www.elsevier.com/locate/econedurev

Nonoptimal use of nontraditional education

Marshall J. Horton

*LeTourneau University, Division of Graduate, Adult, and Continuing Studies, 5710 LBJ Freeway, Suite 150, Dallas, TX 75240, USA

Received 23 March 1998; accepted 8 January 1999

Abstract

Many universities are implementing nontraditional programs for working adults using adjunct, nontraditional faculty as temporary workers. This practice is defended as economically necessary. However, no economic theory of this practice has been developed. In a simple model of private universities with two products, traditional and nontraditional education, surplus is maximized subject to market demand for traditional and nontraditional education. Tuition and faculty staffing are choice variables. Marketing and library services are fixed at predetermined levels. The results are consistent with conventional price theory: to operate optimally, the firm pays each input the value of its marginal product, adjusted by the appropriate price elasticity of demand. If the university is modeled as a firm, traditional education is tuition elastic and nontraditional education is tuition inelastic, then traditional faculty are optimally paid more than nontraditional faculty only when traditional tuition is higher than nontraditional tuition. [JEL Code: L31] 1999 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Nontraditional; Traditional; Adult education; Nonoptimal; Surplus; Market

1. Introduction

Traditional college and university enrollments have been declining throughout the 1990s, primarily because of a lack of 18- to 22-year-old potential students. In response to this drop in enrollment, universities have offered nontraditional programs aimed primarily at working adults1. Nontraditional programs, as defined here, consist of programs marketed specifically toward students over the age of 25 who are working full-time while pursuing a degree. These programs, often offered

* Tel.: 11-972-387-9835; fax: 11-972-387-2811; e-mail: [email protected]

1The Chronicle of Higher Education for June 20, 1997,

quoted a University of Pennsylvania administrator as saying that “even the elite institutions now recognize the threat of com-petition”. Thus Chicago, Duke, Stanford, and Johns Hopkins have joined the ranks of elite universities offering nontraditional programs and distance learning (Blumenstyke, 1997, p. A23).

0272-7757/99/$ - see front matter1999 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. PII: S 0 2 7 2 - 7 7 5 7 ( 9 9 ) 0 0 0 2 6 - 6

at remote sites, employ primarily part-time adjunct fac-ulty who teach accelerated format courses.

Some researchers have pointed out disparities in the way universities treat traditional, full-time faculty and the way they treat nontraditional, part-time faculty (Gappa & Leslie, 1993). In contrast to traditional faculty, it is often the case that nontraditional faculty members are not paid regular, ongoing salaries (their remuneration is more properly termed wages), provided offices, offered job security, or granted benefits. In their book,

The invisible faculty, Gappa and Leslie (1993) cite

uni-versity administrators who justify segregating faculty into traditional and nontraditional roles based on econ-omic necessities. The arguments of Gappa and Leslie were updated in a recent issue of Academe in a Statement from the Conference on the Growing Use of Part-Time and Adjunct Faculty (1998). To date, however, none has modeled the economic basis for such disparate treatment or tried to answer the following questions.

I What is the economic goal of private universities in

I What are significant similarities and differences

between private universities with nontraditional pro-grams and private corporations?

I Is the practice of segregating faculty into ‘haves’ and

‘have-nots’ consistent with the economic goals of private universities?2

Perhaps most frustrating is that the traditional economic theory of the firm seems to have been forgotten when it comes to analyzing the role of nontraditional education and adjunct faculty.

This paper will apply microeconomic principles to address these questions by formulating a simple theoreti-cal model of the private university as a firm with two products: traditional and nontraditional education.

2. Background

James (1990) cited a substantial literature beginning with Breneman (1970) and continuing with Garvin (1980) which assumed that the major goal of a university is prestige maximization. In her own model, James assumed the university wishes to maximize prestige and satisfaction subject to a break-even constraint (p. 85).

While the goal of prestige maximization may be suit-able for major research universities, it may be inappro-priate for small, teaching-oriented private institutions. For those institutions which are more tuition-driven, a different goal may be considered. This paper will assume that policies and perhaps mission are largely dollar-driven, at least for those private universities which receive little research funding and are not as highly ranked academically as the best known research or even doctoral institutions. Consistent with the modern percep-tion that nonprofit entities strive to set aside the excess of revenues over expenditures as surplus (fund balance) toward endowment, the private university is assumed to attempt to maximize surplus subject to production con-straints.3

This is not the first place in which a large subset of modern private universities has been characterized as a business industry.4 Game theorists Brandenburger and Nalebuff (1996) pointed out that even elite institutions

2Horton and Parry (1997) considered the role of adjunct

fac-ulty in Higher Education marketing.

