SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

Bureau ofAmerican EthnologyBuUetin 191

Anthropological Papers,

No.

73THE ARCHEOLOGY OF TABOGA, URABl, AND

TABOGUILLA ISLANDS, PANAMA

By MATTHEW W.

andMARION STIRLING

285

682-611—64 24

CONTENTS

PAGE

Preface 291

Introduction 293

TabogaIsland 293

Taboga-1 296

Stone, bone,andshell 297

Ceramics 299

Pottery wares 306

Taboga-2 307

Taboga-3 307

Taboga-4 308

Taboga-5 310

Urabd. Island 310

TaboguillaIsland 312

Taboguilla-1 andTaboguilla-2 313

Ceramics 313

Painted wares 316

Incising 317

Indented 324

Applique 326

Handles 327

Pedestal bases 327

Tripods 327

Stoneandshell 327

Taboguilla-3 336

Referencescited 336

Explanationofplates 337

ILLUSTKATIONS

PLATES

(Allplatesfollowpage 348) 45.

Rim

sherdsfromlarge vessels;Taboga-1.46. Miscellaneoussherds;Taboga-1.

47. Paintedsherds; Taboga-1.

48. Various zoned designs;Taboga-1.

49. Miscellaneoussherds;Taboga-1.

50. Pedestalandring bases; Taboga-1.

51. Tabogastonework.

52. Taboga and Taboguillastoneandshell.

53. Miscellaneoussherds;Taboga-4.

54.

Rim

sherds; Taboga-4.55. Urabdurns.

56. Urabdurns.

287

288 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191PLATES—

Continued57. Siteson Urabd and TaboguillaIslands.

58. Boldincising; Taboguilla-1.

59.

Combing

andincising;Taboguilla-1.60. Incisedware; Taboguilla-1.

61. Variousrim decorations;Taboguilla-1.

62.

Narrow

line combing; TaboguiIla-1.63.

Combed

ware; Taboguilla-1.64. Fragmentsofglobularbowls decorated with

combed

designs; Taboguilla-1.65. Multipleline combing; Taboguilla-1.

66. Scallopimpressions; Taboguilla-1.

67. Filletingon

combed

surface; Taboguilla-1.68. Filletedware; Taboguilla-1.

69. Subglobular bowls withscallopindentedfilleting; Taboguilla-1.

70. CoUanders; Taboguilla-1.

71. Sherdswith bosseddecorations; Taboguilla-1.

72. Broadflatrimsofsubglobular bowls; Taboguilla-1.

73. Subglobular bowls withstrap handles; Taboguilla-1.

74.

Rim

sherdsoffiatshallowplates;Taboguilla-1, 75. Interior ofrim sherdsshown

onplate74.76. Micellaneouspaintedsherds; Taboguilla-1.

77. Black-on-orange-and-blackoutlined with white-on-orange; Taboguilla-1.

78. Black-and-white-on-orangepedestalbasebowlsherds; Taboguilla-1.

79. Reverseofplate78.

80. Pedestal basebowlsherds.

81. Sherdsfrom black-and-white-on-orangepedestal base bowls; Taboguilla-1.

82. Miscellaneous black-on-white-and-orangesherds; Taboguilla-1.

83. Miscellaneous paintedsherds; Taboguilla-1.

84. Miscellaneoussherds; Taboguilla-3 rockshelter.

85. Filletedandscallopimpressed ware; Taboguilla-2.

86. Miscellaneoussherds; Taboguilla-2.

87. Miscellaneoussherds;Taboguilla-2.

88. Miscellaneoussherds; Taboguilla-1.

89. Miscellaneoussherds;Taboguilla-1.

90. Taboguilla-3; rockshelter siteonTaboguilla.

TEXT FIGURES

PAGE

25.

Rim

profiles;Taboga-1 30026.

Rim

profiles;Taboga-1 30127.

Rim

profilesofred paintedware; Taboga-1 30228.

Rim

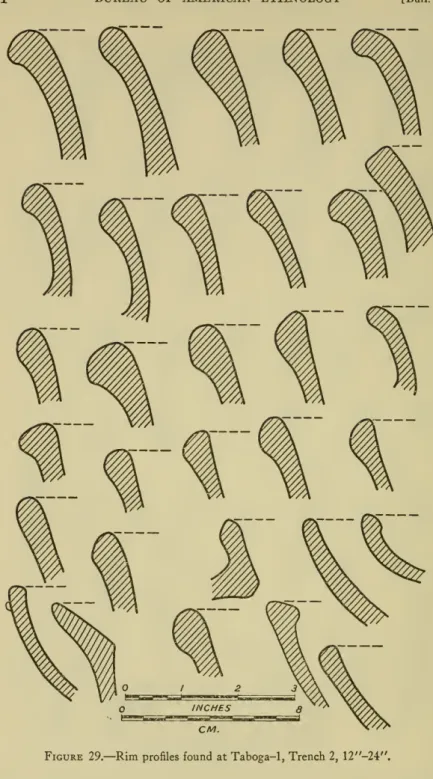

profilesfromlargevessels;Taboga-1 30329.

