CONFLICT MANAGEMENT AND

INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION

In the glob ally inter con nec ted world, conflicts often arise as a result of tensions between differ ent cultural percep tions and diverse social pref er ences. Effectively managing conflicts and harmon iz ing inter cul tural rela tion ships are essen tial tasks of inter cul tural commu nic a tion research.

This book seeks to find effect ive inter cul tural conflict manage ment solu tions by bring ing together a group of leading inter na tional schol ars from differ ent discip lines to tackle the problem. Consisting of two parts, this book covers major theor et ical perspect ives of conflict manage ment and harmony devel op ment in the first and conflict manage ment and harmony devel op ment in differ ent cultural contexts in the second. Integrating the latest work on conflict manage ment and inter cul tural harmony, Conflict Management and Intercultural Communication takes an inter dis cip lin ary approach, adopts diverse perspect ives and provides for a wide range of discus sions. It will serve as a useful resource for teach ers, research ers, students and profes sion als alike.

Xiaodong Dai is Associate Professor at the Foreign Languages College of Shanghai Normal University, China. He currently serves as the vice pres id ent of the China Association for Intercultural Communication (CAFIC ).

CONFLICT

MANAGEMENT AND

INTERCULTURAL

COMMUNICATION

The Art of Inter cul tural Harmony

First published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, N Y 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa busi ness © 2017 selec tion and edit or ial matter, Xiaodong Dai and Guo-Ming Chen; indi vidual chapters, the contrib ut ors

The right of Xiaodong Dai and Guo-Ming Chen to be iden ti fied as the authors of the edit or ial mater ial, and of the authors for their indi vidual chapters, has been asser ted in accord ance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprin ted or repro duced or util ised in any form or by any elec tronic, mech an ical, or other means, now known or here after inven ted, includ ing photo copy ing and record ing, or in any inform a tion storage or retrieval system, without permis sion in writing from the publish ers.

Trademark notice: Product or corpor ate names may be trade marks or registered trade marks, and are used only for iden ti fic a tion and explan a tion without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A cata logue record for this book is avail able from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been reques ted.

ISBN: 978-1-138-96283-5 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-138-96284-2 (pbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-26691-6 (ebk)

Typeset in Bembo

CONTENTS

List of figures viii

List of tables x

Notes on contrib ut ors xi Preface xiv

Introduction 1

Xiaodong Dai and Guo-Ming Chen

PART I

Perspectives on the study of inter cul tural conflict

manage ment 11

1 Moving from conflict to harmony: the role of dialogue in

bridging differ ences 13

Benjamin J. Broome

2 A dialo gic approach to inter cul tural conflict manage ment

and harmo ni ous rela tion ships: dialogue, ethics and culture 29

Yuxin Jia and Xue Lai Jia

3 Between conflict and harmony in the human family: Asia centri city and its ethical imper at ive for inter cul tural

commu nic a tion 38

vi Contents

4 Constituting inter cul tural harmony by design think ing: conflict manage ment in, for and about diversity and

inclu sion work 66

Patrice M. Buzzanell

5 The devel op ment of inter cul tur al ity and the manage ment

of inter cul tural conflict 85

Xiaodong Dai

6 Transforming conflict through commu nic a tion and

common ground 98

Beth Bonniwell Haslett

7 Conflict face- nego ti ation theory: track ing its

evol u tion ary journey 123

Stella Ting-Toomey

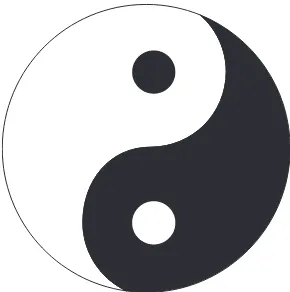

8 The yin and yang of conflict manage ment and resol u tion:

a Chinese perspect ive 144

Guo-Ming Chen

9 Rethinking cultural iden tity in the context of glob al iz a tion: compar at ive insights from the Kemetic and

Confucian tradi tions 155

Jing Yin

PART II

Conflict manage ment in cultural contexts 175

10 Intercultural conflict and conflict manage ment in South

Africa as depic ted in indi gen ous African liter ary texts 177

Munzhedzi James Mafela and Cynthia Danisile Ntuli

11 Cultural orient a tions and conflict manage ment styles with peers and older adults: the indir ect effects through

filial oblig a tions 194

Yan Bing Zhang, Chong Xing and Astrid Villamil

12 Intercultural commu nic a tion manage ment profes sion als

in the Japanese linguistic and cultural envir on ment 210

13 The discurs ive construc tion of iden tit ies and conflict manage ment strategies in parent–child conflict narrat ives

written by Chinese univer sity students 221

Xuan Zheng and Yihong Gao

14 A Chinese model of construct ive conflict manage ment 239

Yiheng Deng and Pamela Tremain Koch

15 Conflicts in an inter na tional busi ness context: a theor et ical

analysis of inter per sonal (pseudo)conflicts 254

Michael B. Hinner

16 Intercultural conflicts in transna tional mergers

and acquis i tions: the case of a failed deal 278

Juana Du and Ling Chen

17 Intercultural chal lenges in multina tional corpor a tions 295

Alois Moosmüller

FIGURES

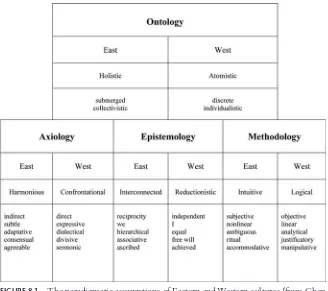

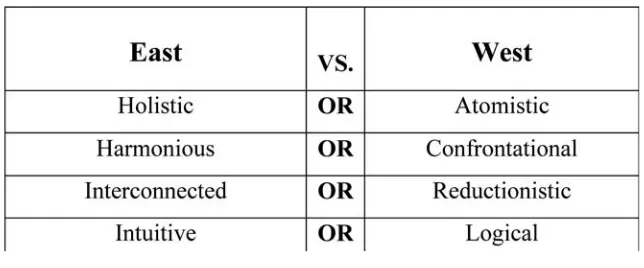

8.1 The paradig matic assump tions of Eastern and Western cultures 146 8.2 The either- or view of paradig matic assump tions between

East and West 149

8.3 The continuum view of cultural values based on

paradig matic assump tions 149 8.4 Similarities and differ ences of cultural values between nations 150

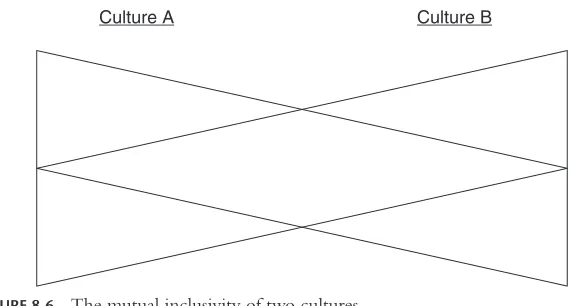

8.5 The mutual exclus iv ity of two cultures 150

8.6 The mutual inclus iv ity of two cultures 151

8.7 The tai chi model of conflict manage ment 152

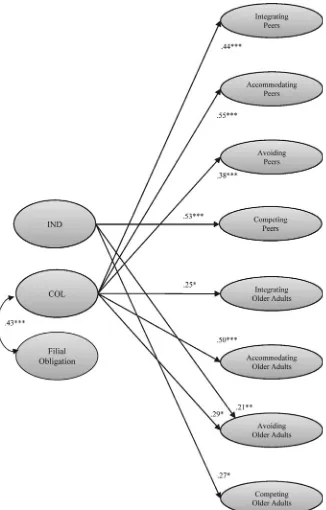

11.1 Unstandardized signi fic ant para meter estim ates: IN D and COL predict ing peer and intergen er a tional conflict

manage ment styles 202

11.2 Significant factor correl a tions of the four conflict styles in the

peer and older adult condi tions 203 11.3 Unstandardized signi fic ant para meter estim ates: indir ect effects

of COL on the integ rat ing, accom mod at ing and avoid ing styles

in the intergen er a tional condi tion 204

12.1 The number of foreign tour ists in Japan 211

12.2 Three import ant factors contrib ut ing to Japanese people’s

aware ness of inter na tion al iz a tion 213

12.3 A can- do list for the ICM-AP and the ICMP 214

12.4 The table of contents 216

12.5 The flow of the qual i fic a tions for the ICM-AP and the ICMP 217

12.6 The renov a tion of street signs in Tokyo 218

13.1 Distribution of actual strategies 229

13.2 Distribution of proposed strategies 229

14.2 Components of Chinese culture that influ ence conflict beha vi ors 245 14.3 Model of cooper at ive conflict manage ment with Chinese 246 15.1 The inter re la tion ship of cogni tion, meta cog ni tion, social

