Do Incumbents’

Mergers Influence

Entrepreneurial Entry?

An Evaluation

Sumit K. Majumdar

Rabih Moussawi

Ulku Yaylacicegi

This analysis has evaluated the impact of mergers on new entrepreneurial firm entry in the territories of firms making up the local exchange sector of the United States telecommuni-cations industry. An analysis of first and second mergers undertaken by the local exchange companies has revealed that where mergers occurred there was significantly lower entre-preneurial entry. The results have implications for policy, since the approval of mergers has been shown to lead to lower entrepreneurial entry where mergers occur, and the approval of mergers may serve to impede entrepreneurship. Hence, greater thought should be given to merger approvals so that entrepreneurship and the process of economic growth are not compromised as a result.

Introduction

In the United States, numerous incumbent local exchange carrier (ILEC) mergers have taken place in the telecommunications sector. These ILEC mergers were approved by the Department of Justice and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Their approvals have been consequential. One such consequence has been the consolidation of the local exchange sector. Simultaneous institutional changes have brought the presence of horizontal competition in ILECs’ territories. The landmark Telecommunications Act of 1996 encouraged entry of new entrepreneurial firms to become horizontal competitors in the franchised territories of the ILECs.

This study evaluates the impact of the various approved mergers on new entrepre-neurial firm entry in ILECs’ territories in the United States. The analysis conducted strips out the impact of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. As a major institutional change, impacting industry structure, this legislation exogenously encouraged entry by potential competitors, as meant to by lawmakers. Controlling for other factors, the issue evaluated is whether after the approved mergers undertaken by the ILECs, there has been entry of

Please send correspondence to: Sumit K. Majumdar, tel.: 972-883-4786, e-mail: Majumdar@utdallas.edu, to Rabih Moussawi at Rabihm7@gmail.com, and to Ulku Yaylacicegi at yaylacicegiu@uncw.edu.

P

T

E

&

1042-2587

new entrepreneurial firms in their territories. This is a key question, linking merger approvals and new entrepreneurial firm entry, at the heart of important debates in the public policy and entrepreneurship literatures.

A sizable portion of contemporary entrepreneurship research lies at the intersection between strategic management and public policy (Levie & Autio, 2011; Minniti, 2008). Entrepreneurs are considered the prime drivers of economic progress (Hughes, 1986; Leff, 1979), as they pursue opportunities, create competitive advantage (Ireland, Hitt, & Sirmon, 2003), and contribute to economic growth. Yet, they are subject to considerable contextual influences (Davidsson & Wiklund, 2001; Shane, 2003; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). Social and political contexts influence entrepreneurs’ attitudes, allocation of efforts, levels of resources to be mobilized, and dictate the constraints impinging on establishing an enterprise (Bowen & De Clercq, 2008; Harper, 1998; Martinelli, 2004). Consequently, the policy context materially impacts the nature, direction, rate, and extent of entrepreneurship (Welter & Smallbone, 2011).

In the last decade, a stream of literature has emerged suggesting that institutional factors prominently exercise contextual influence (Boettke, 2001; Wennekers & Thurik, 1999). Institutional factors order reality by providing meanings for actions (Thornton & Ocasio, 1999); but they also influence business outcomes (Meyer & Rowan, 1991) across regions (Reynolds, Miller, & Maki, 1995). Specifically, legal and regulatory institutional decisions, as described by North and Thomas (1973) and Olson (1982), materially influ-ence entrepreneurs’ perceptions, behavior, and performance (Baumol, 1990; Capelleras, Mole, Greene, & Storey, 2008; Olson, 1996).

Entrepreneurial decisions are influenced by institutional decisions because such deci-sions directly impact the generation and distribution of returns to entrepreneurship (Autio & Acs, 2010; O’Brien, Folta, & Johnson, 2003). Institutional decisions define rules of the game, provide a framework to guide activity, remove uncertainty, ensure action predictability, and reduce transactions costs (North, 1990), and the institutional decision-making environment can create or destroy entrepreneurship within a country (Aldrich &

Wiedenmayer, 1993).1

A critical institutional factor affecting entrepreneurial behavior has been public policies and regulations with respect to entrepreneurial firm entry (Djankov, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, & Shleifer, 2002). The entrepreneurship (Davidsson, Hunter, & Klofsten, 2007; Davis & Henrekson, 1999; Sørensen, 2007) and allied literatures (Audretsch, van Leeuwen, Menkveld, & Thurik, 2001; Bertrand & Kramarz, 2002; Klapper, Laeven, & Rajan, 2006) evaluates how entry of new firms is affected by insti-tutional factors. The broad finding has established that costly regulations, leading to higher entry costs, dampen entrepreneurial behavior and stifle growth.

In many sectors, mergers of large firms are regulated by competition policy authori-ties. Public policy decisions, as to whether to allow mergers between large incumbent firms, have a bearing on the nature of the competitive playing field. Approval of such mergers can promote or deter new firm entry. A small theoretical literature, aimed at developing policies as to whether mergers should be approved or not, evaluates the impact

of mergers on firm entry. But, have mergers, most requiring approval by competition authorities, triggered new entrepreneurial firm entry? Or, have mergers acted as entry deterrents for entrepreneurial firms? These are germane issues, at the heart of the

insti-tutional change and entrepreneurial behavior literature, we know little about.2

The conceptual literature, related to the topic of mergers and firm entry, does not contain clear propositions. Stigler (1950) had suggested that large incumbents’ mergers would trigger new firm entry. Therefore, mergers ought to be approved. This has been the dominant logic behind the policy of merger approval in the United States (Coate, 2008). Yet, mergers between firms in an industry sector create important entry barriers (Baker, 2003), and mergers can be used as an entry deterrence strategy to thwart entrepreneurial firms’ entry. Thus, an institutional decision by-product, to permit large incumbents’ mergers, can be the slowdown of entrepreneurship in an economy.

While several theoretical analyses (Cabral, 2003; Marino & Zabojnik, 2006; Pesendorfer, 2005; Spector, 2003; Werden & Froeb, 1998) have generated conflicting results, a key analysis has established that mergers did not induce new entrepreneurial firm entry (Werden & Froeb). Therefore, approvals for large firm mergers should be sparsely given. Yet, U.S. courts have rejected challenges against the approvals of large firm mergers. They have approved numerous recent large firm mergers on the grounds that contemporary markets are contestable, and new entrepreneurial firm entry triggered by mergers will constrain any subsequent anticompetitive effects (Davidson & Mukherjee, 2007).

But, have these grounds for institutional merger approbation been valid? In spite of the considerably important role that mergers play in shaping industry structures, competi-tive conditions and entrepreneurial behavior, little evidence exists about whether new firm entry has occurred after mergers. Empirical analysis of new firm entry, after the approval of incumbent firms’ mergers, is negligible. Just one study (Berger, Bonime, Goldberg, & White, 2004) has evaluated the dynamics of approved and consummated mergers on new firm entry, for the banking industry. A positive result was noted. The lack of evidence on the topic is a major lacuna, given the role that mergers are assumed to play in engendering new firm entry. This analysis adds to the corpus of evidence.

Impact of Mergers on Entry

Early Thinking on Mergers and Entry

It is useful to articulate a simple model explaining the link between mergers and entry. There are contending perspectives on the impact of mergers on entry. The literature on entry barriers commenced with Bain (1956). Such entry barriers were engendered by advantages incumbents held over entrants, and allowed prices to be above competitive levels. The main entry barriers were scale economies, capital requirements, product differentiation, and cost advantages. These acted to exclude new firm entry.