3Admittedly, research universities derive operating revenues

from grants and foundation funds. With the governmental research funding cuts of the 1980s and 1990s, however, these institutions face dwindling sources of research funding. Their presence, moreover, in the market for nontraditional programs, indicates that they are still somewhat enrollment-driven (see Blumenstyke, 1997).

4Ridgeway (1968) characterized American universities as

‘closed corporations’.

may be modeled similarly to businesses. For example, like private corporations, many private universities are dependent upon their customer-students for institutional growth and even existence.

A recent article in The Chronicle of Higher Education noted the growing influence of the profit motive in col-leges and universities. Apollo Group Inc., DeVry Inc., and ITT Educational Services Inc., are the three top for-profit institutions of higher learning, with over 130,000 students between them (Strosnider, 1998). Although the question of the optimal organizational form for univer-sities is beyond the scope of this paper, traditional econ-omic theory would indicate that the explosive growth of private corporations in this area will pressure more and more private, non-profit universities to maximize their fund balances.

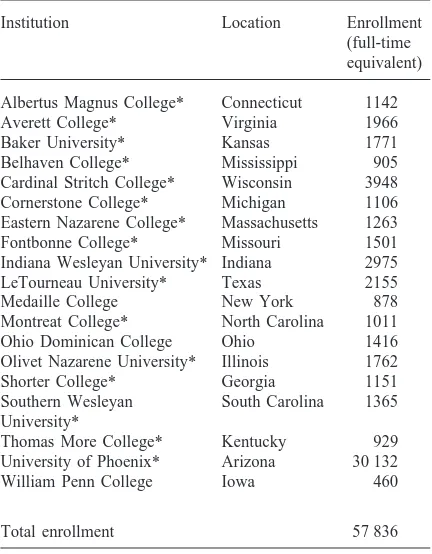

The de-emphasis of the faculty has been accomplished not through the efforts of economists but rather by the followers of one educator: Malcolm Knowles. As the pre-eminent apostle of nontraditional education, Pro-fessor Knowles touted adult learning centers as places where adults could learn using methods tailored to adults. One of the tenets of andragogy, as the method of adult education has come to be called, is that professors are unnecessary for working adult students (Knowles, 1970, 1990). It also happens that libraries, faculty research, and a physical plant are also superfluous for the adult student, according to the andragogical method. This approach has allowed dozens of private institutions to branch out into surrounding metropolitan areas to offer night classes in rented office space with no library resources and only part-time faculty. Nineteen such insti-tutions, representing over 50,000 students, are all mem-bers of The Consortium for the Advancement of Adult Higher Education (C.A.A.H.E.) affiliated with Apollo Group, Inc. The C.A.A.H.E. membership is profiled in Table 1. While this is only a subset of institutions for which the approach in this paper may be considered valid, each of the institutions in Table 1 employs the andragogical method in nontraditional programs for working adults. While Knowles and his followers emphasized their approach for its effectiveness in achieving learning objectives, practical administrators could cut faculty and library expenditures, leaving great sums with which to subsidize traditional programs whose enrollments continued dropping.

3. The model

Table 1

Members of The Consortium for the Advancement of Adult Higher Education, location, and 1996 total enrollment by insti-tution

Institution Location Enrollment

(full-time equivalent)

Albertus Magnus College* Connecticut 1142

Averett College* Virginia 1966

Baker University* Kansas 1771

Belhaven College* Mississippi 905

Cardinal Stritch College* Wisconsin 3948 Cornerstone College* Michigan 1106 Eastern Nazarene College* Massachusetts 1263

Fontbonne College* Missouri 1501

Indiana Wesleyan University* Indiana 2975

LeTourneau University* Texas 2155

Medaille College New York 878

Montreat College* North Carolina 1011

Ohio Dominican College Ohio 1416

Olivet Nazarene University* Illinois 1762

Shorter College* Georgia 1151

Southern Wesleyan South Carolina 1365 University*

Thomas More College* Kentucky 929

University of Phoenix* Arizona 30 132

William Penn College Iowa 460

Total enrollment 57 836

* Denotes institutions regionally accredited to offer masters degrees.

