Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie;. Loss of manipulation and presentation capabilities 48 Weak links in the documentation chain and loss of.

Preface

A senior member of the executive committee could claim after a study visit to the national libraries in 2002 that "The National Library of Australia remains at the forefront of digital archiving and preservation activities among national libraries" (Gatenby, 2002b). From the National Archives of Australia came theoretical and conceptual developments that helped to think about digital archiving.

What is Preservation in the Digital Age? Changing

Preservation Paradigms

Introduction

The old terms do not always provide useful meanings in the digital environment and can actually be misleading and sometimes harmful. The term benign neglect provides an example of a concept that is useful in the pre-digital preservation paradigm but harmful in the new one.

Changing paradigms

There has also been a change in the ways in which information is produced and made available to its community of users. If the creator is now also the publisher and distributor, as is often the case in the digital world, who has the responsibility of securing (receiving information).

The need for a new preservation paradigm

Definitions associated with the old storage paradigm are firmly rooted in the storage of objects—physical objects that carry information content. Discontinuities in the management of a digital collection will mean that there is no collection left to manage.

Changing definitions

Cloonan suggests part of the answer - 'the preservation of knowledge, not the preservation of individual items' - but there is much more. Choice (selection of material to preserve) is no longer a decision made later in the life cycle of an item, but for digital material has become an ongoing process intimately connected to the active use of the digital files'.

Preservation definitions in the digital world

One is that for digital materials, “their preservation should be an integral part of the original design of systems and. These issues and concepts are addressed in two of the most comprehensive recent publications on digital preservation, the influential Preservation Management of Digital Materials: A Handbook (Jones and Beagrie, 2001) and the UNESCO Guidelines for the Preservation of Digital Heritage (UNESCO, 2003). ).

What exactly are we trying to preserve?

The definitions are also very specific regarding the need to preserve other properties of digital materials. To ensure that digital material remains useful in the future, access to it is needed – and not just access, but access to “all the attributes of authenticity, accuracy and functionality” (Jones and Beagrie, 2001, p. 9).

How long are we preserving them for?

In addition to the bitstream, which is usually "not comprehensible or reproducible" by itself, "all the information and tools that would be necessary to access and understand" the digital material must also be preserved (UNESCO, 2003, p.40). The essential elements (or important properties) of digital materials, taken together, allow us to re-present the materials in the way they were originally intended; i.e. to preserve them.

What strategies and actions do we need to apply when we preserve them?

Such definitions provide useful ways of thinking about digital preservation programs: for example, for resource allocation, the long-term resource implications of initiating long-term preservation are ongoing and therefore large.

Conclusion

Why do we Preserve?

Who Should do it?

Why preserve digital materials?

If there is a legal obligation to keep it (NSF-DELOS Working Group on Digital Archiving and Preservation, 2003, p.3). And why?” (NSF-DELOS Working Group on Digital Archiving and Preservation, 2003, p.2) – and the growing number of stakeholders in the digital age means that different interests have to be taken into account.

Professional imperatives

First, he has to take every possible precaution to protect his archives and for their safekeeping. In the case of archives, these reasons are often linked to administrative and political accountability.

Other stakeholders

A useful illustration of the major changes that will be required is the management of personal correspondence. The case of Australia illustrates some of the issues and difficulties in finding viable solutions.

The extent of the preservation problem

Although the evidence allows only general statements, it is commonly believed that paper brittleness affects on the order of 30 percent of the collections of major research libraries in the United States. Some of the documented examples are about data recovery, in the sense that data thought to have become inaccessible could be recovered, or thought to have been lost, only misplaced.

How much data have we lost?

An attempt to answer these questions is especially valid in the context of the history of documentary heritage conservation. The most cited, and even overused, examples are those cited in the 1996 report of the Task Force on Archiving of Digital Information.

Current state of awareness of the digital preservation problem

Staff at U.S. college and research libraries are aware of the problems in general terms, but lack specific knowledge about how to address them. Our current ability to do this is hampered by the widespread lack of awareness of the problem.

