A SEMANTIC STUDY ON THE COMPARATIVE AND CONTEXTUAL MEANING OF THE VERB RUN

A Thesis

Presented to The Graduate Program in English Language Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Magister Humaniara (M.Hum) in English Language Studies

by

YOSE RIANUGRAHA Student Number: 086332005

THE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

ii A THESIS

A SEMANTIC STUDY ON THE COMPARATIVE AND

CONTEXTUAL MEANING OF THE VERB RUN

by

Yose Rianugraha Student Number: 086332005

Approved by

Prof. Dr. Soepomo Poedjosoedarmo

_____________________________ _____________________________

iii A THESIS

A SEMANTIC STUDY ON THE COMPARATIVE AND

CONTEXTUAL MEANING OF THE VERB RUN

Presented by

YOSE RIANUGRAHA Student Number: 086332005

Defended before the Board of Examiners and was Declared Acceptable

BOARD OF EXAMINERS

Chairperson : ______________________

Secretary : ______________________

Member : ______________________

Member : ______________________

iv

A PSALM OF DAVID

The LORD is my shepherd, I shall not want;

He makes me lie down in green pastures.

He leads me beside still waters;

He restores my soul.

He leads me in paths of righteousness

for His name’s sake.

Even though I walk through the valley

of the shadow of death,

I fear no evil; for thou art with me;

thy rod and thy staff, they comfort me.

Thou preparest a table before me

in the presence of my enemies;

thou anointest my head with oil,

my cup overflows.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me

all the days of my life;

and I shall dwell in the house of the LORD

for ever…….

STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY

This is to certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of

the thesis writer, and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and

sources have been properly acknowledged. The writer understands the full

consequences, including degree cancellation if he took somebody else’s ideas,

phrases, or sentences without proper references.

Yogyakarta, 7 July 2012

vi

LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN

PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS

Yang bertandatangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma:

Nama : Yose Rianugraha

Nomor mahasiswa : 086332005

demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul:

A SEMANTIC STUDY ON THE COMPARATIVE AND CONTEXTUAL

MEANING OF THE VERB RUN

beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada). Dengan demikian saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma hak untuk menyimpannya, mengalihkannya dalam bentuk media lain, mengelolanya dalam bentuk pangkalan data, mendistribusikannya secara terbatas, dan mempublikasikannya di internet atau media lain untuk kepentingan akademis tanpa perlu meminta ijin dari saya maupun memberikan royalti kepada saya selama tetap mencantumkan nama saya sebagai penulis.

Demikian pernyataan ini yang saya buat dengan sebenarnya.

Dibuat di Yogyakarta pada tanggal 7 Juli 2012

Yang menyatakan

vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, I would like to express my greatest and deepest gratitude

to the Lord, Jesus Christ and Mother Mary, who always stay beside me and have

strengthened me to finish this thesis. It would be impossible for me to finish this

thesis without Their help.

I would like to express my best gratitude to Prof. Dr. Soepomo

Poedjosoedarmo, as my thesis advisor, who has given me guidance, suggestions,

assistance, and support to finish my thesis. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Fr. B. Alip,

M.Pd., M.A., for his help, suggestions and constructive criticisms to my thesis. His

willingness to spend his precious time has been an invaluable contribution to the

accomplishment of this thesis. Also, I would like to thank Drs. FX. Mukarto, M.S.,

Ph.D., Dr. Novita Dewi, M.S., M.A. (Hons), as well as Dr. B. B. Dwijatmoko, M.A.,

for giving me guidance as well as sufficiency of time to finish my thesis. I am

absolutely sure that without their help and attention, I could not have completed this

thesis.

My deepest gratitude also goes to my beloved parents, Imelda Linda Yuniati

and YB. Lian Santoso, as well as my spiritual Father, Pater Martin Suhartono, S.J. I

do really thank them for their affection, continuous prayers, patience and

encouragement during the work on my thesis. Also, I would like to express my

sincere gratitude to my beloved uncle and aunts, Paul Kwa, Yap Liang Nio, Doddy

Liem and Pitoyo families for their prayers, unfailing support, and endless love

viii

My sincere thanks and appreciation go to some people around me. I would

like to thank my undergraduate thesis advisor as well as the head of PBI Department,

Caecilia Tutyandari, S.Pd., M.Pd., who has supported me to finish my thesis. I am

also deeply grateful to my colleagues at KPBB Atmajaya: Suryo Sudiro S.S.,

M.Hum., L. Bening Parwitasukci, M.Hum., Radjaban M.Hum., Paulina Chandra,

M.Hum., and many others for always supporting me to finish my study and being

such nice friends. The next appreciation goes to my colleagues at PPBA Duta Wacana

Christian University: Paulus Widyatmoko, M.A., Andreas Winardi, M.A., Fransisca

Endang Lestariningsih, M.Hum., Fransiskus Ransus, S.S., M.Hum., Bu Ambar, Bu

Nia, and many others for their help and support.

May God always bless all those people abundantly for their kindness.

ix

x

4.2.2 Semantic Properties Related to the verb RUN

as a phrasal verb ... 72

4.2.2.1 Phrasal Verb RUN ACROSS ... 72

4.2.2.2 Phrasal Verb RUN AFTER ... 72

4.2.2.3 Phrasal Verb RUN AROUND ... 76

4.2.2.4 Phrasal Verb RUN AWAY ... 77

4.2.2.5 Phrasal Verb RUN AWAY WITH ... 78

4.2.2.6 Phrasal Verb RUN DOWN ... 79

4.2.2.7 Phrasal Verb RUN IN ... 81

4.2.2.8 Phrasal Verb RUN INTO ... 82

4.2.2.9 Phrasal Verb RUN OFF ... 85

4.2.2.10 Phrasal Verb RUN OFF WITH ... 86

4.2.2.11 Phrasal Verb RUN ON ... 87

4.2.2.12 Phrasal Verb RUN OUT ... 88

4.2.2.13 Phrasal Verb RUN OVER ... 88

4.2.2.14 Phrasal Verb RUN THROUGH ... 90

4.2.2.15 Phrasal Verb RUN TO ... 92

4.2.2.16 Phrasal Verb RUN UP ... 92

4.2.2.17 Phrasal Verb RUN UP AGAINST ... 94

CHAPTER V. CONCLUSION ... 96

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 99

APPENDICES APPENDIX 1: ContrastiveTable between RUN, RACE, GALLOP and SPRINT in conceptual meaning and beyond the conceptual meaning ... 102

APPENDIX 2: Raw Data Table: Semantic Properties Related to the Verb RUN as a Single Verb ... 103

xi

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1 Semantic domain ... 20

Table 2.2 Semantic features ... 28

Table 2.3 Analysis on features related in semantics ... 29

Table 2.4 Contrastive analysis of seven terms involving three types of properties ... 31

