Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:06

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

IFRS Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities: A Follow-Up

Study of Employer Expectations for Undergraduate

Accounting Majors

Sung Wook Yoon , Rishma Vedd & Christopher Gil Jones

To cite this article: Sung Wook Yoon , Rishma Vedd & Christopher Gil Jones (2013) IFRS Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities: A Follow-Up Study of Employer Expectations for Undergraduate Accounting Majors, Journal of Education for Business, 88:6, 352-360, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.727889

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.727889

Published online: 26 Aug 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 276

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.727889

IFRS Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities: A Follow-Up

Study of Employer Expectations for Undergraduate

Accounting Majors

Sung Wook Yoon, Rishma Vedd, and Christopher Gil Jones

California State University–Northridge, Northridge, California, USA

Although the most recent International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) work plan report from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission no longer includes a timetable for the U.S. adoption of global financial accounting standards, experts predict that the United States will transition to some form of convergence later this decade. In anticipation of the likely change, explicit coverage of IFRS was added to the Uniform Certified Public Accountant Examination in 2011. To identify what it will take for students to become IFRS-ready, this research continues a multiyear exploration into key IFRS student learning objectives, their relative importance, and strategies for incorporating them into the undergraduate accounting curriculum. Survey results suggest employer expectations have evolved.

Keywords:convergence, employer expectations, IFRS, U.S. GAAP, undergraduate accounting curriculum

As the global economy becomes increasingly borderless, the demand for a single international language of business has accelerated (American Institute of Certified Public Accoun-tants [AICPA], 2011; U.S. Securities and Exchange Com-mission [SEC], 2008). Already more than 12,000 companies in 120 countries have adopted International Financial Re-porting Standards (IFRS) in one form or another (AICPA, 2008). According to the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB, 2011, p. 4), “all remaining major economies have established time lines to converge with or adopt IFRSs in the near future.”

IFRS convergence is under way in the United States, albeit fitfully. On December 21, 2007, the SEC (2007) eliminated the reconciliation requirement for non-U.S. filers effective March 2008. Then in August 2008 the SEC (2008) proposed a roadmap for potential use of IFRS for U.S. financial report-ing. The original roadmap called for a phase in from 2014 to

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable input, and the staff of the Los Angeles Chapter of the California Society of CPAs for their cooperation and assistance in administering the survey.

Correspondence should be addressed to Christopher Gil Jones, Califor-nia State University–Northridge, Department of Accounting and Informa-tion Systems, 18111 Nordhoff Street, Northridge, CA 91330-8372, USA. E-mail: Christopher.Jones@csun.edu

2016, with early adoption for selected registrants as early as 2010. But with the financial markets in disarray at the end of 2008 and a change in the U.S. presidency at the beginning of 2009 that resulted in a shift in the political landscape, the pace of transition to IFRS has slowed. The SEC (2012) final staff report on theWork Plan for the Consideration of Incor-porating International Financial Reporting Standards into the Financial Reporting System for U.S. Issuersno longer mentions a timetable. Experts predict the U.S. will eventu-ally support some form of global financial standard but the timeline for convergence will be much longer than originally thought (Tysiac, 2012).

A slowing of the pace of IFRS convergence in the United States may be advantageous for academia. While much of the IFRS curricular research has focused on the educator perspective (Barth, 2008; Connolly & Llanes, 2008; Hor & Juchau, 2004), to date little research, other than our first study (Jones, Vedd, & Yoon, 2009), has examined the IFRS knowl-edge and skill set expectations from an employer’s view. In an effort to identify what those expectations might be and whether they have evolved, this research presents a follow-up study to our 2008 survey on key IFRS student learning objectives, their relative importance, and strategies for incor-porating them into the undergraduate accounting curriculum. Following the brief literature review, we describe our re-search methodology and respondent profile. Then we report

IFRS KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS, AND ABILITIES 353

findings and offer a short discussion of each research ques-tion enumerated in the literature review secques-tion. We conclude with implications for the undergraduate accounting curricu-lum in the United States. Major contributions of this research include (a) an updated summary of employer priorities re-garding key IFRS learning objectives, (b) an analysis of how employers expectations vary by demographic variable, and (c) recommended strategies for incorporating IFRS into the accounting curriculum.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Projected preparation levels of U.S. accounting graduates contrast sharply with employer expectations. With less than a quarter of new grads predicted to be IFRS-ready by 2012 (Connolly & Llanes, 2008), public accounting and industry face a shortage of skilled entry-level accountants. According to D. J. Gannon, director of Deloitte and Touche’s IFRS Cen-ter of Excellence, an estimated 40% of the Fortune Global 500 already use IFRS and that percentage will significantly increase in the next couple of years. A 2008 Deloitte survey of over 200 senior finance professionals underscored the need for additional IFRS education in the United States. Sixty-four percent of respondents indicated they lacked enough adequately trained IFRS professionals for U.S. operations. For non-U.S. operations, the skill shortage was not as pro-nounced; just 34% of respondents felt global accounting skills were inadequate (Deloitte & Touche, 2008). Mary Barth, a Stanford University professor of accounting and for-mer member of the IASB, asserted regarding the transition to IFRS, “The question is how, not whether, it will happen, and how, not whether, U.S. academics will participate” (Barth, 2008, p. 1176).

According to the SEC roadmap, adequate training in IFRS knowledge and skills is an essential precondition for final adoption of a global standard by the United States (SEC, 2008). Unfortunately, as the education and training section of the roadmap points out, existing education and training is “limited to or predominantly focused on current provisions of U.S. GAAP” (SEC, p. 29). The Commission suggests that “colleges and universities would need to include IFRS in their curricula” (SEC, p. 29).

