Sri Lankan Blue Swimming Crab

Fishery Assessment

Final Report

by

Dr. Steve Creech

Submitted to

Co-financed by

National Fisheries Institute

Crab Council

on

25

thNovember 2013

List of Abbreviations

BSC Blue Swimming Crab (Portunus pelagicus) CAB Conformity Assessment Body (MSC)

CASS Conservation Alliance for Sustainable Seafood CEPA Centre for Poverty Analysis

CPUE Catch Per Unit Effort CSO Civil Society Organisation CW Carapace Width

DCD Department of Cooperative Development DFAR Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources DFF Dist i t Fishe e s Fede atio

DFO District Fisheries Office EPF E plo ees P o ide t Fu d ETF E plo ees T ust Fu d

ETP Endangered, Threatened and Protected

FAO UN Food & Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations FCS Fishe e s Coope ati e “o iet

FCSU Fishe e s Coope ati e “o iet U io FI Fisheries Inspector

FIP Fishery Improvement Project

g grams

GOI Government of India GOSL Government of Sri Lanka GPS Geographic Positioning System

HACCP Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points

ILO UN International Labour Organization of the United Nations IMBL International Maritime Boundary Line

IOM International Organisation for Migration IUU Illegal Unregulated Unreported

JAF Jaffna District KIL Kilinochchi District

l litre

lb Imperial Pound

LEED Local Economic Empowerment through Enterprise Development LKR Sri Lankan Rupee

LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam MAN Mannar District

MFAR Ministry of Fisheries & Aquatic Resource MSC Marine Stewardship Council

N North

NAFSO National Fisheries Solidarity Organisation NAQDA National Aquaculture Development Authority NARA National Aquatic Resources Research Agency NEM North East Monsoon

NFI CC National Fisheries Institute Crab Council NP Northern Province

OSH Occupational Safety & Health PUT Puttalam District

RFO ‘u al Fishe e s O ga isatio SC Steering Committee (FIP)

SEASL “eafood E po te s Asso iatio of “ i La ka SFP Sustainable Fisheries Partnership

SLBSC Sri Lankan Blue Swimming Crab (Portunus pelagicus) SRL Sri Lanka

t Metric Tonne TOR Terms of Reference

UNDP United Nations Development Programme UOJ University of Jaffna

US$ American Dollar

W Weight

WU Wyamba University

List of Tables

Table 1 Evaluation matrix for the assessment of the SLBSC fishery

Table 2 Summary of interviews conducted with participants during the fishery assessment Table 3 The type and estimated number of fishing craft engaged in the SLBSC Fishery, by district Table 4 Summary of the Relationship between Mesh Size, Crab Size and Markets

Table 5 Key Seafood Companies Purchasing, Processing and Exporting SLBSC

Table 6 Grading Systems, Weight and Prices Paid for SLBSC in Operation during the Survey Table 7 Export Destinations for Sri Lankan Crab Products January 2011 to March 2012

Table 8 Marine fauna and flora observed or reportedly caught in bottom-set gill nets, together with observations on endangered, threatened and protected species.

Table 9 Estimated incremental losses incurred by catching smaller and smaller sized crabs Table 10 Summary of the MSC Guidepost Scores for the SLBSC Fishery

List of Figures

Figure 1 Size and weight relationship for SLBSC in Pallikuda (Kalpitiya) and Mandaitivu (Jaffna) Figure 2 Annual Sri Lankan crab production for all crab varieties

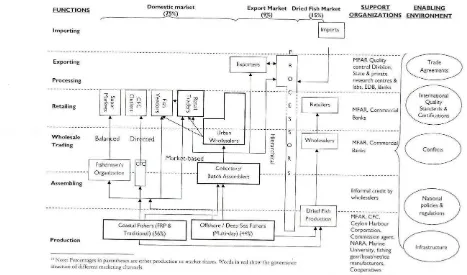

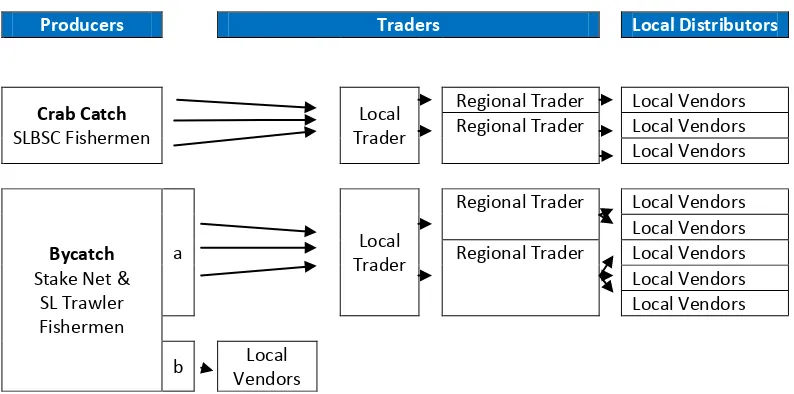

Figure 3 Comparative increases in crab production in four districts since 2009 Figure 4 Export destinations and value (LKRs) of crab exports 1990 to 2011 Figure 5 Sri Lanka marine fisheries value chain map (USAID 2008)

Figure 5 Schematic representations of supply chains for SLBSCs

Figure 6 Relative Contributions of Crab Products to Exports, by Weight (kg) and Value (LKR) Figure 7 Relative Contributions of Crab Export Products, by Weight (kg) and Value (LKR) Figure 8 Estimated Increase in Fishery Income by Catching Larger and Large Sized Crabs

List of Annexes

Anne A Comparative analysis of the current status of FIP for four swimming crab fisheries in Indonesia, Philippines, Mexico and Russia

Annex B Co sulta t s Te s of ‘efe e e

Annex C Main assessment criteria and sub criteria used during the field survey

Annex D List of the scientific papers, technical reports and guidelines reviewed during the assignment Annex E Co sulta t s completed work schedule for the assessment of the SLBSC Fishery

Annex F List of the agencies, organisations and individuals who generously contributed information, comments and suggestions to improve the SLBSC Fishery

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ... 1

I. Introduction ... 4

II. Scope of Work ... 6

III. Fishery Assessment Methodology & Criteria ... 7

IV. Implementation & Data Analysis ... 8

V. Key Findings ... 10

a. Biology of the Fishery ... 10

b. Physical Profile ... 12

c. Social Profile 21

d. Economic Profile ... 24

e. The Ecology of the SLBSC Fishery ... 33

f. Management of the Fishery ... 36

VI. Conclusions ... 43

Principle 1: Biological Status of the Fishery ... 44

1.1 SLBSC Resource ... 44

1.2 SLBSC Management ... 46

Principle 2: Ecological Impacts of the Fishery ... 49

2.1 Retained Bycatch Species ... 49

2.2 Discarded Bycatch Species ... 50

2.3 ETP Bycatch Species ... 52

2.4 Marine Habitats ... 53

2.5 Marine Ecosystems ... 55

Principle 3: Management of Fishery ... 57

3.1 Governance & Policy ... 57

3.2 Fishery Specific Management System ... 60

VI. Recommendations ... 62

Recommendations to improve the biological status of the fishery ... 62

Recommendations to improve / reduce the ecological impacts of the fishery ... 63

1

Executive Summary

1) The “eafood E po te s Asso iatio of “ i La ka “EA“L ep ese ts and promotes the interests of Sri Lankan companies engaged in the export of seafood products from Sri Lanka. The SEASL provides a common platform for Sri Lankan seafood companies to discuss challenges and concerns affecting seafood exports, as well as issues affecting the fisheries industry as a whole in Sri Lanka.

