Paul Allen Salisbury

ABSTRACT

All organizations need to acquire new customers to maintain and grow revenue as well as to replace customers lost through attrition. Cost-effective marketing requires a targeting strategy to focus on appropriate candidates for acquisition. Organizations that are marketing green products and services, or plan to do so, need to know who they should target for acquisition. This paper examines this issue for two similar green issues on who will pay more to protect the environment? Everyone is never a prospect for a given product or service.

Keywords: Customer acquisition, target marketing, marketing sustainability, CHAID, data mining

INTRODUCTION

What do we mean when we say sustainability or green? Sustainability (green) is a broad concept (Manget et al. 2009) that covers both personal issues (e.g., buying organic food, using compact fluorescent light bulbs (cfls), riding mass transit, etc.), as well as broader

social concerns for the environment (e.g., supporting research for alternative fuels and energy sources, balancing economic and environmental priorities, paying higher federal taxes for gasoline, etc.). One comprehensive marketing perspective (Belz & Peattie 2009) emphasizes the satisfaction of consumer and business needs within the limits of our global ecosystem—keep our planet healthy, as well as our global/regional/local economy, while we satisfy our customers. However, in a democracy we may differ on what will keep the planet healthy—short term or long term, or even what is green (The Economist 2010). People may have different priorities on green social and personal issues, even when we agree on the general importance of green strategies and tactics.

In this paper a decision-tree model (Magidson 2005) is used to develop two U.S. consumer segmentations regarding personal willingness to pay higher prices to protect the environment. The emphasis is on actionable implications to help social marketers target segments to develop support for environmental concerns. One objective is to use the learning about the segments that support or oppose paying higher prices for sustainability in order to target them for customer acquisition campaigns.

Client Acquisition. One major issue for most organizations and their marketing managers is the acquisition of new clients, both for growth and to compensate for attrition (lost clients). Implicit in a typical segmentation analysis is the objective of improving targeted client acquisition and retention (Kotler & Armstrong 2004). Marketing managers need to be cost-effective in acquisition efforts and avoid outreach to the wrong segments. For example, focus on lookalikes of best customers, or best customers at the time of acquisition if there is a growth or client development period for becoming a best customer. Similarly, it is imperative to focus retention marketing efforts on the right (profitable) segments.

Dolnicar and Lazarevski (2008) found a disconnect for marketing managers in translating methodologically sophisticated academic segmentation research into actionable information. The industry managers view the academic work as a ‘black box’—difficult to interpret and apply for day-to-day marketing campaigns. One objective here is to translate the results of decision tree model into usable guidelines for industry, NGO, etc. marketers to test or use to develop support for environmental issues. For example, industry marketers will examine how their best customers perceive the benefits and values of their respective green campaigns. Then they will look for any overlap with the segments reviewed in this paper (Estrin 2010).

We need to understand more about green consumer segments. About 61% of U.S. consumers believe that green goods do not perform as well as conventional products (Bonini & Oppenheim 2008). Yet between 2005 and 2007 cfls went from under five percent of the U.S. light bulb market to about 20%. Who will pay more to protect the environment? Are we being too simplistic? Do consumers multi-task objectives in dealing with environmental issues?

In this paper we examine public opinion segmentations in the U.S. for two disparate sustainability issues with one common element—paying more to protect the environment:

Government Policy—Pay higher prices for gasoline through higher taxes

Government Policy—Pay more to support the environment.

THEORY

Yes, we need to understand more about green consumer segments, as well as consumers who do not support environmental social action. We need theory to guide us in the right directions.

In this paper we are trying to understand the meaning of environmental support as a type of social action in terms of who supports it (or is opposed to it). In future analyses we will look for other data sets that we can use to explore the why influences on support for both social and personal green issues, (e.g., family, community, and lifestyle) plus how they support a green issue, (e.g., pay extra, buy organic). Why should formal education, ideology and age play such a key role in support for paying extra to support environmental issues? More data needs to be collected to examine lifestyle impacts on support for environmental issues to help understand the who, how, when, where and why of tangible support.

