologies—the first qualitative, the second quantitative. We shall describe the qualitative methodology before addressing the quan-titative. In the Findings section, we follow the same sequence.

Qualitative Data and Analyses

Nature, Mode, and Frequency of the Narrative Data. The entrepreneur and the consult-ant wrote on a regular basis to reflect their thoughts about the firm, its problems and promise, its challenges, and its prospects. No constraints were proposed regarding what to write, except that the writing was to be done as frequently as possible to reflect ongoing thoughts concerning the business. The diaries were to be kept private and were in the form of e-mails between the two parties. They were written quickly—grammar and presenta-tion were of no concern. Currency and honesty were the major criteria. Over the 5.5 month period from 16th of February to 28th of July, 31 e-mail postings were written by the entrepreneur, and 35 by the consultant. Approximately 32 single-spaced pages of text were written by the entrepreneur (comprising 14,531 words), and about 49 pages by the consultant (25,665 words).

Quantitative Coding and Analyses

out by both authors, generated a list of all the administrative and functional categories of issues discussed across the narratives: issues in marketing and product development, operations, financing, human resources, general strategy, and administration. Each state-ment in each posting was coded according to which of these areas was addressed.

Then the two coders in double-blind fashion coded the subjects’ value judgments of the situation. Were the statements clearly positive, clearly negative, or unclear/neutral regarding their implications for the business? Coders coded 17 categories in all using three symbols:+for a positive evaluation that things were promising or going well;=for neutral

comments; and-for problems, difficulties, negatives, doubts, or poor outlook. In a third

stage of analysis, statements were also coded again by the two coders according to whether they related to present/past versus future conditions (the detailed coding results are available from the authors).

Data Reliability. As noted, two researchers were involved in the coding. One hundred percent of the entrepreneur’s posts and statements were coded by the consultant and a third party working double blind. Data consisted of 31 postings and 81 judgments about the business to be coded as positive, negative, or ambiguous: 74% of the ratings were identical between raters, in 23.5% of the cases, one rater assigned an “ambiguous” rating and the other a positive or negative one. In only 2.5% of the cases did one rater assign a positive and the other a negative rating. After reconciliation, each coder admitted that he had erred. In scoring the statements after the distinction was made between those con-cerning the present versus future, in 76% of the cases, there was perfect inter-rater agreement, in 16%, one rater scored “pastandpresent” and the other one of the two, and in 8% of the cases one rater coded “future” and the other “present.”

An additional rater with an MSc in management was recruited to assess the reliability of the consultant’s postings. Thirty-five postings and 120 statements were coded. For the positive versus negative postings, 79.5% of the ratings were identical between parties, in 16% of the cases one rater assigned an “ambiguous” rating and the other a positive or negative one. In 4.5% of the cases one rater assigned a positive rating and the other a negative one. For coding the distinction between statements concerning the present versus future, in 68% of the cases, there was perfect inter-rater agreement, in 23% one rater scored “past and present” and the other one of the two, and in 8% of the cases one rater coded “future” and the other “present.”

Findings

Table 1

Chronology of the Postings

Entrepreneur Consultant

Phase 1 Phase 1

Theme: The entrepreneur is mostly optimistic about present circumstances, but he shows a healthy dose of realism as he discusses present challenges in getting sales, suppliers, and even adequate management talent. By contrast, his statements about the future prospects of the business are almost entirely positive and optimistic. One can sense his enthusiasm from the texts.

Theme: Impressions of the entrepreneur and consultant are largely in sync regarding the present problems facing the

business—although the consultant is more detailed, negative, and fine grained in his opinions. Divergence is emerging between the two parties, however, regarding the future—the consultant has increasingly mixed opinions regarding the prospects for the business. And a critical memo follows the phase and marks its termination.

February 16

“Commercial development is not structured enough. We have many promising prospects and interests, but very few actual contracts.” March 9

“I’ve seen the planes [we will be renting]. They’re not great. If [the supplier] agrees to renew the seats, we could work with them. An older plane with very old seats can be OK for tourists looking for adventure, but not great for professional clients . . . [About an acquisition opportunity]. Here, it’s really interesting. The guy is 58 years old, and thinks that his company is worth almost nothing. But he has three key facilities we can use and all the permits we need.”

Realism regarding the present. Optimism concerning opportunity.

March 14

“I wonder if we haven’t paid four times its real worth for [Business Unit 1, which the firm had acquired]. even if on paper the valuation seemed reasonable at the time. We have under-estimated the following problems: The condition of the vehicles, which had cost us more than $20,000 to repair, an amount we wouldn’t have had to pay for new ones . . . The company had no system of management, no software or processes to manage orders, cash flow, clients, etc. In reality, with 17 vehicles, the company can only be profitable if it is managed by one person who will work like a dog during four months and hope to make enough revenue to pay for eight months of holidays.”

Realism regarding past mistakes and current challenges.

March 18

“The project is taking shape and I wake up earlier and earlier each morning, with the thrill of making it happen. . . . Today, we are going to fly the planes [in a trial], without knowing at this stage exactly where we are going to service and refuel them.”

Enthusiasm about the future. Concerns about some imminent practical aspects.

March 31

“Now, I do believe it. Wewillhave planes . . . starting from May. . . . I hope that we are going to be ready, because things are beginning to move fast and I feel that the business is on the verge of becoming much better that anything we had expected. However, nothing basically has changed, the facts are the same as yesterday, except that in two days, things will be ready for the airport and the planes, and as a result, everything we dreamed about is about to become a reality; and we are going to build on that.”

Hyper-optimism regarding future—realism about current limitations.

March 5

“We have to know whether we are selling dreams for the future, which we can do, or pointing to actual results; of course, we want to sell results but let’s be clear: we have only three things to sell [he goes on to list the assets]. Certainly, this company is not worth $10 million. But even if it’s worth $1.3 million, we would have created $1 million of value from six months of work . . .

“It’s good to write and observe, but much more exciting to participate in running the firm, to engage, with one’s heart, not only his brain.”

