Artikel ini menawarkan optimisme terhadap smart city sebagai wujud bekerjanya networked society dalam bentuk kesamaan melalui komunitas virtual. Artikel ini bertujuan untuk mendeskripsikan implikasi smart city terhadap munculnya komunalitas perkotaan. Padahal, komunitas urban dapat dibangun dalam mekanisme networked society yang diwujudkan dalam bentuk smart city oleh infrastruktur pemerintah.

THE HOAXES OF ILLEGAL FOREIGN WORKERS FROM CHINA: MORAL PANICS AND CULTURE OF FEAR

COMMODIFICATION OF PRIVACY AND PSEUDO-DEMOCRACY IN DIGITAL CULTURE

RADIO JOURNALISM IN DIGITAL ERA: TRANSFORMATION AND CHALLANGE

DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY AND ECONOMIC INEQUALITY IN INDONESIA

BEYOND PROSUMPTION: PROSUMPTION PRACTICE OF CONTENT WRITERS IN NEWS AGGREGATOR PLATFORM UC NEWS

PROBLEMATIC OF FEMININITY CONSTRUCTION IN VIRTUAL PUBLIC SPHERE

Keywords: Radio, technology, new media, journalism, traditional media, public opinion, spiral of silence DDC: 390.9. The expression of femininity caught in the social media such as WA Group. Previously the state played a significant role, which eventually fell according to the position of power in the state, now there are others, such as by HTI. The growing "new" definition of women's participation from HTI, happening in the virtual public sphere, contests the definition of gender and women's position in society.

The virtual public sphere shows new challenges in the women's movement that need to be thoroughly rethought.

RINGKASAN DISERTASI

REKOGNISI ADAT DALAM PENGEMBANGAN MERAUKE INTEGRATED FOOD AND ENERGY ESTATE DI PAPUA, INDONESIA

TINJAUAN BUKU

ISLAMISM AND THE POLITICS OF CITIZENSHIP IN INDONESIA

ADAT RECOGNITION IN MERAUKE INTEGRATED FOOD AND ENERGY ESTATE IN PAPUA, INDONESIA

INTRODUCTION

The project aimed to strengthen the national food and energy supply while accelerating economic development in the Merauke district (RvI, 2010). The Dutch colonial administration turned the Kumb sub-district in the Merauke district into an agricultural project area with the name Rijstproject Koembe. This project was quite successful and Kumb sub-district became the center of rice production in Merauke district (Koentjaraningrat & Bachtiar, 1963).

This project in Merauke is expected to attract investment not only in the rice farming sector but also in the plantation and forestry sector. The MP3EI was intended to accelerate the implementation of the MIFEE project to increase agricultural production. Such a policy should be implemented to attract large investments as the number of investments in Merauke district is important to support the development of the agricultural sector.

Merauke County needs to increase rice production and other agricultural production to meet national rice needs and achieve food security. The number of domestic investment projects in Merauke is 45 projects, with a total value of IDR 91.808 billion (USD 6.842 million), or about 25% of the total investment in Papua.

AIMS AND ARGUMENTS

In this section, I highlight in particular the establishment of the MIFEE project, which leads to adat land grabbing, in violation of the Special Autonomy Law, which prescribed adat land protection. Third, it aims to analyze the pitfalls of adat recognition in the implementation of the MIFEE project. It provides an explanation for the government's efforts to leverage Papuan recognition by admitting the adat institution in the Merauke district to facilitate the implementation of the MIFEE project.

It also examines the pitfalls of participatory mapping carried out by the adat community in Merauke district. And how Papuan recognition was used in the implementation of the MIFEE project. In the implementation of the MIFEE project, there are some forms of adata identity hijacking.

First, the hijacking of adat recognition is shown by the existence of the Customary Community Council as a government broker using adat. The result of the adat mapping makes clear who the owners of adat lands are.

ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

Papua's Special Autonomy Law mandated the formation of the Papuan People Assembly (Majelis Rakyat Papua, MRP) as cultural representatives and the Papuan People Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Papua, DPRP) as Papuan representatives, and stipulated that all members of these bodies must be Papuan. The slow process of the MRP's formation as a formal body to protect the Papuans can be seen as an example of the central government's concern to accommodate the bottom-up initiative. It can be used as a tool for recognition from the government's perspective, but on the other hand, it cannot solve the problem of misrecognition and the economic disadvantage of Papuans.

However, the government uses this map to pave the way for land scraping through the implementation of the MIFEE project, presenting it as recognition and respect for adat. Corrupt recognition is still recognition; however, the impact of recognition will differ from that of pure recognition. It can be used to analyze the formation of the adat institution called LMA in order to implement legal recognition.

