What Do Educational Credentials Signal and Why Do

Employers Value Credentials?

Jeremy Arkes

The CNA Corporation, 4401 Ford Avenue, Alexandria, VA 22302-8268, USA

Received 7 June 1996; accepted 9 September 1997

Abstract

This paper examines whether employers can infer information about workers’ pre-college abilities from the college credentials they acquire and whether employers value the attainment of credentials because credentials signal these abilities. I find that a high school diploma, college attendance, a bachelor’s degree and a graduate degree signal higher pre-college abilities that are reflected in scores from tests administered to respondents in the NLSY. However, an associate’s degree does not. Estimating a sorting model of wage determination, the results indicate that employers do value the attainment of a bachelor’s degree in part because it signals these pre-college abilities. The coefficient estimates on an associate’s degree and a bachelor’s degree remain statistically significant after controlling for ability. This indi-cates that these degrees mark other attributes that employers find worthwhile, perhaps unobserved ability such as motivation and perseverance. [JEL J31]1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

In most European and Asian countries, high school students take national achievement tests, which are often used for college admission and job screening. While such tests are not used in the United States for job screening, employers before 1971 often administered their own achievement tests, but the 1971 Supreme Court decision in Griggs vs Duke Power Company1held that employers

who base hiring decisions on such achievement tests for which minorities or women perform worse than white males must prove that test scores are related to job per-formance for all groups of workers. This decision essen-tially made the use of intelligence tests too costly for most small- and medium-sized firms (Bishop, 1992).2In

1401 U.S. 424.

2In the 1989 decision for Wards Cove Packing Co. vs Antonio (490 U.S. 642), the Supreme Court increased the bur-den on the plaintiff (the adversely affected worker or job applicant) and decreased the burden on the defendant (the employer). Still, the potential for a lawsuit remained.

0272-7757/98/$ - see front matter1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. PII: S 0 2 7 2 - 7 7 5 7 ( 9 8 ) 0 0 0 2 4 - 7

place of such tests, employers can make inferences about workers’ abilities by noticing associations for experi-enced workers between educational attainment and the abilities that they would normally measure with intelli-gence tests. Thus, employers may hire and pay higher wages to more educated workers not only because edu-cation makes workers more productive, but also because education signals certain traits or abilities that employers find worthwhile.

of the policies that make it difficult for employers to administer ability tests to prospective employees.

One other contribution of this paper is that it identifies another educational credential not ordinarily considered as one, namely college attendance. By attending college, a person arguably displays the motivation to learn and to improve himself, thereby distinguishing himself from someone who only acquires a high school diploma. In addition, it may show that some institution that may have access to his cognitive ability test scores has deemed this person capable of completing its academic program.

For an ability measure, I use the Armed Forces Quali-fication Test, which was administered to the respondents in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY). The test measures a wide range of abilities. It is important in sorting models to consider pre-existing abilities (or pre-college abilities in this case). Otherwise, it would be difficult to separate the abilities signaled by college from the productive skills acquired in college. Thus, I consider a sample from the NLSY of respondents who were no older than 18 and had not attended college at the time they took the ability test. The results show statistically significant partial associations between pre-college ability and a high school diploma, pre-college attend-ance, a bachelor’s degree and an advanced degree, but not an associate’s degree.

Given that credentials signal certain abilities, employers should value the attainment of credentials based on how much new information is conveyed by cre-dentials about workers’ abilities and how much they value the abilities. For instance, suppose that a bach-elor’s degree signals three traits: competent mathemat-ical abilities, high motivation and good memory. Employers may value only mathematical abilities and motivation. Furthermore, employers may already have an adequate sense of the worker’s mathematical abilities by observing school transcripts. Thus, even though a bach-elor’s degree may signal good memory and high math-ematical abilities, employers would value the degree because it signals motivation, and not because it signals the other traits.

To determine the extent to which employers value the attainment of credentials for signaling pre-college abili-ties, I take it as given that firms reward educational attainment in part because a higher education signals qualities that are initially unobservable to employers and that indicate greater productivity. Thus, I employ a sort-ing model of wage determination, which allows edu-cation to have an effect on productivity, as well as serv-ing as a signal of pre-existserv-ing ability (Weiss, 1995). The results suggest that employers value and reward a bach-elor’s degree in part because it signals abilities reflected in the pre-college ability scores. Results for the other credentials are inconclusive due to large standard errors.