Table 2.5 Contrastive analysis of verbs with extended semantic features ... 33

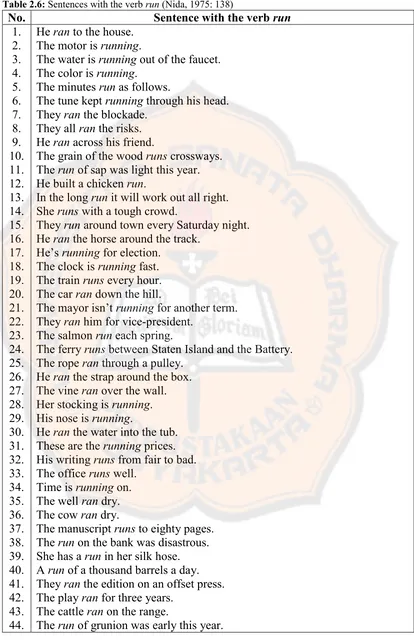

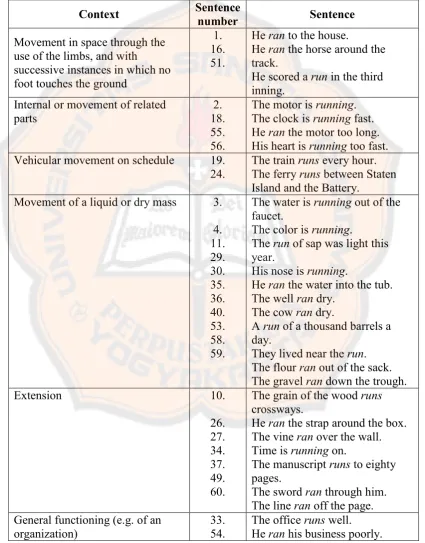

Table 2.6 Sentences with the verb run ... 38

Table 2.7 Groups of sentences within the same context ... 40

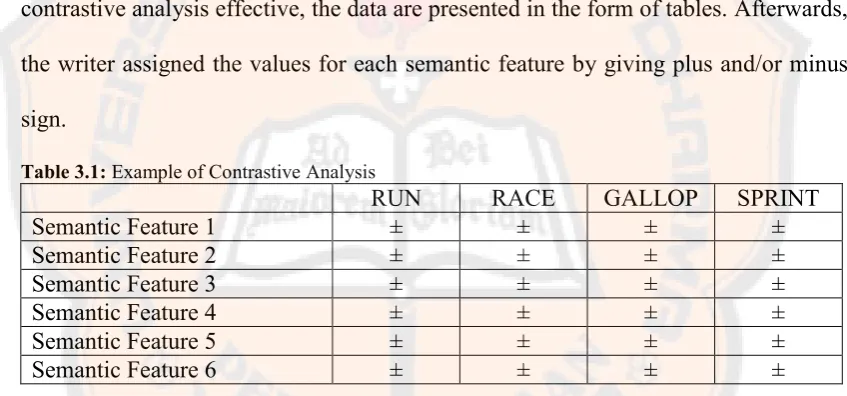

Table 3.1 Example of contrastive analysis ... 48

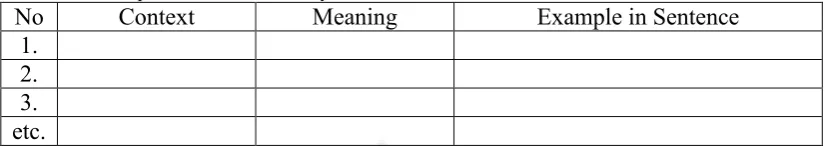

Table 3.2 Example of contextual analysis ... 49

Table 4.1 Comparative Analysis among RUN, RACE, GALLOP, SPRINT ... 52

Table 4.2 Semantic Properties Related to the verb RUN as a Single Verb ... 60

Table 4.3 Comparative Analysis among RUN, RACE, GALLOP, and SPRINT beyond the conceptual meaning ... 71

xii

ABSTRACT

Rianugraha, Yose. 2012. A Semantic Study on the Comparative and Contextual Meaning of the Verb RUN. Yogyakarta: English Language Studies. Graduate Program. Sanata Dharma University.

This study belongs to a semantic study that attempts to examine the meaning of a word scientifically by conducting a comparative analysis. The analysis is carried out by comparing a word with other words which share the same semantic domain. The writer chose the verb run to be analyzed by comparing it with the other verbs in the same semantic domain, i.e. race, gallop, and sprint. The reason why the writer chose this verb is because it has a large number of meanings.

There are two problems to be solved. The first is what are the semantic properties of the conceptual meaning of the verb run when it is compared with the verbs race, gallop and sprint. The second is what semantic properties are related to the conceptual meaning of the verb run when the verb run is put beyond the conceptual meaning. The verb run used by the researcher in this study is run as a single verb and a phrasal verb.

To achieve the objectives, the research employed library or dictionary research for collecting data. The researcher used Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, third edition, published in 2001. First, the writer compared the verb run with other verbs, i.e. race, gallop, and sprint, in order to find the semantic properties between those verbs and assigned the values for each property by

giving ‘plus’ and ‘minus’ sign. To determine the semantic features, the verbs are defined on the conceptual or denotative meaning from the dictionary. After that, the writer searched other meanings beyond the conceptual meaning of the verb run found in the dictionary to determine the context. When the contexts were found and put in sentences, the next step was to find the semantic properties that are related in the comparative analysis.

xiii ABSTRAK

Rianugraha, Yose. 2012. A Semantic Study on the Comparative and Contextual Meaning of the Verb RUN. Yogyakarta: English Language Studies. Graduate Program. Sanata Dharma University.

Penelitian ini merupakan sebuah studi semantik yang bertujuan untuk menganalisa arti sebuah kata secara ilmiah dengan melakukan analisa perbandingan kata. Analisa dilakukan dengan membandingkan sebuah kata dengan kata-kata lain yang masih termasuk dalam satu domain semantik. Penulis memilih kata kerja RUN untuk dianalisa dengan membandingkan dengan kata kerja lain yang memiliki domain semantik yang sama, yaitu RACE, GALLOP dan SPRINT. Alasan mengapa penulis memilih kata ini adalah karena kata kerja RUN memiliki arti yang sangat luas.

Ada dua rumusan masalah dalam penelitian ini. Yang pertama, properti semantik apa saja yang muncul dalam makna konseptual kata kerja RUN, ketika kata kerja tersebut dibandingkan dengan kata kerja RACE, GALLOP dan SPRINT. Yang kedua, properti semantik apa saja yang terkait dengan makna konseptual dari kata kerja RUN ketika kata kerja RUN diterapkan diluar makna konseptual. Kata kerja RUN yang dipakai oleh peneliti adalah sebagai kata kerja tunggal dan kata kerja frase. Dalam prosesnya, penelitian ini menggunakan kamus sebagai sumber utama dalam pengumpulan data. Kamus yang dipergunakan adalah Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English edisi ketiga yang diterbitkan tahun 2001. Pertama-tama, penulis membandingkan kata kerja RUN dengan kata kerja yang lain untuk menemukan properti semantik dan fitur-fitur pembeda diantara kata-kata kerja

tersebut dan memberi nilai dari setiap fitur dengan tanda ‘plus’ dan ‘minus’. Dalam

menentukan fitur-fitur tersebut, kata kerja RUN hanya didefinisikan sebagai makna konseptual atau denotatif menurut kamus. Selanjutnya, penulis mencari beberapa arti dari kata kerja RUN (diluar makna konseptual) dalam kamus untuk menentukan konteks. Ketika konteks tersebut telah ditemukan dan diterapkan dalam suatu kalimat, langkah berikutnya yaitu menemukan properti semantik dan fitur-fitur semantik yang muncul dan terkait dalam analisa pembandingan.

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

In this chapter, the writer will discuss the background of the study, the research questions, the purpose of the study, and the significance of the study.