Realism regarding the value and meager assets of the firm. Excitement to be part of the adventure.

March 16h

“Curiously, this morning as I awoke, I was concerned about the business. It’s one of the first times. It’s ironic because it is happening probably only a few days or weeks before the clouds are starting to disappear, because it’s highly possible that within a month, because of the new clients and investors likely to be coming onstream, we could be in good shape for a long time to come.”

Optimism regarding the future but an undercurrent of doubt—a contrast with the more sanguine entrepreneur.

March 29

“I do think that these last days of March and early April are the most uncertain ones yet for this company. We are full of projects and prospects, but we have nothing concrete yet and no cash anymore.

“I have never been so close to telling myself: now, we are off on a long and promising trajectory, and at the same time saying, damn, I’m not sure whether we will still be alive not just in six months, but in a few days!”

Strange mixture of optimism and serious pessimism about future.

April 7

“What I would like, is for BU2, which was supposed to be the cash cow of this group, but until yesterday has produced no revenue, to start to produce some results!”

Table 1

Continued

Entrepreneur Consultant

Phase 2 Phase 2

The entrepreneur remains realistic about current problems and expresses frustration with his CEO. But the theme is still one of hope for the future.

The opening of this phase was the consultant’s April 17 memo: entitled “drowning.” There is an air of disappointment in how things are going and pessimism about the future. Clearly, a darker tone for the consultant than the entrepreneur. May 2

“BU3 is supposed to start operations in the coming weeks, but until now, nothing concrete has been accomplished. “Our credibility is seriously affected [by the CEO’s actions], and

it is very annoying.

“Anyway it’s a complete mess. I keep up the fight becauseall my ventures went through exactly such phases. But one really needs to have the faith to continue and be persistent.”

Realism about today’s problems—with an expression of hope and the necessity ineverynew venture to be persistent in the face of inevitable problems.

May 5

“I’ve just been to [a hotel] to renegotiate delaying payment. I didn’t think that I should go there after the CEO and say something different than he said, but I’ve followed [an investor’s] advice and went anyway. And it worked! We’ll pay them, when we get paid. Not before. From time to time, it’s good to be considered as a half-god, cleaning up another’s mess.”

A current victory—or opportunity.

May 13

“[The CEO] has convinced two travel agencies to distribute our products. . . . It’s cool. They are his friends. I wonder, why he didn’t call them before to induce them to sell our products. Most probably he considered that our operations were not ready yet. I hope that these guys will sell our products.”

Optimism about a new opportunity—with a critical note.

May 23

“Finally the CEO is visiting the travel agencies, something he should have done awhile ago. He seems to be in the process of lining up $800,000 of business for the coming year. Things are falling into place.

“My time horizon for this venture remains at one or two more years to full fruition, after which I will remain an investor not an employee.”

The project will pay off—eventually.

May 30

“I talked with X who mentioned that if we developed products for the Grand Prix, we could cash out big.”

Hope springs eternal.

April 17

Memo titled—“Drowning”

“If we go on, as we have, the business will soon die. It is necessary, if it’s not too late, to radically rethink our ‘suicidal’ strategy.

“In a plane that is going down, one’s instinct is always to pull the rudder the wrong way. In a small business, it’s the same thing. When things start to go bad because of a lack of funds—because sales aren’t coming in, the tendency is to increase the number of projects, as though the various chimeras being pursued are all beckoning to save the day . . . and bring in money. With Project X we are pursuing exactly what we should be avoiding (. . .)

“I have the feeling that we’re headed towards a brick wall. Is everything lost and only the crying to come? No—but we must act!”

A signal warning about very significant current problems, a strategy that is doomed to failure, and clouds on the horizon.

May 3

“I am hardly delighted by developments. Aside from X’s sales, we’ve had nothing in April. And the future remains uncertain. That notwithstanding, the past is over; lets take on the battles one at a time and work towards the future.”

Pessimism—but with resolve to act.

May 9

“Unbelievable—we fought for weeks to develop a business plan, which has brought in a paltry $25,000 investment. Now, all of a sudden, a third party is considering investing $500,000—the miracle the entrepreneur had been talking about these past weeks.”

Another mirage that will soon disappear.

May 30

“[The entrepreneur] gave me an update few days ago. Sales are ‘simmering’ very slowly. More precisely, more nibbles are coming in, so there’s some potential.

“But it’s becoming critical at this point, because [the lack of revenue] is what prevents us from acquiring investors. The project is good but without sales, things are extremely dicey. “In short, even if in the very short term, cash is the main

problem, as far as I’m concerned, we have above all a serious sales problem.”

Highlights of the Narrative

From the chronology, we see that the entrepreneur began with a good deal of opti-mism, while also recording negative posts regarding existing challenges and errors. If we take the first 19 postings—phases 1 and 2 inclusive—until 30th of May, the entrepreneur appears to be saying: “Although the business is beset with problems, this is normal for its stage of development, andthe future continues to be promising given the quality of the products and staff and the soundness of the concept of the business.” The entries of the postings all correspond more or less to such a view, and they do so persistently across the 19 missives. The 20th posting (6th of June) reflects a sea change in the attitudes of the entrepreneur and the beginning of phase 3. It was written after he had verified complaints regarding the poor quality of the services, and after it became clear that several

Table 1

Continued

Entrepreneur Consultant

Phase 3 Phase 3

The June 6 memo signals the beginning of this phase in which the entrepreneur finally turns negative about the future—and comes to mirror the views of the consultant.

June 5 represents “the last straw” for the consultant who feels he can no longer recommend the firm’s products to his friends.

June 6

“Something radical has to change. The cash flow is catastrophic, future sales prospects are more than uncertain. Of course, May is better than April . . .

“The current shareholders will be approached [for investment] but they will probably refuse to ante up more funds.Even I would refuse to do so. . . [The consultant] called me yesterday to talk to me about [his experience with the terrible service we offer]. I was furious without being totally surprised.”

