Symptomatic and Functional Outcome in Affective and

Nonaffective Psychosis

Mauricio Tohen, Stephen M. Strakowski, Carlos Zarate, Jr., John Hennen,

Andrew L. Stoll, Trisha Suppes, Gianni L. Faedda, Bruce M. Cohen,

Priscilla Gebre-Medhin, and Ross J. Baldessarini

Background: The McLean–Harvard First-Episode

Project recruited affective and nonaffective patients at their first lifetime psychiatric hospitalization.

Methods: Baseline evaluation and 6-month follow-up in 257 cases yielded recovery outcomes defined by syndro-mal (absence of DSM-IV criteria for a current episode) and functional (vocational and residential status at least at baseline levels) status. Time to recovery was assessed by survival analysis, and risk factors by multivariate logistic regression.

Results: Syndromal recovery was attained by 77% of cases over an average of 84 days. By diagnostic group, syndromal recovery rates ranked (p⫽.001) major affec-tive disorders (81%) ⬎ nonaffective acute psychoses (74%)⬎schizoaffective disorders (70%)⬎schizophrenia (36%). Functional recovery was significantly associated to syndromal recovery, diagnosis, shorter hospitalization normalized to year, and older age at onset. Average hospital stay declined across the study period, but recov-ery did not vary with year of entry.

Conclusions: Syndromal recovery was achieved by nearly one half of patients within 3 months of a first lifetime hospitalization for a psychotic illness, but functional recovery was not achieved by 6 months in nearly two thirds of patients who had attained syndromal recovery. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48:467– 476 © 2000 Society of Bi-ological Psychiatry

Key Words: First episode, function, length of stay,

outcome, psychotic disorders, recovery

Introduction

M

any studies have been conducted to define the course of psychotic disorders and identify predic-tors of their outcome; however, most outcome studies in psychotic disorders have involved patients considered to have schizophrenia and initiated follow-up at differ-ent stages of illness; very few have included patidiffer-ents with affective disorders (Beiser et al 1988, 1989; Bromet et al 1996; Craig et al 1997; Leff et al 1992; Tohen et al 1990a). Findings from such studies have been somewhat variable and are inconclusive, in part, owing to inclusion of newly and chronically ill subjects (Tohen 1991; Zis and Goodwin 1979). This situation has encouraged greater interest in prospective studies of first-episode patients with schizophrenia (Biehl et al 1986; Bromet et al 1996; Craig et al 1997; Gupta et al 1997; Johnstone et al 1990; Kane et al 1982; Lay et al 1997; Leff et al 1992; Lieberman et al 1993; Ram et al 1992; Schubart et al 1986; Scottish Schizophrenia Research Group 1989; Tohen 1991; Tohen et al 1990b, 1992a, 1996; Varma et al 1996; Ventura et al 1992) and bipolar disorder (Fennig et al 1996; Strakowski et al 1998; Tohen et al 1990b, 2000), as well as in the prodomal phase of schizophrenia (McGorry et al 2000). Studies begun at the start of the illnesses promise early identification of clinical and biological factors that may help to characterize patients with specific disorders as well as serve to predict their later course and outcome. Based on this background, The McLean–Harvard First-Episode Project has been observing a large number of first-episode psychotic patients with a range of DSM-IV diagnoses, prospectively, from their first lifetime hospital-ization. We recently reported recovery results including only patients with psychotic affective disorders (Tohen et al 2000). This report considers 1) rates and elapsed time to syndromal recovery, 2) occupational and residential mea-sures of functional recovery, and 3) factors associated with recovery in 257 patients with affective and nonaffective From The International Consortium for Bipolar Disorders Research; theConsoli-dated Department of Psychiatry & Neuroscience Program, Harvard Medical School, Boston (MT, JH, ALS, BMC, RJB) and Bipolar & Psychotic Disorders Program, McLean Hospital, Belmont (JH, PG-M, RJB), Massachusetts; Lilly Research Laboratories, Indianapolis, Indiana (MT); the Department of Psychi-atry, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio (SMS); the Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts, Worcester (CZ); the Department of Psychiatry, Univeristy of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas (TS); and Lucio Bini Psychiatric Center of New York, New York (GLF). Address reprint requests to Mauricio Tohen, M.D., Dr. PH, Lilly Research

Laboratories, Indianapolis IN 46285.

Received February 10, 2000; revised May 3, 2000; accepted May 5, 2000.

© 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry 0006-3223/00/$20.00

psychotic disorders at 6 months after their first psychiatric hospital admission.

Methods and Materials

The McLean–Harvard First-Episode Project was initiated in 1989 and has been active continuously since then. In this prospective, naturalistic follow-up study, treatment is not con-trolled by the investigators, although information about treatment is collected during hospitalization and throughout follow-up. Patients who presented with a psychotic syndrome were diag-nosed by DSM-III-R (from 1989 to 1994) or DSM-IV criteria since 1994 (American Psychiatric Association 1994), with all diagnoses adapted to meet DSM-IV criteria for this report. Subjects were recruited from the inpatient units of McLean Hospital, a main psychiatric teaching hospital of Harvard Med-ical School.

Patients included met the following criteria: 1) age 16 years or older; 2) in a first lifetime episode of a clinically defined psychotic illness (including thought disorder, hallucinations, delusions, or grossly disorganized behavior at the time of first hospitalization) without symptomatic remission since onset; 3) meeting DSM-IV criteria for a principal diagnosis of schizophre-nia, schizophreniform, schizoaffective, bipolar, or major depres-sive disorders with psychotic features, delusional disorder, brief reactive psychosis, or psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS); and 4) providing written informed consent based on McLean Hospital institutional review board approval. Exclusion criteria were 1) presence of acute intoxication or a withdrawal syndrome associated with drug or alcohol abuse, or delirium of any cause; 2) previous psychiatric hospitalizations, unless for alcohol or substance abuse detoxification; 3) presence of mental retardation or other organic mental disorder; 4) duration of illness of⬎1 year; and 5) prior treatment with an antipsychotic agent or mood stabilizer for a total of⬎3 months. A specially trained research assistant screens potential subjects by daily review of admission notes of all newly admitted patients with psychotic symptoms, as considered in preadmission assessments and verified by daily reviews with treating psychiatrists on each inpatient unit.

