Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:58

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Tenure Perspectives: Tenured Versus Nontenured

Tenure-Track Faculty

Shane R. Premeaux

To cite this article: Shane R. Premeaux (2012) Tenure Perspectives: Tenured Versus Nontenured Tenure-Track Faculty, Journal of Education for Business, 87:2, 121-127, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.577111

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.577111

Published online: 15 Dec 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 435

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.577111

Tenure Perspectives: Tenured Versus Nontenured

Tenure-Track Faculty

Shane R. Premeaux

McNeese State University, Lake Charles, Louisiana, USA

The author examined a broad range of respondent perspectives on tenure-related issues in a survey of 1,583 professors at 321 Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB)-accredited business schools in all 50 states. Tenured and nontenured tenure-track university professors at AACSB-accredited business schools agreed that tenure is necessary. Survey results indicate that mean ratings for 9 of the 20 tenure issues investigated differed significantly between tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty members, down from 13 significant differences in 2001. Basically, even though the groups disagree on the impact of traditional tenure on teaching and research, both groups now embrace traditional tenure.

Keywords: AACSB, business school, faculty, tenure

The one unique perk that only faculty members enjoy is aca-demic tenure, and evidently most faculty members want this most revered benefit. Critics argue that tenure has evolved from a protection mechanism to teach and publish controver-sial ideas, to a guarantee of lifetime job security regardless of performance (Lataif, 1998; Margolin, 2007). According to some, the present tenure system protects underproductive faculty members who teach obsolete notions about business (Pearce, 1999). However, there may be other motives for tenure changes such as a desire to save money and to shift the delicate balanced partnership between administrators and faculty or simply to eliminate tenure. Approximately 90% of all four-year institutions and 99% of four-year public univer-sities have tenure systems, but only about 50% of all pro-fessors nationwide are tenured, down from approximately 66% in 2001 (Fogg, 2005; National Center for Education Statistics, 2003).

Some schools are taking what may seem like drastic mea-sures by abolishing departments and the tenured faculty in those departments. The University of Wisconsin–Madison cut over 120 tenured faculty and now have over 1,000 non-tenured faculty (Editorial Board, 2008). Tenure problems still exist despite a decrease in full-time, tenured faculty in colleges across the nation (Budd, 2006; Smith, 2000).

Correspondence should be addressed to Shane R. Premeaux, Mc-Neese State University, College of Business, Department of Management & Marketing, Box 92135, Lake Charles, LA 70609, USA. E-mail: spre-meaux@suddenlink.net

To avoid tenure related problems, more and more colleges and universities are using adjunct or part-time faculty as opposed to placing faculty in tenure-track positions (Budd; McGinn & Blake, 2000). Part-time or adjunct faculty now comprise over half the faculty in the United States (Buck, 2006).

Changing tenure may mean downsizing of selected faculty who historically have been protected by traditional tenure. Tenured faculty are often the most expensive to keep, and persistent cost-cutting efforts by administrators tend to focus on eliminating highly paid tenured faculty. A national study by the American Federation of Teachers found that non-tenure-track faculty members earned about $10,000 less a

year than those on the tenure track and $19,000 less than

tenured professors (Ryman, 2008).

Opponents of tenure contend that it protects lazy and un-productive professors, and thereby limits the available re-sources needed to offer the best education possible (Isfa-hani, 1998; Margolin, 2007). Critics contend that tenure has changed from a way to protect academic freedom to a system to protect job security, which hurts institutions by impairing their ability to adapt their curricula to changing student de-mands and making it harder for them to get rid of ineffective dead wood. “The decision to tenure has an accompanying long-term price tag that easily exceeds$1 million per

per-son” (Lederman, 2006, p. 12). Despite the cost, tenure may in fact have a positive impact on research productivity, with one study concluding that research productivity is positively correlated with tenure, but negatively correlated with years of employment (Chen, Gupta, & Hoshower, 2006).