Here, the entrepreneur begins to express real doubts about the future.

June 8

“If one day someone reads these emails, he will know, that I am totally de-motivated . . .

“And that’s why, normally, without this kind of moral contract with [the consultant] to write what I think day after day, I would never have written down such a thing. . . .

“But I feel like a fireman having to put out the fire . . . “I still believe in this project even if it was mishandled. So, I’m

not completely de-motivated. But I don’t really know where all this is going.”

The project is seen as having been mismanaged, even a waste of time, but there remains a glimmer of hope.

June 14

“I was a bit emotional, because I feel that the end of my adventure [in this company], at least as a salaried member, is reaching an end very quickly.”

The future looks bleak enough to consider leaving the firm. Then he writes almost nothing until later in July.

July 26

“I have now reached the point of turning the page on this business.”

June 5th

“Obviously, I have serious concerns about the production of the company. About the will of the staff to meet quality requirements. . . . And honestly, today,I feel I can no longer recommend our product, even to my friends.”

Shift for the consultant. It’s no longer “our” company but “theirs.” He doesn’t feel a part of it, and wants his friends to steer clear of it.

June 10th

“I think again about my talk with [the entrepreneur] at the end of April. I had said that we may have to fire most employees, to give up most projects, and only keep BU1. I am wondering why we mostly just continued as before.”

What had to be done has not been. It is probably too late now to save the company.

June 10

(Re. talks with another investor.) “We first talked about past losses and came to the conclusion that bankruptcy was inevitable. The $50,000 that the CEO could bring would only delay things for a month.”

There is no longer a sense of hope.

June 16

“BU2 was already dead, but we could have saved BU3 and above all BU1. Now, I’m convinced that everything is dead, it’s too late.”

Definitive statement about the future. “It’s over.” Then he writes almost nothing until later in July.

July 28

key staff members were not as competent as expected and a vital sales deal had fallen through. This posting is the first in which the entrepreneur realizes that even the future is no longer bright—that the road ahead will be filled with trouble.

The consultant also showed optimism about the future and realism about current issues at the beginning of the venture, but became wary about the prospects of the business more quickly than the entrepreneur. The entrepreneur also seemed much more optimistic about the future than the consultant, although he held similar views about the present. After the 12th posting (7th of April)—the end of phase 1, the consultant sensed that the accumulation of problems did not augur well.

In short, it appeared from the narratives (1) that the entrepreneur tended to be quite realistic about problems and challenges confronting the firm while at the same time remaining optimistic; (2) there was a good deal of consistency in the comments of both parties in the early stages of the venture, although the consultant was somewhat more realistic about the prospects from the beginning; (3) the consultant was quicker to become negative about the future of the business than the entrepreneur.

But how does our narrative help to resolve the paradoxes implicit in the entrepreneur-ship literature: between optimism and realism, and persistence and adaptation? We shall revisit our data to address these paradoxes in turn, in each case examining first the qualitative information and then verifying our impressions quantitatively using the totality of the coded data.

Optimism Versus Realism

Qualitative Findings. Table 1 makes clear that the entrepreneur is boldly optimistic about the future. He uses phrases such as “the expected sales volume is so massive that it gives us, all of a sudden, a major negotiating advantage”; and “everything is still very tentative but at the same time, things are falling into place,” and “I feel that the business is on the verge of becoming much better than anything we had expected.” Even when things looked bleak he says “but everyday we send out quotes and that is an additional reason to be hopeful.”

At about the same time the entrepreneur made these statements, typically in the very same memo, he admits of the current challenges confronting the business. “I’ve seen the planes and they’re not great . . . not great for professional clients,” “We have under-estimated the following problems: The [poor] condition of the vehicles, the company has no system of management, no software or processes to handle orders.” “Our credibility is seriously affected by the CEO’s actions,” “Anyway [business unit 3] is a complete mess. I keep up the fight because all my ventures went through exactly such phases.”

The consultant’s narratives were more measured: the current problems listed were presented in even greater detail than was true for the entrepreneur, and the expressions of hope for the future were more restrained.

In short, it appeared that our entrepreneur, and to a lesser degree the consultant, were able to be both optimistic and realistic at the same time. The optimism pertained to the future, and the realism related to current problems and events. We wished to confirm this observation more systematically and in a quantitative manner by taking into accountallof our narrative data.

and very strongly negative in phase 3 (77%).1That this optimism, and later pessimism or

realism, was spread across so many variables, functions, and product lines during a given phase does suggest that there was an orchestrating and filtering lens through which the entrepreneur viewed the future. At first, everything regarding the future seemed bright. It is as though the appraisal of individual elements of the business were “rose colored” by an essentially positive frame. The same consistency across elements—this time negative—also materialized in phase 3.

1. As shown by Table 2, no clear pattern surfacedbeforebifurcating the data according to statements about current versus future conditions. Only with temporal bifurcation did a clear contrast emerge.

Table 2

Number of Positive and Negative Statements for Entrepreneur and Consultant for Each Phase Regarding Present and Future of the Business

