The use of psychotropic

medication with adults with

learning disabilities: survey

findings and implications for

services

Melanie Chapman, Manchester Learning Disability Partnership, Mauldeth House, Mauldeth Road West, Manchester M21 7RL, UK;Paul Gledhill, Community Provision, Oakwood Resource Centre, Manchester Learning Disability Partnership, 177 Longley Lane, Northenden, Manchester M22 4HY, UK;

Phillip Jones, Supported Living Networks, Forrester House Resource Centre, 50 Blackwin Street, West Gorton, Manchester M12 5JY, UK;Mark Burton, Manchester Learning Disability Partnership, Mauldeth House, Mauldeth Road West, Manchester M21 7RL, UK andSaroj Soni, Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust, Oakwood Resource Centre, Manchester Learning Disability Partnership, 177 Longley Lane, Northenden, Manchester M22 4HY, UK

Summary

This paper describes the findings of a survey into prescribing of psychotropicmedication with adults with learning disabilities in a British city. A self-completion questionnaire was sent to staff in dispersed housing and community learning disability teams to gather information about the number of people prescribed psychoactive medication, the type of medication prescribed, General Practitioner and Consultant Psychiatrist visits.

The survey identified 55 people who were prescribed psychotropic medication. Of these, 89%were prescribed antipsychotic medication, whilst 47% were prescribed antidepressants. Forty-four per cent were prescribed more than one category of psychotropic medication, whilst 22%were prescribed more than one antipsychotic medication. Worryingly, a clear diagnosis was not provided in a large proportion of cases. The survey has informed a number of service developments, which are briefly described.

Keywords Community setting, medication reviews, mental health diagnosis, polyphar-macy, psychotropic medication, survey

Introduction

There has been much interest in the use of psychotropic medication with people with learning disabilities (Clarke

et al. 1990; Jenkins 2000). Mental health problems are reported to be more commonly experienced by people with learning disabilities (Osman 2000), and the use of psycho-tropic medication may be useful in the treatment of mental health problems. However, studies have shown that adults

medication in hospitals, community residential facilities, and family homes, there were no significant differences in the reported prevalence of behaviour disorders among the three populations. Typically, studies indicate prescribing rates of 35% in hospital settings, with lower rates in community residential settings, and the lowest rates in family settings (Clarkeet al.1990).

It is important that the prescribing of psychotropic medications balances the potential risks and benefits for individuals and is evidence-based. Psychotropic medication should not be used as a means of controlling behaviours or for sedation. Consideration needs to be given to the possible side-effects of such medication and the impact on an individual’s quality of life. Side effects can be debilitating (for example, restlessness, pacing, drowsiness, insomnia, tardive dyskinesia) and unpleasant (for example, dribbling, nausea, constipation) (British Medical Association 2001; Jenkins 2000). There is conflicting evidence as to whether some people with learning disabilities are at increased risk of developing short-term and long-term side-effects because of pre-existing neurological damage (Brylewski & Duggan 2004), whilst Aman (1984) raised concerns regarding the potential negative impact of antipsychotic medication on learning and the cognitive abilities of people with learning disabilities. However, communication barriers and lack of information may prevent people with learning disabilities reporting and others recognizing side-effects.

Polypharmacy (the administration of many drugs together) can exacerbate side-effects, lead to harmful inter-actions and neuroleptic malignant syndrome (Jenkins 2000). Of additional concern is evidence that the use of psycho-tropic medication may lead to increased risk of sudden cardiac death (Cohenet al.2001; Frassati et al.2004; Straus

et al.2004).

This survey arose from a desire to know more about local prescribing patterns. Whereas Clarke and colleagues were able to use a pre-existing register to explore prescribing patterns, there was a lack of robust systems locally to facilitate the collation of such information. A range of practitioners involved in supporting adults with learning disabilities may have prescribed medication, and there was a lack of information about the ‘medication history’ of people who had previously lived in an institutional setting, or who had recently moved into adult services. Locally, as nationally, there had been a shortage of Psychiatrists. The survey followed a 2-year period with only minimal locum cover, a common situation in learning disability services throughout the country. Thus there was concern over whether people had been receiving regular medication reviews.

As a consequence, in 1999/2000 the service undertook a survey to gain information about the use of psychotropic medication with people supported by the service. The survey was carried out as part of the service’s annual

programme of setting objectives to improve service effect-iveness, and was conducted by a group of community nurses with support from a researcher (MC) once the study was underway.