2. Previous work and a new interpretation of wage premiums for credentials

In the Spence (1974) signaling model, individuals enter the labor force with different levels of productivity. Since employers cannot initially discern the true pro-ductivity of workers and since acquiring this information may be costly, employers rely on market signals of pro-ductivity, such as a bachelor’s degree, to determine workers’ wages. The more-productive individuals can distinguish themselves from less-productive individuals by completing a bachelor’s degree or obtaining some other credential, thereby signaling their higher pro-ductivity. In a sorting equilibrium, employers’ prior beliefs on the ability or productivity differences across educational levels are confirmed by the ability and pro-ductivity distributions of new workers.

In light of the signaling or sorting model, several authors have attempted to estimate the wage premiums associated with certain degrees: in particular a high school diploma, an associate’s degree, a bachelor’s degree and an advanced degree (Hungerford and Solon, 1987; Belman and Heywood, 1991; Frazis, 1993; Hey-wood, 1994; Grubb, 1993; Kane and Rouse, 1995). They include years of education completed and credentials earned in wage regressions. The coefficient estimate on a credential represents the wage difference between cre-dentialled and noncrecre-dentialled workers, holding years of education and other factors constant. If wages are pro-portional to expected productivity, then the coefficient estimate on a credential indicates the productivity differ-ences between credentialled and noncredentialled work-ers.

interpret the presence of attributes that are unobservable to the firm and correlated with productivity and edu-cation. In a human capital model, if the researcher cannot measure or does not include some ability-type measure that is correlated with educational attainment and pro-ductivity, then the estimated returns to education would be biased, but a sorting model should intentionally omit attributes that are unobservable to the firm and correlated with education and productivity. The premise is that employers cannot observe abilities in potential and new employees, but can only infer workers’ skills by observ-ing their credentials. Thus, part of the return to education is attributable to education signaling the attributes that employers find worthwhile, some of which are unobserv-able to the employers. To include measures of these attri-butes in a wage regression would result in a downwardly biased measure of the wage premium for credentials. Therefore, when estimating the wage premiums associa-ted with credentials, it is important to indicate whether one is assuming that a sorting model or a human capital model applies in order to properly interpret the estimates. An important point from the discussion above is that in a sorting framework, controlling for abilities that are unobservable to employers would result in an estimated wage premium for credentials that is meaningless (by itself) since it no longer represents the difference in pro-ductivity between the credentialled and noncredentialled workers. In fact, if a researcher were to control for the complete set of abilities that the credentials signal, then the estimated wage premiums for the credentials should be zero. However, the differences in the estimates when controlling and not controlling for abilities are informa-tive since they identify the portions of perceived pro-ductivity differences between credentialled and noncre-dentialled workers attributable to credentials signaling these abilities.

Frazis (1993) controls for ability — observed ability and unobserved ability calculated from an ordered pro-bit — to determine if selection bias explains the college degree effect. He finds that including ability measures has little effect on the college degree coefficient estimate. In addition, he interacts the ability measures with years of college to address a hypothesis of Chiswick (1973), that the degree effect results from the fact that those who are receiving more benefits from education are more likely to stay in school and receive their degrees. Again, Frazis finds no evidence supporting this hypothesis.

This analysis advances Frazis’ work in several ways. First, Frazis uses mean values to proxy for measurable abilities for respondents who have missing ability data, who comprise 27% of the sample. His method could dampen the explanatory power of these ability measures. In contrast, I exclude these workers since my interest is in whether credentials signal these abilities. Second, whereas Frazis considers a sample of 25-year olds, many of whom had not completed their schooling, this analysis

uses a sample of workers aged 28–30. Thus, it is more likely that the respondents in my sample are finished with school. Third, while Frazis only focuses on the bachelor’s degree, I examine the high school diploma, college attendance, the associate’s degree and the advanced degree credentials as well. Finally, I consider the initial stage of the sorting model, analyzing what abilities credentials signal.