2) In May 2013, the SEASL convened a meeting of participants engaged in the Sri Lankan blue swimming crab (SLBSC) fishery in Negombo, so explore ways to improve the fishery. The Negombo meeting was convened with the support of the National Fisheries Institute Crab Council (NFI CC). At the end of the meeting the SEASL took a decision to initiate a Fisheries Improvement Project (FIP) for the SLBSC fishery, to improve the fishery in accordance with the principles set out by the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP).

3) The aim of a FIP is to bring together all those associated to a fishery i.e., fishing communities, traders, seafood companies, regulators, scientists and civil society organisations (CSO), as well as international importers and distributors, to create and implement a local plan that will improve the economic, social and ecological sustainability of a fishery. A key step in the process of initiating a FIP is undertaking an assessment of the fishery.

4) The assessment of the SLBSC fishery was conducted between August and November 2013. The assessment commenced with a review of technical reports, scientific papers and guidelines pertaining to blue swimming crabs (BSC) in general. The processes and frameworks associated with the design and development of various FIPs, including other crab FIPs were also reviewed, along with the Marine “te a dship Cou il s principles, criteria and principal indicators for sustainable fisheries.

5) A field survey of the SLBSC fishery, which is located off the north western and northern coast of Sri Lanka, was completed over a period of six weeks beginning from the 1st August 2013. The last interviews with participants in the fishery were conducted with a CSO in Colombo on 16th September. A total of 36 interviews were conducted with 112 individuals associated with the SLBSC fishery in five coastal districts, as well as in the capital Colombo. 11% of the participants in the field survey were women.

6) The experiences, knowledge, opinions and comments gathered from key participants in the SLBSC fishery form the basis of the SLBSC fishery assessment report. The findings of the assessment indicate that the “LB“C fishe is likel to fail to eet the e ui e e ts e essa to pass out of M“C s performance indicators for sustainable fisheries. The assessment suggests that the fishery may pass seven performance indicators, but would subsequently need to meet conditions applied by the independent MSC assessor.

7) The principal deficiencies in terms of achieving sustainable management of the fishery relate to principles 1 and 2. The fishery is likely to fail all seven performance indicators associated the biological status of the SLBSC resource. The fishery is likely to fail 13 of the 15 performance indicators associated the ecological impacts of the fishery (Principle 2). A summary of the MSC Guidepost Scores for the SLBSC fishery is given overleaf.

2

Summary of the MSC Guidepost Scores for the SLBSC Fishery

MSC Fishery Assessment

Principles, Criteria & Performance Indicators Fishery Assessment

Guidepost Score Result

Principle 1 Biological Status of the Fishery 1.1 SLBSC Resource

1.1.1 Stock Status SG <60 FAIL 1.1.2 Reference Points SG <60 FAIL

1.1.3 Stock Rebuilding Plan SG <60 FAIL

1.2 SLBSC Management

1.2.1 Harvest Strategy SG <60 FAIL

1.2.2 Harvest Control Rules & Tools SG <60 FAIL 1.2.3 Harvest Strategy: Information & Monitoring SG <60 FAIL

1.2.4 Assessment of Stock Status SG <60 FAIL

Principle 2 Ecological Impacts of the Fishery 2.1 Bycatch: Retained Species

2.1.1 Status SG <60 FAIL

2.2.2 Management Strategy SG <60 FAIL

2.2.3 Information / Monitoring SG <60 FAIL

2.2 Bycatch: Discarded Species

2.2.1 Status SG <60 FAIL

2.2.2 Management Strategy SG <60 FAIL

2.2.3 Information / Monitoring SG <60 FAIL

2.3 Bycatch: ETP Species

2.3.1 Status SG <60 FAIL

2.3.2 Management Strategy SG <60 FAIL

2.3.3 Information / Monitoring SG <60 FAIL

2.4 Marine Habitats

2.4.1 Status SG <60 FAIL

2.4.2 Management Strategy SG <60 FAIL

2.4.3 Information / Monitoring SG <60 FAIL

2.5 Marine Ecosystems

2.5.1 Status SG 60 PASS with conditions

2.5.2 Management Strategy SG <60 FAIL

2.5.3 Information / Monitoring SG 60 PASS with conditions

Principle 3Management of Fishery 3.1 Governance & Policy

3.1.1 Legal / Customary Framework SG 70 PASS with conditions 3.1.2 Consultation, Roles & Responsibilities SG 60 PASS with conditions

3.1.3 Long Term Objectives SG 60 PASS with conditions

3.1.4 Incentives for Sustainable Fishing SG <60 FAIL

3.2 Fishery Specific Management System

3.2.1 Fishery Specific Objectives SG <60 FAIL

3.2.2 Decision Making Processes SG 60 PASS with conditions 3.3.3 Compliance & Enforcement SG 70 PASS with conditions

3.3.4 Research Plans SG <60 FAIL

3.3.5 Management Performance Evaluation SG <60 FAIL

Recommendations to improve the biological status of the fishery

I. Regular monthly monitoring of CW and W should commence from two or more locations by a recognised government agency / institution. Field data should be analysed together with

p odu tio data gathe ed seafood e po te s pu hasi g & p o essi g “LB“C. II. Discussions should be held with the Department of Customs to explore the possibility of

disaggregating crab export data for SLBSC.

III. A research project should be commissioned to investigate the population biology of the SLBSC IV. A study should be commissioned to investigate the effectiveness of measures promoted to

3 V. A study should be commissioned to investigate the selectivity of bottom-set gill nylon gill nets,

with a view to establishing a minimum mesh size for the SLBSC fishery

VI. The GOSL should be lobbied and there should be advocacy among fishing communities, against the use of illegal monofilament nets.

VII. There should be continued support for and promotion of measures to mitigation or reduce the harvesting of ovigerous females

VIII. A regulation should be introduced for the SLBSC fishery

IX. The GOSL should continue to be lobbied and there should be continued advocacy with SLBSC fishermen to stop illegal trawling by IND and SRL trawlers

X. Technical and financial assistance should be provided to DFAR / MFAR to improve the collection and analysis of field data and information to monitor the exploitation of Sri Lankan marine resources.

XI. The assessment report and recommendations should be validated by an MSC approved independent conformity assessment body (CAB)

XII. Preparations should be made to undertake or commission an assessment of the status of the SLBSC stock after the improvements to the SLBSC fishery outlined in the assessment report have been satisfactorily achieved

Recommendations to improve / reduce the ecological impacts of the fishery

XIII. A study should be commissioned to further investigate the nature and quantity of the bycatch (retained, discarded and ETP species) from the SLBSC fishery, with emphasis on the role of mesh size on bycatch composition

XIV. A study should be commissioned to further investigate the interaction between the SLBSC fishery and key marine habitats in the vicinity of the fishery.

Recommendations to improve management of fishery

XV. A Steering Committee (SC) for the SLBSC FIP (see Annex G) should be established comprising representatives of the fishing communities, seafood companies and government authorities, to facilitate dialogue and decision making between participants in the SLBSC fishery. The roles and responsibilities of participants should be clearly defined.

XVI. Long term objectives - resource, ecological, social and economic and management - for the SLBSC fishery should be reviewed, discussed and agreed.

XVII. Key incentives for sustainable exploitation of the SLBSC resource should be formulated, discussed, agreed and promoted

XVIII. Specific policy objectives for the SLBSC fishery Committee should be formulated, discussed, agreed and promoted

XIX. The GOSL should continue to be lobbied and there should be further advocacy to ensure better compliance with the regulations that that govern the exploitation and management of the SLBSC fishery, including stronger enforcement of regulations pertaining to the use of illegal

monofilament nets and trawling by Indian and Sri Lankan trawlers

XX. Financial support should be provided through local universities and to the NARA to conduct research into key aspects of the SLBSC fishery

XXI. A mechanism to monitor and evaluate the performance of the SLBSC fishery management system should be developed

XXII. A stud should e u de take to assess the e te t of seafood o pa ies o plia e ith internationally recognised Decent Work Standards.

