B

RIEF

R

EPORT

Long-Term Adaptive Life Functioning in Relation to

Initiation of Treatment with Antipsychotics over the

Lifetime Trajectory of Schizophrenia

John Quinn, Maria Moran, Abbie Lane, Anthony Kinsella, and John L. Waddington

Background: There is evidence that the stage of illness at

which antipsychotic treatment is initiated in schizophrenia may have consequences for its subsequent course. How this might relate to impaired adaptive life functioning in the long-term is poorly understood.

Methods: Thirty-eight inpatients, many of whom had been

admitted in the preneuroleptic era, were assessed using the Social-Adaptive Functioning Evaluation (SAFE); con-stituent clinical and medication phases of the lifetime trajectory of their illnesses were then analyzed to identify predictors of SAFE score using multiple regression modeling.

Results: The primary, independent predictor of SAFE

score was duration of initially unmedicated psychosis, which accounted for 22% of variance (p,.001) therein. Conversely, duration of subsequently treated illness, al-though decades longer, failed to predict SAFE score.

Conclusions: These findings are consistent with some

form of “progressive” process, particularly over the first several years following the emergence of psychosis, which is associated with accrual of deficits in adaptive life functioning. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:163–166 © 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry

Key Words: Schizophrenia, adaptive life functioning, initially unmedicated psychosis, long-term outcome

Introduction

T

hat outcome in schizophrenia might be influenced by the stage of illness at which treatment with antipsychotics was initiated is attracting renewed atten-tion. One proposition (Birchwood et al 1997; McGlas-han and JoMcGlas-hannessen 1996; Wyatt 1991) is that delayed intervention with antipsychotics may be associated with poorer outcome. For example, in first-episode studies,increasing duration of untreated psychosis appears to be associated with a longer time to remission, poorer quality of remission, and increasing likelihood of sub-sequent relapse (Loebel et al 1992; Szymanski et al 1996). Our alternative approach has been to study a naturalistic circumstance that has resulted in patients who have experienced prolonged periods of initially unmedicated psychosis and in whom correlates thereof might be most prominent. Specifically, we have studied older patients who became ill in the preneuroleptic era and therefore endured many years of illness before antipsychotics were introduced.

In an initial study of this type, increasing duration of initially unmedicated psychosis appeared to be associ-ated with increasing severity both of negative (but not positive) symptoms and of general (but not executive) cognitive impairment (Scully et al 1997b). Nonetheless, the nature of such associations within the overall lifetime trajectory of schizophrenia (Waddington et al 1998, 1999) and, in particular, any impact in terms of long-term outcome at a functional level, are poorly understood. In our study, we evaluated such patients for adaptive life functioning and, as an anchor to our previous study, for general and executive cognitive function. In addition, we resolved the patients’ lifetime illness trajectory in a novel manner into its sequential phases: from birth to onset of psychosis, through initiation of antipsychotics, to subsequently medicated illness in terms of both the duration of antipsychotic treatment and of interpolated drug-free intervals, and to index assessments at their current age. Some explor-atory studies of craniofacial dysmorphogenesis, a puta-tive index of early neurodevelopmental adversity (Lane et al 1997; Waddington et al 1999) and of neurological soft signs as an additional index of such compromised brain function (Lane et al 1996; Waddington et al 1998) also were made. Thereafter, we have applied multiple regression modeling to identify which phase(s) of illness might independently predict functional outcome measures; a particular hypothesis to be tested was that increasingly delayed intervention with antipsychotics would be a primary predictor of poorer adaptive life functioning in the long term.

From the Stanley Foundation Research Unit, St. Davnet’s Hospital, Monaghan (JQ, MM, JLW), St. John of God Hospital, Co Dublin (AL), the Department of Mathematics, Dublin Institute of Technology, Dublin (AK), and the Depart-ment of Clinical Pharmacology, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin (JQ, JLW), Ireland.

Address reprint requests to John L. Waddington, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, 123 St. Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland.

Received August 19, 1999; revised December 13, 1999; accepted January 11, 2000.