3. Data

The sample consists of males drawn from the 1993 wave of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. The NLSY began with 12 686 14- to 22-year old individuals in early 1979, 6403 of whom are males.

Weiss (1995) states that in sorting models, “schooling is correlated with differences among workers that were present before the schooling choices were made.” If ability were measured during or after one’s education, then one could not separate the abilities signaled by edu-cation from the productive skills learned in school. For the NLSY, however, individuals were aged 15–24 when they took the test in July 1980. In light of Weiss’ state-ment, I restrict the sample to respondents who were aged 15–18 when they took the test in July 1980, and who had not attended college at the time. Thus, the measure of ability is pre-college.

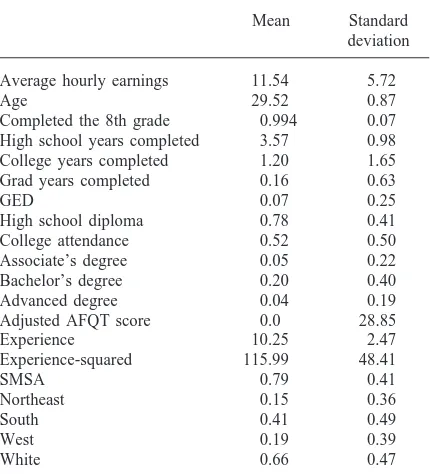

Additional criteria to be in the sample are that the respondents must have been working at the time of the interview, had an average hourly wage rate greater than one-half the minimum wage at the time and less than $60, had not been enrolled in school, had not been self-employed, and had taken the ability tests. The respon-dents in the sample were aged mostly 28–30 in 1993. The final sample size is 1064 individuals. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the sample.

Of the original sample, 94% took the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB). The tests, along with what they measure, are as follows (Bishop, 1992):

1. general science — knowledge of the physical and bio-logical sciences;

2. arithmetic reasoning — ability to solve arithmetic word problems;

3. word knowledge — ability to select the correct mean-ing of words presented in context and to identify the best synonym for a given word;

4. paragraph comprehension — ability to obtain infor-mation from written passages;

5. numerical operations — ability to perform arithmetic computations in a speeded context;

6. coding speed — ability to use a key in assigning code numbers to words in a speeded context;

Table 1

Descriptive statistics. Number of observations51064

Mean Standard deviation

Average hourly earnings 11.54 5.72

Age 29.52 0.87

Completed the 8th grade 0.994 0.07 High school years completed 3.57 0.98 College years completed 1.20 1.65

Grad years completed 0.16 0.63

GED 0.07 0.25

High school diploma 0.78 0.41

College attendance 0.52 0.50

Associate’s degree 0.05 0.22

Bachelor’s degree 0.20 0.40

Advanced degree 0.04 0.19

Adjusted AFQT score 0.0 28.85

Experience 10.25 2.47

8. mathematics knowledge — knowledge of high school mathematics principles;

9. mechanical comprehension — knowledge of mechan-ical and physmechan-ical principles and ability to visualize how illustrated objects work; and

10. electronics information — knowledge of electricity and electronics.

The scores from four of the 10 tests in the ASVAB — arithmetic reasoning, word knowledge, paragraph com-prehension and numerical operations — constitute the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) score.3In this

analysis, I consider the AFQT score as a comprehensive ability measure since it is a commonly used measure of ability and is found to have high correlations — with a median correlation of 0.38 — with job performance in 23 military occupations (Widgor and Green, 1991). Since age affects competency in these areas, I use age-corrected test scores, which are the residuals from a regression of the test scores on age dummy variables (Neal and Johnson, 1994). The scores are then transfor-med so that each point represents one percentile in the sample.

The educational data come from self-reported attain-ment. Included as indicators of the productive skills acquired in school are the number of high school years

3The AFQT score is the sum of the arithmetic reasoning score, word knowledge score, paragraph comprehension score and one-half the numerical operations score.

