Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:02

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

The Effect of a Business and Society Course on

Business Student Attitudes Toward Corporate

Social Responsibility

Denise Kleinrichert , Jennifer Tosti-Kharas , Michael Albert & Jamie P. Eng

To cite this article: Denise Kleinrichert , Jennifer Tosti-Kharas , Michael Albert & Jamie P. Eng (2013) The Effect of a Business and Society Course on Business Student Attitudes Toward Corporate Social Responsibility, Journal of Education for Business, 88:4, 230-237, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.688776

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.688776

Published online: 20 Apr 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 220

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.688776

The Effect of a Business and Society Course

on Business Student Attitudes Toward Corporate

Social Responsibility

Denise Kleinrichert, Jennifer Tosti-Kharas, Michael Albert, and Jamie P. Eng

San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California, USA

The authors investigated the impact of an undergraduate business and society course on stu-dents’ attitudes about the importance of corporate social responsibility (CSR) at a highly diverse, urban, Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business–accredited U.S. uni-versity. Students were surveyed for their attitudes about key areas of business and CSR. Findings indicated that students who had completed the course were less likely to believe that a company’s primary responsibility was to maximize shareholder value, and were more likely to believe that creating value for the local community was a company’s primary responsibility. However, the authors found there were no significant differences for some other CSR attitudes investigated.

Keywords: business and society course, corporate social responsibility, stakeholder impacts,

student attitudes, undergraduate business curriculum

Business schools have been subjected to media criticism of their graduates’ lack of socially responsible attitudes in making business decisions. These recent criticisms focus on the predominant curriculum focus of many business schools, which continues to be one where profit outcomes and share-holder value are stressed as more important than are consid-erations of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as an ethical practice of business decision making. CSR is a commitment by business to use its profits and talents to enhance the social, ethical, and environmental wants and needs, or quality of life, of stakeholders (McGlone, Spain, & McGlone, 2011). Over the past two decades, many, but not all, U.S. business schools have modified their undergraduate curriculum with an upper division core business and society course focusing on ethi-cal values and CSR. These courses are designed to provide students with an understanding of the role of business in so-ciety and the importance of making business decisions with an ethical lens toward CSR. Moreover, society has expecta-tions of the ethical attitudes of business graduates because “society now demands responsible behavior from

corpora-Correspondence should be addressed to Denise Kleinrichert, San Francisco State University, College of Business, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94132, USA. E-mail: DK@sfsu.edu

tions and links related behaviors to a corporation’s iden-tity” (Nicholson & DeMoss, 2009, p. 217). During this time, the American Association of Collegiate Business Schools (AACSB) developed assurance of learning standards that business schools must demonstrate as part of their accredita-tion process. For example, AACSB accreditaaccredita-tion guidelines in 2010 stated that business curriculum must include compo-nents of, “global, environmental, political, economic, legal, and regulatory context for business,” such as may be found in a business and society course (p. 71; Lawrence, Reed, & Locander, 2011; Kennedy & Horne, 2007; Nguyen, Basuray, Smith, Kopka, & McCulloh, 2008).

Despite the importance placed on adding CSR subject material to business curricula, there is a gap in the study of whether these courses actually affect undergraduate stu-dents’ attitudes of CSR as an expected role of business in society. The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of a business and society course on student attitudes about CSR to (a) understand the student attitudes of CSR char-acteristics of business practice using a survey instrument, and (b) compare our findings with other empirical studies of undergraduate business students. We investigated a highly di-verse demographic student population studying toward a four year, bachelor of science of business administration (BSBA) degree at a large urban state university.

EFFECT OF A BUSINESS AND SOCIETY COURSE ON STUDENT CSR ATTITUDES 231

CSR THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS AND STUDENT STUDIES

One fundamental debate in academic literature is the meaning of CSR for business practice (American Society for Quality, 2006; Andriof & Waddock, 2002; Aupperle, Carroll, & Hatfield, 1985; Basu & Palazzo, 2008; Brummer, 1983; Carroll, 1979, 1991; Devinney, 2009; Freeman & Liedtka, 1991; Harrison & Freeman, 1999; Windsor, 2002). CSR, broadly construed, includes the concepts, ideals, attitudes, and practices of companies that demonstrate ethical concern with the well-being of their stakeholders and society. Some academics have expanded the notion of CSR to specifically include corporate ethics in the acronym CESR (Simmons, Shafer, & Snell, 2009). In addition, market trends emphasize CSR outlooks and practices in business (Nicholson & DeMoss, 2009). Moreover, Gopalakrishnan, Mangaliso, and Butterfield (2008) stated that corporate “citizenship behavior is not simply an individual act but a social process” (p. 758). In other words, the approaches businesses choose to engage toward CSR are “an integrated process that simultaneously incorporates concerns for bottom-line profitability (doing things right) and societal concerns (doing the right things)” (Gopalakrishnan et al., 2008, p. 758). The academic literature and mainstream business news reporting offer criticism toward business school education and its negative impact on the mindsets of society’s future business leaders (Ghoshal, 2005; Giacalone & Thompson, 2006; Holland, 2009; Middleton, 2010; Middleton & Light, 2011; Mitroff, 2004; Pfeffer, 2005; Wynd & Mager, 1989). Therefore, it has been argued that business students need a strong CSR-pervasive course—for example, a course on business and society—to better prepare graduates for socially-minded contemporary business practices (AACSB, 2010).