122 S. R. PREMEAUX

Despite elimination efforts, tenure remains a strong shield of lifetime faculty protection at virtually all universities, but now most faculty are off the tenure track (Buck, 2006; Strauss, 2000). Tenure advocates argue that higher education is not the only field that offers job security. Other professions that require extensive education offer de facto tenure, such as law and medicine. Even government employees are vir-tually guaranteed lifetime employment after a probationary period. Tenure may help attract well-qualified individuals to higher education, because without job security protection some would opt for higher paying private-sector jobs. Tenure may benefit universities by helping to cap faculty salaries and by discouraging job hopping (Finkin, 1996; MacLeod, 2006).

Tenure was established for purposes related to academic freedom and the reasons for its existence are as valid at present as ever, possibly even more so. Tenure gives some assurance that faculty can be free thinkers without constantly having to live in fear of what might happen if they do not fall in line with whatever ill-conceived initiative is promoted. Tenure is obviously not an absolute defense against the wrath of those who would rather not have their true motives ex-posed, but it does provide some protection (Hughey, 2009).

Regardless of which viewpoint is correct, understanding faculty perspectives regarding tenure is essential. This study focuses on the perceptual differences between tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty with regard to tenure and its impact on higher education. A nontenured tenure-track faculty member is a professor who is on a track to ulti-mately be considered for tenure, as opposed to part-time or adjunct professors. Basically, if agreement between tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty members is the norm, many aspects of traditional tenure may well be preserved.

METHOD

I surveyed 411 Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) programs accredited at the undergrad-uate and gradundergrad-uate levels in the United States. AACSB is de-voted to the promotion and improvement of higher education in business administration and management. This devotion has lead to the establishment of standards that all accredited schools must meet to earn AACSB accreditation. Meeting these standards means that, among other achievements, fac-ulty must distinguish themselves, particularly in the areas of research and teaching. Faculty at AACSB-accredited schools are subject to similar performance expectations, and should therefore be fairly well informed regarding the issues ad-dressed here.

Surveys were mailed directly to six faculty members at each AACSB-accredited school, for a total of 2,466 faculty surveys. From the pool of faculty at each school, two full pro-fessors, two associate propro-fessors, and two assistant professors were randomly selected to receive surveys. A postage-paid

envelope was included so each respondent could return the completed questionnaire directly. A follow-up mailing was conducted six weeks after the initial mailing, and another three weeks after the follow-up. Response was extremely high, with 1,583 faculty members from 321 schools in all 50 states responding, for a response rate of over 64%.

Only faculty from AACSB-accredited schools were in-cluded in this survey because the environment in which they work, in terms of expectations in teaching, research, and ser-vice, should be similar. Additionally, the rigors of earning tenure should be somewhat similar. Although the actual re-quirements may differ in terms of numbers, percentages, and perceived quality, certainly all AACSB-accredited schools will evaluate faculty in the areas of teaching, research, and service before granting tenure. A merit-based tenure sys-tem, taking into account these three areas, is fairly common at most universities (Defleur, 2007). At the very least, fac-ulty members at most AACSB-accredited schools should be aware of the very basic performance requirements for faculty affiliated with accredited schools.

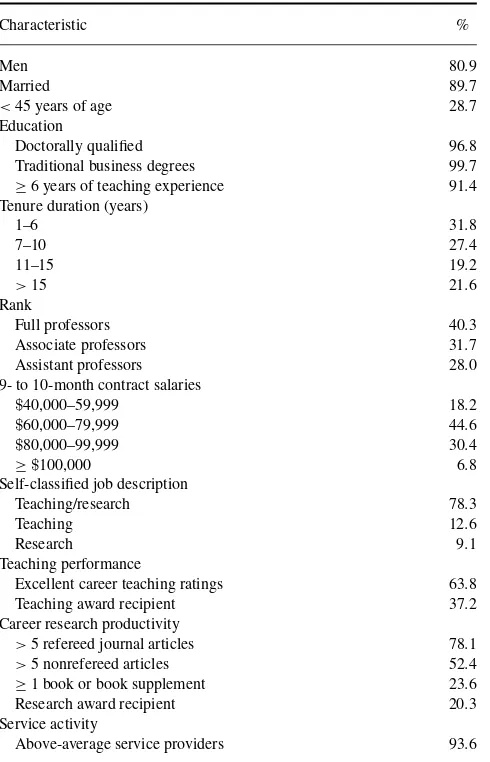

The demographic characteristics in Tables 1 and 2 reveal fairly definitive divisions between the various characteristics of the response group. Basically, based on self-reported re-sults, tenured (Table 1) and nontenured tenure-track (Table 2) faculty were quite effective in terms of teaching, research, and service. If this perceived level of productivity is accurate, then the majority of respondents would be somewhat compet-itive at most AACSB-accredited universities. The opinions of such faculty may reveal representative attitudes of tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty.