(ranging from 0 to 4), college years and post-graduate years completed.4,5 The educational credentials are a

high school diploma, college attendance (without neces-sarily completing a year of college), an associate’s degree, a bachelor’s degree and an advanced degree. If a person has both an associate’s and a bachelor’s degree, the associate’s degree is disregarded because employers would probably be more interested in the abilities that a bachelor’s degree signals than in those marked by an associate’s degree. Also, employers probably would not consider a person with both degrees to be more pro-ductive than one with only a bachelor’s degree.

Finally, this analysis may suffer from attrition bias. The 1993 interview for the NLSY includes 78% of the 14-, 15- and 16-year olds from the 1979 survey who took the ASVAB exam in July 1980 and who had not entered college by early 1980. This analysis assumes that attrition is unrelated to the wages respondents earn or the education they attain. To the extent that this is not true, the results may be biased.6

4. What pre-college abilities do educational credentials signal?

To determine what skills credentials signal, I perform regressions of the ability test scores on educational lev-els. The regressions indicate whether employers can infer any information about workers’ pre-college abilities from the credentials they acquire, over and above what employers learn from workers’ years of education com-pleted. The conditional expectation of a worker’s age-adjusted pre-college ability is modeled as a linear func-tion of his educafunc-tion and race as follows:

E[A/S,C,R]5g01Sg11Cg21Rg3 (1)

where A is an ability measure, S is a vector of measures

4I calculate post-graduate years as the number of years of college beyond 4 years if the person earned a bachelor’s degree. 5Along with the detailed educational data in the NLSY come instances of inconsistent reporting of educational attainment. There are cases in which a person has reported: earning a high school diploma, as opposed to earning a GED, without complet-ing the 12th grade; attendcomplet-ing college without earncomplet-ing a GED or completing the 12th grade; or earning a bachelor’s degree without having completed at least 3 years of college. I exclude from the sample respondents who fall into these categories. These three restrictions exclude 43, 10 and two individuals, respectively. I do, however, include individuals reporting hav-ing earned a GED and havhav-ing completed less than the 12th grade, and I include those who report completing the 12th grade, but not earning a GED or a high school diploma.

of the years of education completed, C is a vector of educational credentials, and R is a race dummy variable. The estimated relationships are not causal, for we would expect the skills reflected in the ability test scores to affect a person’s schooling decisions. Instead, the regressions show the association between pre-college ability and schooling.7While college likely affects

cog-nitive ability, the ability that can be inferred in this regression is only pre-college ability and is different from the skills learned in college.

Table 2 presents the results of regressions using the AFQT score and each individual score from the 10 tests in the ASVAB. To interpret the results, the coefficient estimate on a credential, say a bachelor’s degree, is the expected percentile difference in ability test scores between two individuals who have the same years of education completed and are observationally equivalent except that only one has a bachelor’s degree.

Completing each year of college is associated with higher pre-college AFQT scores. An employer can infer that someone who completes 2 years of college has 2.26 percentiles higher pre-college ability (in addition to the skills acquired during college) than someone who only completes 1 year of college. This estimate indicates that, among college attendees who do not graduate, those with higher pre-college ability proceed further in college. It would be difficult to reach similar conclusions for high school based on the estimates on years completed because the test was taken at different points in high school for the respondents.

The partial associations between the AFQT score and three of the primary educational credentials — a high school diploma, college attendance, and a bachelor’s degree — are statistically significant at the 1% signifi-cance level. A male with a high school diploma and no college is estimated to have an AFQT score that is 8.64 percentiles higher than an observationally equivalent per-son who completed 4 years of high school without com-pleting the requirements for a diploma. The difference in AFQT scores between a high school graduate who attends college for less than 1 year and a high school graduate who does not attend college is estimated to be 10.65 percentiles. This estimate indicates that merely attending college signals to employers greater pre-col-lege abilities than what is signaled by only graduating from high school. An associate’s degree does not appear to be a market signal of higher ability, as measured by the AFQT score. A possible explanation for this result

7It has been suggested that I regress the credentials on ability. However, I find Eq. (1) to be the most efficient means to determine the partial associations because it holds the years of school completed constant and indicates the actual differ-ences in ability rather than how much one percentile of ability increases the propensity to acquire a credential.

is that a year completed at a 2-year college may be less of a signal of ability than a year completed at a 4-year college. Since one cannot distinguish between a 2-year and a 4-year college education in the NLSY, the associ-ate’s degree may be picking up the lower ability associa-ted with a 2-year college education. The average differ-ence in pre-college AFQT scores between someone who earns a bachelor’s degree and a college dropout, holding constant the number of years of college completed, is estimated to be 9.07. Finally, an advanced degree is asso-ciated with 9.32 percentiles higher AFQT scores. The estimate is significant at the 10% level.

