Ming T. Tsuang, William S. Stone, and Stephen V. Faraone

There is a growing emphasis on attempts to identify the early signs and symptoms of schizophrenia, largely be-cause early detection and treatment of psychosis (i.e., secondary prevention) are associated with relatively fa-vorable clinical outcomes. This raises the issue of whether prevention of psychosis itself is possible. The achievement of this goal will require the identification of a premorbid state that could serve as the foundation for treatment strategies aimed ultimately at the prevention of schizo-phrenia. Fortunately, evidence for such a state is emerg-ing, in part because schizophrenia may result from a neurodevelopmental disorder that is associated with a variety of clinical, neurobiological, and neuropsychologic features occurring well before the onset of psychosis. These features may serve as both indicators of risk for subsequent deterioration and the foundation of treatment efforts. We reformulated Meehl’s term schizotaxia to describe this liability and discuss here how its study could form the basis for future strategies of prevention. We also include a description of our initial attempts to devise treatment protocols for schizotaxia. It is concluded that schizotaxia is a feasible concept on which to base preven-tion efforts, and that treatment of adult schizotaxia may be among the next steps in the process. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:349 –356 © 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry

Key Words: Schizotaxia, genetics, negative symptoms, neuropsychology, risperidone

Introduction

D

uring the past decade, researchers have focused schizo-phrenia treatment studies on the early treatment of psychosis. Wyatt’s (1995) review of 21 controlled studies found that patients who had been treated with antipsychotic medicine during their first or second hospitalization had a better outcome than patients who had not been treated earlyin the course of illness. Others have suggested that early treatment, especially with newer agents, might preserve brain plasticity and reduce the clinical deterioration of chronic schizophrenia (Green and Schildkraut 1995; Lieberman 1996; McGlashan and Johannessen 1996). It is also possible that, rather than having a neuroprotective effect, early treat-ment mitigates the social consequences of schizophrenic psychopathology, which may result in better outcome by allowing for the easier reintegration of patients into their social networks. In fact, it may help prevent patients from losing these networks in the first place. These lines of reasoning have motivated the creation of early detection and intervention projects seeking to treat schizophrenic patients during their prodrome or first episode (Falloon et al 1996; Green and Schildkraut 1995; McGlashan 1996; McGlashan and Johannessen 1996; McGorry et al 1996; Olin and Mednick 1996; Vaglum 1996; Yung et al 1996).

The treatment of incipient psychosis is an outstanding secondary prevention strategy. But will it be enough? The compelling reasons for pursuing secondary prevention also provide compelling reasons for developing primary preven-tion protocols. There are, however, two reasons why the progress toward the primary prevention of schizophrenia remains in its infancy. First, we cannot implement a primary prevention protocol unless we can accurately define the population at risk for schizophrenia. Second, we must have a solid rationale for any proposed preventive treatment.

In this review, we outline an approach to these issues by focusing on “schizotaxia,” a term that Meehl (1962, 1989) introduced to describe the predisposition to schizophrenia and Faraone et al (in press) modified to fit with data collected since Meehl’s formulation. We begin with a brief discussion of the role of prevention in schizophrenia, and then outline the concept of schizotaxia. This leads to a consideration of how research into schizotaxia could facilitate the develop-ment of strategies for the primary prevention of schizophre-nia, followed by a description of our initial steps towards this goal, which include the establishment of research protocols for the treatment of schizotaxia in adults.

Early Identification and Treatment of

Schizophrenia

Although 100 years of research have not produced a cure for schizophrenia, we have made significant progress in its diagnosis and treatment, and in our understanding of its

From the Harvard Medical School Department of Psychiatry at Brockton/West Roxbury VA Medical Center and Massachusetts Mental Health Center (MTT, WSS, SVF), Psychiatry Service, Massachusetts General Hospital (MTT, SVF), Harvard Institute of Psychiatric Epidemiology and Genetics (MTT, WSS, SVF), and the Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health (MTT), Boston, Massachusetts.

Address reprint requests to Ming T. Tsuang, M.D., Ph.D., Stanley Cobb Professor of Psychiatry and Head, Harvard Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts Mental Health Center, 74 Fenwood Road, Boston MA 02115.