Further developments of the theory of entry barriers owed much to the debates between Bain (1956) and Stigler (1968). Stigler (1950) changed the focus of analysis from profits to costs. He defined entry barriers as the costs of production likely to be borne by new entrants, but not incumbents. With respect to post-merger new firm entry, provided such entry was free and costless, the anticompetitive effects of mergers would be wiped out by new competition (Stigler). Thus, Stigler recommended approving incumbents’

mergers because new firm entry would control incumbents’ possible punitive actions.3The key entry barriers in the anti-interventionist Stigler school of merger policy thought were other regulations, possession of patents, and control of essential inputs (Coate, 2008). These policy barriers, and not merger approvals, were the institutional reasons keeping new firms out of incumbents’ territories.

In later writing, Stigler (1968) stated that incumbent firms’ capabilities would lead them to create entry barriers. These entry barriers were organizational and outcomes of incumbents’ superior performance. Firms’ actions led them to achieve superior market and resource positions protected by entry barriers. While such incumbent-created barriers might deter entry, from a policy point, incumbents’ mergers could be approved since

barriers were endogenously created.4

The literature is unclear as to why mergers are entry inducing or deterring. Hence, further conceptualization is useful. Mergers are typically driven by the search for syn-ergies and scale economies (Brush, 1996; Farrell & Shapiro, 2001; Pitofsky, 1999). A

desire for cost savings typically lead incumbent firms to merge.5

By announcing and consummating such mergers, the merging firms signal that their cost structures have been uncompetitive. In a dynamic technological environment, where cost structures keep shifting consistently downward, because of innovations and learning economies, entry motivations would exist because new firms’ cost structures could be lower than that of incumbents.

Such newly entering firms would be more efficient than older incumbents because of the possibility of larger and older firms becoming inefficient with age (Hill & Kalirajan, 1993; Nguyen & Reznek, 1991; Schmalensee, 1989). These new firms would be able to supply consumers with items at lower prices. In addition, incumbent firms could also be interested in acquiring the efficient entrants in order to augment sources of cheap supply. Thus, incumbents could signal to an entrant that a future sellout, by merger, to an incumbent would be a viable exit strategy increasing the expected net present value of entry. Hence, positive entry of new entrepreneurial firms would occur after incumbents’ mergers were approved and consummated.

Alternatively, incumbents’ mergers could negatively affect entry. Generally, numerous factors would increase the length of time for new entry to restore a competitive equilib-rium after structural adjustments such as mergers (Posner, 1976). An entry deterrence strategy adopted by incumbents could be mergers. The possibilities of delays in the subsequent long run structural adjustment process could signal to entrants the incumbents’ possession of potential aggressive intents as well as resources to wait for favorable

3. Stigler (1950) assumed that potential new firm entry would exercise competitive pressures on incumbents to not engage in anticompetitive acts. Entry by new firms was a disciplinary device signifying the dynamics of a working competitive economy.

4. Extending the Stigler (1950, 1968) point of view, Williamson (1968) suggested that antitrust concerns arising from mergers could be obviated if merger cost savings were larger than allocative inefficiencies. Even small levels of cost savings could offset distortions arising from the exercise of market power. These would lead to net welfare gains. Williamson, therefore, suggested that merger approvals be given even if new firm entry were to be foreclosed. The critical assumption was the generation of dynamic efficiencies as a result of mergers. These dynamic efficiencies would arise because of the harnessing of capabilities (Stigler) and the acquiring of scale and scope economies via mergers. Capability harnessing and generation of dynamic efficiencies would make the allocative inefficiencies that were generated (Bain, 1956) less onerous. Dynamic efficiencies would make the merged incumbent firms formidable competitors, leading to less new firm entry as the outcomes of incumbents’ retaliatory threats could be negative.

conditions. Having bought time, incumbents could deter entry by preemption of entrants’ independent purchases of target firms. A subsequent impact would be an increase in the probability of post-merger incumbents’ punitive reactions, say by price cutting or other measures, thus stifling the entrant in an early stage of existence in the sector. This contingency could also deter entry.

Later Development of Ideas6

Additional ideas have sharpened the relationships between mergers and new firm entry. Incumbent firms create entry barriers by large investments in assets that become sunk (Gilbert, 1989). A firm with large sunk costs would, in the face of likely entry, engage in strategic deterrence activities (Salop, 1979) to protect its position. An incumbent could protect itself by merging with others, creating a large sunk cost pool, and making the replication of resources by entrants difficult. A committed new entrant would have to enter at a large scale to match merged incumbents in size. If a new firm entered at a suitable scale, the large output volumes generated by the incumbent(s) and the new entrant

together would depress prices and make a new entrant’s finances unviable.7

Sunk costs, as ancillary barriers, would reinforce the deterrent effects of mergers by

creating higher uncertainty levels8 and magnify risk (Carlton & Perloff, 1994). Thus,

incumbents’ mergers would act as entry deterrents. If entry required large sunk costs,9the

6. The contemporary industrial organization literature does not evaluate entry incentives,per se.It simply takes entry by new competitors as given. There are very few mentions in the literature about incumbents’ creation of entry barriers. The aim of contemporary economic analysis is to evaluate the consequences of entry on merger outcomes. Davidson and Mukherjee (2007) suggest that, with moderate cost synergies, mergers of a small number of industry participants are beneficial. Werden and Froeb (1998) establish that, in the absence of synergies, a merger followed by new entrepreneurial firm entry is unprofitable for the merging firms and to be profitable mergers must lead to raised prices. Spector (2003) shows that a profitable merger, where synergies are absent, raises price even if new entrepreneurial firm entry occurs. Cabral (2003) restates ideas suggesting post-merger cost efficiency possibilities will decrease entry likelihood. Marino and Zabojnik (2006) reverse the dynamics to suggest that if entry is easy, and entrants exert competitive pressure on the merging firms, then merging firms will be driven in their merger decisions by a search for efficiency as opposed to being driven by motivations to increase market power. Pesendorfer (2005) shows that after an initial merger, if new entrepreneurial firm entry occurs, a strategy for incumbent firms to cope with new competitors is to buy them up. If entrants can be further acquired, in a series of sequential mergers, then the initial merger decisions may be profitable. Such predatory acquisitions by incumbents could have two effects on entry. A number of entrepreneurial firms might enter, hoping to be bought by the incumbents so that founders could cash out quickly. Larger entrants might resist entry if being acquired was a possibility that would cause loss of entrepreneurial or managerial independence.

post-entry risk of large losses would be high. Since entrepreneurs, with potentially major capital constraints, would be risking their limited amounts of equity, institutionally approved large firm incumbents’ mergers would magnify the risks to the future cash flows of entrants. These risks would enhance the impact of sunk costs and uncertainty for entrepreneurs. In entrepreneurs’ perceptions, the risks of large losses, possibilities of business failures after entry, and the decline of post-entry firm value would be high enough to preclude entry in the face of large incumbent firms’ mergers. Hence, a general working presumption, to ground subsequent analysis, is that mergers of incumbent large firms in a sector will deter entry by new entrepreneurial firms.

Context Evaluated

Institutional Changes

Given the issue being examined, the context is very important. The industry had been historically competitive, with new firm entry, but evolved into a regulated monopoly. The last 20 years have seen fundamental structural changes in the telecommunications sector. After the issue of a Modification of Final Judgment (MFJ) in 1982, and pursuant to a consent decree, in 1984 AT&T divested its local telephone companies, called the Bell

Operating Companies (BOCs), and retained long distance services.10Twelve years after

the 1984 divestiture, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 again recast industry structure

to make it competitive (Cave, Majumdar, & Vogelsang, 2002).11This structure-changing

legislation was intended to bring competition into a sector monopolized by ILECs. Hence, the impact of this legislation would be to induce entry in incumbents’ markets.