XXIII. A study should be undertaken to assess the feasibility and constraints pertaining to promoting producer organisation engagement in marketing / processing of SLBSC.

4

I.

Introduction

The Sri Lanka Seafood Exporters’ Association of Sri Lanka

9) The “eafood E po te s Asso iatio of “ i La ka “EA“L as esta lished to ep ese t a d promote the interests of Sri Lankan companies engaged in the export of seafood products from Sri Lanka. The SEASL provides a common platform for Sri Lankan seafood companies to discuss challenges and concerns affecting seafood exports, as well as issues affecting the fisheries industry as a whole in Sri Lanka.

10) The SEASL acts as an important focal point for engagement between seafood companies and the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL). The SEASL lobbies and advises the government on policy and practices related to seafood exports, including inspection, licensing and certification of seafood products. The SEASL is also a forum for dialogue within the seafood community in Sri Lankan and between the Sri Lankan seafood sector and the international seafood community.

11) The “EA“L s goal is to ensure the long term economic, social and environmental sustainability of the seafood sector in Sri Lanka. To achieve this goal, the SEASL and its member organisations work in close collaboration with producers and suppliers, as well as with the agencies and authorities of the GOSL. The “EA“L p o otes a d seeks to i p o e the sustai a le e ploitatio a d a age e t of “ i La ka s marine resources.

Fishery Improvement Projects

12) The aim of a fishery improvement project (FIP) is to bring together all those associated to a particular fishery i.e., fishing communities, traders, seafood companies, regulators, scientists, civil society organisations (CSO) and foreign importers and distributors, to create and implement a local plan that will improve the economic, social and ecological sustainability of a fishery.

13) The driving force behind the desire to improve local, national and international fisheries is the increasing glo al o e a out the lo g te futu e of fish sto ks. O e % of the o ld s fish stock are either fully or over exploited. When fish stock crash, everyone associated with the fishery is affected. The Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP1), a seafood business orientated non government organisation based in the United States of America, is at the forefront of encouraging FIPs.

14) The SFP brings together representatives of fishing communities, national and international seafood companies, government authorities and researchers to generate and share information that can be used to improve local, national and international fisheries.

15) There are now more than 40 FIPs in operation around the world, four of which, in Russia, Mexico, Philippines and Indonesia, are for swimming crab fisheries. A comparative analysis of these four swimming crab FIPs, is presented in Annex A.

16) A single FIP is under implementation in Sri Lanka, for Sri Lankan yellowfin (Thunus albacare) and bigeye (T. obesus) tuna (see http://www.seasl.lk/index.php/sustainablefisheries/sltfip), which is managed by the SEASL.

1

5 A FIP for the Sri Lankan Blue Swimming Crab

17) The decision to initiate a FIP for the Sri Lankan blue swimming crab (SLBSC) was made by the SEASL after receiving requests from representatives of Sri Lankan seafood companies, government authorities, researchers and civil society organisations associated with the SLBSC fishery in the north of Sri Lanka. A meeting of seafood companies, agencies and individuals associated with the SLBSC fishery was convened by the SEASL in Negombo, in May 2013, with the support of the National Fisheries Institute Crab Council (NFI CC).

18) The NFI CC is an American CSO that comprises representatives from the leading importers and distributors of blue swimming crab in the USA. The NFI CC is dedicated to improving standards and p a ti es that ill e ha e the seafood i dust s a age e t of lue s i i g a fishe ies a ou d the world: based on sound ecological and economic principles.

About Blue Swimming Crabs

19) The blue swimming crab (BSC) Portunus pelagicus (see image below) is a tropical marine crustacean that occurs in large shoals in shallow coastal water overlying sandy or muddy substrates. It is common throughout the Indo-pacific region, from the eastern coast of Africa, throughout South Asia, Southeast Asia and Australia, to the western coast of North and South America. Populations of BSC are also found in the Mediterranean Sea.

20) The lifecycle of the BSC is short: crabs typically live for only three to four years (Dineshababu et al., 2008). Adults reach a maximum size of around 190mm (carapace width) and a maximum weight of around 550g (Sukumaran & Neelakantan 1996). Female crabs become sexually mature towards the end of their first year, at sizes ranging from 33mm to 177mm (body weight ≈ g to 150g) (Kamrani et al., 2010). Female crabs produce between 0.10 million to 1.1 million eggs at a single spawning, depending on their size (REF). Larger female crabs produce proportionally more eggs than smaller female crabs (Kumar et al., 1999)). Females spawn once a year. Female crabs brood their eggs, incubating the eggs for five to seven days before the larvae hatch.

21) BSC populations typically have a distinct, peak spawning season. In warmer climates a small number of individual spawn throughout the year. After hatching and joining the plankton, BSC larvae drift with the wind and tides. BSC larvae undergo a series of morphological changes over a period of 21 to 25 days before they become juvenile crabs, measuring 15 mm – 35 mm (Anand & Soundarapandian, 2011). SLBSC are voracious hunters and scavengers. BSC eat small shrimps and other crabs (including other BSC), finfish, cuttlefish, shellfish, squid and worms, as well as seaweed and dead and decaying matter (Menon, 1952).

22) The growth of BSC is closely determined by water temperature. In warmer climates BSC grow quickly reaching close to their maximum size and weight by the end of their second year. A variety of pelagic and benthic fish species including jacks and bream are known to prey on BSC populations.

6

II.

Scope of Work

23) The Scope of Work for the assessment of the SLBSC fishery off the northwest and northern coast of Sri Lanka, was set out in a contractual agreement signed between the between the Consultant and the SEASL on 1st August 2013 (see Annex B). The sub activities proposed in respect of the assessment included, but were not restricted to;

a) A review of other comparable FIPs worldwide

b) A review of secondary data pertaining the BSC fishery in Sri Lanka

c) The identification and collection of primary data from relevant stakeholders d) Drafting and finalising the fishery assessment report

24) The Scope of Work for the assessment was informed by the procedures and methods promoted by the SFP for the formulation of FIP2 and guided by the criteria endorsed by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) vis-a-vis the certification of sustainable fisheries3. The conclusions and recommendation set out in the first draft of the final report were therefore presented i a o da e ith the “FP s t o p i ipal components for fishery improvement i.e., FIP 4: measurable and positive social and economic changes and FIP 5: measurable and positive biological and ecological change. The sub activities identified by SFP under FIP 3.0 were assigned to the relevant FIP principal component.

25) Following a review of the first draft of the final fishery assessment report a d ha ges i the NFI CC s perspective on fishery assessment reporting, the NFI CC requested the SEASL and the Consultant to submit the final report in accordance with the M“C s Fishe “ta da d: P i iples a d C ite ia fo Sustainable Fishing. The conclusions and recommendations presented below are thus made in a o da e ith M“C s th ee o e p i iples i.e., biological status of the fishery; ecological impact of the fishery and management of the fishery), rather than in accordance with the “FP s t o p i ipal components for fishery improvement impact on the environment and fishery as originally agreed.

26) This report represents the first of a series of deliverables agreed in the aforementioned contract. Other deliverables that have been achieved during the course of the fishery assessment include:

a) A web page for the SLBSC FIP (http://www.seasl.lk/index.php/sustainablefisheries/slbscfip) b) A Scoping Document for the SLBSC FIP

c) A FIP Development Plan (2013 – 2014)

d) A FIP Implementation Plan and budget for the SLBSC FIP (2013 – 2016)

e) A Logic Model for the SLBSC FIP, based on the Development Plan and Implementation Plan

2

www.sustainablefish.org 3

7

III.

Fishery Assessment Methodology & Criteria

27) The methodology adopted for the assessment of the SLBSC fishery was based on the collection and analysis of both quantitative data and qualitative information. The methodology sought to gather quantitative data from secondary sources (i.e., published and unpublished reports and studies), while the sources of qualitative information were gathered from participants in the SLBSC fishery. Qualitative information was collected by means of semi structured interviews (see images below), the duration of which was designed not to last more than 45 minutes.