Why There’s a Problem

Digital Artifacts and Digital Objects

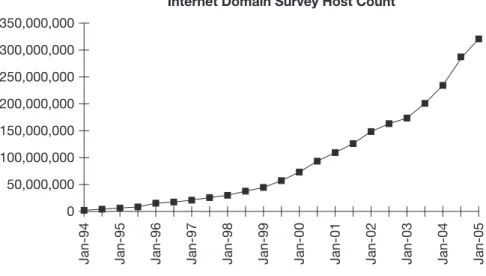

Current trends in information management and delivery call for effective preservation of digital materials. The sheer number of digital materials now in existence is in danger of becoming overwhelming and the rate at which they are created is increasing (as noted in Chapter 1).

Modes of digital death

Fifteen of the 36 institutions that responded to the survey could not access some of the digital materials they held because they lacked the 'operational and/or technical capacity to assemble, read and access' them. Digital materials may be well protected but so poorly identified and described that potential users cannot find them.

Digital artifacts

Similarly, improper handling of digital objects can result in physical contact with the part of the media that records the data. The following examples of magnetic tape and optical discs illustrate many of the factors that contribute to the deterioration of digital objects.

Magnetic media

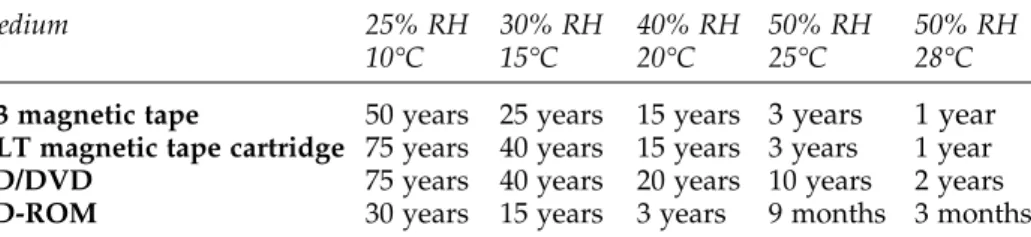

This point is explored in a 2001 report by the Working Group on Artifacts in Library Collections. Figure 3.3 shows the life expectancy of some common data tapes.

Optical disks

As noted in the section on magnetic tape, there is a clear relationship between the manufacturing quality of optical discs and their longevity. When using optical discs in a preservation environment – for intermediate archival use, not long-term storage – it is essential to check the quality of new discs before use.

A future for digital artifacts?

This is not the case: all digital artifacts must be handled with care and optical discs are no exception. While it is widely recognized that aging of equipment and software, rather than the lifespan of digital artifacts, is the limiting factor, it is worth devoting research and resources to improving digital artifacts.

Digital objects – more than digital artifacts

Loss of functionality of access devices

It's probably quite lucky as the 'F' key doesn't work and most of the letters on the keyboard have been scratched off by excessive use. The understanding of the general public (as presented by journalists) about digital preservation still has a long way to go.

Loss of manipulation and presentation capabilities

The State Library Foundation has purchased the notebook as part of a package of Carey papers that effectively tells the inside story of the creation of [the novel] True History of the Kelly Band. The information professions have little or no control over this rapid technological obsolescence, which is driven by the ever-changing financial demands of the information technology market.

Weak links in the documentation chain and loss of contextual information

Many of the concepts applied to ensure the authenticity and integrity of preserved digital objects come from research and thinking within the recordkeeping community, such as the results of the Functional Requirements for Evidence in Recordkeeping Project at the University of Pittsburgh, and InterPARES ( see chapter 5). Gavan McCarthy, director of the Australian Science and Technology Heritage Center at the University of Melbourne, gives another example: that of databases produced by Australia's State Electricity of Victoria.

Selection for Preservation – The Critical Decision

The digital mortgage resulting from the selection decisions should also be considered: ‘Program costs do not stop when the website disappears’ (Vogt-O’Connor, 2000). It considers additional factors to consider to develop effective selection policies and practices for digital materials, such as the role of intellectual property, the importance of preserving context and the place of stakeholder input.