Baseline Measures

DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses (American Psychiatric Association 1994) were determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM—patient version (SCID-P; Spitzer et al 1988) carried out by professional raters (masters-level training and more than a year of clinical experience). Final diagnoses were ascertained with a best-estimate diagnostic procedure recommended by Leckman et al 1982). Next, a detailed clinical narrative was prepared using all available information (SCID-P, medical records, and interviews of family members and primary treating clinicians). This narrative was presented to two psychiatrists with expertise in psychotic disorders, and a best-estimate procedure determined primary and comorbid diagnoses. As part of the best-estimate procedure, time of onset, defined as fulfilling DSM criteria for any of the psychotic disorders under study, was determined.

Clinical and demographic variables recorded at baseline in-cluded age, gender, race, days of hospital length of stay (LOS), years of education, and employment status. Also, comorbidity factors assessed included 1) other DSM Axis I disorders (current and lifetime), 2) comorbid alcohol or other substance abuse (current and lifetime), and 3) concurrent medical or neurologic illness. This information was obtained from medical records, SCID-P examination, and from the patient, relatives, and respon-sible clinicians, by research assistants trained to obtain such data reliably. They evaluated patients within 72 hours of admission and weekly thereafter until discharge.

Assessment scales included an expanded version of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Lukoff et al 1986) with 35 items (rated for severity, 1–7) plus an overall sum score (Tohen et al 1992a, 2000), the Clinical Global Impressions (CGI; Guy 1976) and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; 0 –100 scale; American Psychiatric Association 1994) scales. Occupa-tional status was rated with the Modified VocaOccupa-tional Status Index (MVSI), and residential status rated with a Modified Location Code Index (MLCI; Dion et al 1988; Tohen et al 1990a, 1992a, 1996, 2000). Baseline occupational level and residential status were rated as the highest level achieved within the year before admission, based on information collected from medical records and family members as well as patients.

Outcome Measures

Patients were examined 6 months after hospital admission by an experienced professional rater (PG-M) kept blind to the baseline information. Follow-up information was obtained by telephone or by direct interview, as reported previously (Tohen et al 1990a, 1992a, 2000). If a subject could not be interviewed by telephone or face to face, follow-up information was obtained from a close relative or another member of the patient’s household. Of the reported follow-up assessments, 90% were by telephone, 60% were with the subject only, and 40% with relatives and friends with or without the subject.

In follow-up interviews, information elicited included socio-demographic changes, the course of the primary and comorbid disorders, occupational and residential functional status, diagnos-tic status to define syndromal recovery, and estimated time of such recovery (days since hospital admission). Follow-up inter-views also included the MVSI and MLCI functional level scales and the GAF. A statement of each subject’s general life satis-faction was also rated, as 1, very good; 2, good; 3, fair; 4, poor; and 5, very poor.

Syndromal recovery was defined as no longer meeting criteria

for an ongoing episode of illness (Frank et al 1991; Prien et al 1991; Tohen et al 2000). These included a CGI score of 2 and specific operational criteria, as follows:

1. For mania, the DSM mania “A” criteria were 3 in severity, no mania “B” criteria were⬎3, and two B criteria were scored 3.

2. For major depression with psychotic features, no DSM criteria were⬎3, and not more than three were rated 3. 3. For schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder, no

4. For delusional disorder and psychosis NOS, no affective, delusional, or hallucinatory symptoms were rated⬎2.

Subjects with schizoaffective disorder had to meet recovery criteria for both schizophrenia and either mania or depression. In addition, syndromal recovery criteria require that these condi-tions be sustained for at least 8 weeks, and latency to the start of this interval was scored in days from hospital admission.

Functional recovery was operationally defined categorically

by comparing MVSI (vocational status) and MLCI (living situation) ratings obtained at admission and at 6-month follow-up. Functional recovery by 6-month follow-up requires a return to at least the premorbid level of both vocational and residential functioning, plus attainment of a rating of 1–5 for occupational and 1– 4 for residential levels, as defined above.

Data Analysis

Interrater reliability was evaluated for the SCID-P for primary (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]⫽ .92) and secondary (ICC⫽.90) diagnoses (Tohen et al 1990a, 1992a, 1996, 2000). High interrater reliability was also obtained for the 35-item BPRS (ICC⫽.96; Tohen et al 1990a, 1992a, 1996, 2000; Zarate et al 1997b). Good to excellent agreement between telephone and in-person interviews was also obtained (ICC⫽.90; Revicki et al 1997; Tohen et al 1990a).

By having the same investigator (PG-M) conduct all the follow-up assessments, reliability for the recovery ratings across the different years of recruitment was assured.

Each subject was first designated as recovered or not recov-ered by 6 months, based on the syndromal and functional criteria just defined. Continuous demographic and clinical variables were dichotomized to yield meaningful contrasts and to facilitate estimates of odds ratios (ORs). Selected categoric variables also were recoded to afford simple, meaningful contrasts. Age at onset was trichotomized at 25, 26 – 49, and 50 years, and type of onset or prodrome was coded as rapid (1– 6 months) or gradual (⬎6 months). Diagnostic subgroup clusters defined by principal discharge DSM diagnostic codes were 1) major affective disor-ders with psychotic features (manic, mixed, or NOS bipolar disorders, or major depression), 2) acute nonaffective psychotic disorders (schizophreniform, schizoaffective, delusional, or psy-chotic NOS), 3) schizoaffective disorders, and 4) schizophrenia. Admission year (1989 –1996) was a categoric variable. Since average LOS diminished yearly, individual LOS (days) was normalized by ranking LOS for each year of admission and forming binary variables to characterize hospitalizations, as

shorter, 25th, and longer, 75th percentile for LOS in each year.