Competitive local exchange carriers (CLECs) were defined as incumbents’ rivals, or firms that entered local phone markets after divestiture. The Telecommunications Act of 1996 and the FCC Report and Order of 1996 led such firms to enter the local telecom-munications market in three ways. First, CLECs could purchase a local service at

whole-sale rates and resell it to the end users. These CLECs were classified asresellers. Second,

they could lease various unbundled elements of an incumbent’s network through

coloca-tion. These CLECs were classified asservice providers. Third, they could set up networks

asfacilities-based competitors.

The emergence of new firms was profound (Loomis & Swann, 2005), based on trends noted for the late 1990s and early 2000s (Koski & Majumdar, 2002). Accessing the incumbent’s network operations as a reseller was a minor way to enter local markets. Only 1.7% of the total lines installed by ILECs were subject to reselling at the end of the 1990s. Even less leasing of unbundled local loops took place. Only 0.2% of the ILECs’ loops were leased. Conversely, the CLECs concentrated their efforts on network building to provide infrastructure-based competition. Between the mid and late 1990s, the CLECs

10. In 1984, 22 BOCs were in existence, and 161 local access and transport areas (LATAs) were created. The BOCs were permitted to carry calls originating and terminating in one LATA.

increased their investments in fiber from 0.4 to 3.1 million miles. Incumbents increased their fiber network size from 9 to 16.1 million miles in the same period. The proportion of CLECs’ fiber miles to ILECs’ fiber miles had risen from 4.2 to 16.1%. Thus, entering facilities-based CLECs could be effective competitors to the ILECs (Koski & Majumdar, 2002).

Mergers in the Sector

The detailed flow of mergers and their approvals in the sector are described next. In 1984, with the break-up of the old AT&T, the sector consisted of seven Regional Holding Companies (RHCs), which between them owned 22 stand-alone Bell Operating Companies (BOCs); an example of one was New England Telephone, which was owned by NYNEX, the relevant RHC. There were five other such groupings, namely Central Telephone, Continental Telephone, GTE, Southern New England Telephone, and United Telephone, and two large independent companies, namely Cincinnati Bell and Rochester Telephone. In total, these groupings owned several ILECs. Of these, just over

40 accounted for well over 95% of the lines.12

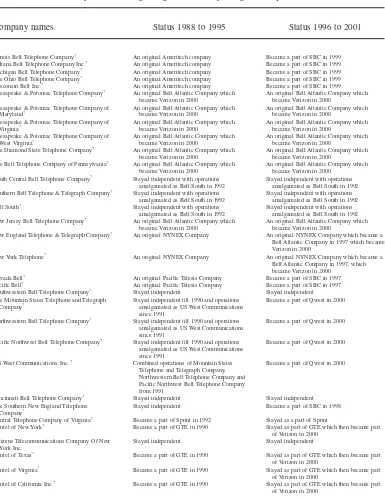

Table 1 lists each company’s situation, over the period analyzed, in terms of owner-ship status and merger activity. In the early 1990s, several RHCs amalgamated their separate stand-alone local exchange companies. Two examples follow. In 1991, the operations of Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Company, Northwestern Bell

Telephone Company, and Pacific Northwest Bell Telephone Company were combined

to form US West Communications. In 1992, the amalgamation of South Central Bell Telephone Company and Southern Bell Telephone and Telegraph Company operations, as Bell South, took place. These companies were regulated, by state agencies, in specific territories they operated in.

Simultaneously, several non-RHC groupings, which did not have adequate resources, or were territorially disparate, were acquired by other groupings. Thus, Continental merged its companies, such as Contel of California, Contel of New York, Contel of Virginia and Contel of Texas with GTE. These mergers occurred in 1990. Thereafter, the operating companies belonging to United were acquired by Sprint in 1991, and the Central Telephone Company was acquired by Sprint in 1992.

A spate of mergers occurred in the mid 1990s. The landmark Telecommunications Act of 1996 opened the local exchange market to entry by competitive local exchange carriers. This motivated a series of initial performance-enhancing mergers among unattached RHCs. For example, Pacific Telesis, under financial strain in its California operations, was acquired and merged with Southwestern Bell Corporation (SBC) in 1997. SBC also acquired Southern New England Telephone (SNET) in 1998. In addition, intermodal cable competition emerged. The erstwhile AT&T, the long-distance company, had purchased several cable companies, such as TCI, Media One, and Lenfest by 1999. It had also purchased the downtown Boston assets of Cable Vision. All of these had cost well over $100 billion. The AT&T cable business could provide very substantial competition to the incumbents.

Several RHCs began acquiring other RHCs or other groupings. Ameritech was acquired by SBC in 1999 so as to acquire the financial scale to be a player with major presence in all local exchange markets across the United States. Then, in 2000 GTE was

Table 1

Status of Firms and Merger Activity in the Local Exchange Sector of the U.S. Telecommunications Industry

This table describes the entire corpus of M&A activity for the population of the local exchange telecommunications companies including change in ownership, merger, or acquisitions

Company names Status 1988 to 1995 Status 1996 to 2001

Illinois Bell Telephone Company† An original Ameritech company Became a part of SBC in 1999

Indiana Bell Telephone Company Inc.† An original Ameritech company Became a part of SBC in 1999

Michigan Bell Telephone Company† An original Ameritech company Became a part of SBC in 1999

The Ohio Bell Telephone Company† An original Ameritech company Became a part of SBC in 1999

Wisconsin Bell Inc.† An original Ameritech company Became a part of SBC in 1999

Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company† An original Bell Atlantic Company which

became Verizon in 2000

An original Bell Atlantic Company which became Verizon in 2000

Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company of Maryland†

An original Bell Atlantic Company which became Verizon in 2000

An original Bell Atlantic Company which became Verizon in 2000

Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company of

Virginia† An original Bell Atlantic Company whichbecame Verizon in 2000 An original Bell Atlantic Company whichbecame Verizon in 2000

Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company of West Virginia†

An original Bell Atlantic Company which became Verizon in 2000

An original Bell Atlantic Company which became Verizon in 2000

The Diamond State Telephone Company† An original Bell Atlantic Company which

became Verizon in 2000

An original Bell Atlantic Company which became Verizon in 2000

The Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania† An original Bell Atlantic Company which

became Verizon in 2000

An original Bell Atlantic Company which became Verizon in 2000

South Central Bell Telephone Company† Stayed independent with operations

amalgamated as Bell South in 1992

Stayed independent with operations amalgamated as Bell South in 1992 Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Company† Stayed independent with operations

amalgamated as Bell South in 1992

Stayed independent with operations amalgamated as Bell South in 1992 Bell South† Stayed independent with operations

amalgamated as Bell South in 1992

Stayed independent with operations amalgamated as Bell South in 1992 New Jersey Bell Telephone Company† An original Bell Atlantic Company which

became Verizon in 2000

An original Bell Atlantic Company which became Verizon in 2000

New England Telephone & Telegraph Company† An original NYNEX Company An original NYNEX Company which became a

Bell Atlantic Company in 1997 which became Verizon in 2000

New York Telephone† An original NYNEX Company An original NYNEX Company which became a

Bell Atlantic Company in 1997, which became Verizon in 2000

Nevada Bell† An original Pacific Telesis Company Became a part of SBC in 1997

Pacific Bell† An original Pacific Telesis Company Became a part of SBC in 1997

Southwestern Bell Telephone Company† Stayed independent Stayed independent

The Mountain States Telephone and Telegraph Company†

Stayed independent till 1990 and operations amalgamated as US West Communications since 1991

Became a part of Qwest in 2000

Northwestern Bell Telephone Company† Stayed independent till 1990 and operations

amalgamated as US West Communications since 1991

Became a part of Qwest in 2000

Pacific Northwest Bell Telephone Company† Stayed independent till 1990 and operations

amalgamated as US West Communications since 1991

Became a part of Qwest in 2000

US West Communications, Inc.† Combined operations of Mountain States

Telephone and Telegraph Company, Northwestern Bell Telephone Company and Pacific Northwest Bell Telephone Company from 1991

Became a part of Qwest in 2000

Cincinnati Bell Telephone Company† Stayed independent Stayed independent

The Southern New England Telephone Company†

Stayed independent Became a part of SBC in 1998

Central Telephone Company of Virginia† Became a part of Sprint in 1992 Stayed as a part of Sprint

Contel of New York† Became a part of GTE in 1990 Stayed as part of GTE which then became part

of Verizon in 2000 Citizens Telecommunications Company Of New

York Inc.