Rim

profiles;Taboga-1 30430.

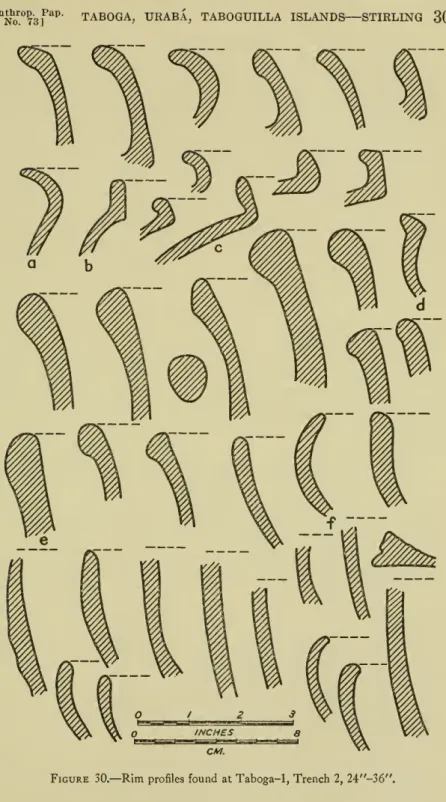

Rim

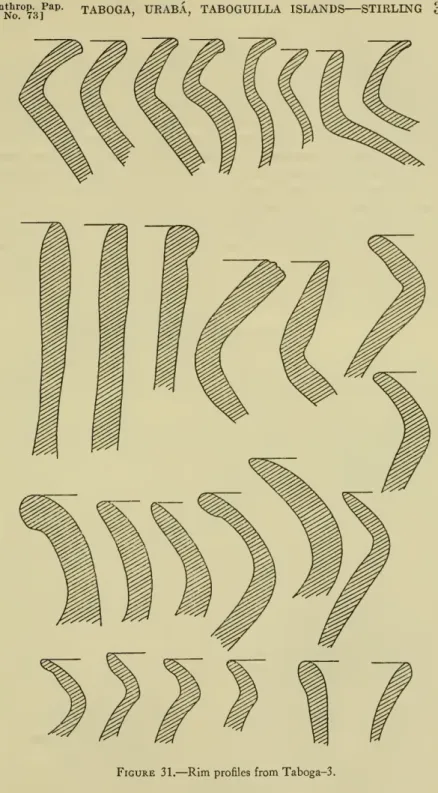

profiles; Taboga-1 30531.

Rim

profiles;Taboga-3 30932. Smallpotswith miniaturesaucersfrom Urabd, 311

33. Taboguillarimprofiles 313

34. Taboguillarimprofiles 314

35. Restored Taboguillabuflfwarejar 315

36. Restored Taboguillabuflfwarejar 316

37. Restored Taboguilla ceramicbowl 317

"^°NJ!°7'3f'''''

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 289 TEXT FIGURES—

ContinuedPAGE

38. Interiorof (figure37) 318

39. Restored Taboguilla orange-and-whitebowl 319

40. Restored Taboguillaincisedjar 319

41. Restored Taboguillaincised jar 320

42. Restored Taboguillaincisedjar 321

43. Restored Taboguillaincisedjar 322

44. Taboguillaincisedsherds 323

45. Restored Taboguillabuffware jarwithscallopindentedfilleting 324 46. Restored Taboguillabuffwarejarwithscallopindentedfilleting 325 47. Restored Taboguillaincisedjarwith applique crescents 326

48. Restored Taboguillapedestalbase bowl 328

49. Restored Taboguillapedestalbase bowl 329

50. Restored Taboguillapedestalbase bowl 350

51. Restored Taboguillapedestalbasebowl 331

52. Restored Taboguillapedestal basebowl 332

53. Restored Taboguillapedestalbase bowl 333

54. Restored Taboguillapedestalbasebowl 334

55. Restored Taboguillapedestalbasebowl 335

PREFACE

The

archeological investigationson Taboga, Uraba, and Taboguilla

Islandswere conducted

inMarch and

April of 1953 as part of the archeologicalprogram

inPanama under

the auspices of theSmith-

sonian Institutionand

theNational Geographic

Society.Accompanying

the expedition asphotographer, and

assistinggen- erally in thework throughout

the entiresequence

of expeditions toPanama, was Richard H.

