Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:17

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Corporate-Academic Partnerships: Creating a

Win-Win in the Classroom

Dawn Reneé Deeter-Schmelz

To cite this article: Dawn Reneé Deeter-Schmelz (2015) Corporate-Academic Partnerships: Creating a Win-Win in the Classroom, Journal of Education for Business, 90:4, 192-198, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1014457

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1014457

Published online: 16 Mar 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 74

View related articles

Corporate-Academic Partnerships: Creating

a Win-Win in the Classroom

Dawn Rene

e Deeter-Schmelz

Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas, USA

For instructors seeking ways to provide sales students with experiential learning projects designed to develop and enhance skills in an authentic environment, corporate-academic partnerships offer a viable option. The author describes a unique and innovative corporate-academic integrated project, including course content, role plays, and corporate partner involvement, implemented in the sales management course. After reviewing the experiential learning literature and outlining the project, assessments of the project’s efficacy are conducted. Based on the quantitative and qualitative results reported, implications and considerations for the classroom are offered.

Keywords: corporate-academic partnership, experiential learning, integrated project, role plays, sales management

As a result of intensifying competition for both customers and resources, many organizations are turning to higher education for assistance (Todd & Ramachandran, 2007). In response, business academics increasingly are using peda-gogical tools and methods designed to develop workplace skills and capabilities (Bennis & O’Toole, 2005). Methods such as project-based (e.g., Danford, 2006; Walker & Leary, 2009) and experiential learning (e.g., Carver, 1996; Kolb, 1984) actively engage students to work on real world problems for corporations. If projects are designed appro-priately, students can make a valuable contribution to an organization while at the same time achieving educational objectives; as such, value is delivered to the students, the university, and the corporate partner (Laughton & Ottewill, 1998).

For students, the exposure to real-world business prob-lems results in an enhanced learning experience derived from applying theory to practice (Danford, 2006). Students can develop an understanding of what it means to be a busi-ness professional and leader (Allen, Wachter, Blum, & Gil-christ, 2009), and advance their interpersonal and communication skills (Laughton & Ottewill, 1998). Colla-bortion with businesses supports placement activities by providing students with networking and job opportunities (Danforth, 2006) and offering a preview of the

requirements and tasks associated with a given job role (Laughton & Ottewill, 1998).

In addition to reaping benefits for students, universities accrue value from such partnerships. These benefits can include building an enhanced image in the business com-munity (Danforth, 2006). By developing relationships with local businesses and providing research assistance, univer-sities can enhance town-gown relations and ease the way for fundraising efforts. Research opportunities might also arise as faculty develop relationships with firm members and identify opportunities for research collaboration (Daforth, 2006).

Finally, corporate-academic partnerships deliver great value to participating firms. Danforth (2006) highlighted sev-eral key benefits associated with such alliances including increased access to (a) faculty expertise and (b) cost-effective resources (i.e., students). First and perhaps most obviously, the corporate partner receives research and potential solutions on an important business problem at little to no cost. Second, students can develop the skills and competencies sought by the corporate partner. Firms get to know the students and their particular talents early in the students’ careers, and can deter-mine who may be a good fit for a particular role. Information about the corporate brand and values can be shared, thereby facilitating the hiring process and potentially reducing the costs associated with recruiting. All parties benefit.

The purpose of this article is to present a unique, innova-tive experiential learning project that arose from a

Correspondence should be sent to Dawn Renee Deeter-Schmelz, Kansas State University, Department of Marketing, 2C Calvin Hall, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA. E-mail: ddeeter@k-state.edu

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1014457

corporate-academic partnership and delivered value to all parties. This project was designed specifically to address the need for college graduates with appropriate skills. The following sections explore experiential learning as the foundation for corporate-academic integration. Next, a sales management project undertaken with a specific corpo-rate partner is described. The nature of the project is out-lined, the case and role plays developed for the project are described, and the integration of company representatives in the classroom is discussed. After a review of the study methodology, the investigation of potential changes in students’ perceptions is presented, along with qualitative data from students and corporate partner representatives. Finally, the findings of the study are discussed, with impli-cations for educators and corporate partners seeking to cre-ate similar experiences provided.

EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING PROJECT: THE SALES MANAGEMENT CLASS

The project, developed for a sales management class, was designed to provide students with real-world experience, further develop students’ selling skills, and develop students’ coaching skills. Students entering sales positions upon graduation will benefit from strong selling skills, as will the companies that hire them (cf. ManpowerGroup, 2013), and coaching skills are often lacking in sales manag-ers (Vazzana & Jordan, 2013).