Stayed independent Stayed independent

Contel of Texas† Became a part of GTE in 1990 Stayed as part of GTE which then became part

of Verizon in 2000

Contel of Virginia† Became a part of GTE in 1990 Stayed as part of GTE which then became part

of Verizon in 2000

Contel of California Inc.† Became a part of GTE in 1990 Stayed as part of GTE which then became part

acquired by Bell Atlantic. Bell Atlantic had also acquired NYNEX, an RHC in its own right, in 1997. The large Bell Atlantic eventually renamed itself Verizon. The motive was to bring together complementary assets and strengths, create scale and scope economies, permit innovations, and accelerate delivery of advanced services. Additionally, a motive

was to tackle competition from cable giants such as AT&T.

Several ILECs went through two merger transactions. The Continental ILECS went

through two merger transactions. First, they were acquired by GTE.Then, GTE became

part of Bell Atlantic.Similarly, the ILECs of GTE and NYNEX went through two merger

transactions. The first was when they were acquired by Bell Atlantic. The second was

when Bell Atlantic acquired Puerto Rico Telephone Company and then reconsolidated and renamed the whole group, consisting of erstwhile Bell Atlantic, Contel, GTE, NYNEX, and Puerto Rico Telephone Company, as Verizon. Pacific Telesis was first absorbed into SBC. Then Ameritech was absorbed into SBC, and the entire SBC structure recast. The series of second merger transactions took place after 1996. They led to the creation of giant firms within the sector. Any operating company belonging to these giants would be a formidable competitor in its territory.

Stated Merger Motives

The primary merger motivation was performance enhancement, to be lean so as to meet emerging competitive threats and improve performance. The companies stated that

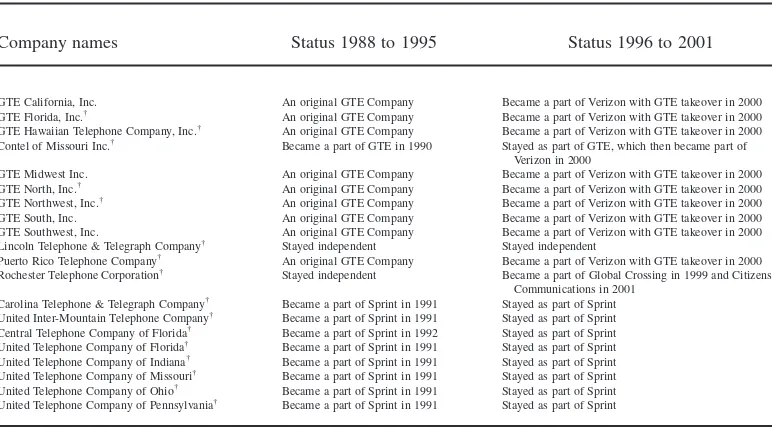

Table 1

Continued

This table describes the entire corpus of M&A activity for the population of the local exchange telecommunications companies including change in ownership, merger, or acquisitions

Company names Status 1988 to 1995 Status 1996 to 2001

GTE California, Inc. An original GTE Company Became a part of Verizon with GTE takeover in 2000 GTE Florida, Inc.† An original GTE Company Became a part of Verizon with GTE takeover in 2000

GTE Hawaiian Telephone Company, Inc.† An original GTE Company Became a part of Verizon with GTE takeover in 2000

Contel of Missouri Inc.† Became a part of GTE in 1990 Stayed as part of GTE, which then became part of

Verizon in 2000

GTE Midwest Inc. An original GTE Company Became a part of Verizon with GTE takeover in 2000 GTE North, Inc.† An original GTE Company Became a part of Verizon with GTE takeover in 2000

GTE Northwest, Inc.† An original GTE Company Became a part of Verizon with GTE takeover in 2000

GTE South, Inc. An original GTE Company Became a part of Verizon with GTE takeover in 2000 GTE Southwest, Inc. An original GTE Company Became a part of Verizon with GTE takeover in 2000 Lincoln Telephone & Telegraph Company† Stayed independent Stayed independent

Puerto Rico Telephone Company† An original GTE Company Became a part of Verizon with GTE takeover in 2000

Rochester Telephone Corporation† Stayed independent Became a part of Global Crossing in 1999 and Citizens

Communications in 2001 Carolina Telephone & Telegraph Company† Became a part of Sprint in 1991 Stayed as part of Sprint

United Inter-Mountain Telephone Company† Became a part of Sprint in 1991 Stayed as part of Sprint

Central Telephone Company of Florida† Became a part of Sprint in 1992 Stayed as part of Sprint

United Telephone Company of Florida† Became a part of Sprint in 1991 Stayed as part of Sprint

United Telephone Company of Indiana† Became a part of Sprint in 1991 Stayed as part of Sprint

United Telephone Company of Missouri† Became a part of Sprint in 1991 Stayed as part of Sprint

United Telephone Company of Ohio† Became a part of Sprint in 1991 Stayed as part of Sprint

United Telephone Company of Pennsylvania† Became a part of Sprint in 1991 Stayed as part of Sprint

the mergers would play a key role in the reconfiguration of operations and organizational infrastructures. Thereby, their performance would improve. In line with the importance given to synergy, the exploiting of complementary assets and skills, such as brands, human capital, and customer relationships, provided a motivation for mergers.

Allied to the notion of synergies was the ability for merged firms to combine resources to expand quickly, subject to regulatory approval, say, under Section 271 of the Telecom-munications Act of 1996, and to offer a bundle of products and services to an enhanced customer base. In the SBC and Pacific Telesis merger, bundling of local access and long-distance services could be feasible subject to Section 271 approval. The combined SBC and Pacific Telesis entity could offer this service, and make efficiency gains, as a result, through higher scale and volumes in respective territories (Goldman et al., 2003). The separate skills needed in providing local and intra-LATA long distance services could be jointly exploited across different territories, to which the firms were restricted, as these would now belong in a common pool of resources in the combined firm. The additional

service volumes would permit cost amortization and enhance efficiencies.13

Likely Merger Impact and Entry Hypothesis

What impact would the mergers have on new firm entry in the specific territories where they occurred? A sector operating characteristic is network effects. These are external economies, as described by Marshall (1890). They have been defined as network externalities and the presence of increasing returns to scale (Besen & Farrell, 1994; Liebowitz & Margolis, 2002). In a network context, ILECs and entrants could benefit from entry due to the additional demand generated by network externalities (Rohlfs, 2005; Shy, 2001).

The opposite can also be true. Network effects are an entry barrier (Werden, 2001). An ILEC, with anti-competitive ideas, by having access to better organizational infra-structure, through approved mergers, would be able to undertake targeted degradation of newly installed competitors’ facilities (Crémer, Rey, & Tirole, 2000). Such possibilities would induce less entry in the face of mergers in contexts where network effects prevailed. The risks of failure would be magnified, creating large sunk costs, via irreversible invest-ments, and the uncertainties of cooperative behavior from ILECs would heighten the risks involved in entry.14

13. By merging existing cable and telephone facilities, the merged entity could offer a combination of local phone, Internet, long distance, and broadband services far quicker than either of the firms on their own. In the US West and Qwest merger, the combining of US West’s expertise in providing xDSL to the local loop with Qwest’s high-speed, high-capacity network could lead to faster deployment of advanced services and to a larger customer base than US West could have deployed alone, thus strengthening the merged entity’s finances. The benefits of the mergers were likely on the customer base, which could be scaled up, and on research, service, and product development efforts. In the Bell Atlantic and GTE merger, greater scale and advertising possibilities would allow the merged entity to achieve efficiencies needed to develop a national brand. Further, the acquisition of GTE’s customers would provide Bell Atlantic with access to customers outside its territory (Goldman et al., 2003).