Stewart, assistant chief of thePhotographic Laboratory

oftheNational Geographic

Society.We

areindebted

to anumber

of friendsboth

in theRepublic

ofPanama and

theCanal Zone

formaking our work

easierand more

efficient.

Mr. Karl

Curtis,longtime

residentof theCanal

Zone,gave

unstintingly of histime and knowledge

ofPanamanian

archeological sites.Mr. and Mrs. Paul

A.Bentz

kindly allowed us to use the largebasement

of theirhome

inBalboa

for the storage ofour specimens and

asawork

laboratory.Above

all,we

are obligatedtoDr. Alejandro Mendez,

director of theAluseo Nacional de Panama,

for his cordial cooperationand

assistanceduring

all ofour

archeological investiga- tions inPanama.

Others, toonumerous

tomention, gave

us assist-ance

inmany ways and

contributed tomaking our

stay inPanama

avery

pleasant one.We

are grateful toMr. Edward G. Schumacher,

artist for theBureau

ofAmerican

Ethnologj'', for thelinedrawings

in this report.291

THE ARCHEOLOGY OF TABOGA, URABi, AND

TABOGUILLA ISLANDS, PANAMA

By Matthew W. and Marion Stirling

INTRODUCTION

The

islands ofTaboga, Uraba, and

Taboguilla lie in theGulf

ofPanama some

12 milesfrom

the Pacific entrance to thePanama

Canal. All three are relatively steep

mountain peaks which

projectabove

thewaters

ofthegulfand, asaconsequence, thereisaminimum

of level

ground on them. Uraba and

Taboguilla lack freshwater during

thedry

season,and

as a resulthave

at the presenttime no permanent

inhabitants.Uraba

issmalland rocky and has very

little cultivable ground. Taboguilla is largerand has

a considerable area suitable for cultivationand some

springswhich

furnishenough water

fordrinkingpurposes

forallbut

2months

oftheyear.At

the presenttime

there are three or four small houseson

Taboguillawhich

areoccupied

temporarilyby

familiesfrom Taboga who have

plantationson

the island.TABOGA ISLAND

Taboga, about

2 miles in lengthand

1 mile in width, is the largest of the three islandsand

theonly one with permanent

habitations.There

isan ample supply

ofwater and

a smallbut good harbor with good

anchorage. It is avery

attractive placeand now

isfamed

as a pleasure resort.The

area of theBay

ofPanama extending from Taboga

to the Pearl Islands isone

of the world's finest fishing grounds, a factno doubt

exploitedby

the aboriginal inhabitants.In

fact, thename "Panama"

refers to the

abundance

of fish. Fishingnow

istheprincipalindustry ofTaboga

asitprobably was

inpre-Columbian

times.Judging from

thenature

ofthe archeologicalsites, the aboriginesmade

considerable useoftheshellfishwhich

occurinabundance and

considerablevariety.The

principal speciesused was

Aequipecten circularisSowerby, which

constitutesprobably

one-half ofthe totalshell content of themidden

deposits.

293

294 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191Because

of the lack of suitableanchorages

along themainland

of the

Isthmus, and because good water was not

readily available there,Taboga

earlybecame

akey

pointforthe trans-Isthmian traffic.Balboa

scarcelyhad reached

the PacificbeforeTaboga began

acolorful historymatched by few

spotsofequalsizein theNew World.

