EDITORS-IN-CHIEF

Marshall M. Haith received his M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from U.C.L.A. and then carried out postdoctoral work at Yale University from 1964–1966. He served as Assistant Professor and Lecturer at Harvard University from 1966–1972 and then moved to the University of Denver as Professor of Psychology, where he has conducted research on infant and children’s perception and cognition, funded by NIH, NIMH, NSF, The MacArthur Foundation, The March of Dimes, and The Grant Foundation. He has been Head of the Developmental Area, Chair of Psychology, and Director of University Research at the University of Denver and is currently John Evans Professor Emeritus of Psychology and Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center.

Dr. Haith has served as consultant for Children’s Television Workshop (Sesame Street), Bilingual Children’s Television, Time-Life, and several other organizations. He has received several personal awards, including University Lecturer and the John Evans Professor Award from the University of Denver, a Guggenheim Fellowship for serving as Visiting Professor at the University of Paris and University of Geneva, a NSF fellowship at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences (Stanford), the G. Stanley Hall Award from the American Psychological Association, a Research Scientist Award from NIH (17 years), and the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award from the Society for Research in Child Development.

Janette B. Benson earned graduate degrees at Clark University in Worcester, MA in 1980 and 1983. She came to the University of Denver in 1983 as an institutional postdoctoral fellow and then was awarded an individual NRSA postdoctoral fellowship. She has received research funding form federal (NICHD; NSF) and private (March of Dimes, MacArthur Foundation) grants, leading initially to a research Assistant Professor position and then an Assistant Professorship in Psychology at the University of Denver in 1987, where she remains today as Associate Professor of Psychology and as Director of the undergraduate Psychology program and Area Head of the Developmental Ph.D. program and Director of University Assessment. Dr. Benson has received various awards for her scholarship and teaching, including the 1993 United Methodist Church University Teacher Scholar of the Year and in 2000 the CASE Colorado Professor of the Year. Dr. Benson was selected by the American Psychological Association as the 1995–1996 Esther Katz Rosen endowed Child Policy Fellow and AAAS Congressional Science Fellow, spending a year in the United States Senate working on Child and Education Policy. In 1999, Dr. Benson was selected as a Carnegie Scholar and attended two summer institutes sponsored by the Carnegie Foundation program for the Advancement for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Palo Alto, CA. In 2001, Dr. Benson was awarded a Susan and Donald Sturm Professorship for Excellence in Teaching. Dr. Benson has authored and co-authored numerous chapters and research articles on infant and early childhood development in addition to co-editing two books.

EDITORIAL BOARD

Richard Aslinis the William R. Kenan Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at the University of Rochester and is also the director of the Rochester Center for Brain Imaging. His research has been directed to basic aspects of sensory and perceptual development in the visual and speech domains, but more recently has focused on mechanisms of statistical learning in vision and language and the underlying brain mechanisms that support it. He has published over 100 journal articles and book chapters and his research has been supported by NIH, NSF, ONR, and the Packard and McDonnell Foundations. In addition to service on grant review panels at NIH and NSF, he is currently the editor of the journalInfancy. In 1981 he received the Boyd R. McCandless award from APA (Division 7), in 1982 the Early Career award from APA (developmental), in 1988 a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim foundation, and in 2006 was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Warren O. Eatonis Professor of Psychology at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada, where he has spent his entire academic career. He is a fellow of the Canadian Psychological Association, and has served as the editor of one of its journals, the Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. His current research interests center on child-to-child variation in developmental timing and how such variation may contribute to later outcomes.

Robert Newcomb Emde is Professor of Psychiatry, Emeritus, at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. His research over the years has focused on early socio-emotional development, infant mental health and preventive interventions in early childhood. He is currently Honorary President of the World Association of Infant Mental Health and serves on the Board of Directors of Zero To Three.

Hill Goldsmith is Fluno Bascom Professor and Leona Tyler Professor of Psychology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He works closely with Wisconsin faculty in the Center for Affective Science, and he is the coordinator of the Social and Affective Processes Group at the Waisman Center on Mental Retardation and Human Development. Among other honors, Goldsmith has received an National Institute of Mental Health MERIT award, a Research Career Development Award from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the James Shields Memorial Award for Twin Research from the Behavior Genetics Association, and various awards from his university. He is a Fellow of AAAS and a Charter Fellow of the Association for Psychological Science. Goldsmith has also served the National Institutes of Health in several capacities. His editorial duties have included a term as Associate Editor of one journal and membership on the editorial boards of the five most important journals in his field. His administrative duties have included service as department chair at the University of Wisconsin.

Richard B. Johnston Jr. is Professor of Pediatrics and Associate Dean for Research Development at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and Associate Executive Vice President of Academic Affairs at the National Jewish Medical & Research Center. He is the former President of the American Pediatric Society and former Chairman of the International Pediatric Research Foundation. He is board certified in pediatrics and infectious disease. He has previously acted as the Chief of Immunology in the Department of Pediatrics at Yale University School of Medicine, been the Medical Director of the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, Physician-in-Chief at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Chair of the Department of Pediatrics at the University Pennsylvania School of Medicine. He is editor of ‘‘Current Opinion in Pediatrics’’ and has formerly served on the editorial board for a host of journals in pediatrics and infectious disease. He has published over 80 scientific articles and reviews and has been cited over 200 times for his articles on tissue injury in inflammation, granulomatous disease, and his New England Journal of Medicine article on immunology, monocytes, and macrophages.

Jerome Kagan is a Daniel and Amy Starch Professor of Psychology at Harvard University. Dr. Kagan has won numerous awards, including the Hofheimer Prize of the American Psychiatric Association and the G. Stanley Hall Award of the American Psychological Association. He has served on numerous committees of the National Academy of Sciences, The National Institute of Mental Health, the President’s Science Advisory Committee and the Social Science Research Council. Dr. Kagan is on the editorial board of the journalsChild DevelopmentandDevelopmental Psychology, and is active in numerous professional organizations. Dr. Kagan’s many writings include Understanding Children: Behavior, Motives, and Thought, Growth of the Child, The Second Year: The Emergence of Self-Awareness, and a number of cross-cultural studies of child development. He has also coauthored a widely used introductory psychology text. Professor Kagan’s research, on the cognitive and emotional development of a child during the first decade of life, focuses on the origins of temperament. He has tracked the development of inhibited and uninhibited children from infancy to adolescence. Kagan’s research indicates that shyness and other temperamental differences in adults and children have both environmental and genetic influences.

Rachel Keen(formerly Rachel Keen Clifton) is a professor at the University of Virginia. Her research expertise is in perceptual-motor and cognitive development in infants. She held a Research Scientist Award from the National Institute of Mental Health from 1981 to 2001, and currently has a MERIT award from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. She has served as Associate Editor of Child Development (1977–1979), Psychophysiology (1972–1975), and as Editor of SRCD Monographs (1993–1999). She was President of the International Society on Infant Studies from 1998–2000. She received the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award from the Society for Research in Child Development in 2005 and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Science in 2006.

Ellen M. Markmanis the Lewis M. Terman Professor of Psychology at Stanford University. Professor Markman was chair of the Department of Psychology from 1994–1997 and served as Cognizant Dean for the Social Sciences from 1998–2000. In 2003 she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and in 2004 she was awarded the American Psychological Association’s Mentoring Award. Professor Markman’s research has covered a range of issues in cognitive development including work on comprehension monitoring, logical reasoning and early theory of mind development. Much of her work has addressed questions of the relationship between language and thought in children focusing on categorization, inductive reasoning, and word learning.

Yuko Munakata is Professor of Psychology at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Her research investigates the origins of knowledge and mechanisms of change, through a combination of behavioral, computational, and neuroscientific methods. She has advanced these issues and the use of converging methods through her scholarly articles and chapters, as well as through her books, special journal issues, and conferences. She is a recipient of the Boyd McCandless Award from the American Psychological Association, and was an Associate Editor ofPsychological Review, the field’s premier theoretical journal.