Methods and Materials

This study involved 41 inpatients in St. Davnet’s Hospital, Monaghan, a long-term care facility in rural Ireland, who satisfied the Washington University criteria of Feighner and colleagues (1972) for schizophrenia. These individuals were the survivors (85%) among the 48 patients studied previously by Scully et al (1997b); the remaining cases were deceased through natural causes. Patient records were reviewed to determine demographic and medication variables. Age at onset was opera-tionalized as age at first recorded contact with a psychiatric service, and duration of initially unmedicated psychosis as the time from age at onset to age at first recorded prescription of an antipsychotic; thereafter, duration of antipsychotic treatment and of interpolated antipsychotic-free intervals were determined from the same records. Adaptive life functioning was assessed using the Social-Adaptive Functioning Evaluation (SAFE). This 17-item instrument defines in increasing scores the severity of impairment in critical adaptive functioning domains, such as self-care, interpersonal competence and adjustment, and miscel-laneous life skills such as cooperativeness. The SAFE is designed specifically for geriatric patients with chronic psychiatric illness in an institutional setting; ratings are made through observation, caregiver interviews, and patient interactions (Harvey et al 1997). General cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al 1975); execu-tive (frontal; Smith and Jonides 1999) cogniexecu-tive function was assessed using the Executive Interview (EXIT; Royall et al 1992), which is designed specifically for patients such as those studied here whose debilities preclude the use of instruments such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Royall et al 1992, 1993; Scully et al 1997a, 1997b). Additionally, in preliminary studies, we also explored the feasibility of assessing such patients for neurological soft signs (NSS) using the Neurological Evalu-ation Scale (Buchanan and Heinrichs 1989) and the Condensed Neurological Examination (Rossi et al 1990) and for craniofacial dysmorphogenesis using an anthropometric scale (Lane et al 1997).

In the primary, hypothesis-based analysis, SAFE score was set as the outcome variable, and multiple regression modeling was applied to identify independent predictor variables among the indicated temporal phases of illness and treatment, current medication, and demographic indices.

Results

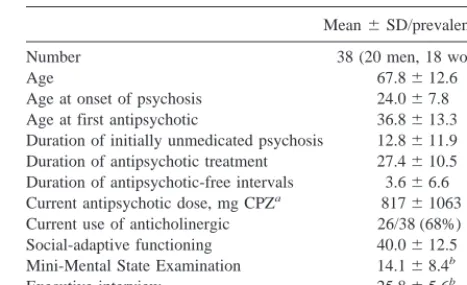

Complete data on each of the primary study variables were available for 38 of the 41 patients (93%) and it is to this group that all further discussion relates. Patients were generally older and characterized by poor social-adaptive functioning, with general and executive cognitive impair-ment (Table 1).

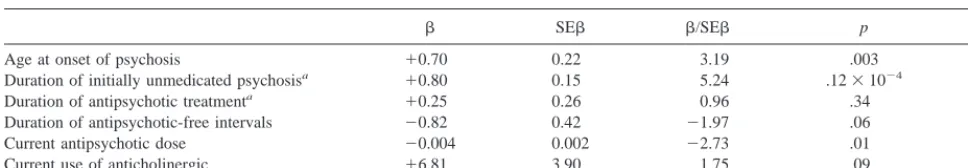

As indicated in Table 2, increasing SAFE score (greater functional impairment) was predicted prominently (p ,

.001) by increasing duration of initially unmedicated psychosis, which accounted for 22% of variance; by older age at onset (p 5 .003), which accounted for 3% of

variance; and by lower current dose of antipsychotics (p5

.01), which accounted for 6% of variance. No other variable made any significant independent contribution to the regression model, which accounted for 68% of vari-ance in SAFE score. Decreasing MMSE score (greater general cognitive impairment) was predicted only by increasing duration of initially unmedicated psychosis (b 5 20.55, SEb 50.13,b/SEb 54.12, p,.001, R25

31%); no other variable made any significant independent contribution to a regression model, which accounted for 47% of variance in MMSE score. No variable made any significant independent contribution to a regression model for EXIT score, which accounted only for 14% of the variance. In exploratory analyses, increasing NSS score (greater neurological abnormality) was predicted only by duration of initially unmedicated psychosis (p , .02); however, NSS were difficult to evaluate in these highly impaired patients because of problems in following exam-ination instructions (only n5 28 were able to comply), hence scores may reflect these deficits. Using prominence of palatal abnormalities and reduced mouth width as initial indices of craniofacial dysmorphogenesis in schizophrenia (Lane et al 1997), which were also difficult to evaluate in these patients (only n 5 35 able to comply), neither variable showed any material association with outcome measures.