Selection for preservation, cultural heritage, and professional practice

This has been challenged by the "new humanities and social sciences", which increasingly demand that libraries collect more "of what was previously dismissed as ephemeral and 'popular'". The third is that selection decisions are based on the type of material, but Burrows suggests that this scenario raises more questions than it answers: “is it more important to preserve websites than Usenet posts?” The fourth is that we select based on the most at risk . material (Burrows, 2000, p.148).

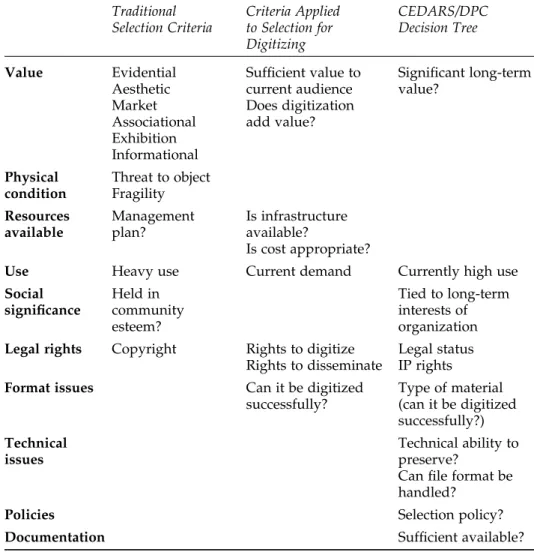

Selection criteria traditionally used by libraries

The characteristics of artefacts addressed by these criteria are age, evidential value, aesthetic value, scarcity, associational value, market value and exhibition value (Working Group on Artifacts in Library Collections, 2001, pp. 9,11). Libraries have not always got this right – in fact, it is impossible to get it right, given “the context of changing perceptions of value and the fluid dynamics of intellectual inquiry” (Task Force on the Artifact in Library Collections, 2001, p.5).

Appraisal criteria traditionally used by archives

By linking the administrative, evidential and informative value of data to an organization, it clearly suggests the aspect of context: the context - the organization - is defined. The ISO Standard Records Management – Guidelines, which is based on an earlier Australian Standard for Records Management, does not define assessment, but notes that capture is "the process of determining that a record should be made and maintained".

Why traditional selection criteria do not apply to digital materials

A third difference is the requirement that informed preservation decisions about digital materials be made early in their existence. Another issue is the difficulty in determining ownership of intellectual property rights for some digital materials.

IPR, context, stakeholders, and the continuum approach

More differences between digital and non-digital materials that should be considered when developing selection criteria are listed in the UNESCO Guidelines (UNESCO, 2003, p. 74). Any effective process and criteria for selecting digital materials for preservation must take these differences into account.

Intellectual property rights and legal deposit

Legal deposit legislation

Legal deposit legislation for digital materials is often considered an important step in a viable national preservation program for digital materials. But these are more time-consuming and resource-intensive arrangements and the National Library of Australia is keen to see legal deposit legislation for digital materials introduced in Australia so that it can more effectively fulfill its role in preserving Australia's documentary heritage.

Context and community

For others, it will be necessary to preserve enough contextual information to enable search or manipulation of the digital material. Selection criteria for determining which digital materials to preserve must take this contextual information into account.

Stakeholder input

For other communities, there must be enough contextual information of the right kind to demonstrate that the authenticity of the digital materials has not been compromised. Increased involvement from some sectors of society in the selection of digital materials for preservation is also expected.

Value of the continuum approach

A similar idea is "community authority", a concept Janes uses in relation to website authority. Janes gives the example of the Internet Movie Database (www.imdb.com), which requires errors and omissions to be reported to the IMDB database managers, who will check and incorporate as appropriate.