Aims

The survey aimed to collect information about:

• The type of medication taken by people supported by the

service and the reasons people are prescribed medication. • The extent of polypharmacy.

• How often medication is reviewed.

Method

Members of the group devised a questionnaire requesting the following information:

• Background details of the learning disabled person (age

and gender).

• Details of the person’s General Practitioner, the most

recent General Practitioner visit, any changes made to medication and reasons for these changes.

• Details of the person’s psychiatrist, diagnosis, the most

recent visit, any changes to medication and reasons for these changes.

• Details of current medication, reason for prescribing this

medication, length that medication had been prescribed, date of last review and next review.

The questionnaire was sent to managers of supported dispersed housing and community learning disability teams (CLDTs) to distribute to staff. Because of concerns about the amount of time it would take to complete questionnaires staff were asked to complete questionnaires for up to 10 people with learning disabilities supported by the service who were prescribed psychotropic medication and seen by a consultant psychiatrist. Information was obtained from records held at the person’s home or information held at the CLDTs. A reminder was sent to senior managers of the networks and CLDTs. Question-naires were not sent to independent providers, nor was information sought from GPs or from records held by Consultant Psychiatrists at this stage. A sample of 20 returned questionnaires was later compared with a psychiatrist’s records to evaluate the accuracy of the information included on the questionnaires.

Information from the questionnaires was entered on an SPSS database to allow statistical analysis.

Results

The sample

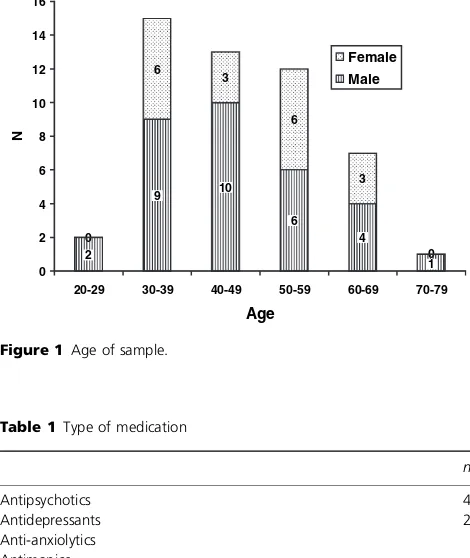

a high (85%) proportion of people living in supported accommodation. This represented 23% of the service’s dispersed housing network tenants at the time of the survey. Sixty-one per cent of the sample were male, whilst 39% were female. The youngest person was 27 years old and the oldest 72 (mean 47.04, SD 11.00). No data was provided for five people. Figure 1 demonstrates the age and gender of the people prescribed psychotropic medication.

Type of medication

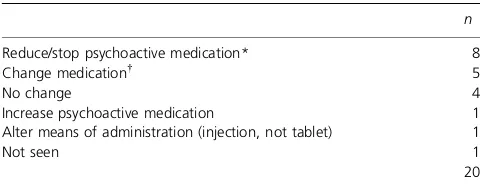

Medication was categorized by British National Formulary (BNF) type (British Medical Association, 2001). Table 1 summarizes the number of people prescribed each type of medication.

The most commonly prescribed psychotropic medications were risperidone (n¼14), sertraline (11), thioridazine (9),

chlorpromazine (8), haloperidol (6) and zuclopenthixol (6). All of these are types of antipsychotic medication, apart from sertraline which is an antidepressant. In addition, 13 people (23%) were prescribed anti-muscarinic medication prescribed to reduce parkinsonian side effects of anti-psychotic medication.

Diagnoses

There were a number of different mental health diagnoses amongst the group and also a significant number where no diagnosis was provided. Figure 2 gives the diagnosis (or nondiagnosis) for people identified by the survey.

A number of differing reasons were provided as to why medication had been prescribed. The reasons for prescribing antipsychotic and antidepressant medication are outlined in Table 2.

Length of time on medication and medication reviews

Thirty-six people prescribed antipsychotic medication had their medication reviewed in the previous year. One person’s medication had not been reviewed for 3 years, whilst it was not possible to identify when the previous review was for eight people. At least one person had been prescribed antipsychotic medication for over 10 years; it was not known or recorded when the medication was first prescribed for a further 12 people.

One person had been prescribed antidepressant medica-tion for over 5 years and informamedica-tion was not available about how long the medication had been prescribed for a further four people. For five people it was not known when the medication was last reviewed and another

0

20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 60-69 70-79

Age

Figure 1 Age of sample.