1.1Background of the Study

Meaning is fundamental to every human society, and language is one of the primary ways of conveying meaning. However, meaning is not a simple

phenomenon. There has been suggestion that meanings are there first, and that language comes later, as a straightforward representation of these prior meanings. Meaning is a kind of ‘invisible, unclothed being’, waiting for the clothes of language

to allow it to be seen. This assumes that meaning and language are in a simple relationship where language reflects some ‘given’ reality.

Nida (1975:11) says that a word seems to have a central meaning from which a number of other meanings are derived. From that point, we then recognize or

imagine some kind of connection between each of these meanings. For instance when we are given the word hand, the first idea that comes up in our mind is part of the body which includes the fingers and the thumb, used to hold things. However, the

word hand now occurs in many kinds of contexts in which it creates diverse meanings, e.g. give a hand, lend a hand, on the other hand, in the hands of somebody,

at first hand, and so on. While meaning is developed, the word hand no longer means

part of the body. Thus, give/lend a hand does not mean to give one’s part of the body

to someone else. It means to help someone with something as in the sentence Can you

2

a hand. Several words may also be developed syntactically. In the same example, the

word hand may also carry out verb part of speech. As in a sentence He handed the

teacher a slip of paper, the word hand means to give something to someone else with

our hand. Even it can mean something else which is not related to part of our body. In a sentence Stories handed down by word of mouth, the word hand means to give or

leave something to people who will live after you.

In our everyday life, we often hear expression like “I seriously mean it.” It

implies that sometimes we say things we do not, in fact, mean. Perhaps it is most often heard coming from frustrated parents who have made too many empty threats to their naughty children. One thing we can find is that speakers of English instinctively

know that there is difference in many cases between what we say and what we mean. In our daily conversation, we use ‘literal’ and ‘non-literal’ meaning to convey our intention. We use the word ‘literally’ to emphasize the honesty and direct

objective of our statements. For example, a mother is talking to her naughty child, “If

you kick Judith one more, I’ll take you straight home and you’ll miss the biscuits!”

The mother finds that she has to emphasize her intention to carry out the message. To illustrate the inferential type of non-literal meaning, we can see from polite requests

made at a dinner-table. If the salt is out of reach from the place we are sitting, we might say, “Is that the salt up your end, Cathy?” This expression occurs as a polite

3

One feature of human language is the fact that it is an ‘arbitrary’ system of

representation. Although not all aspects of meaning in English are completely

arbitrary, it is generally true that there is very little ‘natural’ connection between the words we use and the things they refer to. Language is not the only symbolic system human beings use, although it is probably the most complex one and is used for a

wide variety of purposes. In order to understand the properties of symbolic systems, it is useful for us to know non-linguistic system, such as color symbolism. For example,

the color of green is used as a symbolic color to express ‘go’ in traffic lights, ‘environmentalism’ in the Green Party, or it can also be ‘an open country or parks’

when it refers on maps.

Fromkin (1996:151) states that to understand a language, we need to know the meaning of its words as well as the morphemes that compose them. We must also

know how the meanings of words combine into phrase and sentence meanings. Finally, we must interpret the meaning of utterances in the context in which they are

made. In linguistics, the study of meaning of words, phrases, and sentence is called semantics. Semantics has two subfields, i.e. lexical semantics which is concerned

with the meanings of words and the meaning relationships among words and

sentential semantics which is concerned with the meaning of syntactic unit larger than

the word.

Learning a language includes learning the agreed-upon meanings of certain strings of sounds and learning how to combine these meaningful units into larger units that also convey meaning (Fromkin 1996:152). We are not free to change the

4

communicate with anyone. All speakers of a language share basic vocabulary, the sounds and meanings of morphemes and words. Every dictionary is filled with words

and their meanings and so is the mind of every human being who speaks a language. Our knowledge of meanings permits us to use them to express our thoughts and to understand them when heard. The meaning of words is part of linguistic knowledge

and is, therefore, a part of the grammar. Our mental storehouse of information about words and morphemes is what we have been calling lexicon.

As it is stated before that a word can carry many meanings. Hence, it is worthy to understand the development of words. Resmini (1996) in his article entitled Ambiguitas dan Perubahan Makna says that words might not change in meaning in

short period of time but there is possibility that a word will change over the times. It happens for some lexicons of every language in the world because of several reasons.

First, it happens owing to the development of technology. With the development and invention of advanced technology, there are some changes in meaning or even there

are new words created. For instance, the word mouse used to refer only to a type of animal with a long tail that lives in people’s houses or in fields. Now, as the invention of a computer, the word mouse can refer to a small device which is connected to a

computer, and we can use it by our hand to move cursor or give instruction to the computer. As the internet grows, we can find some new words, such as malware,

phishing, bloggable, or qwerty as they are commonly used in internet nowadays.

The second factor is the development of social and culture. Historical records tell us that interaction between societies and other cultures is not a new phenomenon.

5

a certain purpose of purposes and that language is what the members of a particular society speak. We can see that language in almost any society can take many very

different forms and what forms we should choose to discuss when we attempt to describe the language of a society may prove to be a contentious matter.

Communication among societies is possible because we have knowledge

about language which is shared with others, although how it is shared or even how it is acquired is not well understood. Chomsky (1965), in this case, distinguishes

between what he has called competence and performance. The language we use in everyday living is remarkably varied and when we look closely at any language, we will discover time and time again that there is considerable internal variation, that

speakers make constant use of the many different possibilities offered to them. No one speaks the same way all the time, and people constantly exploit the nuances of

the languages they speak for a wide variety of purposes.

Wardhaugh (1986) highlighted there is a variety of possible relationships

between language and society. One is that social structure may either influence or determine linguistic structure and behavior. Studies show that the varieties of language that speakers use reflect their regional, social or ethnic origin and possibly

even their sex. Other studies show that particular ways of speaking, choices of words and even rules for conversing are determined by certain social requirements.

The relationship between language and culture has fascinated people from a wide variety of backgrounds. When we refer to what we mean by ‘culture’, it does

not refer to the sense of ‘high culture’, i.e. the appreciation of music, literature, arts,

6

consists of whatever it is one has to know or believe in order to operate in a manner acceptable to its members, and to do so in any role that they accept for any one of

themselves. One long-standing claim concerning the relationship between language and culture is that the structure of a language determines the way in which speakers of that language view the world. Thus, the development of society concerning with

social and cultural attitudes, will also provoke the changes in meaning in language. The next factor that brings about changes is the development of the word

usages. Every scientific field usually has vocabulary which is related to that field. For instance, in medical field, there are some particular words which we can only define using specific dictionaries. Given example the term ‘swine influenza’ did not exist

before the nineteenth century. It appears during the outbreak in 2009 in which lots of people died as this viral epidemic spread rapidly. Some medical terms also take Latin

words, as in the word febris, it does not exist in English and we cannot find it in English dictionaries. It comes from Latin which means fever, an abnormally high

body temperature, usually accompanied by shivering, headache, and in severe instances, delirium (Oxford dictionary). It is described in Oxford that the word fever comes from fēfor (Old English) and from febris (Latin), reinforced in Middle English

by Old French fievre, also from febris. Thus, with the invention and development of certain knowledge or fields, it will also bring about changes in lexicons and their

meanings.