However, there may be a disconnect between faculty perceptions and reality regarding faculty productivity. For tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty the percent-age reporting excellence in teaching (63.8% and 69.1%, re-spectively) did not nearly parallel those receiving teaching excellence awards (37.2% and 38.2%, respectively). Sim-ilarly, a majority of tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty reported career research productivity of more than five refereed journal articles (78.1% and 67.6%, respec-tively), whereas only a small percentage of both groups re-ceived research awards (20.3% and 23.2%, respectively). Al-though this disconnect could be due to a variety of factors, such as the nonexistence of teaching and research awards or the criteria established to earn such awards, it is worth noting.

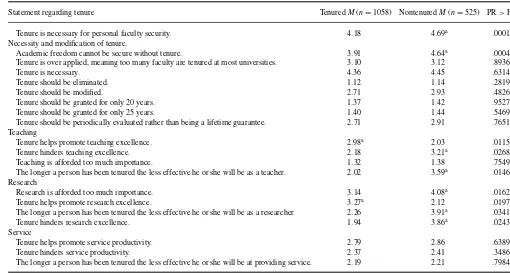

Tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty were asked to rate their level of agreement with the 20 tenure issues listed in Table 3. The 20 tenure issues rated in this study were initially gleaned from the literature and were used in the previous investigation (Premeaux & Mondy, 2002) and were included in other tenure studies. A pretest reaffirmed the importance of these variables and identified no other significant variables. To indicate the level of agreement, I used a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (complete disagreement) to 5 (complete agreement).

TABLE 1

Profile of Tenured Faculty Members (N=1,058)

Characteristic %

Men 80.9

Married 89.7

<45 years of age 28.7

Education

Doctorally qualified 96.8

Traditional business degrees 99.7

≥6 years of teaching experience 91.4

Tenure duration (years)

Full professors 40.3

Associate professors 31.7

Assistant professors 28.0

9- to 10-month contract salaries

$40,000–59,999 18.2

Excellent career teaching ratings 63.8

Teaching award recipient 37.2

Career research productivity

>5 refereed journal articles 78.1 >5 nonrefereed articles 52.4

≥1 book or book supplement 23.6

Research award recipient 20.3

Service activity

Above-average service providers 93.6

Note.Tenured faculty members comprised 66.84% of the respondents. All percentages are rounded, and nonresponse percentages are not shown.

The previous 2001 survey examined the same tenure-related issues that were evaluated in the present survey. The 2001 survey was conducted in the same manner and all of the institutions surveyed in 2001 were included in the present survey process. In addition, the data were analyzed and re-ported in the same manner in both surveys.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics in the form of frequency and crosstab-ulation tables were computed to get a feel for the data. A comparison was then made to determine if differences exist between the perceptions of tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty regarding tenure’s impact on higher education in business. Analyses of variance was used to compare the per-ceived importance assigned to each tenure issue by tenured

TABLE 2

Respondent Profile of Nontenured Tenure-Track Faculty Members (N=525)

Characteristic %

Men 69.2

Married 68.1

<45 years of age 67.4

Education

Doctorally qualified 98.7

Traditional business degrees 99.8

≥6 years of teaching experience 72.2

Rank

Full professors 18.6

Associate professors 27.2

Assistant professors 54.2

9- to 10-month contract salaries

$40,000–59,999 36.8

Excellent career teaching ratings 69.1

Teaching award recipient 38.2

Career research productivity

>5 refereed journal articles 67.6 >5 nonrefereed articles 39.4

≥1 book or book supplements 2.6

Research award recipient 23.2

Service activity

Above-average service providers 87.5

Note.Non-tenured tenure-track faculty members comprised 33.16% of the respondents. All percentages are rounded, and non-response percentages are not shown.

and nontenured tenure-track faculty. A mean rating score was calculated for each of the issues for both groups, these mean rating responses were compared, and an I computed an F

statistic (p<.05). The statistically significant mean ratings

of tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty were analyzed and the overall results are presented in Table 3. Variables with a statistically significant differences between the perception of tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty are identified by asterisks.