The idea of corporate responsibility, or the theory that business is accountable for its decision-making impacts on its market (e.g., consumers, employees and suppliers) and nonmarket (e.g., communities and the environment) stakeholders, emphasizes a stakeholder consideration in business decision making. This view does not solely empha-size shareholder value as business’ only responsibility. The stakeholder theory (Freeman & Liedtka, 1991) holds that corporations are responsible as corporate citizens to ethical obligations to the communities in which they operate or impact (Carroll, 1991; Easterly & Miesing, 2009; Meehan et al., 2006; Waddock, 2004). The gap between business practices and society’s stakeholder impacts is bridged by the corporate citizenship theory, which grants corporations the role of community citizen by virtue of doing business and impacting its stakeholders as a member of society. In other words, business’ attitudes about their role in society must include their responsibility for decision-making and actions that affect other members of that society (Birch, 2003; Drucker, 1946; Easterly & Miesing, 2009).

A number of studies of undergraduate students (Glenn, 1992; Holland, 2009; Kolb & Kolb, 2005; Kraft, 1991; Kraft & Singhapakdi, 1991, 1995; Luthar and Karri, 2005; Moberg & Seabright, 2000; Ng, White, Lee, & Moneta, 2009; Nguyen, 2008; Simmons, Shafer, & Snell, 2009; Stead & Miller, 1988; Wilhelm, 2008) demonstrate the significant impact of a specific business and society-type course on student attitudes about a company’s stakeholder responsi-bilities. Further, Arlow’s (1991) business student respon-dents were significantly more favorable toward the notion of CSR than surveyed nonbusiness students. McGlone et al. (2011) had significant findings regarding student exposure to “companies’ efforts at incorporating social responsibil-ity [which] significantly affected the students’ opinions” (p. 200) subsequent to CSR-related educational events. Further, Nguyen et al. demonstrated “the linkage between students’ learning in ethics and their subsequent ethical intention” (p. 73). Neubaum, Pagell, Drexler, McKee-Ryan, and Larson’s (2009) study demonstrated that “businesses should be judged on social and environmental performance” (p. 17; Friedman, 1970) and students ranked these factors as more important than traditional, Friedmanesque bottom-line profit perspec-tives. Moreover, Simmons et al., Neubaum et al., and Glenn demonstrated significant findings that a business and soci-ety course directly impacts student attitudes about ethical business practices.

Some have argued that business and society courses do not result in measurable positive impacts on student atti-tudes about CSR (Vogel, 1991a, b). Felton and Sims (2005) argued that “making ethical decisions is not a simple pro-cess” because “ethics is embedded in all business decision-making” (p. 381). According to this perspective, a single, stand-alone ethics course is not sufficient to impact the ethical or CSR attitudes of undergraduate students. Moreover, others have argued that CSR theory is both vague and ambiguous (Shaffer, 1977, 1978). Other authors argued that ethical at-titudes cannot be taught, but are formulated early in life or are due to an innate strong moral identity (Budner, 1987; Davis & Welton, 1991; O’Fallon & Butterfield, 2011; Wynd & Mager, 1989). The controversy in the literature regarding the impact of a standalone business and society course on student attitudes about CSR is unresolved. Therefore, our investigation seeks to determine the significance of the im-pact of a business and society course on CSR attitudes of undergraduate business students.

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

Increasingly, undergraduate business students across the United States are from diverse demographic backgrounds, are working in a variety of business enterprises, and bring a variety of life experiences into classrooms. Therefore, our study samples a diverse student population at an urban university with over 75% of undergraduate business students

having some work experience and 15–20% or these students holding supervisory or managerial roles. At this university, all business seniors take a culminating series of courses in their major area of study and a single required capstone business and society course focused on CSR. The business and society course emphasizes the interaction of business with political, legal, social, ethical, and natural environments in society. All students in this university’s BSBA program are exposed to theoretical perspectives and business applications of ethics, business challenges, managerial decision making, the Stakeholder Model, and CSR practices by business. This survey asked students to state their attitudes about the im-plication of a number of company responsibilities to various stakeholders—economic (profit–shareholder value impacts), social (human impacts), and natural environment (air, land, water, species, climate impacts) using questions from the Aspen Institute Center for Business Education (2008) survey.

Hypotheses

We felt several elements of the business and society course would contribute to impacting students’ attitudes about CSR. First, since the course was a capstone course coming at the end of students’ undergraduate business studies, we felt that they would have the necessary background to understand the complex arguments for social and ethical responsibility in business that were presented in the course. Second, we expected student attitudes to be influenced by the business and society course such that students who had completed the course would place more importance on CSR in business than students who had not completed the course.