Meanings also change due to the perception of our senses. Given the example the word snow, generally it means soft white pieces of frozen water that fall from the

7

different kinds of snow we can define based on our senses. They are flurry, which refers to a small amount of snow that is blown by the wind, flake, which is a feathery

ice crystal, typically displaying delicate sixfold symmetry, graupel, which is small particles of snow with a fragile crust of ice or soft hail, or blizzard, which refers to a severe snowstorm with high winds. We can also define snow based on the shapes of

what we see, i.e. columns to refer to a class of snowflakes that is shaped like a six sided column or one of the 4 classes of snowflakes, dendrites to refer to a class of

snowflakes that has 6 points, making it somewhat star shaped and is the classic snowflake shape, needles to refer to a class of snowflakes that are acicular in shape (their length is much longer than their diameter, like a needle). Based on what we see

or what we feel, new words can be created and improved gradually.

The factor which also brings about changes in meaning of a word is the

association of word. It is an association between a form of speech with something else that is related to that form of speech. For instance, the word drug literally means

a medicine or another substance which has a physiological effect when ingested or otherwise introduced into the body as in the sentence A new drug aimed at sufferers

from Parkinson’s disease. However, when we hear the word drug, sometimes we

associate it with an illegal substance such as marijuana or cocaine, which some people take in order to feel happy, relaxed, or excited.

Ogden and Richards (1985:10-12) maintain that the word, what they called the ‘symbol’, and the actual object, the ‘referent’, are linked only indirectly, by way of

our mental perception of that object, the thought or reference. More recently Ullman

8

sequence of sounds that is the physical form of the utterance, ‘thing’ to denote the

object or event that is being referred to, and ‘sense’ to denote the information that the

name conveys to the hearer.

As mentioned before that learning a language includes learning the agreed-upon meanings of certain strings of sounds and learning how to combine these

meaningful units into larger units that also convey meaning, the writer here would like to conduct a semantic study on the verb run. In our mind, when we hear the word

run, we might refer to an activity of running, i.e. to move our legs more quickly than

when we walk. It is true that run is a kind of activity and thus refers to verb in part of speech. However, in many dictionaries the word run belongs to many different parts

of speech, i.e. noun, verb, adjective and adverb. In addition, every part of speech carries lots of different meaning for the same word. Given the example when the

word run belongs to noun, it has a lot of meanings depending on the context. First, it means ‘a period of time spent running or a distance that you run’, as in the sentence

She usually goes for a run before breakfast. It can mean ‘later in the future or not immediately’, as in the phrase in the long run or in the short run, ‘in the near future’, as in the sentence Sufficient supply, in the short run, will be a problem, ‘a series of

successes or failures’ as in the phrase run of good/bad luck, a run of victories, ‘an amount of a product produced at one time’ as in the phrase a limited run of 200

copies, and so on.

We seldom notice that run may also be an adjective. By adding the suffix – ing, the word run may function as an adjective, as in the phrase the sound of running

9

order, the running order or take a running jump. Likewise, the suffix –ing also makes

the word run change into adverb. Given the example of a sentence She won the prize

for the fourth year running, the word run functions as an adjective which means for

four years, she won the prize constantly.

Nida (1975) says that to determine the linguistic meaning of any form

contrasts must be found, for there is no meaning apart from significant differences. Besides, he also highlights that in endeavoring to determine the meaning of any

lexical unit, from the level of a morpheme to the level of an entire discourse, it is essential to establish the basis of contrast. Thus, the writer here will make a contrastive meaning of the verb run by contrasting with the verbs race, gallop, and

sprint.

To some extent, one word can carry lots of meaning. We can take the example

from the word red which has several meanings, i.e. color or pigment which resembles the hue of blood, emotionally charged terms used to refer to extreme radicals or

revolutionaries, the amount by which the cost of a business exceeds its revenue or a socialist who advocates communism. In order to differ the meaning of a word between one another, we have to put the word into its context. Therefore, the writer

will also conduct the contextual meaning analysis on his study.

1.2Research Questions

10

1. What are the semantic properties of the conceptual meaning of the verb run when it is compared with the verb race, gallop, and sprint?

2. What semantic properties are related to the conceptual meaning of the verb run when it is put beyond the conceptual meaning?

1.3Purpose of the Study

This study is intended to answer two questions. First, it is to examine the meaning of the verb run by comparing it with other verbs in the same semantic

domains, i.e. race, gallop, and sprint. By comparing the verb run with the other verbs, we will find the semantic properties, i.e. properties that appear to provide the comparison and contrast between those verbs, along with the semantic features. After

conducting the comparative analysis, it is important that we should also know the meaning of the verb run beyond the conceptual meaning. By looking up certain

meanings from Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English published by Longman in 2001, we can identify the context of the verb run. From the use of the

verb run in certain contexts, there are some properties that appear and are related to the conceptual meaning. Thus, the second purpose of this study is to find the semantic properties that are related to the conceptual meaning when the verb run is put beyond

the conceptual meaning. So far as what the writer has found, Nida (1975) has provided the contextual meanings of the verb run. Yet, he has not made the

relationship between the semantic properties appeared in contextual analysis and the comparative meaning. In the results and discussion, the writer will present the semantic properties that appear and are related to the conceptual meaning when the

11 1.4Significance of the Study

It is stated that the meaning of a word becomes clear when it is compared with

the other words in the same semantic domain. By comparing the word run with the other verbs in the same semantic domain, we are able to see its difference from semantic features. This study is beneficial as it provides the relationship between the

12

CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter presents review of the related literature. First, it will discuss the

theoretical descriptions, i.e. some descriptions of theories related to this study. After

that, it will present the theoretical framework, i.e. the theories discussed in the

descriptions used by the writer in this study.

2.1Theoretical Descriptions

In the theoretical descriptions, the writer would like to review some theories

related to his study, i.e. theories of meaning, word meaning, types of meaning,

semantic domain, semantic features, contrastive meaning, and contextual meaning.

2.1.1. Theories of Meaning

Meaning is a central and fundamental concept to the whole study of language.

However, as Ullmann (1964: 54) points out, it is also “one of the most ambiguous and

most controversial terms in the theory of language.” Kempson (1977: 11) agrees with

this statement when asserting that the problem of what we mean when we refer to the

meaning of a word or a sentence “is the classical problem of semantics, the problem

indeed on which semantics has traditionally foundered.” She also mentions three

main ways in which linguists and philosophers have attempted to construct

explanations of meaning in natural language (1977: 11), i.e. by defining the nature of

word meaning, defining the nature of sentence meaning, and explaining the process of

communication.

For over decades, linguists have spent a large amount of time finding out the

13

Richards (1923) has found twenty-two definitions of meaning. Some of the

definitions of meaning are: an intrinsic property; the other words annexed to a word

in the dictionary; the connotation of a word; an essence; that to which is actually

related to a sign by a chosen relation; that to which the user of a symbol actually

refers, etc. They show how confusion and misunderstanding arise because of lack of

agreement on such a basic term (1946: 186-187).

Bloomfield (1933) has had a slightly different emphasis on meaning. It was

not the scientific study of mental phenomena, i.e. thought and symbolization, but the

scientific definition of everything to which language may refer.

We can define the meaning of a speech-form accurately when this meaning has to do with some matter of which we possess scientific knowledge. We can define the names of minerals, for example, in terms of chemistry and mineralogy, as when we say that the ordinary meaning of the English word salt is ‘sodium chloride’ (NaCl), and we

can define the names of plants or animals by means of the technical terms of botany or zoology, but we have no precise way of defining words like love or hate, which concern situations that have not been accurately classified – and these latter are in the great majority. (Language, p. 139)

Finally, Bloomfield has come to a conclusion that the definition of meaning

progresses by a continuing process of revision and clarification, leading to greater

clarity and depth of understanding.