Arnold J. Sameroff, is Professor of Psychology at the University of Michigan where he is also Director of the Development and Mental Health Research Program. His primary research interests are in understanding how family and community factors impact the development of children, especially those at risk for mental illness or educational failure. He has published 10 books and over 150 research articles including theHandbook of Developmental Psychopathology, The Five to Seven Year Shift: The Age of Reason and Responsibility, and the forthcomingTransactional Processes in Development. Among his honors are the Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award from the Society for Research in Child Development and the G. Stanley Hall Award from the American Psychological Association. Currently he is President of the Society for Research in Child Development and serves on the executive Committee of the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development.

FOREWORD

This is an impressive collection of what we have learned about infant and child behavior by the researchers who have contributed to this knowledge. Research on infant development has dramatically changed our perceptions of the infant and young child. This wonderful resource brings together like a mosaic all that we have learned about the infant and child’s behavior. In the 1950s, it was believed that newborn babies couldn’t see or hear. Infants were seen as lumps of clay that were molded by their experience with parents, and as a result, parents took all the credit or blame for how their offspring turned out. Now we know differently.

The infant contributes to the process of attaching to his/her parents, toward shaping their image of him, toward shaping the family as a system, and toward shaping the culture around him. Even before birth, the fetus is influenced by the intrauterine environment as well as genetics. His behavior at birth shapes the parent’s nurturing to him, from which nature and nurture interact in complex ways to shape the child.

Geneticists are now challenged to couch their findings in ways that acknowledge the complexity of the interrelation between nature and nurture. The cognitivists, inheritors of Piaget, must now recognize that cognitive development is encased in emotional development, and fueled by passionately attached parents. As we move into the era of brain research, the map of infant and child behavior laid out in these volumes will challenge researchers to better understand the brain, as the basis for the complex behaviors documented here. No more a lump of clay, we now recognize the child as a major contributor to his own brain’s development.

This wonderful reference will be a valuable resource for all of those interested in child development, be they students, researchers, clinicians, or passionate parents.

T. Berry Brazelton, M.D. Professor of Pediatrics, Emeritus Harvard Medical School Creator, Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS) Founder, Brazelton Touchpoints Center

PREFACE

Encyclopedias are wonderful resources. Where else can you find, in one place, coverage of such a broad range of topics, each pursued in depth, for a particular field such as human development in the first three years of life? Textbooks have their place but only whet one’s appetite for particular topics for the serious reader. Journal articles are the lifeblood of science, but are aimed only to researchers in specialized fields and often only address one aspect of an issue. Encyclopedias fill the gap.

In this encyclopedia readers will find overviews and summaries of current knowledge about early human development from almost every perspective imaginable. For much of human history, interest in early development was the province of pedagogy, medicine, and philosophy. Times have changed. Our culling of potential topics for inclusion in this work from textbooks, journals, specialty books, and other sources brought home the realization that early human development is now of central interest for a broad array of the social and biological sciences, medicine, and even the humanities. Although the ‘center of gravity’ of these volumes is psychology and its disciplines (sensation, perception, action, cognition, language, personality, social, clinical), the fields of embryology, immunology, genetics, psychiatry, anthropol-ogy, kinesiolanthropol-ogy, pediatrics, nutrition, education, neuroscience, toxicology and health science also have their say as well as the disciplines of parenting, art, music, philosophy, public policy, and more.

Quality was a key focus for us and the publisher in our attempts to bring forth the authoritative work in the field. We started with an Editorial Advisory Board consisting of major contributors to the field of human development – editors of major journals, presidents of our professional societies, authors of highly visible books and journal articles. The Board nominated experts in topic areas, many of them pioneers and leaders in their fields, whom we were successful in recruiting partly as a consequence of Board members’ reputations for leadership and excellence. The result is articles of exceptional quality, written to be accessible to a broad readership, that are current, imaginative and highly readable.

Interest in and opinion about early human development is woven through human history. One can find pronounce-ments about the import of breast feeding (usually made by men), for example, at least as far back as the Greek and Roman eras, repeated through the ages to the current day. Even earlier, the Bible provided advice about nutrition during pregnancy and rearing practices. But the science of human development can be traced back little more than 100 years, and one can not help but be impressed by the methodologies and technology that are documented in these volumes for learning about infants and toddlers – including methods for studying the role of genetics, the growth of the brain, what infants know about their world, and much more. Scientific advances lean heavily on methods and technology, and few areas have matched the growth of knowledge about human development over the last few decades. The reader will be introduced not only to current knowledge in this field but also to how that knowledge is acquired and the promise of these methods and technology for future discoveries.

CONTENTS

Several strands run through this work. Of course, the nature-nurture debate is one, but no one seriously stands at one or the other end of this controversy any more. Although advances in genetics and behavior genetics have been breathtaking, even the genetics work has documented the role of environment in development and, as Brazelton notes in his foreword, researchers acknowledge that experience can change the wiring of the brain as well as how actively the genes are expressed. There is increasing appreciation that the child develops in a transactional context, with the child’s effect on the parents and others playing no small role in his or her own development.

There has been increasing interest in brain development, partly fostered by the decade of the Brain in the 1990s, as we have learned more about the role of early experience in shaping the brain and consequently, personality, emotion, and

intelligence. The ‘brainy baby’ movement has rightly aroused interest in infants’ surprising capabilities, but the full picture of how abilities develop is being fleshed out as researchers learn as much about what infants can not do, as they learn about what infants can do. Parents wait for verifiable information about how advances may promote effective parenting.

An increasing appreciation that development begins in the womb rather than at birth has taken place both in the fields of psychology and medicine. Prenatal and newborn screening tools are now available that identify infants at genetic or developmental risk. In some cases remedial steps can be taken to foster optimal development; in others ethical issues may be involved when it is discovered that a fetus will face life challenges if brought to term. These advances raise issues that currently divide much of public opinion. Technological progress in the field of human development, as in other domains, sometimes makes options available that create as much dilemma as opportunity.

As globalization increases and with more access to electronic communication, we become ever more aware of circumstances around the world that affect early human development and the fate of parents. We encouraged authors to include international information wherever possible. Discussion of international trends in such areas as infant mortality, disease, nutrition, obesity, and health care are no less than riveting and often heartbreaking. There is so much more to do.

The central focus of the articles is on typical development. However, considerable attention is also paid to psychological and medical pathology in our attempt to provide readers with a complete picture of the state of knowledge about the field. We also asked authors to tell a complete story in their articles, assuming that readers will come to this work with a particular topic in mind, rather than reading the Encyclopedia whole or many articles at one time. As a result, there is some overlap between articles at the edges; one can think of partly overlapping circles of content, which was a design principle inasmuch as nature does not neatly carve topics in human development into discrete slices for our convenience. At the end of each article, readers will find suggestions for further readings that will permit them to take off in one neighboring direction or another, as well as web sites where they can garner additional information of interest.

AUDIENCE

Articles have been prepared for a broad readership, including advanced undergraduates, graduate students, professionals in allied fields, parents, and even researchers for their own disciplines. We plan to use several of these articles as readings for our own seminars.

A project of this scale involves many actors. We are very appreciative for the advice and review efforts of members of the Editorial Advisory Board as well as the efforts of our authors to abide by the guidelines that we set out for them. Nikki Levy, the publisher at Elsevier for this work, has been a constant source of wise advice, consolation and balance. Her vision and encouragement made this project possible. Barbara Makinster, also from Elsevier, provided many valuable suggestions for us. Finally, the Production team in England played a central role in communicating with authors and helping to keep the records straight. It is difficult to communicate all the complexities of a project this vast; let us just say that we are thankful for the resource base that Elsevier provided. Finally, we thank our families and colleagues for their patience over the past few years, and we promise to ban the words ‘‘encyclopedia project’’ from our vocabulary, for at least a while.