To meet these goals, experiential learning was used as the foundation for project design. Kolb (1984) described experiential learning as a “process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (p. 38). Carver (1996) identified four pedagogical principles associ-ated with experiential learning: (a) authenticity, (b) active learning, (c) drawing on student experience (i.e., reflecting), and (d) providing a means for connecting the experience to future opportunity. Role playing has long been considered a method for delivering experiential education, in part because of the focus on developing communication and critical thinking skills within the confines of a real-world simulation (McBane & Knowles, 1994). As such, the deci-sion was made to incorporate role plays as a key component of the experiential learning project, following the pedagogi-cal principles outlined by Carver (1996).

The Case and Role Plays

Frito Lay served as the project corporate partner, with a Frito Lay manager writing a case to provide context for the role plays. This case was based on events normally experi-enced by front-line sales managers (known as district sales leaders [DSLs]), thereby enhancing project authenticity (Carver, 1996). Key roles in the case include Corey, a Frito Lay route sales representative (RSR), and Jim, a grocery store manager. Jim is complaining of service problems, and

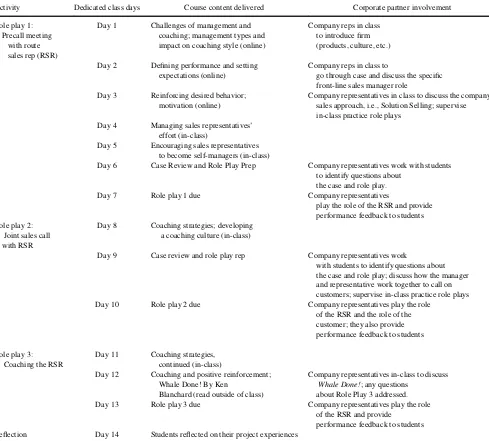

the store owner (Jim’s boss) has removed one of Frito Lay’s largest in-store displays located near the checkout, making it difficult for Jim to meet store plan and rebate goals. The student, playing the role of the DSL, is charged with coach-ing Corey through this situation and helpcoach-ing him develop a plan to improve Jim’s sales. The project timeline, course content, and corporate partner involvement can be seen in Table 1.

The first role play outlined a precall meeting between the DSL and RSR. The student had three assigned goals: (a) uncover the source of store complaints, (b) coach Corey on how to resolve those complaints, and (c) help Corey develop a plan to meet the customer’s sales goals. Students were provided with resources to assist in preparation, including promotion and display information; a heat map showing the most heavily shopped store locations; and store sales data. These same resources are used by DSLs daily, lending authenticity to the case (Carver, 1996).

In Role Play 2 the student DSL accompanied Corey to a meeting with Jim. The meeting’s purpose was to ensure that all complaints were resolved and propose the strategies devised in Role Play 1. This role play addressed the instructor’s desire to further develop selling skills, as well as collaboration and coaching skills, within a real-world simulation to promote active learning (Carver, 1996; Frontczak, 1998).

The final role play encompassed a coaching session with Corey to go over fourth-quarter results. A new twist was introduced: although Jim met plan goals due to the sales strategy implemented, other accounts managed by Corey did not fair as well. The student was charged with coaching Corey on how to improve performance next quarter. This role play promoted active learning and served to further develop students’ coaching skills.

Implementation of the Project

With the case and role plays developed, the integration of theories and concepts to the learning process were addressed (Young, 2002). Connecting the students’ experi-ences to their future careers was also considered (Carver, 1996). Students were supplied an adequate base of knowl-edge prior to completing the role plays (Table 1). To pro-vide sufficient background on coaching, the students read the book Managing Effort, Getting Results: A Coaching System for Managers (McHardy & Marshall, 2003). Con-tent was delivered via a combination of online voiced-over PowerPoint slides and in-class lectures. Students were also assigned the book Whale Done! The Power of Positive Relationships (Blanchard, Lacinak, Tompkins, & Ballard, 2002), used in the corporate partner’s training of managers. Of utmost importance was delineating core theories and concepts and subsequently linking them to the role plays (Carver, 1996; Kolb, 1984).

