COMMENTARY

Putting postmodernity into practice: endogenous

development and the role of traditional cultures in the rural

development of marginal regions

T.N. Jenkins *

Institute of Rural Studies,Uni6ersity of Wales,Aberystwyth SY23 3AL, UK Received 2 February 2000; received in revised form 14 April 2000; accepted 21 April 2000

Abstract

Post-modernity has led to a re-evaluation of tradition. This paper considers one aspect of this re-evaluation — the role of traditional cultures and their implications for a rural development process which is economically, socially and environmentally sustainable in the marginal regions of Europe. The links between traditional cultures, territoriality and sustainability suggest that a culturally homogeneous world is an unattractive prospect in sustainable development terms. Actor-network theory is explored as an approach which can be used to inform policy, in particular by conceptualising how a re-valorisation of cultural resources can provide local actors with strategic capacity for endogenous development and for the harnessing of extra-local forces in a market economy. Against this background, current European Union agricultural policy directions are considered, and an alternative approach is proposed under which traditional cultures are explicitly treated as resources in the creation of rural development networks. Such networks treat territorial locality as an asset, facilitate the animation of local and regional development, and connect localities and local actors with wider national and international markets and development frameworks. The rural development path for marginal regions that emerges integrates tradition with the imperatives of the postmodern world in which economic rationality is combined with an appropriate degree of local developmental control. © 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Traditional cultures; Endogenous development; Territoriality; Rural policy

www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

1. Introduction

Max Weber characterised the shift from tradi-tional (often religious) values to modern ones as the ‘pervasive rationalisation’ of all spheres of society, and the process of modernisation as the ‘institutionalisation of purposive-rational

eco-* Tel.: +44-1970-622247; fax:+44-1970-622958. E-mail address:[email protected] (T.N. Jenkins).

nomic and administrative action’ (Habermas,

1987). Subsequent theorists have stylised

modernity into a general model of evolutionary social development (Coleman, 1968) in which the core societal goal is economic growth rather than survival in harmony with natural surroundings, and the dominant individual goal is achievement through income and consumption rather than through moral standing. An inevitable character-istic of modernisation for both Weber and his successors is the dramatic devaluation of tradition through universalisation of norms of action, gen-eralisation of values, and individual-based pat-terns of socialisation. Tradition has become, at best, a way of presenting the past as an increas-ingly scarce non-renewable resource and, at worst, an impediment to progress.

Yet, an important postmodern insight is that tradition also concerns what Halbwach (1980) terms ‘pastness’ — a renewable resource of cur-rent validity (Appadurai, 1981; Appadurai et al., 1991). The human values embodied in tradition are not only the ‘scars of the past’ but also the ‘portents of the future’ (Pulliam and Dunford, 1980). One might even define postmodernity in terms of its separation of the cultural premises of modernity from its functional consequences; by challenging the validity of the former, post-modernity de-emphasises instrumental rationality and brings a shift in basic values towards what Inglehart (1997) calls ‘existential security’. The postmodern emphasis on subjective well-being, environmental protection and other quality of life concerns has led to a re-evaluation of tradition, reinforced by a tendency towards the removal of the artificial structures of nation-states in favour of more natural ethnic or spatial communities within a pluralist framework (see Jones and Keat-ing (1995), for the case of the European Union). Despite the universalising tendencies of mod-ernisation, EU marginal areas retain traditional

cultures1, exhibiting varying degrees of vigour,

which potentially represent resources for alterna-tives to the modernist cosmopolitan mode of eco-nomic development. Yet, social analysis has largely been dominated by rational behaviour models which abstract economic action from its historical and cultural contexts. Even in early political economy, opinions on cultural diversity were ambivalent. J.S. Mill, for example, recog-nised Europe’s indebtedness for its ‘‘progressive and many-sided development’’ to the ‘‘plurality of paths’’ resulting from its cultural diversity (Feyer-abend, 1987, p. 33); yet Mill also assumed that it would be unequivocally beneficial for minorities in Europe to be brought out of their own ‘‘little mental orbit … (into the) … current of the ideas and feelings … (of more) civilised and cultivated’’ majorities (Kymlicka, 1995, p. 5). Furthermore, the importance of deciphering the structures and processes of the local and the temporal is an article of faith for postmodernism.

The rest of this paper is in four sections. Some of the links between traditional cultures, territori-ality and sustainability are considered in Section 2. A powerful reason for the neglect of traditional cultures may lie in the absence of well-developed theoretical approaches to assessing their role, eco-nomic potential and policy implications, and one such approach is explored in Section 3. An alter-native to the direction taken by current EU agri-cultural policy is proposed in Section 4. Section 5 draws some conclusions.

2. Traditional cultures and sustainable development

In modern social analysis, attempts to take account of ‘culture’ have largely been confined to: (i) assuming that traditions inhibit entrepreneur-ship and constrain developmental economic activ-ity (Hoselitz, 1952; Hagen, 1980); (ii) relating economic outcomes to societal or civic character-istics assumed to be the result of an historical accumulation of social capital (Ishikawa, 1981; Putnam, 1993); or (iii) disentangling the complex interaction between economic performance and its cultural context as revealed in people’s attitudes and values (Bauer, 1984; Inglehart, 1997). Never-1Although not all European regions contain thriving and

theless, ‘‘the conviction that ‘culture matters’ re-mains pervasive in the underworld of develop-ment thought and practice’’ (Ruttan, 1988, p. 56), and its treatment on an intuitive rather than analytical level is ‘‘a deficiency in (develop-ment practitioners’) professional capacity rather than …, evidence that culture does not matter’’ (Ruttan, 1988, p. 256). A persistent view among economists is that culture can be subsumed in ‘tastes’ which are treated as given and outside the frame of economic analysis; that cultures are somehow separate from, and unaffected by, de-velopment values; and that cultural diversity is of no economic importance. Although the mod-ernist assumption of the cultural neutrality of progress has now been comprehensively under-mined by anthropological and historical research (Toulmin, 1990), suggestions for relating cultural endowments to resources, technology and insti-tutions (e.g. as in the induced innovation model of Hayami and Ruttan, 1985) tend to be illus-trative and preliminary.