PERMISSION ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following material is reproduced with kind permission of Oxford University Press Ltd Figure 1 of Self-Regulatory Processes

http:/ /www.oup.co.uk/

The following material is reproduced with kind permission of AAAS Figure 1 of Maternal Age and Pregnancy

Figures 1a, 1b and 1c of Perception and Action http:/ /www.scie ncema g.or g

The following material is reproduced with kind permission of Nature Publishing Group Figure 2 of Self-Regulatory Processes

http:/ /www.na ture.com/nat ure

The following material is reproduced with kind permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd Figure 4b of Visual Perception

A

Abuse, Neglect, and Maltreatment of Infants

D Benoit and J Coolbear,University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada

A Crawford,University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada

ã2008 D Benoit. Published by Elsevier Inc.

Glossary

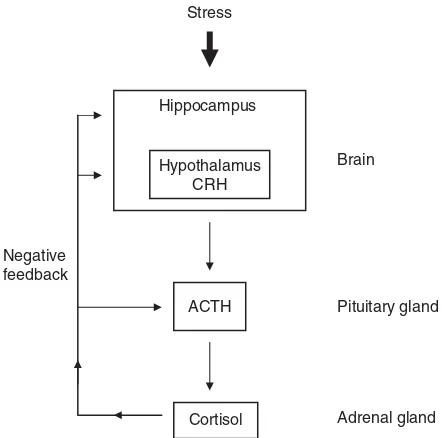

Adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (ACTH)– Hormone released from the pituitary gland through the action of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) as part of the hormonal cascade triggered by stress. ACTH then acts on the adrenal glands to stimulate the release of cortisol.

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) system– In response to stress, a hormonal cascade is triggered by the release of CRH from the hypothalamus. Release is influenced by stress, by blood levels of cortisol, and by the sleep/wake cycle. CRH activates the release of ACTH, which in turn stimulates the release of cortisol from the adrenal glands.

Cortisol– Stress hormone that mediates the body’s alarm response to stressful situations. It is

produced by the adrenal glands as a result of stimulation by ACTH. Cortisol, secreted into the blood circulation, affects many tissues in the body, including the brain.

Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis– The HPA axis is one of the two stress response

systems of the body (the other is the

sympathetic–adrenal–medullary system), which consists of the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands. The HPA axis activates and coordinates the stress response, through the action of hormones, by receiving and interpreting

information from other areas of the brain (amygdala and hippocampus) and from the autonomic nervous system.

Reported case of maltreatment– A case where physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, neglect, or exposure to interpersonal violence is suspected and reported to a child protection agency. In many

jurisdictions, the reporting of cases of suspected child maltreatment is required by law.

Substantiated case of maltreatment– A case where child maltreatment is confirmed following an investigation.

Introduction

The history of childhood is a nightmare from which we have only recently begun to awake. The further back in history one goes, the lower the level of child care and the more likely children are to be killed, abandoned, beaten, terrorized and abused.

Lloyd De Mause,The History of Childhood

Infant maltreatment has existed across all cultures, all socioeconomic strata, and in all historical epochs. In fact, there is evidence of infanticide from antiquity. The increasing recognition that children have the right to protection, and that they are not the property of their caregivers, led to the modern child protection movement. In 1874, the advocacy of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in the case of Mary Ellen, a young girl who was severely abused by her stepmother, led to an unprecedented judicial intervention and protection. Shortly afterward, the New York Society for the Preven-tion of Cruelty to Children was established, which gave rise to the founding of similar societies. Since then the complex social and familial dynamics of child maltreat-ment have been increasingly recognized. It was not until 1962, however, following a medical symposium the pre-vious year, that several physicians, headed by Denver physician C. Henry Kempe, published the landmark the ‘battered child syndrome’ in the Journal of the American

Medical Association. The battered child syndrome described a pattern of child abuse that included both physical and psychological aspects and established it as an area of aca-demic and clinical focus. In the early twenty-first century, the enormous social burden of child maltreatment remains timely, unresolved, and an important public health and policy issue. Every day, clinicians and investigators con-tinue to attend to individual infants and children who are maltreated and make their way through the complex-ities of healthcare and judicial systems. The impact of maltreatment on infants and children, particularly early and repeated abuse, is one of the most significant emo-tional and psychological traumas that a child can endure. Unlike other traumatic events in which the infant or child may be soothed by the ameliorating comforting of their caregiver, child maltreatment is most often committed by a caregiver or attachment figure. This double rupture, the lost sense of the safety and predictability of the world, and the loss of caregiver protection and security, make maltreatment a breach of profound magnitude for many infants.

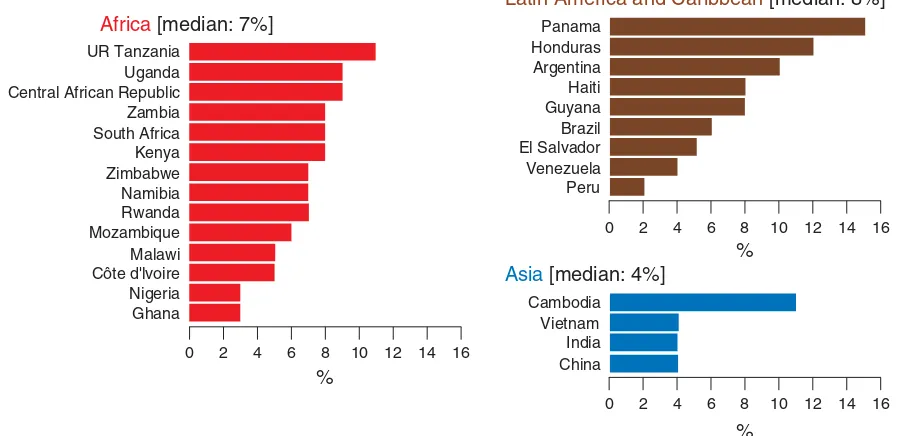

Incidence and Prevalence

The incidence and prevalence rates of maltreatment in infancy (i.e., ages 0–3 years) are difficult to ascertain, in part because of the lack of universally accepted definitions of various types of maltreatment across countries. Further, there is consensus that much maltreatment goes unreported and that each year infants die as a result of their caregivers maltreating them. In the US,3 million reports of child abuse or neglect are made each year and at least 1.5 million are substantiated. In Canada, recent data indicate that, in 2003, over 38 child abuse investigations per 1000 children were conducted and nearly half of the cases were sub-stantiated. Estimates from various European and Eastern European countries reveal that between 3 and 360/1000 of children are maltreated. The wide range of incidence and prevalence rates reflect the varying definitions of maltreat-ment used in various jurisdictions around the world and the inconsistent reporting, investigation, and recording practices. In every country where relevant data have been collected, neglect occurs up to three times as often as abuse and incidence rates of maltreatment are highest for infants from birth to age 3 years.

Definitions

There are no universally accepted definitions of infant or child maltreatment. Definitions also vary depend-ing on the professional discipline involved (e.g., child protection, law enforcement, judiciary, clinical). This

inconsistency hinders the collection of reliable vital statis-tics and interferes with scientific research on infant mal-treatment. The lack of universally accepted definitions of maltreatment may also contribute to delays in protecting maltreated infants and in providing them and their families with adequate assessment and intervention.Table 1 lists various definitions of child maltreatment.