While academia is still debating whether IFRS should be adopted (Albrecht, 2008; Bahnson & Miller, 2008; Fay, Bro-zovsky, Edmonds, Lobingier, & Hicks, 2008; Taub, 2007; Zeff, 2007), three external forces seem to be shaping the IFRS curricular integration dialog at the undergraduate level. First, the Big Four firms have all launched IFRS curric-ular initiatives (Deloitte & Touche, 2009; Harris, 2008; WebCPA, 2008). PricewaterhouseCoopers went so far as to specify IFRS-awareness levels for new recruits (Nilsen, 2008).

Accounting textbook publishers are the second external force molding the IFRS integration effort. Wiley, for

in-stance, has offered an online IFRS boot camp designed to “help instructors get up to speed on international conver-gence” since 2009 (Wiley, 2009, para. 1). The third exter-nal (and probably most significant) outside influence on the IFRS curricular integration is the public accounting licensing exam itself. In May 2008, the AICPA expressed its intent to incorporate global accounting standards into the CPA exam requiring candidates to become bilingual in both U.S. Gen-erally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and IFRS. Beginning in 2011, the Uniform CPA Examination was re-vamped with a new structure, format, and comparative con-tent between IFRS and U.S. GAAP. Under the new Con-tent and Skill Specification Outlines, CPA exam candidates are expected to identify and understand the differences be-tween financial statements prepared on the basis of U.S. GAAP and IFRS. Candidates are also required to demon-strate proficiency in first-time adoption of IFRS (AICPA, 2009).

This new reality puts significant pressure on academic units providing accounting education. A recent survey of accounting departments at 200 universities throughout the United States indicated significant change in the interme-diate accounting course sequence is underway in response to information overload from IFRS integration (Davidson & Francisco, 2009). Additionally, as part of the undergradu-ate accounting curriculum redesign effort, many institutions have begun to introduce comprehensive research cases re-quiring comparative analysis of U.S. GAAP and IFRS (John-son & Halabi, 2011).

Based on our literature review and results from our pre-vious study, we developed the following research questions for further inquiry:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): How important is integrating IFRS in the undergraduate accounting curriculum?

RQ2:What strategy should be used to incorporate IFRS into the undergraduate accounting curriculum?

RQ3: What relative weight should IFRS and U.S. GAAP content be given in undergraduate accounting classes until the U.S. converges with (or adopts) IFRS?

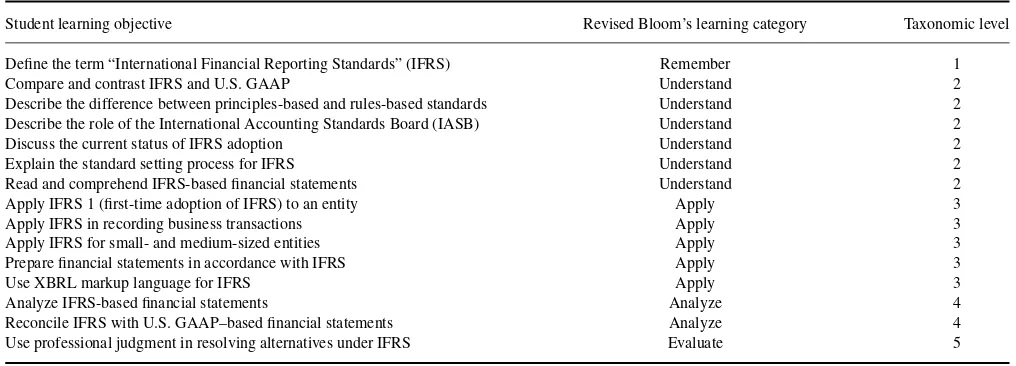

RQ4:How important is it for entry-level accounting job can-didates to have a suite of IFRS knowledge and skills (see Table 1)?

RQ5: Do public accounting firms have higher expecta-tions regarding IFRS competencies than nonaccounting firms? What about large organizations versus small- or medium-sized organizations? Or companies with for-eign operations versus companies that only operate do-mestically?

RQ6:Do large organizations have more interest in Extensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL) for IFRS than small- or medium-sized organizations?

RQ7: Do small- and medium-sized organizations expect graduates to know more about IFRS for “small- or medium-sized entities” than do large organizations?

TABLE 1

IFRS Student Learning Objectives Categorized by Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy

Student learning objective Revised Bloom’s learning category Taxonomic level

Define the term “International Financial Reporting Standards” (IFRS) Remember 1

Compare and contrast IFRS and U.S. GAAP Understand 2

Describe the difference between principles-based and rules-based standards Understand 2 Describe the role of the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) Understand 2

Discuss the current status of IFRS adoption Understand 2

Explain the standard setting process for IFRS Understand 2

Read and comprehend IFRS-based financial statements Understand 2

Apply IFRS 1 (first-time adoption of IFRS) to an entity Apply 3

Apply IFRS in recording business transactions Apply 3

Apply IFRS for small- and medium-sized entities Apply 3

Prepare financial statements in accordance with IFRS Apply 3

Use XBRL markup language for IFRS Apply 3

Analyze IFRS-based financial statements Analyze 4

Reconcile IFRS with U.S. GAAP–based financial statements Analyze 4 Use professional judgment in resolving alternatives under IFRS Evaluate 5

Note.In the original taxonomy, Bloom used noun descriptors for the learning levels (Bloom, Englehart, Furst, Hill, & Krathwohl, 1956); these have been

replaced with action verbs. Bloom’s learning categories, as revised by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001), are now (a) remember (formerly knowledge), (b) understand (formerly comprehension), (c) apply (formerly application), (d) analyze (formerly analysis), (e) evaluate (formerly evaluation), and (f) create (formerly synthesis). Levels 5 and 6 were swapped. Evaluate, originally Level 6, is now considered Level 5 and create is now Level 6.