TABLES

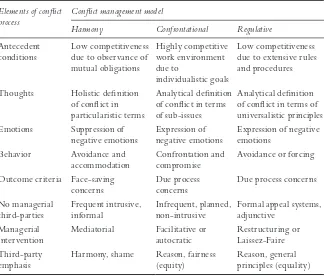

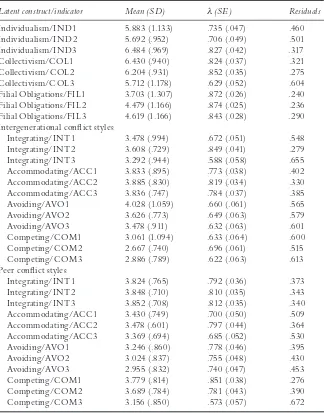

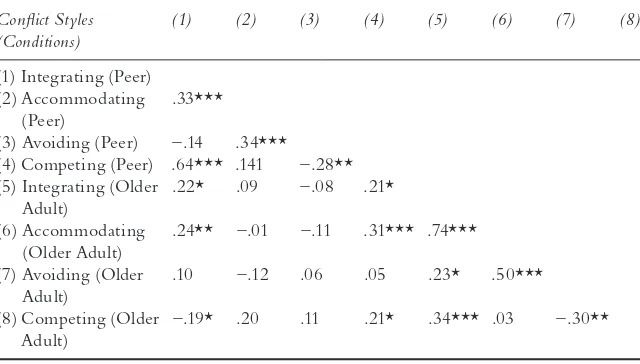

6.1 Three cultural models of conflict manage ment 105 11.1 Descriptive stat ist ics, stand ard ized factor load ings, stand ard errors,

and resid uals for the parceled indic at ors of the latent constructs 201 11.2 Factor correl a tions among the conflict styles in the peer and

older adult condi tions 203

13.1 Demographic inform a tion of parti cipants 224

13.2 Triggering event of conflict 226

13.3 Transitivity system 230

13.4 Occurrences of trans it iv ity processes in actual strategies 231 13.5 Occurrences of trans it iv ity processes in proposed strategies 231 13.6 Percentage of trans it iv ity processes in domin at ing,

CONTRIBUTORS

Benjamin J. Broome is Professor in the Hugh Downs School of Human Communication at Arizona State University.

Patrice M. Buzzanell is Distinguished Professor in the Brian Lamb School of Communication and the School of Engineering Education at Purdue University. She is the past pres id ent of the International Communication Association (ICA) and the pres id ent of the Council of Communication Associations (CCA) and the Organization for the Study of Communication, Language and Gender (OSCLG). Guo-Ming Chen is Professor of Communication Studies at the University of Rhode Island. He is the found ing pres id ent of the Association for Chinese Communication Studies (ACCS). He served as the exec ut ive director of the International Association for Intercultural Communication Studies (IAICS) for six years and is currently the pres id ent of the asso ci ation.

Ling Chen is Professor in the School of Communication at Hong Kong Baptist University. She was the editor- in-chief of Management Communication Quarterly and the asso ci ate editor of Communication Theory.

Xiaodong Dai is Associate Professor at the Foreign Languages College of Shanghai Normal University. He currently serves as the vice pres id ent of the China Association for Intercultural Communication (CAFIC ).

xii Contributors

Juana Du is Assistant Professor and the program head of the Master of Arts in Intercultural and International Communication on- campus program at the School of Communication and Culture at Royal Roads University.

Yihong Gao is Professor and the director of research at the Institute of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics in the School of Foreign Languages at Peking University. She is also the vice pres id ent of the China English Language Education Association (CELEA) and has served as the pres id ent of the Association of Chinese Sociolinguistics (ACS).

Beth Bonniwell Haslett is Professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Delaware. She has published four books and more than thirty articles and book chapters, and has presen ted over sixty papers at regional, national and inter na tional confer ences.

Michael B. Hinner is Professor at the Freiberg University of Mining and Technology. He is the editor of the book series Freiberger Beiträge zur Interkulturellen und Wirtschaftskommunikation (Freiberg Contributions to Intercultural and Business Communication).

Xue Lai Jia is Associate Professor of Intercultural Communication in the School of Foreign Languages at the Harbin Institute of Technology.

Yuxin Jia is Professor of Sociolinguistics, Applied Linguistics and Intercultural Communication at the Harbin Institute of Technology. He is a past pres id ent of the International Association for Intercultural Communication Studies (IAICS) and the China Association for Intercultural Communication (CAFIC ).

Pamela Tremain Koch is Adjunct Professor at the Seidman College of Business, Grand Valley State University. Her research fields are cross- cultural lead er ship and conflict manage ment.

Munzhedzi James Mafela is Professor of African Languages at the University of South Africa. He was a guest editor of the Southern African Journal of Folklore Studies in 2011 and the scientific editor of the same journal in 2013.

Yoshitaka Miike is Associate Professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Hawaii at Hilo and Fellow at the Molefi Kete Asante Institute for Afrocentric Studies. He is past chair of the International and Intercultural Communication Division (IICD) of the National Communication Association (NCA).

inter cul tural trainer and consult ant. He has done extens ive research on German– Japanese and American–Japanese collab or a tion in multina tional corpor a tions. Cynthia Danisile Ntuli is Associate Professor at the University of South Africa in the Department of African Languages.

Yuko Takeshita is Professor of English and Intercultural Communication in the Department of International Communication at Toyo Eiwa University. She serves as the director of the Global Human Innovation Association. She also works as the managing editor of Asian Englishes.

Stella Ting-Toomey is Professor of Human Communication Studies at California State University (CSU ), Fullerton. She was the 2008 recip i ent of the 23-campus- wide CSU Wang Family Excellence Award and the 2007–2008 recip i ent of the CSU-Fullerton Outstanding Professor Award in recog ni tion for her super lat ive teach ing, research and service.

Astrid Villamil is Assistant Teaching Professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Missouri. Her research focuses on diversity in higher educa tion and inter cul tural/inter group processes in organ iz a tional contexts.

Chong Xing is a doctoral candid ate in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of Kansas. His research interests include examin ing indi vidual commu nic at ive prac tices in various inter group processes and study ing romantic rela tion ship initi ation.

Jing Yin is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Communication at the University of Hawaii at Hilo and Fellow at the Molefi Kete Asante Institute for Afrocentric Studies. She won a Top Paper Award from the International and Intercultural Communication Division of the National Communication Association (NCA).

Yan Bing Zhang is Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Studies at the University of Kansas. She studies commu nic a tion, conflict manage ment and inter group rela tions with a partic u lar focus on age and cultural groups.

PREFACE

As one of the oldest concepts regard ing human beha vi ors, conflict manage ment has been studied by schol ars in differ ent academic discip lines for many years. The concept has remained signi fic ant in the contexts of both human inter ac tion and schol arly research as human society has progressed into the 21st century. The new century, which has thus far been char ac ter ized by a process of glob al-iza tion that has been accel er ated by the rapid devel op ment of new tech no l ogy, demands a global connectiv ity that thrives on intens ive compet i tion and cooper a tion between people from differ ent cultures. It has there fore never been more neces sary to situate the study of conflict manage ment in a global context.