In the sector, a considerable amount of infrastructure investment took place by the ILECs in the period (Koski & Majumdar, 2002; Loomis & Swann, 2005). Most of the entrants were facilities-based new infrastructure entrepreneurs, incurring large sunk costs. Therefore, in the presence of incumbents’ mergers, entries of such entrepreneurs would reduce in the territories where these mergers occurred. The hypothesis tested in the analysis is of a negative relationship between incumbent ILECs’ mergers and the entry of new firms in each ILEC’s territory.

Details of Analysis

Method of Evaluation and Data

Longitudinal evaluation has been carried out to assess the dynamic impact of actual ILECs’ mergers on new firm entry in ILECs’ territories. The unit of analysis is the ILEC. A balanced panel of data for the 41 key ILECs, obtained from the Statistics of Commu-nications Common Carriers (SCCC) for the 14-year period of 1988 to 2001, has been used to conduct the panel data analysis. These data were based on a compilation of firm level operational and financial statistics, for all principal ILECs, for all the years between 1988 and 2001.

For decades, to support regulatory tasks, the FCC has been collecting detailed data on ILECs’ operations in a common format, standardized across all of the regulated firms. Numerous variables can be constructed from such information. Other data sources have been used. These have been the Federal-State Joint Board Monitoring Reports, FCC reports on Competition in the Telecommunications Industry, and National Regulatory Research Institute (NRRI) reports. These data have been used numerous times (e.g., Majumdar, 2011; Majumdar, Moussawi, & Yaylacicegi, 2010) before.

Effectively, the firms evaluated have formed the ILECs’ population. The total firm– year observations in the panel have been 574. For every firm after merger, its performance relative to itself in the past, when it had not been taken over, or relative to other firms in the same period, which had been either not taken over or taken over, can be evaluated in the data panel.

Entry Measure Dependent Variable

The primary dependent variable evaluated is CLECs’ entry. The entry of entrepreneur-ial competitors increased after the introduction of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. The competition data have been collected from the FCC Competition in Telecommunications

Industry reports. The variable has measured entry of new entrepreneurial firms (

Competi-tion). It has been calculated as a count variable, and is the number of licensed new

entrepreneurial CLECs present in each ILEC’s territory in each time period. Typically, each ILEC’s mandated territory is the state. There are some ILECs with multistate mandates. This variable represents the intensity of market competition in each state.15For a multistate

ILEC, the variable has been an average of CLECs across the number of territories

each ILEC operated in.16

Such a count measure, of new entrepreneurial firm entry, captures emergent competitive dynamics. The count measure has been used often in the competitive dynamics, entrepreneurship, industrial organization, and population ecology literatures (Brown & Zimmerman, 2004; Carroll & Hannan, 2000; Frech, 2002; Geroski, 1995;

Majumdar, 2011). Since a count measure has been used, it is not possible to identify17

the specific type of competitor as either a reseller, a lessee of unbundled lines, or as a facility-based entrant. Because, however, a considerable amount of infrastructure invest-ment took place by the ILECs in the period (Koski & Majumdar, 2002), most of

the entrants have been facilities-based new infrastructure investors.18

Since, however, the analysis of the article deals with a specific phenomenon of mergers and entry at a particular time and context, the geographic specificities for that context have been taken into account.

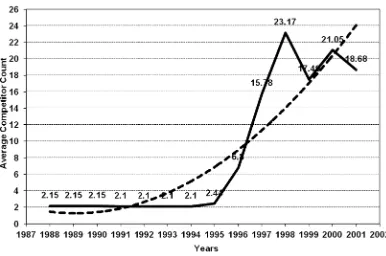

Figure 1 displays the average values for the Competition variable, computed as an

average of the variable for all firms in all territories, over each period of time. Between 1996 and 2001, there was a tapering off of this growth, possibly as the result of the decline of several CLECs’ businesses, as well as industry meltdown. This tapering off could be due to the aggressive anticompetitive behavior of the ILECs (Ferguson, 2004; Koski & Majumdar, 2002) protecting their monopolies. The average number of new entrepreneur-ial firms, present within each territory, in the 1996 to 2001 period was more than four times the average number of such firms, present within each territory, in the 1988 to 1995 time span. Clearly, a major structural change occurred in the sector.

Merger Variables

A dummy variable denotes the occurrence of a merger, and once an ILEC has engaged in a merger act it is thereafter identified as a merged entity for later periods. All the merger acts fully corresponded with a list of mergers maintained at

Conversely, the number of entrants served to enhance the number of possible competitors each ILEC would face, even after a merger.

16. The industry has moved, in the past 15 years, from being a set of local, regulated monopoly firms, with a clear geographic specificity, to a set of geographically diffuse national competitive firms, especially with the emergence of wireless and Internet communications. The data set covers a period when the local, specific competitive landscape was as demarcated in detail as it could be, and the matching of competitors was as relevant as feasible, though with the advent of CLECs, from the mid-1990s, competition began to become geographically diffuse and generalized. Now, of course, two or three wireless companies provide diffuse, generalized competition for other communications providers in the industry.

17. Path dependencies matter in entrepreneurial behavior; however, entrants’ identities were not available. It was not feasible to identify whether past entry in one territory by a specific competitor might lead it to enter other territories at the same time or at later period.

http://www.cybertelecom.org. Several merger transactions have been studied. The design of dummy variables to control for merger impact is based on prior research on mergers (Gugler & Yurtoglu, 2004; Majumdar et al., 2010). Given the sector’s circumstances, two merger variables have been used: a merger dummy if an ILEC went through a merger transaction once; and a second merger dummy variable in case an ILEC expe-rienced a merger transaction a second time. For example, Pacific Bell and Nevada Bell, part of Pacific Telesis, initially merged with Southwestern Bell, the ILEC of SBC. A few years later, SBC acquired Ameritech; then, the entire ILEC operations, including that of Pacific Bell and Nevada Bell, were consolidated within SBC. Thus, Pacific Bell and Nevada Bell went through two merger transactions.

The way the firms keep records, based on regulatory accounting maintained require-ments to this day, each ILEC has retained its accounting identity set up decades ago. Even if an ILEC has been taken over, by merger, this accounting identity has remained. The data reported for the period 1988 to 2001 are based on these identities. This feature is useful, because it permits clean analysis for a panel consisting of a large cross-section, per period, as well as a long time series. In the cross-section, for any year, the behavior of a non-merged ILEC can be compared with that of a merged ILEC. In the data time series for a particular ILEC, its behavior as a merged firm can be compared relative to its behavior when it was a non-merged ILEC. If the merger variable is used as an explanatory variable, then, within a panel, whether an ILEC has merged or not is clearly

Figure 1

identifiable in each time period, and the impact of such a contingency on the dependent variable evaluated.19

Dynamic merger analysis has been necessary. Concerns relate to the motivations of entrants, speed of adjustment, interrelationships between the strategic decisions of incumbents to merge and for competitors to enter a market. These concerns can be addressed by introducing merger dummy variables with time lags. To differentiate between immediate and longer mergers’ effects on entrants’ behavior, a time-variant post-merger dummies design (Elsas, 2004; Majumdar et al., 2010) has been used. This research design for merger impact analysis isolates the impact of each time period before mergers as well as that of the contemporaneous period on entry patterns. For the first and second mergers, dummy variables have been constructed for two periods pre-ceding the merger, for the merger period, and for a period after the merger. A period has been a year.