METHOD

Survey Instrument and Sample Selection

To address the specific research questions posed by this study, we updated the questionnaire from our initial survey (Jones et al., 2009). The 2008 survey instrument was de-veloped using previous IFRS surveys (Deloitte & Touche, 2008; PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2006) and relevant literature (Barth, 2008; Nilsen, 2008) as a guide. The updated ques-tionnaire (available from the first author) was pilot tested with the department accounting faculty at California State University, Northridge, and any suggestions incorporated in the final instrument. During summer 2010, the questionnaire was administered to members of the California Society of Certified Public Accountants (CalCPA) in the Southern Cal-ifornia region. The Los Angeles Chapter of CalCPA emailed approximately 10,000 survey requests and collected the sur-vey results. Due to the size of the mailing, CalCPA did not collect data on returned emails or blocked delivery due to spam filtering. A total of 166 members responded to the sur-vey via web. Frequencies may tally to less than 166 as not every participant answered every question.

RESULTS

Respondent Profile

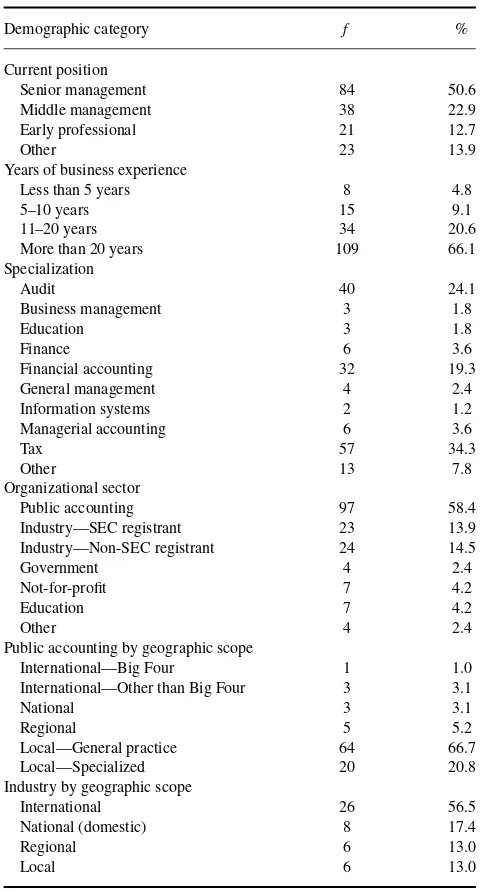

Table 2 summarizes demographic information regarding po-sition title, experience, specialization, employment sector, and geographic scope for the 166 useable responses. The typical respondent was a senior manager in a local public accounting firm with 20+years of experience. Primary areas

of specialization were either tax (34.3%), audit (24.1%), or financial accounting (19.3%).

Compared to the previous survey, respondents in this study may have been more familiar with international accounting due to the proportionately higher affiliation levels with na-tional or multinana-tional firms (nana-tional: 17.4% in 2010 vs. 9.1% in 2008; multinational: 56.5% in 2010 vs. 18.2% in 2008).

Research Question 1: Employer Perspective on IFRS Coverage

Most survey participants (90.9%) believed that IFRS cov-erage is important enough that it should already be part of the existing undergraduate accounting curriculum (Table 3). About a third of respondents reported that IFRS integration was very important (18.9%) or extremely important (14.6%). A little more than a third (34.8%) responded that IFRS cover-age was important, with 22.6% of respondents indicating that curricular integration was somewhat important. Only 9.1% of survey participants did not feel IFRS should be integrated into the curriculum at all. Findings are consistent with our previous research.

Research Question 2: Preferred Integration Strategies

Table 4 presents recommended strategies for incorporating IFRS into the accounting curriculum. Opinion was divided. A little more than a quarter (27.3%) of respondents would integrate IFRS into all financial accounting coursework, start-ing with the principles course. A slightly lower percentage (25.5%) took a broader view, preferring to integrate IFRS into

IFRS KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS, AND ABILITIES 355

TABLE 2

Descriptive Statistics (N=166)

Demographic category f %

More than 20 years 109 66.1

Specialization

Public accounting by geographic scope

International—Big Four 1 1.0

International—Other than Big Four 3 3.1

National 3 3.1

Note.SEC=U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

TABLE 4

Recommended Strategies for Incorporating IFRS into the Curriculum

Curricular strategy f %

Integrate IFRS into allfinancial accountingcourses 44 27.3 Integrate IFRS into allaccounting programcoursework 41 25.5 Stand-alone IFRS course 33 20.5 Integrate IFRS into only theintermediateaccounting series 22 13.7 Integrate IFRS into just theinternationalaccounting course 14 8.7

Other 7 4.3

Note. Table shows responses to survey question, “What strategy

would you recommend for incorporating IFRS into the undergradu-ate accounting curriculum?” IFRS=International Financial Reporting Standards.

all accounting coursework. This would mean IFRS coverage in auditing, tax, managerial accounting, and accounting infor-mation systems, in addition to the financial accounting series. About 20% of employers prefer a stand-alone IFRS course, while 13.7% recommend an intermediate-accounting-series only approach. The lack of consensus for a preferred integra-tion strategy parallels our prior survey results.

