Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 00:24

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

The Need for Continuing Education on Rapidly

Changing Business Issues: Internet Privacy as a

Telling Example

Carl S. Bozman & Kathy L. Pettit-o'malley

To cite this article: Carl S. Bozman & Kathy L. Pettit-o'malley (2002) The Need for Continuing Education on Rapidly Changing Business Issues: Internet Privacy as a Telling Example, Journal of Education for Business, 77:4, 219-225, DOI: 10.1080/08832320209599075

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599075

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 14

View related articles

The Need for Continuing Education

on Rapidly Changing

Business Issues: Internet Privacy

as aTelling Example

CARL S. BOZMAN

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Gonzaga University

Spokane, Washington nternet privacy issues occur acrossI

business functional areas and may inhibit the success of any organization engaged in exchange activities. Trust in the rapidly evolving electronic market- place is a critical component in the via- bility of firms that rely on Internet fea- tures to create value. For example, consumer surveys indicate that a signif- icant number of people either refuse to go online or are limiting their online activities because of a perceived lack of privacy (Green, 1998; Lenhart, 2000). In addition, frequent Internet users are prone to provide false information or subvert data-gathering attempts alto- gether because they lack confidence in Web site privacy (Fox, 2000; “Privacy and American Business,” 1997).Consumer concerns regarding Inter- net privacy are not without merit. Infor- mation technology has created an unprecedented revolution in the ability to systematically acquire and dissemi-

nate consumer data (Blattberg, Glazer,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Little, 1994). Individual consumptionbehavior can be easily tracked, profiled, and shared among diverse users. People are becoming increasingly aware that they lack any measure of anonymity in Web-based activities (Horrigan, 2000).

It is not too surprising, then, that any

ABSTRACT. Business educators often must teach topics that are chang-

ing rapidly or that extend well beyond

their specialty training. Thus, it is crit-

ical that faculty perceptions of knowl- edge correspond with objective mea-

sures of faculty knowledge. In this study, the authors examined the con-

sistency between faculty members’ perceived and actual knowledge about a specialty topic in a rapidly evolving area: Internet privacy. The authors also

investigated faculty perceptions regarding the importance of different dimensions of Internet privacy. Their

results suggest that, although some important issues are being addressed adequately, others are being over- looked because of a lack of accurate information and faculty preparation

and training.

discussion of Internet privacy often results in calls for government regula- tion. These requests are being made more frequently and forcefully. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has, in particular, identified Internet privacy as a major issue that must be addressed on a priority basis (Federal Trade Com- mission, 199813; Miyazaki & Fernandez, 2000). In the past, the FTC promulgated what it describes as five fair information practices designed to govern Internet privacy in concert with, as well as in the absence of, explicit regulation. Con-

KATHY L. PETTIT-O’MALLEY

University

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of

IdahoMoscow, Idaho

sumers should receive notice of a firm’s information practices, have a choice regarding subsequent uses of their infor- mation, have the ability to access infor- mation collected about them, have rea- sonable security of their personal information, and have enforcement measures available that are designed to ensure organizations’ adherence to fair information practices.

The Internet became the fastest grow- ing form of information distribution in history-in part because it is largely unregulated (Kennard, 1999). Any fail- ure to voluntarily adhere to the FTC’s fair information guidelines will ensure that calls for mandatory regulation become more vocal and more likely to be heeded. The long-term commercial success of the Internet may therefore depend on how well businesses can instill consumer trust in this largely unregulated medium. Today, however, many consumers have reason to lack confidence in the World Wide Web (Culnan, 2000). For example, in one of Culnan’s samples, less than 14% of the Web sites had any form of comprehen- sive privacy disclosure.

The ability to acquire and retain cus- tomers will also determine the success

or failure of an individual organization

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

MarcWApril2002 21 9

engaged in Internet activity (Reichheld, 1993). Managing the customer relation- ship in an interactive environment is par- ticularly challenging for electronic busi- ness ventures. A competitor’s Web site is just a mouse click away. As a conse- quence, consumer trust is a fundamental prerequisite needed for the achievement and preservation of competitiveness within this distribution channel.