As noted in Table 3, tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty mean ratings differed for only 9 of the 20 tenure issues. In the previous study, significant differences existed for 13 of these tenure issues. Once again, the vast majority of faculty surveyed believed that tenure is necessary for per-sonal faculty security. Furthermore, tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty members at AACSB-accredited colleges were even more adamant in their need for tenure than they were previously (Premeaux & Mondy, 2002). Tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty members now appeared to agree that traditional tenure is essential and should remain

124 S. R. PREMEAUX

TABLE 3

Summary of Responses Regarding Various Tenure Issues: Tenured Versus Nontenured Tenure-Track Professors

Statement regarding tenure TenuredM(n=1058) NontenuredM(n=525) PR>F

Tenure is necessary for personal faculty security. 4.18 4.69a .0001

Necessity and modification of tenure.

Academic freedom cannot be secure without tenure. 3.91 4.64a .0004

Tenure is over applied, meaning too many faculty are tenured at most universities. 3.10 3.12 .8936

Tenure is necessary. 4.36 4.45 .6314

Tenure should be eliminated. 1.12 1.14 .2819

Tenure should be modified. 2.71 2.93 .4826

Tenure should be granted for only 20 years. 1.37 1.42 .9527

Tenure should be granted for only 25 years. 1.40 1.44 .5469

Tenure should be periodically evaluated rather than being a lifetime guarantee. 2.71 2.91 .7651

Teaching

Tenure helps promote teaching excellence. 2.98a 2.03 .0115

Tenure hinders teaching excellence. 2.18 3.21a .0268

Teaching is afforded too much importance. 1.32 1.38 .7549

The longer a person has been tenured the less effective he or she will be as a teacher. 2.02 3.59a .0146

Research

Research is afforded too much importance. 3.14 4.08a .0162

Tenure helps promote research excellence. 3.27a 2.12 .0197

The longer a person has been tenured the less effective he or she will be as a researcher. 2.26 3.91a .0341

Tenure hinders research excellence. 1.94 3.86a .0243

Service

Tenure helps promote service productivity. 2.79 2.86 .6389

Tenure hinders service productivity. 2.37 2.41 .3486

The longer a person has been tenured the less effective he or she will be at providing service. 2.19 2.21 .7984

Note. Responses were given on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (complete disagreement) to 5 (complete agreement). PR=probability.

aSignificant difference between means; PR>F value is less than the critical value of .05.

basically unchanged. This is a dramatic shift from the previ-ous investigation where significant differences existed, with nontenured tenure-track faculty generally agreeing that tra-ditionally applied tenure needed modification. Nontenured tenure-track faculty believed even more strongly than tenured faculty that traditionally applied tenure is necessary for per-sonal faculty security.

Necessity and Modification of Tenure

Significant differences exist between the perceptions of tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty with regard to the overall necessity and possible modification of tenure for only one of the eight tenure-related factors, down from five significant differences in 2001. The nontenured tenure-track faculty were in much stronger agreement that academic free-dom cannot be secure without tenure. In relation to the aca-demic freedom issue, a significant difference exists between tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty. It may be that the nontenured tenure-track faculty are more closely scruti-nized than tenured faculty, and therefore feel that their aca-demic freedom is threatened. In the previous investigation, nontenured tenure-track faculty agreed that tenure was over-applied, but presently both groups only moderately agreed that this is the case. Possibly, nontenured tenure-track faculty now want tenure to be applied more, so they have a greater

opportunity to earn tenure. In fact, both groups tended to have similar opinions regarding these tenure issues, which is a major shift from 2001.

Both groups now agreed, and are more adamant, that tenure is necessary. To an even greater degree than in 2001, both groups agreed that (a) “tenure shouldnotbe eliminated,” (b) “tenure shouldnotbe granted for only 20 years,” and (c) “tenure shouldnotbe granted for only 25 years.” Apparently, both groups feel even more strongly now that traditional tenure is necessary and should be a lifetime guarantee, rather than subject to periodic review. Even more so than in the pre-vious investigation, both groups embrace traditional tenure, with nontenured tenure-track faculty perspectives changing dramatically toward embracing traditional tenure, rather than modifying it.