Research Question 3: Relative Coverage of IFRS Versus U.S. GAAP

Until the United States actually converges with IFRS, the ma-jority (57.1%) of respondents believe more emphasis should be placed on U.S. GAAP in the classroom than on IFRS. Table 5 presents respondent preferences for relative weights of IFRS/U.S. GAAP coverage in 10% increments. Of those respondents favoring more U.S. GAAP coverage than IFRS, the mode was 70% U.S. GAAP–30% IFRS (f =29). A little less than one third (31.6%) of respondents would give equal treatment to IFRS and U.S. GAAP. Only 10.1% of respon-dents felt that more weight should be given to IFRS. Two respondents (1.3%) felt that IFRS should be covered exclu-sively. In contrast, two respondents (1.3%) felt that only U.S. GAAP should be covered until the United States converges with IFRS.

TABLE 3

Importance of IASB Curricular Integration

Not important

Note.Table shows responses to survey question, “How important is integrating IFRS into the undergraduate accounting curriculum?” Responses were

rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale with responses ranging from 1 (not important) to 5 (extremely important). IFRS=International Financial Reporting Standards.

TABLE 5

Relative Weight for U.S. GAAP Versus IFRS Coverage

Relative weight f %

100% U.S. GAAP 2 1.3

10% IFRS–90% U.S. GAAP 18 11.4

20% IFRS–80% U.S. GAAP 24 15.2

30% IFRS–70% U.S. GAAP 29 18.4

40% IFRS–60% U.S. GAAP 17 10.8

50% IFRS–50% U.S. GAAP 50 31.6

60% IFRS–40% U.S. GAAP 5 3.2

70% IFRS–30% U.S. GAAP 6 3.8

80% IFRS–20% U.S. GAAP 4 2.5

90% IFRS–10% U.S. GAAP 1 0.6

100% IFRS 2 1.3

Note.GAAP=Generally Accepted Accounting Principles; IFRS=

International Financial Reporting Standards.

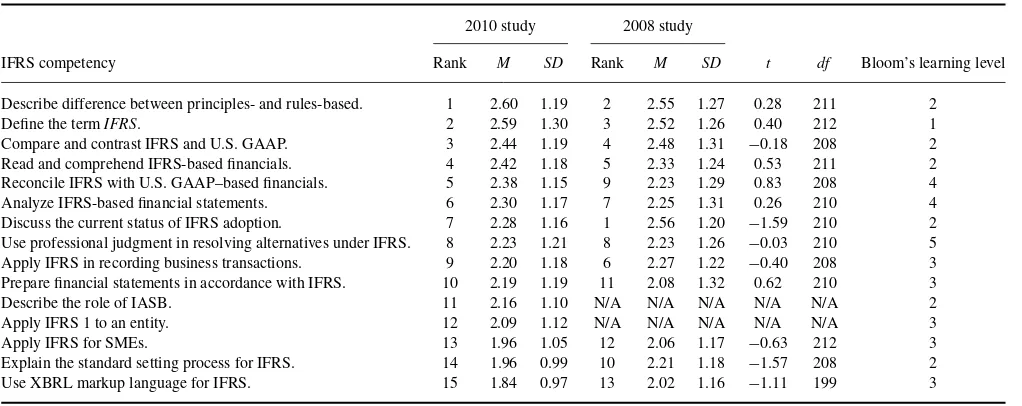

Research Question 4: IFRS Knowledge and Skills

Survey participants were presented with a list of 15 IFRS learning objectives (see Table 1) and asked to rate the importance of each competency for new-hires using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 5 (extremely important). Thirteen of the 15 IFRS learning objectives were derived from our previous survey research and were largely based on employer expectations for new hires (Nilsen, 2008). Two new learning objectives were added to the questionnaire in response to recent inclusion of

the items in the 2011 Uniform CPA Exam (AICPA, 2009). These two additional learning objectives are “Describe the role of the IASB” and “Apply IFRS 1 to an entity” (IFRS 1 addresses first-time adoption of IFRS by an entity).

Table 6 summarizes employer expectations concerning the 15 IFRS competencies. Learning objectives are listed in descending order by importance mean and given a simulated rank order. Mean ratings for each learning objective are com-pared side by side with our 2008 study. Results of pairwise

t-tests of the differences in the means indicate importance rat-ings of the 13 IFRS knowledge objectives are not statistically different from the earlier study.

Respondents rated 12 of the IFRS competencies as some-what important (range=2.00–2.99). Of the 12 learning ob-jectives, two clustered above the midpoint between anchors on the Likert-type scale (2.5); these were (a) describe the dif-ference between principles-based and rules-based standards (M=2.60,SD=1.19) and (b) define the termIFRS(M= 2.59,SD=1.30; Table 6). Three of the 15 IFRS competen-cies were rated as not important (range=1.00–1.99)—apply IFRS for SMEs, explain the standard setting process for IFRS and use XBRL markup language for IFRS.

For the most part, simulated importance rankings for IFRS learning objectives were comparable with those found in our 2008 study. Top-rated IFRS competencies such as (a) de-scribe the difference between principles-based and rules-based standards, (b) define the term “international finan-cial reporting standards,” (c) compare and contrast IFRS and U.S. GAAP, and (d) read and comprehend IFRS-based financial statements were ranked second through fifth in

TABLE 6

Importance of IFRS Knowledge and Skills

2010 study 2008 study

IFRS competency Rank M SD Rank M SD t df Bloom’s learning level

Describe difference between principles- and rules-based. 1 2.60 1.19 2 2.55 1.27 0.28 211 2