Are business schools preparing stu- dents to effectively create consumer trust and deal with other related Internet privacy issues? This is a nontrivial ques- tion. Global electronic commerce has

been forecast to exceed

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

6.7 trillion dol-lars by 2004 (Sanders & Temkin,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2000). In the United States alone, electroniccommerce is expected to account for over 13% of the gross domestic product in 2004. Firms that do not enjoy the trust of consumers are unlikely to participate in the growth of sales through this distri- bution channel. Perhaps more important, industry’s disregard for consumer priva- cy is likely to lead to government regu- lation that could impede the develop- ment of Internet commerce altogether.

In this study, we examined business faculty concerns over ethical issues related to Internet privacy. We also explored the extent to which business faculty members are addressing Internet privacy issues in the classroom. Our results show somewhat ubiquitous and homogeneous concern regarding Inter- net privacy issues. Our analyses also demonstrate inconsistency among facul- ty perceptions of Internet privacy stan- dards as they exist today, as well as among the types of faculty members most likely to incorporate Internet pri- vacy materials in the classroom. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of what faculty and administrators can do to enhance the quality of classroom pre- sentation of rapidly changing business

topics, including Internet privacy.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Background

An ethical framework can serve as the means through which a bond of trust is created between a business and con- sumers (Caudill & Murphy, 2000). Almost without exception, most busi- nesses would prefer to develop repeat customer relationships. Such continuing

relationships may be based as much on trust as on any product benefits received. Previous research has shown that con- sumers only distinguish between two Internet privacy dimensions: (a) the extent to which an individual has control over his or her personal information and (b) his or her awareness of personal information gathered as a consequence of Web-based activities (Foxman & Kil- coyne, 1993; Milne, 2000).

From a consumer’s perspective, whenever a computer is logged onto the Internet, Internet privacy and consumer trust can be compromised. In the fol- lowing discussion, we identify just two ways in which privacy violations may occur and illustrate how pervasive Inter- net privacy issues are likely to become.

Personal information is frequently captured without the knowledge of con- sumers. Internet sites collect data on everything from the consumer’s type of browser and computer hardware to the time that he or she spends on a Web page and other Web sites. Web sites often leave files called cookies on a user’s computer. These files can identify con- sumers when they return to the site as well as provide a great deal of informa- tion without the consumer’s knowledge. For example, DoubleClick has merged cookies to provide complex descriptions of people’s online behavior (Baig, Stepanek, & Gross, 1999) and RealNet- works has used music software to trans- mit the specific content that each cus- tomer has listened to and has matched these data with personally identifiable information (Quittner, 1999).

Many Web sites also explicitly request personal information (e.g., visi- tor registration, warranty data, con- sumer surveys). Whether these Internet sites provide an adequate disclosure of how this information may be used is another issue. Toysmart, for instance, promised consumers that any informa- tion that they provided would never be made available to another business enti- ty without their permission. Recently, however, Toysmart was allowed to sell its customer database over the objec- tions of 39 state attorneys general (Richtel, 2000). The costs of unsolicit- ed marketing contacts, for the con- sumer, after this information has been sold and/or provided to affiliated com-

panies, are not inconsequential (Petty 2000).

We expect that most business faculty members are generally aware of Internet privacy issues and concerned about related ethical dilemmas posed by busi- ness activities on the Internet. However, the ethical framework that they use to distinguish Internet privacy issues may be quite different from the framework used by consumers. Business faculty members, for example, are expected to gravitate toward a utilitarian model of decision making (Laczniak & Murphy, 1993). In this circumstance, the incre- mental costs that an individual bears for the sale of his or her information or its use for undisclosed purposes are likely to be regarded as less consequential than the benefits conferred by market devel- opment activities. On the other hand, consumers who have had their informa- tion used in unauthorized ways are not likely to feel the same way. They often find it increasingly difficult to establish such bonds of trust subsequently.