Risk Factors for Maltreatment

Infant maltreatment occurs in complex social and inter-personal circumstances. There is no single factor that predicts risk to an infant, and the absence of identifiable risk factors does not confer immunity from maltreatment. Rather, a profile of risk indicators must be considered within the individual, familial, economic, and social con-texts of each infant. Most of the data on risk indicators for child maltreatment come from the study of child physical and sexual abuse. Data regarding risk indicators for emo-tional abuse and neglect are limited. Risk indicators may be broadly separated into child and household or caregiver characteristics. Further, there is support for the position that environmental factors beyond the child’s immediate family or household – such as factors within the local community – may also play a role in creating high-risk caregiving situations. This perspective on the human ecology of child maltreatment posits that social impover-ishment, such as low socioeconomic neighborhoods, poor community social support networks, observable criminal behavior within the community, poor housing condi-tions, and poor access to social services and programs, are environmental correlates of child maltreatment, and that rates of child maltreatment may be responsive to social change. Most information about risk factors related to child maltreatment comes from research on children older than age 3 years and this is reflected in the informa-tion provided in the following.

Child Factors

1. Age. American epidemiologic data indicate that inci-dence rates for child maltreatment are highest in infants, up to age 3 years.

that relied on reports by child protection workers, found that child functioning, in the areas of physical, cognitive, behavioral, and/or emotional health, is esti-mated to be impaired in50% of cases where child maltreatment has been substantiated. In about one-third of cases at least one problem related to physical health and emotional and/or cognitive functioning is documented, with the most common concerns being depression or anxiety, followed by learning disability. Ten per cent of maltreated children have a developmen-tal delay. In 40% of cases where child maltreatment is investigated, behavioral concerns are identified. It is important to remember that these child-functioning characteristics are not necessarily causal in the mal-treatment, and may be sequelae of the maltreatment. An American study reported that, in 34 states surveyed,

6.5% of all victims of child maltreatment had a disability, defined as mental retardation, emotional dis-turbance, visual impairment, learning disability, physi-cal disability, behavioral problem, or mediphysi-cal problem.

Household and Caregiver Factors

1. Family structure. Estimates suggest that 43% of mal-treated children live in single-parent families. Nearly one-third of cases involve children living with both biological parents. Approximately 16% of maltreated children live in blended families with a step-parent as caregiver. In cases of sexual abuse, the absence of a biological parent in the household or the presence of a stepfather are particular risk indicators, whereas

Table 1 Definition of child maltreatment

1. Emotional maltreatment

a. Emotional abuse (child has suffered or is at substantial risk of suffering from mental, emotional, or developmental

problems caused by overly hostile, punitive treatment, or habitual or extreme verbal abuse such as threatening, belittling, etc.) b. Nonorganic failure to thrive

c. Emotional neglect (child has suffered or is at substantial risk of suffering from mental, emotional, or developmental problems caused by inadequate nurturance/affection)

d. Exposure to nonintimate violence (between adults other than caregivers) – e.g., child’s father and an acquaintance 2. Exposure to domestic violence

a. Child directly witnesses the violence

b. Child indirectly witnesses the violence (e.g., sees the physical injuries on caregiver the next day or overhears the violence) 3. Neglect

a. Failure to supervise – physical harm (including situations where child was harmed or endangered as a result of caregiver’s actions, e.g., drunk driving with a child, or engaging in dangerous criminal activity with child)

b. Failure to supervise – sexual abuse (caregiver knew or should have known of risk and failed to protect) c. Physical neglect (e.g., inadequate nutrition, clothing, unhygienic or dangerous living conditions)

d. Medical neglect (caregiver does not provide, refuses, or is unavailable/unable to consent to treatment, including dental services) e. Failure to provide psychological/psychiatric treatment (also includes failing to provide treatment for school-related

problems such as learning or behavior problems, infant development problems) f. Permitting criminal behavior (caregiver permits or fails/unable to supervise enough)

g. Abandonment (caregiver died or unable to exercise custodial rights and no provisions made for care of child)

h. Educational neglect (knowingly allows chronic truancy (5 days/month), fails to enroll child, repeatedly keeps child at home) 4. Physical abuse

a. Shake, push, grab, or throw (including pulling, dragging, shaking) b. Hit with hand (e.g., slapping and spanking)

c. Punch, kick, or bite (also hitting with other parts of the body – e.g., elbow, head) d. Hit with object (e.g., stick, belt; throwing an object at a child)

e. Other physical abuse (e.g., choking, stabbing, strangling, shooting, poisoning, abusive use of restraints) 5. Sexual abuse

a. Penetration (penile, digital, or object penetration of vagina or anus) b. Attempted penetration

c. Oral sex d. Fondling

e. Sex talk (proposition, encouragement, or suggestion of a sexual nature; face to face, telephone, written, internet, exposing child to pornographic material)

f. Voyeurism (perpetrator observes child for own sexual gratification) g. Exhibitionism (perpetrator exhibited self for own sexual gratification) h. Exploitation (e.g., pornography, prostitution)

Adapted from Trocme´ N, Fallon B, MacLaurin B,et al. (2005) Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect – 2003: Major findings. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ncfv-cnivf/familyviolence/index.html (accessed on May 2007).

single-parent status is a risk indicator for physical abuse and neglect.

2. Age of primary caregiver. Overall, both male (80%) and female (64%) caregivers who maltreat children tend to be over 30 years of age. The proportion of females under 30 years of age is somewhat increased for neglect and emotional maltreatment.

3. Gender of perpetrator. The majority of nonmentally ill caregivers who cause child maltreatment fatalities are male; however, the younger the maltreated child is, the more likely the perpetrator is to be the child’s mother. Men and women both appear to be equally culpable of nonaccidental injury. Men are over-whelmingly more often the perpetrators in the sexual abuse of both girls and boys (95% and 80% of the time, respectively). Children are twice as likely to be neglected by women than by men, reflecting the fact that women are more often primary caregivers of young children than men.

4. Number of siblings in the household. In65% of cases the maltreated child has at least one other sibling who is living in the household and is also investigated for allegations of child maltreatment.

5. Socioeconomic status. The primary income in families where there is child maltreatment is from full-time employment in the majority of cases (57%); 24% of the time, income is from benefits and/or social assis-tance; and 12% of the time from part-time or sea-sonal work. In cases of neglect, a higher proportion of families obtain their income from benefits or part-time employment.

6. Housing. The majority of children who are maltreated live in rental accommodations (56%), while 32% live in purchased homes, and 1% live in hostels or shelters.

7. Mental illness. American data demonstrate that of caregivers convicted of criminal offenses pertaining to child maltreatment, more than 50% had received psychiatric treatment, and almost one-third have been admitted to hospital for psychiatric treatment. Forty two percent of these mothers were suffering from either major depression or schizophrenia. Another study estimated that 27% of female care-givers and 18% of male carecare-givers were identified as having a mental health impairment.

8. Substance abuse. Approximately 18% of female care-givers and 30% of male carecare-givers abuse alcohol in cases of substantiated child maltreatment. Retro-spective data show that rates of physical and sexual abuse are doubled in cases where caregivers are also reported to have a history of alcohol abuse, with rates markedly increased when both caregivers are sub-stance abusers.

9. Caregiver history of maltreatment as a child. There is controversy and conflicting research evidence as to

whether a childhood history of maltreatment in the caregiver increases the risk for abusive or neglectful behavior as a caregiver. In retrospective studies documenting a link between a history of childhood abuse or neglect and abuse or neglect of one’s children, the link is weak. For example, one study indicated that 25% of abusive female care-givers and 18% of abusive male carecare-givers were maltreated as children; these rates were higher in cases of child neglect and emotional maltreatment. In general,20% of caregivers who were abused as children go on to abuse their own children, whereas 75% of perpetrators of child sexual abuse report having been sexually abused as children.

10. Prior history of criminality. Men who injure their chil-dren more commonly have a history of prior criminal-ity and antisocial personalcriminal-ity traits. One study estimated that 16% were involved in criminal activity. Women in these partnerships often have a psychiatric history, and may be incapable of providing protection to the child.

11. Domestic violence. Approximately 50% of female care-givers who maltreat their children have themselves been victims of domestic violence, including physical, sexual, or verbal assault, in the 6 months prior to the child maltreatment.