Individual BPRS scale items were dichotomized as severe (including ratings of 5–7) and nonsevere (0 – 4). Depressive, manic, and psychotic subtotal ratings of the 35-item BPRS (Lukoff et al 1986; Tohen et al 1990a, 1996) also were dichot-omized to indicate presence or absence of severe item scores (5–7), and BPRS total scores were median split to yield high/low scoring subgroups.

Syndromal and functional 6-month recovery rates were com-pared with contingency tables (2

). Both types of recovery were considered within diagnostic and other subgroups of interest

defined in Results and compared with 6-month GAF scores with Mann–Whitney rank sum nonparametric methods. Frequencies of categoric variables in recovery groups were compared by cross-tabulations and2

tests or Fisher exact p (if cell size⬍10 subjects). Log-rank nonparametric tests were used to compare distributions of continuous variables in subgroups. Variables with suggestive (p ⬍ .20) bivariate associations with recovery status were considered candidates for multivariate analyses. Multiple logistic regression models evaluated candidate demo-graphic and clinical variables for independent association with syndromal and functional recovery. Deciles of fitted values and partial residual plot methods were used to check the goodness of fit of multivariate models (Hosmer and Lemeshow 1989). Ex-planatory variables with adjusted ORs significantly different (p ⬍ .05) from 1.0 were retained for final multiple logistic regression models. Finally, distributions of days to recovery were compared between demographic and diagnostic groups by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of times to defined levels of recovery, with SE or 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and Mantel–Cox log-rank 2

tests of statistical significance (Lee 1992). Averaged continuous data are reported as means⫾SDs. Statistical analyses were based on commercially available mi-crocomputer programs (Stata, Stata Corp., College Station, TX; Statview-II, Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA).

Results

Patient Population

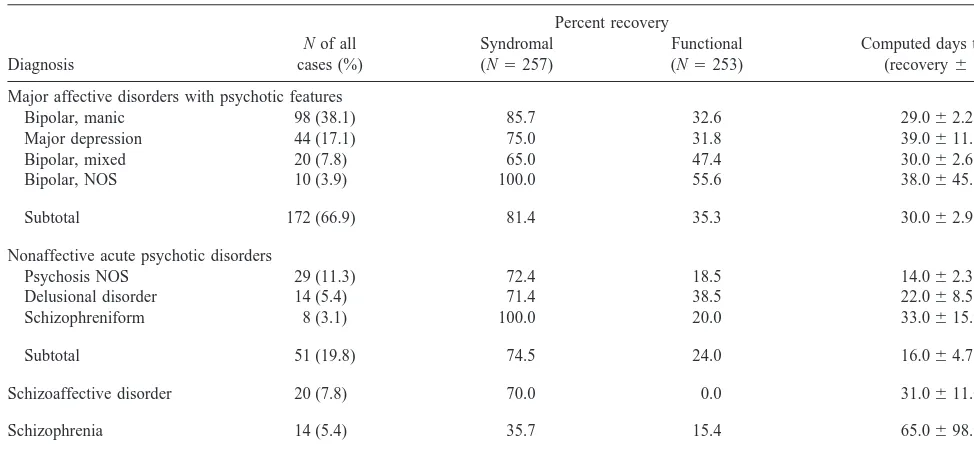

During the 6-year period of study recruitment from 1989 through 1995, 22,100 patients were hospitalized, of whom 784 (3.6%) were identified as in a first lifetime episode of psychotic illness. Of these, 296 (37.8%) were recruited (174 men [58.8%] and 122 women [41.2%]; mean⫾SD age at admission⫽31.9⫾5.0 years); 257 (86.8% of those recruited) provided 6-month follow-up data for syndromal outcome, and 253 (85.5%) for functional recovery. No significant differences between recruited and nonrecruited patients were found in a large number of demographic and clinical measures. Diagnostic categories included major affective disorders with psychotic features (N ⫽ 172, 66.9%), including bipolar disorder (N ⫽ 128, 49.8%) and major depression (N ⫽ 44, 17.1%); acute nonaf-fective psychotic disorders were next most frequent (N ⫽ 51, 19.8%); schizoaffective disorders (N ⫽ 20, 7.8%) and schizophrenia (N ⫽ 14, 5.5%) were least common (Table 1). This distribution of diagnoses was consistent with the recent case mix for all admissions for psychotic disorders at McLean Hospital, but may not generalize to other centers (Carpenter and Kirkpatrick 1988; Craig et al 1997; Lay et al 1997; Tohen et al 1992a; Varma et al 1996; Ventura et al 1992).

6-Month Recovery Rates

and residential criteria) by 29.2% (74/253) by 6 months after admission for a first lifetime hospitalization for psychotic illness. Of patients achieving syndromal recov-ery, 64.8% failed to reach functional recovery status within 6 months [2(1) ⫽ 12.2, p ⫽ .0005]. Women tended to gain syndromal recovery more often than men [81.1% vs. 71.5%; 2(1) ⫽ 3.11, p ⫽ .078], but functional recovery rates were similar in women and men [27.4% vs. 31.3%;2(1)⫽0.46, ns]. Occupational versus residential functional recovery rates, overall, were 39.1% (99/253) versus 73.1% (185/253). The mean functional recovery rate across the nine diagnoses (28.9⫾ 17.2%) was substantially less than syndromal recovery rate (75.0⫾19.5%) in all nine diagnostic categories encoun-tered (Table 1). Occupational and residential components of functional recovery appear to measure different aspects of recovery and were not correlated across diagnostic groups [r(1b) ⫽ .05, ns].

Syndromal 6-month recovery rates for four clusters of presumably related disorders ranked affective disorders (81.4%), acute nonaffective psychoses (74.5%), schizoaf-fective disorder (70.0%), and schizophrenia (35.7%), and differed highly significantly [2(3) ⫽ 16.0, p ⫽ .0012; Table 1). Functional recovery in the same clusters ranked acute nonaffective (74.5%), affective (35.3%), schizophre-nia (15.4%), and schizoaffective [0%;2(3)⫽ 2.61, ns).