Because of the relative newness and rapid pace of change in e-commerce, business faculty knowledge of Internet privacy issues is likely to be limited in scope and prone to error. After all, the Internet phenomenon is still evolving, and the relevant range of privacy issues is a subject of ongoing debate. But there is legislation as well as government guide- lines regarding Internet privacy, and busi- ness faculty members should be aware of this. Specifically, the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (1 999), the Feder- al Trade Commission’s Fair Information Principles (FK 1998a), and the Euro- pean Union Privacy Directive (Messmer, 1998) detail appropriate online data col- lection and dissemination of personal information in much of North America and Europe.

Besides assessing the ethical con- cerns of business faculty members, we sought to measure the extent and relia- bility of faculty knowledge regarding former Internet privacy standards. Alba and Hutchinson (2000), in a compre- hensive literature review, reported that people often become confident in their knowledge through repeated experience with a subject. But the actual correspon- dence between self-reported and objec- tive knowledge is far from perfect. Indi-

220

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

JournalzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ofzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Education for Businessviduals’ confidence in their knowledge consistently exceeds measures of their objective knowledge. Because of this tendency, business faculty members may know less about Internet privacy issues than they believe or state that they do. Business students, however, will be shortchanged if there is a dis- connect between subjective and objec- tive measures of faculty Internet privacy knowledge.

The confidence that people have in their knowledge regarding a subject has been shown to be related to the amount of time that they spend thinking about it (Koehler, 1991). In some instances, this confidence may be justified. In other instances, as in rapidly changing fields, high confidence may be unwarranted. In this study, we posited that faculty mem- bers who had spent greater amounts of time thinking about Internet privacy issues would have inflated self-evalua- tions of their Internet privacy knowl- edge. We expected that their perceived knowledge evaluations would be incon- sistent with measures of their objective

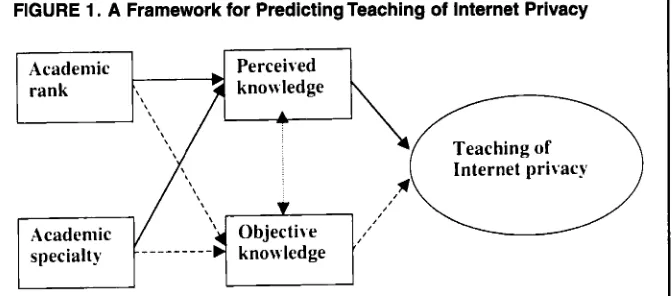

knowledge. In Figure

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1, we illustrate the framework that we thought would influ-ence what is taught and who teaches Internet privacy topics.

We expected that information sys- tems faculty members would be more likely to hold somewhat inflated beliefs about the extent of their Internet privacy knowledge than faculty members in other academic specializations. After all, information systems faculty mem- bers have spent and continue to spend a great deal of time thinking about issues related to information technology. But because of the rapidly changing nature of the Internet, their objective knowl- edge of related issues may not have kept pace. We also expected that assistant professors, fresh from years of intense study, and full professors, who over the years have accumulated a reservoir of thought, would have higher levels of perceived knowledge when compared with associate professors. Because pre- vious research conducted across many disciplines has suggested the lack of correspondence between actual and per- ceived knowledge, we measured objec- tive knowledge regarding Internet priva- cy between and among academic

[image:4.612.230.566.46.194.2]specialties and ranks.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

FIGURE 1. A Framework for Predicting Teaching of Internet Privacy

I

Acadeniic Perceived rank know ledge

Teaching

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ofInternet privacy

knot\ ledge

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Notes. The solid lines between constructs are those that proved to represent significant relation- ships. Dashed lines represent potential relationships that were not found to be significant. We tested the relationships between the teaching of Internet privacy issues and objective and per- ceived knowledge through discriminant analysis. We evaluated a potential relationship between perceived and objective knowledge with a Pearson correlation and used MANOVA to examine the relationships between academic ranWspecialty and perceivedobjective knowledge.

