First, I analyze how trade monopsony and institutions of forced labor reduced Africa's gains from trade during the colonial period. 86 4.3 Colonial agricultural production, price gaps and current developments 89 4.4 Rural underdevelopment or lower urbanization: a large margin.

Introduction

Introduction

Moreover, the level of extraction varied considerably across different colonies and economic activities and decreased in the second half of the colonial period. Second, I use newly collected data on labor institutions to disentangle the effect of restrictive labor institutions on producer prices from the effect of monopsony.

Historical Background

Free peasant production was used in most cases, accounting for almost 60% of the total value of exports. At the beginning of independence, free peasant production accounted for almost 70% of the total value of exports, while the rest was produced under concessions.

A Model of Colonial Extraction

Because both Q(pA) and Q0(pA) are positive, the price for Africans under monopsony is lower than under competition. The price under monopsony and forced labor institutions is therefore lower than the price under simple monopsony.

Result 1: Prices to Africans and Competitive PricesPrices

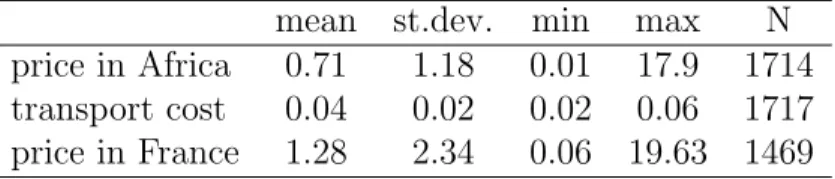

- Data

- Empirical Strategy

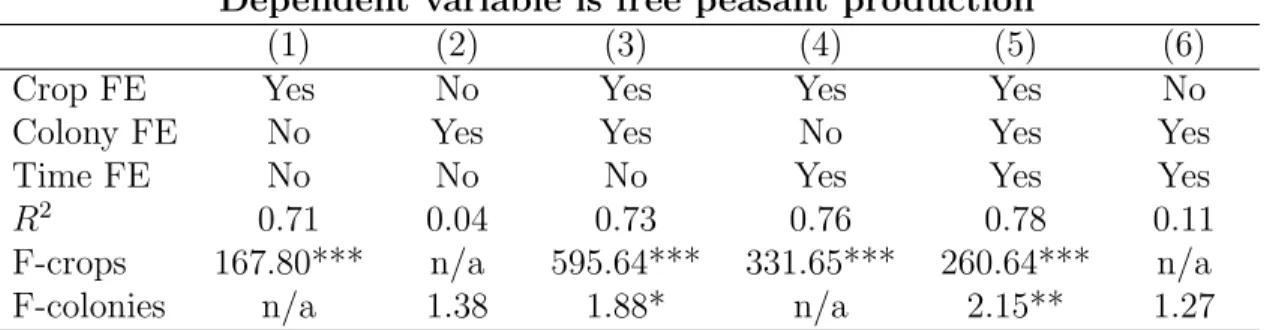

- Results

Nevertheless, given the importance of the French market, using export prices in France is a good approximation. First, including fixed effects does not increase R2 by much: omitted costs are not a large factor in the price in Africa.

Result 2: Labor Institutions and Prices to Africans

For example, Coquery-Vidrovitch (1972) wrote about rubber quotas in the Congo in the 1910s, while Suret-Canale (1971) analyzed free peasant peanut production in Senegal. Over time, we observe a decrease in the level of coercion and an increase in the scope of free agricultural production. We expect β1 <0: prices should be lower under compulsory farm production than under free farm production.

Column (1) reports the result of the probit model regressing the free farm production dummy on the elasticity of supply.

Result 3: Colonial Extraction and Gains from TradeTrade

Based on these results, I can now wonder to what extent monopsies and forced labor institutions have reduced African profits from trade. To disentangle the effects of forced labor institutions from those of monopsony, note that area 1 of Figure 2.4 represents the loss of trade profits due to monopsony, while areas 2, 3, and 4 represent the loss due to forced labor institutions. Disentangling the effects of monopsony and forced labor institutions, I estimate that the upper bound on the share of losses due to monopsony was on average (over all compulsory production observations) 37%.

Thus, when forced labor institutions were used, they accounted for at least 63% of the losses in gains from trade.