Anthropology is the social science for which ‘culture’ is the central, albeit disputed, analytical concept. Early anthropological definitions took a bounded and locational view of culture, stress-ing its behavioural, perceptual and material

as-pects and, above all, its territoriality and

association with specific communities (Milton, 1996). With few exceptions, anthropologists have studied culture and its context at the local level, seeing the world as a ‘cultural mosaic’ (Han-nerz, 1992) of traditional cultures and inherited

values — a concept echoed in Norgaard’s

‘patchwork quilt’ view of cultures (Norgaard, 1994). However, the greatly reduced importance of territorial boundaries in an age of increas-ingly available international communication has prompted post-structuralist anthropologists to abandon the traditional locational model and to see culture in unbounded and de-territorialised terms. This approach distinguishes culture’s non-observable elements (perceptions, values, ideas and knowledge which colour people’s under-standing of experience) from observable social processes and structures, and it focuses attention

on the fact that culture is communicated

through relationships rather than inheritance (Hannerz, 1990). The result has been an exten-sion of the concept of culture to include hybrid cultures (e.g. imported religious practices and beliefs that have merged with indigenous ones), de-contextualised cultures (e.g. the vestiges of cultures retained by emigre´s) and, most impor-tantly, ‘trans-national culture’ (e.g. ‘Western’ or ‘modernist’ culture) and cultures reflecting com-munities of interest (e.g. the ‘cultures’ of inter-national bankers or academics). This shift to approaching culture in interpretative terms in re-sponse to the diminished importance of territo-rial boundaries has freed anthropology from its territorial focus and allowed it to consider cul-ture in a global context. It has, however, caused two important difficulties in a postmodern con-text in which tradition is being re-evaluated. The first is that the separation of knowledge from

action (recalling the Cartesian duality of mind/

body and humanity/nature) contrasts with much

empirical observation, creates difficulties for so-cial science modelling of the links between cul-tural endowments, resources, technology and institutions, and is anathema to the philosophi-cal bent of many environmentalists. The second is that the de-territorialisation of culture ob-scures anthropological insights into the purpose of traditional cultures. To illustrate this, it is useful to examine the association (negative or positive) of culture with sustainability.

link between ecosystemicness and sustainability has come to be associated with anti-industrial sentiments and feelings of sympathy for ‘back-ward’ indigenous populations under pressure from more ‘advanced’ majorities. It may also be the result of the casual observation that ‘ecosys-temic’ populations do not radically modify their environments over time, and of the desire for

model solutions to sustainability problems.

Clearly, primitive ecological wisdom is difficult to associate with non-traditional cultures, and mod-ern anthropology has sought to undermine it on the grounds that humans ‘‘have no natural propensity for living sustainably with their envi-ronment’’ (Milton, 1996, p. 222). Rather than a cultural goal, ecological benignness may be an incidental outcome of factors such as low popula-tion density, remoteness, or lack of access to trade and technology. Nevertheless, for a significant proportion of humanity until comparatively re-cently, traditional practices appear to have led to a long-standing, yet highly productive, relation-ship with the land (see King, 1933, for the exam-ple of East Asia).

The second, more persuasive, set of reasons for viewing traditional cultures positively in the light of sustainable development results from the per-ception of such cultures as established ‘‘system(s) of values, beliefs, artifacts and artforms which sustain social organisation and rationalise action’’ (Norgaard, 1994, p. 90). The systems view goes beyond cultures as collections of separable be-havioural, perceptual and practical phenomena and highlights their self-organisation and struc-tured and bounded relationships. General systems theory defines a system as a ‘‘complex unit in space and time whose sub-units co-operate to preserve its integrity, structure and behaviour’’ (Weiss, 1971, p. 99). Individual systems are dedi-cated to the maintenance of the larger systems of which they are part and the smaller systems which comprise them as a pre-requisite for the preserva-tion of their own integrity and stability (von Bertalanffy, 1962). The ‘integrity’ and ‘stability’ concepts strongly recall the Leopoldian ‘land ethic’ (Leopold, 1994), while relations between sub-systems are of particular interest in the con-text of minority cultures — i.e. sub-national

cul-tures of numerically weak populations within nation-states, usually located within specific geo-graphical regions, and frequently retaining their own language (Eliot, 1948). When applied to cul-tures as systems, the systemic characteristics of self-preservation over time and dynamic inter-sys-tem relationships tend to have important implica-tions. These include implications for resource use (materials recycling and cyclic food chains tend to be built into traditional cultures); social organisa-tion (ties, relaorganisa-tionships and obligaorganisa-tions tend to be more important than individualism in societies with strong traditional cultures); external relations (dependence on outside forces tends to be limited in a strategic attempt to maintain systemic homeostasis2