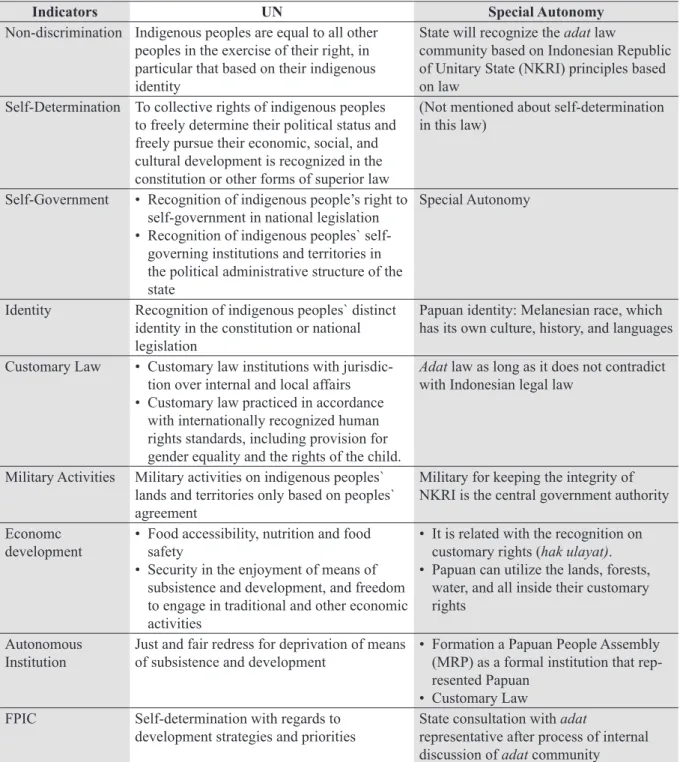

In the case of the MIFEE project, the LMA is supposed to represent the adat community in the negotiation process and protect the interests of the adat community. Using these indicators, it can be seen how much these aspects are adapted in the national legislation and other laws that regulate the existence of the adat community.

Land Grabbing

Corrupt recognition can be measured from the recognition policy initiative and/or the deviation from its implementation. For example, free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) is one indicator mentioned by the UN, which must be present to demonstrate that the state recognizes and respects the existence of the indigenous people. The legal and formal structure to protect the Papuans has been created, but the central government will try to obstruct the implementation of recognition, mandated by special autonomy laws, without stigmatizing, neglecting or oppressing the Papuans.

In this dissertation, I examine four cases in four villages—Duku, Sulu, Alu, and Muli1—that serve as examples of the process of land grabbing. Sulu represents a village that accepted company cultivation of their adat land in the early stages of MIFEE implementation, when John Gluba Gebze was still serving as Merauke district chief. The scope of the research is limited to the period between the implementation of the MIFEE project (2010) and the completion of Susilo Bambang Yudhono.

1 Due to the sensitivity of the issue, the names of the villages have been changed. Data were collected through interviews with leaders in each of the four villages, members of the adat community in each village, the former governor who started the MIFEE project, local government representatives, the company that has concessions in this area, and NGOs, who act as advocates on behalf of the adat communities in these villages.

DISSERTATION STRUCTURE

For the purpose of the MIFEE project analysis, land grabbing is defined as the control or possession of large areas of land for the purpose of converting them into agricultural properties by local and/or transnational companies with the involvement of local and central government through unfair procedures. harm the local livelihood. Duku represents a village that accepted company cultivation of their adat land after Romanus Mbaraka became the new head of Merauke district in 2011. Data collection was conducted in Merauke district in January, August and September 2014 and October and November of 2015.

The fifth chapter attempts to explain the pitfalls of adat recognition of the establishment of the Customary Community Council or new LMA in Merauke District called. It analyzes the new LMA position in the Marind Anim community after the establishment of the new LMA of Merauke District and the formation of LMAs in the sub-districts and villages. This section explains the relationship between the existence of the new LMA and the process of land grabbing in the MIFEE project.

The sixth chapter discusses the frontier of participatory mapping in four villages in the MIFEE project areas. This chapter concludes with a discussion of the negative effects, which are unintended consequences of participatory mapping, that can accelerate land grabs.

DISCUSSION

Recognition of indigenous peoples' self-governing institutions and territories in the political administrative structure of the state. 2018 the marginalization of Papuan not only in the economic sector but also in the political sector. Mostly, the new LMA acted as a security guard on behalf of the Indonesian government to check adat authority in the hands of the government.

Although it can be argued that the establishment of the new LMA is a form of recognition by the government of Papuan communities, this recognition is not based on the Papuan idea of adat as contained in Papua's Indicators as a Land of Peace (Jaringan Damai Papua 2014 ). Ultimately, this institutional recognition of adat is only artificial and has paved the way for government policies to enter Papua in collaboration with a small segment of the opportunistic Papuan elite. Unlike the participatory mapping in 1997, the recent participatory mapping aims to map the adat territories in the village.

This policy can also eradicate the negative image of the government neglecting the adat lands in the implementation of MIFEE. By bringing a new representative in the name of adat called the LMA, the central government has opened up invisible adat structures and expanded access to the resources within.

CONCLUSION

2018 With rather complicated adat structures of Papua, the government experienced difficulties in accepting the so-called representative demand of the Papuans to be accommodated. Therefore, it is necessary for the government to have a "representative" agency and the creation of "representative" body causes politics of brokers among the adat elite. Furthermore, spatial recognition was seen by the government as the way to escape from the Papuan's lingering mistrust of the government and from adat elites' competition over development program.

This is because Papua has the ability to describe their resources and capital on a legal basis. This legal narrative description is important for the Papuans to have an equal footing against government and corporate encroachment on their livelihoods. It increases the possibility for brokers to pave their way for asset appropriation by encompassing the authority of adat.

MIFEE di Luar Jangkauan Imajinasi Malind: Catatan Upaya Percepatan Pembangunan MIFEE di Wilayah Merauke Papua.