To test our hypotheses, we examined the differences be-tween those students who had not taken the business and society course and those who had completed it. Our first four hypotheses specifically examined four attitudinal aspects at-tributed to CSR practices of well-run companies: corporate values and strong codes of ethics, focusing on employee issues, creating community value, and enhancing environ-mental conditions in the community.

Hypothesis 1(H1): There would be a significant difference between the CSR attitudes of seniors prior to taking a business and society course and seniors after taking the business and society course, such that those who have taken the course would be more likely to believe that a well-run company operates according to its values and strong code of ethics.

H2: There would be a significant difference between the CSR

attitudes of seniors prior to taking a business and society course and seniors after taking the business and society course, such that those who have taken the course would be more likely to believe that a well-run company places a focus on employee issues.

H3: There would be a significant difference between the CSR

attitudes of seniors prior to taking a business and society

course and seniors after taking the business and society course, such that those who have taken the course would be more likely to believe that a well-run company creates products or services that benefit society.

H4: There would be a significant difference between the

CSR attitudes of seniors prior to taking a business and society course and seniors after taking the business and society course, such that those who have taken the course would be more likely to believe that a well-run company adheres to progressive environmental policies.

Further, we investigated student attitudes about the pri-mary responsibility of a company, which include practices related to both shareholder and stakeholder value theories of a company’s operations, using an additional three hypotheses.

H5: There would be a significant difference in CSR attitudes

between seniors prior to taking a business and society course and seniors after taking the business and society course, such that those who have taken the course would be less likely to view maximizing shareholder value as a company’s primary responsibility.

H6: There would be a significant difference in CSR attitudes

between seniors prior to taking a business and society course and seniors after taking the business and soci-ety course, such that those who have taken the course would be more likely to view creating value for the local community as a company’s primary responsibility.

H7: There will be a significant difference in CSR attitudes

of seniors prior to taking a business and society course and seniors after taking the business and society course, such that those who have taken the course will be more likely to view enhancing environmental conditions as a company’s primary responsibility.

METHODS

We used a survey of two distinct undergraduate student populations—seniors prior to taking a business and society course (pre-B&S seniors), and seniors after taking a busi-ness and society course (post-B&S seniors) to test the seven hypotheses.

Participants

A total of 356 business seniors who took the business and society course in the fall academic semester participated in this study. Pre-B&S seniors (n=206) completed the survey on the first class meeting prior to any course content in-struction. Post-B&S seniors (n=150) completed the survey in the last week of course instruction. The surveyed stu-dents had various intended major areas of study concentra-tion (i.e., marketing, finance, management, accounting, deci-sion sciences, information systems, international business), which eliminated student self-selection bias (James, 2006). We used separate class sections of about 30 students each to

EFFECT OF A BUSINESS AND SOCIETY COURSE ON STUDENT CSR ATTITUDES 233

TABLE 1

Demographics: Ethnic Origins

Ethnic Pre-B&S Post-B&S

origin seniors (%) seniors (%)

African American 4 3

Asian American 44 47

Caucasian 20 19

Hispanic American 8 9

Native American 0.05 0

Other 9 11

International/non-U.S. citizen 15 11

independently survey the pre-B&S and post-B&S course en-rollees in this investigation to mitigate students giving so-cially desirable responses. Further, we also varied the two samples across professors and course schedules to avoid bi-ases due to teaching method. We also paired the pre-B&S and post-B&S samples based on time of class day to mitigate student differentials for selecting day versus evening class.

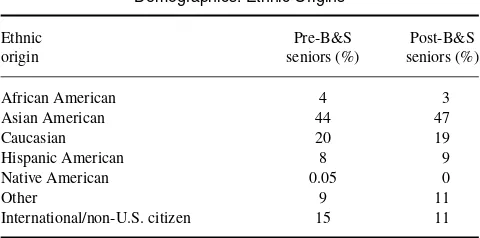

The pre-B&S and post-B&S students had comparable demographics. The ethnic origins of the pre-B&S and post-B&S samples, respectively, were 44% and 47% Asian American, 20% and 19% Caucasian, 8% and 9% Hispanic American, 4% and 3% African American, and 9% and 11% other ethnicities. Fifteen percent of pre-B&S students and 11% of post-B&S students were non-U.S. citizens. Both groups were 50% women and had an average age of almost 25 years (pre-B&S: M = 24.54 years, SD = 3.97 years; post-B&S: M = 24.79 years, SD= 3.79 years). The two groups also had comparable amounts of work experience (for pre-B&S, 75% reported moderate to a lot of work experience compared with 77% post-B&S) and supervisory experience (for pre-B&S, 15% reported moderate to a lot of work experience compared with 20% post-B&S). None of the demographics differences reported between the two groups were significant. Demographic statistics for the two groups are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

TABLE 2 Demographics: Other

Pre-B&S seniors Post-B&S seniors

Demographic % M SD % M SD

Female/male 50/50 50/50

Age (years) 24.54 3.97 24.79 3.79 Work

experience (moderate to a lot)

75 77

Supervisory management experience

15 20

Note.For work experience, remainder was “little to no work experience.”