Received October 6, 1999; revised May 2, 2000; accepted May 9, 2000.

underlying neurobiology. A substantial portion of this credit goes to the development of antipsychotic drugs. Successive generations of these agents have had an enor-mous beneficial effect on the lives of patients and their families. Despite progress in treatment, there is clearly a long way to go before the symptoms of schizophrenia are fully “controlled” in most patients, in the sense that normal clinical and cognitive functions are restored (or attained). Thus, researchers have been testing secondary prevention strategies, which focus on the early detection and treat-ment of the disorder. In 1938 Cameron (cited in McGorry et al 1996) first described the need to treat schizophrenia early to prevent subsequent deterioration. Since then, evidence has accumulated to support the view that the longer treatment is delayed, the poorer is the subsequent prognosis (Green and Schildkraut 1995; Wyatt 1995; Wyatt et al 1996).

Several benefits of early treatment are likely, including the prevention of the social, interpersonal, cognitive, and affective disruptions that accompany and follow the initial psychotic episode. One potential consequence of second-ary prevention is simply the delay of onset. This may be especially valuable for early-onset cases, as these patients would then have more time to mature before having to cope with a serious and chronic illness. Moreover, un-treated schizophrenia may become more resistant to treat-ment, in part because psychosis itself may create wide-spread neurobiological abnormalities (Knoll et al 1998) that, at best, complicate current treatment strategies. If the early treatment of psychosis mitigates the course of schizophrenia, implementing early identification and treat-ment programs should be valuable because psychotic symptoms are present for an average of about 2 years before treatment is sought (e.g., Loebel et al 1992).

Research and theory about the early treatment of psy-chosis naturally lead to the question, can psypsy-chosis be avoided? Most researchers have approached the issue by focusing on prodromal symptoms as indicators of an impending psychotic disorder, but the issue is far from straightforward. McGorry et al (1995) showed, for exam-ple, that DSM-III-R prodromal symptoms for schizophre-nia occurred in 15–50% of high school students. This raises obvious questions about the validity of intervening on the basis of such symptoms. Are prodromal symptoms like social withdrawal, or subtle changes in thinking or affect, valid enough indicators of early schizophrenia to warrant intervention, possibly with antipsychotic medica-tions and their associated side effects? Do such nonspe-cific symptoms warrant the potential anxiety and stigma-tization (for both “patients” and their families) that might attend the classification of an individual as likely to develop schizophrenia, probably in the near future? Un-fortunately, these questions cannot yet be answered in the

affirmative. There is little clear evidence that prodromal symptoms are specific for schizophrenia or for other psychotic illness (Larsen and Opjordsmoen 1996). Given this state of affairs, the risks of primary prevention programs are magnified even further if high-risk status is assigned and interventions are proposed before clinical symptoms emerge.

Our current state of knowledge, then, appears to pre-clude the application of preventative treatments for people without clinical symptoms of psychosis, or at least the prodrome. If this is so, how might prevention strategies proceed?

Schizotaxia: Toward a Definition of

“Preschizophrenia”

The concept of schizotaxia was first introduced by Meehl to describe a “neural integrative defect” that was the neurobiological consequence of the schizophrenia’s ge-netic origins (Meehl 1962). In other words, schizotaxia was intended to describe the genetic vulnerability to schizophrenia. Meehl suggested that all individuals with schizotaxia would, through the normal processes of social learning, develop schizotypal personality structures. De-pending on the protection or liability afforded by environ-mental circumstances, a minority of these individuals would decompensate and develop schizophrenia. Over the next 25 years, Meehl revised the concept to allow for the possibility that some people with schizotaxia would de-velop neither schizophrenia nor schizotypal personality disorder (Meehl 1989). Although the term schizotaxia

achieved popularity in the research literature as a broad description of clinical or biological features thought to reflect the genetic liability for schizophrenia, it did not enter the clinical psychiatric nomenclature.

et al 1995). Particular areas of deficit frequently include attention/working memory, long-term verbal memory, and executive functions.