All institutions regionally accredited to offer bachelors degrees. Source of accreditation status: 1997–1998 Accredited

Insti-tutions of Postsecondary Education. American Council on

Edu-cation, Washington, DC.

types of students: traditional (TS) and nontraditional (NS). They do this by hiring appropriate faculty and pro-viding services such as library and learning resources. At present, traditional programs are still using admissions departments for signing up students. While this process merits further modeling, admissions departments are assumed to sign up students. Nontraditional programs, however, have employed full-blown marketing depart-ments to aggressively advertise and seek out working adult students. These marketing departments, frequently affiliated with outside consulting firms such as the Insti-tute for Professional Development (owned by Apollo Group Inc.), are paid a percentage, as high as 40 or 50 percent, of gross tuition revenue.5Furthermore,

nontra-5The efficacy of traditional versus nontraditional admissions

departments is an interesting issue which has not been adequately addressed in the literature. Both are complex pro-cesses beyond the scope of this paper.

ditional students are much less likely to require tra-ditional library services in their studies than tratra-ditional students. Therefore, in this model, the production of tra-ditional students is assumed to be inversely related to traditional tuition rates (t) and directly related to tra-ditional faculty employed (TF) and library resources pur-chased (L). Similarly, the production of nontraditional students is assumed to be inversely related to ditional tuition rates (n) and directly related to nontra-ditional faculty employed (NF) and marketing effort expended (M). Payments to traditional faculty, nontra-ditional faculty, library resources, and marketing effort are symbolized by wt, wn, l, and m, respectively.

The objective function, to maximize surplus, is given by

tTS1nNS2(wtTF1wnNF1lL1mM), (1)

which represents tuition revenue minus cost of faculty, library, and marketing resources. Such variables as physical plant, staff, and administration, while important, may be treated more fully in a more complicated frame-work.6Here, they are not explicitly modeled.

The constraints to which the university is assumed to be subject are

TS5T(t,TF,L), (2)

where∂T/∂t,0,∂T/∂TF, and∂T/∂L > 0.

NS5N(n,NF,M), (3)

where∂N/∂n,0,∂N/∂NF and∂N/∂M > 0.

L5L, (4)

and

M5M. (5)

The Lagrangian function is as follows:

max S5{tTS1nNS2[wtTF1wnNF1lL1mM]

2l*[TS2T(t,TF,L)]2m*[NS2N(n,NF,M)]} (6)

by choosing t, n, TF, and NF.

Regional accrediting bodies are assumed to impose library spending, L. Marketing expenditure, M, is assumed slow-to-change, in keeping with the steep learn-ing curve that academicians have consistently exhibited in this area.

The first order conditions from maximizing Eq. (6) are as follows:

6Administrators and staff members are important, but are

∂S/∂t5TS1l∂T/∂t50 (7)

Assuming that the second-order conditions for a maximum are also met, Eqs. (7)–(10) can be solved for the following equations:

(TS*∂T/∂TF)/(∂T/∂t)5 2wt (13) (NS*∂N/∂NF)/(∂N/∂n)5 2wn. (14) Multiplying both sides of Eq. (13) by 1/t and both sides of Eq. (14) by 1/n,

[(TS*t)/(∂T/∂t)]*∂T/∂TF5 2wt/t (15) [(NS*n)/(∂N/∂n)]*∂N/∂NF5 2wn/n (16) Since (∂T/∂t)/(TS*t) is the tuition elasticity of enrollment

for traditional students (et) and (∂N/∂n)/(NS*n) is the

tui-tion elasticity of enrollment for nontraditui-tional students (en), Eqs. (15) and (16) become

(∂T/∂TF)/uetu5wt/t (17) (∂N/∂NF)/uenu5wn/n. (18) In other words, to operate optimally, the university must pay each class of faculty the proportion of tuition equal to the marginal product of the faculty, adjusted by the tuition elasticity of enrollment for students. This result is analogous to the well-known profit maximization con-dition of microtheory, that to maximize profit, the firm must pay each factor of production the value of its mar-ginal product.

To the extent, however, that traditional education is highly tuition elastic, nontraditional education is rela-tively inelastic, and marginal product of faculty is greater for nontraditional faculty than it is for traditional fac-ulty,7the following condition obtains:

7These conditions are not unlikely. Traditional students are

noted for shopping around. Although top-tier institutions can afford to raise tuition without loss of market share, the emerg-ence and continued popularity of state institutions indicates that the demand for traditional education is rather price elastic. Non-traditional students, on the other hand, want to finish their degrees quickly and conveniently. Often covered by company tuition reimbursement, they are less likely to decrease credits demanded because of a tuition hike than are traditional students. Nontraditional faculty provide a large ‘bang-for-the-buck’ for universities. They cost much less and are able to be exploited on a scale unimaginable for full-time faculty. Therefore, the marginal product of nontraditional faculty may be considered higher than the marginal product of traditional faculty, parti-cularly for ‘hot’ areas such as business administration. Obvi-ously, more empirical work needs to be done in these areas.

wn/n > wt/t. (19)

To operate optimally, the university must pay nontra-ditional faculty a greater proportion of nontranontra-ditional tui-tion proceeds than it pays traditui-tional faculty out of tra-ditional tuition proceeds. The results imply that smaller institutions which implement nontraditional programs to gain students (and these are many) are at risk. If nontra-ditional enrollment outstrips tranontra-ditional enrollment, then the institution maximizes its economic benefit only by paying nontraditional faculty a higher percentage of tui-tion revenue than it pays traditui-tional faculty. But insti-tutions invariably pay full-time faculty much more than part-time faculty. This makes sense only if traditional tuition far exceeds nontraditional tuition, which is usu-ally not the case.