28) Four main groups of participants were identified as forming the basis for the assessment, as follows:

a. producers(i.e., fishermen and women)

b. traders and seafood companies (i.e.,

local buyers and processors / exporters) c. regulators (i.e., government ministries, departments, agencies and authorities)

d. civil society (both national and

international organisations)

29) Four main criteria – biological, socio-economic, ecological and management - were delineated by the Consultant, following the guideli es set out the “FP s FIP p o ess and the MSCs Fishe “ta da d. These criteria were used as the basis for the assessment of the SLBSC fishery. Each criterion describes an aspect of the SLBSC fishery.

30) The biological aspects of the fishery evaluated included data and information pertaining to geographic range, population biology and reproductive biology. Socio-economic aspects of the fishery included location and seasonality of the fishery and landing centres; types of boats and gear; productivity; history, culture and social organisation, supply and value chain economic and the relative social and economic importance of the fishery. The assessment of ecological aspects of the fishery focused on the bycatch from the fishery (i.e., commercial / non commercial; retained / discarded and endangered, threatened and protected (ETP) species), as well as the habitat and ecosystem impacts of the fishery.

31) The last of the four evaluation criteria - fishery management - was designed to assess the nature, level and effectiveness of the management of the SLBSC fishery. The management of the fishery was assessed based on formal and informal data collection procedures; estimates of abundance; formal and informal (traditional) fishery management legislation, regulations and conventions; stock enhancement programmes; local compliance and effective of any such controls and the prevalence (if any) of illegal, unreported or unregulated (IUU) catch. A detailed description of sub questions explored during the course of the evaluation, for each of the four main assessment criteria, is presented in Annex C.

8

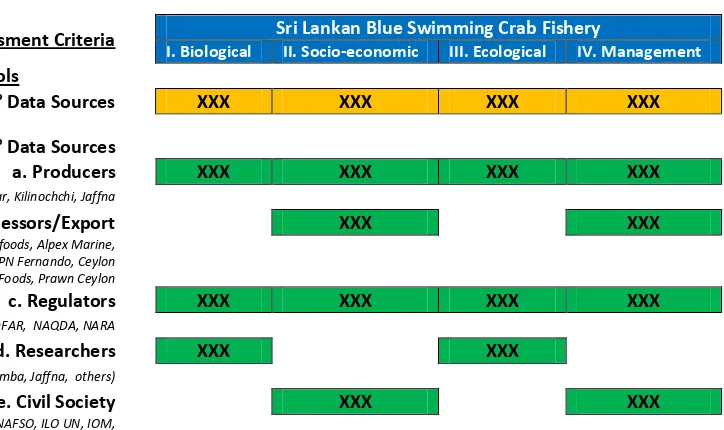

Table 1 Evaluation matrix for the assessment of the SLBSC fishery

Assessment Criteria Sri Lankan Blue Swimming Crab Fishery

I. Biological II. Socio-economic III. Ecological IV. Management Assessment Tools

2° Data Sources XXX XXX XXX XXX

1° Data Sources

a. Producers XXX XXX XXX XXX

Kalpitiya, Mannar, Kilinochchi, Jaffna

b. Trade/Processors/Export XXX XXX

SEASL, TSF, Phillipsfoods, Alpex Marine, Western Lanka, PN Fernando, Ceylon Foods, Prawn Ceylon

c. Regulators XXX XXX XXX XXX

MFAR, DFAR, NAQDA, NARA

d. Researchers XXX XXX

Universities (Wyamba, Jaffna, others)

e. Civil Society XXX XXX

CEPA, FAO UN, NAFSO, ILO UN, IOM, UNDP

IV. Implementation & Data Analysis

33) A number of scientific papers, technical reports and studies and guidelines pertaining to either BSC or FIPs and fishery management reviewed during the course of the assessment (see Annex D).

34) The field survey assessment of the SLBSC fishery off the north western and northern coast of Sri Lanka was completed by the Consultant over a period of six (6) weeks beginning on the 1st August 2013. The last interviews were conducted with CSO in Colombo on 16th September. The completed schedule of interviews in five districts and in Colombo with producers, processors, regulators and CSO is set out in Annex E. A list of the agencies, organisations, and individuals met by the Consultant during the course of the assessment is provided in Annex F.

35) A total of 36 interviews were conducted with 112 individuals associated with the SLBSC fishery during the course of the assessment (see Table 2). Twelve of the participants in the field survey were women (11%). Participants in the SLBSC fishery shared their experiences and knowledge of the fishery with the Consultant during the course of the field survey. Their opinions on the key initiatives necessary to improve the SLBSC fishery were also sought during the assessment.

36) Qualitative data collected during the course of the field survey was analysed by coding each observation and opinion. 47 sub codes were used by the Consultant to disaggregate the qualitative data, under each of the four principal assessment criteria. In addition to the four main assessment criteria, qualitative data des i i g espo de ts suggestio s to i p o e the “LB“C fishe as also a al sed odi g the suggestions. A summary of the sub codes used by the Consultant to analyse and interpret the qualitative data collected during the course of the field assessment is present in Table 3.

37) Once all the information collected had been coded, the information was sorted by sub code. The key fi di gs p ese ted i the follo i g se tio , a e ased o the Co sulta t s a al sis of the oded a d sorted data.

9 report. The final assessment report on the SLBSC fishery off the north western and northern coast of Sri Lanka was submitted to and approved by the SEASL on 23rd November 20134.

Table 2 Summary of interviews conducted with participants during the assessment

Interviews Target Achieved

Fishing Communities in 4 districts 7 8

Crab traders in 4 districts 4 3

Seafood Companies 3 7

DoFAR in 4 districts 4 4

NARA (Colombo / Kalpitiya) 1 1

Civil Society Organisations (CS) 2 3

Universities 2 1

Fishe e s Coope ati e “o iet U io s 0 4

District Fisheries Federations 0 4

Other 0 1

Totals 23 36

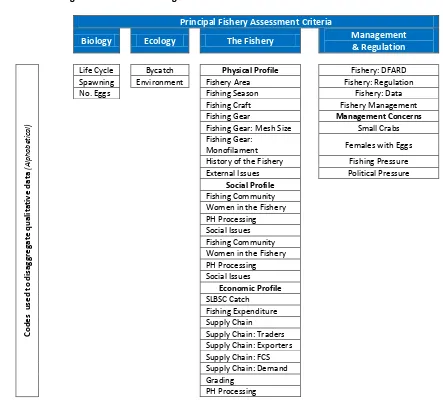

Table 3 Codes used to disaggregate qualitative data collected from producers, processors,

regulators and CSO with regard to each of the four main assessment criteria

Principal Fishery Assessment Criteria

Biology Ecology The Fishery Management

& Regulation

Life Cycle Bycatch Physical Profile Fishery: DFARD

Spawning Environment Fishery Area Fishery: Regulation

No. Eggs Fishing Season Fishery: Data

Fishing Craft Fishery Management

Fishing Gear Management Concerns

Fishing Gear: Mesh Size Small Crabs

Fishing Gear:

Monofilament Females with Eggs

History of the Fishery Fishing Pressure

External Issues Political Pressure

10

V.

Key Findings

a. Biology of the Fishery

39) Chit a adi elu s pape des i i g aspe ts of the fishery and species composition of edible crabs in Jaffna Lagoon (1993) is the only published record of the BSC in Sri Lanka. Two others Sri Lankan research papers (Sivanathnan, S., & de Croos M. D. S. T.; Nadaraja, T.) were in preparation at the time of the assessment. Neither paper was in available in draft form. None of these papers deal with aspects of the biology of the SLBSC. As noted by Jayamana very little scientific research has been undertaken on this species (Portunus Pelagicus – see right) in Sri Lanka (2011).