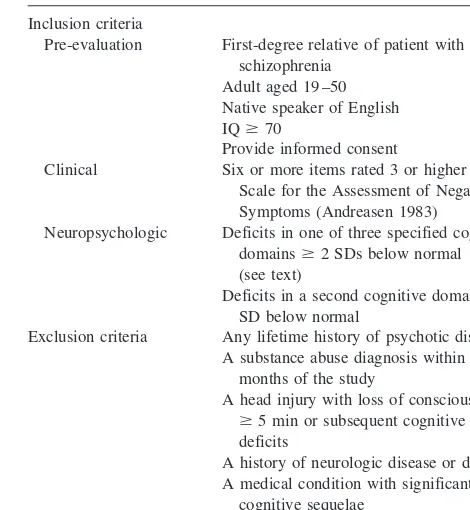

Recently we suggested modifications to the concept of schizotaxia that focused on negative symptoms and neu-ropsychologic deficits (Faraone et al, in press; also see Table 1 for a summary of our tentative research criteria for the assessment of schizotaxia). Our empirical analyses showed that the percentage of adult relatives who demon-strated these features among first-degree biological rela-tives of schizophrenic patients is substantial. Unlike schizotypal personality disorder, which occurs in less than 10% of the adult relatives of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (Battaglia and Torgersen 1996), and schizo-phrenia, which occurs in about 10% of first-degree rela-tives (Gottesman 1991), these basic symptoms of schizo-taxia occur in 20 –50% of adult relatives (Faraone et al 1995a, 1995b, in press). These findings indicate that the genetic liability to schizophrenia does not lead inevitably to either schizophrenia or schizotypal personality disorder. Our concept of schizotaxia has several advantages. One is its usefulness for genetic studies (Faraone et al 1999). If the proportion of first-degree relatives with schizotaxia is larger than the proportions of relatives with other related conditions (like schizotypal personality disorder or schizo-phrenia), then the classification of schizotaxia may allow for a more accurate differentiation of individuals who are genetically “affected” from those who are not (for a review of the technical aspects of this issue, see Faraone et al 1995a). Second, the utilization of neuropsychologic symptoms in our reformulation emphasizes “endopheno-typic” measures (Gottesman 1991) that are more proximal to their underlying genetic/biological etiologies than are the relatively end-state clinical symptoms that define schizophrenia and schizotypal personality disorder. Third, and most relevant for this discussion, schizotaxia extends the spectrum of liability to schizophrenia to a clinically meaningful but premorbid state. This makes it ideal for identifying preschizophrenic persons and for designing primary prevention strategies for schizophrenia.

Although our initial characterizations of schizotaxia are encouraging, it is an evolving concept rather than a strictly defined diagnostic condition. As noted above, the concept needs to be validated empirically, and criteria sets need to be established to differentiate it reliably from potentially comorbid conditions like schizotypal personality disorder. It is also likely that schizotaxia will come to incorporate biological measures of dysfunction caused by combina-tions of schizophrenia genes and adverse environmental events.

Our view of schizotaxia is consistent with neurodevel-opmental models of schizophrenia. Consistent with other neurodevelopmental hypotheses (Goldman-Rakic 1995;

Seidman 1990; Weinberger 1995a, 1995b), we hypothe-size that a combination of genes and environmental events leads to altered development of the brain, perhaps as early as the second trimester of life. This combination results in schizotaxia, which is a neurodevelopmental syndrome that is characterized by neuropsychologic and neurobiological dysfunctions, the latter of which may include reduced volumes in several brain areas, and/or altered patterns of brain activation in response to external challenges or stimuli (Seidman 1997).

Evidence in favor of neurodevelopmental hypotheses in schizophrenia is extensive (e.g., Beauregard and Bacheva-lier 1996; Faraone et al, in press; Tsuang and Faraone 1995; Tsuang et al 1991; Weinberger 1995a, 1995b; Woods 1998). Briefly, it includes 1) studies showing elevated rates of pregnancy and/or delivery problems, and exposure to viruses; 2) postmortem studies showing brain abnormalities indicative of second or third trimester prob-lems of development; 3) animal models demonstrating that neonatal hippocampal lesions produce effects that are not fully apparent until adulthood; 4) neuropsychologic defi-cits in nonpsychotic, first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia; 5) elevated rates of negative, but not positive, symptoms in schizophrenia families; and 6) evidence of brain volume loss before the onset of psy-chotic symptoms in some schizophrenic patients. Most of this evidence is consistent with the view that at least some significant aspects of the premorbid substrate of

schizo-Table 1. Preliminary Research Criteria for the Assessment of Schizotaxia

Inclusion criteria

Pre-evaluation First-degree relative of patient with schizophrenia

Adult aged 19 –50 Native speaker of English IQ$70

Provide informed consent

Clinical Six or more items rated 3 or higher on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (Andreasen 1983)