Developing selection frameworks for preserving digital materials

The Cedars Project Team report contains one of two particularly useful statements about the selection of digital materials for preservation (Cedars Project Team, 2002). It suggests that selection decisions for digital preservation should 'be pragmatic' and be based on 'estimated value of the material, the costs of storage and support mechanisms and the production of metadata to support the material' (Cedars Project Team, 2002, p. 53).

Towards a new decision-making framework

As already mentioned, increasingly non-traditional criteria, such as the legal and intellectual property rights that govern a resource, whether we have the technical ability to preserve it, the costs involved in preserving it, and the presence of documentation and meta appropriate data, are being made. at the center of decision-making in the selection of digital materials for preservation. UNESCO guidelines consider attributes that contribute to authenticity as "elements that give the material its value".

How much to select?

While it is fairly straightforward to define the criteria that libraries traditionally use when selecting for preservation and describe the practice of evaluating archival materials, they cannot be directly applied to the selection of digital materials for preservation. Further research is needed on selection, as on other parts of the digital materials life cycle.

What Attributes of Digital Materials Do We Preserve?

We need to better understand the nature of the changes we need to make to preserve digital materials. Another concept we need to know more about when addressing the question "what attributes of digital materials do we store?" is that of acceptable loss.

Digital materials, technology and data

Current knowledge of the characteristics of digital materials and their importance to users is insufficient to effectively preserve digital materials. This difference can be so extreme that the authenticity of the digital object is questioned (Digital Preservation Testbed, 2003, pp.13-14). These concepts are expanded considerably in the consideration of digital objects as physical, logical or conceptual objects in Chapter 1.).

The importance of preserving context

In other words, we need to preserve information about the context of the data (this is also stated in Chapter 4). In order for records (that is, records in the context of record keeping, records as evidence of transactions) to be authentic,.

The OAIS reference model

The resulting package is considered discoverable based on the Descriptive Information (Consultative Committee for Space Data Systems, 2002, p.2–5). This information – metadata – is an essential part of the OAIS reference model and is increasingly seen as essential to all digital preservation activities.

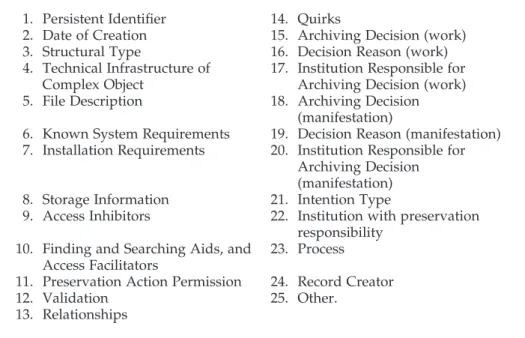

The role of metadata

Early preservation metadata schemes were developed by NEDLIB and CEDARS, and the National Library of Australia. Knight describes the progress and expectations of the National Library of New Zealand's metadata schedule for preservation (Knight, 2003, p.18).

Persistent identifiers

The NSF-DELOS Working Group on Digital Archiving and Preservation notes that "there has been limited assessment of the effectiveness or cost of metadata for managing digital entities over time" and suggests that research is needed, for example, to demonstrate their value for specific purposes and for specific, how much metadata you need. Tools are needed to "assist in the creation, authoring and management of metadata", such as those that automate or partially automate the creation of metadata; these are being developed, an example being the National Library of New Zealand metadata retrieval tool.

Authenticity

According to Casson (2002), "the actors in them took liberties with the text" to the extent that Lycurgus (leader of Athens from 338 to 325 BC) directed it. For museum objects, the provenance (‘the chain of ownership and context of use of an object’ ((Significance), 2001, p.37) is particularly important.

Significant properties

It is described in the UNESCO Guidelines. The idea is simple; the application of the same software and hardware to the same digital materials must create a. For example, would advertising banners be considered an essential part of the look of the material.