In response to this dire need to place the study of con flict manage ment in a global context, the fourth bien nial International Conference of Intercultural Communication, which was sponsored by Shanghai Normal University and which took place from December 28 to December 29, 2014, focused on the theme of conflict manage ment and inter cul tural harmony. After the confer ence, 17 papers from a pool of more than 150 present a tions were selec ted to be included in this book. The authors of these papers are from differ ent cultures and academic discip lines, and their papers deal with differ ent aspects of conflict manage ment, examin ing the concept from various research perspect ives and within diverse cultural contexts. The diversity and rich ness of these papers reflect the need to study conflict manage ment as a global phenomenon.

this project. And finally, we would like to thank the edit or ial staff at Routledge, partic u larly Ms. Yongling Lam, for their assist ance with the public a tion of this book.

INTRODUCTION

Xiaodong Dai and Guo-Ming Chen

We are living in a glob al iz ing world that is char ac ter ized by unity in diversity (Chen & Starosta, 2004). With the strength en ing of global inter con nectiv ity and inter de pend ence, conflicts frequently arise due to tensions stem ming from differ ent cultural percep tions, dispar ate social pref er ences or diverse value orien-t a orien-tions. While effecorien-t ive manage menorien-t of a conflicorien-t opens up oppor orien-tun iorien-t ies for people to learn more about others and make a joint effort to explore better patterns of commu nic a tion, conflict misman age ment often leads to escal ated hostil ity and damaged rela tion ships (Ting-Toomey & Oetzel, 2001). How to manage conflicts construct ively and achieve harmo ni ous inter ac tion is the prin-cipal problem faced by inter cul tural commu nic a tion schol ars. Although they have invest ig ated conflict manage ment in inter na tional busi ness nego ti ation and developed useful analyt ical models, few of them have been able to synthes ize multiple perspect ives and address how inter cul tural harmony can be achieved in differ ent cultural contexts. This book attempts to improve the situ ation by bring ing together leading inter na tional schol ars from differ ent discip lines to tackle the problem. It aims to integ rate the latest work on conflict manage ment and inter cul tural commu nic a tion, and further provide a useful source of m a tion for students, instruct ors, research ers and prac ti tion ers in inter cul tural or global commu nic a tion and related areas. Although there are numer ous prob lems involved in conflict manage ment, the present volume only focuses on two crucial aspects of the issue, namely, perspect ives on the study of inter cul tural conflict manage ment and conflict manage ment in diverse cultural contexts.

Perspectives on the study of inter cul tural conflict manage ment

2 Xiaodong Dai and Guo-Ming Chen

A conflict may appear at the inter per sonal or inter group level and involves polit-ical, economic or cultural factors. The complex ity of the problem demands inter-cul tural commu nic a tion schol ars to address it from differ ent perspect ives. Only through the synthesis of differ ent perspect ives can a more complete picture of inter cul tural conflict be presen ted.

In recent decades, schol ars have indeed approached inter cul tural conflict from diverse perspect ives and developed useful theor ies and models. For example, Ting-Toomey (1988, 2005) has examined conflict from the face- nego ti ation perspect ive and has claimed that people in all cultures try to nego ti ate face in order to main tain a posit ive self- image in inter ac tion. While high power distance and collect iv istic cultural members tend to show more concern for other- face and mutual- face, low power distance and indi vidu al istic cultural members tend to show more concern for self- face. In managing a conflict, collect iv ists usually adopt avoid ance, third party medi ation, and integ ra tion strategies, and indi vidu-al ists tend to employ direct confront a tion and domin a tion strategies. Drawing on social iden tity theory, Worchel (2005) developed a model of peace ful coex ist-ence. He argued that it is not group iden tity in itself but the perceived threat to group iden tity and secur ity from another group that is the root of inter cul tural conflict. The recog ni tion of others’ right to exist, curi os ity and interests in their cultures and a will ing ness to engage in a cooper at ive inter ac tion with them are the keys to peace ful coex ist ence. Moreover, Moran, Abramson and Moran (2014) have argued that effect ive inter cul tural conflict manage ment is based on five steps: (1) describ ing the conflict in a way that is under stood in both cultures; (2) examin ing the problem from both cultural lenses; (3) identi fy ing the causes from both cultural perspect ives; (4) solving the conflict through syner gistic strategies; and (5) determ in ing whether the solu tion works inter cul tur ally.

When analyz ing an inter per sonal or inter group conflict, most schol ars have emphas ized the influ ence of cultural values on conflict beha vi ors and the cross- cultural compar ison of conflict styles. Some schol ars have examined how cultural diversity is managed in organ iz a tions, but they have tended to focus on a single level of inter cul tural conflict (e.g. Oetzel, Dhar & Kirschbaum, 2007). Meanwhile, others have tackled the issue from the perspect ive of a specific culture. For example, Chen (2001, 2009, 2014) has developed a theory of harmony to deal with conflict from the Chinese cultural perspect ive. For future research, we suggest that schol ars further explore the concept of inter cul tural conflict with an approach that considers the inter act ive process of conflict manage ment and the ethics of conflict nego ti ation and that adopts a multi level perspect ive.

will not satis fact or ily resolve the problem. Although taking a multi level perspect ive is chal len ging for schol ars, it can provide them with a more compre-hens ive under stand ing of the issue and help them reach an effect ive way of dealing with inter cul tural conflict (Oetzel et al., 2007).

In many cases, inter cul tural conflicts are diffi cult to resolve, their solu tions taking a great deal of time and energy to nego ti ate. Even once a solu tion has been reached, other conflicts may emerge if one party feels that it is being treated unfairly (Worchel, 2005). Conflict nego ti ation ethics is there fore an integ ral part of the inter cul tural conflict manage ment process. The ethics of inter cul tural conflict nego ti ation provide people from differ ent cultures with mutu ally shared moral norms and prin ciples that can be used to guide their mutual inter ac tion. Moral prin ciples such as human dignity, equal ity, justice, non-vi ol ence, sincer ity, toler ance and respons ib il ity are condu cive to conflict resol u tion and achieve lasting outcomes (Chen, 2015; Christian, 2014; Ojelabi, 2010).

Conflict manage ment in cultural contexts

Cultural value defines what is right, equal, fair and safe, and what is wrong, unequal, unjust, unfair and danger ous (Marsella, 2005). It shapes the way we perceive the world and the way we respond to social reality (Chen, Ryan & Chen, 2000). Culture is a key determ in ant for conflict manage ment. ing how a conflict is managed in diverse cultural contexts allows us to learn a coun ter part’s commu nic a tion beha vi ors, so that inter cul tural harmony can be construc ted in inter ac tion.

Over the years, schol ars have widely invest ig ated conflict beha vi ors in various cultural contexts. For example, Kozan and Ergin (1998) examined the differ ences in pref er ence for third party help in conflict manage ment between Americans and Turks. They found that Turkish people were more collect iv istic and preferred third party medi ation in conflict manage ment; they also found that this tend ency was partic u larly strong with Turkish women. Siira, Rogan and Hall (2004) compared conflict manage ment between Americans and Finns. The authors found that Americans and Finns had a similar pref er ence for the use of non- confront a tional strategies, but Finns used more solu tion- oriented strategies and Americans used more controlling beha vi ors. Chen (2010) discussed conflict manage ment strategy in Chinese state- owned enter prises. He pointed out that the Chinese emphas ize harmony in social commu nic a tion by apply ing accom-mod a tion, collab or a tion and avoid ance strategies in conflict resol u tion, and that older people tended to use these strategies more often.

4 Xiaodong Dai and Guo-Ming Chen

intra cul tural diversity; situ ational factors; non-Western cultural compar is ons; and nego ti ation processes.