As for the 10 individual test scores of the ASVAB, college attendance appears to be the greatest signal of ability, while an associate’s degree appears not to signal higher ability at all. A high school diploma signals higher abilities associated with paragraph comprehension and math knowledge scores more than for any of the other scores. College attendance has a statistically sig-nificant coefficient estimate for each test score, and it signals word knowledge and math knowledge more than other skills. An associate’s degree does not signal sig-nificantly higher ability for any skill. A bachelor’s degree signals abilities associated with the three math tests more than any other abilities, and an advanced degree is only a signal of higher verbal abilities.

5. Do employers value educational credentials because they signal pre-college ability?

As just shown, certain credentials are strong signals of the skills reflected in the ability test scores. This does not, however, imply that employers value credentials because they signal these abilities. Employers may learn about workers’ abilities by other means such as school quality, so that the credential itself offers no new infor-mation. To determine whether employers value creden-tials for signaling pre-college cognitive abilities, I esti-mate a sorting model of wage determination. It is assumed that there is a sorting equilibrium in the labor market, indicating that the employers’ prior beliefs about what abilities credentials signal are supported by the edu-cational responses of new cohorts. For the sorting model, two equations are estimated:

ln(w)5a01Xa11Sa21Ca31u, (2)

ln(w)5b01Xb11Sb21Cb31Ab41v (3)

where ln(w) is the natural logarithm of a person’s hourly wage rate, X is a vector of characteristics affecting the wage rate and productivity, S and C are the same as in Eq. (1), A is a vector of ability test scores, and u and v are error terms capturing the effects of any components that are unobservable to the researcher. It is assumed that

J.

Arkes

/Economics

of

Education

Review

18

(1999)

133–141

Table 2

Regressions of each test score from the armed services vocational aptitude battery on educational attainment. Dependent variable5ASVAB test scores. Number of observations 51064

ASVAB test score

AFQT General Arithmetic Word Paragraph Numerical Coding speed Auto & shop Mathematics Mechanical Electronics science reasoning knowledge comprehension operations info knowledge comprehension info

High school 4.86*** 5.18*** 3.98*** 4.66*** 2.85** 4.52*** 5.71*** 4.18*** 0.95 2.48* 4.66*** years completed (1.18) (1.29) (1.28) (1.27) (1.32) (1.37) (1.43) (1.40) (1.26) (1.36) (1.38) College years 2.26** 2.37** 2.18** 2.74*** 2.77*** 1.07 1.89* 20.91 2.58*** 0.55 2.31** completed (0.93) (1.02) (1.01) (1.00) (1.04) (1.08) (1.13) (1.10) (1.00) (1.08) (1.09) Graduate years 2.22 5.07*** 4.10** 0.74 0.81 1.32 0.83 5.83*** 2.14 5.33*** 2.50 completed (1.69) (1.85) (1.84) (1.82) (1.89) (1.97) (2.05) (2.01) (1.81) (1.96) (1.99) High school 8.64*** 3.63 9.37*** 3.88 11.46*** 7.93** 0.32 7.43** 11.12*** 8.95** 3.59 diploma (3.15) (3.44) (3.44) (3.39) (3.52) (3.66) (3.82) (3.74) (3.37) (3.65) (3.70) College 10.65*** 8.46*** 7.43*** 11.48*** 9.29*** 8.70*** 8.16*** 4.59* 11.11*** 7.67*** 8.14*** attendance (1.98) (2.17) (2.16) (2.14) (2.22) (2.30) (2.40) (2.35) (2.12) (2.30) (2.33) Associate’s 0.22 1.08 21.71 21.17 22.09 4.03 3.43 0.50 2.79 2.86 22.63 degree (3.10) (3.39) (3.38) (3.34) (3.47) (3.61) (3.76) (3.68) (3.32) (3.59) (3.64) Bachelor’s 9.07*** 3.63 8.70** 4.13 5.72 11.31*** 8.53** 3.02 11.10*** 6.09 0.54 degree (3.38) (3.70) (3.69) (3.64) (3.78) (3.93) (4.10) (4.01) (3.62) (3.91) (3.97) Advanced degree 9.32* 4.46 0.73 12.25** 12.33** 6.60 4.06 28.23 9.04 23.44 4.76