Table 1Type of medication

n

*Total is more than 55 as some people were prescribed more than one type of medication.

Table 2Reason for medication

Antipsychotics Antidepressants

n % n %

Mental health 9 18.4 5 19.2

Behaviour 18 36.7 6 23.1

Mental health & behaviour 7 14.3 1 3.8 Antipsychotic/antidepressant 8 16.3 13 50.1

Other 3 6.1 1 3.8

No reason given 4 8.2

Total 49 100.0 26.0 100.0

58.2

ophrenia Dementia Autism Epilepsy Mood disorder

PTSD

Diagnosis

%

person’s medication had not been reviewed for over a year. None of these six people had a date set to review their medication.

The extent of polypharmacy

Polypharmacy can be defined as the administration of many drugs together, or the administration of excessive medica-tion (Miller & Brackman 1987). For the purposes of this survey two measures of polypharmacy were used:

• When an individual is prescribed more than one type of

medication from the same BNF category (British Medical Association 2001) [note: PRN (prescribe when necessary) medication was also included].

• The number of different BNF categories of medication

prescribed to individuals (excluding anticonvulsants and antimuscarinics).

It is recognized that these are crude measures, and that more detailed examination would be needed to draw more reliable conclusions about whether the levels and combina-tions of medication were appropriate.

Of the 26 people prescribed antidepressant medication 21 people (81%) were also prescribed antipsychotic medica-tion, four (15%) an anti-anxiolytic and two (7%) antimanic medication.

Twenty-four people (44%) were prescribed medication from more than one category. Two people were pre-scribed medication from four of the five different categ-ories, two people from three categories and 20 people from two categories. Of those 49 people prescribed antipsychotic medication, 21 (43%) were also prescribed an antidepressant, five (10%) were prescribed anti-anxio-lytics and four (8%) antimanic medication. Twelve people were prescribed two types of antipsychotic medication; this represents 25% of people prescribed antipsychotic medication.

Discussion

This survey has provided information to improve local service provision, to enable comparisons with other dis-tricts, and to add to the existing evidence base on prescri-bing patterns. Future audits will permit monitoring of prescribing levels.

Prescribing levels and patterns

The figures are probably an under-representation of the actual number of people receiving psychoactive medica-tion as surveys rarely achieve 100% response rates and only people seen by a consultant psychiatrist were included. Other studies have found that approximately half of people with learning disability receiving neuro-leptic medication and just over one-third of those

receiving antidepressants are under the review of a consultant psychiatrist (Emerson et al. 1998). In addition, independent housing providers were not included in the survey.

Despite these limitations, the survey demonstrated that at least 23%of the service’s dispersed housing network tenants were prescribed psychoactive medication. This is compa-rable with numbers cited in other community surveys (Branford 1994; Emersonet al.1998), although Kiernanet al.

(1995) found 48% of people were prescribed antipsychotic medication (PRN medication was included).

In common with other studies, these findings may suggest that prescribing of psychotropic medication is more common in dispersed housing settings than in family settings. However, the large proportion of the sample in dispersed housing is likely to have been caused, at least in part, by a lower response from CLDT members, and as a result of information being easier to access for people in dispersed housing. Moreover, CLDT staff are only in contact with a proportion of the learning disabled population at any given time, so are unlikely to be able to identify all people prescribed psychotropic medication.

The pattern of prescribing contrasts with other studies. These have shown that thioridazine (Branford 1994; Moly-neux et al. 1999) or chlorpromazine (Kiernan et al. 1995) were most commonly prescribed, and that haloperidol and zuclopenthixol were also regularly prescribed. None of these studies highlighted risperidone as being commonly prescribed, probably because it has only become available relatively recently. The rates of prescribing of antimuscar-inic medication are identical to findings in Leicestershire (Branford et al. 1995) – this may reflect the incidence of Parkinsonian side effects.

Polypharmacy

The levels of polypharmacy are also similar to those found in some other studies; for example 30% in three areas in the North West (Molyneux et al. 1999). Twenty-four people within our sample (44%) were prescribed more than one type of medication, compared with 35% in the Kiernan et al. (1995) study. Twelve people (22%) in our sample were prescribed more than one of the same type of neuroleptic; this compares with 23% (Molyneux et al. 1999), 22% (Kiernan et al. 1995) and 11% (Branford 1994).

under-estimate of levels of polypharmacy, national variations in prescribing patterns, or the community setting in our study. This indicates the continuing need to examine prescription patterns in different settings and to consider the setting where studies have been carried out. The levels of polypharmacy in these studies are of concern because of the potential consequences of polypharmacy.