Belz and Peattie remind us that while traditional marketing theory focuses on consumers as individuals, we are also susceptible to other influences:

Groups, (e.g., family, household, ethnic affiliation, political party).

Community groups, (e.g., social networks, clubs), local services, (e.g., available mass transportation, mandatory/voluntary home recycling, ease/difficulty of home recycling)

Lifestyles (Belz & Peattie 2009, p. 87)

o Material Simplicity—consume less, consider environmental impact of goods

o Human Scale-practising ‘small is beautiful’ and simplifying a lifestyle

o Ecological Awareness—conserve resources, reduce waste, reuse/recycle more

o Personal Growth—develop personal abilities, less reliance on commercial

sources

We need to understand how we integrate our subjective meaning with external influences to form social action plans (Giddens 1973). Our ways of making sense of the world, doing the right thing and appearing to do so, all impact our behaviour whether or not we support environmental issues.

Marketing managers of green products and services regularly review their customer segmentations to refine target groups and positioning strategies (Belz & Peattie 2009; McDonnell & Barlett 2009; Kotler & Armstrong 2004). In effect, they are constantly updating their understanding of what influences, drives and satisfies their client action segments. Furthermore, marketing managers must continually test the impact of new information about sustainability in fostering behaviour on their client segments (Vermeir & Verbeke 2006). On the flip side of practicality, marketers know that demographics are more available and reliable than lifestyle variables when renting lists for prospecting (client acquisition campaigns). This often means using demographic combinations as surrogates for lifestyle variables.

In the end, the key issue is always behaviour regardless of any attitudinal position. How do we impact behaviour and whose behaviour can we influence? Who are the low hanging fruit? Who are the challenges? What segments are in the middle?

Over time, market researchers may be able to develop a segmentation taxonomy for sustainability marketing. Consumers who value one priority (e.g., carbon tax by polluters) need not value another sustainable issue or behaviour, (e.g., gasoline tax to fund mass transit). However, there may be sustainability issue clusters that future research will uncover. Each perspective seems to be a constraint based on consumer knowledge or the lack of it (Press & Arnould 2009; Sharp 2008), experience, indirect information or experience from other people, some combination of influences, etc. Any consistency across sustainability issues will rely on subjective consumer perceptions of social meaning and action, rather than any external perceptions of logic.

Data and Analysis

CHAID: A Brief Overview

CHAID is an acronym for Chi-squared Automatic Interaction Detector. It is often used for data mining. The analysis here uses a categorical, (e.g., binary), dependent variable. CHAID employs the chi-square test (for categorical independent variables) to find the next best split among the independent variables and displays the results in a tree or waterfall diagram. It is effective for exploratory market segmentation, but larger data sets are needed due to the splits. The splits segment and reduce the total sample, akin to an extensive, multivariate cross-tabular model. Variables may be combined or split depending upon what produces the lowest p-value (Magidson 2005; Breur 2008).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Issue I. People Should Be Willing to Pay Higher Prices to Protect the Environment— Socio-Demographics Rule

‘People should be willing to pay higher prices in order to protect the environment. Do you completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree, or completely disagree?’ (No opinion or no answer were categorized with oppose for this analysis because they do not favor this position). This question does not specify how we may be impacted by higher prices. It is a general perspective and does not address specific objectives, (e.g., pay more for clean air, etc.).

Those who do not favor higher prices to protect the environment are more likely to: be conservative, be age 25 to 34, and be a high school graduate with no additional education, (see univariate information below).