); and sustainability policy (a cultural component cannot be removed from its context without disrupting the set of relationships within which it is embedded, nor imported into another context without disturbing the new surroundings). By contrast, de-territorialised non-traditional cultures generally have negative associations with sustainability because of their shortcomings as

systems. The trans-national ‘culture of

modernity’, in particular, although defended by some social philosophers such as Habermas (Out-hwaite, 1996), has been savaged by many others

such as Giddens (1990).3 Their attack is largely

centred on its technocratic, e´litist, and inherently globalising Cartesian tendency to replace a diver-sity of traditional ideas with the uniformity of cultural universals, and its assumption that people

2The ability to maintain stability (in the sense of both

resistance and resilience) by their own efforts (Odum, 1969). A weakness of general systems theory in this context may lie in the presumption of systems’ homeostatic equilibrium with their environments, a presumption which, when applied to cultures, may fail to account for cultural change (Norgaard, 1994). However, a co-evolutionary progression of social and environmental systems does not seem to preclude a dynamic equilibrium between a culture and its environment.

3An argument is often made for a cosmopolitan alternative

from all traditions have access to the same cultur-ally-neutral basic conceptual framework. The cul-ture of modernity has become the third pillar (alongside economics and politics) in the ‘unholy trinity’ of mechanisms that integrate world sys-tems at a global level (Wallerstein, 1990) without regard for local specificities. It is seen as a me´lange of disparate, contextless components with neither temporal nor locational foundation, where collective memories and generational suc-cession are unimportant, where no ‘sacred land-scapes’ or ‘golden ages’ are available for use as reference points (Smith, 1990; Hamilton, 1994), and where reliance is placed on overwhelming technological and institutional force (Jenkins, 1998). Under this view, the flows and relation-ships associated with the culture of modernity are the uni-dimensional ones of economic exchange and innovation, and its competitive success is associated with the high value attached to short-term rewards without regard for long-short-term conse-quences (recalling the ‘defective telescopic faculty’ attributed to modern humanity by Pigou). In system terms, the culture of modernity suffers from lack of context and of sensitivity to its systemic environment, uni-dimensionality, uni-di-rectionality, and short-sightedness.

A fundamental anthropological contention con-cerning the purpose of traditional cultures is that culture is interposed by humanity between itself and its environment in order to ensure its security and survival (Carneiro, 1968) and to preserve lasting order (Gans, 1985). The criterion for cul-tural ‘success’, therefore, can be seen in terms of what Rappaport (1971) terms ‘adaptive effective-ness’, under which cultures ensure adaptive

hu-man behaviour in relation to a societal

development path sanctioned by the collective conscience (Harrison, 1927). Durham (1976, p. 101) suggests that cultural and biological traits co-evolve to enhance the ‘inclusive fitness’ of hu-manity in its environment: ‘‘By providing a means of adaptation which is both … constant in stable environments and … flexible in changing environ-ments, culture can … greatly enhance the ability of social behaviour to track environmental condi-tions’’. As a result, the evolutionary advantages of cultural diversity have received particular

anthro-pological recognition (Milton, 1996). Natural di-versity means didi-versity in the gene pools of species, more probability of adaptation to chang-ing conditions, and hence species’ survival under a wide variety of conditions. Cultural diversity strengthens natural diversity by enabling diverse ways of comprehending experience and interact-ing with environments, providinteract-ing different

possi-bilities for human futures (Keesing, 1981),

allowing more flexible use of global resources (Jacob, 1982), and potentially leading to a variety of sustainable societies (IUCN et al., 1991). Cul-tural diversity is also akin to intellectual diversity and multi-disciplinarity, the value of which is based on the assumption that understanding is increased when issues are viewed from different perspectives.

In addition to servicing systemic reproduction and providing humanity with the behavioural means to evolutionary advantage, cultures have two more contentious instrumental roles. The first lies in their potential for mobilising collective

energies4, emphasised in Weber’s (1976) focus on

the ‘motivational’ aspects of culture for economic development. The second lies in their production of a sense of common destiny (Smith, 1990) which underwrites social integration (Bauman, 1989). This has led some to argue for culture as a ‘basic need’: ‘‘Among elementary human needs — as basic as those for food, shelter, security, procre-ation, communication — is the need to belong to a particular group, united by some common links — especially language, collective memories, con-tinuous life upon the same soil, … a sense of common mission’’ (18th century historian Johann Gottfried von Herder, quoted in Berlin, 1980, p. 252, 257). It also leads to the ‘social capital’ view of culture (i.e. the importance of networks, trust and association) derived from Alexis de Toc-queville (Putnam, 1993; Day, 1996) which

sug-gests that local cultures are important

mechanisms in the dispersion of economic control and in increased local autonomy, both supported

4Not necessarily benevolent ones, as the Nazi period in

by sustainable development theorists and the logic of Agenda 21, and facilitated by increasingly so-phisticated information technology. Both the mo-tivational and social capital roles of cultures resurface in current discussion of the economic position of disadvantaged regions in an increas-ingly competitive EU (Committee of the Regions, 1996). In particular, it is argued that socially, cultural rootedness is based upon belonging rather than upon accomplishment and therefore forms a secure plank in the platform of human self-identity; politically, cultural vibrancy can be a stimulating source of cohesion and of long-term confidence that the networks involved are sustain-able over time; and economically, cultural assets are exploitable through product differentiation in the quest for market share. These can be signifi-cant factors in development, leading regions to make long-term investments and to forge eco-nomic relations with the outside world (Bassand, 1993).