(5.15) (5.52) (5.64) (5.55) (5.77) (5.99) (6.25) (6.11) (5.52) (5.97) (6.05)

White 21.98*** 23.33*** 20.68*** 21.46*** 17.69*** 15.45*** 14.91*** 28.85*** 14.37*** 23.88*** 22.71***

(1.33) (1.45) (1.45) (1.43) (1.49) (1.54) (1.61) (1.58) (1.42) (1.54) (1.56)

R-squared 0.520 0.426 0.430 0.440 0.399 0.351 0.294 0.325 0.445 0.355 0.337

Note: standard errors are in parentheses.

* Denotes significance at the 10% significance level. ** Denotes significance at the 5% significance level. *** Denotes significance at the 1% significance level.

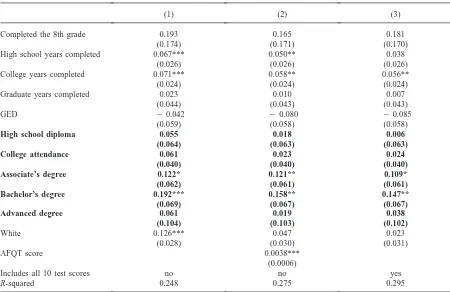

Table 3

The effect of the ability test scores on estimated wage premiums for educational credentials. Dependent variable5natural logarithm of average hourly earnings

(1993). Number of observations51064

(1) (2) (3)

Completed the 8th grade 0.193 0.165 0.181

(0.174) (0.171) (0.170)

High school years completed 0.067*** 0.050** 0.038

(0.026) (0.026) (0.026)

College years completed 0.071*** 0.058** 0.056**

(0.024) (0.024) (0.024)

Graduate years completed 0.023 0.010 0.007

(0.044) (0.043) (0.043)

GED 20.042 20.080 20.085

(0.059) (0.058) (0.058)

High school diploma 0.055 0.018 0.006

(0.064) (0.063) (0.063)

College attendance 0.061 0.023 0.024

(0.040) (0.040) (0.040)

Associate’s degree 0.122* 0.121** 0.109*

(0.062) (0.061) (0.061)

Bachelor’s degree 0.192*** 0.158** 0.147**

(0.069) (0.067) (0.067)

Advanced degree 0.061 0.019 0.038

(0.104) (0.103) (0.102)

White 0.126*** 0.047 0.023

(0.028) (0.030) (0.031)

AFQT score 0.0038***

(0.0006)

Includes all 10 test scores no no yes

R-squared 0.248 0.275 0.295

Note: standard errors are in parentheses.

* Denotes significance at the 10% significance level. ** Denotes significance at the 5% significance level. *** Denotes significance at the 1% significance level.

Other variables included in the wage equations but not reported are experience

(age minus years of education minus six), experience-squared and dummy variables for SMSA residence and region of residence.

0. The model further assumes that wages are proportional to (expected) productivity, that the propensity to acquire credentials is a linear function of ability, and that employers cannot observe A among labor force entrants. To identify whether and to what extent employers value credentials for signaling the skills reflected in the ability test scores, I compare the estimates ofa3andb3.

If employers value educational credentials for signaling these skills, then we should observe estimates ofb3that

are less than estimates of a3, because the portions of

the wage premiums attributable to signaling A are now captured byb4. If employers value credentials solely for

signaling the abilities reflected in A and ifa3is precisely

measured, then the estimates ofb3should be zero.