Occupational criteria for recovery were evidently more difficult to attain because, for most diagnoses, these rates

(40.7 ⫾ 21.0%) were 1.74-fold lower than residential recovery rates (70.9⫾7.8%), and the average rate already cited for meeting both functional criteria (28.9%) was even lower. Rates based on occupational and residential criteria also were not correlated across the nine diagnostic groups [r(8) ⫽ .146, ns]. Residential recovery rates varied little across diagnostic groups, ranging from 75.9% in major affective disorders and 72.0% in acute nonaffec-tive psychoses, to 61.5% in schizophrenia and 60.0% in schizoaffective syndromes [2(3)⫽3.33, ns]. In contrast, occupational functional recovery rates varied significantly, from 45.3% in affective disorders to 38.5% in schizophre-nia and 28.0% in acute nonaffective psychoses, to a low of 15.0% in schizoaffective disorders [2(3) ⫽ 10.2, p ⫽ .017].

Syndromal recovery was also associated with higher 6-month GAF scores at 6 months after hospitalization: mean GAFs were 70.8 ⫾16.0 in syndromally recovered patients, but only 47.0 ⫾ 14.0 in nonrecovered subjects. Mean GAF values for functionally recovered versus non-recovered patients followed a similar trend (72.7⫾ 14.4 vs. 62.7 ⫾ 18.8). Both mean differences are highly significant (rank sum z ⫽ 8.40 and 3.70, respectively; both ps ⬍ .001). Similarly, subjective measures of pa-tients’ satisfaction with their life situation at 6-month follow-up were also strongly associated with syndromal and functional recovery. The mean patient satisfaction score (1–5 scale) among syndromally recovered patients

Table 1. Primary Diagnoses and Recovery in First-Psychosis Patients

Diagnosis

N of all

cases (%)

Percent recovery

Computed days to 25% (recovery⫾SE) Syndromal

(N⫽257)

Functional (N⫽253)

Major affective disorders with psychotic features

Bipolar, manic 98 (38.1) 85.7 32.6 29.0⫾2.2

Major depression 44 (17.1) 75.0 31.8 39.0⫾11.5

Bipolar, mixed 20 (7.8) 65.0 47.4 30.0⫾2.6

Bipolar, NOS 10 (3.9) 100.0 55.6 38.0⫾45.6

Subtotal 172 (66.9) 81.4 35.3 30.0⫾2.9

Nonaffective acute psychotic disorders

Psychosis NOS 29 (11.3) 72.4 18.5 14.0⫾2.3

Delusional disorder 14 (5.4) 71.4 38.5 22.0⫾8.5

Schizophreniform 8 (3.1) 100.0 20.0 33.0⫾15.9

Subtotal 51 (19.8) 74.5 24.0 16.0⫾4.7

Schizoaffective disorder 20 (7.8) 70.0 0.0 31.0⫾11.0

Schizophrenia 14 (5.4) 35.7 15.4 65.0⫾98.9

Total 257 (100.0) 77.0 29.2 29.0⫾2.3

All diagnoses were updated to accord with DSM-IV. Functional recovery required meeting both occupational and residential criteria. Functional recovery rates were less than syndromal rates for all categories (mean ratio of syndromal/functional recovery rates⫽2.64). Rates of syndromal recovery differed highly significantly among the four diagnostic clusters [2(3)⫽16, p⫽.0012], but functional recovery did not [2(3)⫽2.61, ns]. Values of days to 25% chance of syndromal recovery were computed by

survival analysis (not all disorders attained 50% rates within 6 months) and differed significantly among the four clusters [2(3)⫽9.24, p⫽.026]. NOS, not otherwise

for whom such data were available (N ⫽ 153) was 2.36 ⫾ 1.07, versus 3.31 ⫾ 1.05 among nonrecovered patients (N ⫽ 35; rank-sum z ⫽ 2.28, p⫽ .02). Also, for functionally recovered (N⫽56) versus nonrecovered (N ⫽ 132) subjects, these satisfaction scores averaged 2.25⫾1.01 versus 2.66⫾1.16 (rank sum z⫽2.28, p⫽ .02).

Time Course of Recovery

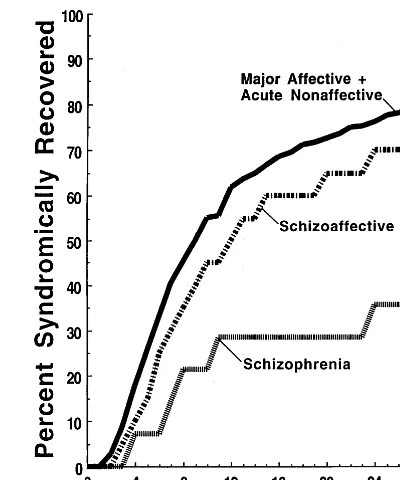

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was employed to evaluate the time course of recovery in subgroups of interest. The overall computed times to the 25% and 50% levels of syndromal recovery,⫾ SE, were 29.0⫾2.3 and 61.0⫾ 2.7 days, respectively (Figure 1). Women attained syndro-mal recovery significantly more rapidly than men, with their computed time to 50% recovery,⫾SE, at 43.0⫾9.0 versus 73.0 ⫾ 4.9 days (2 ⫽ 6.98, p ⫽ .0083; not shown). In addition, patients who had attained functional recovery (meeting both criteria) by 6 months, as expected, also reached 50% functional recovery (42.0⫾ 5.8 days) sooner than those who did not (73.0 ⫾ 14.7 days, a 1.74-fold difference;2⫽16.8, p ⬍ .0001; Figure 1).

Time functions were also compared for selected diag-nostic groups. Computed times to 25% syndromal

recov-ery for comparison across specific DSM-IV diagnoses and diagnostic groups showed mainly minor variations among disorders and averaged 29.0⫾2.3 days, overall (Table 1). These recovery time functions were found to be relatively brief among the acute nonaffective psychotic syndromes (16.0⫾4.7), intermediate among major affective (30.0⫾ 2.9) and schizoaffective (31.0 ⫾ 11.0) disorders, and longest in schizophrenia [65.0⫾98.9 days; Mantel–Cox 2

(3) ⫽ 9.24, p ⫽ .026]. Syndromal recovery time course functions are illustrated for three diagnostic groups: 1) major affective plus acute nonaffective psychotic dis-orders (bipolar diagnoses and unipolar major depression were pooled with acute nonaffective psychoses because their recovery time functions did not differ) were com-pared with the diagnostically ambiguous 2) schizoaffec-tive group and 3) those with a discharge diagnosis of schizophrenia [2(2) ⫽ 9.16, p ⫽ .010; Figure 2).