Some may find it incredulous that a private university can perform better if it pays part-time faculty more. For a small, private university which employs both tra-ditional and nontratra-ditional faculty, the conventional wis-dom of long-term financial enhancement by relying on adjunct faculty is wrong. The situation is analogous to that of private industry: as the tastes of consumers (students) change and barriers to entry fall (more lax accreditation standards) the firm (the university) simply cannot afford to treat its most valuable resources (faculty) in a shabby or cavalier fashion, as pointed out in Horton and Parry (1997).

Private university administrators of small to medium sized institutions may find a valuable lesson here. Stan-dard microeconomic theory of the firm dictates that when a market becomes more competitive, those who wish to maximize profit (or funds balance) must pay each factor of production the value of its marginal product. Failure to do so, specifically by exploiting adjunct faculty, will have the customer-students questioning just what their ever-increasing tuition bills are financing, if not their tea-chers.8As the situation approaches perfect competition, those institutions unwilling to adjust by paying faculty proportionately more will be forced to shut down.

4. Conclusion

Private universities which implement nontraditional programs for working adults typically staff such pro-grams with part-time, adjunct faculty. These faculty are paid wages, but are not paid permanent salaries, provided with offices, granted tenure, or given benefits. Some

8Walker (1998) pointed out that institutions which have

researchers have argued that, out of fairness, adjunct fac-ulty should be paid more, since nontraditional tuition rates may exceed nontraditional tuition rates, even though the cost of library services and physical plant is far less for nontraditional programs than for traditional programs. Administrators respond that because of econ-omic considerations, they cannot afford to pay nontra-ditional faculty more.

The model outlined in this paper, however, suggests that a policy which establishes nontraditional faculty may be the result of a false economy, consistent with the findings of Gappa and Leslie (1993). Rather than pay nontraditional faculty less, the institution which is maxi-mizing its surplus funds subject to market constraints will pay nontraditional faculty proportionately more than traditional faculty, rather than less. These results can be extended through

1. considering marketing expenditures for nontraditional programs a fixed percentage of nontraditional tuition revenue, as is currently the case with many such pro-grams,

2. examining empirical evidence, such as pay rates, staffing levels, tuition rates, and growth of unrestric-ted endowment among private institutions with both traditional and nontraditional programs,

3. expanding the current model to consider academic prestige over funding, as other studies have assumed for traditional programs, and

4. examining the optimal organizational form of the private university.

If the results of the model are accepted, then those universities which continue to exploit adjunct faculty do so to the institution’s detriment, since such a practice results in inefficiency. For a school which faces little competition, this may be a minor consideration. For those institutions in increasingly competitive markets, such inefficiency may prove fatal.

References

Blumenstyke, G. (1997). Some elite private universities get seri-ous about distance learning. The Chronicle of Higher

Edu-cation XLIII, 41, A23–A24.

Brandenburger, A. M., & Nalebuff, B. J. (1996). Co-opetition. New York: Doubleday.

Breneman, D. (1970). An economic theory of Ph.D. production:

the case at Berkeley. Berkeley: Ford Foundation Program

for Research in University Administration, University of California.

Gappa, J. M., & Leslie, D. W. (1993). The invisible faculty:

improving the status of part-timers in higher education. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Garvin, D. (1980). The economics of university behavior. New York: Academic Press.

Horton, M. J., & Parry, A. E. (1997). The fall and rise of the faculty: product development in lean times. Journal of

Con-tinuing Higher Education, 45(1), 15–21.

James, E. (1990). Decision processes and priorities in higher education. In S. A. Hoenack, & E. L. Collins, The

econom-ics of American universities: management, operations, and fiscal environment (Chapter 4, pp. 77–106). Albany: The

State University of New York Press.

Knowles, M. (1970). The modern practice of adult education:

from pedagogy to andragogy. New York: Association Press.

Knowles, M. (1990). The adult learner: a neglected species (4th ed.). Houston: Gulf Publishing Company.

Ridgeway, J. (1968). The closed corporation: American

univer-sities in crisis. New York: Random House.

Statement from the Conference on the Growing Use of Part-Time and Adjunct Faculty (1998). Academe, January–Feb-ruary, 84(1), 54–60.

Strosnider, K. (1998). For-profit higher education sees booming enrollments and revenues. The Chronicle of Higher

Edu-cation XLIV, 20, A36–A38.

Walker, P. A. (1998). The economic imperatives for using more full-time and fewer adjunct professors. The Chronicle of