Neuropsychologic Deficits in one of three specified cognitive domains$2 SDs below normal (see text)

Deficits in a second cognitive domain$1 SD below normal

Exclusion criteria Any lifetime history of psychotic disorders A substance abuse diagnosis within 6

months of the study

A head injury with loss of consciousness

$5 min or subsequent cognitive deficits

A history of neurologic disease or damage A medical condition with significant

cognitive sequelae

phrenia are formed before the onset of the illness. Nega-tive symptoms and neuropsychologic deficits in family members, for example, are significant because they occur in schizophrenia, and in some family members who later develop schizophrenia or a related disorder. The extent to which factors like pregnancy and delivery complications increase the liability for schizophrenia remains to be established, as does their specificity, although a variety of studies have shown them to be elevated in schizophrenic patients (Zornberg et al 2000). Evidence for prenatal viruses is less clear, but remains suggestive (Tsuang and Faraone 1995).

Our view of schizotaxia fits in with another feature of the neurodevelopmental models noted above. For reasons that remain unknown, the syndrome sometimes results in psychosis (i.e., schizophrenia) and sometimes does not. Moreover, the notion of schizotaxia as a neurodevelop-mental disorder with genetic and environneurodevelop-mental etiologic components, and variable outcomes, also parallels diathe-sis/stress conceptualizations of the origins of schizophre-nia (Gottesman 1991). Each of these views emphasizes the importance of genetic/biological risk factors for schizo-phrenia. If, as suggested above, these factors constitute the premorbid substrate of the disorder, then it may be possible to intervene therapeutically before schizophrenia emerges. Because early treatment is associated with better outcomes, these views are thus consistent with the hypoth-esis that successful treatments of schizotaxia will modify or even prevent its subsequent progression to a more severe disorder, such as schizophrenia.

The Schizotaxia Treatment Protocol: A

Prelude to Prevention

One key to the prevention of schizophrenia will be the identification of abnormalities that reflect the etiologic processes that lead to the onset of psychosis. This means that, in addition to assessing clinical symptoms, there is a need for assessing areas of dysfunction that are closer than clinical symptoms to the etiologic process that ultimately causes schizophrenia. Indeed, a significant weakness of the reliance on prodromal symptoms, and one that is related to their lack of prognostic specificity, is that they often reflect relatively distal effects of etiologic processes. Fortunately, we are at a point where we are not limited to the use of clinical symptoms alone to identify the vulner-ability for schizophrenia.

Given the hypothesis that features of schizotaxia reflect the predisposition to schizophrenia, what steps must be taken to design a strategy aimed at preventing schizophre-nia? Clearly, the validity of schizotaxia as a predictor of subsequent schizophrenia must be firmly established. As Robins and Guze (1970) pointed out, it is crucial to

establish both the concurrent and predictive validities of putative syndromes. Does the classification of schizotaxia predict neuropsychologic, neuroimaging, or psychophysi-ologic findings that are consistent with what is known about the neurobiology of schizophrenia? As we have reviewed elsewhere, a growing body of literature suggests that the answer is yes (Faraone et al, in press). Abnormal-ities found among relatives of schizophrenic patients include eye-tracking dysfunction (Levy et al 1994), allu-sive thinking (Catts et al 1993), neurologic signs (Erlen-meyer-Kimling et al 1982), characteristic auditory-evoked potentials (Friedman and Squires-Wheeler 1994), neuro-imaging-assessed brain abnormalities (Seidman et al 1997), and neuropsychologic impairment (Kremen et al 1994).

More importantly, does schizotaxia predict the subse-quent emergence of psychotic symptoms or other forms of psychopathology? Studies of children at risk for schizo-phrenia show that schizotaxic features do predict subse-quent schizophrenia and related disorders (Auerbach et al 1993; Dworkin et al 1994; Erlenmeyer-Kimling 2000; Ingraham et al 1995; Olin and Mednick 1996; L. Erlen-meyer-Kimling, personal communication, 1997). But more work is needed to create measures of schizotaxia that will accurately classify children who do and do not go on to become schizophrenic. It should be noted that the issue of risk factors in schizotaxia also raises the issue of “protective” factors to mitigate them. Like risk factors, protective factors may be genetic/biological and/or envi-ronmental (Tsuang 2000). We use the term here to describe independent factors that reduce risk, rather than using it to describe the absence of factors that confer risk. This is an intriguing notion that has been difficult to pursue (deficits have been more amenable to detection), but that will hopefully “come of age” with advances in technology.

