ATOMIC THINKING WITH BENJAMIN AND BATAILLE ON THE VIOLENCE OF REPRESENTATIONAL ENCLOSURES

by Julie Hawks

A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in

Religious Studies Charlotte

2013

Approved by:

______________________________ Dr. Joanne Robinson

______________________________ Dr. Kent Brintnall

©2013 Julie Hawks

ABSTRACT

JULIE HAWKS. A cloud of unknowing: Atomic thinking with Benjamin and Bataille on the violence of representational enclosures. (Under the direction of

DR. JOANNE ROBINSON)

What are the ethical implications of what and how we, as Americans, remember the bombing of Hiroshima? Historical narratives strive for closure in an attempt to control how we understand the past, present, and future. Ethics and morality, by definition, rely on closed systems of meaning that dictate right and wrong. The very existence of the system propagates violence. Walter Benjamin’s and Georges Bataille’s

projects prompt us to consider a new ethics unhinged from society’s mandated norms— an ethics that springs from the instant or the “now” of the individual’s experience. Their writings convey a conviction that our current system of morality cannot lead us into a nonviolent future. In this thesis, I use Hiroshima as a case study to explore both the writings of Benjamin and Bataille, and to explore as well Alain Resnais’ two films Night and Fog (Nuit et Brouillard) and Hiroshima mon amour. In doing so, I examine what an

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This thesis would not have been possible without the guidance and encouragement I received from Drs. Joseph Winters, Kent Brintnall, and Joanne Robinson. Their dedication to quality and their exemplary teaching methods greatly influenced my academic study. They could not have better prepared me for the work of this thesis or my future academic endeavors. I would like to thank Dr. Winters for introducing me to the writings of Walter Benjamin and Toni Morrison, which have shaped my thinking around historical and trauma narratives. I need to thank Dr. Brintnall for his contagious love for Georges Bataille and the transgressive, both of which have forever altered how I view the world. Most importantly, I must thank Dr. Robinson, who is my mentor for teaching and research, and my friend.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the Religious Studies Department for showing their confidence in me by providing financial support through a Graduate Teaching Assistantship.

INTRODUCTION

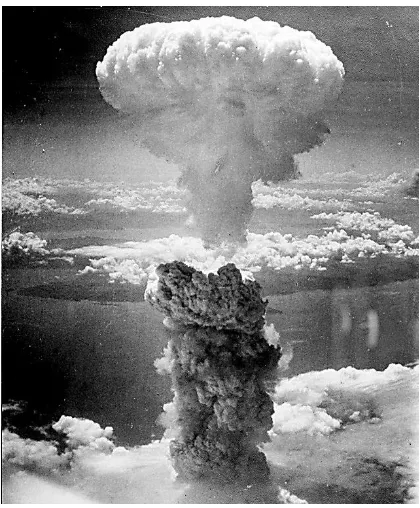

FIGURE 1: Mushroom cloud, somewhere over Japan, 19451

The mushroom cloud stands as the icon for Hiroshima as the first nuclear

destruction of a human society.2 Hiroshima and Nagasaki are conflated into this singular representation, the only identifiable image of these cities’ decimation for most

Americans. Absolute U.S. censorship in Japan suppressed photographic evidence of human suffering for a decade following the bombing (and much longer for classified materials). Press censorship in post-war Japan applied to all aspects of cultural

1 August 9, 1945, the bombing of Nagasaki.

2 It should be noted here that the image of the mushroom cloud is

production, including films, children’s books, and music.3 To complicate matters further, these strict censorship measures concerning the bombing and its human effects curtailed public discussion, especially among the residents of Hiroshima. Additional propaganda added to these silencing measures determined how survivors’ stories were then told and, in turn, cast how the world would come to understand Hiroshima and the United States.4 An American documentary film crew recorded color images, which were then ordered by the United States military to be locked away for forty years. 5 Testimonies of atrocity were silenced by death, trauma, and censorship. That cloud of unknowing continues today.

The title of this thesis is a nod to The Cloud of Unknowing, a fourteenth century

spiritual guide on contemplative prayer. The underlying message of that work suggests that the only way to truly “know” God is to abandon all preconceived notions and beliefs (knowledge) about God, and to have the courage to surrender one’s self to “unknowing,” so that the true nature of God will become visible. So it is with the “history” of

Hiroshima.6 Real knowledge is built on completeness, but history is in motion as long as

3 Occupation censorship forbade criticism of the United States as well as other Allied nations. Even the

mention of censorship itself was forbidden. Robert Karl Manoff, "The Media: nuclear secrecy vs.

democracy," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 40, no. 1 (1984): 28. All publishable materials fell under strict

censorship, including films, children’s books, and musical recordings. Tanka poet Shione Shoda was threatened with the death penalty if she published her collection of poems. Kyo Maclear, Beclouded Visions: Hiroshima-Nagasaki and the Art of Witness (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1999), 42. This meant that “Occupation censorship was even more exasperating than Japanese military

censorship had been because it insisted that all traces of censorship be concealed.” David M. Rosenfeld,

Dawn to the West (New York: Henry Holt, 1984), 967, quoting from Donald Keene in Unhappy Soldier: Hino Ashihei and Japanese World War II Literature, 86.

4 Propaganda and censorship play a role even today in how the atomic bombing is allowed to be

represented, as will be seen in the discussion about the failed Enola Gay exhibit in Washington, D.C.

5 Greg Mitchell, "For 64th Anniversary: The Great Hiroshima Cover-Up -- And the Nuclear Fallout for All

of Us Today," Huffington Post, August 6 2009, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/greg-mitchell/for-64th-anniversary-the_b_252752.html (accessed March 9, 2013).

people are alive to add to it. Therefore, what historical knowledge do we actually have, and what are we to do with that knowledge?

Suppose in a conversation about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima someone says: “The only ethical response to this traumatic episode is to try to understand what happened as clearly and comprehensively as possible. We need to make sense of this event!” How do (and should) we, as Americans, understand and remember the bombing of Hiroshima? What are the ethical implications of what and how we remember—the memory and trauma of—this event? This thesis is my response to these questions.

Susan Sontag, in her book Regarding the Pain of Others, sums up the frame of

reference from which my thesis is positioned:

Which atrocities from the incurable past do we think we are obliged to revisit? . . . Probably, if we are Americans, we think that it would be morbid to go out of our way to look at pictures of burnt victims of atomic bombing or the napalmed flesh of the civilian victims of the American war on Vietnam. . . The acknowledgment of the American use of disproportionate firepower in war (in violation of one of the cardinal laws of war) is very much not a national project. A museum devoted to the history of America’s wars . . . that fairly presented the arguments for and against using the atomic bomb in 1945 on the Japanese cities, with photographic evidence that showed what those weapons did, would be regarded—now more than ever—as a most unpatriotic enterprise.7

Sontag questions our personal and societal responsibility to view photographic evidence of atrocity. The individual, however, may choose to turn away from any image that makes him or her feel bad: “In a modern life—a life in which there is a superfluity of things to which we are invited to pay attention—it seems normal to turn away from images that simply make us feel bad.”8 It is not a national priority to educate American

7 Susan Sontag,

Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 93-94.