First, Hofstede’s theory presents a useful frame work for identi fy ing cultural differ ences and the root of inter cul tural conflicts, but it does not consider intra-cul tural vari ations. Within a nation in which co- intra-cultural groups exist, it is neces-sary to take the issues of diversity into account in order to manage conflict success fully. For example, when commu nic at ing with a subor din ate, Mexican Americans place less emphasis on other- face and are more likely to use aggress ive strategies than European Americans. However, when commu nic at ing with a super ior, Mexican Americans place more emphasis on other- face and are more likely to use obli ging and integ rat ing strategies (Tata, 2000). In China, people are gener ally restrained when it comes to solving inter per sonal conflicts, but Northerners are more emotional and aggress ive than Southerners (Yu, 2013).

Second, situ ational factors such as ingroup/outgroup member ship and conflict sali ence also influ ence inter cul tural conflict manage ment (Ting-Toomey & Oetzel, 2003). For instance, Japanese are direct in express ing personal opin ions when inter act ing with ingroups, but they are highly indir ect when inter act ing with outgroups. Moreover, Chinese tend to be polite when face is being main-tained in a conflict situ ation but may become fiercely confront a tional when it is lost (Chen, 2010).

Third, world cultures are inter re lated, espe cially in our glob al iz ing society. Merely compar ing Western and non-Western cultures reflects the bias of Eurocentrism (Miike, 2010). To explore the differ ences between non-Western cultures and between Western cultures respect ively is to allow people to reach a better under stand ing of conflict manage ment. For example, while Japanese and Brazilians are both collect iv istic, Brazilians use emotional expres sions to main-tain rela tion ships and Japanese negat ively view overt emotional expres sions as stand ing in the way of rela tional harmony (Graham, 1985). Kozan (1989) also found that, when managing a conflict with subor din ates, Turkish managers use the collab or at ing style more than the forcing style and that Jordanian managers use the collab or at ing style more than the comprom ising style.

inter cul tural conflict nego ti ation: primary orient a tion, situ ational and rela tion-ship bound ary, conflict process and conflict compet ence. These inter re lated factors work together to bring about product ive and satis fact ory outcomes, which attest to the fact that inter cul tural conflict manage ment is a dynamic process.

Overview of the book

This volume has two parts. The first part deals with conflict manage ment from multiple perspect ives, and the second part explores conflict manage ment in diverse cultural contexts. The first part begins with three chapters that address conflict manage ment ethics; the follow ing six chapters explore conflict manage-ment from culture- general and culture- specific approaches.

In the first chapter, Benjamin J. Broome explores a viable way to bring harmony to our conflic tual world. According to Broome, conflict is part of the harmon iz ing process and dialogue provides an import ant means to manage it. By bring ing together indi vidu als with varying perspect ives into a safe place, differ ent views are artic u lated and oppor tun it ies for mutual learn ing are created. Thus, the inher ent tension between self and other can be product ively managed. When the issues are fully examined and when all voices are heard, it becomes possible to synthes ize differ ences and work toward a state of inter cul tural harmony.

In the second chapter, Yuxin Jia and Xue Lai Jia present a dialo gic approach to inter cul tural conflict by explor ing how commu nic a tion ethics works in the process of conflict manage ment. The authors argue that build ing up a sound dialo gic ethics is central to reach ing conflict resol u tion and inter cul tural harmony. While modern ethics emphas izes the self, post mod ern ethics emphas izes the other. The modern perspect ive may lead to a dicho tomy between self and other, whereas the post mod ern perspect ive may suffer from the problem of “all for the other,” which may result in a depend ent rela tion ship between self and other. The dialo gic approach is a prefer able altern at ive to both the modern and post mod ern approaches. It incor por ates the concern for self and the concern for the other. This approach is best exem pli fied by Confucian virtue known as ren, which offers a viable way to manage conflict in a multi cul tural world.

In the third chapter, Yoshitaka Miike approaches inter cul tural conflict from the perspect ive of Asiacentricity. He argues that center ing our own culture and enga ging in ethical commu nic a tion promote dialogue across cultures and pave the way for inter cul tural harmony. Based on Asiacentricity, Miike proposes five ethical prin ciples for harmo ni ous inter cul tural rela tion ships, namely, recog ni tion and respect, reaf firm a tion and renewal, iden ti fic a tion and indebted ness, ecology and sustain ab il ity, and rooted ness and open ness. These ethical prin ciples enable people to appre ci ate both parties’ cultures and thus bring about unity to the global community.

6 Xiaodong Dai and Guo-Ming Chen

a wicked and complex problem that defies a rational approach. Buzzanell argues that it requires design think ing and a constitutive approach to effect ively manage the conflict between diversity and inclu sion.

In the fifth chapter, Xiaodong Dai addresses inter cul tural conflict manage-ment from the perspect ive of inter cul tur al ity. According to Dai, in order to effect ively manage an inter cul tural conflict people need to examine the inter-act ive process of inter cul tur al ity devel op ment, which is a process through which a possible means of harness ing inter cul tural tension can be obtained. Interculturality not only cultiv ates a posit ive atti tude toward cultural diversity, but also fosters an inter cul tural perspect ive that facil it ates joint actions in inter cul tural conflict manage ment.

In the sixth chapter, Beth Bonniwell Haslett proposes a new approach to conflict manage ment. Because most schol ars focus on the use of differ ent conflict styles, how the devel op ment of common ground serves to manage inter cul tural conflict deserves further invest ig a tion. Haslett posits that honor ing face is an import ant element in the process of inter cul tural conflict manage ment. Commonly shared values such as respect, trust, empathy, plur al ism, open ness and equal ity are essen tial compon ents of the univer sal face, which can be employed to broaden the way that conflict manage ment is examined in future research.

In the seventh chapter, Stella Ting-Toomey reviews the evol u tion ary process of her conflict face- nego ti ation theory (FNT). FNT is based on the studies of face carried out by Hsien Chin Hu (1944), Erving Goffman (1955) and Penelope Brown and Stephen Levinson (1987). The theory stip u lates cultural, indi vidual and situ ational factors that shape conflict beha vi ors in inter ac tion. The first version of FNT emphas izes the func tional link of Hall’s high- context and low- context cultural schema to conflict styles. The second version focuses on how indi vidu al ism and collect iv ism affect conflict styles. The third version further deals with indi vidual level factors regard ing the face concern and conflict styles, and also addresses the issue of conflict compet ence. According to Ting-Toomey, schol ars need to further examine complex situ ational and iden tity issues in the study of inter cul tural conflict manage ment in order to expand the scope of FNT.

In the eighth chapter, Guo-Ming Chen approaches conflict manage ment from the Chinese perspect ive. Chen argues that commu nic a tion is contex tu ally depend ent and that each culture has its own unique way of managing conflict. In light of Chinese philo sophy, conflict should be treated as a holistic system which is formed by the dynamic and dialect ical inter ac tion between the two parties of yin and yang. Although each party possesses its own iden tity, the iden tity cannot be fully developed indi vidu ally. When a conflict arises, the two parties should be treated as an inter re lated whole, so that the conflict can be construct ively managed and unity in diversity can be attained.

cultural partic u lar it ies and thereby devel ops a sense of mean ing ful exist ence. In order to become a global citizen, people need to be firmly rooted in their cultural tradi tions, but at the same time they must also be open to other cultures. Yin contends that it is imper at ive to seek an approach that allows schol ars to concep-tu al ize culconcep-tural iden tity in its full complex ity, a process which can be informed by both Kemetic and Confucian tradi tions.

The second part of this volume (Chapters 10–17), as mentioned above, deals with conflict manage ment in differ ent cultural contexts. Conflict manage ment is first invest ig ated in the context of South Africa, the United States, Japan and China, and it is then examined in the context of inter na tional busi ness and multina tional corpor a tions. In the tenth chapter, Munzhedzi James Mafela and Cynthia Danisile Ntuli examine how conflicts arise in intereth nic commu nic a-tion and how they are managed so as to achieve inter cul tural harmony. They find that White people in South Africa tend to devalue the local culture and that their Eurocentric bias often leads to the problem of inter cul tural conflict. They also point out that strategies such as refrain ing, persua sion, giving in, avoid ance, collab or at ing, comprom ising and accom mod a tion are effect ive ways of getting people from differ ent cultures to live in a state of peace ful coex ist ence.