Method

We surveyed business faculty mem- bers at 25 institutions accredited by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). These universities were selected at random from an AACSB list of 382 currently

accredited U.S. business schools. We took a census of faculty names from each university Web site and initially contacted these individuals via e-mail. A cover letter personally addressed to each faculty member from the Director of the American Business Ethics Asso- ciation requested their participation in an Internet privacy survey and included a link to the Internet survey site.

We administered the questionnaire through an Internet survey module pro- vided by Sawtooth Software. Seventy- five business faculty members responded over the 2-week survey period. Academic rank and academic specialty distributions were virtually identical to known popula- tion parameters at the sampled institu- tions. The incidence of finance faculty members was the only exception. The percentage of finance faculty members responding was slightly lower, although not significantly lower, than the percent- age of finance faculty members actually at the sampled institutions.

The 27 questions measured ethical concerns regarding Internet privacy. We asked respondents to indicate their degree of agreement or disagreement with ethically related belief statements

on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Respon- dents were also asked to indicate, on a 5-point scale, how familiar they were with the Federal Trade Commission’s Internet Privacy Fair Information Prin- ciples. These guidelines form the basis of Internet privacy regulation in the United States. In addition, respondents provided an estimate of the number of classroom hours that they spent present- ing Internet privacy issues during an academic year. They also responded to demographic questions concerning aca- demic rank and specialty.

Finally, we asked two questions regarding respondents’ knowledge about (a) governmental regulations regarding Internet privacy and (b) the identity of the organizations that pro- vide Internet privacy certification of Web sites (i.e., notification of site priva- cy practices.) Each question required that respondents identify, from a list of six items, all those that were appropriate for the category. A correct response was classified as either inclusion of an appropriate item or the omission of (i,e., leaving blank) an item that was inappro- priate and unrelated.

Results

We factor analyzed the initial 27 questions associated with faculty ethical beliefs through quartimax rotation. In line with the findings of other researchers, we found two clearly sepa- rate dimensions relating to ethical deci-

MarcWApril2002 221

sion making with regard to Internet pri- vacy. In Table 1, we present the factor loadings of individual questionnaire items on the two identified factors. Fac-

tor

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1 (questionnaire items listed in thefirst eight rows of Table 1) related large- ly to choice and/or access issues, where- as Factor 2 (questionnaire items listed in the last seven rows) primarily related to security, disclosure, and/or enforce- ment. Because Factor 1 had both a high- er Eigen value than Factor 2 (5.957 ver- sus 2.839) and a higher percentage of

variance explained (22.1 %

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

versus 10.5%), we concluded that the surveyedfaculty members were relatively more adamant in their beliefs regarding choice and access than in their beliefs regarding security, disclosure, and enforcement.

To test the extent to which business faculty members were concerned with Internet privacy issues, we created two ethics summated measures based on the respective items that loaded highly on either factor. We conducted reliability analyses on both indices. For Ethics 1 (choice and access), the Cronbach’s

Alpha of .8078 (p

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

c

.001) indicates that the composite scale was highly reliable.Similarly, the Cronbach’s Alpha of

A381 (p

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

c .001) for Ethics 2 (security, disclosure, and enforcement) indicatesthat the latter summated index was also highly reliable.

The mean for Ethics 1 (choice and access) was 2.067, indicating that the business faculty members were proba- bly more comfortable with Internet companies’ control of the ownership and use of personal or behavioral data obtained via the Internet than were con- sumers. For Ethics 2 (security, disclo- sure and access), the mean of 4.34 indi- cates that business faculty members generally agreed that consumers should be made aware of Internet information- gathering practices as well as have their personal information protected by rea- sonable security measures. These find- ings are consistent with the utilitarian framework that we had posited for busi- ness school faculty.

We performed a MANOVA to see if position on ethical Internet issues dif- fered by faculty rank or field. Neither rank (Wilks’s Lambda = .845), nor field

(Wilks’s Lambda = .961), nor their inter-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TABLE 1. Factor Loadings of Ethics-Related Questionnaire Items

Factor 2:

Security/ Questionnaire items Choice/access disclosure

Factor 1: enforcemenu

Consumers implicitly grant permission to collect personal information whenever they provide data as a condition of Web-site access.