Research into authenticity

He identifies five aspects of "preservation quality"—readability, understandability, appearance, functionality, and "look and feel"—and gives examples of how these can be applied to a variety of digital objects commonly encountered on the Web (Clausen, 2004, p .8–10). According to the NSF-DELOS Working Group on Digital Archiving and Preservation, the digital preservation research agenda includes research into tools that allow future users of digital materials to determine whether they are authentic (NSF-DELOS Working Group on Digital Archiving and Preservation , 2003, p.vii).

Functional Requirements for Evidence in Recordkeeping Project (Pittsburgh)

The custodian of records must assess the authenticity of the documents before they are transferred to the custodian. Specific rules for document authentication (i.e. which documents are authenticated, by whom and how).

Trusted digital repositories

Thorough documentation of the entire process of preservation is also recommended (US-InterPARES Project, 2002, pp.9–10). The authenticity of digital material must be defined in relation to users' requirements, and the elements of the material that meet these requirements must also be clearly defined.

Overview of Digital Preservation Strategies

Practices include technology – the 'machinery and equipment based on the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes' (as defined in the Concise Oxford English Dictionary). The UNESCO guidelines identify some strategies that are likely to be viable in the long term: 'the use of standards for data encoding, structuring and description', emulation and migration of data (UNESCO, 2003, pp.124–125) .

Historical overview

There still seems to be a mindset that will encourage us to develop the killer application, a single technical solution (such as Rothenberg's championing of emulation, described below), although this way of thinking has weakened. Two key realizations have allowed us to move towards a new conservation paradigm and develop new approaches, strategies and practices.

Who is doing what?

A study of digital preservation practice in 21 internationally operating natural and science publishing organizations concluded that. This makes the experience of those who have applied digital preservation strategies and technologies in more than one test situation even more important.

The Australian experience

Although there was relatively little comment in these interviews about the technical issues that need to be considered in effective digital archiving strategies, it was noted that it is important not to rely on proprietary data formats or systems. The context in which digital archiving operates, and thus the strategy, must be clearly understood.

Criteria for effective strategies and practices

Experience Is there already verifiable experience of using the technology for the preservation of similar objects. Reliability Does the technology work reliably and the reliability of the result can be easily checked.

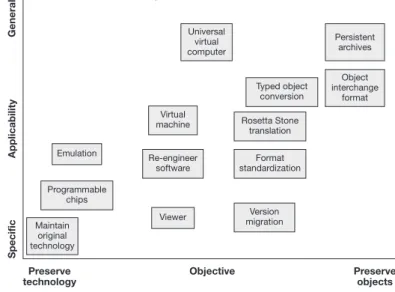

Typologies of principles, strategies and practices

On the 'preservation technology' side of the spectrum, methods that seek to hold data in specific logical or physical formats and to use technology originally associated with those formats to access the data and reproduce the objects. On the 'preserving objects' side of the spectrum, methods that focus on preserving essential characteristics of objects that are defined explicitly and independently of specific hardware or software (Thibodeau, 2002).

A typology of digital preservation?

Principles (general ways of thinking, usually at the conceptual level) a) Separate archival storage of bits from the processes of representing and

Lavoie and Dempsey have noted that digital preservation is "an agreed-upon set of outcomes" based on considerations such as the complexity of digital materials and the features we collectively decide should be preserved. They describe specific principles, strategies and practices: Chapter 7 examines approaches based on technology preservation and Chapter 8 examines approaches based on digital object preservation.

Preserve Technology’ Approaches

Tried and Tested Methods

But, as Jones and Beagrie point out, these strategies and practices do not address the real problems of technological obsolescence; they only postpone the need to make decisions. This chapter draws heavily on two main sources: Preservation Management of Digital Materials: A Handbook by Maggie Jones and Neil Beagrie (2001), and the UNESCO Guidelines for the Preservation of Digital Heritage (2003).

Non-solutions’

Proposing them as anything more than a temporary solution is a classic example of the inappropriate application of pre-digital paradigm preservation thinking to digital materials. This approach, too, is an example of the inappropriate application of predigital paradigm preservation thinking to digital materials.