In the elev enth chapter, Yan Bing Zhang, Chong Xing and Astrid Villamil analyze the pref er ence of conflict manage ment styles among American young adults. They find that cultural orient a tions shape people’s conflict manage ment style. While young adults tend to use more integ rat ing and compet ing styles with adults their peers, they tend to use more accom mod at ing and avoid ing styles with older adults. For peer conflicts, integ ra tion is the most prefer able style and avoid-ance is the least prefer able style. For intergen er a tional conflicts, however, the most prefer able style is accom mod a tion, and compet i tion is the least prefer able style.

In the twelfth chapter, Yuko Takeshita discusses the role of inter cul tural commu nic a tion manage ment profes sion als in Japan. Despite the devel op ment of glob al iz a tion in Japanese society, people have few oppor tun it ies to prac tice inter-cul tural commu nic a tion and often encounter linguistic and inter-cultural prob lems when inter act ing with foreign ers. Intercultural commu nic a tion manage ment profes sion als play an import ant role in helping their fellow citizens manage inter-cul tural conflict and create new busi ness oppor tun it ies.

In the thir teenth chapter, Xuan Zheng and Yihong Gao invest ig ate Chinese parent–child conflict manage ment strategies. Based on discurs ive evid ence, they find that among the five prefer able strategies for Chinese students dealing with this type of conflict—integ rat ing, comprom ising, obli ging, domin at ing and avoid ing— domin at ing and avoid ing rank highest. Zheng and Gao also find that the strategy of artic u lat ing is favored more by university students. The students use it to construct an inde pend ent self and develop an equal rela tion ship with their parents.

8 Xiaodong Dai and Guo-Ming Chen

harmony, face, guanxi (lit. rela tion ships) and power are the central values of Chinese culture. Strategies such as construct ive confront a tion, open and direct discus sion, seeking hard facts, resort ing to off- line talk, and turning to a third party of higher author ity for inter ven tion are effect ive ways for Chinese to manage conflict.

In the fifteenth chapter, Michael B. Hinner analyzes inter cul tural conflict manage ment in the context of inter na tional busi ness. Although English is used as a lingua franca in inter na tional busi ness commu nic a tion, misun der stand ings and inter cul tural conflicts often occur because of differ ing cultural back grounds. Hinner proposes five key factors—iden tity, culture, percep tion, self- disclos ure and trust—that shape the commu nic at ive process in inter cul tural conflict manage ment. The five factors will help people better perceive and manage misper cep tion and misun der stand ing, which often lead to inter cul tural conflict in the context of inter na tional busi ness trans ac tions.

In the sixteenth chapter, Juana Du and Ling Chen conduct a case study on inter cul tural conflict manage ment in transna tional mergers and acquis i tions. They find that cultural differ ences affect inter na tional busi ness commu nic a tion. The poor manage ment of misun der stand ings may lead to inter cul tural conflict. Misunderstanding and subsequent inter cul tural conflict can lead to failed busi-ness acquis i tions. Du and Chen suggest that corpor a tions need to engage each other in open dialogue in order to develop cultur ally appro pri ate commu nic a tion strategies that will allow acquis i tions to proceed without issue.

Finally, in the seven teenth chapter, Alois Moosmüller exam ines inter cul tural conflict manage ment in multina tional corpor a tions (MNCs). Cultural diversity is gener ally regarded as a valu able asset for MNCs. Three examples provided by Moosmüller demon strate that although MNCs endeavor to cultiv ate a global mindset, ethno cen tric atti tudes and work habits still domin ate daily commu ni -ca tion in MNCs. Moosmüller indic ates that cultural differ ence remains a chal-lenge for MNCs. To develop the poten tial for innov a tion and improve the effi ciency of company manage ment, MNCs need to incor por ate diversity into their general oper at ing strategies.

Conclusion

The complex ity of conflict manage ment and resol u tion demands further research. This volume attempts to help satisfy this demand by explor ing the theor et ical issue of conflict nego ti ation in differ ent contexts. It approaches conflict from multiple perspect ives; exam ines conflict beha vior in various cultures and situ ations; reviews the extant liter at ure; and offers new direc tions for future research. We hope that the chapters in this volume can enrich the schol arly liter at ure and provide some prac tical sugges tions in the area of inter cul-tural conflict manage ment.

References

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some univer sals in language usage. Cambridge, U K: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, G. M. (2001). Toward transcul tural under stand ing: A harmony theory of Chinese commu nic a tion. In V. H. Milhouse, M. K. Asante & P. O. Nwosu (Eds.), Transcultural real it ies: Interdisciplinary perspect ives on cross- cultural rela tions (pp. 55–70). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chen, G. M. (2009). Chinese harmony theory. In S. Littlejohn & K. Foss (Eds.),

Encyclopedia of commu nic a tion theory (pp. 95–96). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chen, G. M. (2010). The impact of harmony on Chinese conflict manage ment. In G. M. Chen (Ed.), Study on Chinese commu nic a tion beha vi ors (pp. 16–30). Hong Kong, China: China Review Academic Publishers.

Chen, G. M. (2014). Harmony as the found a tion of Chinese commu nic a tion. In M. B. Hinner (Ed.), Chinese culture in a cross- cultural compar ison (pp. 191–209). New York, N Y: Peter Lang.

Chen, G. M. (2015). Theorizing global community as cultural home in the new century.

International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 46, 73–81.

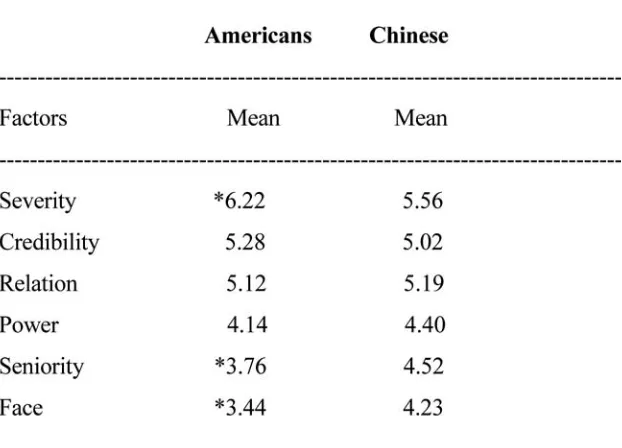

Chen, G. M., Ryan, K. & Chen, C. (2000). The determ in ants of conflict manage ment among Chinese and Americans. Intercultural Communication Studies, 9, 163–175. Chen, G. M., & Starosta, W. J. (2004). Communication among cultural diversit ies: A

dialogue. International and Intercultural Communication Annual, 27, 3–16.

Christians, C. G. (2014). Primordial issues in commu nic a tion ethics. In R. S. Fortner & P. M. Fackler (Eds.), The hand book of global commu nic a tion and media ethics (pp. 1–19). Malden, M A: Wiley-Blackwell.

Goffman, E. (1955). On face- work: An analysis of ritual elements in social inter ac tion.

Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 18(3), 213–231.

Graham, J. (1985). The influ ence of culture on the process of busi ness nego ti ations: An explor at ory study. Journal of International Business Studies, 16(1), 81–96.

Han, B., & Cai, D. A. (2015). A cross- cultural analysis of avoid ance: Behind- the-scene strategies in inter per sonal conflicts. Intercultural Communication Studies, 24(2), 84–122.

Hu, H. C. (1944). The Chinese concept of “face”. American Anthropologist, 46, 45–64. Kozan, M. K. (1989). Cultural influ ences on styles of hand ling inter per sonal conflicts:

Comparisons among Jordanian, Turkish, and U.S. managers. Human Relations, 42(9), 787–799.