Define the termIFRS. 2 2.59 1.30 3 2.52 1.26 0.40 212 1

Compare and contrast IFRS and U.S. GAAP. 3 2.44 1.19 4 2.48 1.31 −0.18 208 2 Read and comprehend IFRS-based financials. 4 2.42 1.18 5 2.33 1.24 0.53 211 2 Reconcile IFRS with U.S. GAAP–based financials. 5 2.38 1.15 9 2.23 1.29 0.83 208 4 Analyze IFRS-based financial statements. 6 2.30 1.17 7 2.25 1.31 0.26 210 4 Discuss the current status of IFRS adoption. 7 2.28 1.16 1 2.56 1.20 −1.59 210 2 Use professional judgment in resolving alternatives under IFRS. 8 2.23 1.21 8 2.23 1.26 −0.03 210 5 Apply IFRS in recording business transactions. 9 2.20 1.18 6 2.27 1.22 −0.40 208 3 Prepare financial statements in accordance with IFRS. 10 2.19 1.19 11 2.08 1.32 0.62 210 3

Describe the role of IASB. 11 2.16 1.10 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 2

Apply IFRS 1 to an entity. 12 2.09 1.12 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 3

Apply IFRS for SMEs. 13 1.96 1.05 12 2.06 1.17 −0.63 212 3

Explain the standard setting process for IFRS. 14 1.96 0.99 10 2.21 1.18 −1.57 208 2 Use XBRL markup language for IFRS. 15 1.84 0.97 13 2.02 1.16 −1.11 199 3

Note.Sample size (n) ranged from 143 to 150 because several respondents did not answer the questionnaire completely, leaving blank one or more

importance rating questions. Values for calculation of rating average were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 5 (extremely

important). For the two items added to the 2010 questionnaire (IASB Role and IFRS 1),t-tests were infeasible; rank, rating average, standard deviation, and

tvalues are labeled N/A for these items. IFRS=International Financial Reporting Standards; IASB=International Accounting Standards Board; SME= small- and medium-sized enterprise; XBRL=Extensible Business Reporting Language.

IFRS KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS, AND ABILITIES 357

our first survey and first through fourth in this research. Low importance–rated IFRS learning objectives apply IFRS for SMEs and use XBRL markup language for IFRS were bottom-ranked at thirteenth and fifteenth, respectively, con-sistent with bottom-rankings from our previous survey. The only major shift in rankings was the learning objective “Dis-cuss the current status of IFRS adoption,” which ranked first in our first survey, but ranked seventh in this research. Per-haps the clarification from the SEC in 2010 regarding the SEC convergence work plan made adoption seem more like a nonissue than it was in 2008.

The results of the 2010 survey confirm the 2008 sur-vey findings that employers already expect undergraduate accounting majors to have a conceptual-level awareness of IFRS. Where the 2010 survey differs is in the cognitive pro-gression from simple awareness (Bloom’s Level 1) to ap-plication (Bloom’s Level 3; Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). Employers now expect entry-level accountants to have a rudi-mentary working knowledge of IFRS–U.S. GAAP differ-ences. Based on the results of the 2010 survey, accounting students, at a minimum, are expected to be able to (a) define the acronym IFRS, (b) compare and contrast principles-based and rules-based approaches to accounting standards, and (c) understand IFRS financial statements well enough to recon-cile to U.S. GAAP. At this time, employers do not expect accounting undergraduates to account for business transac-tions using IFRS, nor prepare financial statements solely in accordance with IFRS. Employers have little interest in whether accounting majors know how to apply a subset of IFRS to small- to medium-sized entities, work with XBRL for IFRS, or understand IASB standard setting.

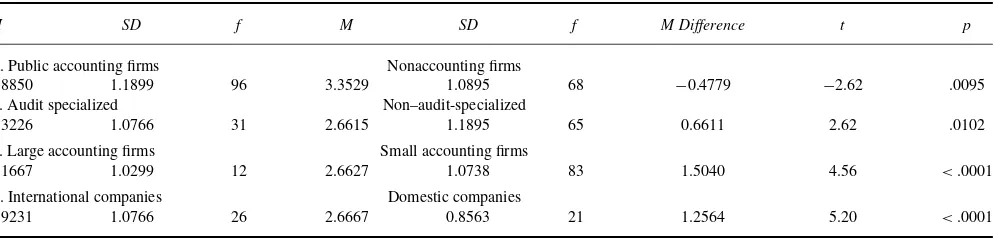

Research Question 5: IFRS Coverage Importance by Employer Type

To answer RQ5 regarding the importance of IFRS cover-age by employer demographic variable, pairwiset-tests were used to compare mean differences. Results of the inferential analyses are presented in Table 7.

Public accounting versus nonaccounting firms. We

hypothesized that public accounting firms (with their focus

on the application of financial reporting standards) would place greater importance on integrating IFRS into the ac-counting curriculum than other acac-counting employers. As Table 7 Panel A depicts, the data did not support our hy-pothesis. Public accounting firms assign significantly lower importance,t(162) = −2.62,p<.0095, to IFRS coverage

in the curriculum (M =2.8850,SD=1.1899) than nonac-counting employers (M =3.3529,SD=1.0895). One pos-sible explanation is that the majority of public accounting respondents (87.5%) in the sample were affiliated with lo-cal practices rather than regional, national, or international public accounting firms. Local firms rarely serve SEC reg-istrants. In contrast, about half of the industry respondents were from companies required to file under SEC regulations and guidelines.

Audit specialized versus non–audit-specialized

firms. With a task focus tied to financial reporting

stan-dards, we conjectured that respondents specializing in audit would place greater emphasis on IFRS competence than do other accounting and business specializations. As Table 7 Panel B indicates, auditors do report a significantly higher importance,t(94)=2.62,p<.0102, for IFRS coverage in

the curriculum (M=3.3226,SD=1.0766) than nonauditors (M=2.6615,SD=1.1895).