Entrepreneur Consultant

Clearly positive Clearly negative Clearly positive Clearly negative

Total 26% 58% 23% 61%

Phase I 57% 24% 48% 39%

Phase II 30% 52% 23% 52%

Phase III 0% 88% 0% 98%

ALL present 8% 75% 15% 76%

Phase I present 11% 44% 8% 77%

Phase II present 13% 71% 27% 65%

Phase III present 0% 95% 0% 100%

ALL future 53% 32% 29% 51%

Phase I future 92% 8% 65% 23%

Phase II future 78% 0% 19% 39%

Phase III future 0% 77% 0% 95%

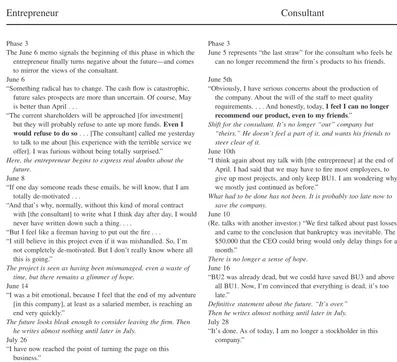

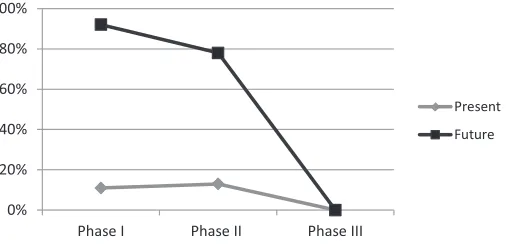

Figure 1

Favorable Statements About the Future: Entrepreneur Versus Consultant

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Phase I Phase II Phase III

Entrepreneur

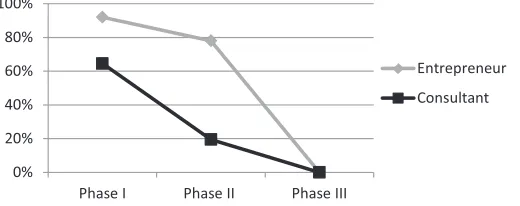

This optimism of the early phases did not pertain to statements about the present

(see Figure 2). The entrepreneur fully recognized the current problems facing the busi-ness (only 11% or 12% of his statements were positive during the first two phases)— which suggests a negative evaluation of current conditions, especially during phase 2. That the view of the future could remain so bright given the realism about the present confirms the strength of the optimism. In a sense, for the entrepreneur the future reflects a positive worldview since it is maintained despite the negatives expressed in current appraisals.

It is instructive that the positive to negative percent statistics (for the three phases combined) regarding the present are similar between the entrepreneur and the consultant—8%/75% for the entrepreneur versus 15%/76% for the consultant. By con-trast, statements regardingthe futureare strikingly different: 53%/32% for the entrepre-neur versus 29%/48% for the consultant. These ratios differed at the .01 level under Fisher’s exact test. In short, if we use the consultant as a rough analytical standard of objectivity, it appears that the entrepreneur is quite realistic in recognizing the challenges and problems facing his business in the present. But he is far more optimistic than the consultant about the future.

Persistence Versus Adaptation

Qualitative Findings. Our chronology of the postings began to show important diver-gences between the entrepreneur and the consultant in the second phase of the narrative. It became clear that the entrepreneur was more positive about the future than the consult-ant who was far more wavering or inconsistent in his evaluations. In other words, the entrepreneur was more persistent in his optimism regarding the future. As late as May when the venture was struggling with severe operating, marketing, and financial prob-lems, the entrepreneur said “one really needs to have faith to continue and be persistent” as he pointed to himself as “a half-god, cleaning up another’s mess.” He also rationalized the difficulties as “normal among new ventures.” By contrast, by May, and even before, theconsultantwrites “I do think that these last days of March and early April are the most uncertain ones yet for this company. . . . I’m not sure whether we will still be alive not just in six months but in a few days.”

Figure 2

Favorable Statements About the Present: Entrepreneur Versus Consultant

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Phase I Phase II Phase III

Entrepreneur

However, once the entrepreneur sensed that the business had little chance of succeed-ing in the marketplace, his reaction was not reluctant acquiescence but a very decisive decision to recognize losses, quit the venture, and move on to the next challenge. On June 14 he states, “I feel that the end of my adventure [in the company], at least as a salaried member, is coming to an end very quickly [he is already preparing to leave for greener pastures].” Then on July 26, long before the business (which still “survives”) almost goes bankrupt, the entrepreneur states, “I have now reached the point of turning the page on this business.” Ultimately, his positive frame is abandoned.

In short, the qualitative findings seem to suggest that the entrepreneur is more persistent than the consultant in embracing a positive frame of the future for the business; but once he believes things have become hopeless, he changes and adapts his view dramatically and is ready to go. He is both persistent and then decisively negative, but at different times. By contrast, the consultant even early on is quicker than the entrepreneur to be more reserved and nuanced in his statements about the future of the business, and then even when he is pessimistic in the second phase, continues to express hope about the future—displaying a far more mixed set of reflections.

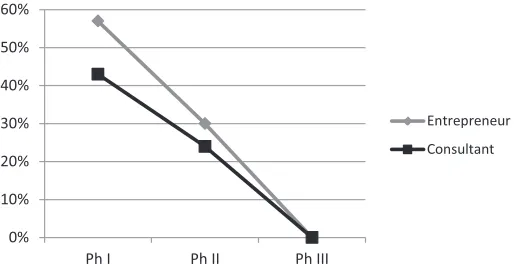

Quantitative Findings. Again, we wished to establish whether these observations of persistence and subsequent decisive adaptation would be borne out by a more systematic treatment of the complete set of narrative data. The entrepreneur remained more positive than the consultant about the future of the business in both the first and especially the second phase of the venture. Our data indicate that the entrepreneur is persistent in adhering to his positive frame of the future throughout the 19 postings—long after the consultant has begun to express doubts about the firm’s prospects. Then he suddenly changes his opinion in a dramatic and wholesale way.

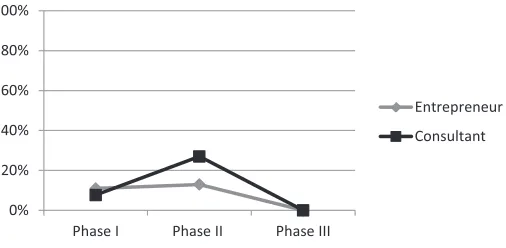

Whereas the data aggregating statements about the present and future showed a gradual decrease in positives (Figure 3), that was not true for statements aboutthe future, where the evolution across the phases went from 92% positive to 78%, to 0% in the third phase, while negative statements rose from 8% to 13% to 77% (see Table 2 and Figure 4). Clearly, the frame of the entrepreneur changed radically at the end of the second phase. Moreover, the frame shift represented the entrepreneur’s suddenly altered view of the future. By contrast, the progression of statements regardingthe present, which were more nuanced

Figure 3

Favorable Statements (Present and Future): Entrepreneur Versus Consultant

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60%

Ph I Ph II Ph III

from the beginning, was far more gradual: with negative statements increasing across the phases from 44% to 71% to 95% and positives moving from 11% to 13% to 0%.