In view of these important claims regarding the purpose and potential of traditional cultures, a culturally homogenous world appears unattractive in sustainable development terms. Although the continuing existence of traditional cultures in rural areas guarantees neither sustainability nor economic vibrancy, such cultures have character-istics which improve the probability of sustainable ways of living and developing. The sustainability debate has taught that economic, social and envi-ronmental problems and, more importantly, their solutions are as much cultural as technological and institutional. Cultural diversity, therefore, of-fers humanity a variety of ways of developmental interaction and avoids the difficulties associated with any monoculture — namely, a loss of mate-rial for new paths of economic, social and envi-ronmental evolution, and a danger that resistance to unforeseen problems is lowered. A policy re-quirement of cultural diversity seems justifiable, therefore, in general sustainable development terms; taking a Hicksian view of sustainability, cultural diversity increases the probability that human societies develop without undermining their economic, social or environmental capital bases.

3. Traditional cultures and endogenous development

The nature of economic activity is changing in Europe’s rural areas, a change conceptualised as

the ‘post-productivist transition’ (Ilbery and

Kneafsey, 1997) in which rural people need to seek alternative ways of making a sustainable livelihood less heavily dependent on publicly-sup-ported agricultural production. Yet, the logic of modernism and globalisation has caused many of Europe’s localities to perceive themselves as disfa-voured by national policy or other external forces. Further, by devaluing traditional cultures, mod-ernism has reduced the importance of locality by replacing the large array of local knowledge sys-tems and techniques with an exclusive normative technological system of interlinked innovations (van der Ploeg, 1992). The extent of the discon-nection between farming practice and locality has varied between regions according to their individ-ual social, technological, locational and resource circumstances, but in general terms the weakness of locality is reflected in the fact that external technological and market circumstances come to represent the conceptual standard against which the utility of local resources is judged.

Far from traditional cultures being ‘ethnographic monuments’ (in Engels’ disdainful phrase), tradi-tion, myth, values and symbol can be made ‘avail-able’ to consumers through products and images that reflect multiple forms of alternative social identity. In this sense, cultural diversity is an economic asset which, marketed appropriately, can generate sustainable income and employment (Committee of the Regions, 1996).

Exploitation of cultural diversity for rural de-velopment can be taken still further as a complex endogenous process. The ethnic cores of tradition engraved on the popular consciousness of rural society give weight to ‘cultural markers’ (Ray, 1998), such as traditional products and produc-tion methods, local languages and folklore, and historic sites and landscapes. Their role has three important dimensions; instrumentally, they are assets to be exploited or conserved; representa-tionally, they define territorial identity to the out-side world; and inspirationally, they are a source of local ethics and motivation. Endogenous devel-opment can be characterised as a bottom-up pro-cess that uses all three dimensions of cultural markers as key resources. The process recognises cultural models as indispensable local resources which structure the interpretation of extra-local forces and determine local practices in terms of local needs and solutions to local problems (Feyerabend, 1987). Under endogenous develop-ment, the extra-local is deconstructed and recom-posed to suit local conditions, perspectives and interests (Iacoponi et al., 1995), and local re-sources thereby become the conceptual standard against which the utility of the extra-local is eval-uated. In practical terms, by making best use of local resources such as people and local knowl-edge, endogenous development is claimed to have the potential to create more employment than modernist development forms (van Dijk and van der Ploeg, 1995), and to result in positive ap-proaches to environmental conservation, product quality, efficiency of resource use, and retention of value generated locally. Further, under a com-prehensive view of costs, endogenous develop-ment may potentially be cost-effective even in conventional economic terms and before taking account of its environmental, social and

employ-ment benefits (van der Ploeg and Saccomandi, 1995).

The conceptualisation of endogenous develop-ment can be sharpened by the use of Actor-Net-work Theory (ANT) (Cooke and Morgan, 1993; Murdoch, 1995). Farming, for example, can be seen as the point of intersection of various do-mains, including the natural world, the family, the local community, the market, the world of tech-nology, and the world of policy. Farmers establish networks within these domains, thus defining an interactive space that goes beyond the simple commercial networks with which neo-classical economics is concerned. Livestock producers in rural Wales, for example, faced with severe mar-keting difficulties associated with negative secular trends in red-meat consumption, have established innovative networks with other producers, institu-tions, and consumers in order to differentiate their products and develop market niches (Jenkins and Parrott, 1998; Ilbery and Kneafsey, 1999). An important element of this networking is the trans-formation of natural resources and symbolic rep-resentations (such as unspoilt landscapes) into marketable products. This process requires what Harvey (1989) calls ‘structured coherence’ of sym-bolic capital, shared ideologies and patterns of interaction which can motivate local actors to create appropriate networks and ensure that products embody locality. In principle, such co-herence resides within traditional cultures in which the transmission of values via relationships is crucial (Hannerz, 1990), and it provides local actors with strategic capacity reaching beyond passive acceptance of the conventional market

and technological relations proposed by

modernity. ANT emphasises that market relations and the exchange of goods are embedded in a broader set of socio-cultural relations which are especially apparent in rural areas. Social defini-tions of moral behaviour and of quality (of life, production processes and products), for example, are crucial elements in the forging and sustaining of networks, and traditional cultures represent one mechanism by which the required social cohe-sion is acquired.