Table 1: Socio-demographicOverview: Willing to Pay Higher Prices to Protect the Environment

% Favor % Do Not Favor

Ideology

Conservative 26 43

Moderate 41 37

Liberal 27 12

Don’t know/refused 6 8

Age

18 to 24 14 12

25 to 34 14 20

35 to 44 18 18

45 to 54 20 19

55 to 64 16 15

65 plus 17 17

Education

Less than high school graduate 14 13

High school graduate 30 39

Some college/technical training 24 26

College graduate plus 32 22

CHAID Analysis

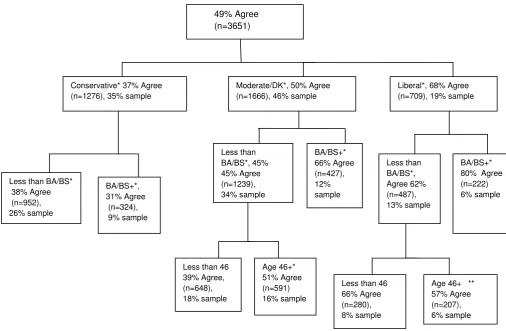

of education is vital too. We see that 80% of the liberals with a BA plus support paying higher prices, though they are just six percent of the population.

There is a key role for education in support for higher prices among moderates. Note that 66% of the moderates with a BA plus support paying higher prices, and they are 12% of the population. When we total the most educated groups across the ideological span between moderates and liberals, we see 18% of this sub-group contain significant percentages of people who support higher prices to protect the environment.

Next we see how age refines this group. For moderates, the people with a BA plus, or who are less educated and aged 45 or younger, are more apt to favour paying higher prices. Education and age clearly impact this position—especially education. Combining the educated moderates with all of the liberals provides 31% of the population with majorities to support higher prices to protect the environment. Lookalikes of these people should be fertile ground to look for potential converts to environmental support.

While demographics are key determinants in this study, demographics and socio-demographics have a mixed record on influencing green consumer behaviour, sometimes with contradictory results (McDonald & Oates 2006; Straughan & Roberts 1999). Gilg, Barr and Ford (2005) find socio-demographics (i.e.., age, gender, income, education and community involvement) impact green lifestyles along with psychological factors and social-environmental values (Olli, Grendstad & Wollebark 2001). Lin, Yen, Huang and Smith (2009) find that household income is what impacts the purchase of organic (vs. conventional) fruit. Zhang, Hussain, Deng and Letson (2007) saw a mix of demographics (having a full-time job, $75, 000 plus annual income, being an adult younger than age 56), and attitudes (willing to donate money to causes and interest in donating time to urban forestry) were predictors of awareness for urban tree programs. Similarly, Saphores, Nixon, Ogunseitan and Shapiro (2006) saw a mix of demographics (gender, education) and attitudes (convenience, environmental beliefs) were key factors in willingness to drop-off e-waste at recycling centers.

It is important to continue exploring this role for demographics in further research. This seeming inconsistency may be an indicator of the varying impact of demographics depending upon the specific sustainability issue. In addition, marketing managers must test the impacts of current information about availability and peer pressure in fostering behaviour on any

green issue (Vermeir & Verbeke 2006). In the end, the key issue is always behaviour regardless of any attitudinal position. Who should we target? Whose behaviour can we influence, and how? Who will be the loyal opposition?

Marketing managers who may be working with political groups or NGOs supporting this type of position can target educated people aged 45 or younger for campaigns. Social marketing can certainly help encourage conservation of resources (Peattie & Peattie 2009). Energy companies who may want to support any political opposition to such tax increases can see that voters with lower educational levels should be targeted—especially conservatives. In general, people with less than a BA are the basic target group of anti-pay more campaigns.