Although schizotaxic features cannot yet be used to select preschizophrenic children for primary prevention protocols, our current knowledge about schizotaxia sug-gests a method for evaluating medications that may someday be useful for the prevention of schizophrenia. This method, which we call the “schizotaxia treatment protocol,” is straightforward: select a sample of schizo-taxic first-degree relatives of schizophrenic patients and, using standard randomized clinical trial methodology, determine if a putative preventative treatment modifies the features of schizotaxia in an acute trial. Presumably, any medicine that mitigates the features of schizotaxia will be a reasonable candidate for a primary prevention trial when such trials are possible.

and pathophysiologic pathways with preschizophrenic people. If this assumption is true, then any medication that targets these pathways to mitigate schizotaxic features may also work to reduce the likelihood of the onset of psychosis. This assumption is reasonable because 1) first-degree relatives of schizophrenic patients are at high risk for carrying schizophrenia susceptibility genes (Gottes-man 1991) and 2) the features of schizotaxia observed among these relatives are similar to the features of schizotaxia seen in children who eventually become schizophrenic (Faraone et al, in press).

A major advantage of the schizotaxia treatment protocol is that it can avoid some of the ethical issues raised by primary prevention studies of schizophrenia. Prevention studies will label children and adolescents as potential future schizophrenic persons. This opens up the possibility of stigmatization and psychologic harm to the subject and their families. It is also possible that medications chosen for prevention trials may pose greater risks to children and adolescents than adults. That would preclude their use in the absence of a solid rationale for efficacy. But because schizotaxia can be defined in the adult relatives of schizo-phrenic patients, using an acute schizotaxia trial for putative preventative medicines will not require studies of children or adolescents.

We view the schizotaxia treatment protocol as a model system for testing hypotheses about primary prevention. It is a model because only some elements of the risk for schizophrenia are present. This is analogous to the use of animal models of disorders that attempt to define and manipulate specified components of the system. Such models are useful in that they facilitate focused analyses of the behavior of simpler systems. Moreover, models are often necessary because the ultimate goal of the research is not yet amenable to study for other reasons. In the case of prevention research for schizophrenia, the ethical and safety concerns about identifying and treating “high-risk” children still outweigh the benefits of proceeding with such studies. Eventually, however, as elements are incor-porated into the models, the comprehensiveness of the system, and its approximation to the condition of interest, increases. In this case, our model of the prevention of schizophrenia starts out as the treatment of clinically meaningful symptoms in schizotaxia, in adults.

If successful treatments are developed and tested, and the syndrome of schizotaxia is validated, then treatments at earlier ages may be considered. For example, if an acute schizotaxia treatment trial in adults is successful, one might consider an acute trial for adolescents. If an adoles-cent trial were to be successful, then we might consider a trial to prevent psychosis (assuming that the target, pre-schizophrenic population could be accurately defined).

One of the difficulties with implementing the

schizo-taxia treatment protocol is the lack of a consensual definition of schizotaxia. Although we can make many measurements of schizotaxic features (e.g., neuropsycho-logic symptoms, negative symptoms, social functioning), the field has yet to agree on how these measures should be combined to create a schizotaxic category.

Tsuang et al (1999) recently described a working definition of schizotaxia based on a set of specific criteria, for the purpose of developing a treatment protocol. Table 1 shows our initial research criteria for the diagnosis of schizotaxia.

The cognitive domains included vigilance/working memory, long-term verbal memory, and executive func-tions. Specific tests and measures on tests were used to meet the neuropsychologic criteria (Tsuang et al 1999). Our decision to require moderate deficits in different domains ensured that our initial treatment attempts would include only adults with demonstrable clinical and neuro-psychologic difficulties. This was important both to dem-onstrate the clinically meaningful nature of schizotaxia and to make the risk/benefit assessment of treatment more favorable. Although we wanted to start with a restrictive set of criteria, it is likely that modifications will be necessary in order to conduct large-scale studies. Some of the exclusion criteria in particular, like that involving substance abuse diagnoses, may need to be altered if requisite numbers of subjects are to be enrolled in research protocols. Nevertheless, the stringent nature of the criteria underscores the clinical meaningfulness of schizotaxia and the potential importance of developing treatment protocols to attenuate it, independent of its value as a strategy to prevent schizophrenia.