development’s crucial dependence on linkages with the extra-local, as represented by markets, technology, policy, social trends, and (in the EU) availability of structural funding. Such networks can represent enabling opportunities, and local control of access to them enables local actors to undertake and sustain a distinctive way of life. From a practical standpoint, local strategies for the exploitation of niche markets, such as those for speciality foods or handcrafts, can be devel-oped through the use of appropriate extra-local product differentiation and marketing techniques (OECD, 1995; Ilbery and Kneafsey, 1999); while from a conceptual viewpoint, local character can be translated into intellectual property through the use of extra-local regulatory frameworks such as the appellation d’origine controˆle´e system for French wines (Moran, 1993). The dynamic ten-sion of inter-relations between the local and the extra-local forms much of the arena in which strategic choices can be made. Yet this tends to be neglected in conventional agricultural economic analysis which, despite empirically observable variability in the degrees of commoditisation practiced in different localities, treats each rural economic activity as a process to be optimised in relation to prevailing price and market relations. van der Ploeg (1992) shows that styles of farming, for example, vary in their technical and market orientation and are not simply derived from pre-vailing market and technological conditions. They are best seen as ‘multi-dimensional social con-structions’, part of the ‘cultural repertoire’ of rural communities, and the outcome of strategic reasoning by producers and communities medi-ated through networks of communication, co-op-eration and co-ordination. As the Welsh livestock example shows, the strategic consequences of net-work inter-relations are increasingly important for rural regions at a time of unfavourable product markets, food safety problems, and environmental concern.

An ANT-based theory of rural development, therefore, considers the nature of the association between economic actors and the interactive bal-ance between local and extra-local forces. It high-lights the costs involved in network interaction, the power relations involved, and the extraction

of value; and it can provide strategic guidance on local resource use, institutional intervention, tech-nological innovation, and the conditions under which local actors can retain control and value. Under the conventional modernist model of agri-culture, the distribution of control and value-added are perceived as increasingly in favour of the extra-local, forcing further decline on Eu-rope’s marginal rural regions. Re-valorisation of the local through endogenous development, how-ever, suggests that differentials of power and value-retention can be shifted in favour of the local. The growing diversification of production and consumption activity in rural areas means that rural resources have the opportunity to ‘re-define their own use and exchange value’ (Mars-den et al., 1992) through an increase in the significance of local distinctiveness brought about by a forging of networks for postmodern eco-nomic ends.

4. Rural development and EU agricultural policy

Despite strong initial cultural roots (Tracy, 1989), EU policy towards agriculture has shown little subsequent sensitivity towards ensuring a flourishing of the ‘domains’ within which tradi-tional and localised cultures have evolved, where cultural capital is economically important, and

where ‘cultural multipliers’5 are particularly

strong. In the context of this paper, the important issues are as follows. From its inception until 1992, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) concentrated largely on meeting farm income ob-jectives and on controlling the production sur-pluses that arose in some sectors. Policy support was concentrated primarily on regions and pro-ducers facing no particular disadvantage, and consequently rural communities in marginal re-gions suffered disproportionately from decline in agricultural activity. To the extent that such

re-5Cultural multipliers are particularly important where

gions and communities were repositories of tra-ditional cultures, negative cultural consequences were an important outcome. More recently, starting with the 1992 reforms and continuing with the Agenda 2000 proposals (Commission of the European Communities, 1997, 1998), aware-ness has grown of the diversity of European agriculture in terms of resource endowments, farming methods and farming traditions. Policy has increasingly sought to give EU member states the means of taking better account of lo-cal conditions, subject to avoidance of

distor-tions to competition and undermining of

common policy management. The current CAP, therefore, has two strands. The first (competi-tiveness) strand is a response to external factors, and is principally characterised by lower product prices. The external pressures include the bud-getary implications of EU enlargement, and the world market oppurtunities, competitive pres-sures and international obligations of trade lib-eralisation. The second (safeguards) strand is a response to the internal consequences of lower product prices by means of compensatory pay-ments to farmers. The aims include shielding the most vunerable farmers from effects of lower prices, promoting rural development, and safe-guarding rural communities and the natural en-vironment.

Although there are EU policies designed for the maintenance and development of Europe’s cultural wealth and traditions, overt support for cultural diversity is not a feature of the re-formed CAP. In broad terms, its

competitive-ness strand has potentially damaging

implications for cultural diversity and the valori-sation of the local through endogenous develop-ment; while its safeguards strand has potentially positive impacts, largely manifested through ter-ritorial designations for Structural Fund pur-poses (e.g. the Objective 1 and Objective 5b development areas). The model of rural areas which the CAP seeks to promote gives priority to an agricultural sector that can compete on world markets, together with support expendi-ture that explicitly recognises the multi-func-tional nature of agriculture, especially its role in

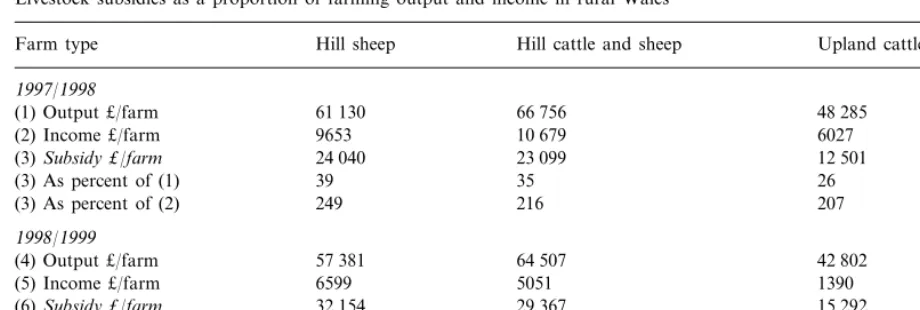

environmental care and its contribution to em-ployment and incomes in rural areas. In terms of the theme of this paper, the model has a number of important shortcomings. It is self-consciously interventionist rather than ethically-driven; intervention increasingly needs to be justified in cost-benefit terms in relation to the value of the public goods and services provided in rural areas; and traditional cultures are there-fore constantly vulnerable to political whim and budgetary pressure. The result is that farmers operate in a policy environment that is per-ceived as short-term, unstable and uncertain, and therefore unconducive to long-term invest-ment (Clark, 1997). Equally, farmers operate in the knowledge that they survive on sufferance, dependent on public subsidy and welfare, a point illustrated for rural Wales in Table 1.