CORPORATE-ACADEMIC PARTNERSHIPS 193

The remaining class time was devoted to interacting with the corporate partner’s representatives. The company brought in a variety of personnel, each uniquely qualified to present a specific topic to students. A DSL visited the class to explain her day-to-day activities, her coaching strategies, and how students might implement this information in their role plays and future careers. To provide a broader under-standing of the company’s selling style, a company sales trainer visited the class. In short, the company immersed the students in the company products and culture. The instructor also integrated company examples with theoreti-cal concepts to enhance students’ understanding of how

these theories and concepts would be meaningful to their future careers.

After each role play students received extensive feed-back from the instructor and Frito Lay representatives. Some feedback was immediate, given by Frito Lay person-nel playing the roles of Corey or Jim. Additional Frito Lay employees, along with the instructor, watched the role plays on live feed and provided written constructive comments. Both the immediate and written feedback served to facili-tate the students’ reflective processes.

As a final step, students were asked to think about the project and identify two critical items learned and describe

TABLE 1

Project Timeline, Course Content, and Corporate Partner Involvement

Activity Dedicated class days Course content delivered Corporate partner involvement

Role play 1: Precall meeting

with route sales rep (RSR)

Day 1 Challenges of management and coaching; management types and impact on coaching style (online)

Company reps in class to introduce firm (products, culture, etc.)

Day 2 Defining performance and setting expectations (online)

Company reps in class to

go through case and discuss the specific front-line sales manager role

Day 3 Reinforcing desired behavior; motivation (online)

Company representatives in class to discuss the company’s sales approach, i.e., Solution Selling; supervise in-class practice role plays

Day 4 Managing sales representatives’ effort (in-class)

Day 5 Encouraging sales representatives to become self-managers (in-class)

Day 6 Case Review and Role Play Prep Company representatives work with students to identify questions about

the case and role play. Day 7 Role play 1 due Company representatives

play the role of the RSR and provide performance feedback to students Role play 2:

Joint sales call with RSR

Day 8 Coaching strategies; developing a coaching culture (in-class)

Day 9 Case review and role play rep Company representatives work

with students to identify questions about the case and role play; discuss how the manager and representative work together to call on customers; supervise in-class practice role plays Day 10 Role play 2 due Company representatives play the role

of the RSR and the role of the customer; they also provide performance feedback to students

Role play 3: Coaching the RSR

Day 11 Coaching strategies, continued (in-class)

Day 12 Coaching and positive reinforcement; Whale Done! By Ken

Blanchard (read outside of class)

Company representatives in-class to discuss

Whale Done!; any questions about Role Play 3 addressed. Day 13 Role play 3 due Company representatives play the role

of the RSR and provide performance feedback to students Reflection Day 14 Students reflected on their project experiences

why the two items chosen were important to them or their future careers; suggestions for improvement were also requested. This step served to strengthen the effects of the reflective process recommended by Kolb (1984) and Young (2002).

Project Assessment

To determine whether the project met its desired objectives, data collected from a survey were used to assess potential differences in students’ perceptions about their own selling skills. Open-ended answers collected as part of the reflec-tive process, along with responses collected from the corpo-rate partner, were reviewed for additional insights regarding the development of selling and coaching skills in a real-world environment.

METHOD

Data Collection and Samples

Survey data were collected from students enrolled in the class. Preproject surveys were administered in class imme-diately prior to the start of the project, with postproject sur-veys administered the class after completion of Role Play 3. Thirty-six of the 41 students enrolled in the class agreed to participate in the study, for a survey response rate of 88%. The majority of respondents were men (72.2%), with most students being seniors (94.4%) followed by juniors (8.6%). Seventy-eight percent of respondents were market-ing majors, followed by marketmarket-ing and management dou-ble-majors (11.1%) and other majors (8.3%). Most of the students (68.6%) reported previous sales experience. Stu-dent ages reflected the traditional college-age stuStu-dent. The demographic breakdown of the study sample was in line with the overall class demographic breakdown, which was 73% male. Slightly more respondents were seniors as com-pared to the overall class (83% seniors).

Reflection papers were completed in class approximately one week after the completion of Role Play 3. Students were informed several days in advance about the reflection

papers to provide adequate time to reflect on and consider responses.