40) In contrast a number of papers have been published describing the biology of the BSC in South India. These include Prasad, R. R. & Tampi, P R S (1952) in the Palk Bay; P. T. Sarda off the coast of Calicut (1998); Dineshababu, A. P., et al (2008) off the southern Karnataka coast and Anand, T. & Soundarapandian, P. (2011) in the Palk Bay.

41) Aspects of the biology of the BSC off the south coast of India reported in these papers are consistent with the global research on the BSC described in the Introduction above. Accordingly, the lifecycle of the BSC in India is short: crabs typically live for three years. Adults reach a maximum size of around 170 mm for female carapace width (Dineshababu et al., 2008). Female crabs become sexually mature towards the end of their first year. Size at 50% maturity is 96 mm - carapace width (CW) - according to Dineshababu et al., (2008), while the majority of ovigerous females caught are between CW 115 mm and CW 159 mm (Prasad & Tampi 1952). Female crabs produce between 0.10 million to 0.90 million eggs at a single spawning (Anand & Soundarapandian 2011), depending on their size. Larger female crabs produce proportionally more eggs than smaller female crabs. Females spawn once a year. Larval duration is around 25 days (Anand & Soundarapandian 2011).

42) In Kalpitiya (Puttalam District), field evidence was advanced by fishing communities to suggest that two populations of SLBSC may be present, one located in the main body of Puttalam Lagoon and Dutch Bay and the other in the adjacent open sea (see map below). It was suggested that the two populations were separated due to environmental conditions including high salinities and temperatures experienced by SLBSC caught from Puttalam Lagoon and Dutch Bay. This argument was advanced to explain the relatively smaller size of SLBSC caught from the southern end of the lagoon, compared to the open sea.

11

Figure 1: Size and weight relationship for SLBSC in Pallikuda (Kalpitiya) and Mandaitivu (Jaffna)

44) SLBSC mature and begin to reproduce during their first year, commencing at around six months of age. Females as small as 68g were observed with eggs (see image right). Preliminary field observations indicated that the majority of females BSC commence spawning at slightl la ge size ≈ 120g – 150g.

45) Field observations indicated that the weight of eggs carried by a female crab5 is highly dependent on the weight of the female crab. Very large SLBSC (i.e., > 250 g see image below right of a 460 g male crab on the same scale right) were noted to bear as much as 50 g of eggs. Females weighing 200 g to 250 g were considered to be normal sized adults local fishermen.

46) A note was made of an observation by one participant, who alleged that the SLBSC fishery off the eastern coast of Trincomalee District comprises mainly male SLBSC. No field evidence was gathered to corroborate this claim.

47) No evidence of specific nursery grounds for SLBSC was observed during the field survey. Jayamana notes that juvenile crabs are commonly associated with mangrove roots and sea grass beds (2011), which are found extensive in the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Bay.

48) Considerable stands of fringing mangrove are found in Dutch Bay (>250 ha) and Puttalam Lagoon (>750 ha), together with extensive sea grass beds. Fringing mangroves and sea grass beds are also present throughout the Sri Lanka side of the Palk Bay and in Jaffna Lagoon.

5

12

b. Physical Profile

49) The physical profile of the SLBSC fishery described in this report encompasses the geographic scope for the fishery and the fishing season. The physical profile also includes a description of the fishing craft and gear used by Sri Lankan fishermen6 to harvest SLBSC. Reference is also made to legal and illegal fishing gears use to harvest SLBSC, including mesh sizes. The history of the SLBSC fishery is also examined as recounted by older fishermen (oral history), as well as from the records of crab fish catch data collected by the Depa t e t of Fishe ies a d A uati ‘esou es DFAR) extension staff. The physical profile of the SLBSC fishery concludes with an examination of external issues that are perceived as having a negative impact on the SLBSC fishery and a brief description of fisheries other than the SLBSC that fishermen engage in.

50) Geographic Scope: The SLBSC fishery extends from

Negombo on the southwest coast, 40 km north of the capital Colombo, to an unidentified location off the coast of Trincomalee District (possibly Pulmoodai) on the northeast coast, a distance of approximately 600 km (see map right). The core area of the SLBSC fishery is located on the Sri Lankan side of the Palk Bay. A smaller fishery for BSC operates in Portugal Bay, while “LB“C a e also aught as pa t of a ulti spe ies lagoo fishe i Puttala Lagoo . The SLBSC fishery in all these locations operates in shallow seas of between 3 – 7 fathoms (18 ft – 42 ft / 6 m – 14 m). Fishing for SLBSC takes place in coastal waters up to a distance of 2 km to 10 km from the shoreline and in two large lagoo s - Puttalam Lagoon in Puttalam District and Jaffna Lagoon in Jaffna district.

51) Puttalam Lagoon, which comprises Puttalam Lagoon and Portugal Bay and covers an area of 32,680 hais technical not a lagoon, but a bar built estuary. Jaffna Lagoon is low lying area of land submerged by a combination of the diurnal rise and fall of the sea (average tidal amplitude is around 0.7 m) and seasonal run off of rainwater from the surrounding land during the northeast monsoon. Puttalam Lagoon and Jaffna Lagoon undergo marked changes in salinity during the course of the year, from brackish to hypersaline.

52) SLBSC are most common within the geographic range of the fishery over soft substrates i.e., and or mud. SLBSC are less commonly found over hard substrates such as coral and sandstone reefs as found off the coast of Puttalam District and the north coast of the Jaffna Peninsula. Three spot swimming crabs (P. sanguinolentus), for which there is little commercial demand, are more common over coral and sandstone reefs. SLBSC caught in Jaffna Lagoon mainly form part of the bycatch of the prawn stake net fishery (see external issues below) and the bottom-set baited trap fishery. The small size of the SLBSC caught in these fisheries (<80g) ensures that they do not enter the main – export orientated - supply chain for SLBSC (see supply chain below). As such, BSC caught in stake nets and baited traps are considered part of the SLBSC fishery, for the purpose of the assessment.

53) Each fishing village along the northwest and northern coast has its o fishi g a ea . The a ge of ea h lo al fishi g a ea is likely to be determined primarily by fuel cost incurred in reaching and returning f o the fishi g g ou ds fo e ha ised fishi g aft , as ell as the ou da ies of lo al fishi g gou ds lai ed eigh ou i g illages o illages i adja e t dist i ts. Lo al fishi g a eas a e located 2 km to 10 km from an individual fishi g o u it s la di g e t e. It as e ide t that these lo al fishi g a eas , although i fo al e e recognised and adhered to by SLBSC fishing communities. The traditional right to SLBSC from the fishery is thus shared among fishing communities, by means of smaller lo al fishi g a eas in the Palk Bay, Portugal Bay and Puttalam Lagoon.

6

Almost without exception individuals catching SLBSC are men, hence the use of the term fishermen throughout. Woman may occasionally be boat owners, for example when husband has died during the conflict.

Core Area

Negombo

Pulmoodai

13 54) Fishing Season: SLBSC are present in the fishing area throughout the year in all four of the districts. The duration of the fishi g seaso fo SLBSC in any one area depends on the location of the individual fishing community, the weather, the type of fishing gear used and economic returns from alternative fisheries (see Alternative Fisheries below). The main fishing season for SLBSC starts as early as August in Portugal Bay, the sheltered, northern tip of Puttalam Lagoon. In Jaffna District the fishing season starts in September each year, while in Mannar and Kilinochchi districts October is the month when fishermen focus their fishing effort on harvesting SLBSC. The peak fishing season occurs over a period of three to four months in each location. March to June in Kalpitiya; January to April in Jaffna and November to Fe ua i Ma a . The fishi g seaso e ds i Ap il, Ma or June, depending on the location. July, August and September forms the core of the offseaso fo the SLBSC fishery in all four districts.