Impact of Maltreatment

dissociation, difficulty regulating and expressing negative emotions, low self-esteem, and poor school achievement). There is growing evidence to suggest that emotional abuse and neglect, including exposure to interpersonal violence, can create even more harmful consequences for the child’s functioning and outcome than physical and sexual abuse. Chronic childhood trauma interferes with the capacity to integrate and process sensory, cogni-tive, and emotional information and sets the stage for unfocused and maladaptive responses to subsequent stress. Long-term maltreatment has more pervasive effects than single-incident traumas.

Impact on Brain and Development

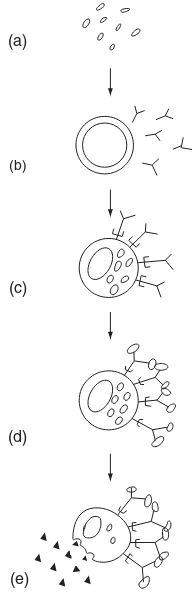

There is considerable evidence to indicate that maltreat-ment experiences in the early years have a profound effect on the developing brain, affecting both acute and long-term development of neuroendocrine, cognitive, and behavioral systems. Alterations in the central neurobiological systems that occur in response to adverse early-life stress lead to increased and abnormal responsiveness to stress, increase the risk of psychopathology in both childhood and adult-hood, and can lead to lifelong psychiatric sequelae such as mood disorders and anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and panic disorder). The association between childhood trauma and the development of mood and anxiety disorders may be mediated by changes in the same neurotransmitter and endocrine systems that modulate the stress response and are implicated in adult mood and anxiety disorders (Figure 1). The impact of early adversity may differentially

affect individuals; some people with a history of severe maltreatment are well adjusted, while others manifest more profound developmental and psychiatric consequences. This likely has to do with complex gene–environment inter-actions which are only beginning to be delineated. One theory underlying the relation between genetic predisposi-tion to major psychiatric disorders and the impact of early traumatic experiences during critical phases of develop-ment is that persistent changes occur in specific neuro-biological systems in response to early stress, which later mediate adaptation to subsequent stressful life events and mood and anxiety symptoms. Specifically, stress has a major impact on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, which is one of the two stress response systems of the body and consists of the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands (Figure 1). The HPA axis activates and coordinates the stress response by receiving and interpret-ing information from other areas of the brain (amygdala and hippocampus) and from the autonomic nervous system. In response to acute situations of stress, a hormonal cas-cade is triggered with the release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus, which stimulates the release of adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland. ACTH then triggers the production of cortisol within the adrenal cortex which is secreted into the blood circulation. Cortisol then provides negative feedback at the level of the hypothalamus, the pituitary, and the hippocampus, thereby shutting off the stress response. This sequence of hormonal responses and negative feedback allows humans to deal with experi-ences of stress in ways that allow them to recover from stressful events.

There is empirical evidence to suggest that following early-life stress, the set point of HPA-axis activity in response to stress is permanently altered so that subsequent adaptation to stressful situations throughout the lifespan may be affected. In other words, infants who are maltreated and traumatized might later react with overwhelming stress to innocuous or mildly stressful events. There is also evidence to suggest that early-life stress is related to persistent sensitization of pituitary–adrenal and auto-nomic stress responses, most likely caused by CRH hyper-secretion, and may increase risk for psychopathology during adulthood. For example, research shows the impli-cation of the CRH system in adult mood and anxiety disorders. This is because the HPA axis is involved not only in the stress response but also in the development of mood and anxiety disorders. Dysregulation of the CRH and the other downstream hormones (ACTH and cortisol; Figure 1) may explain the symptoms of increased vigi-lance and enhanced startle response observed in patients with anxiety disorders, such as PTSD, and may in part explain the high incidence of comorbid anxiety and mood disorders. It is important to note that most clinical studies evaluating the impact of childhood trauma on the brain

Stress

Brain

Negative feedback

Pituitary gland

Adrenal gland Hippocampus

Hypothalamus CRH

ACTH

Cortisol

Figure 1 The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis.

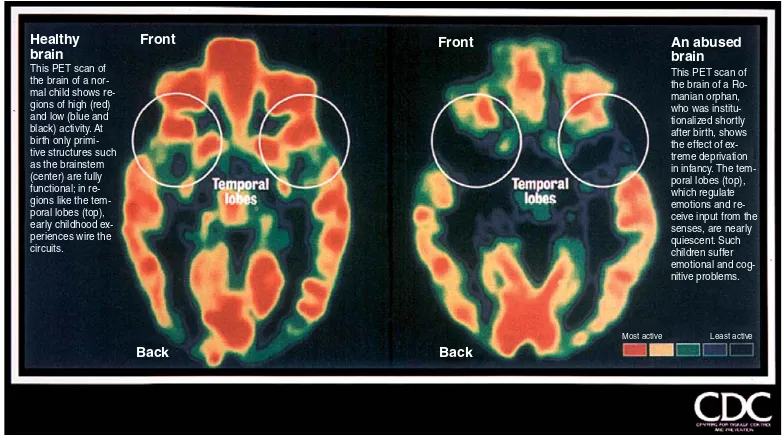

have been conducted in adults or children who have a his-tory of physical or sexual abuse. However, different results in these various studies suggest that the effects of early-life stress may be variable and influenced by numerous factors. When the HPA axis is overactivated over long periods (e.g., when an infant is repeatedly stressed by experiences of maltreatment), it becomes dysregulated and creates the production of stress hormones at levels that can be harm-ful, particularly to a developing brain. Some structural brain changes have been documented in individuals who are victims of child maltreatment, specifically in the hip-pocampus, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala. Recent data suggest that CRH hypersecretion itself (leading to high levels of cortisol) may be one causative factor in these structural alterations. The stress hormone cortisol pre-pares us to withstand threatening or stressful events. However, too much cortisol for too long is detrimental to the brain and linked to marked changes in brain activity and structures. Multiple brain regions may be affected by chronic and frequent high levels of cortisol. Specific areas of the brain that are negatively affected by sustained elevations in cortisol over time include:

1. The hippocampus, the brain structure involved in learning and explicit memory (remembering where one left one’s keys is an example of explicit memory); a shrinkage of the hippocampus has been documented in adults who experienced PTSD and presumably produced high levels of cortisol at the time of trauma. 2. The anterior cingulate gyrus, the brain structure involved in selective attention; disruption in this may lead to difficulty focusing attention and inhibiting inappropriate actions.

3. The amygdala, the brain structure involved in the pro-cessing of frightening and negative events; the affected individual becomes more sensitive to negative emotions and is more likely to produce a hormonal stress reaction in situations of perceived threat.

4. The prefrontal cortex is the brain structure that is sensitive to information about the social environment and social partners; affected individuals may find it difficult to act appropriately in social situations (espe-cially for children; however, this area is also developing until late adolescence and early adulthood).

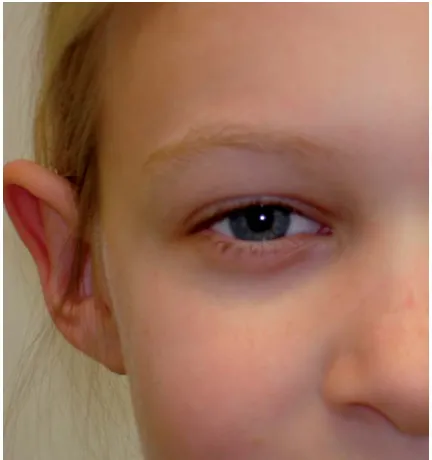

5. The cerebral cortex and corpus callosum. Studies have shown lower intracranial volumes in individuals with PTSD compared to carefully matched controls, in addi-tion to smaller volumes of the corpus callosum (and hippocampus). More global effects include intelligence, which was negatively correlated with duration of mal-treatment, and intracranial volume which was correlated with age of onset of maltreatment (Figure 2).