Do nothing

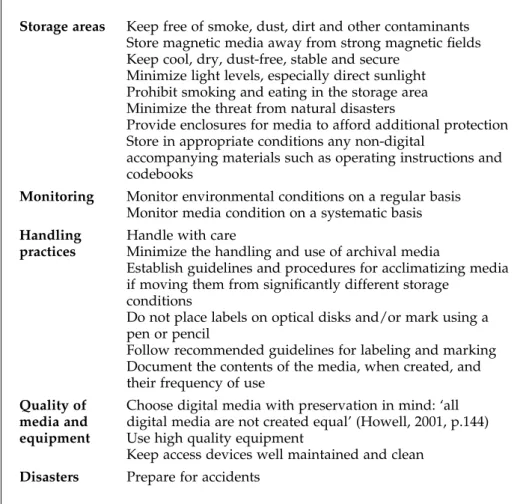

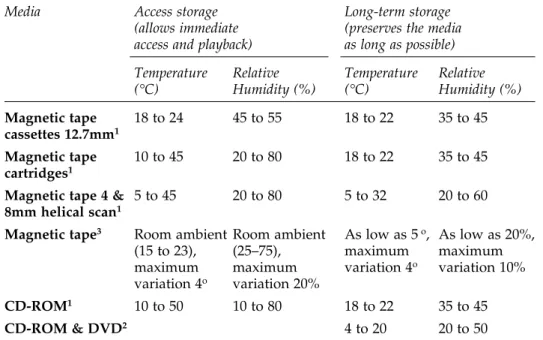

Storage and handling practices

Another factor for media in long-term storage is the need to allow the media to acclimate when removed from this storage to room temperature for access (playback) purposes. Long-term storage areas are usually kept at much lower temperatures and relative humidity levels: For example, Byers' "consensus from several reliable sources on the prudent care of CDs and DVDs" (2003, p.1) recommends long-term storage at storage levels such as 18oC and 40 % RH, but 'a lower temperature and RH.

Durable/persistent digital media

Despite the limited use of these strategies and practices aimed at increasing the longevity and effectiveness of digital media, they are useful tools. We should also bear in mind that there is still a significant lack of awareness of the real problems of digital preservation.

Analogue backups

We must bear in mind that reliance on strategies and practices that focus on media preservation have "the potential to compromise content by providing a false sense of security" (Kenney et al., 2003). As noted in Chapter 2, "the myth that long-lived media equals long-term storage is still disturbingly popular."

Policy development

The original digital objects should, where possible, be preserved to allow access mechanisms to become available in the future (UNESCO, 2003, p.147). It is possible that the preservation of analogue formats in archival conditions for long periods of time may not be feasible for technical and/or financial reasons, so these factors should be taken into account.

Standards

UNESCO's guidelines add that using widely available standards 'is more likely to allow reinterpretation of data or reconstruction of tools in the future, if necessary', but notes that using standards is an 'investment' strategy , that is, it involves investing effort early in the process (UNESCO, 2003, pp.127–128) so it has resource implications. Rothenberg offers a word of caution: 'standards are not sufficient' and 'are not realistic in the foreseeable future' because 'using successive and evolving standards would require translation, but translation between standards is rarely reversible without loss. , so this cannot reconstruct an original artefact' (Rothenberg, 2003).

Digital archaeology

Other benefits that standardization would bring are cost reductions because there are fewer and less complex variations to deal with: for example, economies of scale can be achieved when migrating data (Jones and Beagrie, 2001, p.107). .

Preserve technology’ approaches

Strategies and practices at the extremes of the 'keep technology' end of the spectrum ideally allow no change at all. Of the two approaches noted in this 'preserve technology' category, one - emulation - is generally considered viable for long-term preservation, but the other - retain original technology - is not.

Technology preservation

Authenticity is preserved, both by the digital materials (which are unaltered) and by the technology and software platforms that reproduce them (which are also unaltered). To work effectively, this 'conserve technology' approach has specific requirements, which are formulated in UNESCO guidelines.