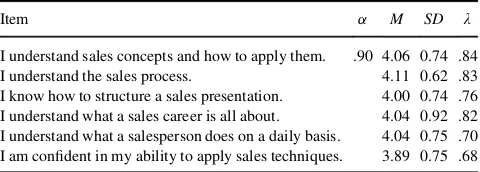

Quantitative Measures and Hypothesis

One dimension of the Intent to Pursue a Sales Career (ITPSC) Scale (Peltier, Cummins, Pomirleanu, Cross, & Simon, 2014) was used to assess potential changes in students’ perceptions as a result of the experiential learning project: sales knowledge. This dimension was chosen because it facilitates a self-report assessment of the students’ development of selling skills. Scale items can be seen in Table 2, along with descriptive statistics, factor loadings, and alpha values.

Sales knowledge was measured with six items designed to evaluate students’ perceptions of their individual sales skills. The original authors (Peltier et al., 2014) reported factor loadings of .72–.83 for this measure, with a reliability coefficient of .89. The results provide additional evidence of the factor structure and dimension reliability, with factor loadings of .68–.84 and an alpha coefficient of .90.

In developing the ITPSC Scale, Peltier et al. (2014) found that students’ scores increased significantly after an educational intervention in which guest speakers in a Prin-ciples of Marketing class covered sales-related content. Similarly, I hypothesized that students’ scores on sales knowledge would increase significantly at the end of the sales management experiential learning project, as com-pared to scores reported before the project started.

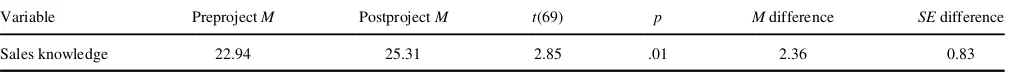

RESULTS

I usedttests to examine potential differences in means on sales knowledge (Table 3). It was expected that students’ perceptions about their own selling skills would increase significantly and positively. This expectation was sup-ported. sales knowledge experienced a significant and posi-tive increase, t(69) D2.85, p D .01, with students in the study perceiving a significant increase in their selling skills upon completion of the project.

Students’ Assessment of Project: Review of Qualitative Data

To gain additional insights into the students learning pro-cesses, the students’ final reflection papers were reviewed. Of the students who participated in the study, 28% found the experience to be excellent, with 67% suggesting the experience was good. Many students mentioned the real-world nature of the project as significant. A senior male marketing student, for example, noted that he appreciated the opportunity to test his skills in a realistic setting and gain more experience. Several students mentioned the value of doing something outside their comfort zones. Another

TABLE 2

Sales Knowledge Measure and Descriptive Statistics

Item a M SD λ

I understand sales concepts and how to apply them. .90 4.06 0.74 .84 I understand the sales process. 4.11 0.62 .83 I know how to structure a sales presentation. 4.00 0.74 .76 I understand what a sales career is all about. 4.04 0.92 .82 I understand what a salesperson does on a daily basis. 4.04 0.75 .70 I am confident in my ability to apply sales techniques. 3.89 0.75 .68

Note:All items from the Intent to Pursue a Sales Career (ITPSC) Scale (Peltier et al., 2014).λDstandardized factor loading.

CORPORATE-ACADEMIC PARTNERSHIPS 195

senior male marketing major summed it up this way: “It was the first time I had actual simulated real world experi-ence in class. Why aren’t all classes like this?”

Many of the comments reinforce the old axiom, practice makes perfect. In addition to identifying their enhanced knowledge of trial closes, handling objections, and asking questions, among other selling skills, students realized how to create value for customers. Preparing for the three role plays also helped the students develop coaching skills. Sev-eral students mentioned the usefulness of “learning how to motivate employees.” Another student learned to ask ques-tions as part of the coaching process, stating “you do not want to do all the talking. Make sure the person you are talking to understands and figure out if they [sic] have ideas.” As mentioned by one student, “when I become a sales manager in the future, I have a basic feel of how much coaching and support these reps need in order to succeed.”

In addition to positive comments, the students offered constructive criticism. The critical comments tended to fall into two related categories, with students seeking (a) more time to prepare and practice, and (b) technical information explained in greater detail. Many students mentioned spe-cific concerns about prices, margins, and turnover rates, as well as the intricacies of the DSL role. More class time spent on details should help students prepare more effec-tively, alleviate their concerns, and further improve devel-opment of linkages between theory and practice. Spreading the project over a larger portion of the semester may ease students’ feelings that material is being crammed.

Corporate Partner’s Assessment of Project: Review of Qualitative Data

To gain insights from the corporate partner’s perspective, participating Frito Lay personnel were asked several open-ended questions. I first sought to understand the benefits Frito Lay experienced. Many respondents noted the benefits associated with recruiting, noting, “[w]e were much more familar with the students and they were much more familar with us, making interviews more seamless.” In fact, the company extended six offers to students in the class, with five offers accepted. Additional offers for full-time posi-tions and internships were made outside the class, making this semester a highly effective recruiting experience for the company.