Recent data suggest that effects of exposure to increased levels of maternal cortisol, in cases where pregnant women have PTSD, can be observed very early in the life of the offspring and underscore the relevance of in utero contributors to putative biological risk for PTSD. Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that early trauma can be toxic to the developing brain.

Neuroimaging studies have documented significant neurobiological changes in three specific areas of the brain of individuals with PTSD compared to individuals without PTSD: the hippocampus (responsible for some aspects of memory), the amygdala (responsible for the emotional and somatic contents of memories), and the

Healthy Front Front

Back

Most active Least active Back

An abused brain This PET scan of the brain of a Ro-manian orphan, who was institu-tionalized shortly after birth, shows the effect of ex-treme deprivation in infancy. The tem-poral lobes (top), which regulate emotions and re-ceive input from the senses, are nearly quiescent. Such children suffer emotional and cog-nitive problems. This PET scan of

the brain of a nor-mal child shows re-gions of high (red) and low (blue and black) activity. At birth only primi-tive structures such as the brainstem (center) are fully functional; in re-gions like the tem-poral lobes (top), early childhood ex-periences wire the circuits. brain

Figure 2 Effects of maltreatment on brain structures. Reproduced from the CDC website.

medial frontal cortex (responsible for the modulation of the cognitive control of the anxiety response and is probably essential for habituation in normative stress reactions). A current hypothesis attributes the hallmark symptoms of PTSD, exaggerated startle response and flashbacks, to the failure of the hippocampus and medial frontal cortex to dampen the exaggerated symptoms of arousal and distress that are mediated through the amyg-dala, in response to reminders of the traumatic event.

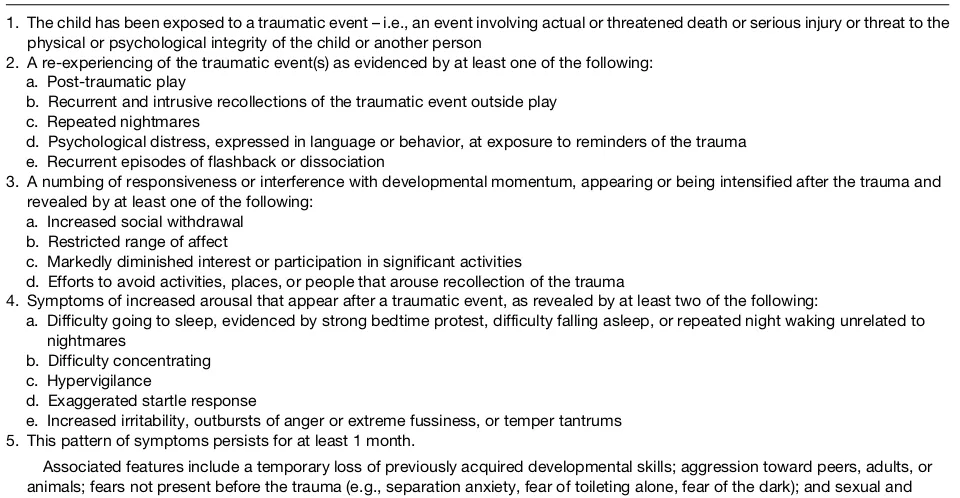

Impact on Behavior

The internal neuroendocrine and neurobiological changes associated with early exposure to maltreatment are often ‘translated’ into observable behavioral symptoms. For example, a subgroup of maltreated infants and young children can suffer from PTSD (Table 2lists symptoms of PTSD in infants). PTSD is important to recognize in infants exposed to violence and maltreatment as its symptoms are not likely to resolve spontaneously and the associated risk for long-term adverse outcomes if left untreated is high. However, it is important to recognize that not all infants exposed to a traumatic event will develop PTSD and that some infants who develop PTSD will resolve their PTSD symptoms – for example, with appropriate intervention, without long-term consequences.

While PTSD is a serious sequela of early exposure to violence and maltreatment that requires treatment, clinicians must be aware that a group of infants exposed to traumatic events, especially infants who are chroni-cally traumatized by their attachment figures’ abusive and/or neglectful caregiving, may not display prominent symptoms of PTSD. Instead, infants and toddlers who have endured repeated maltreatment, complex trauma, exposure to violence, and other chronic forms of maltreat-ment often do not meet criteria for PTSD but experience developmental delays across a broad spectrum, including physical, cognitive, affective, language, motor, and social-ization skills. As a result of their multiple developmental delays, they tend to display complex disturbances with a variety of often fluctuating presentations that are quali-tatively different from the clinical presentation of an infant with PTSD. The lack of capacity for emotional self-regulation is probably the most striking feature of infants who have experienced chronic and complex trauma and may contribute to the various associated symptoms which can be grouped into five major categories:

1. Intrapersonal thoughts/self-concept, such as lack of a continuous, predictable sense of self, a poor sense of separatedness, disturbances of body image, low self-esteem (and related behaviors), shame and guilt, and negative life view.

Table 2 Diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder in infants and young children

1. The child has been exposed to a traumatic event – i.e., an event involving actual or threatened death or serious injury or threat to the physical or psychological integrity of the child or another person

2. A re-experiencing of the traumatic event(s) as evidenced by at least one of the following: a. Post-traumatic play

b. Recurrent and intrusive recollections of the traumatic event outside play c. Repeated nightmares

d. Psychological distress, expressed in language or behavior, at exposure to reminders of the trauma e. Recurrent episodes of flashback or dissociation

3. A numbing of responsiveness or interference with developmental momentum, appearing or being intensified after the trauma and revealed by at least one of the following:

a. Increased social withdrawal b. Restricted range of affect

c. Markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities

d. Efforts to avoid activities, places, or people that arouse recollection of the trauma

4. Symptoms of increased arousal that appear after a traumatic event, as revealed by at least two of the following:

a. Difficulty going to sleep, evidenced by strong bedtime protest, difficulty falling asleep, or repeated night waking unrelated to nightmares

b. Difficulty concentrating c. Hypervigilance

d. Exaggerated startle response

e. Increased irritability, outbursts of anger or extreme fussiness, or temper tantrums 5. This pattern of symptoms persists for at least 1 month.

Associated features include a temporary loss of previously acquired developmental skills; aggression toward peers, adults, or animals; fears not present before the trauma (e.g., separation anxiety, fear of toileting alone, fear of the dark); and sexual and aggressive behaviors inappropriate for a child’s age.

Adapted from The DC:0–3R Revision Task Force (2005)DC:0–3R – Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood, Rev. edn. Arlington, VA: Zero to Three Press.

2. Emotional health, such as dissociative experiences (e.g., distinct alterations in states of consciousness, amnesia, depersonalization and derealization, impaired memory for state-based events); problems with affect regulation (e.g., difficulty with emotional self-regulation, difficulty labeling and expressing feelings, problems knowing and describing internal states, and difficulty communicating wishes and needs); impaired behavioral control (e.g., poor modulation of impulses, self-destructive behavior, aggression toward others, pathological self-soothing behavior, sleep and eating disturbances, substance abuse, excessive compliance, oppositional behavior/ difficulty understanding and complying with rules, re-enactment of trauma in behavior or play with sexual, aggressive themes); anxiety disorders (e.g., separation anxiety disorder, PTSD); mood disorders; suicidal thoughts (e.g., children exposed to domestic violence have a six times higher likelihood of attempting suicide compared to children who did not grow up in violent homes); personality disorder (e.g., borderline, narcissis-tic, paranoid, obsessive–compulsive).

3. Interpersonal relationships (e.g., disorganized infant– caregiver attachment; problems with boundaries; distrust and suspiciousness; social isolation), interper-sonal difficulties (low social competency, difficulty attuning to other people’s emotional states, decreased capacity for empathy/sympathy for others, difficulty with perspective taking); noncompliance; oppositional defiant disorder; disruptive or antisocial behaviors; delinquency/criminality (74% greater chance of com-mitting crimes against a person); sexual maladjustment (abuse toward dating partner; 24% greater chance of committing sexual assault crimes; sexual dysfunctions in women); dependency.