The explanatory variables have beenfirst mergert-2, first mergert-1,first mergert0, and

first mergert+1. Similarly, other variables are second mergert-2, second mergert-1, second

mergert0, andsecond mergert+1. A 4-year evaluation of merger transactions is feasible with

such a design. A two-prior-period design picks up potential new entrepreneurial entrants’ actions from time of announcement to time of consummation. Generally, most merger announcements and consummation take place in a year. In this sector, often 2 or more years have elapsed between announcement and consummation because of the need for regulatory clearances to be obtained. Thus, dummies before the merger transactions evaluate new firm entry in the periods preceding the merger consummation; merger dummies for the merger year evaluate the impact of mergers on entry during the consum-mation year itself; and, merger dummies for the post-merger period evaluate the entry impact of consummated mergers a year later.

Control for the Telecommunications Act of 1996

Comprehensive entry evaluation would necessitate taking into account the influence of many factors (Geroski, 1995). The importance of institutional factors has been high-lighted in the early part of the article. An important such institutional factor in the sector was the passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (Act of 1996). The impact of this legislation would be important in inducing entry in ILECs’ markets, as this industry structure-changing legislation was intended to bring in competition into the sector monopolized by the ILECs. To control for the change in industry structure after 1996, a dummy control variable was introduced.

Control for Section 271 Effects

So that they could enter into other inter-LATA long distance markets, the 1996 legislation required ILECs to meet requirements under Section 271 of the Telecommuni-cations Act of 1996 (Economides, 1999). Prior work (Brown & Zimmerman, 2004) had found the Section 271 rules as influencing entry positively in jurisdictions where permis-sion had been granted. Based on the data on Section 271 approvals, as given in Brown and

Zimmerman, a dummy variable was added for the observations where such approval had been given.

Intermodal Competition

An additional competitive factor controlled for dealt with intermodal competition from cable companies (Loomis & Swann, 2005). These possibilities could intensify competition in local exchange markets, and make these markets unattractive for her new entrants. The erstwhile AT&T, the long-distance company, had purchased several cable companies, such as TCI, Media One, and Lenfest in 1999. It also purchased the down-town Boston assets of Cable Vision. All these cost well over $100 billion, and the AT&T cable business could provide substantial competition to incumbents and new

entrants. A dummy variable (AT&T Cable), coded as 1 for the years that AT&T owned

its cable assets and 0 otherwise, was included to account for the AT&T intermodal competitive threats.

Residual Environmental Effects

The effect of mergers on entry could be confounded by other factors occurring simultaneously within the sector, such as the diffusion of wireless services, and other exogenous economic circumstances, such as macroeconomic events. To evaluate whether or not the mergers had an impact exclusive of such time-related factors on entry, a time

index variable(time index)was added in the regressions.

Price Regulation Effects

A variable controlled for the impact of price regulation on entry in the local exchange sector (Abel, 2002; Majumdar et al., 2010). Over the period evaluated, there were major transitions in regulatory regimes, principally a movement away from rate of return regulation. These changes were expected to be major (Sappington, 2002). Rate of return regimes could be entry deterring, as firms engaged in cost-pass-through, making entrants’ business models uncompetitive.

Data on state-specific regulatory regime changes in the United States telecommuni-cations industry have been collated and maintained by David Sappington (Sappington, 2002) and Dennis Weisman (Weisman, 1993). The latest full set of data was made available by their generosity. For all of the firms, if the regulatory regime was based on

rate of return principles(rate of return regulation)it was coded as such for each period

relative to other regulatory regimes in operation.

For firms that operated in multiple state jurisdictions that might vary in regulatory regimes, a weighted average value for the regulatory regime was computed for each operating company observation by weighting the regulation observation by the proportion of lines that each state contributed to the total access lines operated by the company. This approach was consistent with the literature (Brown & Zimmerman, 2004; Majumdar, 1997, 2011; Sappington, 2002).

Technology Effects

A measure used to capture technology deployment by the ILECs was the ratio of the total

investment in broadband. Resources within an ILEC, investing higher amounts in broadband, could signal formidable abilities and scare off potential entrants from that territory.20

Additional Controls

Additional controls were required. See Majumdar (2011) for extensive details. A factor

affecting demand was the extent of business lines. The business lines construct(business)

was the ratio of total business lines to total access lines for each firm. Larger business line shares could encourage entry. Similarly, a higher urban population ratio in a territory

could attract entry. The urban population ratio(urban)was the weighted average ratio of

urban population to total population in each firm’s territory. This ratio was weighted by the fraction of lines that the firm had the operating rights to in specific states. These factors might have had an opposite effect, though; in business-rich and urban locations, a strong ILEC could provide robust competition and scare new entrepreneurial entrants off.

The use of market share constructs was a proxy for ILECs’ market position. A firm with a stronger market position could exercise power for entry deterrence. The market

position variable (market position) was constructed by taking the ratio of a firm’s total

number of lines across the states it operated to the total number of lines in all states it operated in. The use of the market share construct was a proxy for the possible market or regulatory power of the local exchange carriers. In regulated industries, a high market share does not imply monopoly behavior. Yet, inclusion of the markets a firm was involved with, in market share calculations, provided a sense of the relative presence of that firm in its territory.

Entry was found to be positively related to industry performance and growth (Sieg-fried & Evans, 1994). Two controls, taking into account these possibilities, were ILECs’

past financial performance(performance),calculated as the ratio of total revenues to total

operating assets, and a revenue growth (growth) variable. Incumbents’ size could

influ-ence entry; a size variable (size)was included. The log of total operating revenues was

the size measure. Similarly, a higher customer expenses ratio could attract entry as the

incumbent had developed the market. The ratio used(customer)was the ratio of customer

expenditures to total revenues for each incumbent firm.

Control for Past Entry

Finally, a control was included for past entry, to control for possible firm-specific effects of the different entrants as well as territory-specific effects on entry. A particular territory that had experienced above average entry in the past might experience similar contemporaneous entry. For each observation, a variable was constructed as the ratio of past period entry to average entry in the industry as a whole for that earlier period (prior entry). This variable, as constructed, controlled for territory-specific drivers of entry other than merger effects.

Appendix 1 contains a correlation matrix for the different variables.

Results

Estimation

An appropriate dynamic estimation approach for the issue examined was the negative binomial distribution (NBD) model (Hausman, Hall, & Griliches, 1984). This is a special case of the Poisson regression model (Hausman et al.). (The results from the estimations for the full period of 1988 to 2001 are given in Table 3.) As alternative measures of new entrepreneurial firm entry were unavailable, use of the count measure required that an appropriate estimation technique dealing with such models (Cameron & Trivedi, 1998), such as the NBD approach, be used.

Results

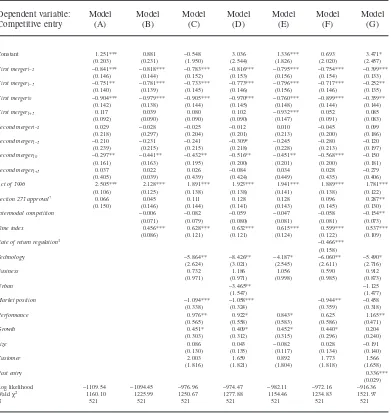

In Table 2, the results from seven specifications of the NBD model are given. These are for the full panel data set for 1988 to 2001. These specifications were estimated so as to test the stability of the merger estimates to the introduction of the various time-related institutional and other control variables which could directly affect competitive entry.

Models (A) to (E) are discussed first. Model (A) just included the merger variables, theAct

of 1996 and the Section 271 Approval variable. Model (B) included, additionally, the intermodal competition, and thetime indexvariables, while model (C) included additional

control variables, such as thetechnology, business, market position, performance, growth,

size, andcustomervariables. Model (D) additionally included theurbanvariable. Model

(E) excluded themarket positionand theurbanvariables.