55) The BSC fishing season is closely aligned with the strongly season weather patterns along the northwest and coast of Sri Lanka. There are two main monsoons - the northeast monsoon (NEM) and the southwest monsoon (SWM) – as well as two distinct two inter monsoon seasons associated with convectional and depressional weather systems. The SLBSC fishery commences with the onset of the second to the two inter monsoonal rains in October, which are caused by cyclonic depressional meteorological processes in the Bay of Bengal. The SLBSC fishery continues throughout the NEM, which begins in December and continues through to February every year. The peak fishing season is associated with the end of the NEM and the commencement of the second inter monsoonal rains, which begin in March each. The second inter monsoonal rains are the result of convectional meteorological processes. The offseason is associated with the SWM rains in June, July and August. The SWM begins in the southwest of the country and gradually travels up the western coast, but does not reach the core area of the SLBSC fishery, off the north western coast.

56) The offseaso is likely to be a consequence of the calm weather systems off the northwest coast and the fishe e s use of lo et to ha est SLBSC. As the turbidity of the water gradually declines after the end of the second inter-monsoons, nylon nets becomes increasingly more visible to the SLBSC. As a result the crabs are better able to avoid becoming entangled in the nets. The converse is true for the start of the fishing season, as the turbidity of the sea increases with the onset of the second inter-monsoon in October each year. Strong winds during the NEM hinder but to not prevent fishing activities in December through to February. The relatively weaker weather systems associated with the second inter monsoon enable fishermen to fish more frequently. The increased turbidity prevents SLBSC from avoiding the fishe e s nylon nets. One of several advantages of fishing with illegal monofilament gill nets is that these nets are invisible to SLBSC when water turbidity is low. This greatly increases the efficiency of illegal monofilament gears (see below).

57) Fishing Craft: The SLBSC is conducted from traditional Sri Lankan outrigger canoes (oruwa), log rafts (theppam7), canoes (vallams) and fibre reinforced plastic (FRP) boats (17½ and 23ft). The larger vallams and all of the FRP fishing craft (see right) are powered by small, kerosene fuelled, outboard motors (8.8 hp and 9 hp).

58) Data describing the total number of fishing craft registered in the four districts was used to estimate the total number of fishing craft engaged in the SLBSC fishery (see Table 3). The analysis suggests as many as 7,000 fishing craft may be involved in the SLBSC fishery. As much as 80% to 90% of fishermen in SLBSC fishing villages engage in the fishery during the peak fishing season. An analysis of landing site specific boat registration details and fishing licences issued for crab fishing by the respective district level offices of the DFAR, was not possible during the course of the assessment.

7

14

Table 3: The type and estimated number of fishing craft engaged in the SLBSC Fishery, by district

Type of Fishing Craft Non Mechanised

Traditional Craft

Mechanised

Traditional Craft FRP Craft

Estimated No. of SLBSC Fishing Craft

Puttalam District 1,380 216 432 2,028

Mannar District 410 195 ,687 2,292

Kilinochchi District 162 117 324 603

Jaffna District 810 410 858 2078

2,762 938 3,301 7,001

59) Fishing Gear: Bottom-set gill nets (crab nets), made of nylon twine or monofilament plastic, are the main fishing gear used by fishermen to catch SLBSC (see right). Since 2006 the use of monofilament nets has been illegal in Sri Lanka8. The mesh size of both nylon and monofilament crab nets ranges f o ½ to . The smaller mesh sizes are used in lagoons and shallow area by fishermen fishing from non mechanised traditional craft. The larger mesh sizes are used in deeper coastal waters by the mechanised FRP fishing craft. The commonest mesh sizes are ½, ½ a d . The thickness of nylon nets ranges from 1ply to 21ply twine. Three ply is commonly used during the NEM, while 6ply and higher is used after the monsoon due to the increase in debris in the water.

60) A single nylon crab net set comprises between 10 and 25 pieces (rolls) of nylon net. Depending on the size of the fishing craft a fishermen may set two to five crab nets per fishing trip, equal to around 50 net pieces. Crab nets are set on the seabed, by the use of weighted poles (see below right) in the early evening. Crab nets are hauled by fishermen after eight to ten hours. Many fishermen now use geographic positioning systems (GPS) to record the location of their crab nets. The use of GPS enables fishermen to dispense with the need to use surface buoys to identify the location of their nets.

61) There appears to be a strong positive correlation between mesh size – both nylon and monofilament crab nets - and the minimum size of crabs that are caught in the nets. As mesh sizes increase, the minimum size of the SLBSC caught in the crab nets decreases (see Table 4).

62) A small number of fishermen harvest SLBSC using baited t aps. T o a ieties of aited t aps: otto set o t aps a d suspe ded lift et t aps a e used. A e t pe of fishing net, known locally as neela valai (blue net), has recently come into use in Jaffna District.

8

15

Table 4 Summary of the relationship between mesh size, crab size and markets

Size of SLBSC Caught Market Other Species Caught

Mesh Size

½ SLBSC is bycatch Local Target Lagoon Finfish

½ Small crabs 100g – 150g. <200g Local & Export Finfish Small crabs 100g – 150g. <200g Local & Export Bycatch

½ Broad range 100g Not many 120g - 150g – 500g; Export Market Bycatch 300 g – 400 g Export Market Bycatch 300 g – 400 g Export Market Bycatch

63) Illegal Fishing Gear: Although monofilament nets are prohibited under the Fisheries & Aquatic Resources Act in Sri Lanka, monofilament crab nets are used to harvest SLBSC, most notably in Puttalam Lagoon and in Jaffna District (see right). In Jaffna District is possible that as much as 75% of the catch is landed using monofilament nets. Monofilament nets are preferred by fishermen because of their higher catching efficiency, which in turn is a result of the invisibility of monofilament nets in the water. As noted above, SLBSC are unable to avoid the nets, even when the visibility is good (i.e., when turbidity is low) in contrast to nylon nets which are more visible.

64) Monofilaments nets are a little less durable than nylon nets – two to three months compared to three to four months for nylon nets – and have to be replaced more often. However, monofilament nets are less expensive than nylon nets. According to fishermen less bycatch is caught using monofilament nets compared to fishing with nylon nets and monofilament nets are also easier to clean. The higher incidence of monofilament crab nets in Jaffna District can be partly explained by the fishing restrictions that were in place during most of the recently concluded conflict. For long periods during the past 30 years, Jaffna fishermen were only permitted to fish between 6 am and 6 pm each day. The use of monofilament nets during this period was the only means by which fishermen were able to harvest fish during the daytime.

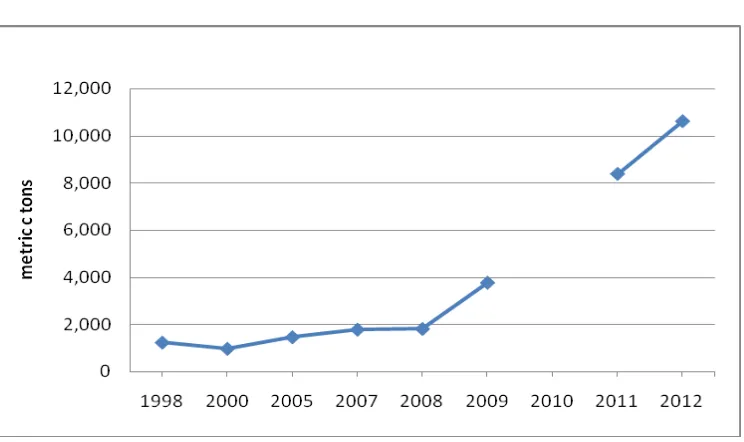

16 66) SLBSC Production: The p odu tio data olle ted the DFA‘ s e te sio offi e s from the SLBSC fishery does not discriminate between commercial crab species. Thus the annual crab production data presented in Figure 2 below, includes not only SLBSC, but also the landings of other commercial crab species in Sri Lanka, principally the mangrove crab (Scylla serrata) and the three spot swimming crab (P. sanguinolentus). Despite these limitations, it is clear from DFA‘ s data that the production of crabs in Sri Lanka - including SLBSC - has increased considerably since 2008. The increase in crab production coincides with the end of the civil conflict in Sri Lanka and the resurgence of the fishery sector in the coastal districts that comprise the Northern Province (i.e., Mannar, Kilinochchi, Jaffna and Mullaitivu). As SLBSC is the main crab species caught by fishermen in the Northern Province, there are reasonable grounds to infer that the overall increase in national crab production is a consequence of increasing catches of SLBSC.