Large accounting firms versus small accounting

firms. By virtue of their current role in the global

econ-omy, we hypothesized that large accounting firms would rate IFRS coverage more important than would small accounting firms. Respondents from large accounting firms (see Table 7 Panel C) did, indeed, report a higher importance rating for IFRS coverage (M =4.1667,SD=1.0299) than did small accounting firms (M =2.6627, SD =1.0738), and t-tests revealed a significant difference, t(93)= 4.56,p <.0001

between importance means for these two groups, lending support to the hypothesis that large accounting firms place greater emphasis on IFRS that do smaller firms.

International companies versus domestic

compa-nies. We also hypothesized that international companies

would have more interest in IFRS coverage than domestic

TABLE 7

Comparison of International Financial Reporting Standards Curricular Importance, by Employer Characteristic

M SD f M SD f M Difference t p

A. Public accounting firms Nonaccounting firms

2.8850 1.1899 96 3.3529 1.0895 68 −0.4779 −2.62 .0095

B. Audit specialized Non–audit-specialized

3.3226 1.0766 31 2.6615 1.1895 65 0.6611 2.62 .0102

C. Large accounting firms Small accounting firms

4.1667 1.0299 12 2.6627 1.0738 83 1.5040 4.56 <.0001

D. International companies Domestic companies

3.9231 1.0766 26 2.6667 0.8563 21 1.2564 5.20 <.0001

TABLE 8

Importance of XBRL for International Financial Reporting Standards, by Employer Size

Large organizations Small organizations

M SD f M SD f MDifference t p

2.1842 1.0096 38 1.7143 0.9283 105 0.4699 2.61 .0099

businesses. As expected, international companies did report a higher importance for IFRS coverage (M = 3.9231,SD = 1.0766) than their domestic counterparts (M =2.6667,

SD=0.8563; see Table 7 Panel D). Mean differences in im-portance ratings were significant,t(45)=5.20,p<.0001.

As with large public accounting firms, it would appear inter-national companies do place a higher importance on IFRS curricular integration.

Research Question 6: Importance of XBRL for IFRS by Employer Size

In 2009, the SEC initiated mandatory XBRL tagging of fi-nancial statements for large capitalization accelerated filers (i.e., common equity float>$5 billion). All other large filers

were required to implement XBRL tagging in 2010; smaller firms were required to phase in what the SEC calls interactive data to improve financial reporting in 2011 (SEC, 2009). An XBRL tag set specific to IFRS is already in use. Given the order of the XBRL phase-in timetable, we hypothesized that large organizations would have more interest in education on XBRL for IFRS than small organizations. Table 8 shows that large organizations (M=2.1842,SD=1.0096), did rate XBRL for IFRS coverage more important than small organi-zations (M =1.7143,SD=0.9283). Results of a pair-wise

t-test of the difference between these two means was signif-icant,t(141) =2.61, p<.0099, providing support for the

hypothesis.

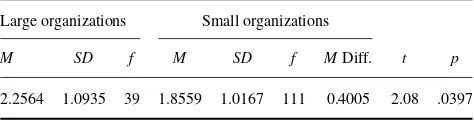

Research Question 7: Importance of IFRS for SMEs by Employer Size

Both the FASB and IASB are involved in initiatives to pro-vide scaled-back versions of GAAP, dubbed little GAAP. On July 9, 2009, the IASB (2009) published a subset of IFRS de-signed for use by small- and medium-sized entities (SMEs). According to the IASB, SMEs are estimated to represent more than 95% of all companies. Because IFRS for SMEs is designed to serve this constituency, we speculated that small- and medium-sized organizations would place more importance on the IFRS for SMEs learning objective than would large organizations.

Table 9 presents results from the statistical analysis comparing the mean importance rating for IFRS for SMEs between small organizations and large organizations. Contrary to our expectation, large organizations, in fact,

TABLE 9

Importance of International Financial Reporting Standards for Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises,

by Employer Size

Large organizations Small organizations

M SD f M SD f MDiff. t p

2.2564 1.0935 39 1.8559 1.0167 111 0.4005 2.08 .0397

reported a significantly higher, t(148) = 2.08, p <.0397,

importance rating for IFRS for SMEs coverage (M=2.2564,

SD =1.0935) than did small organizations (M = 1.8559,

SD = 1.0167). Perhaps smaller organizations, lacking the resources of larger entities, are less aware of recent developments in accounting standards targeted to the needs of SMEs. Additional research is needed to confirm this.

DISCUSSION

Limitations

Although the 1.66% useable response rate (N=166) was typ-ical for a web survey with only a single email request for par-ticipation, external validity of survey results may suffer from a nonresponse bias. A follow-up email to members would have allowed a comparison of first responders to late respon-ders, providing a surrogate for determining whether nonre-sponders would have self-reported differently. Although the sponsoring organization was gracious enough to support the study by initiating the emails and hosting the web question-naire, to avoid list fatigue it was understandably reluctant to send a second email. Nonetheless, this study’s findings are, on the whole, consistent with our 2008 study, both in terms of skill importance ratings and respondent demographics. In the 2008 study, the web survey response rate was 23.6% (N=66). Given that for the most part survey results paral-lel our previous survey (albeit with two additional learning objectives), we believe the sample was fairly representative of a cross-section of employers in large U.S. urban areas that hire accounting undergraduates.

CONCLUSIONS

This research presents a follow-up study to an earlier sur-vey on key IFRS student learning objectives, their relative importance, and strategies for incorporating them into the undergraduate accounting curriculum. In the 2008 study, the survey frame was narrowly defined as employers who have hired or intended to hire four-year accounting undergraduates from a large urban public university located in the greater Los Angeles metropolitan area for full-time employment

IFRS KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS, AND ABILITIES 359

and internships. In the follow-on study, the survey frame was expanded; respondents were drawn from the 10,000 plus membership of the Los Angeles Chapter of the CalCPA. De-scriptive and inferential analyses of the survey data yielded the following conclusions summarized subsequently.