The arguments of this paper suggest an alter-native view of rural development to that under-lying the CAP, a view which coincides with what Ray (1998) terms the ‘culture economy’ approach to rural development. Under this ap-proach, traditional cultures are explicitly treated as resources for rural development networks, rather than as legacies to be conserved. The ap-proach has two strands. First, a traditional cul-ture can be turned outwards and marketed, either explicitly as an engine of development to attract inward investment or regional develop-ment assistance, or implicitly in the form of products and services with a cultural compo-nent. Table 2 gives examples, in selected rural regions in the EU, of such products and ser-vices, all of which involve complex production, marketing, institutional and consumer networks. Such outward-looking culture economy strate-gies, with origins in Weber’s ‘motivational’

as-pects of culture, directly connect territorial

Table 1

Livestock subsidies as a proportion of farming output and income in rural Walesa

Hill cattle and sheep

Farm type Hill sheep Upland cattle and sheep

1997/1998

66 756

61 130 48 285

(1) Output £/farm

10 679

(2) Income £/farm 9653 6027

23 099

24 040 12 501

(3)Subsidy £/farm

(3) As percent of (1) 39 35 26

216 207

249 (3) As percent of (2)

1998/1999

64 507

57 381 42 802

(4) Output £/farm

(5) Income £/farm 6599 5051 1390

29 367

32 154 15 292

(6)Subsidy £/farm

56

(6) As percent of (4) 46 36

(6) As percent of (5) 487 581 1100

aSubsidy includes hill livestock compensatory allowances, sheep annual premia and suckler cow premia. Income is net farm

income, excluding breeding livestock stock appreciation. Source, Jenkins (1999).

programmes, although these currently represent a minuscule proportion of total EU rural funding (Midmore, 1998). The result is a participatory form of development, which involves the mobili-sation of both socio-cultural and economic net-works and the embedding of development in existing stable and lasting socio-cultural and eco-nomic structures. Such local animation can also provide communities with the will, rationale and power to resist the encroachment of inappropriate trends in modernity where these clash destruc-tively with local ethics. In contrast to the CAP approach, this culture economy view of rural development integrates farming closely into local rural economies and produces a long-term view whose stability and certainty is conducive to long-term investment by local actors and communities and by outside agencies. It also means that local economic actors are perceived as less dependent on public subsidy and on outside political whim and budgetary pressures. Traditional cultures are then less vulnerable to decline, linked productively with development, and able to realise their poten-tial for enhancing social, economic and

environ-mental sustainability. The culture economy

provides a networking framework in which local actors can develop strategies for integrating local economies with external markets and for pursuing development paths which accord with local val-ues.

5. Concluding note

The futures available to a society are not only those ‘nostalgic’ futures which can be passively forecast, but also include what Bertrand de Jou-venel has termed ‘futuribles’ — i.e. the ‘imagina-tive’ futures which society actively creates through its attitudes and policies (Toulmin, 1990). In its critique of modernist assumptions, postmodernity proposes imaginative futures, among which is a re-establishment of the value of territoriality from developmental, consumer and sustainability per-spectives. It suggests a re-evaluation of the

valid-ity of traditional notions of cultures as

Table 2

Products and services with a cultural component from selected EU rural regionsa

Finland

South Ostrobothnia region Farm cheese Furniture Carpets

Northern Savo region Suonenjoki region strawberries Rural tourism

Vendace (a fresh fish,Coregonus albula)

France

Dairy produce (AOC)b

Basse Normandie region

Cider and calvados (AOCPays d’Auge) Equestrian tourism

Auvergne region Lentils (AOClentilles6ertes du Puy) Bourbonnais Charolais beef (Label rouge) Cantal and Salers cheeses

Rural tourism

Greece

Currants Achaia region

Organic currants

Moschofilero grapes and wine Arkadia region

Organic Moschofilero grapes and wine

Ireland

Farmhouse cheese Southwest region

Speciality gourmet foods Wild and farmed shellfish Handcrafts

Rural tourism Northwest region

Handcrafts Organic produce

Spain

Rural tourism Valencia region

Wine (DOC) Troncho´n cheese Teruel region

Virgin olive oil Teruel ham

UK

West Wales region Red meatsc

Farmhouse cheeses Organic produce Handcrafts Beef Grampian region

Shortbread and oatcakes Rural tourism

Seafish and seafish products

aSources: Jenkins and Parrott (1998), Ilbery and Kneafsey (1999). bCamembert,Pont-l’E´6eˆqueandLi6arotcheeses,Isigny cream and butter.

cLamb and beef.

and marketing of such products enhances

net-works consistent with market-led rural

development.