Recruiting was not the only benefit realized by the part-ner. Many respondents took great satisfaction in preparing

students for a career in sales, regardless of where those stu-dents gain employment. Others noted the benefits to the personnel who were presenting and participating in role plays. One person stated, “[i]t was a great opportunity for our sales team to practice their own presentation skills. In addition, it reinforced their subject matter knowledge.” Another suggested the process improved his own skills: “I find whenever you teach others, you automatically become more proficient yourself.”

The challenge mentioned most frequently by the Frito Lay partners related to time and resource commitments. Others mentioned being challenged by “sitting on the other side of the table” (i.e., playing the role of customer) during role plays. One class presenter noted the difficulty of pre-senting the material in a user-friendly way; industry jargon, company acronyms, and specialized reports proved chal-lenging to students, necessitating simplification of materials to improve the learning experiences for the students. Steps were taken to resolve this last issue during the semester. For example, acronyms were explained thoroughly and jar-gon was avoided. As long as all parties are aware of the issue, this particular challenge can be overcome relatively easily.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this article was to present a unique and innovative experiential learning project implemented in the sales management class as a corporate-academic partner-ship. As a result of being immersed in a corporate front-line sales manager role via content delivery, role plays, feed-back, and reflection, students gained a real-world experi-ence unlike any they had encountered previously in their college careers. Students learned and applied the role of the front-line sales manager and refined their selling skills. They learned how to (a) be effective coaches and motivate employees with a focus on the positive, (b) understand and address retailers’ concerns and pain points, (c) sell with a partner, and (d) develop creative solutions to problems. Moreover, they developed expertise in reading store heat maps and analytics and translating that information into a meaningful sales plan. By reviewing theoretical concepts, applying those concepts through role plays, and subse-quently reflecting on the process through feedback and reflection papers, the students are more likely to compre-hend and retain the knowledge gained (cf. Carver, 1996; Kolb, 1984; Young, 2002).

TABLE 3

Comparison of Sales Knowledge Means, Pre- and Postproject

Variable PreprojectM PostprojectM t(69) p Mdifference SEdifference

Sales knowledge 22.94 25.31 2.85 .01 2.36 0.83

As hypothesized, the quantitative test revealed that students’ perceptions of their own selling skills increased significantly and positively over the course of the project. Qualitative data provided by both students and Frito Lay personnel added support for this finding. Of course, critical to the success of this corporate-academic collaboration was the delivery of value to all stakeholders. Key benefits iden-tified by previous researchers (e.g., Danforth, 2006; Laugh-ton & Ottewill, 1998) were attained. As evidenced by the quantitative and qualitative results, students gained real-world experience and developed selling and coaching skills via the application of theory to practice. Interpersonal and communication skills improved, and students received a realistic preview of the front-line sales manager role. Because students developed skills and compentencies spe-cifically sought by the corporate partner, the firm realized an excellent return-on-investment with respect to recruiting and hiring. Firm personnel also benefitted from the opportu-nity to practice their presentation skills and reinforce sub-ject matter knowledge. Finally, the relationship between the university and the corporate partner was extended and solidified, thereby paving the way for future opportunities.

Areas for Improvement and Consideration

The qualitative review of the reflection papers revealed numerous positive learning experiences arising from this project. Certainly, however, areas for improvement exist. In particular, more class time spent on concepts and details should help students prepare more effectively, alleviate their concerns, and further improve development of the linkages between theory and practice. Spreading the project over a larger portion of the semester might ease students’ feelings that material is being crammed.

This project took place in a single classroom at a single university. Repeated iterations of the project, along with assessment of results, will enhance understanding of the efficacy of projects like the one presented here. Moreover, although this project was implemented in a sales manage-ment class, similar projects could be constructed for a vari-ety of business classes, and existing projects could be adapted to incorporate a corporate partner. Anselmi and Frankel (2004), for example, recommended the Extended Buying Center Game as an experiential exercise for market-ing, operations and purchasmarket-ing, and management and nego-tiations, with students working in teams to make purchasing decisions. An exercise such as this could be modified with a corporate partner by incorporating a pur-chase decision commonly faced by the partner, utilizing partner representatives in class, and providing students with partner feedback on their performance. Many class projects in many business disciplines would lend themselves to the addition of a corporate partner.