IFRS Coverage Prior to Full Convergence

Although the SEC has not yet formally adopted IFRS for domestic filers, most practicing accountants (90.9%) believe coverage of IFRS is important enough to be included in the curriculum now.

Curricular Integration Strategies

Opinions on how to incorporate IFRS in the accounting un-dergraduate curriculum are divided. A little over a fourth of respondents would embed IFRS in the financial accounting coursework; another fourth would integrate IFRS into all the accounting coursework. Still others prefer a stand-alone IFRS course (20.5%). Somewhat less favored is integrating IFRS into just the intermediate accounting series (13.7%). The least favored integration strategy was incorporating IFRS into an international accounting course (8.7%).

Standards Weighting: U.S. GAAP Versus IFRS

With regard to the relative topic weight for the two standards, at this time the majority of employers (57.1%) prefer more emphasis be given to U.S. GAAP in the classroom than IFRS. Of those respondents favoring more U.S GAAP coverage than IFRS, the preference is for a 70% U.S. GAAP–30% IFRS split. A little less than one third (31.6%) of respondents would give equal treatment to IFRS and U.S. GAAP.

Core IFRS Knowledge and Skills

Based on the results of this follow-up survey, it appears employers already expect undergraduate accounting majors to have some conceptual-level awareness of IFRS and a rudimentary working knowledge of IFRS–U.S.GAAP dif-ferences. Not unexpectedly, required IFRS competencies are viewed from a U.S. GAAP perspective (GAAP-centric) with IFRS defined in relationship to the U.S. GAAP.

IFRS Importance by Employer Type

As expected, respondents specializing in audit do, in fact, at-tach higher importance to IFRS coverage than nonauditors. Large accounting firms place greater emphasis on IFRS than do smaller firms; likewise, international firms consider IFRS more important than do domestic companies. At the learning objective level, large accounting firms consider XBRL for IFRS to be more important than do small firms. Contrary to our expectations, public accounting firms place less im-portance on IFRS coverage than does industry; small firms place less importance on IFRS for SMEs than do large firms.

Implications for the Undergraduate Accounting Curriculum

This study examined the curricular impact of IFRS on un-dergraduate accounting education. Several recommendations emerge from the findings.

Integrate IFRS at a deeper level. The survey results

are clear that employers expect today’s undergraduates to have more than a general awareness of global financial re-porting standards. Graduating seniors should be able to de-fine and describe IFRS, compare and contrast principles- and rules-based approaches to accounting standards, and under-stand IFRS financial statements well enough to reconcile to U.S. GAAP. This exceeds PricewaterhouseCoopers’s some-what progressive recruiting expectation that (a) sophomores be able to explain the uses of IFRS and discuss its future importance; and (b) juniors and seniors be able to discuss the current status of IFRS adoption, articulate the sources of U.S. GAAP and IFRS, describe an example of IFRS fi-nancial statements, and identify and example of a difference between U.S. GAAP and IFRS (Nilsen, 2008). Resources for including IFRS coverage at the deeper level suggested by this study are currently available from the large public accounting firms and have recently been incorporated into financial accounting textbooks from major publishers.

Employers are ambivalent about which curricular inte-gration strategy to use. Making room in the undergraduate curriculum for an additional specialized accounting course may be difficult given college–university limitations on the maximum number of semester–quarter units allowed in a de-gree program (Davidson & Francisco, 2009). The solution adopted at our institution was to expand the required inter-mediate series from seven semester units to nine semester units and eliminate the stand-alone IFRS elective.

With regard to relative weight given to the two account-ing standards, we recommend devotaccount-ing 70% of class time in the undergraduate curriculum to U.S. GAAP, leaving 30% for IFRS. Recent intermediate accounting textbook offer-ings (with their increased IFRS coverage) should facilitate the move to a higher proportionate coverage of international standards.

Focus on key IFRS exit competencies. The

simu-lated rankings of the IFRS knowledge objectives provide a good starting point for curricular emphasis. In the near term, we recommend the top-10 learning objectives be empha-sized with additional attention to the first five: (a) describe the difference between principles- and rules-based standards, (b) defineIFRS, (c) compare U.S. GAAP to IFRS, (d) read and comprehend IFRS financials, (e) reconcile IFRS to U.S. GAAP, (f) analyze IFRS financials, (g) discuss IFRS adoption status, (h) develop professional judgment needed to apply principle-based standards, (i) record business transactions using IFRS, and (j) prepare financial statements in accor-dance with IFRS.

At or about the time U.S. GAAP and IFRS do con-verge, students should be taught how to apply IFRS 1 (First-time Adoption of IFRS; International Accounting Standards Board, 2003). Students would also then be expected to demonstrate an understanding of the international account-ing standards settaccount-ing process and the role of the IASB. Little, if any, class coverage should be devoted to IFRS for SMEs or XBRL for IFRS.

Help faculty retool for IFRS. Deep integration of IFRS

content is no small undertaking. Big Four firms have taken the initiative to provide course support material for the massive re-education campaign of existing faculty. Textbook publish-ers have increased IFRS coverage. What is needed now is more institutional support in the form of release time, faculty development funds, and course redevelopment stipends to update existing courses and curriculum. Such support would help to insure that the growing momentum in academia to in-tegrate IFRS into the curriculum continues as the profession evolves toward a single set of high-quality global standards.

REFERENCES

Albrecht, D. (2008). Why IFRS won’t work in the United States. Retrieved from http://profalbrecht.wordpress.com/2008/09/26/why-ifrs-wont-work-in-united-states/

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (2008).

Inter-national financial reporting standards: Questions and answers. Retrieved

from http://www.ifrs.com/updates/aicpa/ifrs faq.html

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (2009).