The

principalstream

ofwater on Taboga

flowsthrough

theonly

relatively level areaon

the island, that lyingimmediately back

of thecove and

beach.The

present village occupies this areaon both

sides of the stream, thehouses being

builtabout

as close together as possible. Since this is theonly

logical living siteon

the island, itwas

here also that the principal aboriginal settlementwas

located.Under

the present village lie theremains

of the old colonialSpanish town, and below

that themidden

deposits of the Indians.A

crosssection of this deposit is

exposed where

theramp from

thebeach

as-cends

to the firstnarrow

streeton

the village level.The church appears

tobe

builtover approximately

themiddle

of theIndian

village site.While

this sitewould be

naturally themost productive

location for archeological research, it is impracticable to dig in itbecause

of thebuUdings which

cover it.At

the presenttime

the surface of theground under and around

thehouses

is litteredwith

amixture

ofSpanish and Indian

sherds.Information concerning

the Indians inhabitingTaboga

at thetime

of theConquest

isalmost

nonexistent.Because

of the early settle-ment

of theislandby

theSpaniards and

itslimitedarea, it isprobable

that thebulk

of the nativeswere

killed or drivenaway

early in the 16th century.After raiding Parita

and

theAzuero Peninsula

in 1515,Badajoz and

his surviving followers fled toChame and thence

toTaboga

Island,

being

the firstEuropeans

toland

there. After nursing theirwounds

for severalweeks

in the security of the island,they returned

to themainland. Beyond

the fact that the island received itsname from Taboga,

the chiefwho

resided there,and

that theSpaniards obtained

22,000 pesos ofgoldfrom

the natives,we

learnnothing from

the early chronicles. It isprobably

safe toassume, however,

thatBadajoz obtained

the goldby

forceand

thathisvisitvirtuallybrought

toan end

the aboriginaloccupation

of the island.In 1519

Pedrarias,then Governor

ofPanama,

after taking posses- sion of thesouth

coast,brought

his force of400 men

toTaboga, from whence he

established the oldCity

ofPanama.

It is tobe presumed

that theSpaniards

alreadyhad

a settlementon

the island, for inNovember

of1524

Pizarro sailedfrom Taboga on

hisepoch-making voyage

of discoverywhich

led to theconquest

of Peru.In

1545,Pedro de

Hinojosa,dispatched by

Pizarro tocapture

Panama and

placeitunder

his control,outfittedand

repairedhisships^°NJ".°73r^^'

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 295

at

Taboga from whence he conducted

hisnegotiationswith

thegovern-

ing officialson

themainland. Dm-ing

all of thistime

there isno mention

of Indianson

the island.In 1575

Dr.Alonso Criado de

Castilla stated that"Five

leaguesfrom

theCity

ofPanama was

the island ofOtoque, and

three leaguesfrom Panama was

the island ofTaboga; both

tilledand

cultivatedby some

inhabitants ofPanama who

plantedand harvested

corn."This would seem

to indicate that the aboriginal populationhad been

replaced in themain by

mestizosand

Spaniards.In

1610, in reply to queries sentout by

theSpanish Crown,

the followingitem

is of interest:The

districts aboutPanama

formerly hadmany

pueblos of Indians, but only threeremained. ThatofChepo waseightleaguestothe east....

Chepo had 40 Indianinhabitants,ruledbytheirown

governor, constable,and twomandadores.On

Isla delRey

[inthePearl Islands] to theeast, 18 leagues fromPanama

and6 leaguesfromTierraFirma wasanother pueblowhichusuallycontained 500 Indians but then only 12.The

third village of natives was on IslaTaboya

[Taboga] 4 leaguessouthofthe City with but12 inhabitants,who

were very poorlikethose of delRey.None

ofthese Indians paid tribute, and all spoke the Spanish lan- guage, havingentirelyforgottentheirown. [Anderson, 1938,p. 281.]Reference

to this patheticremnant

is the lastcontemporary men-

tion of the

Taboga

natives. It is certain that the Indianshad no

partin the hectic events thattook

placeon and about Taboga during

thenext two

centurieswhen

itwas

akey

point in the activities of thebuccaneers and

other freebooterswho roamed

theSouth Sea and

repeatedlyburned and sacked

thetown, which was always promptly

rebuilt

on

thesame

spot beside the clearstream which

here flows into the cove.In

1671,when Morgan sacked Old Panama,

theSpanish

refugees fledby boat

toTaboga and

Taboguilla. Itwas not

long after this thatCaptain

Searleswas

sent to capture theSpanish

treasure ship Trinity;he captured

itatTaboga. The

shipwas

poorlyequipped

for defense,but Taboga was

storedwith

"several sorts of richwines"

with which

Searles'men

"plentifullydebauched

themselves."By

the

time they had sobered

up, the Trinityhad

escaped.Even

as late as 1819Captain

Illingsworthand

hisgroup

of Chileanslanded on Taboga, where they

lootedand burned

the village.A number

of early descriptions of the islandhave been

left usby

the

more

literateof the buccaneers.That

ofCapt. William Dampier,

written in 1685,would

servevery

well to describe the Island today:The

24th daywe

run overto the Island Tabago. Tabago is inthe Bay, and about6 Leagues Southof Panama. Itis about3mile long, and2broad, a high mountainous Island.On

the north sideit declines with a gentle descent to the Sea.The Land

by the Sea is of a blackMold

and deep; but towards the top of the Mountain it is strong and dry.The

North side of this Island makes a296 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191very pleasant shew, it seems to be a Garden of Fruit inclosed with

many

high trees; the chief est Fruits are Plantains and Bonano's.They

thrive very well fromthefoot tothe middleofit;butthosenear the toparebutsmall, aswanting moisture. Close by the Sea there aremany