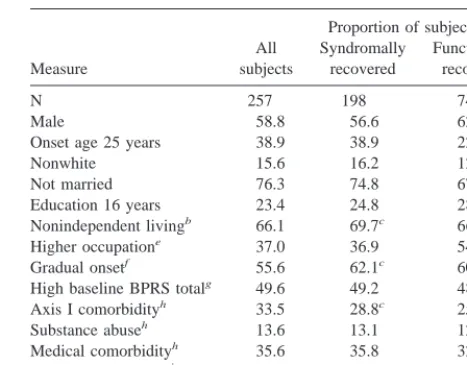

Factors Associated with 6-Month Recovery

Six factors were initially identified in bivariate analyses as having at least suggestive (p ⬍ .20) associations with

Figure 1. Actuarially computed Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of times to syndromal recovery after hospitalization for a first episode of psychotic illness. Shown are recovery functions for patients who did (highest line) or did not (lowest line) achieve functional recovery by both occupational and residential criteria at 6 months after admission [highly significantly different;

2

(1)⫽16.8, p⬍ .0001] and for all (N ⫽ 257) subjects.

Figure 2. Survival analysis (as for Figure 1) of time to syndro-mal recovery posthospitalization in first episode of (A) nonaf-fective acute psychotic disorders and major afnonaf-fective disorders with psychotic features [which did not differ and are pooled:

2

(1)⫽0.07, ns], (B) schizoaffective disorder, and (C) schizo-phrenia. Computed days to 25% of patients recovering are shown in Table 1. These functions differed significantly among the three groups [2

(2)⫽9.16, p ⫽ .01], and A as well as the pooled

A⫹B function differed from schizophrenia [both2

s(1)⫽8.09,

syndromal recovery in 198 subjects, versus nonrecovery in 59 subjects, and so were considered candidates for multi-variate analysis; these were 1) a major affective diagnosis, 2) relatively acute onset, 3) short hospitalization, 4) relatively high baseline GAF scores, 5) ability to live independently at follow-up (MLCI⬎4), and 6) absence of an additional Axis I comorbid condition. These factors and sex were entered into a multivariate logistic regression model; however, only diagnosis emerged as significant in the multivariate analysis (OR⫽ 2.04 [95% CI ⫽ 1.20 – 3.70], z ⫽ 2.33, p ⫽ .019), with greater recovery frequency among acute nonaffective and major affective groups, as compared with schizoaffective or schizophrenic groups. Surprisingly, various psychiatric, substance abuse, and medical comorbidity factors, as well as measures of illness severity at baseline assessment, had little ability to predict syndromal recovery.

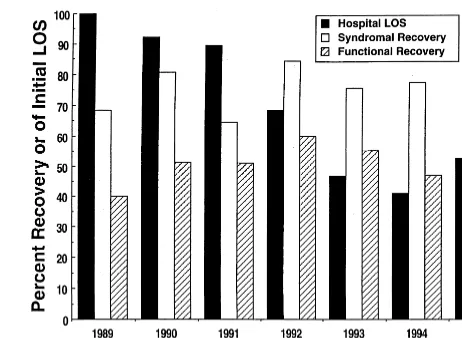

With respect to functional recovery (based on both occupational and residential criteria being at least at baseline levels at 6-month follow-up), five factors were initially identified as having at least suggestive (p⬍.20) associations with functional recovery in 74 subjects, ver-sus nonrecovery in 179 subjects, and so were determined to be candidates for multivariate analysis, along with sex. Four factors were sustained (p ⬍ .05) in multivariate analysis. In descending order of their apparent explanatory power, these ranked 1) having previously attained syndro-mal recovery, 2) major affective diagnosis, 3) LOS stan-dardized to admission year (shorter time in hospital was associated with favorable outcome, and longer stay with unfavorable), and 4) greater onset age. This four-factor model was highly significant overall [2(3)⫽ 31.6, p ⬍ .0001], and it accounted for a moderate amount of variance (10.4%; Table 2). A possible confounding was controlled by including in the same model LOS and year of entry into the study.

For both measures of outcome, model fit was evaluated

by the area under the receiver operating curve, the ratio of the likelihood functions (similar in interpretation to an r2 value, and an indication of explanatory power), and the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit statistic (Hosmer and Lemeshow 1989); all of these measures indicated accept-able levels of fit of both multivariate models to the data. Despite a sharp decline in the average hospital LOS across the years of entry into the study that might be expected to influence 6-month recovery status, there was no significant relationship between syndromal or func-tional recovery rates and year of entry into the study (Figure 3).

Discussion

The main findings from this study were that more than three quarters of newly psychotic patients attained syndro-mal recovery with currently standard, clinically indicated treatments within 6 months of a first lifetime psychiatric hospitalization, but that functional recovery was reached by fewer than a third of such patients. Generalizations from this finding to other settings and patient populations should be made cautiously. This study group was derived from admissions to a private, university-affiliated psychi-atric research and teaching center. Patients typically were referred from local hospital emergency rooms or univer-sity health services and had acute and severe psychotic symptoms that required treatment in a locked psychiatric unit. This referral pattern may be different from those of other institutions. One finding that particularly suggests cautious generalization is the small proportion of patient

Figure 3. Proportion of first-psychosis patients reaching syndro-mal and functional recovery by 6 months after hospital admission vs. year of study entry, with the corresponding mean length of hospital stay (LOS) for each year, as percent of the longest LOS (43.0⫾22.3 days in 1989). Length of stay declined steadily with

years (r⫽ ⫺.923, p⫽.003), but its decline was uncorrelated

with either form of recovery (r⫽ .495, ns).