Figure 1 shows that whereas the entrepreneur is only slightly more optimistic about the future than the consultant during the first phase, that gap widens considerably in the second phase—with the consultant’s positive statements approaching 0 and the more persistent entrepreneur maintaining a positive outlook. The third phase then shows how the consultant declines somewhat gradually toward 0 positives, whereas the entrepreneur shows a dramatically adaptive quantum drop—never to look back. More precisely, during phase 2, positive statements regardingthe futurefor the consultant fell to 20% while they remained at 78% for the entrepreneur (the difference is significant at beyond the .01 level under Fisher’s exact test). Also, for the consultant the proportion of “unclear” statements rises steeply in phase 2 (from 13% to 43%, significant at the .01 level), while positive statements drop sharply.In short, the entrepreneur’s frame shows more inertia than that of the consultant despite the two individuals rendering parallel evaluations of the current situation facing the firm.

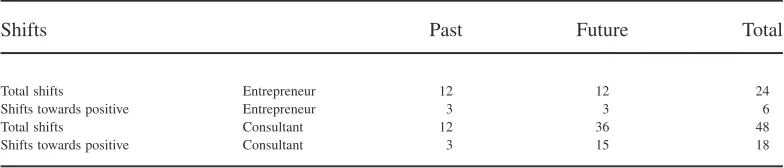

Such inertia could also be detected in the way the entrepreneur and the consultant changed their opinions within a category. For example, the consultant has twice as many statements as the entrepreneur, but three times as many shifts of opinion regarding the future (36 versus 12). More importantly, if we look only at the positive shifts of opinion about the future, the consultant has five times as many as the entrepreneur (15 versus 3). This suggests that our entrepreneur rarely reversed himself once he changed his mind. The situation is very different for statements about the present where there are a similar number of positive and negative changes of opinions between the two parties (Table 3).

The Frames of the Entrepreneur

As noted, the entrepreneur embraced a positive frame of the business—enabling him to acknowledge present realities while sustaining optimism about the future. In the end, it was possible to identify two frames of mind or worldviews of our entrepreneur that might be characterized as follows:

Frame A: We’ve got a fantastic project, a solid team, and some excellent product offerings. Our financial situation and our sales at the moment are certainly a problem,

Figure 4

Entrepreneur’s Favorable Statements: Present Versus Future

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Phase I Phase II Phase III

but with our project’s potential and our management team, the outlook is bright and our sales and finances will improve in due course.

Frame B: In actual fact, our outlook is very poor. It is not at all evident that sales will improve, and our financial situation is not only critical, but the ways of resolving the situation are by no means apparent. Moreover, in reality, our products are far from being as good as we had assumed and the capabilities of the CEO and his team are lacking.

Frame A applies to the beginning of the period of analysis and frame B to the last part. In the interim, from the consultant’s posting, we sense a hesitation between these two frames. For postings of the entrepreneur, although we can perceive some increasing doubts, frame A continues even once the consultant has entered a pessimistic phase (see our later discussion). Again, the entrepreneur’s optimistic frame seemed to sustain his belief in the business, allowing him to be at once realistic about current conditions and hopeful about the future. It helped him to resolve these divergent attitudes—to reconcile the paradoxical tension between optimism and realism. It also supported his persistence in the face of adversity.

Discussion

A Different Lens on Paradox

As noted, the literature on organizational paradox is extensive. But it has focused on managers, not entrepreneurs, it has concentrated on paradoxes of actions, behavior, and goals, and it has dealt mostly with resolutions via spatial separation, tolerance of ambiguity and conflict, mixed messages in discourse, sequential attention to goals, and alternating time horizons for particular goals and decisions (Poole & Van de Ven, 1989; Smith & Lewis, 2011). Our analysis has taken a different tack and produced different insights. First, it deals with entrepreneurs in a new venture, not managers in an established organization. The former are tasked, sometimes on an ongoing basis, with sustaining optimism in the face of challenging realities, while at the same time having to grapple with those realities, and persisting while being ready to adapt dramatically. Those paradoxes have been ignored. Perhaps most importantly, this research has surfaced a way of resolv-ing paradox that seems less demandresolv-ing than the approaches discussed in the literature. By bifurcating time frames, managers might be able to better appreciate, for example, the apparent contradictions between exploration and exploitation, crisis and opportunity, and opposing stakeholder demands. They can acknowledge current difficulty while preserving

Table 3

Shifts Between Positive and Negative Evaluations

Shifts Past Future Total

Total shifts Entrepreneur 12 12 24

Shifts towards positive Entrepreneur 3 3 6

Total shifts Consultant 12 36 48

positive vision, pursue exploitation while considering opportunities for exploration; reward clients today in the service of owners tomorrow. Scholars of entrepreneurship and of paradox would be wise to explore further this temporal reconciliation of conflicting demands.

Paradoxes, Dualities, and Frames

Our findings suggest that our entrepreneur appeared to be capable of embracing duality—he was not optimisticorrealistic—he was both; he was not persistent or flexible, again he was both. The challenges confronting an entrepreneur require him or her to cope with this seeming paradox of opposites at least much of the time (Fraser & Greene, 2006; Lewis, 2000; Smith & Lewis, 2011). Entrepreneurs require optimism to buoy them during times of uncertainty and as they cope with liabilities of newness—yet they must be realistic to avoid being damaged by a stark reality. Also, they must be persistent—they cannot retreat with each reversal of fortune; yet they must be flexible enough to react decisively. Our entrepreneur employed two interconnected devices to reconcile these paradoxical demands: bifurcating the world according to time, and utilizing a positive frame about the future to sustain that bifurcation. He could be optimistic about the future and realistic about the present; and thus be persistent during periods of challenge—and ultimately willing to change decisively.