8 Ibid., 116.; William James claims that it is perfectly natural for people to want to remain within the

citizens about the questionable and unlawful tactics that the U.S. military repeatedly executes against our foreign neighbors. On the contrary, high-ranking members of our government and military actively engage with media establishments to misinform the public through patriotic rhetoric and consumerist advertising. Propaganda and misdirection are understandable, albeit unscrupulous, strategies incorporated by institutions fearing their own waning power. In other words, in the interest of

maintaining a positive and cohesive identity in the world, it is not conducive for a country to allow or even encourage contradictory information or questioning. This reality

presents the individual with the unenviable choice to conform and remain safely within the confines of the Nation, or to question the available information and put everything at risk. The individual willing to take that risk and ask for more (or conflicting) information than what society willingly offers is then faced with the dilemma of confronting

unpleasant realizations and guilt, which jeopardize personal and national identity with the peril of also being labeled unpatriotic.9

In order to discuss ethical responses to remembering and understanding the bombing of Hiroshima, I include concrete examples of how Americans have remembered this event ever since President Truman’s radio address on August 6, 1945. There is no single remembrance, although official military statements have varied little over the

The systematic cultivation of healthy-mindedness as a religious attitude is therefore consonant with important currents in human nature, and is anything but absurd. In fact, we all do cultivate it more or less, even when our professed theology should in consistency forbid it. We divert our attention from disease and death as much as we can; and the slaughterhouses and indecencies without end on which our life is founded are huddled out of sight and never mentioned, so that the world we recognize officially in literature and in society is a poetic fiction far handsomer and cleaner and better than the world that really is.

William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (Megalondon Entertainment, 2008), 77.

years: We gave Japan every opportunity to surrender and they refused. . . The bomb had to be dropped in order to bring a speedy end to the war, saving hundreds of thousands of lives. . . Dropping the atomic bomb allowed the Japanese to “save face” in their

inevitable surrender. . . Japan would not have surrendered so quickly if Hiroshima and Nagasaki had not been bombed with atomic weapons.10

The media has played a central role in disseminating official U.S. government narratives about the event, as well as manipulating contesting viewpoints. Film (both documentaries and fictional accounts), literature, photographs, museum exhibits and public demonstrations against the exhibits, and news stories in popular magazines and newspapers have helped to mold public opinion. In order to maintain focus in this thesis, I will address only a thimbleful of these responses. I will present a number of “facts” related to the bombing. The reader will see, however, that even uncontested facts are challenged by how those facts are remembered. The principal information that will be explored in this thesis include Truman’s announcement of the bombing; repeatedly published photographs of the bombing and its effects; John Hersey’s August 1946 article published in TheNew Yorker, “Hiroshima;” and Alain Resnais’ two films Night and Fog

(Nuit et Brouillard) and Hiroshima mon amour. The writings of Walter Benjamin and

Georges Bataille provide the primary theories I use to analyze the events of, as well as

10 Modern scholarship has successfully challenged these narratives, but it is beyond the scope of this paper

to discuss the details of the refutations. However, I will state that the official findings of the U.S. Strategic Bomb Survey Report that was published less than a year following the attack stated that Japan would have surrendered even without the bomb:

Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts and supported by the testimony of the surviving

Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey’s opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and

in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated.

United States Strategic Bombing Survey: Summary Report (Pacific War), July 1, 1946.

the responses to, the atomic bombing. Other prominent voices included in this thesis are those of Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, Alain Resnais, and Marguerite Duras, all of whose writings contest common notions of seeing and remembrance.

I chose the writings of Benjamin and Bataille as the theoretical framework for this thesis for two important reasons.11 First, both writers offer insights that stem from

mystical approaches. The form of mysticism they illustrate in their writings ties into arguments I put forward in this thesis and echoes similar language found in trauma literature. This connection is important because the political arguments both writers explicate within the bounds of mystical understanding appear to align with the narratives of memory and trauma I am addressing in this thesis. This mysticism/negative

theology/apophaticism framework also connects straightforwardly with what I find powerful and generative in Resnais’ films and how all three (Bataille, Benjamin, and Resnais) appear to approach the memory of certain events. Second, Benjamin and Bataille both focus much of their efforts on critiquing society’s inclination towards fascism, suggesting ways to counter that inclination and its effects. I incorporate their writings as a perspective to examine popular media artifacts and narratives that

Americans use to remember Hiroshima and to examine the films and literature that challenge what and how we remember.

This thesis does not offer a comprehensive analysis of all available literature on the subject, nor does it focus on the Japanese or international response to the atomic bombings. My intention with this thesis is to explore how Americans, as the perpetrators

11 Allan Stoekl, in a footnote to his introduction to

of the atrocities suffered by the residents of Hiroshima, have understood and remembered the bombing and its subsequent effects. I limit my focus to American narratives for several reasons. First, I wanted to show that reducing the remembrance of Hiroshima to the narratives of a single society still presents a very complex recollection. Even within the constraints of “the American narrative” we can see that there is no single story. Second, as I was researching information for this thesis, I noticed a recurring “call for peace” in response to the bombings that appeared across most of the literature that I had read. I was fascinated that the city of Hiroshima, the site of the world’s first nuclear attack, would come to be known as the “City of Peace.” Even Japan’s memorial museum dedicated to the atrocity is named the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. I wanted to see if I could trace this perspective back to American narratives. And finally, Bataille’s writings inspire a desire in me to consider the American remembrance of Hiroshima from a “guilty” perspective.12

I found it necessary to include a few specific responses to the Holocaust that have impacted how we currently remember Hiroshima. Just as the nuclear annihilation of Nagasaki conflates into two singular representations—the image of a mushroom cloud and the name “Hiroshima”—the Holocaust conflates into the image of a gas chamber and the name “Auschwitz.” Throughout this thesis, I refer to these metonyms, “Hiroshima” and “Auschwitz,” as signs pointing to much larger and complicated histories. Again, my responses are not all-inclusive, but are incorporated in order to reveal the complex and

12

Inner Experience and Guilty and several essays compiled within Visions of Excessaddress Bataille’s contemplations before and during World War II. These writings act to disrupt the reader’s notions of self and knowing and are useful for reassessing narratives of “justified” aggression, such as those propagated in

dynamic nature of collective remembrances of these traumatic events, especially those contesting shared culpability.

Hiroshima and Auschwitz are inextricably intertwined on many levels above and beyond being time-bound within World War II. Over the course of the war, the involved nations’ militaries exhibited an ever-increasing propensity to target civilian populations for their own political gains. Americans, for the most part, seem more capable of discussing Auschwitz because we do not view ourselves as the perpetrators; rather we view ourselves as the liberators. This view can be located within our master narratives. We can look at films and objects housed within museums that deal with Auschwitz from a purportedly less biased (or rather, guilty) position.13 By exploring our relationship with these narratives, we are offered tools that enable us to better decipher how we understand Hiroshima. One specific example to consider is Alain Resnais’ poignant documentary,

Night and Fog (Nuit et Brouillard) (1955), which focuses on the ethics of memory related

to the Nazi death camps, because it greatly influenced future narratives integrated by Holocaust museums and films, as well as his own succeeding film Hiroshima mon amour.14

I wanted to include a chapter that addressed American responses to the Vietnam War in relation to how we think about Hiroshima in order to show how changing political climates contribute to radical changes in the positioning of official historical narratives.