Survey Instrument

Our survey is a single-point completion, hardcopy research instrument using questions from the Aspen Institute’s MBA Student Attitudes About Business and Society Survey (2008). The Aspen instrument is valuable for testing the CSR atti-tudes of undergraduate students, particularly in light of the changing demographics and increasing work histories of U.S. undergraduate students in business schools (see Tables 1 and 2). For this investigation, students rated 12 items in terms of how important they believed each item was to their definition of a well-run company. Sample items included “operates ac-cording to its values and a strong code of ethics,” “provides competitive compensation,” and “offers high financial return to shareholders.” Each question was close-ended and rated using a 3-point Likert-type response scale whose options ranged from 1 (not important at all) to 3 (very important). In addition, students were presented with 10 items contain-ing potential responsibilities of a company and were asked to circle the one item they believed was the most important. Sample items included “maximize value to shareholders,” “enhance environmental conditions,” and “create value for the local community in which it operates.” The survey took 10–15 min to complete. The students immediately returned the survey to the principal researcher upon completion in the respective classrooms.

The survey and its administration followed strict institu-tional research board guidelines: Participants were provided an implied consent to participate statement, a statement of the confidential format of the survey, and they were requested not to state any personal identifiers on the survey forms or in any of the survey question responses. The survey questions did not solicit sensitive information. There was no risk and no loss of privacy to the student participants. They were also told that the purpose of the research was for statistical analy-sis and research publication only. The students were invited to participate after being told the purpose of the research, but could have chosen not to complete the survey by returning the blank survey to the principal researcher, with no penalty. There were no academic risks to students in participating in this survey, nor were the students offered any incentives to participate.

Blank surveys were not available for use or reference by any students, researchers, or any faculty prior to survey ad-ministration, nor did any faculty or instructors have access to their respective students’ responses at the time of or after sur-vey administration. The 356 collected sursur-vey responses were then entered by three graduate students into Excel spread-sheets by course number and timing (August or December survey dissemination) using precoded question indicators lo-cated on the survey form with cross-auditing for rates of data-entry error. The accuracy of the manual data entry was calculated by sampling 5% of the total surveys and checked for accuracy. This analysis found an error rate of .002, or fewer than two errors per one thousand data fields. Then, the

two student populations were disaggregated into two Excel files for testing. Here we summarize the findings related to the seven hypotheses.

RESULTS

Student Attitudes of Well-Run Companies

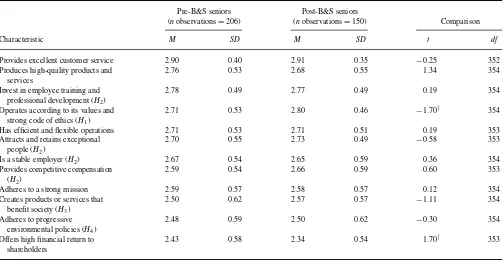

H1 predicted that post-B&S seniors would believe operat-ing accordoperat-ing to values and a strong code of ethics was more important to a well-run company than pre-B&S niors. This hypothesis was supported. That is, post-B&S se-niors rated this item higher (M =2.80, SD =0.46) than pre-B&S seniors (M = 2.71, SD = 0.53), and the dif-ference was significant at p < .10, but not at p < .05,

t(354)= −1.70.

H2 predicted that post-B&S seniors would believe that focusing on employee issues was more important to a well-run company than pre-B&S seniors. This hypothesis was not supported. There were no significant differences be-tween the two groups for the following items: investing in employee training and professional development (pre-B&S: M =2.78,SD=0.49; post-B&S:M =2.77,SD= 0.49),t(354)=0.19,ns; being a stable employer (pre-B&S:

M =2.67,SD=0.54; post-B&S: M =2.65,SD =0.59),

t(354)=0.36,ns; attracting and retaining exceptional peo-ple (pre-B&S:M=2.70,SD=0.55; post-B&S:M=2.73,

SD=0.49),t(353)=0.36,ns); and providing competitive compensation (pre-B&S:M=2.59,SD=0.54; post-B&S:

M=2.66,SD=0.59),t(353)=0.60,ns.

H3 predicted that post-B&S seniors would believe that creating products or services to benefit society was more important to a well-run company than pre-B&S seniors. However, although pre-B&S seniors rated this item lower (M = 2.50, SD = 0.62) than post-B&S seniors (M = 2.57, SD = 0.57), the difference was not significant, t(354) = −1.11, ns. Thus H3 was not supported.

H4 predicted that post-B&S seniors would believe that adhering to progressive environmental policies was more im-portant to a well-run company than pre-B&S seniors. Again, though pre-B&S seniors rated this item lower (M =2.48,

SD=0.59) than post-B&S seniorsM=2.50,SD=0.62), this difference was not significant,t(354)= −0.30,ns. Therefore,

H4 was not supported. However, notably, post-B&S seniors reported that offering high financial return to shareholders was less important to a well-run company (M=2.34,SD= 0.54) than pre-B&S seniors (M=2.43,SD=0.58), and this difference was significant atp<.10,t(353)=1.70,p<.10.