According to Erving Goffman (1974), frames are internally consistent pictures or scenarios that people use to make sense of their world—their view of “what is going on here.” They represent a personal construction of reality that creates meaning out of a chaotic set of stimuli. They mold how current events and facts are interpreted and weighed to enable us to form a coherent picture of a situation. Goffman maintains that individuals may be mistaken in the frames they adopt. And as these frames form coherent gestalts, when they change, they move from one picture to another that is different and tells quite a different story. In most cases, the new information is rendered consistent with what is already there (Miller & Sardais, 2013).

Our entrepreneur’s frame of the future was solidly optimistic and sustained his persistence even though he was aware of challenges in the present. Thus, the postings of our entrepreneur illustrated a particular interpretation, in this case an optimistic one, along many pieces of information over an extended period of time. This frame-like quality was attested to by consistency in how very different elements of information all were inter-preted positively, and in the durability of this positive view of the world, even in face of important disconfirming information.2 Only when challenges became so dire as to

destroy the frame—a process that took time given the thematic and coherent nature of that frame—did a new more negative frame replace it, one representing a different set of beliefs and expectations that ultimately propelled decisive abortive action. Indeed, it might be said that the word optimism oftenimpliesa frame as it generally covers multiple aspects of reality and exhibits significant stability and an overriding theme or structure.

The importance of the frame was twofold: it instilled an internal coherency that guided how the entrepreneur interpreted his world.It at first sustained his confidence even

while he witnessed current problems. However, the frame also encompassed expectations such that when enough of them were defeated, a dramatically different conception of reality was needed. We explore these ideas in detail below.

How Optimism and Realism Are Reconciled. Given the many challenges facing a nascent enterprise, entrepreneurs must combine hope with realism. They must be confi-dent, optimistic, tolerant of uncertainty, and persistent in the face of challenge: in short, they must be hopeful and act upon that hope. And the sagas of successful entrepreneurs reveal these qualities in abundance (Collins & Moore, 1970; Shapiro, 1975). At the same time, entrepreneurs must be absolutely cognizant of the challenges and obstacles to success confronting their venture. They must be realistic and admit the problems that exist (Kidder, 2011). Otherwise they are doomed to rapid failure.

The juxtaposition of a positive frame for the future accompanied by a rather realistic and nuanced rendering of the present allowed our entrepreneur to encompass these paradoxical dualities of optimism and realism (Cooper et al., 1988; Fraser & Greene, 2006; Hayward et al., 2006; versus Ucbarasan et al., 2010; Xu & Ruef, 2004). The positive frame sustained hope in the face of recognized challenge.

How Persistence and Adaptation Are Reconciled. The entrepreneur’s frame also remained quite stable—he was persistent. His positive framing of the future remains in place even as conceptions of the present darken. But he changed very decisively under dire circumstances. His pattern of change was that of punctuated equilibrium—stability punc-tuated by decisive reorientation (Miller & Friesen, 1984; Tushman & Romanelli, 1985). First, there is delay—and then a veritable explosion of negative evaluations. A significant event triggered a rapid and complete change in judgment about the prospects of the company. Here, we have the resolution of the second paradox—persistence followed by adaptation (cf. Gatewood et al., 1995; Shaver & Scott, 2002; Wu et al., 2007; versus Brockhaus, 1982; Dubini, 1989; Stamm, Thurik, & Zwann, 2010). Entrepreneurs indeed may be persistent—their positive frames enable them to be so. At the same time, they respond decisively when bright prospects appear no longer to be tenable.3

Thus, Goffman’s (1974) notion of frames helps to explain change at the level of the individual decision maker. The cohesiveness and consistency of the entrepreneur’s frame makes it resistant to change—and stabilizes it until truly trying conditions move him to radically reconfigure his perceptions and adopt a new frame. By contrast, the more tentative and nuanced approach of the consultant enables him to entertain multiple frames, and thereby move more readily from a positive to a negative view of the enterprise.

There may be several reasons for the stable positive frame of the entrepreneur. He had a lot at stake in the venture: money, pride, relationships, reputation, and self-efficacy. It was hard to place those things in jeopardy by “admitting defeat.” Also, entrepreneurs are, by their nature, more optimistic than analysts and consultants (Collins & Moore, 1970; Kuratko et al., 1997). The former haveto be optimistic to embark upon their uncertain ventures; the latter must be critical to serve as useful advisors.

An Advantage of Inertia? An advantage of inertia for small, new companies relates to the level of uncertainty, which is extremely high (Stinchcombe, 1987). Typically, things are in

a state of flux while the business is trying to establish itself on a stable footing. Constant adaptations to that uncertainty would bleed the firm of resources and make for an orientation that is so inconsistent that a business could not orchestrate an effective strategy or learn systematically about its strengths (Miller & Friesen, 1984). Only inertia on the part of the entrepreneur about his vision for the future can sustain and stabilize the firm’s trajectory of development.

Entrepreneurs are founders of businesses, and thus subject to all of the liabilities of newness. These involve a lack of capital, untried routines, a paucity of managerial talent, an underdeveloped or unfamiliar market, and powerful competitors (Stinchcombe, 1987). Only persistence in the face of these challenges can sustain the entrepreneur and create the stability needed during the founding phases of an enterprise.

This last point is especially interesting as entrepreneurs are expected to be among the least inertial of people—innovative, flexible, adventurous (Covin & Slevin, 1989; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). And yet, in our study, the consultant was quicker to change and be influenced by current developments in the business than the entrepreneur. Certainly, entrepreneurs have been characterized correctly as people of action—as doers rather than thinkers—and agents of change (Kirzner, 1979). But clearly there is a difference between changing things in one’s organization and vacillating in one’s convictions about an organization’s fate. One might argue that inertial convictions arerequiredof bold agents of change. Undecided people with few convictions may change their minds frequently, and thus rarely have the resolve to act boldly (Kuratko et al., 1997). In short, the field of entrepreneurship would do well to pay more attention to the occasional advantages of certain types of inertia in venture creation, and to study also the downside of flexibility in conviction.