The monitoring of Internet behavior is the same as observing shopping behavior in a store.

The intention behind Internet infor- mation gathering is to provide consumers with greater value. Installing software programs or

cookies on someone’s computer with- out permission violates personal privacy rights.

Information gathered by a company as part of an Internet transaction belongs to the f i i .

permission before information may be gathered from young children. victimized by the selling of personal information gathered on the Internet. Internet privacy, as it exists today, is

consistent with the amount of

privacy afforded to consumers in other types of commercial activity. played on every Web site. information gathered about them will be used.

consumers is restricted to the specific purpose disclosed.

Consumers must provide explicit permission for the gathering of any of their personal information on the Internet.

commercial Web site is prosecutable. the security procedures used for safe- guarding their information.

Governments have a duty to protect the on-line privacy of their citizens. Eigen value

Percentage variance explained by factor Parents must provide verifiable Vulnerable consumer groups are

A privacy statement must be dis-

Consumers must be informed on how The use of data collected from

Deceptive information posted to a Consumers must be informed about

.656

,613

.63 1

.534

.726

.540

.645

.621

-.094

-.069

-.018

-.356

-.097

-.

180 -.446 5.95722.1

-.

145-. 125

-. 138 .008

-.039

.005

-.097

-.129

.616

.913

,797

,739

.625

.775

,437 2.839 10.5

Nore. Quartimax rotation was used in the factor analysis. Reverse-scaled items have had corre-

sponding sign changes in factor loadings.

222 Journal of Education for

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Businessactive effect (Wilks’s Lambda

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

= .816)were significant, indicating that position on ethical Internet privacy issues was reasonably homogeneous throughout the sampled business faculty.

We were also interested in determin- ing objective knowledge regarding Internet privacy issues. Two question- naire items were relevant: The first related to the organizations that provide privacy certification of Web sites and the second concerned the regulations that govern Internet information gather- ing. Each of these two questions required that respondents identify, from a list of six items, all those that were

appropriate for the category. As in the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

previous questions, a correct response was classified as either inclusion of an appropriate item or omission of (leaving blank) an item that was inappropriate and unrelated. Thus, for each of the six subitems in either question, we had a dichotomous variable.

We created a ratio-scale index for each question by computing the per- centage of correctly identified subitems. We conducted reliability tests on each “knowledge” question. Because the original data were dichotomous, the appropriate reliability statistic is Cochran’s Q. Cochran’s Q for SITE- KNOW (i.e., knowledge of which orga- nizations provide privacy certification of Web sites) was 195.99 (p <.001). Thus, the SITEKNOW index was found to be highly reliable. Similarly, the REGKNOW variable (i.e., what regula- tions govern Internet information gath- ering) was also determined to be highly reliable, with a Cochran’s Q of 139.86

(p

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

c .001). Because the determination of which of a question’s six subitemsshould be included or excluded was directly based on objective criteria (cer- tification and regulation), the measures are necessarily valid.

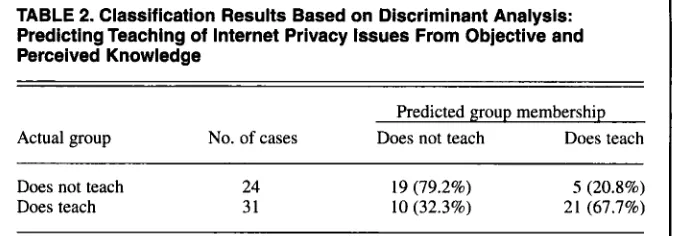

We previously postulated that the extent to which a business school facul- ty member teaches Internet privacy issues would be related to his or her knowledge of the subject. However, we hypothesized that his or her perceived knowledge, perhaps more so than objec- tive knowledge, would affect the faculty member’s coverage decisions regarding particular class topics. Consequently, we performed a discriminant analysis in

which we used measures of both actual and perceived knowledge to predict whether or not a faculty member taught Internet privacy issues.