The results of the tests of Hypotheses 1–4 are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3 Test of Hypotheses 1–4

Pre-B&S seniors (nobservations=206)

Post-B&S seniors

(nobservations=150) Comparison

Characteristic M SD M SD t df

Provides excellent customer service 2.90 0.40 2.91 0.35 −0.25 352 Produces high-quality products and

services

2.76 0.53 2.68 0.55 1.34 354

Invest in employee training and professional development (H2)

2.78 0.49 2.77 0.49 0.19 354

Operates according to its values and strong code of ethics (H1)

2.71 0.53 2.80 0.46 −1.70† 354

Has efficient and flexible operations 2.71 0.53 2.71 0.51 0.19 353 Attracts and retains exceptional

people (H2)

2.70 0.55 2.73 0.49 −0.58 353

Is a stable employer (H2) 2.67 0.54 2.65 0.59 0.36 354 Provides competitive compensation

(H2)

2.59 0.54 2.66 0.59 0.60 353

Adheres to a strong mission 2.59 0.57 2.58 0.57 0.12 354 Creates products or services that

benefit society (H3)

2.50 0.62 2.57 0.57 −1.11 354

Adheres to progressive environmental policies (H4)

2.48 0.59 2.50 0.62 −0.30 354

Offers high financial return to shareholders

2.43 0.58 2.34 0.54 1.70† 353

Note.Responses to the question “In your definition of a “well-run” company, how important are the following?” were rated on a 3-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 3 (very important).

†p<.10.

EFFECT OF A BUSINESS AND SOCIETY COURSE ON STUDENT CSR ATTITUDES 235

Primary Responsibilities of a Company

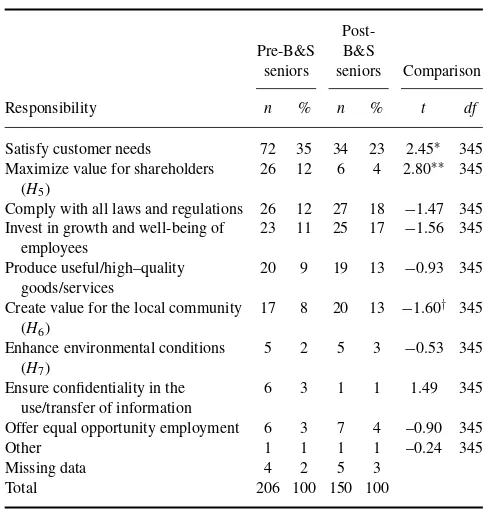

H5 predicted that post-B&S seniors would be less likely than pre-B&S seniors to believe that maximizing shareholder value is the primary responsibility of a company. This hy-pothesis was supported, with 12% of pre-B&S seniors com-pared to 4% of post-B&S seniors indicating that maximizing shareholder value was a company’s primary responsibility,

t(345) =2.80, p < .001. In fact, maximizing shareholder

value was the second most highly rated item for pre-B&S seniors, while it was the seventh most highly rated item for post-B&S seniors.

H6predicted that post-B&S seniors would be more likely than pre-B&S seniors to believe that creating value for the local community is the primary responsibility of a company. This hypothesis was supported, with 8% of pre-B&S seniors compared to 13% of post-B&S seniors indicating that creat-ing value for the local community was a company’s primary responsibility atp<.10,t(345)= −1.60,p<.10.

H7predicted that post-B&S seniors would be more likely than pre-B&S seniors to believe that enhancing environmen-tal conditions is the primary responsibility of a company. Although 2% of pre-B&S seniors indicated that enhancing environmental conditions was a company’s primary respon-sibility, compared to 3% of post-B&S seniors, this differ-ence was not significant, t(345) = –0.53, ns. There was one additional significant difference between pre-B&S and post-B&S seniors regarding the primary responsibility of a company. Thirty-five percent of pre-B&S seniors believed that satisfying customer needs was a company’s primary responsibility, compared with 23% of post-B&S seniors,

t(345)=2.45,p<.05. The results of the tests of Hypotheses

5–7 are presented in Table 4.

DISCUSSION AND LIMITATIONS

The goal of this investigation was to study the influence of the business and society course on undergraduate business student attitudes about the importance of CSR. Our results indicate that the business and society course has a signifi-cant impact on student attitudes about some areas of CSR responsibilities of companies. Seniors who had completed a business and society course were more likely than those who had not completed the course to believe that a well-run com-pany operates according to a strong code of ethics and values. Students who had completed the course were also less likely to believe that a company’s primary responsibility was to maximize shareholder value, and were more likely to believe that creating value for the local community was a company’s primary responsibility. However, there were no significant differences for the other CSR attitudes we investigated, in-cluding employee issues, creating products and services to benefit society, adhering to progressive environmental poli-cies, and enhancing environmental conditions.