2.1.2. Word Meaning

The definition of word meaning is as elusive as the definition of the term

meaning. Ogden and Richards (1946: 10) claim that the words mean nothing by

themselves and it is only when a thinker makes use of them that they stand for

anything, or, in one sense, have „meaning‟. It is a consequence of their theory of

meaning presented by the semiotic triangle where the relationship between symbol

14

indirectly, through the thoughts of people who use them and therefore the meaning of

a word may vary slightly in the conceptual schemata of individual speakers, and the

way in which the world is conceived may also vary from speaker to speaker.

Crystal (1985: 236) adds that the assumption that words carry the meaning in

a language is wrong as the meaning is carried by sentences. In order to understand

what is meant, we have to put the word in a context, which usually means to put it

into a sentence (e.g. the word „table‟ which can mean either a piece of furniture or a

part of a printed page).

Taylor (2003:87) explicitly says that we can only understand the meaning of a

linguistic form in context of other cognitive structures and he stresses the fact that

word meanings are always characterized against a particular context, e.g. the word

Monday in the context of the concept „week‟. Cruse (1986: 16) also insists on the

importance of context when claiming that the meaning of a word is constituted by its

contextual relations. Hofmann then avoids the idea that a word has a fixed meaning

that you can look up in the dictionary (1993: 9) and claims that word meanings

cannot be true or false until applied to something (1993: 15).

The meaning of a word cannot be possibly defined because it can vary in the

minds of different speakers; in addition, the meaning always depends on the context.

Hence, the meaning of the words always depends on their relation to other words as

well as on the whole context. This is even more true about the evaluative words such

as the selected adjectives pretty and handsome. The meaning of the adjectives

depends on the object they collocate with (e.g. living or non-living beings) as well as

15

2.1.3. Types of Meaning

Leech (1981) acknowledges three main points about the study of meaning.

The first is that it is mistaken to try to define meaning by reducing it to the terms of

sciences other than the science of language, e.g. to the terms of psychology or

chemistry. The second is that meaning can best be studied as a linguistic phenomenon

in its own right, not as something „outside language‟. This means we investigate what

it is to „know a language‟ semantically, e.g. to know what is involved in recognizing

relations of meaning between sentences, and in recognizing which sentences are

meaningful and which are not. The last is that he points the distinction between

„knowledge of language‟ and „knowledge of the real world‟.

Leech (1981) presents seven Types of Meaning, i.e. conceptual meaning,

which deals with semantic competence; connotative meaning; social meaning;

affective meaning; reflected meaning; collocative meaning; and thematic meaning.

Conceptual meaning is sometimes also called denotative or cognitive meaning

and is widely assumed to be the central factor in linguistic communication. There are

two structural principles that seem to lie at the basis of all linguistic patterning, i.e.

the principle of contrastiveness and the principle of structure. In contrastive features,

the conceptual meanings of a language can be studied by assigning the positive sign

[+] to the feature it possesses and also by assigning the negative sign [-] to the feature

it does not possess. For example, the meaning of the word woman can be specified as

[+ human], [- male], and [+ adult]. The second principle, that of structure, is the

principle by which larger linguistic units are built up out of smaller units, by which

16

its immediate constituents through a hierarchy of sub-division to its ultimate

constituents or smallest syntactic elements. For example, a sentence No man is an

island can be represented by bracketing: {(No)(man)}{[(is)][(an)(island)]}. The two

principles of contrastiveness and constituent structure represent the way language is

organized respectively on what linguists have termed the paradigmatic and

syntagmatic axes of linguistic structure.

Connotative meaning is the communicative value an expression has by virtue

of what it refers to, over and above its purely conceptual content. To some extent, the

notion of „reference‟ overlaps with conceptual meaning. In conceptual meaning, the

word woman is defined as [+ human], [- male], and [+ adult]. But, there is

non-criterial properties that we can learn to expect a referent of woman to possess. They

include not only physical characteristics, e.g. biped, having a womb, but also

psychological and social properties, e.g. gregarious, subject to maternal instinct, and

may extend to features which are merely typical rather than invariable concomitants

of woman-hood, e.g. capable of speech, experienced in cookery,

skirt-or-dress-wearing.

Social meaning refers to a piece of language that conveys the social

circumstances of its use. We recognize some words as being dialectical, i.e. telling us

something of the geographical or social origin of the speaker. Other features of

language tell us something of the social relationship between the speaker and hearer.

In a more local sense, social meaning can include what has been called the

„illocutionary force‟ of an utterance, e.g. whether it is to be interpreted as a request,

17

example, has the form and meaning of an assertion, and in social reality (e.g. if it is

said to the waiter in a restaurant) it can readily take on the force of a request such as

Please bring me a knife.

Affective meaning is often explicitly conveyed through the conceptual or

connotative content of the words used. It is largely a parasitic category in the sense

that to express our emotions we rely upon the mediation of other categories of

meaning – conceptual, connotative, or stylistic. Emotional expression through style

comes about, e.g. when we adopt an impolite tone to express displeasure when we ask

someone to be quiet (such as Will you belt up!) or when we adopt a formal tone to

express politeness (such as I’m terribly sorry to interrupt, but I wonder if you would

be so kind as to lower your voices a little). Thus, factors such as intonation and tone

of voice are also important here. On the other hand, there are elements of language,

e.g. interjections like Aha!, that the primary function is to express emotion. When we

use these, we communicate feelings and attitudes without the mediation of any other

kind of semantic function.

Reflected meaning is the meaning which arises in cases of multiple conceptual

meaning, i.e. when one sense of a word forms part of our response to another sense.

For example, in a church service the synonymous expressions The Comforter and The

Holy Spirit, both referring to the Third Person of the Trinity. The Comforter sounds

warm and „comforting‟, while The Holy Spirit sounds awesome.

Collocative meaning consists of the associations a word acquires on account

of the meanings of words which tend to occur in its environment. For example, the

18

but may be distinguished by the range of nouns with which they are likely to co-occur

or collocate. We usually use the word pretty followed by girl or woman and we use

the word handsome followed by boy or man.

Thematic meaning refers to what is communicated by the way in which a

speaker or writer organizes the message, in terms of ordering, focus, and emphasis.

For example, it is often felt that an active sentence such as Mr. Brown donated the

first prize has a different meaning from its passive equivalent The first prize was

donated by Mr. Brown, although in conceptual content they seem to be the same.

These two sentences have different communicative values in that they suggest

different contexts: the active sentence seems to answer an implicit question What did

Mr. Brown donate? While the passive sentence seems to answer an implicit question

Who was the first prize donated by? or Who donated the first prize?.

2.1.4. Semantic Domain

According to Nida (1975), distinctions in meaning are best described in

terms of the semantic domains to which they belong. It is essential that an extensive

analysis and description of domains be provided, in order that their nature and

function may be understood. A semantic domain consists essentially of a group of

meanings which share certain semantic components. The features of domains can be

best described in terms of size, hierarchical levels, multiple memberships,

archilexemes, or boundaries.

Nida has found that the largest single domain in any language consists of

four items. The first is entities or objects, which can be classified into countable, e.g.