10 Xiaodong Dai and Guo-Ming Chen

Marsella, A. J. (2005). Culture and conflict: Understanding, nego ti at ing, and recon cil ing construc tions of reality. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(6), 651–673. Miike, Y. (2010). Culture as text and culture as theory: Asiacentricity and its raison d’être

in inter cul tural commu nic a tion research. In T. K. Nakayama & R. T. Halualani (Eds.), The hand book of crit ical inter cul tural commu nic a tion (pp. 190–215). Oxford, U K: Wiley-Blackwell.

Moran, R. T., Abramson, N. R. & Moran, S. (2014). Managing cultural differ ences. New York, N Y: Routledge.

Oetzel, J., Dhar, S. & Kirschbaum, K. (2007). Intercultural conflict from a multi level perspect ive: Trends, possib il it ies, and future direc tions. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 36(3), 183–204.

Ojelabi, L. A. (2010). Values and the resol u tion of cross- cultural conflicts. Global Change, Peace & Security, 22(1), 53–73.

Siira, K., Rogan, R. G. & Hall, J. A. (2004). “A spoken word is an arrow shot”: A compar ison of Finnish and U.S. conflict manage ment and face main ten ance. Journal of International Communication Research, 33(1/2), 89–107.

Tata, J. (2000). Implicit theor ies of account- giving: Influence of culture and gender.

International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 24(4), 437–454.

Ting-Toomey, S. (1988). Intercultural conflicts: A face- nego ti ation theory. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in inter cul tural commu nic a tion (pp. 213–235). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Ting-Toomey, S. (2005). The matrix of face: An updated face- nego ti ation theory. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about inter cul tural commu nic a tion (pp. 71–92). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ting-Toomey, S., & Oetzel, J. G. (2001). Managing inter cul tural conflict effect ively. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ting-Toomey, S., & Oetzel, J. G. (2003). Cross- cultural face concerns and conflict styles: Current status and future direc tions. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Cross- cultural and inter-cul tural commu nic a tion (pp. 127–147). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Wilmot, W., & Hocker, J. (2007). Interpersonal conflict (7th ed.). Boston, M A: McGraw-Hill.

PART I

Perspectives on the study

of inter cul tural conflict

1

MOVING FROM CONFLICT

TO HARMONY

The role of dialogue in bridging differ ences

Benjamin J. Broome

It is easy to become pess im istic about the possib il ity of living in harmony in our increas ingly diverse world. We hear daily reports in the media about suicide bomb ings, drone strikes, terror ist attacks, violent protests and demon stra tions, gang warfare, organ ized crime, human traf fick ing, and many other forms of vio -lence. Indeed, there is abund ant evid ence of violent conflicts occur ring around the world. In their analysis of armed conflicts from 1946 to 2013, Themnér and Wallensteen (2014) report that since the end of World War II there have been 254 armed conflicts active in 155 loca tions around the world. In 2013 alone, there were 33 armed conflicts occur ring in 25 loca tions world wide. Disturbingly, there were 15 new conflicts in the three years preced ing their analysis. Many of these conflicts are civil wars, lower- level insur gen cies, and other forms of conflict that can tear a country apart for decades, and some times perman ently.1 Although

there are also many posit ive and uplift ing stories of people working together cooper at ively, and despite the study by Pinker (2011) that shows that viol ence is lower today than during previ ous periods of history, the preval ence of war and other forms of viol ence could certainly create a percep tion that the world is hope-lessly embroiled in conflict.

High- tension conflicts are costly. Some of the effects are mater ial: human lives are lost; phys ical prop erty is destroyed; essen tial infra struc ture is damaged; public health systems no longer func tion prop erly; educa tion systems are severely disrup ted; and outside invest ment dries up. All of these can have devast at ing effects on the economy and future devel op ment of a country in conflict (Glaeser, 2009).2 Other costs are less visible and less quan ti fi able but can have consequences

14 Benjamin J. Broome

adoles cence for many chil dren and young people; disrup ted, delayed and often never- completed educa tion; brain drain from the emig ra tion of an educated work force; reduced invest ment and tourism from abroad; and the devast at ing effects of a break down in trust mani fest ing itself both in indi vidu als’ confid ence in society and divi sions between groups that once lived together in harmony. And the effects go far beyond the country in which the war is taking place, affect ing neigh bor ing states and areas far away from the conflict itself, as we are seeing now with the refugee crisis in Europe.3

Given the over whelm ing negat ive consequences of conflict and viol ence, clearly there is a need to promote greater harmony in the face of increas ing confront a tions. Unfortunately, the quest for harmony can seem despair ingly out of reach in a world filled with tensions eman at ing from racial, reli gious and resource- based conflicts. For some, discus sions of peace and harmony might seem to be wishful think ing or even delu sional. Even for those dedic ated to build ing peace, many ques tions arise when discuss ing harmony and conflict: What has brought about the break down in harmony that seems to char ac ter ize today’s world? Can anything be done to coun ter act the disrupt ive forces acting against harmony? Is harmony even possible in the face of so much viol ence and destruc-tion? Is there reason to believe that harmony will be achieved someday? These are all reas on able ques tions, but they are often guided by a view that harmony is a quiet and stable state of exist ence, in which people are in agree ment about issues and every one acts in concert within an estab lished order. Such a view of harmony is an ideal istic aim that is unachiev able and even dysfunc tional in a healthy society.

In this chapter, a concep tion of harmony is adopted that emphas izes differ ence rather than same ness and that focuses on process rather than outcome. Drawing on both ancient Greek and Chinese approaches to harmony, the argu ment will be made that instead of viewing conflicts as a threat to harmony, they should be seen as an essen tial part of the harmon iz a tion process. Indeed, conflicts over seem ingly incom pat ible goals can some times serve as the impetus for indi vidual and social changes that need to be made in order to address the under ly ing causes for the conflicts. And although differ ences, by their very nature, will cause disagree ment and discord, we are not destined to live in a violent world. An altern at ive to vio -l ence is dia-logue, which has the poten tia-l to promote harmony and -lead to greater peace in conflict- torn soci et ies. This chapter will suggest ways in which dialogue can help bring about more peace ful ways of dealing with differ ences, contrib-ut ing to a process of harmony that embraces, rather than avoids, diversity and change.

Harmony: going beyond agree ment and conform ity

rather straight for ward concept that is easy to define. In the English language, the word “harmony” is usually asso ci ated with agree ment, getting along without prob lems, toler at ing differ ences, avoid ing conflicts and exper i en cing consensus across issues of concern to society. Even with posit ive connota tions, the pursuit of harmony is often regarded in the West as naïve or even harmful in the face of strong differ ences. Perhaps because of the indi vidu al istic focus in the West, harmony is considered to be some what of a weak concept. Although it is a posit ive value, it is not one to be placed above stand ing up for one’s rights or defend ing one’s posi tion when there are conflicts. Many influ en tial academic and activ ist figures, includ ing polit ical liber als and staunch defend ers of human it ies educa tion, focus more on justice and human dignity than on finding ways to pursue harmony (see, for example, Nussbaum, 2001). Harmony is often juxta posed with the need to fight for one’s rights. For Westerners, the choice is clear: you must stand up for your beliefs and be willing to fight for what you believe is right fully yours rather than “give in” in the hopes of preserving harmony.

In the East, harmony is treated quite differ ently, partic u larly in places such as Thailand, Japan, Korea and China. In these soci et ies, harmony is viewed as a primary value and it is seen as under ly ing a great deal of human inter ac tion (Chen, 2011). The group- based and hier arch ic ally oriented nature of many Asian soci et ies leads their members to seek harmony by avoid ing outward displays of anger (Hu, Grove & Zhuang, 2010); refrain ing from enga ging in argu ment espe-cially when it involves disagree ment (Hazen & Shi, 2009); showing self- restraint; saving face; avoid ing direct criti cism of others; exhib it ing modesty; and prac -ticing gener os ity (Wei & Li, 2013). Sustained by polite ness and respect, soci et ies with a Confucian tradi tion will usually display a cour teous atti tude toward others in an effort to build a harmo ni ous commu nic a tion climate (Chen, 2014). In general, the emphasis on harmony means that people are more disposed to engage in nego ti ation when differ ences arise, are more willing to comprom ise, and are less inclined to engage in confront a tion when faced with conflict.