The composite variable that we creat- ed of actual knowledge incorporated the percentage of correct responses to the SITEKNOW and REGKNOW ques- tions. Thus, we had a measure of objec- tive knowledge that potentially ranged from .OO to 1.00. The perceived knowl- edge measurement came directly from the 5-item question asking how familiar the respondent was with the Federal Trade Commission’s Internet Privacy Fair Information Principles. Higher val- ues of the variable represented higher levels of perceived knowledge. Together, objective knowledge and perceived knowledge were highly significant in predicting which business faculty mem- bers taught or did not teach Internet pri- vacy issues (Wilks’s Lambda = 349,

equivalent F

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

= 9 . 3 8 , ~ < .01). The model correctly predicted 72.7% of cases, com-pared with a chance level of 50%. We present classification results in Table 2.

When we examined the discriminant analysis carefully, however, we found that only the perceived knowledge vari- able entered the solution. Perceived knowledge-not objective knowl- edge-was the significant predictor regarding which respondents taught Internet privacy issues. It is possible that because objective and perceived knowledge may be correlated, the result could be arbitrary. To ascertain whether objective knowledge predicted teaching of Internet privacy issues nearly as well, we conducted a second discriminant analysis in which we used only objec- tive knowledge as a predictor. In that analysis, teaching could not be predict-

ed beyond the chance level (Wilks’s Lambda = .984, not significant). We therefore concluded that what the instructor thinks he or she knows about Internet privacy issues, and not his or her actual knowledge, affects his or her decision regarding what material to teach. Furthermore, a Pearson Correla- tion between objective and perceived knowledge, though slightly positive, was not significant ( r = .1330, p = ,329). We also hypothesized that perceived knowledge would mediate the relation- ship between characteristics of the facul- ty members and their decision to cover Internet privacy issues in class. To test the relationship of individual difference characteristics of faculty members to perceived knowledge, we performed a

MANOVA in which both objective and

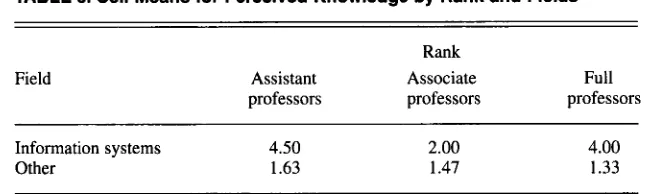

perceived knowledge were treated as dependent variables. The results showed that academic rank (assistant, associate, and full professor) and field (informa- tion systems as opposed to all others) affected perceived knowledge much more than they affected objective knowl- edge. Rank had a significant effect on perceived knowledge ( F = 6.15, p < .01) but not on objective knowledge ( F = .89, not significant). Those more likely to have higher perceived knowledge tended to be either assistant professors (more recently trained-as we had hypothe- sized) or full professors (also as we pre- dicted). In Table 3, we show cell means for perceived knowledge broken down by rank and field.

Similar to rank, the main effect of field was significant when it concerned perceived knowledge ( F = 27.51, p <

.OOl) but not significant when it con- cerned objective knowledge ( F = .08).

[image:6.612.230.567.583.701.2]Finally, the interactive effect of rank and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TABLE 2. Classification Results Based on Discriminant Analysis: Predicting Teaching of Internet Privacy Issues From Objective and Perceived Knowledge

Predicted group membership Actual group No. of cases Does not teach Does teach

I

Does not teach 24 Does teach 31

I

19 (79.2%) 5 (20.8%)10 (32.3%) 21 (67.7%)

Nores. Percentage of cases correctly classified was 72.73%. Only perceived knowledge entered the equation.

MarcWApril2002

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

223

TABLE 3. Cell Means for Perceived Knowledge by Rank and Fields

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Field

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Rank

Assistant Associate Full

professors professors professors

Information systems 4.50

Other 1.63

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2.00

1.47

4.00

1.33

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Notes. Scale values on the perceived knowledge item range from 1 to

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 , with higher valuesrepresenting greater perceived knowledge. Duncan’s Multiple Range Tests showed tat IS assis- tant and full professors had significantly higher perceived knowledge than all other groups,

at p < .05.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

field mirrored the other tests. Specifical- ly, RANK X FIELD affected perceived

knowledge significantly ( F = 5.28, p

c

. O l ) but was unrelated to objective knowledge ( F = 1.40, not significant).