Diagnosis

It is worrying to note the number of people prescribed such medication who appear not to have a mental health diagnosis. This may suggest that a diagnosis has not been made, documented, or communicated to staff. Alternat-ively, it may suggest that individuals are being prescribed psychotic medication to prevent behaviour which chal-lenges (for example, aggression, self-injury, insomnia), rather than addressing the causes of such behaviour. It may also reflect a reluctance to label people with a mental health diagnosis. Another study exploring the reasons why people with learning disabilities are prescribed psycho-tropic medication found that whilst 59% of medications were prescribed to treat the diagnosis for which the medication was intended, 20%were prescribed for reasons that did not match the accepted use of the medications (Young & Hawkins 2002) (see also Emersonet al. 1998).

Whereas it can be difficult to give correct diagnoses of mental health problems within the field of learning disabilities (Hogg et al. 1988; Kroese et al. 2001) and the very validity and reliability of mental health diagnoses has been challenged (e.g. Bentall 1993), it is worth noting that there is little evidence to support the long-term manage-ment of behaviours which challenge services with psych-otropic medication (for example, Branford 1996; Kiernan & Qureshi 1993). Indeed, it may reduce adaptive behaviour and interfere with learning (Aman 1984). Even when an individual does have a mental health diagnosis, medica-tion is not necessarily the treatment of choice, although it may form part of a broader treatment approach. Whilst the AAMR Expert Consensus Guidelines state that ‘psycho-tropic medication use should be based on a psychiatric diagnosis or specific behavioural-pharmacological hypo-thesis’ (Guideline 4, Rush & Frances 2000), they also emphasize the importance of appropriate behavioural and environmental interventions before the use of psychotropic medication. Robertson et al. (2003) found that whilst a large proportion of their sample was on anti-psychotic medication, few had written behavioural programmes for reduction of challenging behaviour. Future studies could usefully include reasons for prescribing medication, whilst audits should identify whether other interventions have been tried prior to, or in conjunction with, psychotropic medication.

Demographics

It may at first be surprising that so few people in the group between 20 and 29 years of age were prescribed psychotropic medication as it is a commonly held belief that the use of psychotropic medication reduces with age (as can be seen from the other age groups). However, when interpreting these results it should be remembered that most of the people in the sample were living in supported housing networks. People may not come into contact with such provision until they are older and family support breaks down. In addition, many people living within the networks have been resettled from long-stay institutions where some had spent many years. Thus people in the networks are older, on average, than in the general population.

Implications for practice

The importance of regular reviews of psychoactive medi-cation cannot be under-estimated both in terms of people receiving a correct dosage and the implications of suffering side effects of medication. The majority of people

prescribed psychotropic medication had medication

reviewed regularly, follow-up appointments were made with consultants, and information was clearly available from records kept as to when the medication was prescribed. This reflects a level of good practice. However, it is worrying that some of the people known to the service had not had reviews for over a year, and that for some people it was not known when the last review was. The findings from the survey have been shared within the service. A number of steps have been taken as a result as described below.

Medication reviews

Twenty people were referred to a learning disability

psychiatrist for a review of medication. Table 3

summarizes the results of these visits. The majority of

Table 3 Results of psychiatrist’s visits

n

Reduce/stop psychoactive medication* 8

Change medication 5

No change 4

Increase psychoactive medication 1

Alter means of administration (injection, not tablet) 1

Not seen 1

20

*Includes reductions in antipsychotics or antidepressants.

From one antipsychotic to another, or from an antidepressant to an

changes were attempts to reduce psychoactive medication, often with the aim of stopping medication, indicating good practice. There is only one example of increasing medication and this followed a failed attempt to alter timing of medication.

Improving guidelines and information

The survey has shown that information about a person’s medication and/or diagnosis may not be routinely and consistently recorded in their records. Guidelines should be included in a person’s care plan of how to address behaviours that challenge services, along with information about the medication a person is prescribed, the reason for this medication, potential side effects and frequency of medication reviews.