Our first application of the schizotaxia treatment protocol (Tsuang et al 1999) used risperidone, a novel antipsychotic medication. As we noted above, trials of these medications would appear reasonable on the basis of our assumption that individuals with schizotaxia share etiologic and psychopatho-logic elements with schizophrenia. Trials with the older, typical antipsychotics, however, were limited by reluctance to use these medications in nonpsychotic populations, mainly because of their side effects and subsequently high rates of noncompliance (Hymowitz et al 1986), but also because of their essential inability to alleviate negative symptoms (Marder and Meibach 1994) or neuropsychologic deficits (Cassens et al 1990).

1997). Notably, it also improved cognitive functions in schizophrenia, especially in attention or working memory (Green et al 1997; Rossi et al 1997; Stip 1996), but possibly in verbal long-term memory (Stip 1996) and executive functions (Rossi et al 1997) as well. This latter feature was especially important given that neuropsycho-logic impairment is a hallmark of schizotaxia.

Based on these issues, we began an open trial of risperidone with people who met our criteria for schizo-taxia (Tsuang et al 1999). After all entrance criteria were met, subjects received low doses (starting at 0.25 mg and reaching maximum doses of 2.0 mg) of risperidone for 6 weeks. During that period they were evaluated weekly for side effects and for clinical and neuropsychologic effects of treatment. After 6 weeks most clinical and neuropsy-chologic tests were repeated. We reported on the effects of treatment in our first four cases (Tsuang et al 1999) and have since completed two additional cases. Five out of six cases showed marked improvements in a demanding test of auditory attention (improvements were 1.5–2.0 SDs in magnitude, which placed subjects in the normal range of performance), and all subjects showed reduced negative symptoms after 6 weeks. In three cases, reductions in negative symptoms were marked (approximately 50% reductions in total Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms scores), whereas in two they were modest (25% reductions). One individual did not improve in either cognition or negative symptoms. Interestingly, this subject had lower overall cognitive abilities (an IQ of 75) than did the other cases (IQs ranged from 92 to 111). Her low test scores may thus represent the effect of two interrelated but distinct problems: schizotaxiaandlow cognitive abilities. In this view, the treatment may have been effective against symptoms of schizotaxia, but ineffective against the more general problem of limited intellectual abilities. Conse-quently, this subject did not improve with treatment.

Side effects, when they occurred, were mild to modest in severity. No one requested the discontinuation of treatment, but in some cases the doses were lowered to reduce discomfort. Side effects tended to differ between cases, but included symptoms such as dry mouth, sedation, and weight gain.

Future Directions

Our initial application of the schizotaxia treatment proto-col is encouraging, as five out of six cases showed reductions in negative symptoms and neuropsychologic deficits. We stress the preliminary nature of these findings, however, and do not yet recommend the use of risperidone or other medications to treat schizotaxia. Larger, con-trolled studies are needed to determine if the treatment implications of these pilot findings are correct.

Despite this caveat, our findings suggest the feasibil-ity of developing treatment strategies for adult schizo-taxia. It is clear that we are only starting this process. Perhaps the most important task for the near future, in addition to the need for more methodologically rigorous replications, is the validation of schizotaxia as a syn-drome. This process will likely include the eventual incorporation of additional clinical, neurobiological, neuropsychologic, and neurodevelopmental measures. At some point it will also include molecular biological data, as the genes that cause schizotaxia are located. As the validity of schizotaxia becomes established, the risk (for subsequent psychosis) provided by its component features will become measurable. That knowledge base will provide the foundation for strategies aimed at the prevention of schizophrenia, hopefully in the not too distant future.

Preparation of this chapter was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health Grants Nos. 1 R01MH4187901, 5 UO1 MH4631802, and 1R37MH4351801 (MTT); the Veterans Administration’s Medical Research, Health Services Research, and Development and Cooperative Studies Programs; and a National Alliance for Research on Schizophre-nia and Depression Distinguished Investigator Award (MTT).

References

Andreasen NC (1983):The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS).Iowa City: The University of Iowa. Auerbach J, Hans S, Marcus J (1993): Neurobehavioral

function-ing and social behavior of children at risk for schizophrenia.

Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci30:40 – 49.

Battaglia M, Torgersen S (1996): Schizotypal disorder: at the crossroads of genetics and nosology. Acta Psychiatr Scand

94:303–310.

Beauregard M, Bachevalier J (1996): Neonatal insult to the hippocampal region and schizophrenia: a review and a puta-tive animal model.Can J Psychiatry41:446 – 456.

Cassens G, Inglis AK, Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG (1990): Neuroleptics: Effects on neuropsychological function in chronic schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull 16:477– 499.

Catts SV, McConaghy N, Ward PB, Fox AM, Hadzi-Pavlovic D (1993): Allusive thinking in parents of schizophrenics. Meta-analysis.J Nerv Ment Dis181:298 –302.

Dworkin R, Lewis J, Cornblatt B, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L (1994): Social competence deficits in adolescents at risk for schizo-phrenia.J Nerv Ment Dis182:103–108.

Erlenmeyer-Kimling L (2000): Neurobehavioral deficits in off-spring of schizophrenic parents: Liability indicators and predictors of illness.Am J Med Genet97:65–71.

Schizophrenia as a Brain Disease.New York: Oxford Uni-versity Press, 61–98.

Falloon IRH, Kydd RR, Coverdale JH, Laidlaw TM (1996): Early detection and intervention for initial episodes of schizo-phrenia.Schizophr Bull22:271–282.

Faraone SV, Green AI, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT (in press): “Schizotaxia”: Clinical implications and new directions for research.Schizophr Bull.

Faraone SV, Kremen WS, Lyons MJ, Pepple JR, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT (1995a): Diagnostic accuracy and linkage anal-ysis: How useful are schizophrenia spectrum phenotypes?

Am J Psychiatry152:1286 –1290.

Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, Kremen WS, Pepple JR, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT (1995b): Neuropsychological functioning among the nonpsychotic relatives of schizophrenic pa-tients: A diagnostic efficiency analysis.J Abnorm Psychol

104:286 –304.

Faraone SV, Tsuang D, Tsuang MT (1999):Genetics of Mental Disorders: A Guide for Students, Clinicians, and Research-ers.New York: Guilford.

Friedman D, Squires-Wheeler E (1994): Event-related potentials (ERPs) as indicators of risk for schizophrenia.Schizophr Bull

20:63–74.

Goldman-Rakic PS (1995): More clues to “latent” schizophrenia point to developmental origins. Am J Psychiatry 152:1701– 1703.

Gottesman II (1991): Schizophrenia Genesis: The Origin of Madness.New York: Freeman.

Green AI, Schildkraut JJ (1995): Should clozapine be a first-line treatment for schizophrenia? The rationale for a double-blind clinical trial in first-episode patients.Harvard Rev Psychiatry

3:1–9.

Green MF, Marshall BDJ, Wirshing WC, Ames D, Marder SR, McGurk S, et al (1997): Does risperidone improve verbal working memory in treatment-resistant schizophrenia?Am J Psychiatry154:799 – 804.

Hymowitz P, Frances A, Jacobsberg LB, Sickles M, Hoyt R (1986): Neuroleptic treatment of schizotypal personality dis-orders.Compr Psychiatry27:267–271.

Ingraham LK, Kugelmass S, Frenkel E, Nathan M, Mirsky AF (1995): Twenty-five year follow-up of the Israeli High-Risk study: Current and lifetime psychopathology.Schizophr Bull

21:183–192.

Knoll JL, Garver DL, Ramberg JE, Kingsbury SJ, Croissant D, McDermott B (1998): Heterogeneity of the psychoses: Is there a neurodegenerative psychosis?Schizophr Bull24:365–379. Kremen WS, Seidman LJ, Pepple JR, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT,

Faraone SV (1994): Neuropsychological risk indicators for schizophrenia: A review of family studies. Schizophr Bull

20:103–119.

Larsen TK, Opjordsmoen S (1996): Early identification and treatment of schizophrenia: Conceptual and ethical consider-ations.Psychiatry59:371–380.

Levy DL, Holzman PS, Matthysse S, Mendell NR (1994): Eye tracking and schizophrenia: A selective review. Schizophr Bull20:47– 62.