13 Using metaphor from Georges Bataille’s writing, we are blinded if we try to look directly at the sun. In

this vein, to directly look at all Hiroshima represents, our guilt would be too overwhelming. Instead, we must look indirectly in order to begin to comprehend what Hiroshima means. I interpret this meaning from Georges Bataille, "Rotten Sun," in Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939, trans. Allan Stoekl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1985), 57-58.

14 Another connection between these films and the theme of this thesis lies in the imagery of clouds

Although Vietnam may seem quite removed from the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, these separate American invasions are irrevocably entangled. Over and above the obvious racial bigotries that contributed to the unrepentant acts of aggression and violence overseas and at home on American soil, it was not until the 1970s, when

America’s military suffered world-wide humiliation in the wake of the Vietnam War, that strong revisionist rhetoric became a vocal part of American politics.15 In other words, the official American narrative about Hiroshima began to change following our defeat in Vietnam. And although a thorough evaluation would help enrich the arguments in my thesis, I felt it was necessary to restrict my arguments to Hiroshima and the Holocaust in order to remain within the time constraints of writing this paper.

My analysis of how Americans think about Hiroshima begins with the notion that what we commonly accept as history is actually a particular understanding of myth. I argue that history is a plural, open, ever-changing system, whereas this singular form of myth posits an image of an idea whose purpose is to be swallowed whole.16 This is not to suggest that myths do not engage various interpretations. Claude Lévi-Strauss points out that there is not much separation between those narratives that are viewed as history and

15 Over 100,000 American citizens of Japanese descent were ordered into isolated internment camps and

had their homes and businesses confiscated after Pearl Harbor was bombed. No such large-scale action targeted Americans of German or Italian ancestry during the war.

16 Claude Lévi-Strauss writes: “Mythology is static, we find the same mythical elements combined over and

over again, but they are in a closed system, let us say, in contradistinction with history, which is, of course,

an open system.” Claude Lévi-Strauss, Myth and Meaning: Cracking the Code of Culture (New York: Schocken Books, 1995 [1978]), 40. Additionally, Andrew Robinson points out in an article about Barthes

those understood as myth.17 He supports this view of history as an open system by noting that individual myth cells can be rearranged in order to offer new meaning.18 In some respects, this understanding of myth (that of the individual myth cell) equates to the notion of ideology, but myth is more complicated than that.

All narratives cover over the experience of “what really happened,” whether those narratives are considered mythical or historical. Lévi-Strauss suggests that modern aims for historical narratives function similarly to those of mythology: “to ensure that as closely as possible—complete closeness is obviously impossible—the future will remain faithful to the present and to the past.”19 In other words, even modern historical

narratives strive for closure in an attempt to control how we understand the past, present, and future. It is such closure that Benjamin, Bataille, Resnais, Duras, and Barthes contest.

Closure suggests origins. I argue in this thesis that the power of how we remember historical events lies in the telling of its origins. The struggle for closure is also a fight for where to begin the narrative. With this in mind, I include a discussion of creation myths. Creation myths are considered sacred accounts of events found in many

17 Lévi-Strauss,

Myth and Meaning, 34-43. Lévi-Strauss’ insights in Myth and Meaning align with

Bataille’s and Benjamin’s writings in many ways. He points out that new meaning is generated by arranging and rearranging myth cells, not unlike Benjamin’s writings on collections. Also, in the

introduction to Myth and Meaning Lévi-Strauss writes:

I never had, and still do not have, the perception of feeling my personal identity. I appear to

myself as the place where something is going on, but there is no “I”, no “me.” Each of us is a kind

of crossroads where things happen. The crossroads is purely passive; something happens there. A different thing, equally valid, happens elsewhere. There is no choice, it is just a matter of chance.

This passage, in many respects, echoes Bataille’s writings in Inner Experience, where on page 116 Bataille asserts that he does not write from the space of the “I”. Also, in another essay “The Sorcerer’s

Apprentice,” Bataille writes about chance as the guiding factor in life. And finally, Lévi-Strauss’ passage echoes writings by both Benjamin and Bataille where they write about flashes, moments, instants, and ruptures where/when something happens. Ibid., 3-4.

religious traditions. They are often set in what historian of religion Mircea Eliade termed as in illo tempore (“at that time”). Eliade states, “Every origin myth narrates and justifies

a “new situation”—new in the sense that it did not exist from the beginning of the World.”20 All creation myths speak to deeply meaningful questions held by the society

that shares them, revealing a central worldview for the identity of the culture and its individual members. The atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the unrivaled event eradicating life, delivered humanity into the Nuclear Age and helped to solidify the narrative of American exceptionalism as a national Christian myth.21

This discussion of history versus myth extends in this thesis from here into the first chapter, followed by the entire second chapter devoted to the opposition. In the first chapter, history is equated with the idea that something “really happened” at Hiroshima and that America had an investment in censoring, containing, and even distorting those events so that it could create and maintain its myth of America as the bringer of peace.

The reader will likely conclude from my arguments that we are able to know what really happened, and that America has an investment in preventing people from knowing the truth. This assessment, of course, is at odds with the notion that we can never really know what happened (a concept put forward by all of the writers I have included in this thesis). This dialectic performs a kind of estrangement as the thesis progresses to offer readers a more conventional experience of how one would critique historical narratives at the beginning and then a more complex one later.

20 Mircea Eliade, "Magic and Prestige of 'Origins'," in

Myth and Reality, trans. Willard R. Trask (New York: Harper & Row, 1975 [1963]), 21.

The initially presented framework—myth distorts history, or some ways of telling history distort history—is at odds with the overarching mysticism/apophaticism

framework from which this thesis is written. The arguments that I present in the first half of this thesis claim that we can critique certain tellings of history, not because of their formal features (they present themselves as full and complete knowledge) but, rather, because of their content (they fail to disclose what “really happened”). The earlier line of thinking is not within the bounds of the apophatic, but is simply critiquing what certain histories relate. The final chapters, however, attempt to examine what apophatic narratives look like through the films of Alain Resnais, which in many ways exemplify Benjamin’s meditations on history. The apophatic historian would never deny that

something happened—any more than the mystic would deny that the Divine exists, or the trauma survivor would deny that an injury has occurred—but rather that the event, the entity, the experience that we are trying to relate, express, capture in language always exceeds, resists, and shows the folly of our efforts. Apophaticism, then, is a lesson in profound humility, in sharp contrast to the hubris of mastering the past—either as victors or as healers.