In contrast to contem por ary treat ments of harmony in both the West and the East that tend to emphas ize agree ment and simil ar ity, ancient concep tions of harmony gave import ance to tension and dissim il ar ity. The English term harmony is from the ancient Greek word harmo nia, which means the joining or coming together of differ ent entit ies. The ancient Greek philo sopher Heraclitus (6th century BCE ) defined harmony as oppos ites in concert, believ ing that harmony exists when dispar ate forces are held in tension (Graham, 2015).4 Using the

16 Benjamin J. Broome

through seeking agree ment and same ness. Everything is subject to internal tension, and harmony comes from oppos ing elements and move ments pulling in oppos ite direc tions but finding equi lib rium. Harmony is not a matter of prop erly orient ing ourselves to preex ist ing struc tures or condi tions; rather, the struc ture of the world is itself the result of the harmon iz ing process, in which differ ent forces are integ rated into dynamic unity (Li, 2008).

The emphasis on diversity and unity was also reflec ted in the teach ings of the Chinese philo sopher Confucius, who like Heraclitus lived during the 6th century BCE. For Confucius, harmony is a gener at ive and creat ive process in which diverse elements are brought together to form a complex and inclus ive world. To produce good music, musi cians must be able to mix together very differ ent sounds so that they comple ment and complete one another. Likewise, to produce a deli-cious dish, good cooks must be able to mingle ingredi ents with contrast ing flavors and differ ent tastes. With both music and food, differ ent elements complete each other and enhance one another, coming together in a coher ent and harmo ni ous way. However, harmony is much more than simply mixing sounds and ming ling flavors; rather, it requires that the various elements enrich one another by form ing a rela tion ship in which they mutu ally compensate for one another’s short -com ings; mutu ally rein force one another’s strengths; and mutu ally advance each other’s paths toward fulfill ment. Even the five virtues of Confucianism—human excel lence, moral right ness, ritu al ized propri ety, wisdom and sageli ness—need to be prac ticed in harmony in order to achieve happi ness and the prosper ity of the world (Li, 2008).

As with Heraclitus, Confucius stresses the dynamic nature of tension and diversity within harmony. In the Confucian view, conflict between parties, when it is handled prop erly, serves as a step toward harmony. Although the Confucian way advoc ates self- restraint, subdu ing emotions in public and indir ect expres-sions of approval, it is at the same time built around the coex ist ence of differ ence. When facing a contro ver sial issue, the Confucian approach calls for taking into account the whole picture and resolv ing the differ ences through face work, social connec tions and reci pro city (Wei & Li, 2013). For Confucians, harmony is depend ent on a continu ous process of managing oppos ing forces through give and take. Li (2014) uses the example of rocks and water in a river, where both have to yield in some way. Through this “nego ti ation” process, order is estab-lished, although this order is constantly chan ging.

compon ent finds an appro pri ate place and none of the compon ents exclude or suppress one another. Even when elements are in conflict, one or more of them can change posi tions or at least be stabil ized within the system so that they are not disrupt ing it in ways that are damaging to its overall struc ture or its long- term viab il ity.

Although harmony emphas izes balance and equi lib rium, conflict is also part of the harmon iz a tion process. Unlike simple differ ences, where harmony can be achieved when contrast ing elements comple ment one another within a larger pattern, conflict produces a level of tension that can put harmony at risk. This usually neces sit ates a nego ti ation process in which parties need to jointly explore ways to modify their posi tions to accom mod ate the other or find creat ive ways to satisfy both of their needs. By taking an inclus ive approach and using the tension between posi tions to engage in creat ive explor a tion, it is possible to find harmo ni ous solu tions to conflicts.

While there is no panacea, one of the import ant means for encour aging and nurtur ing harmony across differ ence is dialogue, a concept and a prac tice that, like harmony, is frequently misun der stood and that, despite having posit ive asso ci-ations, is not widely seen as a power ful force in the face of conflict. But if we can move beyond a view of harmony as same ness, accord, conform ity and uniform ity, and instead under stand harmony as encom passing diversity and creat ive tension, then we will be posi tioned to under stand how dialogue can help trans form conflict into harmony. The next section will explore the nature of dialogue and will propose several ways in which it can be a key compon ent in harmon iz ing the tension that is inev it able in today’s conflict- filled world.

Dialogue: a path from conflict to harmony5

The ques tion of how to harmon ize protrac ted conflict situ ations is one that has long concerned diplo mats, community leaders, research ers and anyone seeking to bridge the divide between disput ing parties. Certainly, there are no easy answers, and any possib il ity for progress will need to involve multiple levels of society and numer ous approaches for moving forward. But dialogue can be a key piece of the strategy both for prevent ing soci et ies from falling apart under pres sures from seem ingly insur mount able differ ences, and for enga ging in a healing process once soci et ies have succumbed to the ravages of viol ence. By bring ing indi vidu als with a variety of perspect ives together in a safe space, differ ent voices can be heard and creat ive ideas can be gener ated, provid ing oppor tun it ies to learn from others and expand one’s perspect ive on the conflict and the possib il it ies for the future.

18 Benjamin J. Broome

to be manip u lated or changed in some way, and the “I–Thou” rela tion ship, in which people are viewed as having unique histor ies that shape their beliefs, atti tudes and values (Buber, 1958). An I–Thou encounter is char ac ter ized by curi os ity, discov ery and learn ing, while an I–It encounter is centered on persua-sion, posi tion ing and argu ment. In Buber’s view, dialogue is a way of being with others, a way of acknow ledging the complex ity of other people’s exper i ences and of seeking to under stand their perspect ives. Buber’s views reflect the type of harmony that is described in the previ ous section, and commu nic a tion that is char ac ter ized by I–Thou dialogue can play a crit ical role in the harmon iz a tion process that needs to occur in response to conflict.6

One of the concepts intro duced by Buber, the notion of the “between,” has gained trac tion among several schol ars who study dialogue. Buber (1958) uses the “between” as a meta phor for the dialo gic space that exists between persons in a rela tion ship. This common center of discourse brings people together in conver sa tion, allow ing meaning to be co- consti tuted during dialogue. In this way, people create new under stand ings through their inter ac-tion by enga ging in a process that Stewart (1983) labels “inter pret ive listen ing,” Bohm (1996) refers to as “collect ive intel li gence” and Broome (2009) terms “rela tional empathy.” By giving atten tion to the “between,” dialogue points to the inter de pend ence of self and other, the inter sub jectiv ity of meaning, and the emer gent nature of under stand ings (Stewart, 1978, 1983). This type of exchange is perhaps the best way to harness the tension gener ated by conflict and use it as a spring board for trans form ing rela tion ships and gener at ing creat ive ideas, both of which are keys to the process of harmon iz a tion in conflict situ ations.

On a prac tical level, dialogue often takes the form of struc tured group inter-ac tion. Individuals from oppos ing sides of a conflict are brought together in a safe space, usually under the guid ance of a third- party, in which parti cipants can engage in facil it ated discus sions. Although they usually require great care to set up and special expert ise to facil it ate, struc tured dialogue groups can provide a setting for examin ing the basis for a conflict, repair ing damaged rela tion ships, and explor ing steps that might be taken to address crit ical issues that are embed ded in the conflict. Structured dialogue groups can take a variety of forms, from small informal meet ings to insti tu tion al ized discus sion groups that meet on an ongoing basis over a long period of time.7

But the essence of any form of dialogue is to enable an exchange of views, perspect ives and ideas that is centered on foster ing mutual respect and under stand ing and creat ing mutu ally embraced path ways for joint action.

rela tions in inter na tional conflicts. These sessions are primar ily oriented toward helping parti cipants learn about each other, devel op ing better commu nic a tion across the divide, and estab lish ing working rela tion ships (Doob, 1981; Volkan, 1998; Wedge, 1967). In the psycho dy namic approach, an attempt is made to human ize the “enemy,” build confid ence, and over come hatred, all of which helps uncover emotional issues that might other wise affect the conflict t ively. Between the rational and psycho dy namic approaches are those that focus on both rela tion ship and substance (Azar, 1990; Fisher, 1997; Kelman, 1982). Typically, these approaches give equal emphasis to both the educa tional and the polit ical aspects of the conflict; they attempt to produce changes in the atti tudes and percep tions of the parti cipants while simul tan eously trans fer ring these changes to a broader soci etal discus sion or to the polit ical arena.