Table 2: Results of CHAID Analysis: People Should Be Willing to Pay Higher

Issue II. Higher Taxes and Prices for Gasoline: Demographics Rule

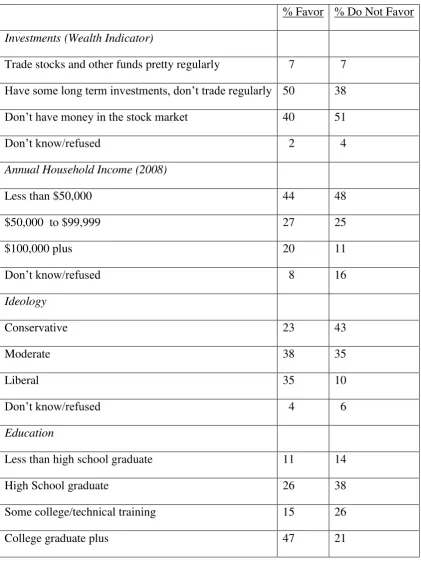

Those who favor increasing taxes on gasoline to increase conservation are more likely to: have some long term investments in the stock market, report an annual income above $100k, be liberal, and be more likely to have attended college or have a BA or additional education. At the univariate level they seem more educated, wealthier and more liberal.

Table 3: Socio-Demographic Overview: Support Gasoline Tax to Encourage Conservation

% Favor % Do Not Favor

Investments (Wealth Indicator)

Trade stocks and other funds pretty regularly 7 7

Have some long term investments, don’t trade regularly 50 38

Don’t have money in the stock market 40 51

Don’t know/refused 2 4

Annual Household Income (2008)

Less than $50,000 44 48

$50,000 to $99,999 27 25

$100,000 plus 20 11

Don’t know/refused 8 16

Ideology

Conservative 23 43

Moderate 38 35

Liberal 35 10

Don’t know/refused 4 6

Education

Less than high school graduate 11 14

High School graduate 26 38

Some college/technical training 15 26

CHAID Analysis

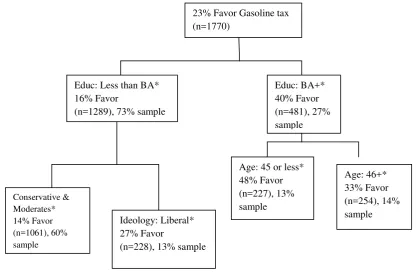

Among all the respondents queried, just 23% favoured increasing gasoline taxes to encourage conservation. This segment is clearly a target group of people willing to pay more (or have others pay more) for at least one issue. Note the role of education: 40% of those with a BA+ support the higher tax while only 16% of those with lower educational levels support the tax. People with a BA+ are 27% of the population, a substantial group for political campaigns.

Next, we see how age refines this group. Forty-eight percent of the people with a BA+ and

who are 45 or younger favour this tax increase. While only 33% of folks who have a BA +

and are age 46 or older favour this tax increase; however, they are significantly more supportive than the overall sample. Education and age clearly impact this position— especially education.

People with less than a BA show far less support for increasing gasoline taxes. Even when refined by political philosophy, the support of liberals with less than a BA only reaches 27%. While demographics are key determinants in this study, demographics and socio-demographics have a mixed record on influencing green consumer behaviour, sometimes with contradictory results (McDonald & Oates 2006l Straughan & Roberts 1999).

Gilg, Barr and Ford (2005) find socio-demographics (i.e.., age, gender, income, education and community involvement) impact green lifestyles along with psychological factors and social-environmental values (Olli, Grendstad & Wollebark 2001). Lin, Yen, Huang and Smith (2009) find that household income is what impacts the purchase of organic (vs. conventional) fruit. Zhang, Hussain, Deng and Letson (2007) saw a mix of demographics (having a full-time job, $75, 000 plus annual income, being an adult younger than age 56), and attitudes (willing to donate money to causes and interest in donating time to urban forestry) were predictors of awareness for urban tree programs. Similarly, Saphores, Nixon, Ogunseitan and Shapiro (2006) saw a mix of demographics (gender, education) and attitudes (convenience, environmental beliefs) were key factors in willingness to drop-off e-waste at recycling centres.

It is important to continue exploring this role, or the lack of it, in further research. This seeming inconsistency may be an indicator of the varying impact of demographics depending upon the sustainability issue.