Discussion

One of the main determinants of poor long-term outcome in schizophrenia is impairment in adaptive life function-ing, whereby many patients exhibit inability to care for themselves and thus become dependent on others. The causes of these deficits are multifactorial and involve negative symptoms, positive symptoms, cognitive dys-function, and the interactions between them, together with additional clinical, psychological, social, and situational

Table 1. Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Mean6SD/prevalence (%) Number 38 (20 men, 18 women) Age 67.8612.6 Age at onset of psychosis 24.067.8 Age at first antipsychotic 36.8613.3 Duration of initially unmedicated psychosis 12.8611.9 Duration of antipsychotic treatment 27.4610.5 Duration of antipsychotic-free intervals 3.666.6 Current antipsychotic dose, mg CPZa 81761063

Current use of anticholinergic 26/38 (68%) Social-adaptive functioning 40.0612.5 Mini-Mental State Examination 14.168.4b

Executive interview 25.865.6b

aMilligrams of chlorpromazine (CPZ) equivalents. bN537; one patient unable to complete.

164 BIOL PSYCHIATRY J. Quinn et al

factors (Harvey et al 1997). In our study, we have examined the lifetime trajectory of older inpatients with chronic schizophrenia by disassembling current age into sequential, temporal phases of illness. Among these con-stituent temporal phases and other study variables consid-ered, duration of initially unmedicated psychosis was a primary, substantive, and independent predictor of impair-ment in adaptive life functioning. This impairimpair-ment also was associated with lower current dosage of antipsychot-ics, which may reflect less recourse to aggressive antipsy-chotic therapy with increasing disability, and with older age at onset. As an “anchor” finding, in confirmation of our previous report (Scully et al 1997b), duration of initially unmedicated psychosis was the primary predictor of general (but not of executive) cognitive dysfunction. Our study extends adverse correlates of delayed interven-tion with antipsychotics from the psychological into the day-to-day functional domain that is responsible for plac-ing great personal and economic demand on health and social services.

It should be considered whether early impairment in adaptive life functioning might be associated, at least in part, with some delay in initiating antipsychotic therapy, although this issue is far from straightforward. Antipsy-chotics became available in rural Ireland only in the late 1950s, with the majority of the present patients receiving such medication for the first time into the 1960s. At admission, patients were acutely psychotic without evi-dencing the severity of their current impairments in adaptive life functioning. It may be more informative that duration of subsequently treated illness, although decades longer, failed to predict impairment in adaptive life func-tioning. The essential abandonment of insulin coma, re-serpine, and electroconvulsive therapies, which some of these patients received over the preneuroleptic era but which proved difficult to quantify, suggests that any contribution from such “treatments” would be small rela-tive to that of antipsychotic drugs. Any separate contribu-tion from medical comorbidity remains to be isolated.

Taken together, the present data elaborate the notion (Birchwood et al 1997; Loebel et al 1992; McGlashan and

Johannessen 1996) of the early phase of psychotic illness as a vulnerable period over which adverse biologic and psychosocial changes occur; thus, psychosis over this phase may reflect, at least in part, a process that is associated with increasing impairment unless ameliorated by antipsychotics. Factors operating over later phases of illness are also likely to influence long-term outcome, however. The present findings are consistent with some form of “progressive” process (Waddington et al 1998), particularly over the first several years following the emergence of psychosis, which is associated with accrual of functional deficits that encompass self-care, interper-sonal competence and adjustment, and life skills, but which may be mitigated in part by early and effective intervention with antipsychotics. Nonetheless, the extent of variance in SAFE score that is accounted for by duration of initially unmedicated psychosis would indicate that functional outcome is influenced also by additional factors, which may be remediable by medication or alternative interventions. The present inpatient population has the advantage of considerable homogeneity for overall course of illness; however, the extent to which findings deriving from inpatients of this age and chronicity might generalize to other patient groups (including those remit-ting spontaneously or discharged from hospital and treated in the community) and the nature of any “progressive” process remain to be determined.

Supported by an International Centre Grant from the Stanley Foundation.

References

Birchwood M, McGorry P, Jackson H (1997): Early intervention in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 170:2–5.

Buchanan RW, Heinrichs DW (1989): The Neurological Evalu-ation Scale: A structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 27:335– 350.

Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA, Winokur G (1972): Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 26:57– 63.

Table 2. Multiple Regression Model for Social-Adaptive Functioning Evaluation Score

b SEb b/SEb p R2

Age at onset of psychosis 10.70 0.22 3.19 .003 .03 Duration of initially unmedicated psychosisa 10.80 0.15 5.24 .1231024 .25

Duration of antipsychotic treatmenta 10.25 0.26 0.96 .34 .55

Duration of antipsychotic-free intervals 20.82 0.42 21.97 .06 .59 Current antipsychotic dose 20.004 0.002 22.73 .01 .65 Current use of anticholinergic 16.81 3.90 1.75 .09 .68

Gender was rejected from the model.

aBecause of a negative correlation (r5 2.55) between duration of initially unmedicated psychosis and duration of antipsychotic treatment, the effects of leaving out

each of these predictor variables was examined in turn. When duration of initially unmedicated psychosis was excluded, the only significant coefficient related to current antipsychotic dose; when duration of antipsychotic treatment was excluded, close agreement was found between the initial and reduced regression models.

Adaptive Life Functioning in Schizophrenia BIOL PSYCHIATRY 165

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR (1975): “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12:189 –198. Harvey PD, Davidson M, Mueser KT, Parrella M, White L,

Powchik P (1997): Social-Adaptive Functioning Evaluation (SAFE): A rating scale for geriatric psychiatric patients.

Schizophr Bull 23:131–145.

Lane A, Colgan K, Moynihan F, Burke T, Waddington JL, Larkin C, et al (1996): Schizophrenia and neurological soft signs: gender differences in clinical correlates and antecedent factors. Psychiatry Res 64:105–114.

Lane A, Kinsella A, Murphy P, Byrne M, Keenan J, Colgan K, et al (1997): The anthropometric assessment of dysmorphic features in schizophrenia as an index of its developmental origins. Psychol Med 27:1155–1164.

Loebel AD, Lieberman JA, Alvir JMJ, Mayerhoff DI, Geisler SH, Szymanski SR (1992): Duration of psychosis and out-come in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 149: 1183–1188.

McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO (1996): Early detection and intervention with schizophrenia: Rationale. Schizophr Bull 22:201–222.

Rossi A, De Cataldo S, Di Michele V, Manna V, Ceccoli S, Stratta P, et al (1990): Neurological soft signs in schizophre-nia. Br J Psychiatry 157:735–739.

Royall DR, Mahurin RK, Gray KF (1992): Bedside assessment of executive cognitive impairment: the Executive Interview.

J Am Geriatr Soc 40:1221–1226.

Royall DR, Mahurin RK, True JE, Anderson B, Brock IP,

Freeburger L, et al (1993): Executive impairment among the functionally dependent: Comparisons between schizophrenia and elderly subjects. Am J Psychiatry 150:1813–1819. Scully PJ, Coakley G, Kinsella A, Waddington JL (1997a):

Executive (frontal) dysfunction and negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Apparent gender differences in “static” v. “progressive” profiles. Br J Psychiatry 171:154 –158.

Scully PJ, Coakley G, Kinsella A, Waddington JL (1997b): Psychopathology, executive (frontal) and general cognitive impairment in relation to duration of initially untreated versus subsequently treated psychosis in chronic schizophrenia.

Psychol Med 27:1303–1310.

Smith EE, Jonides J (1999): Storage and executive processes in the frontal lobes. Science 283:1657–1661.

Szymanski SR, Cannon TD, Gallacher F, Erwin RJ, Gur RE (1996): Course of treatment response in first episode and chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 153:519 –525. Waddington JL, Lane A, Larkin C, O’Callaghan E (1999):

The neurodevelopmental basis of schizophrenia: Clinical clues from cerebro-craniofacial dysmorphogenesis and the roots of a lifetime trajectory of disease. Biol Psychiatry 46:31–39.

Waddington JL, Lane A, Scully PJ, Larkin C, O’Callaghan E (1998): Neurodevelomental and neuroprogressive processes in schizophrenia: Antithetical or complementary over a life-time trajectory of disease? Psychiatr Clin North Am 21:123– 149.

Wyatt RJ (1991): Neuroleptics and the natural course of schizo-phrenia. Schizophr Bull 17:325–351.

166 BIOL PSYCHIATRY J. Quinn et al