There is one additional framework within this thesis that is closely connected to the first two: knowledge versus experience. In the final chapters, I present Bataille’s

critique of knowledge as a problematic form of mastery. Additionally, I offer an example from Hiroshima mon amour that shows how certain tellings destroy the experience by

giving a final meaning by, in Barthes’ language, predicating the sentence. Here, there is

compassion, memory, justice, etc. Again, my arguments in the introduction and first two chapters implicitly trade on a kind of “knowing” relationship to Hiroshima and a call to the reader to know and remember in a way that I critique as the thesis unfolds. As the thesis closes, I argue that what really needs to happen, what our ethical response should be, is that we must find a way to experience the historical event—not as it was

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES xix

CHAPTER 1: SELLING HIROSHIMA TO AMERICA 1

The Story Begins 1

Metaphors of Clouds and the Sun 8

Hersey’s “Hiroshima” 11

Bataille on “Hiroshima” 18

CHAPTER 2: MYTH VERSUS HISTORY 25

Creation Myths and the Power of Naming 26

Origin is the Goal (End) 29

The Role of the Historian 32

CHAPTER 3: NIGHT AND FOG AND HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR 48

Night and Fog 48

Hiroshima mon amour 57

Benjamin’s and Bataille’s Ethics 69

Images of Healing and Closure 74

Hospitals 75

Flowers 78

Hair 85

A Warning against Complacency 87

CHAPTER 4: A PRACTICE OF SEEING 94

Looking without Judging 94

Suffering without Meaning 95

Going Forward 104

LIST OF FIGURES

FIGURE 1: Mushroom cloud, somewhere over Japan, 1945 v

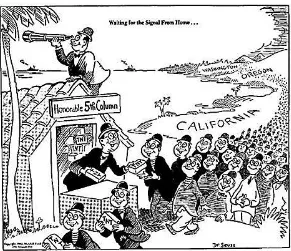

FIGURE 2: Dr. Seuss’ anti-Japanese propaganda cartoon 13

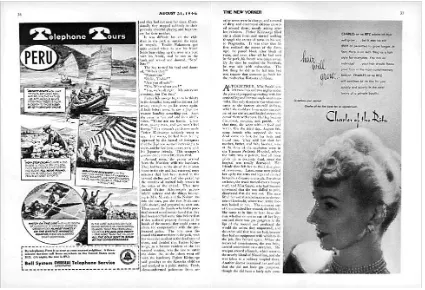

FIGURE 3: The New Yorker’s “Hiroshima” spread 16

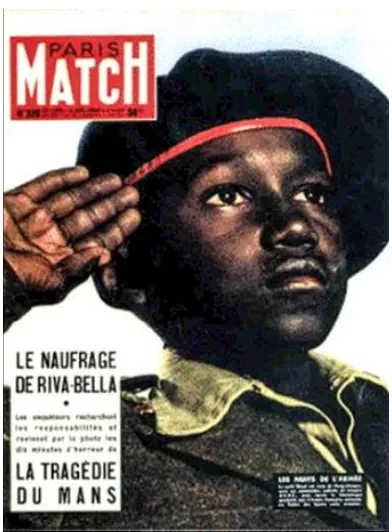

FIGURE 4: The myth of the French soldier 40

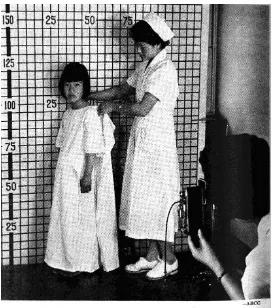

FIGURE 5: Young survivor being measured by a kindly nurse 43

FIGURE 6: The myth of the French police 55

FIGURE 7: Ashes and sweat 58

FIGURE 8: Elle lovingly stroking Lui's hand 77

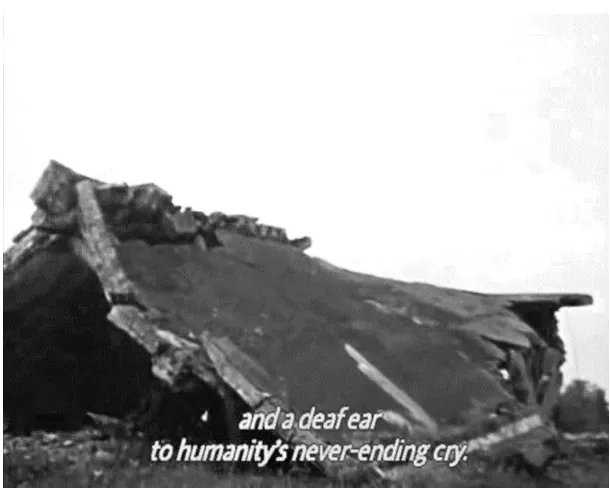

FIGURE 9: Young survivor being consoled by a kindly nurse 80 FIGURE 10: One single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble . . .

The Story Begins

There are many beginnings to many stories told about Hiroshima, as there are with all histories.22 We could begin with the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, an act of aggression that provoked America into finally entering World War II.23 Or we could begin in Hawaii more than a hundred years earlier when New England missionaries earnestly tried to spread their faith to the natives at the same time economic interest was growing for their sugar cane.24 I choose to begin this story

with Truman’s radio broadcast, which informed the world about the first nuclear war. On August 6, 1945, sixteen hours after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima,

President Truman officially proclaimed the event. From the earliest announcement, with one exception, the official narrative of the bombing has been deliberately mystified. This

22 Chimamanda Adachie speaks about the dangers of the single story in her 2009

TEDTalk. She explains, Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person. The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people,

the simplest way to do it is to tell their story and to start with, “secondly.” Start the story with the

arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story.

Chimamanda Adichie, July 22, 2009. "The Danger of a Single Story," TEDGlobal 2009. TEDTalk Video, http://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.html (accessed January 18, 2013).

23This is also the date of Hitler’s infamous Night and Fog Decree which is discussed later in this thesis. 24 The missionaries became powerful sugar planters and politicians.; On Jan. 16, 1893, U.S. Marines landed

in Honolulu without presidential authorization to assist a group of eighteen men (mostly American sugar

farmers) to stage a coup and proclaim themselves the “provisional government” of Hawaii: “Supported by

John Stevens, the U.S. Minister to Hawaii, and a contingent of Marines from the warship U.S.S. Boston, the Committee on Annexation overthrew Queen Lili'uokalani in a bloodless coup on January 17, 1893 and

one exception reveals the President pointedly acknowledging the bombing as an act of vengeance rather than an honorable act to bring the war to a timely end: “The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold.”25

Truman connected military battles with scientific progress: “The battle of the laboratories held fateful risks for us as well as the battles of the air, land, and sea, and we have now won the battle of the laboratories as we have won the other battles.” He also tied progress to our immense monetary investment: “We have spent two billion dollars on the greatest scientific gamble in history—and won.” The atomic bomb, as “the greatest achievement of organized science in history,” was to be a source of great pride for the American people. Truman explains: “The fact that we can release atomic energy ushers in a new era in man’s understanding of nature’s forces.” Americans marshaled the world into the Nuclear Age.26

Truman, however, failed to inform his audience of the atomic bomb’s radiation and its adverse effects.

Both at home and in Japan, American authorities tightly controlled the publication of images and news stories relating to the atomic bombings. U.S. military authorities banned and confiscated all photographs and film footage taken at Hiroshima that

represented anything other than architectural damage (particularly any documentation of injured people). Wilfred Burchett was the first journalist to visit Hiroshima after the

25 Harry S. Truman, "Statement by the President, August 6, 1945."

http://www.trumanlibrary.org/whistlestop/study_collections/bomb/large/documents/pdfs/59.pdf (accessed March 10, 2013).