In each of these five specifications, for the first merger, the prior and contemporaneous

merger variables were found to be negative and significant, all atp-values of<0.01. The

post-merger entry variable was insignificant in Models (A) to (D) but was negative and significant in Model (E). With respect to the second merger variables, the prior period and post-merger variables were insignificant, but the contemporaneous variable was negative and significant (p-value<0.01). An issue to be considered was the relative strength of each

local market carrier in its jurisdiction. A large market position might dampen entry, and the effect of mergers on entry. The presence of a large urban market may have led incumbents to become strong, and this may have deterred entry. To evaluate these contingencies, the market position and urban variables were dropped in the Model (E) specification. All merger variables stayed as noted with the addition that the post-merger variable for the first merger was negative and highly significant. Its estimate size was also substantial.

Models (F) and (G) included all variables including therate of return regulationand

past entryvariables, while excluding others. The merger results reverted to those noted for models (A) to (D). A variety of specifications has thus established the stability of the merger coefficients. These stayed remarkably consistent across the models. They did not change in size, sign, or significance. In the relevant specifications, the results were

established after controlling for the fundamental impact of theTelecommunications Act of

1996which would promote entry autonomously as intended. TheAct of 1996variable was

positive and significant in the various models. The passage of the legislation had promoted

entry. TheSection 271 Approvalvariable was not significant, except in model (G), and the

rate of returnregulation variable was negative and significant atp<0.01 in model (F).

Additional Estimation

particular territory at each particular time, relative to the average entry in the industry as a whole for that particular time. This measured above average or below average entry. The key issue to be evaluated would be whether merger approvals and consummations led to above or below average levels of entry. The standard panel data technique was used for this analysis, and estimations were carried out using fixed effects, random effects, and maximum likelihood approaches. The results were identical in each approach, and only the maximum likelihood estimates are reported in Table 3.

Table 2

Results of the Panel Fixed Effects NBD Regression Analysis

Dependent variable:

Constant 1.251*** 0.881 -0.548 3.036 1.336*** 0.693 3.471*

(0.203) (0.231) (1.950) (2.544) (1.826) (2.020) (2.457)

First mergert-2 -0.841*** -0.818*** -0.783*** -0.816*** -0.795*** -0.754*** -0.399***

(0.146) (0.144) (0.152) (0.153) (0.156) (0.154) (0.133)

First mergert-1 -0.751** -0.781*** -0.733*** -0.773*** -0.796*** -0.717*** -0.252**

(0.140) (0.139) (0.145) (0.146) (0.156) (0.146) (0.135)

First mergert0 -0.904*** -0.979*** -0.905*** -0.970*** -0.760*** -0.899*** -0.359**

(0.142) (0.138) (0.144) (0.145) (0.148) (0.144) (0.144)

First mergert+1 0.117 0.039 0.080 0.102 -0.932*** 0.052 0.085

(0.092) (0.090) (0.090) (0.090) (0.147) (0.091) (0.083)

Second mergert-2 0.029 -0.028 -0.025 -0.012 0.010 -0.045 0.099

(0.218) (0.297) (0.204) (0.201) (0.213) (0.200) (0.186)

Second mergert-1 -0.210 -0.231 -0.241 -0.309* -0.245 -0.280 -0.120

(0.239) (0.215) (0.215) (0.218) (0.228) (0.213) (0.197)

Second mergert0 -0.297** -0.441** -0.432** -0.516** -0.451** -0.568*** -0.150

(0.161) (0.163) (0.195) (0.200) (0.201) (0.200) (0.181)

Second mergert+1 0.037 0.022 0.026 -0.084 0.034 0.028 -0.279

(0.405) (0.039) (0.439) (0.424) (0.449) (0.435) (0.406)

Act of 1996 2.505*** 2.128*** 1.891*** 1.923*** 1.941*** 1.889*** 1.781***

(0.106) (0.125) (0.138) (0.138) (0.141) (0.138) (0.122)

Section 271 approval† 0.066 0.045 0.111 0.128 0.128 0.096 0.287**

(0.150) (0.146) (0.144) (0.141) (0.143) (0.145) (0.130)

Intermodal competition -0.006 -0.082 -0.059 -0.047 -0.058 -0.154** (0.071) (0.079) (0.080) (0.081) (0.081) (0.073)

Time index 0.456*** 0.628*** 0.632*** 0.615*** 0.599*** 0.537*** (0.086) (0.121) (0.121) (0.124) (0.122) (0.109)

Rate of return regulation‡

-0.466*** (0.158)

Technology -5.864** -8.426** -4.187* -6.060** -5.490* (2.624) (3.021) (2.545) (2.611) (2.716)

Business 0.732 1.186 1.056 0.590 0.912 (0.971) (0.971) (0.998) (0.985) (0.873)

Urban -3.465** -1.125

(1.547) (1.477)

Market position -1.094*** -1.058*** -0.944** -0.458

(0.338) (0.324) (0.359) (0.318)

Performance 0.976** 0.922* 0.843* 0.625 1.165** (0.565) (0.558) (0.583) (0.586) (0.471)

Growth 0.451* 0.409* 0.452* 0.440* 0.204 (0.303) (0.312) (0.315) (0.296) (0.240)

Size 0.086 0.043 -0.082 0.028 -0.191

(0.130) (0.135) (0.117) (0.134) (0.140)

Customer 2.003 1.659 0.892 1.773 1.566 (1.816) (1.821) (1.804) (1.818) (1.658)

Past entry 0.336***

(0.029) Log likelihood -1109.54 -1094.45 -976.96 -974.47 -982.11 -972.16 -916.36

Waldc2 1160.10 1225.99 1250.67 1277.88 1154.46 1234.83 1521.97

N 521 521 521 521 521 521 521

Standard errors in parentheses. *p<0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01

†Section 271data based on Brown and Zimmerman (2004).

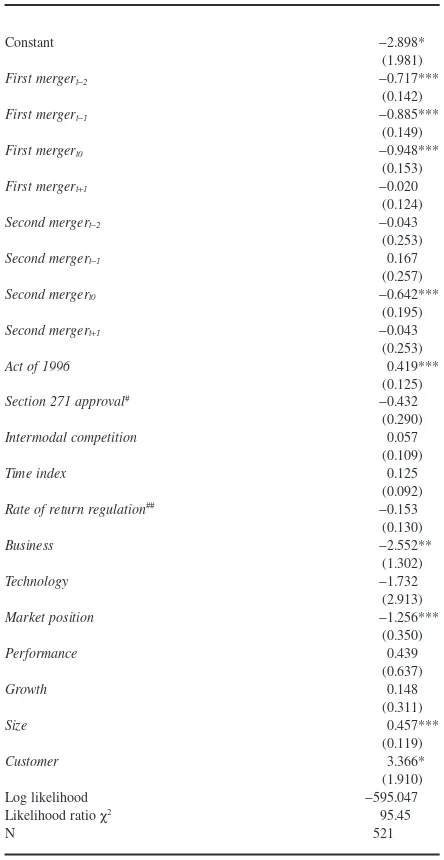

Table 3

Results of the Regression Analysis With Alternative Dependent Variable and Using Maximum Likelihood Specifications

Dependent variable: Ratio of competitive entry relative to industry entry

Second mergert-1 0.167

(0.257)

#Section 271data based on Brown and Zimmerman (2004).