TABLE 4

Satisfy customer needs 72 35 34 23 2.45∗ 345 Maximize value for shareholders

(H5)

26 12 6 4 2.80∗∗ 345

Comply with all laws and regulations 26 12 27 18 −1.47 345 Invest in growth and well-being of

employees

23 11 25 17 −1.56 345 Produce useful/high–quality

goods/services

20 9 19 13 −0.93 345 Create value for the local community

(H6)

Offer equal opportunity employment 6 3 7 4 –0.90 345

Other 1 1 1 1 –0.24 345

Missing data 4 2 5 3

Total 206 100 150 100

Note.Responses were to the question, “What do you believe is the primary responsibility of a company?”

†p<.10.∗p<.05.∗∗p<.01.

Given the mixed results of this study, the impact of this course needs further investigation for analyzing business ed-ucation. The required business and society course includes specific theoretical CSR and ethical business applications used in the course at this university. Our findings are con-sistent with prior findings that exposure to CSR theoretical and practice-oriented characteristics of business practice in a specific business and society course has some impact on CSR attitudes of students. It is our contention that a single course may not account for the significant findings in this study, but that a CSR-integrated curriculum inclusive of a business and society course has an important influence on their attitudes (Goodstein & Wicks, 2007). Past literature demonstrates that the investigation regarding stand-alone ethics courses has in-conclusive findings. However, future researchers may be able to explain an integration of ethics across a business curricu-lum, with results that point to why past studies on single point ethics courses have conflicting findings. Therefore, student attitudes about CSR are impacted in some respects during their business school curriculum after taking a business and society course, but further research is needed to further clar-ify these specific attitudes.

Moreover, the students at this university have been ex-posed to multiple ethics and CSR-integrated elements in-side and outin-side of their BSBA curriculum at this univer-sity. These events include an annual business ethics week each November inclusive of corporate ethics and CSR guest

speakers and panelists engaging with students in and outside of classrooms. Faculty also use specific, targeted CSR and ethics discussions of social and environmental impacts of business, case analyses and films throughout the week.

The limitations of our study include methodological and sample aspects. First, a cross-sectional design was used, rather than a longitudinal approach, so we cannot determine the impact of the business and society course on each individ-ual student pre– and post–business and society coursework. Specific student attitudes were not traced for the two survey samples; therefore, student experiences and the correspond-ing impacts on individual students’ attitudes cannot be de-termined. Second, post–business and society course seniors have not necessarily had the same preparatory coursework because they may choose different courses as they progress through their business curriculum. At this university, students choose a study concentration in management, finance, ac-counting, decision sciences, marketing, information systems, or international business. In this regard, students experience a different quantitative and qualitative course progression prior to completing the survey. The faculty in the various concentrations may or may not include the social impacts of business in their course discussions and materials. This may have had an impact on student CSR attitudes (Greenberg, Clair, & Maclean, 2007; Rahdert, 1972). Third, we did not analyze potential impacts of the differences between two dif-ferent course texts used or pedagogical approaches. Fourth, we did not test specific moderating variables in an urban, highly diverse population attending a public university with a variety of socioeconomic, ethnic, racial, gender, and age differences. In addition, students’ level of work history and supervisory or managerial experience is not investigated in this study for specific impact on CSR attitudes (Valentine & Bateman, 2011). A final limitation pertains to the student population level, which only targeted undergraduate business students.

Implications for Further Research

In light of the limitations discussed previously, several follow-up studies are necessary. One study would incorpo-rate a longitudinal examination to determine whether further significant differences occur in the specific attitudes of each student. A second study would examine potential moderat-ing variables regardmoderat-ing impacts on CSR attitudes, includmoderat-ing analysis of any differentiation due to quantitative major (ac-counting, finance, decision sciences, information systems) or a qualitative major (management, marketing, international business). An additional moderating variables study would focus on the specific implications of gender, age, ethnicity or race on student attitudes about CSR. A further moder-ating factor is the potential impact of work history on stu-dents’ CSR attitudes. Our study was done in one large, ur-ban public university in a major U.S. city. Other studies of undergraduates in a variety of other locations of the

coun-try are needed to increase generalizability (Lloyd, Kern, & Thompson, 2005; Traiser & Eighmy, 2011). Finally, the con-tinuing debate about the role of business education as it re-lates to student attitudes about CSR indicates that further investigation of the comparisons of undergraduate attitudes about CSR to MBA attitudes needs revisiting.

Our findings are the result of an inquiry into the under-graduate student attitudes of Millennials (essentially those students born between 1980 and 2000) who are close to graduation. A critical understanding of specific business cur-riculum impacts, such as a business and society course, on CSR attitudes of business students today poses “a monumen-tal challenge to educators to rethink the basic assumptions and the theories by which future corporate leadership is pre-pared for their roles” (du Plessis, 2008, p. 800) in business and society. The future implications of an ethics-integrated curriculum-based CSR analysis would be a complex investi-gation, but would be more valuable than repeated single-point ethics-type course studies.