26As Paul Boyer begins his chapter “Atomic Weapons and Judeo-Christian Ethics,” “The atomic age was opened with prayer.” Following a chaplain’s invocation of divine blessing on the crew of the Enola Gay,

atom bomb was dropped. His Morse code dispatch, which was printed in London’s Daily

Expressnewspaper on September 5, 1945 under the title “The Atomic Plague,” was the

first public report to mention the effects of radiation and nuclear fallout. U.S. censors suppressed a supporting story submitted by George Weller of the Chicago Daily News

and accused Burchett of being influenced by Japanese propaganda. During the U.S. occupation of Japan, and under General MacArthur’s orders, Burchett was barred from

entering Japan.27

General Leslie R. Groves, military head of the wartime atomic bomb project, worked diligently to quickly contain and rebuke any fallout from press attention given to lingering radiation effects. Fearing that reports would create public sympathy for the Japanese, Groves testified before a Senate committee in November 1945 claiming, “[A]s I understand it from the doctors, it is a very pleasant way to die.”28

Groves was part of an evolving campaign by American officials to downplay or deny the fatal and persistent radiation effects inflicted by nuclear weapons. Hiroshima survivors were not the priority; managing public opinion was. Government officials feared that if the truth about radiation effects came to light, the atomic bomb might be categorized with already banned inhumane forms of warfare, such as chemical and biological weapons. Such a finding would limit America’s ability to further test the

27 Amy and David Goodman, "The Hiroshima Cover-Up,"

The Baltimore Sun, 5 August 2005, http://www.commondreams.org/views05/0805-20.htm (accessed March 10, 2013).

28 Sean L. Malloy, "'A Very Pleasant Way to Die': Radiation Effects and the Decision to Use the Atomic

weapon as well as lead to criticism of those who had designed, built, and authorized the use of the atomic bomb against Japan in the first place.29

Throughout the year following the bombings, American journalists under the guiding hand of censors increasingly portrayed Hiroshima and Nagasaki as “symbols of the birth of a new Japan dedicated to rehabilitation, peace, progress, and reconciliation.”30

The underlying message was that Japanese society was progressing steadily under America’s cultivating touch, moving towards a new pacifist outlook that ensured a peaceful future.31

29 Ibid., 518.; The bomb was designed specifically to defeat Hitler, but with Germany’s surrender on May

7th and the threat of further Soviet expansion, the decision was made to drop the bomb on Japan in a grand

theatrical display in order to deter Russia. Steven Poole, in his book Unspeak, writes:

Remember that people killed by terrorism are not the people the perpetrators wish to persuade. They are exemplars, bargaining chips. There is a disconnect between victims and audience; the violence is a warning to people other than those targeted. (The writer Brian Jenkins has summed

up this fact in the catchphrase ‘terrorism is theatre’: a US Army lieutenant colonel went one better, telling a reporter in Baghdad in 2003: ‘terrorism is grand theater.’) Unfortunately this, too, is true of many government actions. Consider the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945...the bombings were designed as an awful demonstration: to instill such fear in the Japanese government that they would surrender. The bomb spoke thus: Give up or there'll be more where this came from. It also sent a powerful message to a secondary audience: Joseph Stalin. On this measure, Hiroshima and Nagasaki are, by many orders of magnitude, the greatest acts of terrorism in history.

Steven Poole, Unspeak: How Words Become Weapons, How Weapons Become a Message, and How That Message Becomes Reality (New York: Grove Press, 2006), 130.

30 Michael J. Yavenditti, "John Hersey and the American Conscience: The Reception of 'Hiroshima',"

Pacific Historical Review 43, no. 1 (1974): 31.

31Japan’s “peaceful future” was instilled through U.S. mandates forcing all military forces to disband. Japan’s postwar Constitution, whose writing was directed by General Douglas MacArthur states:

Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling

international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.

Article 9, The Constitution of Japan (1947). “Carthaginian Peace” comes to mind. The term derives from

peace imposed on Carthage by Rome. After the Second Punic War, Carthage lost all of its colonies, was

forced to demilitarize, pay a constant tribute to Rome, and could not enter war without Rome’s permission.

In turn, Emperor Hirohito was forced to surrender unconditionally, Japan's military was disbanded, Hiroshima was rebuilt into a capitalist economy, and Japan is not allowed to enter war without permission

from U.S. authorities.; Mary: Oh, Charles, I can’t imagine you’re advocating a … Carthaginian peace.

With the bombing of Hiroshima, an act which seemingly ended World War II, America proclaimed itself the leader of the free world. The atomic bomb invested the U.S. with God-like power to take life in the blink of eye.32 America now holds the power

to wipe all life from the face of the earth; this power is the ultimate deterrent. For Truman, the victory in World War II demonstrated American greatness and also invested the United States with the responsibility of ensuring peace and freedom in the postwar world.33 America is the “the greatest nation the sun has ever shone upon.”34 America is the peacemaker and protector of the world. The irrationality of “peace through strength,”

a concept that implies that strength of arms is a necessary component of peace, permeates

32 Upon detonation of the first atomic bomb at the Trinity Test site on July 16, 1945, Robert Oppenheimer, the supervising scientist of The Manhattan Project proclaimed “…now I am become Death [Shiva], the destroyer of worlds...”.

33 Two months after the atomic bombings, Truman stated:

This great development has proven conclusively that a free people can do anything that is necessary for the welfare of the human race as a whole. We created the greatest production machine [developing atomic energy] in the history of the world. We made that machine operate, to the disaster of the dictators. Now then, we want to keep that machine operating. We must keep that machine operating. We have just discovered the source of the sun's power—atomic energy; that is, we have found out how to turn it loose. We had to turn it loose in the beginning for destruction. We are not going to use it for destruction any more, I hope. But that tremendous source of energy can create for us the greatest age in the history of the world if we are sensible enough to put it to that use and to no other. I think we are going to do just that. I think our Allies are going to cooperate with us in peace, just as we cooperated with them in war. . . The greatest age in history is upon us. We must assume that responsibility. We are going to assume it, and every one of you, and all of us, are going to get in and work for the welfare of the world in peace, just as we worked for the welfare of the world in war. That is absolutely essential and necessary. . . [M]ake this country what it ought to be—the greatest nation the sun has ever shone upon.

Harry S. Truman, Address and Remarks at the Dedication of the Kentucky Dam at Gilbertsville, Kentucky October 10, 1945. https://www.trumanlibrary.org/publicpapers/index.php?pid=174&st=&st1= (accessed March 22, 2013). Emphasis added. It is worth noting that Japan is known as “The Land of the Rising Sun.” The characters that make up Japan’s name mean “sun-origin” and its former military flag is the Rising Sun Flag. Japan’s current flag symbolizes the sun with no emanating rays.

American society even today.35 Herbert Marcuse, in the introductory paragraphs of One-Dimensional Man, writes:

Does not the threat of an atomic catastrophe which could wipe out the human race also serve to protect the very forces which perpetuate this danger? The efforts to prevent such a catastrophe overshadow the search for its potential causes in contemporary industrial society. These causes remain unidentified, unexposed, unattacked by the public because they recede before the all too obvious threat from without—to the West from the East, to the East from the West. Equally obvious is the need for being prepared, for living on the brink, for facing the challenge. We submit to the peaceful production of the means of destruction, to

the perfection of waste, to being educated for a defense which deforms the defenders and that which they defend.