Conclusion

Appendix

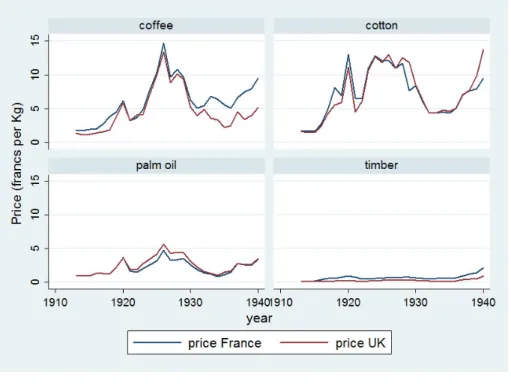

- Prices in France and World Market Prices

- Post-Independence Prices

- Data Sources

- Appendix Figures and Tables

In this section I examine preliminary data on prices in Africa and France after independence. The price in Africa is the average of the prices of all former colonies that produce that product. The price difference between Africa and France was small immediately after independence, but, with the exception of cotton, has been increasing since the 1970s.

33 The price in Africa is the average price of all cotton-producing colonies, excluding the five years for which the price in Africa was higher than the price in France.

Introduction

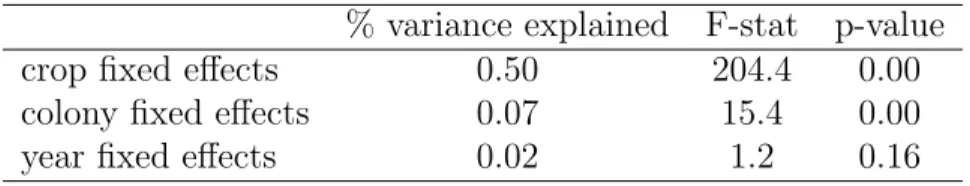

In this chapter I provide evidence that the type of crops is more important than the location of the colony for the choice of institutions. I then show that simple fixed effects on crops account for much of the variance in institutions, while the explanatory power of fixed effects on colonies or settler mortality is much lower. Nevertheless, even if crop fixed effects account for a large portion of the variance, they cannot really “explain” institutions.

In the second part of the chapter, I focus on this problem by trying to understand what lies behind the crop fixed effects.

Historical Background and Data

As described in more detail in chapter 2, I first identify the main crops that were exported to each colony in each of the five decades, using data from various colonial statistical publications. It includes all agricultural activities whose export value constitutes at least 1% of the total value of exports from the respective federation. Since poll taxes had the function of generating labor and raising revenue for the government and were used in all colonies, I exclude them from the present analysis.5.

However, the coverage is satisfactory: the activities in the dataset represent 80% of the value of all exports from West and Equatorial Africa over the entire period.

Crops or Locations?

- Preliminary Analysis

- Empirical Analysis

Free peasant production and contract labor are more dispersed in West Africa, while compulsory production is more dispersed in Equatorial Africa. According to the number of cases, the trend is an increase in free agricultural production and a decrease in the share of contractual and compulsory production. A different picture emerges when observing the value of exports: the share of free agricultural production remains unchanged, contract work is increasing, and compulsory production is decreasing.

Crop fixed effects explain less of the variance (51%), but the main results are qualitatively similar.

What is Behind Crop Fixed Effects?

- Theoretical Framework

- Testable Implications and Evidence

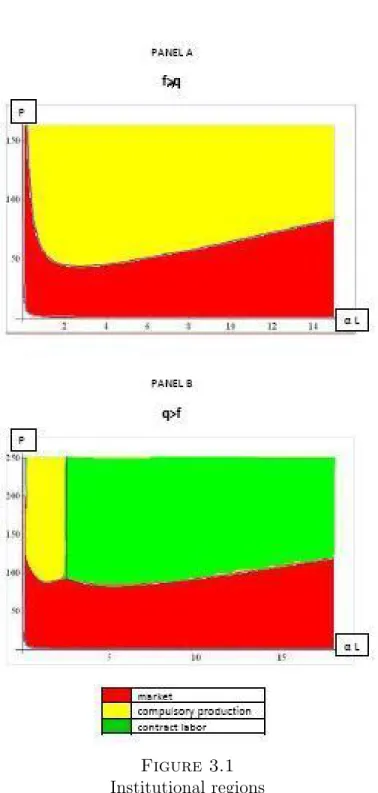

The profit from free peasant production is higher than the profit from contract labor if p <. The profit of contract labor is higher than the profit of forced production when q > f and αL > Fq−f−Q. The profit of forced production is higher than the profit of contract labor whenq < f or whenq > f andαL < F−Qq−f.

Thus, an increase in price increases the colonizer's income more under indentured labor/forced production than under free peasant production.

Conclusion

As expected, the quantity coefficient is positive and significant: a larger production scale is associated with more contract labor and less compulsory cultivation. However, the quantity coefficient becomes insignificant when we control for the type of crops (column 4). In general, prices seem to be important in determining the choice between market and non-market institutions, while the scale of production has explanatory power for the choice between compulsory production and contract labor.

To interpret these findings, I develop and test a theoretical model, which links the choice of labor arrangements to differences in price of crops, costs of institutions and scale of production.