Of course, in situ ations with a long history of divi sion, making progress requires a system atic, prolonged set of dialogues commit ted to the trans form a tion of conflic tual rela tion ships. Decades, or even centur ies, of enmity cannot be over come overnight, and there are many forces in the society and larger context of the conflict that can quickly undo any progress from dialogue sessions. Lederach (1997) suggests that dialogue must give emphasis to both peace and justice, as well as to both truth and mercy, in order to be effect ive. The goal of dialogue is the long- term trans form a tion of a “war system” into a “peace system” that is char ac ter ized by polit ical and economic parti cip a tion, peace ful rela tion-ships and social harmony (Lederach, 1999, 2003). The aim is to create an infra-struc ture for peace that simul tan eously addresses—and involves—all the differ ent levels of a society that have been affected by conflict: from the grass roots level (the vast major ity) to national leaders (e.g. ethnic/reli gious leaders, leaders of non- govern mental organ iz a tions, academ ics/intel lec tu als) and the top level of polit ical and milit ary lead er ship (Lederach, 1997).

20 Benjamin J. Broome

Identifying differ ences

Conflict occurs at least in part because of differ ences in perspect ives, goals and the means to achieve desired outcomes. Often in conflict situ ations, groups on each side will operate accord ing to stereo types and miscon cep tions that can keep them apart and lead them to take unne ces sary actions against each other. It is import ant to identify and acknow ledge these differ ences so they can be appro pri-ately addressed by the conflict ing parties. Unfortunpri-ately, conflict can further rein force and promote bias and preju dice by prevent ing the type of contact that can break down miscon cep tions and help each party better under stand the other. Over time, this tends to become insti tu tion al ized, which further solid i fies the bound ar ies between the parties in the conflict (Hewstone & Greenland, 2000).

Structured dialogue provides an import ant avenue for helping groups under-stand each other’s views of the conflict; learn about each other’s aspir a tions for the future; and identify the issues on which they hold contrast ing opin ions. Of course, simply bring ing people together will not by itself lead to the construct ive iden ti fic a tion of differ ences. The contact hypo thesis that Allport (1954) origin-ally described in his book The Nature of Prejudice, which was exten ded by Amir (1969), Cook (1978), Hewstone and Greenland (2000) and Pettigrew (2008), among others, demon strates that inter group contact is effect ive primar ily under condi tions of equal status, sustained inter ac tion, cooper at ive inter de pend ence and social norms of equal ity. These condi tions can be cultiv ated through dialogue, allow ing groups to effect ively identify the differ ences that divide them. Only when this happens can groups start the process of finding ways to build harmony based on these differ ences.

Harnessing and trans form ing tension

The differ ences that exist within any society are always a poten tial source of destruct ive tension. In a harmo ni ous world, tension is the basis for a strong society, as it is for the bow and lyre that Heraclitus described in his writ ings. And it is the basis for a pros per ous society, where a mix of perspect ives, prac tices and dreams allows a society to flour ish with creat ive and innov at ive ideas. But the tension that arises from violent conflict has a destruct ive effect, driving people apart and suppress ing imagin a tion and origin al ity. Anxiety and fear domin ate, and people put up defens ive walls to protect them selves. These walls constrain inter ac tion; stem the free flow of ideas; and thwart the possib il ity for collab or-at ive inquiry. Instead of diversity leading to a bold and excit ing future, differ-ences set society on a regress ive path of short- sighted policy decisions and repress ive meas ures.

in conver sa tion that explores the basis for differ ences that exist between compet ing groups, can help tilt the flow of negat ive energy toward posit ive ends. As Salomon (2009) suggests, it is crit ical to cultiv ate more posit ive atti tudes toward the other side and more posit ive atti tudes toward peace. Bar-Tal (2009) agrees when he advoc ates devel op ing “an emotional orient a tion of hope that reflects the desire for the posit ive goal of main tain ing peace ful and cooper at ive rela tions with the other party” (p. 369). Dialogue can aid in creat ing a “posit ive vision based on human-istic and inclus ive ideals without an inher ent destruct ive poten tial . . . [with a] focus on the possib il ity of, and satis fac tions inher ent in connec tion to, community and peace” (Staub, 1996, p. 147).

Restoring balance and equi lib rium

Many of the conflicts described in the intro duct ory section are part of systems that have been char ac ter ized by dishar mony for an exten ded period of time. They have become what Coleman (2003) terms “intract able conflicts,” often involving ethnic victim iz a tion, unad dressed histor ical griev ances and traumas, economic asym met ries, unequal distri bu tion of resources and struc tural inequal it ies. Resulting in assault, torture, murder and other heinous crimes, the outcome is an imbal ance that shifts society further away from the possib il ity of harmo ni ous rela tions. The griev ances that resid ents of conflict zones accu mu late leave deep scars of anger and a sense of victim hood and a will for revenge (Bar-Tal, 2009). Bringing society back to a state of equi lib rium is not an easy task when there is a culture of conflict, mistrust and suspi cion, as well as a flour ish ing of “enemy images.” The atro cit ies commit ted by parties against each other create a tend ency for indi vidu als in violent conflicts to demon ize those on the other side, causing them to attrib ute the causes of their suffer ing and exper i ences of injustice exclus-ively to the other.

22 Benjamin J. Broome

import ant build ing block that brings into balance the forces that were pushing people apart.

Nurturing inclus ive ness

One of the most destruct ive aspects of violent conflict is the inev it able form a tion of ethnic and sectarian factions (Montville, 1990). Humans have a deep- rooted psycho lo gical tend ency, at both the indi vidual and group levels, to dicho tom ize by creat ing “enemies” and “allies.” Unconscious impulses often result in former neigh bors harming and killing each other simply because they belong to differ ent national or ethnic groups (Mack, 1990). As events unfold, each side adopts a partisan, skewed and unilat eral declar a tion of griev ances and becomes fiercely preoc cu pied with assert ing its rights, making it blind to the need for attend ing to and mending intereth nic rela tions. Giving so much atten tion to one’s own griev-ances and rights simply deepens the estrange ment of the communit ies in conflict, and there is little concrete engage ment between the two sides.

Dialogue allows indi vidu als from conflict ing groups to turn toward each other and gain an aware ness of their inter con nec ted ness, common human ity and shared interests. Through the exper i ence of sitting in the same room with one another, parti cipants can come to under stand each other’s culture and every day concerns, and learn about their history and personal exper i ences. By exchan ging personal stories and enga ging in mutual analysis of the conflict and its effects, the other can be legit im ized and human ized. Kriesberg (2004) suggests that a regard for the other takes hold in dialogue groups, allow ing for the possib il ity of differ ent ways of life exist ing side- by-side. By listen ing to what the other has to say, and allow ing for its authen ti city, respect can slowly emerge. Mutual recog ni tion of each other’s human ity and legit im acy enables accom mod a tion and may even-tu ally allow parti cipants to come to see their adversar ies as worthy of respect. Such respect, and the corres pond ing trust that often accom pan ies it, devel ops gradu ally as parti cipants slowly and care fully reveal their own hurt and pain, and find a posit ive recep tion from the other. With suffi cient dialogue, rivals can become legit im ate part ners in peace (Bar-Tal, 2009). Conflict can slowly move from the dishar mony of exclus ive ness to the harmo ni ous rela tions made possible by inclus ive ness.

Promoting cooper a tion