If we attempt to relate the causes of the danger to the war in which society is organized and organizes its members, we are immediately confronted with the fact that advanced industrial society becomes richer, bigger, and better as it perpetuates the danger. The defense structure makes life easier for a greater number of people and extends man’s mastery of nature. Under these

circumstances, our mass media have little difficulty in selling particular interests as those of all sensible men. The political needs of society become individual needs and aspirations, their satisfaction promotes business and the commonweal, and the whole appeals to be the very embodiment of Reason.

And yet this society is irrational as a whole. Its productivity is destructive of the free development of human needs and faculties, its peace maintained by the constant threat of war. . .36

Present-day American society’s prosperity and progress are tied directly to the military industrial complex, with nuclear weapons actualizing the high-end expense of the arsenal. At the height of nuclear arms stockpiling in 1966, the United States held over 32,000

35The slogan, “Peace Through Strength,” appeared in the Republican Party platforms of 1980, 1984, 1988, 1992, 1996, 2000, 2008, and 2012. In a recent article about the Republican Party’s search for a way back

to presidential success, the Associated Press quoted Senator Lindsey Graham who stated, “I think it's going

to be difficult to lead the Republican Party without embracing peace through strength, the Ronald Reagan

approach to national security.” Charles Babington, "GOP ponders long list of names, policies, for 2016," The Miami Herald, March 27, 2013, http://www.miamiherald.com/2013/03/27/3309461/gop-ponders-long-list-of-names.html.

36 Herbert Marcuse, "The Paralysis of Criticism: Society without Opposition," in

nuclear warheads and bombs.37 In 2010, President Obama signed the nuclear arms reduction treaty, New START (for Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty), yet according to the U.S. Department of Defense, the Obama administration’s best official estimate still puts nuclear weapons spending at $214 billion over the next ten years.38 Additionally,

Mother Jones reported last year that more than $18 million has been invested in the

election campaigns of lawmakers that oversee nuclear weapons spending. Private companies that produce the main components of the nuclear arsenal “employ more than 95 former members of Congress or Capitol Hill staff to lobby for government funding.”39

William Hartung, who directs the Center for International Policy’s Arms and Security

Project stated that “any effort to downsize the nation’s nuclear force is likely to be met with fierce opposition from the individuals and institutions that benefit from the nuclear status quo, including corporations involved in designing and building nuclear delivery vehicles; companies that operate nuclear warhead-related facilities; and members of Congress with nuclear weapons-related facilities or deployments.”40

Very recently, in an interview with Israeli TV, President Obama stated that he believes Iran is “over a year or so” away from being able to develop a nuclear weapon and that the U.S. will use “all options” to stop it.41 Although the President signed a

nuclear arms reduction treaty less than two years ago, his statements foreclose any

37 "50 Facts About U.S. Nuclear Weapons,"

http://www.brookings.edu/about/projects/archive/nucweapons/50 (accessed March 20, 2013).

38 Russell Rumbaugh and Nathan Cohn, "Resolving the Ambiguity of Nuclear Weapons Costs "

Arms Control Association (June 2012).

http://www.armscontrol.org/act/2012_06/Resolving_the_Ambiguity_of_Nuclear_Weapons_Costs (accessed March 20, 2013).

39 R. Jeffrey Smith, "The Nuclear Weapons Industry's Money Bombs,"

Mother Jones (June 2012). http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2012/06/nuclear-bombs-congress-elections-campaign-donations.

40 Ibid.

41 Devin Dwyer, "Obama: Iran a Year Away From Nuclear Weapon," (March 15, 2013).

pipedreams Americans may harbor for any real nuclear disarmament. Between

congressional lobbyists and potential threats to American sovereignty, we will continue to submit to the “peaceful production of the means of destruction.”42

Metaphors of Clouds and the Sun

The metaphors of clouds and the sun should be considered as we return to the topic of censorship. In the wake of the atomic bombings, the mushroom cloud, that spectacular symbol of wartime triumph and scientific achievement, became the icon by which Americans came to recognize the disaster. For years, the only news images published were photographs of the mushroom cloud (taken by the squadron that dropped the bomb), military maps, and photos of architectural ruin. The distance we held in viewing the events of the bombings effectively masked the death and suffering below. No images of human suffering, injuries, or casualties were allowed to be shown to the world for years after the blasts. The U.S. military censored every journalistic report, and all photographs and filmed evidence of corpses and maimed survivors were confiscated and suppressed. It was not until 1952, when the American Occupation began to withdraw from Japan that photographs of the survivors’ scars emerged in books, newspapers, and magazines.

Historian James Farrell observes that the image of the mushroom cloud presented the bomb as “a new, but natural event, free of human agency.”43 This clouded image

42 These recent development are important to this thesis for a number of reasons. First of all, any present-day nuclear arms development is necessarily tied to America’s earliest decision to invest in and deploy

nuclear weapons in order to maintain our image as world peacemakers. But also, importantly, the

theoretical framework of this paper repeatedly emphasizes that how we view reality in the present moment is inextricably bound to the past. We must be able to see the past as relevant in the present. This point should become clearer as the reader progresses through this thesis.

43 James Farrell, "Nuclear Friezes: Art and the Bomb from Hiroshima to Three Mile Island,"

replicated language articulated by President Truman in his August 6, 1945 address to the nation. By presenting the atomic bombing through statistics (more powerful than

“20,000 tons of TNT”) and side-stepping the bomb’s radiation and its residual effects, Americans (as well as the rest of the world) were led to believe that this new bomb exacted similar—yet more powerful—damage. Other statements in Truman’s public address naturalized the atomic bomb: “It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been loosed against those who brought war to the Far East.” What could be more natural than harnessing energy

from the sun?

In an essay written before Hiroshima, Georges Bataille envisioned the sun split into two parts: the light-giving, rational, never-to-be-looked-at-directly share and the elevated, sacrificial, source of destruction and madness that blinds anyone who dares to stare into its awesome power.44 He claims that we can scrutinize the light-giving source only by looking at its reflection, never directly at its radiance. The human point of view of the sun is equated to the concept of noon, with the sun in its highest elevation.45 The

noonday sun (the one that cannot be looked at) represents the ideal. It is considered perfectly beautiful. On the flip-side, the source of this blinding energy is considered horribly ugly.46

Bataille compares this dualistic sun with two mythological figures: “In

mythology, the scrutinized sun is identified with a man who slays a bull (Mithra), with a vulture that eats the liver (Prometheus): in other words, with the man who looks along

44 Bataille grapples with this concept throughout his writings, most notably in his novel

Le Bleu du Ciel (The Blue of Noon) and its philosophical counterpart L'expérience intérieure (Inner Experience).