19

etc. The second is events, which can be classified into actions and processes, e.g.

rain, come, run, go, hit, speak, grow, enlarge, widen, diminish, etc. The third is

abstracts, which consist of qualities, e.g. good, bad, beautiful, ugly, etc., quantities,

e.g. much, few, many, little, etc., and degrees, e.g. very, too, so, etc. The fourth is

relationals, which primarily mark the relations between objects, events, and abstracts,

are a somewhat smaller class, e.g. in, beside, through, around, with, and, or, but,

when, although, nevertheless, etc.

Nida has found an interesting aspect of these four principal semantic

domains, that is they appear to be universals and that these sets of meanings are tied

in all languages to corresponding grammatical classes: nouns, verbs,

adjectives-adverbs, and preposition-conjunctions. For the semantic domain which consists of

four items, Nida referred to a Greek dictionary to present all of them. The table of

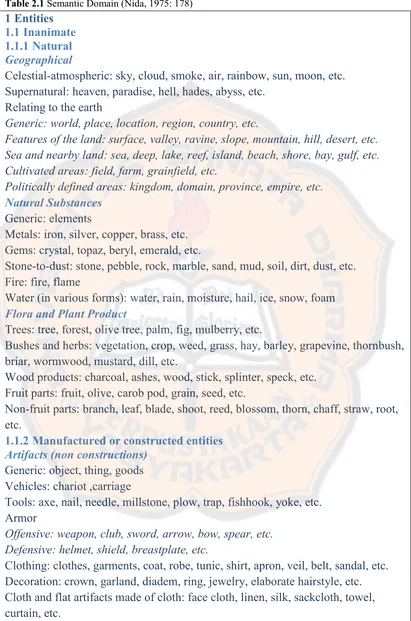

semantic domain can be shown in table 2.1.

2.1.5. Semantic Features

Another approach to the description of word meanings is semantic features.

The concept of features was firstly developed by the Prague School of linguistic

around 1940 for phonology within a so-called functional approach (Lipka, 2012:

124). Later on, Chomsky (1965) took over the concept of features from phonology

and introduced complex symbols as sets of „syntactic features‟ (Lipka, 1986: 87).

Hjelmslev, one of the founders of structural semantics, found out that there parallels

between phonological and semantic levels of languages. Then, the concepts of

features were transferred to the study of semantics by generative grammarians

20

Table 2.1 Semantic Domain (Nida, 1975: 178)

1Entities

1.1Inanimate 1.1.1Natural Geographical

Celestial-atmospheric: sky, cloud, smoke, air, rainbow, sun, moon, etc. Supernatural: heaven, paradise, hell, hades, abyss, etc.

Relating to the earth

Generic: world, place, location, region, country, etc.

Features of the land: surface, valley, ravine, slope, mountain, hill, desert, etc. Sea and nearby land: sea, deep, lake, reef, island, beach, shore, bay, gulf, etc. Cultivated areas: field, farm, grainfield, etc.

Politically defined areas: kingdom, domain, province, empire, etc. Natural Substances

Generic: elements

Metals: iron, silver, copper, brass, etc. Gems: crystal, topaz, beryl, emerald, etc.

Stone-to-dust: stone, pebble, rock, marble, sand, mud, soil, dirt, dust, etc. Fire: fire, flame

Water (in various forms): water, rain, moisture, hail, ice, snow, foam Flora and Plant Product

Trees: tree, forest, olive tree, palm, fig, mulberry, etc.

Bushes and herbs: vegetation, crop, weed, grass, hay, barley, grapevine, thornbush, briar, wormwood, mustard, dill, etc.

Wood products: charcoal, ashes, wood, stick, splinter, speck, etc. Fruit parts: fruit, olive, carob pod, grain, seed, etc.

Non-fruit parts: branch, leaf, blade, shoot, reed, blossom, thorn, chaff, straw, root, etc.

1.1.2Manufactured or constructed entities Artifacts (non constructions)

Generic: object, thing, goods Vehicles: chariot ,carriage

Tools: axe, nail, needle, millstone, plow, trap, fishhook, yoke, etc. Armor

Offensive: weapon, club, sword, arrow, bow, spear, etc. Defensive: helmet, shield, breastplate, etc.

Clothing: clothes, garments, coat, robe, tunic, shirt, apron, veil, belt, sandal, etc. Decoration: crown, garland, diadem, ring, jewelry, elaborate hairstyle, etc. Cloth and flat artifacts made of cloth: face cloth, linen, silk, sackcloth, towel, curtain, etc.

21

Lighting and lampstands: lantern, torch, lamp, lampstand, etc.

Containers: vessel, dish, water jar, jug, pitcher, purse, wineskin, manger, feeding trough, winepress, sponge, etc.

Coins: money, copper coin, gold coin, assarion, denarius, talent, etc. Idols and images: statue, idol, image, cherubim, etc.

Musical instruments: gong, cymbal, harp, flute, trumpet, etc.

Objects involved in written communication: paper, parchment, tablet, scroll, pen, ink, seal, etc.

Objects involved in binding: rope, chain, stocks, bonds, etc. Objects involved in execution: cross

Processed substances

Generic: food, meal, nourishment, drink, scraps, crumbs, etc.

Vegetable products: bread, fruit, grain, flour, olive oil, fig, grapes, wine, yeast, manna, etc.

Animal products: meat, milk, fish, egg, honey, etc. Condiments: salt, cinnamon, spice, etc.

Poisons: deadly poison, magic potion, poison Medicine: eye salve, ointment

Perfumes: oil of nard, aloes, incense, perfume, frankincense, myrrh, etc. Constructions

Large non-dwellings: building, temple, sanctuary, tabernacle, synagogue, palace, camp, fortress, tower, barn, jail, prison, etc.

Dwellings: inn, tavern, house, home, tent, etc.

Open constructions: fold, market, theatre, stadium, court, etc.

Parts of buildings: room, bedroom, banquet hall, stable, gate, door, porch, wall, flight of steps, window, etc.

Small non-dwellings: grave, tomb, oven, furnace, mill, fence, etc. Building materials: keystone, board, plank, beam, pillar, tile, etc. Excavations: cellar, pool, well, pit, ditch, etc.

Places of business: bank, tax office, judicial bench, etc.

Ships and parts of ships: vessel, sailing vessel, ship, boat, stern, bow, sail, tackle, anchor, rudder, etc.

1.2Animate

1.2.1Animals, birds, insects

Generic: living thing, animal, beast, four-footed animal

Birds: bird, sparrow, crow, raven, eagle, vulture, dove, pigeon, etc. Insects: locust, grasshopper, moth, gnat, mosquito, etc.

Animals

Wild: beast, bear, wolf, fox, lion, leopard, dragon, etc.

22

hog, swine, sow, calf, ox, bull, colt, donkey, goat, lamb, horse, camel, dog, flocks, herds, team, yoke, etc.

Animal body parts and products: wing, tail, wool, horn, etc. 1.2.2Human beings

Generic and distinctions by age and sex

Generic: man, human nature, mankind, people, person, etc. Males: man, old man, young man, girl, etc.

Females: woman, old woman, young woman, girl, etc. Children: baby, infant, child, etc.

Kinship

Generic: generation, relatives, family, genealogy, tribe, race, etc.

Offspring: descendants, posterity, son, daughter, firstborn, grandchild, orphan, etc. Parents and forefathers: patriarch, fore-father, ancestor, parent, father, mother, grandmother, etc.

Affinals: husband, wife, father-in-law, bridegroom, bride, etc. Collaterals: foster brother, brother, sister, cousin, etc.

Groups

Socioreligious: congregation, church, outsiders, brotherhood, Gentile, pagan, party, sect, proselyte, synagogue, etc.