Con-tent and skill specifications for the uniform CPA examination. Ewing, NJ:

Author.

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). (2011).

Inter-national financial reporting standards (IFRS): An AICPA backgrounder.

Retrieved from http://www.ifrs.com/pdf/IFRSUpdate V8.pdf

Anderson, L., & Krathwohl, D. A. (2001).Taxonomy for learning, teaching

and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives.

New York, NY: Longman.

Bahnson, P. R., & Miller, P. B. W. (2008). The spirit of accounting: What good are principles without principles?Accounting Today,22(18), 16–17. Barth, M. E. (2008). Gloxbal financial reporting: Implications for U.S.

aca-demics.The Accounting Review,83, 1159–1179.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.) (1956).Taxonomy of education objectives: Handbook I:

Cognivitive domain. New York, NY: David McKay.

Connolly, T., & Llanes, S. (2008). University professors weigh in on building IFRS into curricula: Small number of universities will be ready for 2008– 2009 academic year, according to KPMG-AAA survey.KPMG News. Retrieved from http://www2.prnewswire.com/cgi-bin/stories.pl?ACCT= 104&STORY=/www/story/09-04-2008/0004878725&EDATE=;. Davidson, L. H., & Francisco, W. H. (2009). Changes to the intermediate

accounting course sequence.American Journal of Business Education, 2(7), 55–59.

Deloitte & Touche. (2008).2008 IFRS survey: Where are we today? Re-trieved from http://www.iasplus.com/en/binary/dttpubs/2008ifrssurvey. pdf/view

Deloitte & Touche. (2009).Deloitte’s IFRS university consortium. Retrieved from http://www.deloitte.com/us/ifrs/consortium

Fay, R., Brozovsky, J., Edmonds, J., Lobingier, P., & Hicks, S. (2008). Incorporating International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) into

intermediate accounting. Retrieved from http://www.deloitte.com/assets/

Dcom-UnitedStates/Local%20Assets/Documents/us assurance Incorpor ating%20IFRS%20into%20Intermediate%20Accounting.pdf

Harris, R. (2008, May 22). Big Four make big plans for IFRS.CFO.com. Retrieved from http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/11434822

Hor, J., & Juchau, R. (2004, July).Internationalising the financial

account-ing curriculum: A survey of course content and coverage. Paper presented

at the Fourth Asia Pacific Interdisciplinary Research in Accounting Con-ference, Singapore.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2003).First-time adop-tion of Internaadop-tional Financial Reporting Standards. Internaadop-tional

Finan-cial Accounting Standard No. 1. London, England: Author.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2009).IFRS for SMEs.

Work plan for IFRSs. Retrieved from http://www.ifrs.org/Current+

Projects/IASB+Projects/Small+and+Medium-sized+Entities/Small+ and+Medium-sized+Entities.htm

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). (2011).International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), IASC Foundation (IASCF): Who

we are and what we do. Retrieved from http://www.ifrs.org/NR/rdonlyres/

1D35BB5F-6E59-446F-9861-A84F9288CBB4/0/Who we areJuly11.pdf Johnson, G. R., & Halabi, A.K. (2011). The accounting undergraduate

capstone: Promoting sysnthesis, refelction, transition, and competencies.

Journal of Education for Business,86, 266–273.

Jones, C., Vedd, R., & Yoon, S. (2009). Employer expectations of account-ing undergraduates’ entry-level knowledge and skills in global financial reporting.American Journal of Business Education,2(6), 85–101. Nilsen, K. (2008). On the verge of an academic revolution: How IFRS is

affecting accounting education.Journal of Accountancy,206(6), 82–85. PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2006).IFRS: Embracing change. Retrieved from

http://www.soxfirst.com/50226711/IFRS%20company%20survey%5B1 %5D.pdf

Taub, S. (2007, September 25). IFRS and GAAP: The good and the bad.

Compliance Week. Retrieved from http://www.complianceweek.com.

Tysiac, K. (2012, July 13). SEC report offers detailed look at IFRS.

Jour-nal of Accountancy. Retrieved from http://www.journalofaccountancy.

com/News/20125815.htm

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (2007).Acceptance from foreign private issuers of financial statements prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards without reconciling

to U.S. GAAP[Release Nos. 33–8879; 34–57026; International Series

Release No. 1306; File No. S7-13-07]. Washington, DC: Author. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (2008).Roadmap for

the potential use of financial statements prepared in accordance with

international financial report standards by U.S. issuers[Release Nos.

33–8982; 34–58960; File No. S7-27-08]. 17 CFR Parts 210, 229, 230, 240, 244 and 249. Washington, DC: Author.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (2009). Interactive

data to improve financial reporting[Release Nos. 33–9002; 34–59324;

39–2461; IC-28609; File No. S7-11-08] 17 CFR Parts 229, 230, 232, 239, 240 and 249. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2009/33-9002.pdf

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (2010).Work plan for the consideration of incorporating International Financial Reporting

Stan-dards into the financial reporting system for U.S. issuers. Washington,

DC: Author.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). (2012).Work plan for the consideration of incorporating international financial reporting stan-dards into the financial reporting system for U.S. issuers: Final staff

report. Washington, DC: Author.

WebCPA. (2008, May 19). Ernst & Young to develop IFRS

curricu-lum.Accounting Today for the WebCPA.Retrieved from http://www.

accountingtoday.com/news/27792-1.html

Wiley. (2009).IFRS boot camp. Retrieved from http://www.wileyauthor teamforsuccess.com/news.php

Zeff, S. A. (2007). Some obstacles to global financial reporting comparability and convergence. The British Accounting Review, 4, 290–302.