cul-tural diversity and environmental degradation. Not only do they both directly affect human well-being and quality of life, the manner of their arrest and reversal is crucial to their contribution to such well-being. In the environmental field, nature re-serves and compensating projects are popular devices for maintaining the aggregate level of environmental capital, yet it is doubtful whether such devices are as good as the ‘real thing’, such as a countryside fashioned from traditional, but living and evolving, farming practices. In the cultural field, policy-makers may seek to introduce bilingual policies and incentives to encourage traditional cultural activities, yet it is doubtful whether such affirmative action or cultural engineering produces results comparable with the spontaneous and un-forced development of cultural capital. Just as there is a danger that the environment can be mothballed in ‘nature reserves’, there is also a danger that culture can be mothballed as ‘heritage’, creating artificial islands of tradition in the sea of modernity. The CAP view of rural development, with its strands of competitiveness and safeguards, represents an example of the ‘nature reserve’ ap-proach to cultural diversity. The culture economy approach avoids this, yet the development path for rural areas that emerges is not one which harks back to an era of bucolic under-achievement, and still less one which revives the normativeness and intolerance often associated with many traditional cultures. Rather, it is a path that integrates tradi-tion with the imperatives of the postmodern world in which economic rationality is combined with an appropriate degree of local developmental control.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Garth Hughes for his significant input into an earlier version of this paper, and to the referees of this Journal for their incisive and helpful comments.

References

Appadurai, A., 1981. The past as a scarce resource. Man 16, 201 – 219.

Appadurai, A., Korom, F.J., Mills, M.A. (Eds.), 1991. Gen-der, Genre and Power in South Asian Expressive Tradi-tions. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia. Bassand, M., 1993. Culture and Regions of Europe. Council

of Europe Press, Brussels.

Bauer, P.T., 1984. Remembrance of studies past: retracing first steps. In: Meier, G.M., Seers, D. (Eds.), Pioneers in Devel-opment. Oxford University Press, New York.

Bauman, Z., 1989. Modernity and the Holocaust. Polity Press, Oxford.

Berlin, I., 1980. Against the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas. Hogarth, London.

Bramwell, A., 1989. Ecology in the Twentieth Century: A History. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Carneiro, R., 1968. Cultural adaptation. In: International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 3. Macmillan/Free Press, New York.

Clark, G. (Ed.), 1997. The Impact of Public Institutions on Lagging Rural and Coastal Regions: Final Report to the European Commission (AIR3 CT94 1545). Lancaster Uni-versity, Department of Geography, Lancaster.

Coleman, J., 1968. Modernization. In: International Encyclo-pedia of the Social Sciences, 10. Macmillan/Free Press, New York.

Commission of the European Communities, 1997. Agenda 2000 (DOC/97/6), Strasbourg.

Commission of the European Communities, 1998. Explanatory Memorandum: the Future for European Agriculture (COM (1998) 158 final), Brussels.

Committee of the Regions, 1996. Promoting Local Products: A Trump Card for the Regions (CdR 54/96 fin F/A/G/ht). European Parliament, Brussels.

Cooke, P., Morgan, K., 1993. The network paradigm: new departures in corporate and regional development. Envi-ron. Planning D 11, 543 – 564.

Dasmann, R., 1976. Future primitive. CoEvolution Q. 11, 26 – 31.

Day, G., 1996. Working with the grain. Paper to the World Congress of Rural Sociology, Bucharest.

Durham, W., 1976. The adaptive significance of cultural be-haviour. Hum. Ecol. 4 (2), 89 – 121.

Eliot, T.S., 1948. Notes Towards the Definition of Culture. Faber & Faber, London.

Feyerabend, P., 1987. Farewell to Reason. Verso, London. Firth, R., 1951. Elements of Social Organisation. Watts,

London.

Gans, E., 1985. The End of Culture: Toward a Generative Anthropology. University of California Press, Berkeley. Giddens, A., 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Polity

Press, Cambridge.

Habermas, J., 1987. The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity. Polity Press, Cambridge.

Hagen, E.E., 1980. The Economics of Development, third ed. Irwin, Homewood, IL.

Hamilton, C., 1994. The Mystic Economist. Willow Park Press, Fyshwick.

Hannerz, U., 1990. Cosmopolitans and locals in world culture. In: Featherstone, M. (Ed.), Global Culture: Nationalism, Globalisation and Modernity. Sage, London.

Hannerz, U., 1992. Cultural Complexity: Studies in the Social Organisation of Meaning. Columbia University Press, New York.

Harrison, J., 1927. Themis: A Study of the Social Origins of Greek Religion. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Harvey, D., 1989. The Condition of Postmodernity. Blackwell

(Basil), Oxford.

Hayami, Y., Ruttan, V., 1985. Agricultural Development: An International Perspective (1971). Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD.

Hoselitz, B.F., 1952. Non-economic barriers to economic de-velopment. Econ. Dev. Cultural Change 1, 8 – 21. Hughes, G., Midmore, P., Sherwood, A.M., 1995. The Welsh

Language, Agricultural Change and Sustainability. Rural Economy Research Papers, Aberystwyth.

Iacoponi, I., Brunori, G., Rovai, M., 1995. Endogenous devel-opment and the agroindustrial district. In: van der Ploeg, J.D., van Dijk, G. (Eds.), Beyond Modernization: The Impact of Endogenous Rural Development. Van Gorcum, Assen.

Ilbery, B., Kneafsey, M., 1997. Regional images and the promotion of quality products and services in the lagging regions of the European Union. Paper to the Third Anglo-French Rural Geography Symposium, Nantes.