Appendix

- Definition and Sources

- Appendix Figures and Tables

In this chapter, I contribute to this literature by focusing on the determinants of labor institutions in the French colonies. Using a labor institution dataset, I find that the relationship between colonies and institutions is much weaker than expected. On the other hand, I show that there is a strong correlation between labor institutions and crop types, and that this relationship accounts for most of the variation in labor arrangements.

This evidence suggests that factors related to crops, such as prices, are more likely to explain labor institutions than factors related to colonies, such as settler mortality.

Introduction

I show that price gaps are strongly negatively correlated with current development, as shown by brightness data from satellite images (Michalopoulos and Papaioannou, 2013). Moreover, the correlation is strong for the inclusion of country fixed effects: colonial price gaps account for differences in development both across and within countries. I then examine the channels that mediate the relationship between colonial price gaps and current economic development, looking at brightness in urban and rural areas.

I show that price gaps are negatively correlated with the size of urban areas and level of development in rural areas.

Historical Background and Data

- Price Gaps

- Luminosity

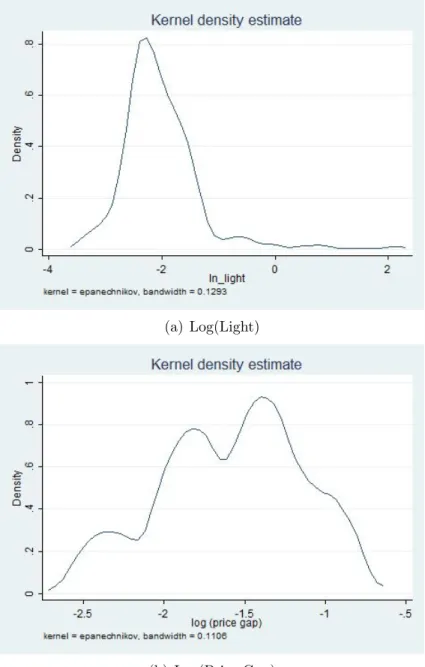

A crop is considered to have been produced in the pixel if colonial records show that production in the colony in which the pixel is located is not zero and if the land transportation costs from the pixel district to the port are less than the reported price at the port. Second, I calculate a price difference at the pixel level, by averaging the differences between crops and pixels, weighted by the per hectare value of each crop (price to the African producer times productivity) in the given pixel. As a measure of local economic development, I use brightness data from satellite images of the nighttime world.

The data comes from the Earth Observation Group of the NOAA National Geophysical Data Center (2013), which reports the intensity of light radiation at a resolution of 15 arcseconds (about 500 square meters) for the entire globe.

Colonial Price Gaps and Current Development

I use log files to reduce the impact of observations of extreme values and to interpret regression coefficients more directly as elasticities.4 The top panel shows the relationship within the full sample: the presence of a negative correlation is clear. In this case, the price gap coefficient measures the relationship between price gap and brightness within countries. In column (1) of Table 4.3, I output the log (price gap) based on the log of the potential value of agricultural production in the 1950s.

In columns (3) to (6), I directly estimate the relationship between price gaps and lights, including colonial agricultural production as a control variable.

Channels of Causality: Effects on Rural and Urban AreasUrban Areas

In columns (5) to (8), I regress the share of illuminated pixels below the top percentile, which measures the size of inhabited rural areas, on price gaps. Price gaps are positively related to urban development, as is associated with average brightness in urban areas. Price gaps are associated with less developed rural areas but have no effect on their size.

Despite the negative overall effect, price differences are still positively related to brightness in the top percentile.

Conclusion

They are particularly related to a decline in the number/size of cities and a decline in development in rural areas. Nevertheless, they are correlated with higher development in urban areas, increasing urban-rural inequality. By looking at brightness in urban and rural areas, I suggest that colonial withdrawal affected subsequent growth by reducing both urbanization and development in rural areas.

Nevertheless, the overall impact on development is negative and the differential effects in rural and urban areas may in fact be the reason why trade monopsony and extractive institutions persisted long after independence.

Appendix

- Definitions and Sources

- Appendix Figures and Tables

The linear distance in km from the center of each administrative district to the nearest port, calculated by GIS. For each pixel and crop, I estimate the potential value as the product of the price in France, net of marketing costs, times productivity per hectare times cultivated land area. The figure reports the scatterplot and linear fit for the regression of the country means of log(light) and log(price gap).

Panels A and B report the log kernel density of the mean brightness, excluding pixels above and below the top percentile, respectively.

Conclusion

Are these incentives influenced by local factors, such as the type of political support (urban or rural) the independent government has received? Or are they shaped by international factors, such as trade relations between Africa and the rest of the world. Finally, the higher population density of the British colonies allowed the colonizer to implement various coercive institutions, such as land alienation, to acquire the African labor force.

Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World's Income Distribution.