Mission Achievement: Tenure’s Impact on Teaching, Research, and Service

Tenure’s value to its stakeholders can be judged by its impact on teaching, research, and service. The increased support for traditional tenure from both groups may result from faculty members wanting the personal security that tenure provides. However, the broader question is, does tra-ditionally applied tenure positively impact organizational performance? According to some, tenure’s value should be a function of promoting teaching, research, and service

excellence (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business [AACSB], 1994). Critics contend that “faculty members must behave less like independent contractors. .. and more like owner/managers. .. whose fortunes are tied to its success or failures (AACSB, p. 2). Hamilton (2007) countered that “our work as individual professors requires a high degree of autonomy” (p. 28).

Basically, tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty presently believe that tenure is necessary and that it should not be eliminated or modified. In a major shift from 2001, both groups believed in tenure’s necessity, and even non-tenured tenure-track faculty were no longer very flexible in terms of tenure modification and the need for periodic re-views. Based on these perceptions it may be quite difficult to modify tenure regardless of its impact on organizational performance.

Teaching

Tenured faculty moderately agreed that tenure helps pro-mote teaching excellence, but nontenured tenure-track fac-ulty disagreed. Significant differences also exist with regard to tenure hindering teaching excellence, with tenured faculty disagreeing and nontenured tenure-track faculty moderately agreeing. Even more so than in 2001, both groups agreed that teaching is not afforded too much importance. Finally, significant differences exist between tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty, with tenured faculty disagreeing and nontenured tenure-track faculty agreeing that the longer a person is tenured the less effective he or she is as a teacher. This raises the question as to whether longevity results in professors with greater teaching expertise, or does it simply facilitate less effective instruction?

Even more so than in 2001, both groups agreed that teaching is extremely important, even more important than research. Possibly, tenure permits less effective teaching because many universities tenure professors who are only marginal teachers, but who are somewhat prolific researchers. Additionally, in numerous studies the correlation between good teaching and strong research is either nonexistent, or in a minority of cases, only slightly positive (Felder, 1994). Possibly, the problem in business schools is granting tenure more on the basis of research productivity, than on demon-strated teaching excellence. Although both groups agreed that teaching is not afforded too much importance, they dis-agreed on the other three teaching-related issues even more so than in 2001.

Research

Even though the mission at many AACSB-accredited schools lists the importance of research as second to teaching, in reality “the present [tenure] system favors those who publish over those who shine in the classroom. .. and the rewards for excellence in scholarship are infinitely more plentiful than the rewards for excellence in teaching” (Worth, 1999, p. 1).

Basically, at many schools tenure decisions do not consider research, teaching, and service equally, and often research is the more important factor. Although the formula most often mentioned is 40%/40%/20% (research/teaching/service), in reality it is more like 90%/5%/5% (research/teaching/service; Worth, 1999).”

Many empirical studies have sought to explore and quan-tify the relationship between teaching and research. The re-sults have been remarkably consistent and offer evidence that teaching and research are separate activities, independent of each other. The relationship is not a negative one, in that good researchers are not automatically poor teachers, and good teachers are not automatically poor researchers, but the relationship is not positive, either.

However, undergraduate and graduate students associate more benefits than disadvantages with faculty research. Gen-erally, students agreed that knowledge currency, credibility, competence in supervision, enthusiasm, and motivation are enhanced by faculty research activity.

Significant differences exist for all four research issues, with both groups agreeing that research is afforded too much importance. However, tenured faculty only moderately agreed, whereas nontenured tenure-track faculty agreed more strongly. Tenured faculty moderately agreed that tenure helps promote research excellence, but the nontenured tenure-track group disagreed. Significant differences also exist regard-ing tenure’s duration and research effectiveness. Nontenured tenure-track faculty members agreed that the longer a person has been tenured, the less effective he or she is as a researcher; but tenured faculty disagreed. There are indications that fac-tors such as promotion and compensation may be better in-dicators regarding research productivity than tenure (Lazear, 2001; Neumann, 1979).