##Rate of return regulation data provided by David Sappington and

In the new five specification of the dependent variable, the prior and contemporaneous

first merger variables were negative and significant, all at p-values of < 0.001. The

post-merger coefficient for the first merger was insignificant. With respect to the second merger variables, the prior period and post-merger variables were insignificant, but the

contemporaneous variable was negative and significant (p-value<0.001). These results

mimic the previous results presented; they signify that the merger process in the industry did deter new firms from entry. Levels of entry were below average, relative to the levels of entry in the industry as a whole, in territories where mergers had occurred.

Broad Findings

Had the mergers, as approved and consummated, promoted new firm entry? The basic premise behind merger approvals had been that mergers would promote entry, not deter it. Hence, merger approvals were not to be held back by authorities. Based on this premise, very few merger approvals were held back, as it was assumed that merging firms’ anticompetitive behavior would be dealt with via emergent competitive market dynamics. In the analysis for the telecommunications sector, the variables in respect of first mergers, for prior periods, the contemporaneous period and for the post-merger periods, were negative and significant or insignificant. Hence, the probability of a merger taking place, based on prior announcements made, which the lagged values will have measured, motivated CLECs to not enter the territories where incumbent firms announced merger intentions. The actual taking place of a merger, in a particular territory, had a significantly negative impact on new entrepreneurial firm entry by the CLECs. In the period after a merger deal had been consummated, no significant new entrepreneurial firm entry took place. Possibly, the CLECs were significantly scared off.

The second merger variables, both prior period and contemporaneous, were negative but the contemporaneous value alone was significant across specifications. The post-merger variable was insignificant. These second post-mergers all took place in the late 1990s and early 2000s. By this time, the contours of the emerging post-mergers market place were known to CLEC entrants. Hence, the probability of a merger taking place, based on announcements, which the lagged values will have captured, again motivated the new entrepreneurial competitive firms to not enter. The actual taking place of second mergers, in particular territories, had a significantly negative impact on entry.

Interpretation

The key contributions of the analysis have been in highlighting how mergers influ-enced telecommunications sector new firm entry. The implications of the findings deserve some analysis. The interpretations of the coefficient estimates highlight important trends in new entrepreneurial entrants’ behavior. The coefficient for each periodic merger vari-able was the entry, or otherwise, of competitors during the period of either the merger being planned or announced, as the prior period merger variables denoted; the entry during the period of the merger taking place, as given by the contemporaneous merger variable; and the entry during the first period after the merger had been consummated.

The following interpretations have been based on the estimates from the results in model (F) in Table 2. Each coefficient estimate represents the number of entrants that have either entered, a positive sign, or declined to enter, a negative sign, in each merger event

period. This period could be one of announcement, say,first mergert-1, or of

For a first merger event, its occurrence led to almost 14% relatively lower entry in territories where mergers had occurred. This was decomposed as: almost 9% lower entry in two periods prior to the merger, being over 4.5% lower entry in the announcement period 2 years prior to merger consummation, and over 4% lower entry in the period preceding merger consummation. There was 5% lower entry in the merger period itself. In the post-merger period, there was hardly any new entrepreneurial firm entry at all.

For a second merger transaction, the impact of such a transaction led to 5% relatively lower new entrepreneurial firm entry. This was decomposed as: cumulative 2% lower new entrepreneurial firm entry in the two periods prior to the merger consummation and 3% lower entrepreneurial firm entry in the merger consummation period itself. In the post-merger period, there was insignificant new entrepreneurial firm entry. Cumulatively, in the sector the first and second mergers led to 19% lower entry.

In relative percentage terms, the magnitude of lowering of entry may have seemed small. The actual number of firms that did not enter, or exited, might be in single digits. In an oligopolistic sector such as local exchange telecommunications, where the number of entrants would have been small, because of the very large sums of money required to invest in infrastructure and facilities, the disappearance of even one or two players from the field would have important consequences in terms of limiting incumbents’ potential anticompetitive behavior, and offering customers diversities in choices. Thin markets experienced today, in terms of few choices open to customers that want new cable or wireless connections, denote the importance of entry in the communications sector. More suppliers are always better toward enhancing customer choices, lowering prices, and engendering welfare.

Conceptual Implications

Where mergers did occur, significantly lower new firm entry was noted. What is the conceptual implication of this finding? In most other sectors, this reduction in new entrepreneurial firm entry would be in keeping with the observation about the small scale, de-novonature of new entrepreneurial firm entry, and the short life expectancies of such entrants (Geroski, 1995). Conversely, the new entrepreneurial CLECs concentrated their efforts on network building so as to provide infrastructure-based competition (Woroch, 2002). The new entrepreneurial CLECs could have been effective competitors, since they were involved in making network investments characterized by large sunk costs. Hence, the new entrepreneurial sector entrants were not just markets participants, wanting to enjoy lucrative new revenue streams, but were committed entrants, investing for the long run, as defined by the 1992 Merger Guidelines.

The results show that merger approvals and consummation deterred entry in the telecommunications sector. Why would entrants have behaved in this way? After all, the conceptual dominant logic at work would have us believe mergers would trigger entry, thereby establishing the primacy of evolving competitive market dynamics as a disciplin-ary device for future anticompetitive behavior. Since the entrants were actually new entrepreneurial facility-based CLECs, in the main, the possible compromise of the large capital sums required would have magnified entry risks.

since these CLECs were unused to operating in the regulated communications sector. These differences would have influenced their risk perceptions.

The presence of sunk costs and uncertainty, as ancillary barriers to entry, would create structural sector risk. Entry requiring large sunk costs could enhance post-entry risk of large losses. Incumbents’ merger approvals would magnify such risks for entrants, because the ILECs would acquire control over a larger resource base, as a result of which there was a deterrent effect of the incumbents’ mergers. This would have caused CLEC firms to avoid entry in the face of mergers. Additionally, the new entrants were second movers in a sector of industry in which the incumbents were old established players with considerable history. Other barriers, say political ones, could have been created by the merging incumbent firms to thwart the business models of these new entrants.

In fact, the literature records evidence of anticompetitive behavior by the incumbents (Ferguson, 2004; Koski & Majumdar, 2002), especially after the passage of the Telecom-munications Act of 1996. Other related work on incumbents’ mergers (Majumdar et al., 2010) established that the merged ILECs did not engage in behavior that was in their employees’ best interests. Consequently, the new entrants may have foreseen emergent barriers to business expansion. As ILECs obtained greater resources via mergers, they would retain supreme power in their territories, and could have implemented numerous market-domination strategies against the entrants. This would make business difficult, and make the entrants fight “uphill battles” for survival. The anticipation of these prospects would have acted as major entry deterrents.

An important issue was that ILECs were viewed as potential entrants outside their own territories. They could become CLECs elsewhere. The remedies for mergers by incumbent local exchange carriers included promises to enter other local markets. The possibilities that large ILECs might enter other ILECs’ territories, where mergers had occurred, could have acted as a deterrent against entry. Two incumbents operating in a given territory would exacerbate competitive pressures; they could create disadvantages

for other smaller entrants that would then find viability infeasible. TheTwomblycase, filed

against Bell Atlantic and others, alleged “failure to enter” as a conspiracy by incumbents to not enter each other’s markets and enhance competition. By not doing so, the ILECs could retain the strength to tackle other entrants in their own territories.

As competitors, the ILECs as entrants would face reprisals from incumbents who would find their own lucrative businesses being attacked by strong competitors. If the ILECs then also merged, they would have the resources to engage in stringent competitive actions which could sharply reduce new entrants’ asset values. With mergers enhancing the possibilities of entrants’ asset degradation, since ILECs could adopt strategies of competitive harm, less entry occurred in the territories where mergers had occurred.

Discussion

Given that considerable entrepreneurship research deals with issues of strategy as well as public policy, this article has made theoretical and empirical contributions across areas. By combining ideas from the literatures on antitrust, economics, entrepreneurship, and strategy, the article highlights how an important issue, that of mergers by incumbents, and their institutional approval, can affect entrepreneurial behavior.