Sociopolitical: assembly, state, nation, citizen, alien, foreigner, exile, etc. Religiopolitical: body of elders, Sanhedrin, local council, etc.

Social: household, companion, friend, comrade, neighbor, etc. Body, body parts, and body products

Generic: body, corpse

Parts: member, head, skull, forehead, eye, ear, nose, mouth, tongue, tooth, neck, breast, womb, stomach, leg. knee, thigh, etc.

Body products: vomit, clot of blood, saliva, gall, tear, sweat, etc. 1.2.3Supernatural powers or beings

Powers of personifications: heavenly being, stars (army) of heaven, spirit of divination, elemental spirits, Justice, Aeon, etc.

Personal beings: god, goddess, demon, evil spirit, angel, archangel, ghost, apparition, etc.

2.1.4burning: burn, smoke, extinguish, smoulder, etc.

2.2Physiological

2.2.1eating: nurse, devour, dine

2.2.2reproduction: copulate, become pregnant, give birth, miscarriage

23

2.2.4die: die, lay down one's life, be at death's door, drown

2.3Sensory

2.3.1hearing: hear, listen to, overhear

2.3.2touch: touch, feel, tap

2.3.3see: see, regain one's sight, observe, watch closely, be an eyewitness

2.3.4taste: taste

2.3.5smell: smell

2.4Emotive

2.4.1desire for: love, desire, passion

2.4.2opposition to: hate, despise, be jealous of

2.4.3fear-anxiety: fear, be anxious about, worry

2.4.4sadness: mourn, sorrow, sad

2.5Intellectual

2.5.1thinking: reason, plan, calculate, imagine

2.5.2memory: remember, forget, recall

2.5.3decision: judge, decide, select, compare

2.5.4perceiving and learning: recognize, discover, learn

2.6Communication

2.6.1non-verbal: signal, make a sign, wail, laugh

2.6.2speaking: speak, talk, shout

2.6.3writing-reading: write, sign, read

2.6.4religious: pray, prophesy, oath

2.6.5instruction: teach, explain, admonish, persuade, instruct

2.6.6dialogue: argue, converse, debate

2.6.7command: order, command, demand

2.7Association

2.7.1coming together: associate, unite, meet, join

2.7.2opposition to: rebel, fight, war, oppose

2.7.3marriage: betroth, marry, divorce

2.7.4hospitality: visit, receive as guest, wash the feet of

2.7.5appropriate interpersonal: make a covenant with, be loyal to, be merciful to, respect, honor

2.8Control

2.8.1put under control: conquer, overcome, seize, arrest, catch

2.8.2rule over: rule, direct, keep watch over, govern, make obey

2.8.3resistance to control: disobedience, disobey, refuse, escape

2.8.4punishment: correct, punish, discipline

2.9Movement

2.9.1general: move, travel, roam, wander

2.9.2directionally oriented movement: come, go, encircle, arrive, leave, return, enter

2.9.3means of movement: walk, run, jump, leap

2.9.4medium of movement: fly, swim

2.9.5association: lead, bring, follow, accompany

2.10Impact

24

2.10.2crush-smash: crush, shatter, smash into pieces

2.10.3cut-stab: cut, hew, shear, wound, pierce, sting

2.10.4beat: beat, strike, hit, slap, knock down

2.10.5kill: kill, murder, slay, stone, choke, behead

2.10.6ruin-destroy: ruin, destroy, abolish, demolish, lay waste

2.10.7harm-injure: harm, injure, inflict, wound

2.11Transfer

2.11.1distribution: distribute, give, divide among, waste

2.11.2receiving: take, receive, accept, acquire, gain

2.11.3transfer of assets: deposit with, invest, entrust to

2.11.4transfer by force: plunder, steal, rob

2.11.5commercial transactions, often reciprocal: buy/sell, borrow/lend, pledge/redeem, exchange

2.12Complex activities

2.12.1agricultural: sow, plow, harvest

2.12.2involving domesticated animals: herd, care for, shear

2.12.3food processing: cook, prepare a meal

2.12.4involving cloth: spinning, weaving, sewing

2.12.5involving constructions: build, erect, tear down

2.12.6religious rites: sacrifice, worship, circumcision, celebrating the Passover

3Abstracts

3.1Time: today, tomorrow, future, year

3.2Distance: Sabbath day's journey, stadion, cubit

3.3Volume: ephah, kor

3.4Velocity: slow, fast, quickly

3.5Temperature: hot, cold, lukewarm

3.6Color: black, purple, scarlet, white

3.7Number: one, two, three

3.8Status: rich, poor, slave, free

3.9Religious character: holy, profane, clean, unclean, godless, devout

3.10Attractiveness: attractive, beautiful, ugly

3.11Age: old, young, ancient, new

3.12Truth-falsehood: true, false, honest, deceitful

3.13Good-bad: good, bad, right, wrong, righteous, unrighteous

3.14Capacity: able, unable, capable, incapable, strong, weak

3.15State of health: well, sick, strong, weak

4Relationals

4.1Spatial: up, down, around, before, behind, through

4.2Temporal: when, while, during, since

4.3Deictic: this, that, former, latter, the, a

25

Jackson (1988) defines semantic features as a subclass of semantic

components, which serve to identify a semantic domain and then help to distinguish

lexemes from each other within this domain. Many linguists, such as Leech, use the

terms semantic features and semantic components interchangeably as synonyms.

Lipka (1980) did not distinguish these two terms either, but in his recent book he

begins using the term „feature‟ for a subclass of components (Lipka, 2002: 126).

Lipka also argues that semantic features as metalinguistic elements can be

derived in two ways. The first is by purely language-immanent procedures from the

opposition of lexical items, or the second is from properties or attributes of the

extralinguistic referent or denotatum in a referential approach semantics. He then

classifies semantic features into seven different types.

The first semantic feature is „denotative features‟. According to Lipka (2002),

denotative features are based on cognitive features, properties, or attributes of the

extralinguistic denotatum and may be derived by purely language immanent

procedures on the basis of acceptable paraphrases. Based on this argument, he states

that denotative features are the most important and central features of a lexeme. The

reason of this is that denotative features are inherent, i.e. always obligatory present or

absent. An example of a denotative feature is [± HUMAN] in girl vs. filly. HUMAN

here is a property of the referent of the word girl. Lipka‟s denotative features

correspond to Leech‟s conceptual or denotative meaning and Lyons‟s descriptive

meaning.

The second type is „connotative features‟. Lipka (2002) formulates the

26

needed to capture differences between the words steed and horse or to smile and to

strike. English dictionaries use labels such as „archaic, literary, humorous‟ for

connotative features (Lipka, 2002: 127). Lipka claims that connotative features are

inherent components of a lexeme and do not concern properties of the denotatum. In

other words, connotative features are properties of a lexeme. Krisnawati (2003)

formulates connotative features as additional features that the speaker or hearer

catches when he hears or reads a pair of lexemes in terms of lexemes themselves.

The third type is „relational features‟. Some lexemes that involve relations, for

example, father and son, according to Lipka, cannot be explained with the help of

properties or binary contrast. Such lexemes require different explanations. He

proposes relational features as a way to analyze converses or relational lexemes.

Thus, the relational father of is symbolized by [→ PARENT] and son of by the

feature notation [← PARENT] (Lipka, 2002: 128). In writing this feature, Lipka

adopted the notational convention of arrows from Leech.