A Word on Method

One of the most important aspects of this study is its method. The only way we could gain insight into how our entrepreneur was able to encompass the paradoxical demands of his job was to monitor his thinking on a regular basis as his thoughts occurred and as he handled the different events in his business life. This required an approach akin to that recommended by scholars of “strategy as practice” (Whittington, 1996) and “sense-making” (Weick, 2012). Specifically, it required that we get inside the mind of the entrepreneur on a regular basis and in a setting where the most frank and private com-munication with a confidant was possible. This confidence between subject and researcher was vital. So was the openness of the topics that the subject could discuss. Our entre-preneur had all aspects of the business to think about, and it was necessary that he be encouraged to talk (write) about whatever he was concerned with at the time (how else could we have discovered the important distinction between future and current issues). Finally, the longitudinal nature of the study and the frequency of writing were critical. Our entrepreneur changed his views a great deal during the study—it was only by viewing his behavior over time that we could document the evolution in his levels of persistence, adaptiveness, and optimism. We believe that the study of entrepreneurship can be mightily enhanced were such methods to be used more commonly, methods elaborated by Uy, Foo, and Aguinas (2010).

question of what is the most relevant time horizon for studying different types of man-agement phenomena is an important one, and it has been broached by numerous management researchers (Bluedorn, 2002; Bluedorn & Denhardt, 1988; Butler, 1995; Orlikowski & Yates, 2002; Whipp, Adam, & Sabelis, 2002). Subsequent studies of entrepreneurship would do well to employ that work in determining the relevant time horizons for studying different types of entrepreneurial decisions at different stages of the firm life cycle.

Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Although this study represents a rare instance in which it was possible to access frank, often personal reflections from an entrepreneur on an ongoing basis, we can never be sure that all of the important thoughts of that individual were captured. Our subject was pressed for time. Indeed, during periods of crisis, which are in many ways the most interesting, time pressures could be enormous. Thus, we may have missed some key reflections. Moreover, entrepreneurs are people of action (Johannisson, 2011). They act first and reflect later. So there is a danger that reflections cover only some aspects of reality. Fortunately, because postings were written in real time, there was less risk of ex-post

rationalization; and because postings were confidential there was no incentive for self-justification. Another limitation of the analysis is that we were able to study only a single entrepreneur, and the venture we examined was a failure.

More important, the act of penning a posting may have influenced some of the events being described. The entrepreneur’s taking time to think and write about his feelings, hopes, and concerns may have altered how he handled various events. Moreover, the mirror offered by the consultant—one demanded by the entrepreneur—also might have changed the course of events. Needless to say, in any form of proximate research, it is impossible to observe without influencing the object of observation.

Our findings suggest lessons for further research. First, when studying entrepreneur-ship it can be revealing to monitor the thoughts of an entrepreneur while he or she is in the process of building a business, and where the subject has to confront the uncertainty of the situation (Lamoreaux, 2001; Sardais, 2009b). It is also useful to track a broad set of categories of behavior to allow for the characterization of a rich frame, and to distinguish statements about the future versus the present, as these may be divergent. Establishing a nonentrepreneurial baseline as we did for our consultant might also be helpful. Such real time, fine-grained exploration may dispel some of the entrepreneurial caricatures to be found in the popular literature.

To advance theory, future researchers might wish to use Goffman’s (1974) concept of frame to better capture what goes on in the mind of a decision maker and to discern the sources of inertia—and of change (Begley & Boyd, 1987). Frame analysis also can be used to understand why some entrepreneurs are characterized as optimistic and others as grounded realists (Liang & Dunn, 2008a, 2008b, 2010). Indeed, it might force scholars of entrepreneurship to make more careful distinctions between past and present consider-ations and examine the evolution of their frames over time.

REFERENCES

Adler, P.S., Goldoftas, B., & Levine, E. (1999). Flexibility vs. efficiency? A case study of model changeovers in the Toyota Product System.Organization Science,10, 43–68.

Aldrich, H.E. (2001). Who wants to be an evolutionary theorist.Journal of Management Inquiry, 10(2), 115–127.

Aldrich, H.E. (2009). Lost in space, out of time: Why and how we should study organizations comparatively.

Research in the Sociology of Organizations,26, 21–44.

Aldrich, H.E. & Martinez, M.A. (2001). Many are called, but few are chosen: An evolutionary perspective for the study of entrepreneurship.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,25(4), 41–56.

Andriopoulos, C. & Lewis, M.W. (2009). Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation.Organization Science,20(4), 696–717.

Bakhtin, M. (1981). Discourse in the novel. In M. Bakhtin & M. Holmquist (Eds.),The dialogic imagination

(C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.) (pp. 269–422). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Begley, T. & Boyd, D. (1987). Psychological characteristics associated with performance in entrepreneurial firms and small businesses.Journal of Business Venturing,2(1), 79–93.

Bluedorn, A. (2002).The human organization of time: Temporal realities and experience. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Business Books.

Bluedorn, A.C. & Denhardt, R.B. (1988). Time and organizations.Journal of Management,14(2), 299–320.

Braybrooke, D. & Lindblom, C. (1963).A strategy of decision. New York: Wiley.

Brocas, I. & Carrillo, J. (2004). Entrepreneurial boldness and excessive investment.Journal of Economics and Management Strategy,13(2), 321–350.

Brockhaus, R.H. (1982). The psychology of the entrepreneur. In C.A. Kent, D.L. Sexton, & K.H. Vespers (Eds.),Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship(pp. 39–71). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Busenitz, L. & Barney, J. (1997). Differences between entrepreneurs and managers in large organizations: Biases and heuristics in strategic decision-making.Journal of Business Venturing,12(1), 9–30.

Butler, R. (1995). Time in organizations.Organization Studies,16, 925–950.

Carter, C., Clegg, S., & Kornberger, M. (2008). Strategy as practice.Strategic Organization,6.1, 83–99.