Table 2. Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Associated with 6-Month Functional Recovery in First-Psychosis Patients

Factor Odds ratio (95% CI) z p

Syndromal recovery 2.85 1.20 – 6.81 2.36 .018

Diagnosisa 2.34 1.18 – 4.63 2.44 .015

Hospital LOSb 1.67 1.13–2.45 2.97 .003

Onset agec 1.02 1.00 –1.04 2.04 .042

Factors are defined and shown in bivariate analyses in Tables 1 and 2. Subjects (N ⫽ 253) were rated for functional recovery, which required meeting both vocational and residential criteria. The model is significant overall [2(3)⫽31.6, p⬍.0001] and accounts for 10.4% of the variance. CI, confidence interval; LOS, length of stay.

aRecovery was more likely with major affective and acute nonaffective

diagnoses, and least likely with schizophrenia.

bRelatively shorter hospitalizations favored recovery, and longer LOS

disfa-vored.

subjects meeting DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia (5.4%; Table 1). Instead, our finding pertains largely to the high proportion of patients presenting with affective dis-orders with psychotic features, or with various acute nonaffective psychoses. Study inclusion criteria of not being ill for more than 1 year and not being on psycho-tropic medications for more than 3 months limited the number of patients with schizophrenia. Therefore, any generalization of the schizophrenic cohort should be lim-ited to similar patients. Another limitation of this study was the lack of systematic information on admissions to other facilities in the area where patients with first-episode schizophrenia could have been admitted.

Important impressions arising from the present findings include the following:

1. A large proportion of first-episode psychotic pa-tients (77.0%) achieved syndromal or symptomatic recovery within 6 months of hospitalization. 2. The time course of syndromal recovery was such

that 25% of all patients recovered within 6 weeks, and 50% within 12 weeks for most disorders (Figure 1); only those diagnosed initially with schizophrenia failed to reach the 50% level of recovery within 6 months.

3. Many subjects (79.8%) failed to achieve functional recovery within 6 months (Table 1), even to the level of moderate independence, and nearly two thirds (64.8%) of those reaching syndromal recovery failed to attain functional recovery. Functional re-covery based on occupational level was less often achieved than functional recovery based on residen-tial status. Those who reached functional recovery achieved syndromal recovery earlier than those who did not (Figure 1).

Few predictive factors were significantly related to syndromal recovery in multivariate analysis, other than the diagnosis of a bipolar or major depressive syndrome with psychotic features or a nonaffective acute psychotic dis-order, although a relatively acute onset tended to be associated (Tables 2 and 3). Several factors were signifi-cantly associated with functional recovery, however. They included 1) having attained syndromal recovery, 2) diag-nosis of a major affective disorder or a nonaffective acute psychotic disorder, 3) relatively brief hospitalization, and 4) a relatively later age at onset (Table 2). Various medical, psychiatric, or substance abuse comorbidity fac-tors had little effect at this early stage of new psychotic illness, in contrast to expectations based on studies of populations with chronic psychotic illness (Drake et al 1996); however, a relatively small number of patients (N ⫽ 21) with a history of epileptic seizures were less

likely to recovery syndromally (p ⫽ .001) or function-ally (p ⫽ .04), based on multivariate modeling.

Another striking and unexpected finding was an evident lack of relationship of 6-month outcomes to the year of enrollment in this study between 1989 and 1996. We had previously observed a progressive diminution in percent improvement on standard rating scales (BPRS and CGI) between initial hospitalization and discharge, along with a largely economically driven shortening average length of hospitalization during the same years at the study site (Figure 3; Zarate et al 1997a). Both syndromal and functional recovery rates were similar across the years of entry into the study (Figure 3). These findings indicate that outcome at 6 months after hospitalization was largely unaffected by the marked recent decreases in average LOS. Apparently, many first-psychosis patients sustained the recovery process initiated during increasingly time-limited hospitalization (Figures 1 and 2). The fact that decreased LOS did not worsen functional recovery sug-gests that the improvement in functional outcomes may take place during the posthospitalization period.

Studies conducted at the University of Cincinnati have

Table 3. Characteristics of 257 First-Psychosis Patients Reaching Syndromal and Functional Recovery or Not within 6-Months after Hospitalization

Onset age 25 years 38.9 38.9 22.9a

Nonwhite 15.6 16.2 12.2

Not married 76.3 74.8 67.7a

Education 16 years 23.4 24.8 28.4 Nonindependent livingb 66.1 69.7c 66.2d

Higher occupatione 37.0 36.9 54.1d

Gradual onsetf 55.6 62.1c 60.8

High baseline BPRS totalg 49.6 49.2 48.5

Axis I comorbidityh 33.5 28.8c 25.7

Substance abuseh 13.6 13.1 12.2

Medical comorbidityh 35.6 35.8 32.4

Short hospitalizationi 26.8 29.8c 36.5a

BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.

aSignificantly different between functionally recovered and nonrecovered

subjects (p ⬍.05).

bModified Location Code Index rating⬎2.

cSignificantly different between syndromally recovered and nonrecovered

subjects (p ⬍.05).

dStatistical significance is indeterminate when outcome is defined by

occupa-tional and living situations.

eEmployed, student, homemaker (Modified Vocational Status Index rating⬍

3).

fProdrome 6 months [2⫽14.7, p⬍.001]. gBPRS total score above median at admission.

hCurrent Axis I, substance abuse or medical comorbidity [also, lifetime history

of such comorbidity was not related to outcome, although a history of epileptic seizures was more frequent with nonrecovery: 4.04 vs. 22.0%;2(1)⫽19.6, p⬍

.001].

focused on similar outcomes. Keck and collaborators (1998), in a 1-year follow-up study of 134 multiple-episode bipolar patients, found that syndromic recovery occurred in 26% of patients and functional recovery in 24%. The relatively higher recovery rates in our bipolar subgroup may be explained by the inclusion of first-episode patients only. A similar study from the same group in the University of Cincinnati focused on first-episode affective psychosis (Strakowski et al 1998). In that study 56% of the patients achieved syndromic recovery and 35% achieved functional recovery. In our study the 32.6% rate of functional recovery is remarkably similar to the Cin-cinnati rate; however, the 85.7% of syndromic recovery in our study is clearly higher than the 56% figure reported by Strakowski and collaborators. In the Cincinnati study higher socioeconomic status (SES) was a predictor of both symptomatic and functional recovery. It is possible that the higher SES of the McLean patients may explain the higher rates of symptomatic recovery.