The need for ongoing audits

Clearly, such surveys can draw attention to the level of prescribing of psychoactive medication locally, and identify people whose medication needs to be reviewed. The service plans to incorporate whether people are receiving medica-tion reviews as part of the regular audits of standards within dispersed housing. However, this will not ensure that people living in a family setting, or in independently provided housing receive regular reviews; recording infor-mation about medication reviews in Health Action Plans would include these people.

Side effects to psychotropic medication are common and some are long-term (for example, tardive dyskinesia, tardive akathisia). A number of standard tools to monitor the side effects of psychotropic medication exist which could be used by services. These include the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (Andreasen 1989), the Liverpool University Neuroleptic Side Effects Rating Scale (Dayet al.

1995) and the nurse-administered ‘side-effect’ checklist (Jordanet al.2002).

Staff training and information provision

During the survey, some support staff expressed a wish to learn more about medication and their side-effects. It has been recommended that staff are aware of possible side-effects of medication to look out for. This could be done by recording such information as part of individ-uals’ care plans and/or Health Action Plans. Valuing People (Department of Health 2001) recommends that potential side effects are included in Health Action Plans. As some people are prescribed antimuscarinic medication to be administered as necessary to counter any side-effects of other medication, this can be particularly important. A seminar has been held and further training sessions are planned for employees, regarding the

pre-scribing and side-effects of psychotropic medication. The information needs of informal carers will also need to be addressed.

Appointments and reviews

Within dispersed housing people are usually supported to appointments by a support worker. Other studies have suggested that carers do not always know why antipsy-chotic medication has been prescribed (Kiernanet al.1995). It is essential that those supporting adults with learning disabilities to appointments have up-to-date knowledge of the person. This should include changes in behaviour and mental health since the last review, details of current and past medication (including how long it has been prescribed) and whether the person is showing any side effects to the medication. The objective team recommended that a form be devised to take to appointments to provide such informa-tion. Methods of meeting similar needs by family carers also require exploring.

Implications for future studies

This study had some methodological limitations which may have led to some biases and possible under-estima-tion of the problem of inappropriate medicaunder-estima-tion. How-ever, this reflects some of the difficulties of doing research in a service setting. The authors believe that the findings from the study are still useful. It is important that services are encouraged to carry out studies and report findings, even if this entails some compromise on scien-tific standards, in order to scrutinize and improve service provision and to highlight issues of concern to a wider audience.

The main stages of the study were carried out before the appointment of a researcher (MC) to support research within the service. A number of difficulties in terms of questionnaire design, sampling and auditing against expli-cit standards may have been avoided had methodological advice been sought earlier. It is important that other studies consider the impact on staff time of participating in research so that service research is feasible among the many other demands faced by practitioners.

The study has informed local service provision and demonstrated that levels of psychotropic medication may still be unacceptably high within learning disability services. Taken in the context of other work on this topic

it demonstrates the importance of future studies

Conclusions

This survey drew attention to the number of people with learning disabilities prescribed psychotropic medication, despite a body of work suggesting that use of such medica-tion may not always be beneficial. However, the survey also highlighted areas of good practice, has informed a number of local service developments, and resulted in reviews for individuals, which have generally led to steps to reduce medication. Ongoing audits and monitoring of side effects will be beneficial, whilst more robust information systems would facilitate future audits and lead to more accurate information. There are a number of methodological lessons from this study that could inform future audits and research.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the MLDP staff who were members of the objective group at various times. In particular, thanks are due to Hamish Kemp, Michael Hughes and Lisa Jones for their roles in literature searching, survey planning and administration, and data entry. The authors would also like to thank all those who took the time to complete question-naires, and to Anne Francis for collating information about the medication reviews from records.

References

Aman M.G. (1984) Drugs in learning and mentally retarded persons.Adv Human Psychopharmocol,3: 121–63.

Andreasen N. (1989) Scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS).Br J Psychiatry,155(Suppl. 7), 53–8.

Bentall R.P. (1993) Deconstructing the concept of schizophrenia.

Journal of Mental Health,2: 223–38.

Branford D. (1994) A study of the prescribing for people with learning disabilities living in the community and in National Health Service Care.J Intellect Disabil Res,38: 577–86. Branford D. (1996) Factors associated with the successful or

unsuccessful withdrawal of antipsychotic drug therapy pre-scribed for people with learning disabilities.J Intellect Disabil Res,

40: 322–9.