45 Bataille, "Rotten Sun," in

Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939, 57.

with the slain bull or the eaten liver.”47 A person (or one’s actions) can at once be

identified with the acclaimed Mithra or with the disgusting vulture. Bataille asserts that “the summit of elevation is in practice confused with a sudden fall of unheard-of

violence.” That is to say, there is little, if any, separation between reaching such an apex and enacting such violence.48

Icarus, for Bataille, is a telling example (connecting both the sun and the fall). He writes: “it clearly splits the sun in two—the one that was shining at the moment of

Icarus’s elevation, and the one that melted the wax, causing failure and a screaming fall when Icarus got too close.”49 This vision can be applied at once to America’s act of

dropping the bomb on Hiroshima and simultaneously to her meteoric rise to power on the world stage in its aftermath. Those at the helm of government would have us reflect only upon the “benefits” afforded us from this act and look away from the power that was

unleashed on the now suffering other. Looking too closely could bring our own fall. American censors invested in shrouding the bombs’ effects on humans, but this drought of information made people hungry for personal narratives of the tragedy. The editor of The New Yorker, a progressive liberal magazine, consigned a leading journalist

to travel to Japan to interview survivors and report his findings for the one-year anniversary of the bombings.

47 Bataille, "Rotten Sun," in

Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939, 57.

48 As a sidenote, I would add that in other writings, Bataille made clear that sacrifice does not necessarily

equate to a violent, bloody act. I assume that Bataille is making a similar move here. He very well could be pointing to an inner experience.

49 Bataille, "Rotten Sun," in

Hersey’s “Hiroshima”

On August 31, 1946, The New Yorker dedicated its entire issue to eyewitness

accounts of the Hiroshima bombing one year earlier.50 John Hersey, a Pulitzer

Prize-winning American writer and journalist, spent several weeks in Japan interviewing survivors. From the start, his intention was to convey his findings through personal accounts written in an objective manner. He did not want to narrate; rather he wanted the stories to speak for themselves.51 “Hiroshima” was originally written to be published in four installments, but after reading the story, the editor decided to devote the entire issue to the text.52

“Hiroshima” revolves around the experiences of six survivors over the course of the first year following the atomic bombing. The only non-Japanese individual of the sextet, a Jesuit priest (Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge), was German. The five Japanese protagonists consisted of a young Red Cross hospital surgeon (Dr. Terufumi Sasaki), a doctor with a private practice (Dr. Masakazu Fujii), a female clerk (Toshiko Sasaki), a Methodist clergyman (Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto), and a tailor’s widow (Mrs. Hatsuyo

Nakamura). For some time after the bomb had fallen, none of them knew exactly what had happened, remaining unaware that the life they knew had come to a horrific end.

50 The entire issue of

The New Yorker, including original advertisements, can be accessed online: John Hersey, "Hiroshima," The New Yorker, August 31, 1946. http://archives.newyorker.com/?i=1946-08-31#folio=CV1 (accessed February 7, 2013).

51Years later in an interview, Hersey said, “The flat style was deliberate, and I still think I was right to

adopt it. A high literary manner, or a show of passion, would have brought me into the story as a mediator;

I wanted to avoid such mediation, so the reader’s experience would be as direct as possible.” Paul S. Boyer, By the Bomb's Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age (New York: Pantheon, 1985), 208.; Hersey's claim to provide an account of the bombing without mediation suggests that historical events exist outside representation.

“They had been chosen by chance, or destiny, or as two of them would have put it, by

God.” 53 Slowly, over time, they awakened to the magnitude of the catastrophe that had,

in a flash, annihilated nearly all their known world.

Hersey carefully selected the eyewitness accounts that he felt would best affect his target American audience. It is no accident that the chosen six survivors enjoyed higher economic status and were better educated than many other Hiroshima residents. Following many years of American anti-Japanese propaganda, in which cartoons, posters, and advertisements presented Japanese men as sinister, bloodthirsty villains (even going so far as to portray Japanese soldiers as worms, snakes, and rats), Hersey assigned himself the crucial task of humanizing the victims by developing characters with which the average American could identify.54 For example, Reverend Tanimoto, who “had studied theology at Emory College, in Atlanta, Georgia,” speaks “excellent English,” and dresses “in American clothes.”55 Moreover, a white Jesuit priest and an

American-educated Methodist minister would appeal to a predominantly white middle-class Christian readership. Hersey’s selection of two overtly Christian characters (one

Catholic, one Protestant) out of six may seem excessive to anyone unaware that Hersey’s

53 Publisher’s note. John Hersey,

Hiroshima (London: Penguin Books Ltd., 1946), vi. Emphasis added.

54 FIGURE 2: Dr. Seuss’ anti-Japanese propaganda cartoon exemplifies common racist caricatures

published in American newspapers and magazines before and during World War II. This particular cartoon was published in the February 13, 1942 edition of the New York newspaper PM. (Ernest Hemingway and future Speaker of the House Tip O'Neill join Dr. Seuss as notable contributors to PM.) Japanese Americans are depicted in this image as a subversive fifth-column, gathering to pick up explosives which they will no doubt use in attacks within America. A few days after this cartoon was published, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which mandated the internment of Japanese American citizens. This is not to suggest that this cartoon incited the order. It does, however, stand as a primary example of political cartoons of its time. A collection of anti-Japanese propaganda can be found online at

http://www.authentichistory.com/1939-1945/2-homefront/3-anti-jap/index.html.

55 John Hersey,

own parents had been Protestant missionaries for the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in China.56

FIGURE 2: Dr. Seuss’ anti-Japanese propaganda cartoon57

“Hiroshima” became particularly important for raising American awareness of the

after effects of the bombings, especially in light of the abounding censorship. Michael Yavendetti writes:

More vividly than all previous publications combined, “Hiroshima” suggested for Americans what a surprise atomic attack could do to an American city and its inhabitants. . . . The numerous post-bombing photographs and newsreels of Hiroshima and Nagasaki made them look like any other war devastated city. Americans could comprehend that one bomb had caused the damage, but the

56 James Guimond,

American Photography and the American Dream (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 30.

57 Originally printed in the February 14, 1942 edition of PM newspaper. Theodor Geisel, better known as

Dr. Seuss, created The Cat in the Hat in response to the May 24, 1954, Life magazine article by Hersey, titled "Why Do Students Bog Down on First R? A Local Committee Sheds Light on a National Problem: Reading." In the article, Hersey was critical of school primers and specifically called out several writers by name to address the issue, including Dr. Seuss. Ruth K. MacDonald, Dr. Seuss (Boston: Twayne

media did not fully demonstrate that Hiroshima and Nagasaki were qualitatively different from other kinds of wartime catastrophes.58

“Hiroshima” was published several years before photographic images showed any evidence of physical suffering, becoming the primary means for the American public to envision Hiroshima’s horrors.

By the end of the story, the reader most likely would have concluded that America liberated the Japanese. The effects of the bomb are denounced, but Hersey’s prose never questions the end itself. Underlying any outrage over the bombing rests a sense of gratitude for the American liberators: just as America ostensibly freed the Europeans from the lethal grip of the Nazi death machine, she also freed the Japanese from their militaristic government. But along with America’s brand of democratic freedom comes the subordination of individual rights to the overall “good” of the State.59

But Americans were being sold more than just a story about bombing victims and American generosity. Postwar America was caught up in its new-found prosperity and, with it, heightened consumerism. “Hiroshima” was published as the lone article of the

The New Yorker’s August edition, but regular advertising appeared as usual. This issue

aroused fear, anxiety, and guilt about the bomb, while simultaneously directing reader’s emotions toward consumer products that acted to both alleviate those feelings and reify middle-class sensibilities.