As can be seen from the data in Table 3,

the assistant and full professors of infor- mation systems believed that they had more knowledge of Internet privacy issues than did other faculty members. This greater perceived knowledge, in turn, resulted in their being more inclined to teach the topic. However, their greater perceived knowledge was unrelated to measures of their objective knowledge of Internet privacy issues.

Conclusions

Apparently, not enough discussion of Internet privacy issues is taking place across the business curriculum. In our study, 80% of the reporting faculty mem- bers spent 3 or fewer hours discussing

Internet privacy issues annually. Our other findings, although not unexpected, are even more disturbing. In particular, we refer to the discrepancy between fac- ulty perceptions of their knowledge and objective measures of the same. Most faculty members failed to correctly clas- sify the majority of objective Internet pri-

vacy items. Furthermore, the better informed faculty (i.e., those who correct- ly classified at least 50% of the items) were not the instructors who reported spending more time teaching Internet privacy issues in the classroom.

These results are particular to Internet privacy issues-a rapidly evolving topic.

However, our results serve as a caution-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ary note to any business faculty member whose field is changing more rapidly

than his or her own skill set. Because many instructors are asked to teach top- ics outside of their specialties, they should receive support in acquiring the requisite knowledge before being asked to present topical coverage in class. However, this does not always happen.

The total amount of time spent “teach- ing” Internet privacy issues may involve time spent presenting both related legal and ethical material. Ideally, if an instruc- tor spends more time discussing ethical aspects of Internet privacy, he or she should still provide students with accu- rate information concerning current regu- lations and industry practices. In our study, most of the respondent faculty members who spent class time on some aspect of Internet privacy lacked such knowledge. This, however, should not be construed to suggest that the faculty members were disseminating inaccurate information on those topics. They may have chosen to focus their discussions on normative questions about what the status of Internet privacy practices should be.

The apparent hole in the body of Inter- net privacy objective knowledge means that business faculty members should focus exclusively on gaining and main- taining an objective knowledge base on the subject. Faculty members may bene- fit at least as much from ethical training that ensures that they understand the eth- ical perspective of consumers. Disclosing data-gathering procedures and security and enforcement policies may be insuffi- cient in establishing consumer trust and building long-lasting customer relation- ships. For example, consumers who suf- fer from information overload are unlike- ly to comprehend fully a detailed privacy disclosure if they read it at all. They will

not blame themselves, however, when their personal information is used for pur- poses of which they disapprove.

In the future, researchers should investigate whether discrepancies be- tween objective and perceived knowl- edge have occurred in other business disciplines, both those that have evolved rapidly and those that have not under- gone fundamental shifts in content. If more discrepancies between objective and perceived knowledge are identified in rapidly evolving topics, they would indicate a critical need for support sys- tems that would improve instructor training. This support can be provided

by one’s college or university, by pub-

lishing companies with topically related texts, or by the professional organiza- tions to which business faculty mem- bers belong. Faculty development semi- nars, on-line support materials from textbook publishers, and workshops at professional meetings are just a few ways through which continuing educa- tion needs may be met.

For the time being, faculty members across the business curriculum must concentrate on enhancing their objec- tive knowledge of Internet privacy issues as well as broadening their ethi- cal discussions to include consumer perspectives. These concerns should not be regarded as the exclusive responsibil- ity of information systems faculty. The

Internet and corresponding privacy issues will affect every business disci- pline to some degree. Only when such issues are integrated throughout the cur- riculum and emphasized by diverse fac- ulty members can we ensure that stu- dents are imprinted with the importance of potential Internet privacy dilemmas. Government regulation of Internet com- merce will only increase if business fac- ulty and practitioners do not take a proactive stance to reduce the incidence of consumer privacy violations.