Branford D., Collacott R.A. & Thorp C. (1995) The prescribing of neuroleptic drugs for people with learning disabilities living in Leicestershire.J Intellect Disabil Res,39: 495–500.

British Medical Association (2001)British national formulary. London, BMJ Books.

Brylewski J. & Duggan L. (2004) Antipsychotic medication for challenging behaviour in people with learning disability (Coch-rane Review). In:The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2004. Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clarke D.J., Kelley S., Thinn K. & Corbett J.A. (1990) Psychotropic drugs and mental retardation:1. Disabilities and the prescription of drugs for behaviour and for epilepsy in three residential settings.J Ment Defic Res,34: 385–95.

Cohen H., Loewenthal U., Matar M. & Kotler M. (2001) Association of autonomic dysfunction and clozapine: heart rate variability

and risk for sudden death in patients with schizophrenia on long-term psychotropic medication.The Brit J Psychiatry,179: 167–71. Dalvi M., Thalayasingam S.P. & George G.R. (2003) Audit on high

dose antipsychotic medication in three tertiary services for people with learning disability.Brit J Dev Disabil,49(97, Pt 2), 117–24.

Day J.C., Wood G., Dewey M. & Bentall R. (1995) A self-rating scale for measuring neuroleptic side effects: validation in a group of schizophrenic patients.Br J Psychiatry,166: 650–3.

Department of Health (2001)Valuing people: a new strategy for

learning disability for the 21st century. London, Department of

Health.

Didden R., Duker P.C. & Korzilius H. (1997) Meta-analytic study on treatment effectiveness for problem behaviours with individuals who have mental retardation.Am J Ment Retard,101: 387–99. Duggan L. & Brylewski J. (2004) Antipsychotic medication for those

with both schizophrenia and learning disability (Cochrane Review). In:The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2004. Chichester, UK, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Emerson E., Hatton C., Caine A. & Bromley J. (1998)Clinical

psychology and people with intellectual disabilities. Chichester, Wiley

Series in Clinical Psychology.

Frassati D., Tabib A., Lachaux B., Giloux N., Dale´ry J. et al. (2004) Hidden cardiac lesions and psychotropic drugs as a possible cause of sudden death in psychiatric patients: a report of 14 cases and review of the literature.Can J Psychiatry,49: 100–5. Hogg J., Moss S. & Cooke D. (1988)Ageing and mental handicap.

London, Croom Helm.

Jenkins R. (2000) Use of psychotropic medication in people with a learning disability.Brit J Nurs,9: 844–50.

Jordan S., Tunnicliffe C. & Sykes A. (2002) Minimizing side-effects: the clinical impact of nurse-administered ‘side-effect’ checklists.

J Adv Nurs,37: 155–65.

Kiernan C. & Qureshi H. (1993) Challenging behaviour. In: Kiernan C., editor.Research into practice? Implications of research on the

challenging behaviour of people with learning disabilities.

Kidder-minster, British Institute of Learning Disabilities: 53–87. Kiernan C., Reeves D. & Alborz A. (1995) The use of antipsychotic

drugs with adults with learning disabilities and challenging behaviour.J Intellect Disabil Res,39: 263–74.

Kroese B.S., Dewhurst D. & Holmes G. (2001) Diagnosis and drugs: help or hindrance when people with learning disabilities have psychological problems?Brit J Learn Disabil,29: 26–33. Miller B.F. & Brackman Keane C. (1987)Encyclopaedia and

dictionary of medicine, nursing and allied health. Philadelphia:

WB Sounders.

Molyneux, Emerson E. & Caine A. (1999) Prescription of psycho-tropic medication to people with intellectual disabilities in primary health care settings.J Appl Res Intellectual Disabil,12: 46–57.

Osman B. (2000) Learning disabilities and the risk of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. In: Greenhill L., editor.

Learning disabilities: implications for psychiatric treatment.Review of

psychiatry series, 19: 5.

Rush A.J. & Frances A. (2000) Expert consensus guideline series: treatment of psychiatric and behavioral problems in mental retardation.Am J Ment Retard,105: 159–228.

Straus S.M.J.M., Bleumink G.S., Dieleman J.P., van der Lei J., ’t Jong G.W., et al. (2004) Antipsychotics and the risk of sudden cardiac death.Arch Intern Med,164: 1293–7.

Young A.T. & Hawkins J. (2002) Psychotropic medication pre-scriptions: an analysis of the reasons people with mental retardation are prescribed psychotropic medication.J Dev Physical