Lieberman JA (1996): Atypical antipsychotic drugs as a first-line treatment of schizophrenia: A rationale and hypothesis.J Clin Psychiatry57(suppl 11):68 –71.

Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JMJ, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, Szymanski DO (1992): Duration of psychosis and out-come in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 149: 1183–1188.

Marder S, Meibach R (1994): Risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia.Am J Psychiatry151:825– 835.

McGlashan TH (1996): Early detection and intervention in schizophrenia: Research.Schizophr Bull22:327–345. McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO (1996): Early detection and

intervention with schizophrenia: Rationale. Schizophr Bull

22:201–222.

McGorry PD, Edwards J, Mihalopoulos C, Harrigan SM, Jackson HJ (1996): EPPIC: An evolving system of early detection and optimal management. Schizophr Bull 22: 305–326.

McGorry PD, McFarlane C, Patton GC (1995): The preva-lence of prodromal features of schizophrenia in adoles-cence: A preliminary survey. Acta Psychiatr Scand 92: 241–249.

Meehl PE (1962): Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. Am Psychol17:827– 838.

Meehl PE (1989): Schizotaxia revisited. Arch Gen Psychiatry

46:935–944.

Olin SC, Mednick SA (1996): Risk factors of psychosis: Identi-fying vulnerable populations premorbidly. Schizophr Bull

22:223–240.

Park S, Holzman PS, Goldman-Rakic PS (1995): Spatial working memory deficits in the relatives of schizophrenic patients.

Arch Gen Psychiatry52:821– 828.

Robins E, Guze SB (1970): Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: Its application to schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry126:983–987.

Rossi A, Mancini F, Stratta P, Mattei P, Gismondi R, Pozzi F, Casacchia M (1997): Risperidone, negative symptoms and cognitive deficit in schizophrenia: An open study. Acta Psychiatr Scand95:40 – 43.

Seidman LJ (1990): The neuropsychology of schizophrenia: A neurodevelopmental and case study approach.J Neuropsychi-atry2:301–312.

Seidman LJ (1997): Clinical neuroscience and epidemiology in schizophrenia.Harvard Rev Psychiatry3:338 –342. Seidman LJ, Faraone SV, Goldstein JM, Goodman JM,

Kremen WS, Matsuda G, et al (1997): Reduced subcortical brain volumes in nonpsychotic siblings of schizophrenic patients: A pilot MRI Study.Am J Med Genet74:507–514. Stip E (1996): The effect of Risperidone on cognition in patients

with schizophrenia.Can J Psychiatry41:S35–S40.

Tamminga CA (1997): The promise of new drugs for schizo-phrenia treatment.Can J Psychiatry42:265–273.

Tsuang MT (2000): Genes, environment, and mental health wellness.Am J Psychiatry157:489 – 491.

Tsuang MT, Andreasen N, editors.Positive vs. Negative Schizophrenia.New York: Springer-Verlag, 265–291. Tsuang MT, Stone WS, Seidman LJ, et al (1999): Treatment of

nonpsychotic relatives of patients with schizophrenia: Four case studies.Biol Psychiatry45:1412–1418.

Vaglum P (1996): Earlier detection and intervention in schizo-phrenia: Unsolved questions.Schizophr Bull 22:347–352. Weinberger DR (1995a): Neurodevelopmental perspectives on schizophrenia. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ, editors. Psycho-pharmacology: The Fourth Generation of Progress. New York: Raven, 1171–1183.

Weinberger DR (1995b): Schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmen-tal disorder: A review of the concept. In: Hirsch SR, Wein-berger DR, editors.Schizophrenia.London: Blackwell Sci-ence, 293–323.

Woods BT (1998): Is schizophrenia a progressive neurodevelop-mental disorder? Toward a unitary pathogenetic mechanism.

Am J Psychiatry155:1661–1670.

Wyatt RJ (1995): Early intervention for schizophrenia: Can the course of the illness be altered?Biol Psychiatry38:1–3. Wyatt RJ, Apud JA, Potkin S (1996): New directions in the

prevention and treatment of schizophrenia: A biological perspective.Psychiatry59:357–370.

Yung AR, McGorry PD, McFaarlane CA, Jackson HJ, Patton GC, Rakkar A (1996): Monitoring and care of young people at incipient risk of psychosis.Schizophr Bull22:283–304. Zornberg GL, Buka SL, Tsuang MT (2000): Hypoxic