In addition, marketing managers must test the impacts of information about availability and peer pressure in fostering behaviour on any green issue (Vermeir & Verbeke 2006). In the end, the key issue is always behaviour regardless of any attitudinal position. How do we impact behaviour and whose behaviour can we influence?

Marketing managers who may be working with political groups or NGOs supporting this type of position can target educated people age 45 or younger for campaigns. Social marketing can certainly help encourage conservation of resources (Belz & 2009). Energy companies who may want to support any political opposition to such tax increases, can see that voters with lower educational levels should be targeted—especially conservatives. In general, people with less than a BA should be the basic target group of anti-gasoline tax campaigns.

with few mass transit options, higher or lower local gasoline taxes, more usage of personal vehicles, etc.

Table 4: Results of CHAID Analysis: Support Gasoline Tax to Encourage Conservation

* Adjusted P-value = 0.000

CONCLUSIONS

Socio-demographics are key determinants of support for higher prices to protect the environment. There are differences on details:

Best customers. Liberal, educated people aged 46 plus are far more likely to support paying higher prices to protect the environment. Educated people under age 45 are more apt to support paying higher gasoline taxes. The common element is higher education—typically income is higher and we are better prepared to focus on environmental issues. Ideology, education and age are common influences of support in both issues—though the specifics may vary.

Additional support. Even among moderates, educated folks aged 46 plus are more likely to support paying higher prices for sustainability. While there is far less support for higher gasoline taxes among people with less than a college education, note that liberals are more supportive than conservatives and moderates by almost a two to one ratio. Again, education plus age and ideology help us find support for higher prices to protect the environment across two issues.

23% Favor Gasoline tax (n=1770)

Educ: Less than BA* 16% Favor

(n=1289), 73% sample

Educ: BA+* 40% Favor (n=481), 27% sample

Age: 46+* 33% Favor (n=254), 14% sample Age: 45 or less*

48% Favor (n=227), 13% sample

Conservative & Moderates* 14% Favor (n=1061), 60% sample

Ideology: Liberal* 27% Favor

However, it remains to be tested by industry, NGO and public sector marketers to see if this agreement translates into behaviour—actually paying higher prices for products and services to protect the environment. These educated consumer segments are people who are more formally sophisticated and apt to have socio-economic resources. The literature (see above) on the segments who support other green products or services also tend to be people with greater educational and financial resources—sometimes along with specific attitudes or lifestyles. This suggests that recommendations to educate the public on sustainability issues should be amended to include programs at institutions of higher education. In the long term, higher education seems to help people appreciate the value of green products and accumulate resources to pay for them.

While some of the segments that support green products include people with specific attitudes or lifestyle perspectives, this is apt to have limited value for hands-on communicators developing a communications strategy and media mix. They need to know more about media use by purpose, etc. The relative impact of socio-demographics, along with lifestyle characteristics and media use needs to be estimated to see if the socio-demographic influences are strong enough to warrant use as a surrogate for more detailed lifestyle information.

Clearly there is much to be learned about the many segments for sustainable products, services and policies. The long term goal of developing taxonomy of green segments should be productive.

REFERENCES

Belz, FM & Peattie, K 2009, Sustainability Marketing: A Global Perspective, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, West Sussex.

Bonini, SMJ, Oppenheim, JM 2008, ‘Helping ‘Green’ Products Grow’, McKinsey Quarterly, online publication

Breur, T 2008, ‘Decision Trees: Divide and Conquer’, paper, Xintconsulting, London, UK:

Conner, D, Colasanti, K, Ross, RB & Smalley, SB 2010, ‘Locally Grown Foods and Farmers Markets: Consumer Attitudes and Behavior’,Sustainability, 2, (3), 742-756.

Dolnicar, S & Lazarevski, K 2009, ‘Methodological Reasons for the Theory/Practice Divide in Market Segmentation’, Journal of Marketing Management, 25, (3-4), 357-373.