Recommendations for Instructors

The corporate partner worked closely with the instructor throughout this project, investing a great deal of time and energy in delivering a quality experience to students. Dur-ing initial meetDur-ings with the firm, it was clear that providDur-ing a valuable student learning experience was the primary goal for all involved. For instructors seeking to implement a sim-ilar project, the quality of the corporate partner and the will-ingness of that partner to commit resources (beyond monetary) is an important consideration. When the corpo-rate partner is heavily invested in the project and is willing to commit personnel to deliver content, take part in activi-ties, and deliver feedback, the student experience is greatly enhanced. It is helpful to meet with the partner well before the start of the semester, syllabus in hand, and discuss the goals and resources it would take to meet those goals. Also helpful is the presence of a point person within the corpora-tion who can serve as a coordinator and communicacorpora-tion conduit between the instructor and the company. Taking on a project such as this does require a substantial amount of work; with the right partner, however, that work is manage-able and worthwhile given the many benefits to all involved.

Conclusion

This experiential learning project achieved the set goals of providing students with a real-world experience, further developing students’ selling skills, and developing students’ coaching skills. Moreover, the project met the principles established for experiential learning by (a) creating an authen-tic experience, (b) involving students in the learning process, (c) having students’ reflect on what was learned, and (d) help-ing students connect the experience to future opportunity (Carver, 1996; Kolb, 1984; Young, 2002). Working with Frito Lay, the instructor was able to deliver a rich, meaningful real-world learning experience to students that also benefitted the university and the corporate partner.

REFERENCES

Allen, S., Wachter, R., Blum, M., & Gilchrist, N. (2009). Incorporating industrial kaizen projects into undergraduate team-based internships.

Business Education Innovation Journal,1, 22–31.

Anselmi, K., & Frankel, R. (2004). Modular experiential learning for busi-ness-to-business marketing courses.Journal of Education for Business,

79, 169–175.

Bennis, W. G., & O’Toole, J. (2005). How business schools lost their way.

Harvard Business Review,83(5), 96–104.

Blanchard, K., Lacinak, T., Tompkins, C., & Ballard, J. (2002).Whale done! The power of positive relationships.New York, NY: The Free Press. Carver, R. (1996). Theory for practice: A framework for thinking about

experiential education.The Journal of Experiential Education,19, 8–13. Chang, J. (2007). Sales by the schoolbook.Sales & Marketing

Manage-ment,159, 396–410.

CORPORATE-ACADEMIC PARTNERSHIPS 197

Danford, G. L. (2006). Project-based learning and international business education.Journal of Teaching in International Business,18, 7–25. Frontczak, N. T. (1998). A paradigm for the selection, use, and

develop-ment of experiential learning activities in marketing education. Market-ing Education Review,8(3), 25–33.

Kolb, D. A. (1984).Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Laughton, D., & Ottewill, R. (1998). Laying foundations for effective

learning from commissioned projects in business education.Education & Training,40, 95–101.

ManpowerGroup. (2013).2013 Talent shortage survey research results. Retrieved from http://www.manpowergroup.com/wps/wcm/connect/ manpowergroup-en/home/thought-leadership/research-insights/Talent-Sources/?WCM_Page.ResetAllDTRUE#.U-zVwPldWSo

McBane, D. A., & Knowles, P. A. (1994). Teaching communication skills in the personal selling class. Marketing Education Review, 4

(3), 41–48.

McHardy, B., & Marshall, J. C. (2003).Managing effort getting results: A coaching system for managers. Toronto, Canada: Self-Management Group.

Peltier, J. W., Cummins, S., Pomirleanu, N., Cross, J., & Simon, R. (2014). A parsimonious instrument for predicting intent to pursue a sales career: Scale development and validation.Journal of Marketing Education,36, 62–74.

Todd, A., & Ramachandran, R. (2007). Working through corporate and higher education partnerships.Chief Learning Officer,6(10), 74–76. Vazzana, M., & Jordan, J. (2013). Avoid sales coaching failure.TCD,67

(7), 46–49.

Walker, A., & Leary, H. (2009). A problem based learning meta anal-ysis: Differences across problem types, disciplines, and assessment levels.The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning,3, 12–43.

Young, M. R. (2002). Experiential learning D Hands-on C minds-on.

Marketing Education Review,12, 43–51.