Obviously, once tenure is granted the employment secu-rity gained reduces the pressure to publish, and therefore, faculty may be less motivated to do research. Outside of aca-demics, job performance for those with less tenure seems to be better than for those with more tenure, and that may also be the case in the academic community (Moser & Galais, 2007). Finally, nontenured tenure-track faculty agreed that tenure hinders research excellence, but tenured faculty dis-agreed. Basically, the pressure to publish is much greater on nontenured tenure-track faculty who are working to earn tenure (Striver, 2006). Both groups disagreed on the four research-related issues even more so than in 2001.

Service

Service is normally the third and least important component of a business school’s mission. As in 2001, there were no sig-nificant perceptual differences regarding any of the service factors. Basically, both groups somewhat agreed that tenure helps promote service productivity, disagreed that tenure hin-ders service productivity, and disagreed that the longer an individual is tenured the less effective that individual is at

126 S. R. PREMEAUX

providing service. Overall, faculty opinions regarding tenure’s impact on service have changed very little since 2001.

Overall, tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty had several different perceptions regarding tenure’s impact on teaching and research. Generally, the level of disagreement between the groups regarding teaching and research has in-creased since 2001. However, tenured and nontenured tenure-track faculty members agreed that academic freedom cannot be secure without tenure. In fact, support among the non-tenured tenure-track faculty for an overhaul of traditional tenure has fallen rather dramatically since 2001. At present, there is much less support for tenure modification and peri-odic reviews than in 2001, despite the perceptions by many nontenured tenure-track faculty that tenure negatively im-pacts teaching and research.

Summary and Implications

Although neither group wanted to eliminate tenure in 2001, a major shift occurred in the attitudes of nontenured tenure-track faculty regarding the appropriateness of traditional tenure. At present, tenured and nontenured tenure-track fac-ulty want to perpetuate many aspects of traditional tenure. In the previous investigation, nontenured tenure-track faculty were much more in favor of changing traditionally applied tenure. Despite the present acknowledgement by nontenured tenure-track faculty that tenure is problematic, as it relates to teaching and research, they now view traditional tenure much more positively. Possibly this is the result of the changing dy-namics of universities’ faculties with the move toward more part-time and non-tenure-track hiring (Budd, 2006). Non-tenured faculty may view the present hiring climate as an-titenure, and therefore want to attain traditional tenure before the hostility increases.

Even though a few schools are trying to assist faculty in securing tenure, the process is not similar to earning tradi-tional tenure. Yale University now has a mentoring process to help guide faculty toward a tenure track, but the tenure process can begin as late as the eighth year of employment (Millman, 2007). Princeton University is trying to assist par-ents, and particularly women, in attaining tenure by allowing extra time based on the number of children they have (Bhat-tacharjee, 2005). However, this approach, similar to the Yale process, actually adds more time to the tenure process rather than making it more expedient.

Nontenured tenure-track faculty tended to agree that tra-ditionally applied tenure can be detrimental to teaching and research, but both groups perceived tenure’s protection as extremely desirable. Advocates have stated that protecting faculty with tenure is more important than getting rid of poor performing faculty. Tenure protects ideas and prevents narrow-minded administrators from keeping only those fac-ulty members who think similar to how they do. But even

advocates of tenure tend to agree that there is a need for a better evaluation process of faculty at the probationary level. If tenure means lifetime employment, then make sure that the right people are tenured (Moore, 2008).

Tenure has been described as a nerve-racking five years, but with that nerve-racking experience comes the reward of lifetime employment security that faculty desperately want (Striver, 2006). Because of the desire for personal security it appears that neither group will support even a minor over-haul of tenure. Subsequently, even incremental steps to mod-ify tenure may be quite difficult. Apparently, many faculty members, tenured and nontenured tenure track, believe that their personal security is threatened by tenure changes.

Most schools offer tenure, and not doing so would create a significant recruiting disadvantage; evidently most faculty desire traditionally applied tenure. Even though nontenured tenure-track faculty still view tenure as negatively impacting teaching and research, they, just as the tenured faculty do, now embrace traditional tenure. Basically, changes in tenure will be difficult to enact because the majority of both groups now agree that traditional tenure is necessary. Overall, much less faculty support now exists for modifying tenure than in 2001.