Giddens, A 1973, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim, and Max Weber, Cambridge University Press, London.

Gilg, A, Barr, S & Ford, N 2005, ‘Green Consumption or Sustainable Lifestyles? Identifying the Sustainable Consumer’, Futures, 37, 481-504.

Hopkins, MS 2010. ‘How SAP Made the Business Case for Sustainability: The MIT Sustainability Interview’, MIT Sloan Management Review, August 12, (e-publication).

Kassaye, WW 2001 ‘Green Dilemma ,Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 19, (6/7), 444-455.

Kotler, P & Armstrong, G 2004, Principles of Marketing, 10th edition, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

Liang, K, CP & Kamkatwong, S 2010, ‘Green Strategies and Green Marketing, International Journal of Strategic Marketing, February, online publication.

Lin, B-H, Yen, ST, Huang, CL & Smith, TA 2009, ‘U.S. Demand for Organic and Conventional Fresh Fruit: The Roles of Income and Price’, Sustainability, 1, (3), September, 464-478.

Luchs, M G, Naylor, RW, Irwin, J R & Ragahunathan, R 2010, ‘The Sustainability Liability: Potential Negative Effects of Ethicality on Product Preference’, Journal of Marketing, 74, (5), September, 18-36.

Lueneburger, C & Goleman, D 2010, ‘The Change Leadership Sustainability Demands’,

MITSloan Management Review, May 17, 1-6, (Reprint 51412)

Magidson, J 2005, SI-CHAID 4.0 User’s Guide, Statistical Innovations Inc., Belmont, MA.

Manget, J, Roche, C & Felix, M (2009), ‘Capturing the Green Advantage: What Green Consumers Want and How to Deliver it. For Real, Not Just for Show’, MITSloan Management Review (special report), (e-publication).

McDonald, S & Oates, CJ 2006, ‘Sustainability: Consumer Perceptions and Marketing Strategies’,Business Strategy and the Environment, 15, (3), May/June, 157-170.

McDonnell, JJ & Bartlett, JL 2009, Marketing to Change Public Opinion On Climate Change: A Case Study’, The International Journal of Climate Change: Impacts and Responses, 1, (3), 54-73.

Olli, E, Grendstad, G & Wollebark, D 2001, ‘Correlates of Environmental Behaviors: Bringing Back Social Context’, Environmental Behavior, 33, (2), 181-208.

Pekala, N 2009, ‘From Virtual Tote Bags to Earth-Friendly Deeds, Marketers Get Creative With 2009 Earth Day Campaigns’, AMA Marketing Matters Newsletter, April 20, online edition.

Peattie, K & Peattie, S 2009, ‘Social Marketing: A Pathway to Consumption Reduction?’

Journal of Business Research, 62, (2), 260-268.

Press, M & Arnould, EJ 2009, ‘Market System and Public Policy Challenges and Opportunities’,Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 28, (1), Spring, 102-113.

Princeton Survey Research Associates International. 2009, ‘Methodology 2009 Values Survey’. Pew Research Center for the People and the Press.

Saphores, J-D M, Nixon, H, Ogunseitan, OA & Shapiro, AA 2006, ‘Household Willingness to Recycle Electronic Waste: An Application to California’, Environment & Behavior, March, 38, 183-208.

Straughan, RD & Roberts, JA 1999, ‘Environmental Segmentation Alternatives: A Look at Green Consumer Behavior in the New Millennium’, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 16, (6), 558-575.

The Economist. 2010, Technology Quarterly, June 12, 1-28.

Tregear, A & Ness, M 2005, ‘Discriminant Analysis of Consumer Interest in Buying Locally Produced Foods’, Journal of Marketing Management, 21, (1-2), 19-35.

Vermeir, I & Verbeke, W 2006, ‘Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer Attitude – Behavioral Intention Gap’, Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 19, (2), 169-194.