Figure 2 Annual Sri Lankan crab production for all crab varieties

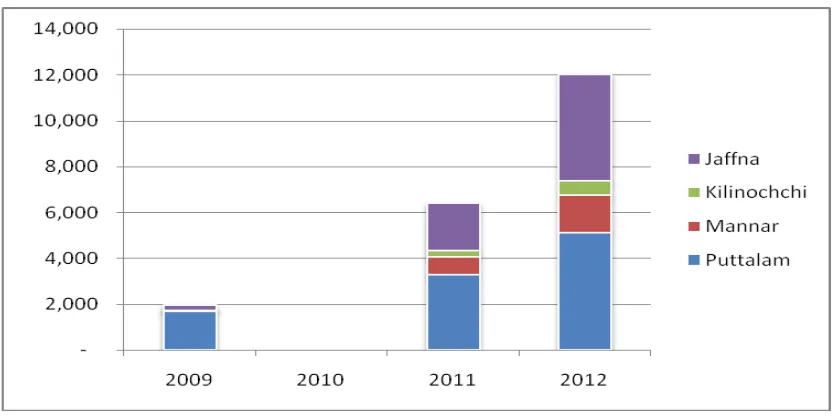

67) Production data from the four coastal districts that constitute the core geographical area of the SLBSC fishery (i.e., Puttalam, Mannar, Kilinochchi and Jaffna), further underlines the growth of the SLBSC in the northern districts (see Figure 3). Here too it should be noted that this data i ludes all varieties of crab . The data collected by DFAR extension staff indicates that crab production has increased in all four districts, with the largest increase taking place in Jaffna District. In 2009 crab production in Jaffna District was 240t. In 2012 crab production increased to 4,630t: an increase of 1,829%. The corresponding increases for Kilinochchi, Mannar and Puttalam were 146%9, 162,000% and 198% respectively.

68) The accuracy of the o thl statisti al epo ts o piled the DFA‘ s e te sio staff, in the north and nationwide, is a concern. Despite these concerns, the production data is at least indicative of a considerable increase in crab production in off the northwest coast following the end of the civil conflict in 2009.

9

17

Figure 3 Comparative increases in crab production in four districts since 2009

69) Corroboration of the substantial increase in crab production can be found in the data compiled independently by the Customs Department for export crab products (see Figure 4). According to export destination data compiled by the Customs Department the crab fishery in Sri Lanka has increased by 165% in the three years following the end of the civil conflict. The value of crabs exported from Sri Lanka increased from around LKR 1,000 million (US$ 7.75 million) in 2009 to LKR 1,560 million (US$ 12.09 million) in 2011. The increase in value of crabs exported from Sri Lankan (56%) is widely attributed to the increased catch and export of SLBSC10.

Figure 4 Export destinations and value (LKRs) of crab exports 1990 to 2011

70) Oral testimonies of senior representatives of the fishing communities further substantiate the crab fishery production data collected by the DFAR. In Kalpitiya (Puttalam District), the number of seafood companies purchasing SLBSC was observed to have increased considerably over the past 25 years. Earlier only one collecting centre was present in Kalpitiya and only one or two seafood companies were directly buying SLBSC. Now there are more than eight collecting centres and a dozen or more seafood companies are directly involved purchasing SLBSC.

10

18 71) Over the last ten years the number of fishermen and fishing effort was perceived to have increased in Puttalam District. Although the total production is perceived to have increased, fishing communities expressed concern that the catch per boat has declined. There is also a perception of a downward shift in the size of SLBSC caught. According to local fishermen and traders, ten years ago most SLBSC caught were large crab (>200g). Now the majority of SLBSC caught are medium crabs (150 g – 199g).

72) Changes in the SLBSC fishery in Mannar District have happened more recently. Only five years ago fishermen regularly used a stick to break the legs and claws of SLBSC entangled in their nets. At the time there was no dedicated fishery for SLBSC, which were part of the bycatch from various coastal finfish fisheries. As recently as 2008 there was no commercial demand for SLBSC. SLBSC were and are still ie ed as poo peoples food . “LB“C a e eaten locally, with only weak demand from regional or national markets. SLBSC are not a popular seafood product in Sri Lanka.

73) The national market for SLBSC is limited to hotels, targeting foreigners and middle class Sri Lankans. In Mannar District fishermen have switched to SLBSC fishing due to strong export demand for SLBSC from seafood companies. Before the arrival of the seafood companies, a kilo of very large SLBSC (>400g) was LKR200.00 kg1 (US$1.52). Now the wholesale prices is above LKR500.00 kg1 (US$3.81) for large SLBSC (>200g). Very large SLBSC (>400g) are still regularly caught in by fishermen in Mannar District, although there is no premium price for very large crabs.

74) The rapid increase and continuing strong demand from seafood companies is a key factor driving the expansion of the SLBSC fishery in Kilinochchi District and in Jaffna District. Elder fishermen in both districts related how as little as four years ago they would curse the sight of shoals of SLBSC. Nets would be hauled and reset elsewhere and crabs would be beaten from the nets at sea because there was no market for SLBSC in either district. As was the case in Mannar District, there was no dedicated fishery for SLBSC in either district prior to the end of the conflict (2009). In contrast to less than five years ago, now when fishermen sight a shoal of SLBSC they are pleased. When the net are hauled fishermen are careful when removing the crabs and are mindful to keep them alive.

75) The purchasing price offered by seafood companies is the driving factor behind the change in fishe e s attitude a d eha iou to a ds SLBSC. Before the arrival of the seafood companies the local wholesale prices for a kilo of large SLBSC was LKR30.00 (US$0.23) in Jaffna and LKR5.00 (US$0.04) per crab in Kilinochchi. The same crabs are now sold for LKR500 to LKR600 kg1 (US$3.81 – US$4.57).

76) Elder fishermen did not report any changes in the size of SLBSC that are currently being caught in Jaffna District. Very large crabs (>400g) are still regularly harvested from the fishery. In Kilinochchi District some concerns were raised regarding the prospect of declining catches, now and in the future, if action is not taken to improve certain aspects of the fishery such as harvesting small crabs (<100g) and female crabs with eggs.

77) Externalities: The lagoon and near shore stake net fishery for prawns (Puthi Velai / Kattu Del); illegal trawling by Indian and Sri Lankan trawlers and irregular migration by fishermen from coastal communities are the key external issues affecting the SLBSC fishery, in the four districts covered by the assessment.

78) Stake Net Fishing: The prawn stake net fishery is the dominant fishery in Jaffna Lagoon and is common

19

79) Indian Trawlers: The maritime agreement signed

between GOSL and the Government of India (GOI) in 1974, demarcates the International Maritime Boundary Line (IMBL) between the two countries in the Palk Bay (see right). The agreement states that each country shall have sovereignty and exclusive jurisdiction and control over the waters, the islands, the continental shelf and sub soil thereof, falling on its own side of the aforesaid boundary (Article 4). Acknowledging the historic use of the Palk Bay and Islands, notably Kachchativu, by fishermen from south India and northern Sri Lanka, the agreement ensures that Indian fishermen and pilgrims will enjoy access to visit Kachchativu as hitherto, and will not be required by Sri Lanka to obtain travel documents or visas for these purposes (Article 5). The agreement goes on to stipulate that the vessels of India and Sri Lanka will enjoy in each other s waters such rights as they have traditionally enjoyed therein (Article 6).