4. Learning/cognition (e.g., difficulties with object con-stancy, attention regulation, focusing on and completing tasks, executive functioning, planning and anticipating, processing novel information, understanding responsi-bility; lack of sustained curiosity); learning difficulties or low academic achievement; problems with language development and orientation in time and space; impaired moral reasoning.

5. Physical health/biology (e.g., increased medical pro-blems or complaints across the lifespan such as failure to thrive, asthma, skin problems, pseudoseizures, soma-tization, pelvic pain, autoimmune disorders; high mor-tality; sensorimotor developmental problems; analgesia; problems with coordination, balance, muscle tone).

Assessment

Maltreated infants represent a heterogeneous population. Maltreatment refers to a range of abusive/neglectful caregiver behavior that varies along a number of different

dimensions (e.g., severity, duration) and, as a result, the outcomes for these infants are not uniform or universal. Some infants may be asymptomatic, while others present as being significantly impacted by their adverse experi-ences. A comprehensive clinical assessment helps to determine the unique impact of maltreatment on the individual infant. Because of potential police, child pro-tection, and court involvement, assessments need to be forensically sound. Various published guidelines summa-rize the domains to be addressed when assessing the impact of child maltreatment and determining the most appropriate treatment recommendations. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has pub-lished several separate assessment guidelines depending on the age of the child, the presenting problem, and the focus of the assessment. For example, the following assess-ment guidelines would be relevant when assessing con-cerns related to child maltreatment: the assessment of infants and toddlers, the forensic evaluation for children and adolescents who may have been sexually abused, the assessment of PTSD, the assessment of sexually abusive children, and the assessment of reactive attachment disor-der. The American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children has also published guidelines, including guidelines for the assessment of suspected psychological treatment in children and adolescents. Finally, the Zero to Three/National Center for Clinical Infant Programs also provides guidelines for the assessment of very young children.

These various guidelines generally recommend a multidimensional approach to gathering information, including obtaining information from multiple sources (e.g., caregivers, child, daycare or school, child protection workers, police) and using a variety of assessment methods (e.g., clinical interview, structured and semistructured diagnostic interviews, questionnaires, observation). Eval-uation of the young child’s strengths and vulnerabilities within the various overlapping domains of development (e.g., biological, social, emotional, behavioral, cognitive) is essential. This information must then be placed within the child’s environmental context (e.g., caregiver–child relationship, family systems and beliefs, socioeconomic circumstances).

Interviews with the child’s caregivers allow the asses-sor to gather information about the developmental history of the child to determine the child’s overall level of functioning before and after the child’s experiences of maltreatment. It also allows the assessor to gather infor-mation about the child’s caregivers (including trauma history, mental health history, substance abuse history, and environmental stressors such as poverty, exposure to domestic or community violence) in order to determine the caregivers’ strengths and vulnerabilities and their abil-ity to support the child and participate in recommended interventions.

A direct interview with the very young child may not be possible due to language limitations and cognitive immaturity. Even a young child, however, may be able to provide valuable information about his or her experi-ences. Information may be gathered from a younger child during a play-based interaction with the assessor using materials appropriate for this age group (e.g., age appro-priate toys representing aspects of daily life), and/or direct observation of the child interacting with significant others (e.g., caregivers, teachers, peers).

Collateral information provides the assessor with information about the nature and history of the child and family’s involvement with other services and agencies (e.g., mental health, child protective services, education). It is important to gather information about previous child welfare involvement to determine the extent of previ-ously reported child maltreatment. This provides infor-mation about the chronic nature of the maltreatment, and the child and family’s response to previous interven-tion. Interviews with the child’s siblings and other family members (e.g., grandparents) may yield additional infor-mation. The main goals of gathering this information are to determine the child’s level of functioning before and after the incident(s) of maltreatment, to determine the presence of any specific psychiatric disorder (e.g., PTSD;Table 2), and to develop an appropriate treatment plan for the child and family.

During the first 3 years of life, the quality of the caregiver–child relationship is of primary importance, and therefore is often the central focus of both assessment and intervention. Components of the caregiver–child relation-ship to be assessed include both the observable interactions between child and caregiver during various structured and unstructured activities (e.g., play, feeding, limit setting) and the caregivers’ perceptions and subjective experience of the child and their relationship with the child (e.g., attributions about the child’s behavior, importance of their role as caregivers). In addition, an assessment of the quality of the child’s attachment relationships with his or her caregivers should be completed. Structured protocols should be used to assess the internal and external aspects of the caregiver–child relationship. Structured protocols can provide valuable information about areas of strength and vulnerability in the caregiver–child relationship which can be targeted during treatment.

The assessment should focus on both the child’s general functioning and any maltreatment-specific issues. The assessment of the child’s general functioning is informed by the various overlapping domains of development and the salient developmental tasks and challenges for a child at a particular age and stage of development. The various domains of functioning include:

1. Neurophysiological regulation (e.g., eating, sleeping, and capacity to self-soothe).

2. Affect regulation (e.g., accurate identification of inter-nal emotiointer-nal states, differentiation, interpretation, and application of appropriate emotional labels; safe emotional expression; and ability to modulate/regulate internal experiences). When children have an impaired capacity to self-regulate and self-soothe, they may present as emotionally labile, often in response to minor stressors.

3. Social skills and relational difficulties.

4. Emotional – including anxiety, mood, and attachment (separation anxiety, establishing a secure attachment relationship); self-esteem, self-efficacy.

5. Behavioral regulation – undercontrolled (e.g., aggres-sive, controlling, oppositional) or overcontrolled (e.g., compulsive compliance) behavioral patterns.

6. Cognitive/language development (e.g., expressive/ receptive language, problem-solving, attention, abstract reasoning, executive function skills).

7. Temperament and constitutional characteristics. The assessment of maltreatment-specific issues involves gathering details about each incident of maltreatment that the child has experienced. Relevant information includes the frequency, severity, and chronic nature of all incidents of maltreatment; the nature of the relation-ship between the child and the individual(s) who is/are maltreating the child; and the family/situational context in which the abuse has occurred. Gaining an under-standing of the relationship between each of these factors assists in determining an appropriate intervention.

The response of the nonoffending caregiver(s) to the child’s disclosure of maltreatment is one of the strongest predictors of outcome for young children. The level of caregiver support has a significant impact on the child’s level of functioning, and therefore is an important aspect of assessment, and a target for intervention. The presence of a supportive primary caregiver, or a supportive rela-tionship with another important adult, is associated with decreased levels of distress and lower levels of behavior problems. The assessment of the caregiver’s support involves determining the caregiver’s level of belief in and validation of the child’s experience, the caregiver’s emotional availability for the child (e.g., caregiver’s abil-ity to experience a range of emotions, to label the child’s emotional experiences accurately, to tolerate the child’s distress), the caregiver’s own level of distress, and how the caregiver is managing his or her own emotional response.

Treatment

address the unique needs of the child and family. Some treatments target specific individuals (e.g., child, caregiver, family, caregiver–child dyad), specific issues (e.g., anger management, caregiving or parenting skills, addressing mental health concerns, child behavior management), or vary according to treatment modality (e.g., individual, family, group). When children are very young, however, caregivers play a particularly significant role in the child’s assessment, treatment, and recovery. Although inter-ventions vary according to the unique needs of the child and family, and may specifically target the child, caregivers, family, or environment, or various targets simultaneously, all forms of treatment for maltreated infants and their families have three essential, basic components in common, including:

1. Establishing a sense of safety by providing reassurance to the child, and in some situations actually creating a safe environment by removing the child from an unsafe situation, or removing the individuals who are creating an unsafe and/or high-risk situation for the child. The treatment process is hindered if the child experiences repeated exposure to unsafe and stressful situations (e.g., remaining in a home where there is ongoing exposure to domestic violence).