The difference in the estimates between a3 and b3

may, however, exaggerate the extent to which employers value credentials for signaling the abilities reflected in

A. If employers learn about workers’ abilities by using

other indicators that are unobservable to the researcher, say course grades, and if grades are correlated with the credentials — for example, those who perform well in the classroom may be more likely to graduate — then the coefficient estimates on the credentials may be reflecting wage premiums for high grades. The estimate for a3

would then be biased upwards. If ability measures are also correlated with the grades, thenb4in Eq. (3) may

capture some of the effects of grades, making the upward bias onb3less than that ona3. Consequently, including

Table 3 presents the coefficient estimates from the estimation of Eqs. (2) and (3). To interpret the coefficient estimate on a bachelor’s degree in column (1), for example, a person who has a bachelor’s degree earns on average 21.2% higher wages than an observationally equivalent person who does not have a bachelor’s degree but has the same number of years of education com-pleted.8 The coefficient estimate is statistically

signifi-cant at the 1% level. The estimate on an associate’s degree (0.122) is also statistically significant (p,0.10), despite the finding that an associate’s degree does not signal higher ability scores. This result indicates that an associate’s degree is rewarded for signaling abilities not reflected in the pre-college AFQT score or even for skills acquired while earning the associate’s degree.

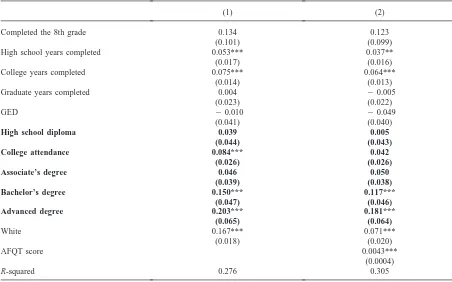

While the estimate on attending college is insignifi-cant, the estimate is statistically significant (0.084) at the 1% level when people of all ages from the NLSY are included, the results of which are presented in Table 4. While the estimate on an advanced degree is not signifi-cant for the restricted age group (in Table 3), it is large and statistically significant for the sample of all ages (in Table 4).

The differences in the estimates on the credentials between the cases of controlling and not controlling for the ability scores are indications of how much more a credentialled person is valued because of higher pre-sumed ability. Comparing columns (1) and (2) of Table 3, the inclusion of the AFQT score reduces the coef-ficient estimate on a bachelor’s degree by 0.034.9 The

difference is not statistically significant, but it suggests that, holding years of schooling constant, 3.4 percentage points of perceived productivity differences between workers with and without a bachelor’s degree are attribu-table to differences in presumed ability reflected in pre-college AFQT scores. While there are similar decreases in the estimates on a high school diploma, college attend-ance and an advattend-anced degree when ability is included, there is no evidence, given this sample, that there are productivity differences between those with and without these credentials. The finding that the estimate on an associate’s degree does not decrease while the estimates on the other credentials do decrease with the inclusion of ability is consistent with the fact that a high school diploma, college attendance and a bachelor’s degree sig-nal higher pre-college abilities, whereas an associate’s degree does not.

Column (3) of Table 3 presents the results for an

equ-8I derive this wage premium from the formula e21, where e is the coefficient estimate.

9Results for which a person can have both an associate’s and a bachelor’s degree are available upon request. When I include the AFQT score, the coefficient estimates change by amounts that are similar to those in Table 2.

ation that includes all 10 ASVAB scores. The purpose of this comparison is to determine if employers value credentials for signaling abilities that are reflected in the 10 individual scores that are not reflected in the AFQT score. Including all 10 of the ASVAB test scores gener-ally has little additional effect on the coefficient esti-mates on the credentials. The coefficient estiesti-mates on the credentials are reduced by at most 0.012 when I use all 10 test scores. Thus, employers are hardly rewarding cre-dentials for signaling the abilities that are reflected in the ASVAB test scores but not in the AFQT score alone.