REFERENCES

Alba,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

J. W., & Hutchinson, J. W. (2000). Knowl- edge calibration: What consumers know andwhat they think they know. Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Con-sumer Research, 27(2), 123-156.

Baig, E. C., Stepanek, M., & Gross, N. (1999, April

5). Privacy on the Net. Business Week, 84-90.

Blattberg, R . , Glazer, R., & Little, J. (1994). The marketing information revolution. Boston: Har-

vard Business School Press.

224 Journal of Education for Business

[image:7.612.53.383.49.146.2]Caudill, E. M.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Murphy, P. E. (2000). Consumer online privacy: Legal and ethical issues.zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Jour- nal of Public Policy and Marketing, 19(1),7-19.

Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act:

Issuance of Final Rule. (1999). 64

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Federal Reg- ister.Culnan, M. J. (2000). Protecting privacy online: Is self-regulation working? Journal of Public Pol-

icy and Marketing, I9( l), 20-26.

Federal Trade Commission. (1998a, June). Priva-

cy online: A report to Congress. Washington, DC: Author.

Federal Trade Commission (l998b. July 21). Con-

sumer privacy on the World Wide Web (Pre- pared statement presented to the Subcommittee on Telecommunications, Trade and Consumer Protection of the House Committee of Com-

merce,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

U.S. House of Representatives). Wash- ington, DC: AuthocFox, S. (2000, August 20).Trust and privacy online: Why Americans want to rewrite the rules. San Francisco: Pew Inter- net and American Life Project, Tides Center. Foxman, E. R., & Kilcoyne, P. (1993). Informa-

tion technology, marketing practice, and con- sumer privacy. Journal of Public Policy and

Marketing,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

12(1), l o b 1 19.Green, H. (1998, March 16). A little privacy please. Business Week, 98-102.

Honigan, J. B. (2000, September 25). New Inter-

net users: What they do online, what they don’t, and implications f o r the Net’s future. San Fran- cisco: Pew Internet and American Life Project, Tides Center.

Kennard, W. E. (1999, March 11). A stable mar-

ket, a dynamic Internet. Speech presented before Legg Mason by the Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, Wash- ington, DC.

Koehler, D. J. (1991). Explanation, imagination, and confidence in judgement. Psychological

Bulletin, 110(November), 499-5 19.

Laczniak, G. R., & Murphy, P. E. (1993). Ethical

marketing decisions: The higher mad (p. 17). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Lenhart, A. (2000, September 21). Who’s not

online:

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

57% of those without Internet accesssay they do not plan to log on. San Francisco:

Pew Internet and American Life Project, Tides Center.

Messmer, E. (1998, December 7). U.S., Europe at

impasse over privacy. Network World, 49.

Milne, G. R. (2000). Privacy and ethical issues in databasehnteractive marketing and public poli-

cy: A research framework and overview of the special issue. Journal of Public Policy and

Marketing, 19(1), 1-6.

Miyazaki. A. D., & Fernandez, A. (2000). Internet privacy and security: An examination of online retailer disclosure. Journal of Public Policy and

Marketing, 19(1), 54-61.Petty. R. D. (2000). Marketing without consent: Consumer choice

and costs, privacy, and public policy. Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ojPublic Policy and Marketing, 19( 1). 42-53.Pri- vacy and American Business. (1997). Com-

merce, communication and privacy online:

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Anational survey of computer users. Hackensack, NJ: Author.

Quittner, J. (1999, November 15). Big Brother was listening: RealNetworks’ Online-Jukebox software turns out to be not buggy but bugged.

Time, 1 16.

Reichheld, F. F. (1993). Loyalty-based manage- ment. Harvard Business Review, March/April, 64-73.

Richtel, M. (2000, July 22). Toysmart.com in set- tlement with FTC. New York Times, C1. Sanders, M. R., & Temkin, B. D. (2000, April 18).

Global ecommerce approaches hypergrowth.

Cambridge, MA: The Forrester Brief, Forrester Research Inc.