Collins, O. & Moore, D. (1970).The organization makers. New York: Appleton, Century, Crofts.

Cooper, A., Woo, C., & Dunkelberg, W. (1988). Entrepreneurs’ perceived chances for success.Journal of Business Venturing,3(1), 97–108.

Covin, J.G. & Slevin, D. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments.

Strategic Management Journal,10(1), 75–88.

Cringely, R.X. (2000).Accidental empires. New York: Harper.

De Meza, D. & Southey, C. (1996). The borrower’s curse: Optimism, finance and entrepreneurship. The Economic Journal,106, 376–386.

Erikson, T. (2002). Entrepreneurial capital: The emerging venture’s most important asset and competitive advantage.Journal of Business Venturing,17(3), 275–290.

Fraser, S. & Greene, F.J. (2006). The effects of experience on entrepreneurial optimism and uncertainty.

Economica,73, 169–192.

Gatewood, E.J., Shaver, K., & Gartner, W. (1995). A longitudinal study of cognitive factors influencing start-up behaviors and success at venture creation.Journal of Business Venturing,10, 371–391.

Goffman, E. (1974).Frame analysis. Boston: Harvard.

Hayward, M.L., Shepherd, D.A., & Griffin, D. (2006). A hubris theory of entrepreneurship.Management Science,52(2), 160–172.

Hitt, M.A., Ireland, R.D., Camp, S.M., & Sexton, D.L. (2002).Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating a new mindset. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hmielski, K. & Baron, R. (2006). Optimism and environmental uncertainty: Implications for entrepreneurial performance.Babson Kauffman Entrepreneurship Research Conference Paper.

Jackson, T., Weiss, K., Lundquist, J., & Soderlind, A. (2002). Perceptions of goal-directed activities of optimists and pessimists.Journal of Psychology,136(5), 521–532.

James, H.S. (2006).Family capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Belknap-Harvard University Press.

Johannisson, B. (2011). Toward a practice theory of entrepreneuring.Small Business Economics,36, 135–150.

Kidder, T. (2011).The soul of a new machine. Boston: Little-Brown.

Kirzner, I.M. (1979).Perception, opportunity, and profit: Studies in the theory of entrepreneurship. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kuratko, D. & Hodgetts, R. (2004).Entrepreneurship(5th ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western.

Kuratko, D., Hornsby, J., & Naffziger, D. (1997). An examination of owner’s goals in sustaining entrepre-neurship.Journal of Small Business Management,35, 24–33.

Lamoreaux, N. (2001). Reframing the past: Thoughts about business leadership and decision making under uncertainty.Enterprise and Society,2(4), 632–669.

Landes, D.S. (2006).Dynasty. New York: Viking.

Lewis, M. (2000). Exloring paradox: Towards a more comprehensive guide.Academy of Management Review,

25, 760–776.

Liang, K. & Dunn, J. (2008a). Are entrepreneurs optimistic, realistic, both or fuzzy?Academy of Entrepre-neurship,14(1 & 2), 51–76.

Liang, K. & Dunn, P. (2008b). Exploring the myths of optimism and realism in entrepreneurship related to expectations and outcomes.Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship,20(1), 1–17.

Liang, K. & Dunn, P. (2010). Entrepreneurial characteristics, optimism, pessimism, and realism.Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship,22(1), 1–22.

Lovallo, D. & Kahneman, D. (2000). Living with uncertainty.Journal of Behavioral Decision Making,13, 179–190.

Margolis, J.D. & Walsh, J. (2003). Misery loves company: Rethinking social initiatives by business. Admin-istrative Science Quarterly,48, 268–305.

Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms.Management Science, 29(7), 770–792.

Miller, D. (1990).The Icarus paradox. New York: HarperBusiness.

Miller, D. & Friesen, P. (1984).Organizations: A quantum view. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Miller, D. & Sardais, C. (2013). How our frames direct us: A poker experiment. Organization Studies, doi:10.1177/0170840612470231

Orlikowski, W.J. & Yates, J. (2002). It’s about time: Temporal structuring in organizations. Organization Science,13(6), 684–700.

Poole, M. & Van de Ven, A. (1989). Using paradox to build management and organization theories.Academy of Management Review,14(4), 562–578.

Puri, M. & Robinson, D.T. (2004). Optimism and economic choice.Journal of Financial Economics,86(1), 71–92.

Sandri, S., Schade, C., Mußhoff, O., & Odening, M. (2010). Holding on for too long? An experimental study on inertia in entrepreneurs’ and non-entrepreneurs’ disinvestment choices.Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization,76(1), 30–44.

Sardais, C. (2009a). Mêmes causes, mêmes effets?Management International,13(3), 47–73.

Sardais, C. (2009b).Patron de Renault. Pierre Lefaucheux (1944–1955). Paris: Les Presses de Sciences-Po.

Shapiro, A. (1975). The displaced, uncomfortable entrepreneur.Psychology Today,11(7), 83–89.

Shaver, K.G. & Scott, L.R. (2002). Person, process, choice. Entrepreneurship: Critical Perspectives on Business and Management,2(2), 334–350.

Smith, M. & Lewis, M. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381–403.

Smith, W.K. & Tushman, M.L. (2005). Managing strategic contradictions: A top management model for managing innovation streams.Organization Science,16, 522–536.

Stamm, E., Thurik, R., & Zwann, P. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit in real and imagined markets.Industrial and Corporate Change,19(4), 1109–1139.

Stinchcombe, A. (1987).Constructing social theories. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Storey, D.J. (2011). Optimism and chance: The elephants in the entrepreneurship room.International Small Business Journal,29(4), 303–321.

Sundaramurthy, C. & Lewis, M. (2003). Control and collaboration: Paradoxes of governance.Academy of Management Review,28, 397–415.

Tushman, M. & Romanelli, E. (1985). Organizational evolution.Research in Organizational Behavior,7, 171–222.

Ucbasaran, D., Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (2006).Habitual entrepreneurs. Aldershot, UK: Edward Elgar.