REFERENCES

Agle, B., Donaldson, T., Freeman, R. E., Jensen, M., Mitchell, R., & Wood, D. (2008). Dialogue: Toward superior stakeholder theory.Business Ethics Quarterly,18, 153–190.

American Society for Quality. (2006). What does ASQ mean by “social responsibility”? Retrieved from http://www.asq.org/social-responsibility/about/what-is-it.html

Andriof, J., & Waddock, S. (2002). Unfolding stakeholder engagement. In J. Andriof, S. Waddock, B. Husted, & S. S. Rahman (Eds.),Unfolding stakeholder thinking: Theory, responsibility and engagement(pp. 19–42). London, England: Greenleaf.

Arlow, P. (1991). Personal characteristics in college students’ evaluations of business ethics and corporate social responsibility.Journal of Business Ethics,10, 63–69.

Aspen Institute Center for Business Education. (2008). Where will they lead? MBA student attitudes about business & society. Re-trieved from http://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/where-will-they-lead-2008-executive-summary.pdf

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2010).

Business accreditation standards. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/ accreditation/business/standards/aol/learning goals examples.asp Aupperle, K., Carroll, A. B., & Hatfield, J. (1985). An empirical

exam-ination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability.Academy of Management Journal,28, 446–463.

Basu, K., & Palazzo, G. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sensemaking.Academy of Management Review,33, 122–136. Birch, D. (2003). Corporate citizenship, social responsibility, and the new

economics of business sustainability and the revolution of new economics.

Momentum,16(4), 20–22.

Brummer, J. (1983). In defense of social responsibility.Journal of Business Ethics,2, 111–122.

Budner, H. (1987). Ethical orientation of marketing students.The Delta Psi Epsilon Journal,29(3), 91–98.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional model of corporate performance.

Academy of Management Review,4, 497–505.

Carroll, A. B. (1991, July/August). The pyramid of corporate social respon-sibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders.

Business Horizons,34(4), 39–48.

Davis, J. R., & Welton, R. E. (1991). Professional ethics: Business students’ perceptions.Journal of Business Ethics,10, 451–463.

EFFECT OF A BUSINESS AND SOCIETY COURSE ON STUDENT CSR ATTITUDES 237

Devinney, T. (2009). Is the socially responsible corporation a myth? The good, the bad, and the ugly of corporate social responsibility.Academy of Management Perspectives,23, 44–56.

Drucker, P. (1946).The concept of the corporation. New York, NY: John Day.

Du Plessis, C. J. A. (2008). Ethical failure under the agency logic: Grounding governance reform in a logic of value.Group & Organization Manage-ment,33, 781–804.

Easterly, L., & Miesing, P. (2009). NGOs, social venturing, and community citizenship behavior.Business & Society,48, 538–564.

Felton, E., & Sims, R. (2005). Teaching business ethics: Targeted outputs.

Journal of Business Ethics,60, 377–391.

Freeman, R.E., & Liedtka, J. (1991). Corporate social responsibility: A critical approach.Business Horizons,34, 92–97.

Friedman, M. (1970, September 13). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.The New York Times Magazine, p. 32. Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good

man-agement practices.Academy of Management Learning & Education,4, 75–91.

Giacalone, R., & Thompson, K. (2006). Business ethics and social responsi-bility education: Shifting the worldview.Academy of Management Learn-ing and Education,5, 266–277.

Glenn, J. R. (1992). Can a business and society course affect the ethical judgment of future managers?Journal of Business Ethics,11, 217–223. Goodstein, J., & Wicks, A. (2007). Corporate and stakeholder

responsi-bility: Making business ethics a two-way conversation.Business Ethics Quarterly,17, 375–398.

Gopalakrishnan, S., Mangaliso, M. P., & Butterfield, D. A. (2008). Managing ethically in times of transformation: Challenges and opportunities.Group & Organization Management,33, 756–759.

Greenberg, D., Clair, J., & Maclean, T. (2007). Enacting the role of man-agement professor: Lessons from Athena, Prometheus, and Asclepius.

Academy of Management Learning and Education,6, 439–457. Harrison, J., & Freeman, R. E. (1999). Stakeholders, social

responsibil-ity, and performance: Empirical evidence and theoretical perspectives.

Academy of Management Journal,42, 479–485.

Holland, K. (2009, March 15). Is it time to retrain B-schools?The New York Times, 1–2.

James, H. S. (2006). Self-selection bias in business ethics research.Business Ethics Quarterly,16, 559–577.

Kennedy, M., & Horn, L. (2007). Thoughts on ethics education in the busi-ness school environment: An interview with Dr. Jerry Trapnell, AACSB.

Journal of Academic Ethics,5, 77–83.

Kolb, A., & Kolb, D. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhanc-ing experiential learnEnhanc-ing in higher education.Academy of Management Learning and Education,4, 193–212.

Kraft, K. (1991). The relative importance of social responsibility in deter-mining organizational effectiveness: Student responses.Journal of Busi-ness Ethics,10, 179–188.