2. Addressing issues of engagement/motivation, as many caregivers involved with the child protection system are obligated to attend treatment rather than seeking treatment voluntarily.

3. Addressing practical issues that may create obstacles to attending treatment (e.g., child-care, transportation, provision of snacks, financial assistance).

Other components of interventions may then focus specifically on helping the child and/or the caregiver in the following ways:

1. Helping the ‘child’ to:

. Reduce the intensity of affect (e.g., fear, anger) and to regulate their affect, as experiencing maltreatment is often associated with affective dysregulation. . Develop a coherent narrative (the complexity of

the narrative will vary depending on the age of the child) of their negative experiences, and to integrate these experiences at a level appropriate to the child’s developmental stage. An aspect of this process may also involve the therapist challenging distorted cog-nitions associated with the negative experiences (e.g., guilt, responsibility) with children who are old enough.

2. Helping ‘nonmaltreating caregivers’ to:

. Be emotionally available and able to respond em-pathically to the needs of the child. This may in-clude psychoeducation about outcomes associated with different types of maltreatment and helping

caregivers link specific symptoms to the child’s adverse experiences, helping caregivers manage the child’s symptoms within the home environment and develop effective behavior management strate-gies, and assisting caregivers to negotiate the child welfare and legal systems. This may also involve referring the caregiver for individual treatment as many nonoffending caregivers may also have expe-rienced trauma or violence within the home. 3. Helping the ‘child and caregiver(s)’ to:

. Deal with the negative sequelae of the maltreat-ment (e.g., manage the child’s behavioral distur-bance, developmental delay, adjusting to a change in residence, separation from caregivers, financial hardship). Referral for specialized assessment may be necessary (e.g., occupational therapy, speech and language pathology).

. Address both abuse-specific (e.g., PTSD) and gen-eral psychopathology (e.g., depression, disrupted behavior) in the child and/or caregivers.

In recent years there has been an increase in the research exploring the efficacy of a number of different interventions that target maltreated children and their families and incorporate the aforementioned components of intervention. In 2003, the National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center published a report sum-marizing the review of several different interventions that have some level of empirical support. Several of these interventions are now considered ‘best practice’ when working with maltreated children and their families. However, these interventions have not been validated for use in children under 3 years of age.

The intervention that has received the highest rating and the most empirical support is trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT). This intervention is designed for children as young as 3 years who have exp-erienced sexual abuse, and who are displaying symptoms of PTSD and associated mental health problems (e.g., anxiety, depression, inappropriate sexual behaviors). The treatment model can be adapted to the developmental level of the child. TF-CBT is based on learning and cognitive theories, and is designed to reduce children’s negative behavior and emotional responses, and to identify and correct maladap-tive attributions and beliefs related to the sexual abuse. This intervention also involves providing support and teaching skills to the nonoffending caregiver(s) to enhance their coping and their ability to respond to the child’s needs. No comparable intervention has been validated for use with children under 3 years of age.

the common sequelae for children who have experienced physical abuse (e.g., aggression, poor social competence and relationship skills, trauma-related symptoms). The intervention is comprised of primary caregiver, child, and family systems components and is appropriate for mal-treated infants and their families.

The third intervention that received a high rating is parent–child interaction therapy (PCIT). This interven-tion is used with physically abusive caregivers who have children as young as 4 years. PCIT is a caregiver–child relationship intervention that focuses on several goals including improving parenting skills, decreasing child behavior problems, and improving the quality of the caregiver–child relationship. Specifically, the intervention addresses the coercive relationship that has developed between the caregiver and child and pattern of parent response to the child (e.g., high rates of negative interaction, low rates of positive interaction, ineffective parenting stra-tegies, over-reliance on punishment). It also addresses the child’s behavioral difficulties (e.g., aggression, defiance, noncompliance, and resistance in response to caregivers’ requests). Although there are no published reports of its efficacy in treating infants, there is clinical evidence that PCIT may be appropriate for maltreated infants and their families.

Lieberman and Van Horn’s (2000) child–parent psy-chotherapy for young children who have been exposed to family violence is a relationship-based treatment model that has several basic premises. These include the prem-ise that the child–caregiver attachment relationship is of paramount importance as the main organizer of children’s responses to danger and safety within the first 5 years of life, that emotional and behavioral problems in young children need to be addressed within the context of the child’s primary attachment relationships, that risk factors during the first 5 years of life operate within the context of transactions between the child and the child’s ecological environment (e.g., family, neighborhood, community), and that interpersonal violence is a traumatic stressor that has specific adverse effects on those who witness and/or experience it. Although this intervention has not yet received the empirical support of the previously described interventions, it is based on sound theory, and is an accepted clinical approach used by experts in the field. Research exploring the efficacy of this intervention would provide additional support for its use.

Conclusion

Maltreatment during infancy, a formative period of both physical and psychological growth, presents serious chal-lenges to development. Such disruptions continue to impact many maltreated infants and produce deleterious

short- and long-term effects on the infant’s brain and behavior. Maltreated infants require early identification along with appropriate assessment and interventions. The aim and ongoing task, at both a policy and clinical practice level, involves the prevention of serious, negative long-term sequelae of maltreatment.

See also: Attachment; Brain Development; Emotion Regulation; Endocrine System; Mental Health, Infant; Mortality, Infant; Nutrition and Diet; Risk and Resil-ience; Safety and Childproofing; Stress and Coping; Temperament.

Suggested Readings

Glaser D (2000) Child abuse and neglect and the brain – a review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry41: 97–116. Kaplan SJ, Pelcovitz D, and Labruna V (1999) Child and adolescent

abuse and neglect research: A review of the past 10 years. Part 1: Physical and emotional abuse and neglect.Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry38: 1214–1222.

Larrieu JA and Zeanah CH (2004) Treating parent–infant relationships in the context of maltreatment: An integrated systems approach. In: Sameroff AJ McDonough SC, and Rosenblum KL (eds.)Treating Parent–Infant Relationship Problems – Strategies for Interventions, pp. 243–267. New York: Guiford Press.

Lieberman AF and Van Horn P (2000)Don’t Hit My Mommy! A Manual for Child–Parent Psychotherapy with Young Witnesses of Family Violence.Washington DC: Zero to Three Press.

Nemeroff CB (2004) Neurobiological consequences of childhood trauma.Journal of Clinical Psychiatry65(supplement 1): 18–28. Osofsky J (ed.) (2004)Young Children and Trauma: Intervention and

Treatment.New York: Guilford Press.

Perry BD (2004)Maltreatment and the Developing Child: How Early Childhood Experience Shapes Child and Culture. The Margaret McCain Lecture Series.http://www.lfcc.on.ca (accessed May 2007).

Scheeringa MS and Gaensbauer TJ (2000) Posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Zeanah CH (ed.)Handbook of Infant Mental Health pp. 369–381. New York: Guilford Press.

The DC:0–3R Revision Task Force (2005)DC:0–3R – Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood,Rev. edn. Arlington, VA: Zero to Three Press.

Trocme´ N, Fallon B, MacLaurin B,et al.(2005) Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect – 2003: Major findings. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ncfv-cnivf/familyviolence/index.html (accessed on May 2007).

Relevant Websites

http://www.nctsn.org– National Child Traumatic Stress Network. http://www.musc.edu/ncvc– National Crime Victims Research and

Treatment Center –Child Physical and Sexual Abuse: Guidelines for Treatment (Revised Report: April 25, 2004).

http://www.apsac.org– Practice guidelines from the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children.

http://www.aacap.org– Practice parameters from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry pertaining to the psychiatric assessment of infants and toddlers (0–36 months).