In this atmosphere of commodified good will, to many of The New Yorker's

liberal readers, encountering a critical account of the bombing of Hiroshima among advertisements for ocean liners, Fords, and single-malt Scotch Whiskey

58 Yavenditti, "John Hersey and the American Conscience: The Reception of 'Hiroshima'," 37, 46-47. 59 Christopher D. Craig, "The New Yorker's 'Hiroshima': Tiffany Diamonds, Caribbean Cruises, and the

may have seemed as natural as discussing the dangers of Western Imperialism while lying on the sandy beaches of the Bahamas.60

Christopher Craig argues that by publishing “Hiroshima” in The New Yorker, the article

along with its advertisements “whose wide range of products symbolizes freedom of choice and confirms the benefits of living in a democratic society” subtly defend the bombing even as it opposes it in order to offer readers a hopeful resolution to the bomb’s devastation.61 The ads themselves mystify the violence inherent in their product’s construction. The consumer who purchases the $8,500 diamond bracelet never sees the blood spilled in the African mines, nor is the cruise ship passenger aware of the

longstanding “subjugation and exploitation orchestrated by the United States in the Caribbean, South and Central America, and the Pacific.”62 These advertisements

60 Ibid.

61 Ibid.; FIGURE 3 features an ad for hair stylist Charles of the Ritz, which prominently displays the tagline “hair will grow.” This invitation for female readers to be adventurous and try a new hairstyle is interesting

both in relation to the repeated references in Hersey’s text about radiation’s effects on hair and also to

Hiroshima mon amour’s female protagonist’s madness (which will be discussed later in this paper). It begins on page 48 of The New Yorker article where Mrs. Nakamura, who had seemingly escaped all injury from the blast, began losing her hair at an alarming rate, until she was completely bald. On page 52, her loss of hair is equated to Japanese hatred for Americans: “[W]ithin a short time after [Mrs. Nakamura’s]

hair had started growing back again—her whole family relaxed their extreme hatred of America.” Finally,

on page 56, the reader is exposed to descriptions of radiation sickness: “Dr. Sasaki and his colleagues at the

Red Cross Hospital watched the unprecedented disease unfold and at last evolved a theory about its nature. . . [Stage two's] first symptom was falling hair. Diarrhea and fever, which in some cases went as high as 106, came next. Twenty-five to thirty days after the explosion, blood disorders appeared: gums bled, the white-blood-cell count dropped sharply, and petecbiaeappeared on the skin and mucous membranes.” Modern readers of this New Yorker issue will find these ads to be in poor taste, but audiences in 1946 probably would not have even noticed a disconnect.

62 Ibid.; The Tiffany and Co. diamond and ruby bracelet for $8,500 and matching brooch listed for $3,750

exchange the violence inherent to the production of these commodities with notions of prosperity and privileged well-being.63

FIGURE 3: The New Yorker’s “Hiroshima” spread

The magazine issue quickly sold out and was reprinted by the millions. Hersey and The New Yorker allowed reprints with two conditions: that all profits go to the Red

Cross and that the article must not be abridged.64 ABC (the American Broadcasting Company) aired four special commercial-free half-hour broadcasts of the text in

63 In a more overt advertisement for Federal Union, Inc., marketers speak directly to the threat of a nuclear attack on U.S. soil on page 48: “As long as you and I can remember, a statue in New York Harbor has been

carrying the torch for these United States. . . but now—in this atomic age…a bomb could destroy the statue…and Liberty, too. We can no longer afford to leave it to a statue to carry that torch. . . Why not help

secure peace and freedom. . . under a world government.” (http://archives.newyorker.com/?i=1946 -08-31#folio=048). This ad in particular reifies the reader’s assessment that liberating the Japanese is for the

greater good of the entire world.

September, followed soon after by similar international broadcasts. The book was published before the end of the year and free copies were distributed to all members of the Book-of-the-Month club.65 The success of the story at home and abroad indicated

that the public was eager to learn about the human impact of the bomb; people were ready to know the survivors’ experiences.

Hersey’s work influenced many writers in different contexts. The narrative style of the New Journalism movement of the 1960s was directly influenced by Hersey’s “Hiroshima.” Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and Norman Mailer’s The Armies of the Night are two such examples of combining historical facts with a novel’s fictional style.

Also, publishing “Hiroshima” in The New Yorker elicited a corresponding response from

Truman’s Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson. “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb” was published in Harper’s Magazine in February 1947 as a rebuttal to mitigate any sympathies the American public had generated since the publication of “Hiroshima.”

Whereas Hersey infused human qualities in the narratives of the victims, our former enemies, Stimson attempted to humanize the decision-makers behind the bomb in order to shift sympathetic attention back to American leaders. His assertions for the decision to drop the bomb remain in the collective narrative even today: “In order to end the war in the shortest possible time and to avoid the enormous losses of human life which

otherwise confronted us,” no other decision could ethically be made.66 On the flip-side of responses, Georges Bataille also published a response to Hersey’s account in February 1947.

65 Jon Michaud, "Eighty-Five from the Archive: John Hersey,"

The New Yorker (June 8, 2010). http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/backissues/2010/06/eighty-five-from-the-archive-john-hersey.html (accessed February 22, 2013).

66 Henry L. Stimson, "The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb,"

Bataille on “Hiroshima”

Bataille’s essay, “Concerning the Accounts Given by the Residents of Hiroshima,” is a meditation on Hersey’s book Hiroshima.67 In this piece, Bataille

contemplates the “laughable ignorance” exhibited by the survivors of the catastrophe: “dazzled by an immense flash—which had the intensity of the sun and was followed by no detonation,” the victims learned nothing from their immediate experience. In terminology used elsewhere in Bataille’s writing, the survivors experienced an event of non-knowledge. They were traumatized, unable to form objective assessments of their immediate experience. He notes that “throughout the day the disaster was attributed to ‘a Molotov flower basket,’ the Japanese name for the cluster of bombs that disperse

themselves as they fall.”68 In other words, the survivors had no point of reference for the

atomic bomb. The entire world learned of the atomic bombing before the residents of Hiroshima.69 Bataille, at this juncture, illustrates the significance of this divergence: For Truman and the rest of the world, the atomic bomb heralded a new age; but for the surviving victims, no such leap into the future had occurred.

Bataille commends Hersey’s journalistic reporting, pointing out that by providing the fragmented isolated eyewitness accounts, these recollections are reduced to the “dimensions of animal experience.”70 They are, in a broad sense, the ruins of the

67Bataille’s essay was first published in

Critique 8-9, January and February 1947 under the title, “A propos

de récits d’habitants d’Hiroshima.”

68 Georges Bataille, "Concerning the Accounts Given by the Residents of Hiroshima," in

Trauma: Explorations in Memory, ed. Cathy Caruth (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 223-224.;

“Molotov flower basket” is referenced several times in chapter 2 of Hersey’s book. 69Bataille comments on this very idea in his chapter “Angel” in

Guilty where he illustrates how schoolchildren after him will know more about the war than he does. Knowledge, like history, is

incomplete. Georges Bataille, "Angel," in Guilty, trans. Bruce Boone (Venice, CA: The Lapis Press, 1988 [1939-40]), 26.

70 Bataille, "Concerning the Accounts Given by the Residents of Hiroshima," in