REFERENCES

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. (1994). Volume is turning up on tenure question.AACSB Newsline,24(Winter), 1–6. Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. (2005).

Member-ship directory. Tampa, FL: Author.

Bhattacharjee, Y. (2005). Princeton resets family-friendly tenure clock. Sci-ence,309, 308–310.

Buck, J. L. (2006). Why ask if tenure is necessary?Behavioral & Brain Sciences,29, 570.

Budd, J. M. (2006). Faculty publishing productivity: Comparisons over time. College & Research Libraries,67, 230–239.

Ceci, S. J., Williams, W. M., & Mueller-Johnson, K. (2006). Is tenure jus-tified? An experimental study of faculty beliefs about tenure, promotion, and academic freedom.Behavioral & Brain Sciences,29, 553–569. Chen, Y., Gupta, A., & Hoshower, L. (2006). Factors that motivate business

faculty to conduct research: An expectancy theory analysis.Journal of Education for Business,81, 179–189.

Defleur, M. L. (2007). What is tenure and how do I get it? Communication Education,56, 106–112.

Editorial Board. (2008, April 11). Professor tenure worth the cost.The Daily Cardinal, p. 3.

Felder, R. M. (1994). The myth of the superhuman professor.Journal of Engineering Education 82, 105–110.

Finkin, M. W. (1996, December 3). Scrapping tenure would raise costs.USA Today,14.

Fogg, P. (2005). The state of tenure.Chronicle of Higher Education,51, A15–A16.

Hamilton, N. W. (2007). Faculty autonomy and obligation.Academe,93, 36–42.

Hughey, A. (2009, March 17). Tenure secures academic freedom. Courier-Journal, p. 17.

Isfahani, N. (1998). SPALR Student Paper: The Debate over Tenure.Review of Public Personnel Administration,18, 80–86.

Lataif, L. E. (1998). Lifetime tenure: A working alternative.Selections,15, 1–6.

Lazear, E. P. (2001).The Peter Principle: Promotions and declining pro-ductivity. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. w8094.

Lederman, D. (2006, April 6). Blame it on the faculty.Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved from http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2006/04/06/costs MacLeod, W. B. (2006). Tenure is justifiable.Behavioral & Brain Sciences,

29, 581–583.

Margolin, J. B. (2007). Battle against tenure is ill-informed, perpetual. Ed-ucation Week,26, 34.

McGinn, D., & Blake, H. (2000, November 13). A Ph.D. hits the road. Newsweek,70.

Millman, S. (2007). Yale to overhaul tenure process.Chronicle of Higher Education,53, A14.

Moore, M. (2008, September 11). Teacher tenure protects ideas. Savan-nah Morning News. Received from http://savanSavan-nahnow.com/michael- http://savannahnow.com/michael-moore/2008–09–11/moore-teacher-tenure-protects-ideas

Moser, K., & Galais, N. (2007). Self-monitoring and job performance: The moderating role of tenure.International Journal of Selection & Assess-ment,15, 83–93.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2003).Staff in postsecondary insti-tutions, fall 2001, and salaries of full-time instructional staff, 2001–2002. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Neumann, Y. (1979). Research productivity of tenured and non-tenured faculty in U.S. universities: A comparative study of four fields and policy implications. Journal of Educational Administration, 17, 92– 101.

Pearce, J. A. (1999). Faculty survey on business education reform.The Academy of Management Executive,13, 105–109.

Perley, J. E. (1998). Reflections on tenure.Sociological Perspectives,41, 723–729.

Premeaux, S. R., & Mondy, R. W. (2002). Tenure: Tenured and non-tenured tenure-track faculty perspectives.Journal of Education for Business,77, 335–339.

Ryman, A. (2008, June 29). Universities cutting back on tenure or teachers. The Arizona Public, p. 2.

Smith, Z. (2000, June 21). Study cites drop in tenured faculty.University Wire, p. 1.

Strauss, V. (2000, May 14). The trouble with tenure; while professors still crave it, many believe the lifetime appointment is dying—and not for the reasons you think.The Washington Post, W16.

Striver, J. (2006). I’ll bring the salad.Chronicle of Higher Education,52, C3.

Worth, R. (1999, May). The velvet prison.Washington Monthly,31(5), 1.