Technology watch

It requires the hardware and software that will be required to provide access to be actively identified and monitored as they move towards obsolescence (discussed in When a survey of digital material in the collections of the State Library of Victoria was carried out in 2003, it was initially assumed that so that the library catalog could serve to identify relevant material.

Emulation

In their opinion, emulation has good possibilities for preserving complex digital materials (Jones and Beagrie, 2001, p.105). Emulation is unlikely to be the 'magic bullet' (Lynch, 2004), the only solution for digital preservation, as it is sometimes promoted.

The Universal Virtual Computer

Of the range of strategies and practices mentioned here, some are interim measures and only one – tracing – is generally considered viable for the long-term preservation of digital material. The next chapter considers a range of approaches from the other end of the conservation spectrum: 'preserving objects'.

Preserve Objects’ Approaches

New Frontiers?

VERS (Victorian Electronic Records Strategy) is the subject of Case Study 4, and illustrates the subject of encapsulation.

Preserve Objects’ approaches

Some of the strategies mentioned in this chapter are investment strategies, in terms of the classification of digital preservation strategies in the UNESCO guidelines (UNESCO, 2003, pp.126-149); it is mainly about ‘effort at the beginning’. Other strategies mentioned in this chapter (backward compatibility and version migration and migration) are short-term strategies, strategies that "probably work best in the short term."

Bit-stream copying, refreshing, and replication

Two of the strategies and practices included in this chapter are classified as “current leaders as long-term strategies” and have been shown to work in the short term (UNESCO, 2003, pp.124-126).

Bit-stream copying

Refreshing

It is usually performed to copy data "from one long-term storage medium to another medium of the same type" (Kenney et al., 2003), for example, from a DAT tape that becomes unstable to a new DAT tape. As with bitstream copying, refresh is a necessary part of any successful digital preservation program, but it does not address obsolescence issues (Kenney et al., 2003).

Replication

At intervals, appliances [the name given to the personal computers with LOCKSS software] participate in polls and vote on the digestion of some of the content they have in common. In November 2004, the LOCKSS project announced that it has successfully demonstrated 'transparent format migration of preserved web content' (Rosenthal et al., 2005).

Standard data formats

Another example that illustrates the range of standards and file formats that must be handled in everyday use comes from a proposal for a DOMS (Digital Objects Management System) at an Australian university:. Four main responses to the issues presented by the proliferation and complexity of file formats can be identified: file format registries, standardization of file formats, limitation of the range of file formats handled in digital storage systems, and development of file formats. archive files such as PDF/A.

File format registries

Their study concluded that information about publicly available file formats is vulnerable because it depends on the efforts of interested individuals. Other file format registries used to support digital preservation include Wotsit's Format: The Programmer's Resource (www.wotsit.org) and My File Formats (www.myfileformats.com).

Standardizing file formats

Format standardization is appropriate for situations where the file formats can accommodate all or most of the features of the digital material. One benefit of the strategy of selecting and applying standard file formats is that it likely slows down the rate at which file formats become obsolete.

Restricting the range of file formats

This strategy is most appropriate when the digital archive is responsible for digital materials that are uniform in structure and content. Using stable and open file formats has the same advantages as mentioned in the previous section.

Developing archival file formats

XML is specifically designed to be used regardless of hardware platform and is supported by many open software applications. However, since such records are a very large part of the digital materials type in some contexts, such as archival environments, this approach is likely to be fruitful.

Migration

Minimal storage – storing a copy of the bitstream (denoted in this chapter as bitstream copy and refresh). Keeping copies of the original material if some essential elements may be lost during the migration.

Viewers and migration on request

Encapsulation

However, some skepticism is evident in the statement that “the grouping process appears to reduce the likelihood that any critical component needed to decode and render a digital object will be lost” (Kenney et al., 2003). The risk of missing vital information in the specification appears to invalidate this approach (University of Leeds, 2003, p.39).

Digital mass storage systems

A digital mass storage system can be simple or very complex, depending on what is required of it. In addition to the technical requirements, digital mass storage systems require well-defined management processes, including.