Our findings have clear implications for the long-term aftercare of patients with psychotic disorders. It is encour-aging that a majority of patients achieved a substantial level of symptomatic recovery within even 3 months of aftercare; however, this was not the case with patients initially diagnosed with schizophrenia. Moreover, it is especially disturbing that nearly two thirds of patients considered syndromally recovered had not recovered func-tionally by 6 months after hospitalization, in that they failed to return even to their baseline levels of residential and, particularly, occupational functioning, or to minimal levels of functional independence. For many patients, even baseline functioning may already have been compromised due to prodromal illness or comorbidity for some months before the index hospitalization. It remains to be deter-mined how many subjects, in which diagnostic groups, will go on to further improvements or relapses with longer follow-up, and that aspect of the investigation is ongoing. An issue that has been addressed by our group and other authors (Fennig et al 1994; Tohen et al 1992b) is the shift of diagnosis. In this study, reassessment of diagnosis was conducted at the 2-year follow-up; thus, this information is not available for the 6-month follow-up period.

The inconsistency between syndromal and functional recovery reported here parallels clinical experience, in which substantial symptomatic recovery in acute phases of psychotic illnesses may occur before, or without, return to a baseline level or to a substantially improved functional status. Even with major resolution of acute symptoms, independent living, interactions with other persons, and, particularly, ability to work productively may continue to be compromised for prolonged periods or may result in sustained disability, with its associated high indirect costs to society (Greenberg et al 1993; Wyatt et al 1997; Wyatt

and Henter 1995). There may be particular difficulties associated with first episodes and the new experience of psychotic illness, resulting in denial or demoralization that can complicate efforts at treatment and rehabilitation. We suggest that future research on treatment and outcomes in new psychotic illness should emphasize functional out-come as well as symptomatic improvement.

These findings highlight a growing appreciation that symptom-based assessments are insufficient to assure long-term functional recovery and an improved quality of life in psychotic patients. Recent improvements in diag-nostic and clinical assessment methods in psychiatry have supported advances in the scientific understanding of psychotic disorders. Nevertheless, in our opinion even modern psychiatry—including its outcomes research— remains excessively preoccupied with medically oriented, symptomatic assessments. These measures are important, but represent an incomplete evaluation of clinical status and level of recovery. Accordingly, we strongly encourage further attempts to improve and to include various func-tional assessments in studies of treatment effects and outcomes, particularly early in the course of the potentially chronic and disabling psychotic disorders. The assessment of functional recovery needs to be considered in clinical trials. New treatments need to be compared to older treatments in terms of their ability to improve functional outcomes. In addition, the role of rehabilitation treatments at the onset of major psychiatric disorders needs to be evaluated to determine if new treatments provide long-term benefits. Challenges include the need to assess baseline functional levels in light of relevant premorbid disability and to understand differences between ability to live more or less independently and ability to work productively and gainfully.

In conclusion, although 77% of patients with psychotic disorders were judged to have achieved substantial symptom-atic recovery within 6 months of a first hospitalization, 65% of these patients did not regain their premorbid functional status as defined by occupational activities and living situa-tions indicative of at least minimal independence, and those diagnosed with schizophrenia did especially poorly by both syndromal and functional criteria for recovery. The findings support further efforts to improve functional as well as symptomatic assessments of psychotic patients.

Supported in part by United States Public Health Service Grants Nos. MH-04844, MH-01948, and MH-47370; grants from the Atlas Founda-tion and the Bruce J. Anderson FoundaFounda-tion; and the McLean Private Donors Neuropsychopharmacology Research Fund.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994): Diagnostic and

Sta-tistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington,

DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Beiser M, Iacono WG, Erickson D, editors (1989): The Validity

of Psychiatric Diagnosis. New York: Raven.

Beiser M, Jonathan E, Fleming MB, Iacono WG, Lin T (1988): Refining the diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder. Am J

Psychiatry 145:695–700.

Biehl H, Maurer K, Schubart C, Krumm B, Jung E (1986): Prediction of outcome and utilization of medical services in a prospective study of first onset schizophrenics: Results of a prospective 5-year follow-up study. Eur Arch Psychiatr

Neurosci 236:139 –147.

Bromet EJ, Jandorf L, Fennig S, Lavelle J, Kovsznay B, Ram R, et al (1996): The Suffolk County Mental Health Project: Demographic, premorbid and clinical correlates of six-month outcome. Psychol Med 26:953–962.

Carpenter WT Jr, Kirkpatrick B (1988): The heterogeneity of the long-term course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 14:645– 652.

Craig TJ, Bromet EJ, Jandorf L, Fennig S, Tanenberg-Karant M, Ram R, Rosen B (1997): Diagnosis, treatment, and six-month outcome status in first-admission psychosis. Ann Clin

Psy-chiatry 9:89 –97.

Dion GL, Tohen M, Anthony WA, Waternaux CM (1988): Symptoms and functioning of patients with bipolar disorder six months after hospitalization. Hosp Com Psychiatry 39: 652– 657.

Drake RE, Mueser KT, Clark RE, Wallach MA (1996): The course, treatment, and outcome of substance disorder in persons with severe mental illness. Am J Orthopsychiatry 66:42–51.

Fennig S, Bromet J, Tananberg Karant M, Ram R, Jandorf L (1996): Mood-congruent versus mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms in first-admission patients with affective disorder.

J Affect Disord 37:23–29.

Fennig S, Kovasznay B, Rich C, Ram R, Pato C, Miller A, et al (1994): Six-month stability of psychiatric diagnoses in first-admission patients with psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 151: 1200 –1208.

Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, et al (1991): Conceptualization and rational for consen-sus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder: Remis-sion, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 48:851– 855.

Greenberg PE, Stiglin E, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER (1993): The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry 54:405– 418.

Gupta S, Andreasen NC, Arndt S, Flaum M, Hubbard WC, Ziebell S (1997): The Iowa longitudinal study of recent onset psychosis: One-year follow-up of first episode patients.

Schizophr Res 23:1–13.

Guy W (1976): ECDEU Assessment Manual for

Psychopharma-cology, revised, National Institute of Mental Health

Publica-tion ADM 76-338. Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education and Welfare.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (1989): Applied Logistic Regression. New York: Wiley.

Johnstone EC, MacMillan JF, Frith CD, Benn DK, Crow TJ (1990): Further investigation of predictors of outcome fol-lowing first schizophrenic episodes. Br J Psychiatry 157:182– 189.

Kane JM, Rifkin A, Quitkin F, Nayak D, Ramos-Lorenzi J (1982): Fluphenazine vs. placebo in patients with remitted, acute first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 39: 70 –73.

Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, West SA, Sax KW, Harkins JM, et al (1998): 12-month outcome of patients with bipolar disorder following hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am J Psychiatry 155:646 – 652.

Lay B, Schmidt MH, Blanz B (1997): Course of adolescent psychotic disorder with schizoaffective episodes. Eur Child

Adolesc Psychiatry 6:37– 41.

Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson WD, Belanger A, Weissman MM (1982): Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: A methodological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 39:879 – 883.

Lee ET (1992): Statistical Methods for Survival Data Analysis. New York: Wiley.

Leff J, Sartorius N, Jablensky A, Korten A, Ernberg G (1992): The International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia: Five-year follow-up findings. Psychol Med 22:131–145.

Lieberman J, Jody D, Geisler S, Alvir JM, Loebel A, Szymanski S, et al (1993): Time-course and biologic correlates of treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen

Psychiatry 50:369 –376.

Lukoff D, Neuchterlein KH, Ventura J (1986): Manual for the expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Schizophr Bull 12:594 – 602.

McGorry PD, McKenzie D, Jackson HJ, Waddell F, Curry C (2000): Can we improve the diagnostic efficiency and pre-dictive power of prodromal symptoms for schizophrenia?

Schizophr Res 42:91–100.

Prien RF, Carpenter WT Jr, Kupfer DJ (1991): The definition and operational criteria for treatment outcome of depressive disorder: A review of the current research literature. Arch Gen

Psychiatry 48:796 – 800.

Ram R, Bromet EJ, Eaton WW, Pato C, Schwartz JE (1992): The natural course of schizophrenia: A review of first-admission studies. Schizophr Bull 18:185–207.

Revicki DA, Tohen M, Gyulai L, Thompson C, Pike S, Davis-Vogel A, Zarate CA Jr (1997): Telephone vs. in-person clinical and health status assessment interviews in patients with bipolar disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 5:75– 81. Schubart C, Krumm B, Biehl H, Schwarz R (1986):

Measure-ment of social disability in a schizophrenic patient group: Definition, assessment and outcome over two years in a cohort of schizophrenic patients of recent onset. Sociol

Psychiatry 21:1–9.

Scottish Schizophrenia Research Group (1989): The Scottish first episode schizophrenia study: Two-year follow-up. Acta

Psychiatr Scand 80:597– 602.

Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MD (1988):

Struc-tured Clinical Interview for DSM-III—patient version (SCID-P). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute.

hospitalization for affective psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55:49 –55.

Tohen M (1991): Course and treatment outcome in patients with mania. In: Mirin SM, Gossett JT, Grob MC, editors.

Psychi-atric Treatment. Advances in Outcome Research.

Washing-ton, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 127–142.

Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM Jr, Baldessarini R, Strakowski SM, Stoll AL, et al (2000): Two-year sydromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry 157:220 –228. Tohen M, Stoll AL, Strakowski SM, Faedda GL, Mayer PV,

Goodwin DS, et al (1992a): The McLean first-episode psy-chosis project: Six-month recovery and recurrence outcome.

Schizophr Bull 18:273–282.

Tohen M, Tsuang MT, Goodwin DC (1992b): Prediction of outcome in mania by mood-congruent or mood-incongruent psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry 149:1580 –1584. Tohen M, Waternaux CM, Tsuang MT (1990a): Outcome in

mania: A four-year prospective follow-up of 75 patients utilizing survival analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 47:1106 – 1111.

Tohen M, Waternaux CM, Tsuang MT, Hunt A (1990b): Four-year follow-up of 24 first-episode manic patients. J

Affect Disord 19:79 – 86.

Tohen M, Zarate CA Jr, Zarate SB, Gebre-Medhin P, Pike S

(1996): The McLean-Harvard first-episode mania project: Pharmacologic treatment and outcome. Psychiatr Ann 26: S444 –S448.

Varma VK, Malhotra S, Yoo ES, Jiloha RC, Finnerty MT, Susser E (1996): Course and outcome of acute nonorganic psychotic states in India. Psychiatr Q 67:195–207.

Ventura J, Neuchterlain KH, Pederson-Hardesty J, Gitlin M (1992): Life events and schizophrenic relapse after with-drawal of medication. Br J Psychiatry 161:615– 620. Wyatt RJ, Green MF, Tuma AH (1997): Long-term morbidity

associated with delayed treatment of first-admission schizo-phrenic patients. Psychol Med 27:261–268.

Wyatt RJ, Henter I (1995): An economic evaluation of manic-depressive illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 30: 213–219.

Zarate CA Jr, Tohen M, Baraibar G, Zarate SB, Baldessarini RJ (1997a): Shifts in hospital diagnostic frequencies: Bipolar subtypes, 1981–1993. J Affect Disord 43:79 – 84.

Zarate CA Jr, Weinstock L, Cukor P, Morabito C, Leahy L, Burns C, Baer L (1997b): Applicabiilty of telemedicine for assessing patients with schizophrenia: Acceptance and reli-ability. J Clin Psychiatry 58:22–25.