6. Conclusions

The premise of this paper is that employers reward and value credentials because the acquisition of creden-tials signals certain traits that employers find worthwhile. There are, however, a few alternative explanations to the positive coefficient estimates on degrees being rewards for acquiring the degrees that must be considered. While no evidence is found by Frazis (1993) to support the Chi-swick (1973) hypothesis of wage premiums for degrees, his hypothesis is not disproved. It is plausible that people who experience greater benefits from each year of edu-cation are more likely to graduate, so that employers may reward a degree because it signals that the person learned more from schooling than others without a degree and not necessarily because it signals pre-college abilities. Second, the wage premiums for degrees could reflect a return to the quality of school. That is, people may be more likely to graduate at higher quality colleges, at which the instruction may be better.

Given the sorting model that I estimate, the results suggest that employers do value and reward a bachelor’s degree in part because it signals the abilities reflected in the pre-college ASVAB scores. For an associate’s degree and a bachelor’s degree, the coefficient estimates remain statistically significant with the inclusion of the ability scores. This indicates that employers may value associ-ate’s and bachelor’s degrees because the acquisition of these credentials marks unobservable attributes such as motivation, character and perseverance – attributes that seem to be associated, by employers, with greater per-formance and productivity. In conclusion, I find evidence indicating that a national test measuring cognitive abili-ties could convey part of, but certainly not all of, the information provided by workers acquiring credentials to signal their abilities.

Acknowledgements

Table 4

The effect of the AFQT score on estimated wage premiums for educational credentials including individuals of all ages — NLSY. Dependent variable5natural logarithm of the average hourly earnings

(1993). Number of observations52798

(1) (2)

Completed the 8th grade 0.134 0.123

(0.101) (0.099)

High school years completed 0.053*** 0.037**

(0.017) (0.016)

College years completed 0.075*** 0.064***

(0.014) (0.013)

Graduate years completed 0.004 20.005

(0.023) (0.022)

GED 20.010 20.049

(0.041) (0.040)

High school diploma 0.039 0.005

(0.044) (0.043)

College attendance 0.084*** 0.042

(0.026) (0.026)

Associate’s degree 0.046 0.050

(0.039) (0.038)

Bachelor’s degree 0.150*** 0.117***

(0.047) (0.046)

Advanced degree 0.203*** 0.181***

(0.065) (0.064)

White 0.167*** 0.071***

(0.018) (0.020)

AFQT score 0.0043***

(0.0004)

R-squared 0.276 0.305

Note: standard errors are in parentheses.

* Denotes significance at the 10% significance level. ** Denotes significance at the 5% significance level. *** Denotes significance at the 1% significance level.

Other variables included in the wage equations but not reported are experience

(age minus years of education minus six), experience-squared and dummy variables for SMSA residence and region of residence.

References

Belman, D., Heywood, J., 1991. Sheepskin effects in the returns to education: an examination of women and minorities. The Review of Economics and Statistics 73 (4), 720–724. Bishop, J., 1992. The impact of academic competencies on

wages, unemployment, and job performance. Carnegie– Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 37, 127–194. Chiswick, B. (1973) Schooling, screening, and income. In Does College Matter? (Edited by Lewis Solomon and Paul Taubman), pp. 151–158. New York: Academic Press. Frazis, H., 1993. Selection bias and the degree effect. The

Jour-nal of Human Resources 28 (3), 538–554.

Grubb, W.N., 1993. The varied economic returns to postsecond-ary education: new evidence from the class of 1972. The Journal of Human Resources 37 (2), 365–382.

Heywood, J., 1994. How widespread are sheepskin returns to

education in the U.S.? Economics of Education Review 13 (3), 227–234.

Hungerford, T., Solon, G., 1987. Sheepskin effects in the returns to education. The Review of Economics and Stat-istics 69 (1), 175–178.

Kane, T., Rouse, C., 1995. Labor market returns to two- and four-year college. American Economic Review 85 (3), 600–614.

Neal, D. and Johnson W. (1994) The role of pre-market factors in black–white wage differences. Working paper presented at Univ. of Wisconsin.

Spence, M. (1974) Market Signaling: Informational Transfer in Hiring and Related Screening Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Weiss, A., 1995. Human capital vs signaling explanations of wages. Journal of Economic Perspectives 9 (4), 134–155. Widgor, A. and Green, B. (editors) (1991) Performance