Ilbery, B., Kneafsey, M. (Eds.), 1999. Regional Images and the Promotion of Quality Products and Services in the Lagging Regions of the European Union: Final Report to the European Commission (FAIR3 CT96 1827). Coventry University, Department of Geography, Coventry. Inglehart, R., 1997. Modernisation and Postmodernisation:

Cultural, Economic and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Ishikawa, S., 1981. Essays on Technology, Employment and Institutions in Economic Development: Comparative Asian Experience. Kinokuniya, Tokyo. Quoted in Ruttan, op.cit.

IUCN, UNEP, WWF, 1991. Caring for the Earth: A Strategy for Sustainable Living. Gland, Switzerland: World Conser-vation Union.

Jacob, F., 1982. The Possible and the Actual. Cape, London. Jenkins, T., 1999. Farm Business Survey in Wales: Statistical Results for 1998/99. Institute of Rural Studies, Aberystwyth.

Jenkins, T., Parrot, N., 1997. Marketing in the context of quality products and services in the lagging regions of the European Union. RIPPLE Working Paper 4. Institute of Rural Studies, Aberystwyth.

Jenkins, T., Parrot, N., 1998. Marketing structures in selected lagging regions of the European Union: an overview. RIP-PLE Working Paper 6. Institute of Rural Studies, Aberystwyth.

Jenkins, T.N., 1998. Economics and the environment: a case of ethical neglect. Ecol. Econ. 26 (2), 151 – 163.

Jones, B., Keating, M. (Eds.), 1995. The EU and the Regions. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Keesing, R., 1981. Cultural Anthropology. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York.

King, F.H., 1933. Farmers of Forty Centuries: Permanent Agriculture in China, Korea and Japan. Cape, London. Kymlicka, W., 1995. The Rights of Minority Cultures. Oxford

University Press, Oxford.

Leopold, A., 1994. A Sand County Almanac (1949). In: Van-DeVeer, D., Pierce, C. (Eds.), The Environmental Ethics and Policy Book. Wadsworth, Belmont, CA.

Marsden, T., Lowe, P., Whatmore, S. (Eds.), 1992. Labour and Locality. David Fulton, London.

Midmore, P., 1998. Rural policy reform and local develop-ment programmes: appropriate evaluation procedures. J. Agric. Econ. 49, 407 – 424.

Milton, K., 1996. Environmentalism and Cultural Theory. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Moran, W., 1993. Rural space as intellectual property. Pol. Geog. 12 (3), 263 – 277.

Murdoch, J., 1995. Actor-networks and the evolution of eco-nomic forms. Environ. Planning A 27, 731 – 757. Norgaard, R., 1994. Development Betrayed. Routledge &

Kegan Paul, London.

Odum, E.P., 1969. The Strategy of Ecosystems Development. Science 164, 260 – 270.

OECD, 1995. Niche Markets as a Rural Development Strat-egy. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Devel-opment, Paris.

Outhwaite, W., 1996. The Habermas Reader. Polity Press, Cambridge.

Pulliam, H.R., Dunford, C., 1980. Programmed to Learn: An Essay on the Evolution of Culture. Columbia University Press, New York.

Putnam, R., 1993. Making Democracy Work. Princeton Uni-versity Press, Princeton, NJ.

Rappaport, R.A., 1971. Nature, culture and ecological anthro-pology. In: Shapiro, H.L. (Ed.), Man, Culture and Society. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ray, C., 1998. Culture, intellectual property and territorial rural development. Sociologia Ruralis 38 (1), 3 – 20. Rushdie, S., 1991. Imaginary Homelands. London.

Ruttan, V., 1988. Cultural endowments and economic devel-opment: what can we learn from anthropology? Econ. Dev. Cultural Change 36, 247 – 271.

Smith, A., 1990. Towards a global culture? Theory Culture Soc. 7, 171 – 192.

Toulmin, S., 1990. Cosmopolis: The Hidden Agenda of Modernity. University of Chicago, Chicago.

Tracy, M., 1989. Government and Agriculture in Western Europe, 1880 – 1988. Harvester, London.

van der Ploeg, J.D., 1992. The reconstitution of locality. In: Marsden, T., Lowe, P., Whatmore, S. (Eds.), Labour and Locality. David Fulton, London.

van der Ploeg, J.D., Saccomandi, V., 1995. On the impact of endogenous development in agriculture. In: van der Ploeg, J.D., van Dijk, G. (Eds.), Beyond Modernization: The Impact of Endogenous Rural Development. Van Gorcum, Assen.

van Dijk, G., van der Ploeg, J.D., 1995. Is there anything beyond modernisation? In: van der Ploeg, J.D., van Dijk, G. (Eds.), Beyond Modernization: The Impact of En-dogenous Rural Development. Van Gorcum, Assen. von Bertalanffy, L., 1962. General Systems Theory: a

Criti-cal Review. General Systems Yearbook.

Waldron, J., 1995. Minority cultures and the cosmo-politan alternative. In: Kymlicka, W. (Ed.), The Rights of Minority Cultures. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Wallerstein, I., 1990. Culture is the world system. In: Feath-erstone, M. (Ed.), Global Culture: Nationalism, Globali-sation and Modernity. Sage, London.

Weber, M., 1976. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1930). Allen & Unwin, London.

Weiss, P., 1971. Hierarchically Organised Systems in Theory and in Practice. Hafner, New York.