80) Illegal fishing by Indian fishermen, in the Sri Lankan half of the Palk Bay has been an issue between the two countries since the Palk Bay were officially partitioned in 1974. South Indian trawlers owners, of which there are more than 2,000 harboured in Nagapatinam, Kodikarai, Thondi, Rameshwaram and Pampan, continue to claim that they have a right to fish on the Sri Lankan side of the IMBL. Throughout the civil conflict, control of the Sri Lankan side of the Palk Bay was highly contested by the go e e t s security forces and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Indian trawlers took advantage of the inability of the GOSL to effective patrol the area and the restrictions placed on Sri Lankan fishermen during the civil conflict. Sri Lankan fishermen were confined to fishing between 6 am and 6 pm.

81) An agreement reached between small scale Indian fishermen and Indian trawler owners, currently restricts Indian trawlers to operating for only three nights per week on both sides of the IMBL: Monday, Wednesday and Saturday. When they cross over into Sri Lankan waters, the much larger Indian trawlers, towing heavy bottom trawls, dest o o the “ i La ka fishe e s u h lighter fishing gears. The Indian trawlers also represent a very real threat to the safety Sri Lankan fishing boats.

82) Following the end of the conflict, northern Sri Lankan fishermen have become more vocal in disputing the legal right of Indian trawlers to fish on the Sri Lanka side of the Palk Bay. Recently a number of articles have appeared in the Sri Lankan press, advocating for the right of northern Sri Lankan to fish freely in Sri Lankan waters of the Palk Bay The GOSL has also stepped up direct action against Indian trawlers caught fishing in Sri Lankan waters in the Palk Bay. Since 2009, hundreds of Indian fishermen have been arrested and their boats impounded by the GOSL.

20 84) Sri Lankan Trawlers: Bottom trawling in Sri Lanka is prohibited by the MFAR, in accordance with paragraphs 31 and Paragraph 32 of the Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act of 1997. The Act entitles the Minister to ban or limit any fishing activity that is deemed to be detrimental to the marine ecosystem or the livelihoods of fishing communities, on the advice of the Advisory Committee to the Minister11.

85) Ttrawling for resource that are then exported is also prohibited under Regulation No. 4. of the Fishing (Import & Export Regulations (2010 1665/16). The Act states that no person shall engage in any dredging at the sea bed or undertake trawling operations within Sri Lankan Waters in relation to any activities specified in this regulation for which a fishing operating licence has been issued .

86) In accordance with the directive of the Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources and the regulation cited above, the DFAR does not issue boat or fishing licences for bottom trawling in Sri Lanka. The operation of Sri Lankan trawlers and the use of bottom trawls is thus illegal.

87) Despite the ban on trawling, around 300 or so trawlers (see right) continue to operate from harbours and anchorages in Kalpitiya (Puttalam District), Pesalai (Mannar) and Kurunagar (Jaffna District). Political patronage is believed to be the reason for the trawlers continued ability to operate. The Kalpitiya trawlers fish mainly for prawns, but also harvest cuttlefish and SLBSC from Portugal Bay. Jaffna trawlers also target prawns, cuttlefish, SLBSC and squid. Jaffna trawlers fish off the coast of Mannar and Kilinochchi, as well as the Jaffna coastline.

88) Although smaller than their Indian counterparts, Sri Lanka trawlers cause damage to the marine ecosystem: through the action of bottom trawling and as a result of the bycatch landed or discarded by the trawlers. Sri Lankan trawlers are also implicated in the damage and destruction of crab nets and are a threat to the safety of smaller Sri Lankan fishing craft. Sri Lankan trawlers operate on the same nights as the Indian trawlers, taking advantage of their larger counterpart s greater threat to the lives and livelihoods of small scale fishermen.

89) Migration: Migration by fishermen and women from coastal communities along the northwest coast, is

also an external factor affected the SLBSC fishery. Regular and irregular migration from the north, by people seeking political asylum, has been a persistent feature throughout the 30 year long civil conflict in Sri Lanka. There are now large expatriate Sri Lankan communities, both Sinhalese and Tamil, in Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, Norway and Switzerland. Since the end of the conflict there has been a rise in irregular migration to Australia, on aboard Sri Lankan multiday fishing boats. In 2011 over 5,000 people were arrested by Sri Lankan Navy, onboard multiday boats heading for Australia. More 1,300 Sri Lankans, Sinhalese and Tamils, had reached Australia and claimed asylum, as of July 2013.

90) 40 fishermen from Jaffna had been arrested off the southern coast of Galle, in the week prior to the field survey in Jaffna District. Representatives of fishing communities and reports in the press suggest that the motivation for undertaking irregular migration is primarily economic, regardless of the risks involved. Despite the economic recovery associated with the end of the civil conflict, fishing communities are well positioned to engage with agents in the fishery sector, who continue to promote irregular migration as viable way out of social and financial hardships faced by fishing households in the north west of Sri Lanka.

11

21 91) Alternative Fisheries: Fishermen in all four districts are not solely dependent on the SLBSC fishery for their livelihoods. Other economically important fisheries include jacks and trevallies (carangids), Indian Mackerel (scombroids), prawns and cuttlefish, needlefish (Belondae), silverbiddies (Gerres spp.,) rabbitfish (Signathus spp.,) emperor fish (Letherinds), mullet, sardinellas and trenched sardines. SLBSC fishermen switch gears and fisheries throughout the year, depending on the availability and wholesale value of different fisheries.

c. Social Profile

92) The social profile of the SLBSC fishery includes an overview of the fishing communities engaged in the exploitation of the SLBCs and the organisation of fishermen and women at the village, divisional, district and national level. The social profile also examines the role of women in the SLBSC fishery and draws attention to the key issue of indebtedness faced by fishing communities and the role played by investment made by traders and seafood companies in individual SLBSC fishery operations.

93) Fishing Communities: Sinhalese, Tamil and Muslim fishing communities are engaged in the exploitation

of SLBSC off the northwest coast of Sri Lanka. Fishermen representing all three communities are present in Kalpitiya and Wannathawiluwa (Puttalam District). Tamil and Muslim communities are found in Mannar and Kilinochchi districts. In Jaffna District the fishing community is exclusively of Tamil origin, as a esult of the LTTE s fo ed e pulsio of al ost , Musli s f o Jaffna District on 15th October 1993. Following the end of the conflict, Muslim households have begun to return to their villages on peninsular.

94) An analysis of the consolidated data provided by the Statistical Unit of the MFAR suggests that as many as 20,000 fishing household may be dependent on the SLBSC fishery in the four the districts. Detailed district and divisional data are available with the DFAR offices at the district level and with the MFAR in Colombo. The Consultant was unable to obtain and analyse these data due to administrative procedures and the timeframe of the assessment.

95) Organisation: There are two parallel

organisational structures representing the interests of fishermen and women in Sri Lanka: Fishe e s Coope ati e “o ieties FC“ a d ‘u al Fisheries Organisations (RFO). FCS fall under the administrative jurisdiction of the Department of Cooperative Development (DCD). The DFARs support and input to FCS is restricted to technical assistance and registration related to fishing and includes social welfare.

96) The subject of cooperative development falls under the Concurrent List of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution and thus is shared subject between the central government and provincial ad i ist atio s DCD. FCSs represent fishermen and women at the village level. In Mannar, Kilinochchi and Jaffna districts, divisional level federations of FCS represent the interests of fishermen and women at the divisional administrative level.