Conclusion: combining principles, strategies and practices

The secure server is located in a "state-of-the-art data center facility" with comprehensive security features such as a fire suppression system, backup power, environmental control, monitoring, and "full system redundancy [Redundant IBM RAID 5 servers], including Tier One redundant network connections providers (Global Data Vault Inc., 2005).

Digital Preservation Initiatives and Collaborations

Collaboration

The reasons for the prominence of collaborative action on digital preservation can largely be found in the scale of the problems and the uncertainty of how to tackle them. Morris sees promise in "the way organizations from different parts of the information chain are beginning to work together to address some of the problems" (Morris, 2002, p.130), but cautions against this.

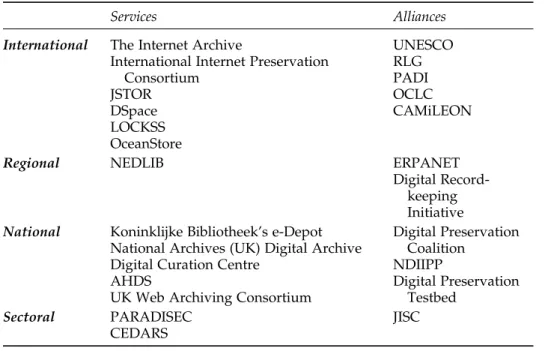

Typologies of digital preservation initiatives

Despite its imperfections, this typology applies because it accommodates most current digital preservation activities. Among other useful lists of digital preservation activities is the Directory of Repositories and Digital Preservation Services in the UK (Simpson, 2004b).

International initiatives and collaborations

International services

Its website (January 4, 2005) describes its goals as "working to prevent the Internet—a new medium of great historical significance—and other 'born digital' materials from fading into the past" and promoting the ideals of "open and free access to literature and other writings that have long been considered essential to the education and maintenance of an open society.The Internet Archive is funded by donations from individuals and philanthropic organizations (including the Hewlett Foundation, the Sloan Foundation, the Kahle/Austin Foundation, and the National Science Foundation) and by contract work for bodies such as the Library of Congress, the National Archives of the United States and Britain, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France The Internet Archive has influenced digital preservation by demonstrating that large amounts of online material can be archived over time.

International alliances

In conjunction with the Charter on the Preservation of the Digital Heritage, UNESCO has contracted the National Library of Australia to develop guidelines for digital preservation. Perhaps the most influential digital preservation activity is the participation, with the Commission on Preservation and Access, in the Task Force on the Archiving of Digital Information.

Regional initiatives and collaborations

Regional services

Regional alliances

His thematic workshops and seminars have covered a wide range of topics, for example OAIS, digital preservation policies, Internet archiving, metadata, scientific data evaluation, archive file formats and persistent identifiers. These case studies have led to the realization that most organizations 'are hesitant in their digital preservation activities', often due to a lack of awareness, and yes.

National initiatives and collaborations

National services

It is important to note that the Digital Curation Center will not act as a data repository. The activities of the Digital Curation Center will be followed with great interest worldwide.

National alliances

The DPC sponsors a Digital Conservation Award as part of the Pilgrim Trust Conservation Awards. The importance of the DPC for digital preservation lies in its active encouragement of digital preservation through its lobbying and promotional activities.

Sectoral initiatives and collaborations

Based at the National Archives, it researched the digital preservation techniques of migration, emulation and XML and applied them to a range of digital materials such as text documents, spreadsheets, e-mail messages and databases. This part is based on Beagrie (2003, p.28) and information available on the website of the National Archives (www.digitaluuraliteit.nl/home.cfm)).

Sectoral services

The goal was to advise others in the industry on digital preservation best practices. It has vigorously pursued digital preservation activities through partnerships such as the AHDS, CEDARS, and CAMiLEON (all of which are mentioned elsewhere in this chapter).

Challenges for the Future of Digital Preservation

What have we learned so far?