Kraft, K., & Singhapakdi, A. (1991). The role of ethics and social responsi-bility in achieving organizational effectiveness: students versus managers.

Journal of Business Ethics,10, 679–686.

Kraft, K., & Singhapakdi, A. (1995). The relative importance of social responsibility in determining organizational effectiveness: Student re-sponses II.Journal of Business Ethics 14, 315–326.

Lawrence, K., Reed, K., & Locander, W. (2011). Experiencing and measur-ing the unteachable: Achievmeasur-ing AACSB learnmeasur-ing assurance requirements in business ethics.Journal of Education for Business,86, 92–99. Loyd, D. L., Kern, M., & Thompson, L. (2005). Classroom research:

Bridg-ing the Ivory Divide.Academy of Management Learning and Education,

4, 8–21.

Luthar, H., & Karri, R. (2005). Exposure to ethics education and the per-ception of linkage between organizational ethical behavior and business outcomes.Journal of Business Ethics,61, 353–368.

McGlone, T., Spain, J., & McGlone, V. (2011). Corporate social responsibil-ity and the millennials.Journal of Education for Business,86, 195–200.

Meehan, J., Meehan, K., & Richards, A. (2006). Corporate social responsi-bility: The 3C-SR Model.International Journal of Social Economics,33, 386–398.

Middleton, D. (2010, May 5). B-schools try makeover. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/ SB10001424052748703961104575226632041894088.html

Middleton, D., & Light, J. (2011, February 3). Harvard changes course: School’s overhaul part of a push to alter elite B-School cultures.

The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/ SB10001424052748704124504576118674203902898.html

Mitroff, I. (2004). An open letter to the deans and the faculties of American business schools.Journal of Business Ethics,54, 185–189.

Moberg, D., & Seabright, M. (2000). The development of moral imagination.

Business Ethics Quarterly,10, 845–884.

Neubaum, D., Pagell, M., Drexler, J., McKee-Ryan, F., & Larson, E. (2009). Business education and its relationship to student personal moral philoso-phies and attitudes toward profits: An empirical response to critics.

Academy of Management Learning and Education,8, 9–24.

Ng, J., White, G., Lee, A., & Moneta, A. (2009). Design and validation of a novel new instrument for measuring the effect of moral intensity on accountants’ propensity to manage earnings.Journal of Business Ethics,

84, 367–387.

Nguyen, N., Basuray, M., Smith, W., Kopka, D., & McCulloh, D. (2008). Ethics perception: Does teaching make a difference?Journal of Education for Business,84(2), 66–75.

Nicholson, C., & DeMoss, M. (2009). Teaching ethics and social responsi-bility: An evaluation of undergraduate business education at the discipline level.Journal of Education for Business,84(4), 213–218.

O’Fallon, M. J., & Butterfield, K. D. (2011). Moral differentiation: Exploring boundaries of the “Monkey See, Monkey Do” perspective.Journal of Business Ethics,102, 379–399.

Pfeffer, J. (2005). Why do bad management theories persist? A comment on Ghoshal.Academy of Management Learning & Education,4, 96–100. Rahdert, K. (1972). Teaching values in higher education dealing with value

controversies.Academy of Management Proceedings,(00650668), 251. Shaffer, B. (1977). The social responsibility of business: A dissent.Business

& Society,XVII, 11–18.

Shaffer, B. (1978). The social responsibility of business: A flawed defense response.Business & Society,XVIII, 41–42.

Simmons, R., Shafer, W., & Snell, R. (2009). Effects of a business ethics elective on Hong Kong undergraduates’ attitudes toward corporate ethics and social responsibility.Business & Society,48(4), 1–32.

Stead, B., & Miller, J. (1988). Can social awareness be increased through business school curricula?Journal of Business Ethics,7, 553–560. Traiser, S., & Eighmy, M. A. (2011). Moral development and narcissism

of private and public university business students.Journal of Business Ethics,99, 325–334.

Valentine, S., & Bateman, C. R. (2011). The impact of ethical ideologies, moral intensity, and social context on sales-based ethical reasoning.

Journal of Business Ethics,102(1), 155–168.

Vogel, D. (1991a). Business ethics: Past and present.Public Interest,102, 49–64.

Vogel, D. (1991b). Business ethics: New perspectives on old problems.

California Management Review,33(4), 101–117.

Waddock, S. (2004). Parallel universes: Companies, academics, and the progress of corporate citizenship.Business and Society Review, 109, 5–42.

Wilhelm, W. (2008). Integrating instruction in ethical reasoning into un-dergraduate business courses.Journal of Business Ethics Education,5, 5–34.

Windsor, D. (2002). Jensen’s approach to stakeholder theory. In J. Andriof, S. Waddock, B. Husted, & S. S. Rahman (Eds.),Unfolding stakeholder thinking: Theory, responsibility and engagement(pp. 85–100). London, England: Greenleaf.

Wynd, W., & Mager, J. (1989). The business and society course: Does it change student attitudes?Journal of Business Ethics,8, 487–491.