The fourth type is „transfer features‟. Transfer features are fundamentally

syntagmatic in nature (Lipka, 2002: 18). Taking Weinrich‟s example, Lipka explains

the representation of the sentence He was drinking carrot with transfer features:

[+SOLID] → < − SOLID>. The feature < − SOLID> is transferred from the verb

drink to its grammatical objects carrots. There it replaces the contradictory inherent

feature [+ SOLID]. As a result of the transfer process, carrots will be interpreted as

carrot juice. The angular bracket, < >, used in this feature are adopted by Lipka from

Weinrich. He further notes that transfer features are also needed for explaining

27

The fifth type is „deictic features‟. Lipka notes that deictic features are used to

explain certain locative, temporal relations and direction. For example the feature

[± PROXIMATE] symbolizes proximity to the speaker for lexemes now vs. then, or

come vs. go.

The sixth type is „inferential features‟. According to Lipka, inferential features

(IFs) do not occur in traditional semantics. From a synchronic point of view, as he

sees it, only variable IFs can explain fuzziness in meaning, polysemy, regional,

stylistic, and other variations. On the diachronic scale, they capture semantic

restriction, extension, shift and other changes in meaning. According to Lipka, IFs

may be used for formalizing the properties of a referent or denotatum and may occur

in paraphrases, e.g. feature {STICK} to explain the word to beat and feature {TO

GET ATTENTION} to the word to nudge. The braces used in this notation of IFs are

taken from Lehrer (Lipka, 2002: 126).

The seventh type is „distinctive features‟. Distinctive features are a super-class

of features discussed in points 1-5 above. Lipka defines distinctive feature as all

semantic features that serve to distinguish a pair of lexemes that are otherwise

identical in meaning. Thus for example cat and kitten are only distinguished by

denotative feature [± ADULT], or steed and horse by the connotative feature

[+ARCHAIC].

2.1.6. Contrastive Meaning

Lexicon is the part of the grammar that contains the knowledge speakers have

about individual words and morphemes, including semantic properties. Fromkin et al.

28

class, e.g. the semantic class of „female‟ words. Semantic classes may intersect, such

as the class of words with the properties „female‟ and „young‟. In some cases,

however, the presence of one semantic property can be inferred from the presence or

absence of another. For example, words with the property „human‟ also have the

property „animate‟, and lack the property „equine‟.

One way of representing semantic properties is through the use of semantic

features. Semantic features are a formal or notational device for expressing the

presence or absence of semantic properties by pluses and minuses. For example, the

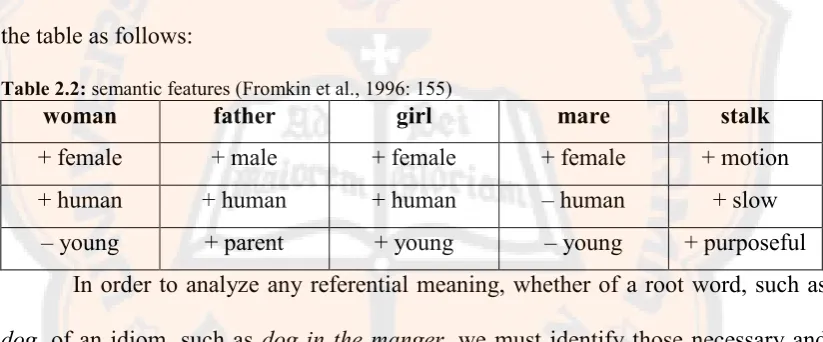

lexical entries for words such as woman, father, girl, mare, and stalk would appear in

the table as follows:

Table 2.2: semantic features (Fromkin et al., 1996: 155)

woman father girl mare stalk

+ female + male + female + female + motion

+ human + human + human – human + slow

– young + parent + young – young + purposeful

In order to analyze any referential meaning, whether of a root word, such as

dog, of an idiom, such as dog in the manger, we must identify those necessary and

sufficient features that distinguish the meaning of any one form from every other

from which might compete for a place within the same semantic territory. It is

necessary also to find out what the relations are between the components, since that

also is crucial for the understanding of meaning.

To determine the meaning of any lexical unit, from the level of a morpheme to

the level of an entire discourse, it is essential to establish the basis of contrast. To do

so effectively, those units most closely related semantically must be identified, that is

29

from one another in the smallest number of diagnostic components. Such meanings

should be on the same hierarchical level, since on this basis they are likely to share

the greatest number of common components, while differing most clearly with

respect to crucial contrasts. The analysis is then called a contrastive meaning analysis.

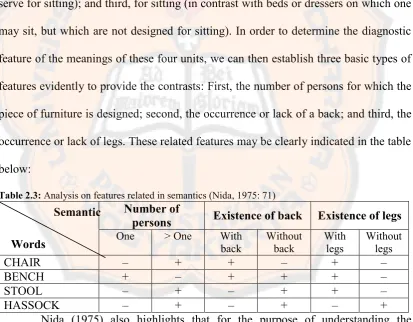

One simple example to illustrate the analysis is the set of words chair, stool,

bench, and hassock. Four of them obviously share a number of common components:

First, artifacts (in contrast with stone ledges on which one might sit); second, pieces

of furniture (in contrast with other constructions, e.g. banks or sawhorses which can

serve for sitting); and third, for sitting (in contrast with beds or dressers on which one

may sit, but which are not designed for sitting). In order to determine the diagnostic

feature of the meanings of these four units, we can then establish three basic types of

features evidently to provide the contrasts: First, the number of persons for which the

piece of furniture is designed; second, the occurrence or lack of a back; and third, the

occurrence or lack of legs. These related features may be clearly indicated in the table

below:

Table 2.3: Analysis on features related in semantics (Nida, 1975: 71) Number of

persons Existence of back Existence of legs

One > One With

possible variety of components and the relations of sets of meanings to one another,

one of the most useful series consists of meanings involving physical movement

through space. He begins with a related set of meanings represented by the terms run,

Words

30

walk, hop, skip, jump, crawl, and dance. It is important as to insure not being

confronted at first with a number of variables, e.g. the hopping of toads, the dancing

of trained bears, and the crawling of cars through traffic.

Although we already know that what appears to be an obvious contrast

between run and walk is relative speed, the important diagnostic feature is the nature

of the contact between the feet and the supporting surface. In run, hop, skip, jump,

and some uses of dance, there are moments when neither foot is touching the ground.

Whereas crawl, walk, and other uses of dance, at least one foot is always in contact

with the ground. Another contrast in this set of meanings is the distinction between

crawl, which needs four limbs to perform, and the other meanings, which need only

two. Yet, the most specific set of contrasts involves the order of movement of the

feet. For walk and run the order of contact with the ground is alternating 1–2–1–2–1–

2; for hop the order is 1–1–1–1 or 2–2–2–2; for skip the order is 1–1–2–2–1–1–2–2;

and crawl the order is usually 1–3–2–4–1–3–2–4, if the limbs are numbered

clockwise, but there are several different possible orders. Number one represents the

right leg, number two represents the left leg, number three represents the left arm, and

number four represents the right arm. For dance the order of contact with the ground

varies greatly, but one distinguishing feature is that it is rhythmic, while for jump the

order of contact at the beginning or end of the jump is irrelevant. What counts is the

relatively greater distance involved in which there is no contact with the surface.

Nida found that the contrasts in meaning of these seven terms involve only

three major types of features, namely the type of contact with the surface, the order of