Coco-Nut-Trees, whichmake

a very pleasant sight. Within the Coco-Nut-Trees there growmany Mammet (Mame)

Trees.... The

S.W. end ofthe Islandhath never been cleared, butisfull of Firewood, and Trees ofdivers sorts. There is a very finesmall Brook

offreshWater, thatspringsoutoftheside of the Mountain,andglidingthrough the Groveof Fruittrees, falls intothe Sea ontheNorthside. There wasasmall

Town

standing by the Sea, with a Churchat one end, butnow

the biggestpart of it is destroyed by the Privateers.The

buccaneers under Sawkins lay here fromMay

2-15, 1680.['] Thereis goodanchoringrightagainsttheTown, about a mile from the shoar, where youmay

have 16 or 18 fathom Water, soft oazy ground. Thereis a small Islandclose bytheN.W.

endof this called Tabogilla [actually Urabd], with a small Channel to pass between. There is anotherwoody

Island about a mile on the N.E. side of Tabago, and a good Channel between them: this Island [Taboguilla] hath noName

that ever I heard.[Dampier, 1717.]

It is clear

from

the ratherabundant

literatureconcerning Taboga,

thatfrom

earliest times, togetherwith Taboguilla and Otoque,

itwas

the vegetablegarden and

fruitorchard

first forOld Panama, and

later toa

lesser extentfor themodern

city.It is interesting to

note

theapparent changes over

the centuries in the characterof the crops raised.In

1575, the principal cropwas

corn.

In 1685 Dampier

states that the chief cropwas

plantainsand bananas, but

alsomentions coconuts and mames. At

the presenttime

the principal crops are pineapplesand papayas, which

aregrown

in clearings

on

the steep hillsides.The

pineapples ofTaboga

arefamous

for their quality,and

it is local tradition that the original plantings for theHawaiian

Islandscame from

here.The

aboriginaloccupants

ofTaboga were probably moderately

prosperous, sinceBadajoz

lootedthem

ofafairly substantialquantity

of gold.A few

years ago,our workmen

told us, a gold"Corona,"

a plain

band

of goldabout

1 inch in width, tobe worn around

the head,was washed

out of thebank

of the creek.The

finders dividedit equally

among themselves by breaking

it into three parts.Lo-

throp illustrates several goldspecimens

said tohave come from Taboga.

With

the aid of nativeswe were

able to locate severalmidden

sites other

than

thatunderlying

thevillage.TABOGA-1

Near

the northeasternextremity

ofTaboga

is a small cove,back

of

which

islocated thestationfrom which

isoperated

aradar

installa- tionon

thesummit

of the island.Above

the station,atan

elevation»"Whilewewerehere," saysRiogrose(1684),"someofourmenbeingdrunkonshore,happenedto set fireunto oneofthe Houses,thewhich consumedtwelve housesmorebeforeanycould get ashoar to quenchit."

^"Noi^TSp"^'

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS STIRLING 297

of

about 350

feet, theground

levels offsomewhat

at a pointwhere an ephemeral stream runs

during thewet

season.On

this areagrow

anumber

ofmango and

lime treesand

afew coconut

palms.Taboga-1

is amidden

deposit consisting of amixture

of shellsand

black earthand

coveringan

areaapproximately

100 feet in dia-meter on

thesouth

slope of a shallowdry

ravine.About

6 inches of black soilcovered

themidden

deposit.Under

this the shell layer decreased indepth from

36 inches at the north, or lower,end

to24 inchesatthe

south

end.Under

theshellthe naturalbase was

avery hard packed mixture

ofrough

rocksand

clayey soil.We dug

a test trench into thisbase

to adepth

of 2 feetwithout

findingany

artifacts.

Trench

1was

laidout 20

feetX 20

feetand excavated

in four sections

each

5 feetX 20

feet in dimension.The

materialwas removed

in 1-foot layers0-12

inches,12-24

inches,and 24-36

inches.STONE, BONE, AND SHELL

Although

potsherdswere

fairlyabundant through

the depositand

stone artifactswere moderately common,

therewere no

artifacts of shell or bone. Shellswere abundant and

in considerable variety, 33 species being collected. Itisinteresting tonote that thespecimens from

themidden average

a considerably larger sizethan

thesame

species living in these

waters

today.The

followingwere found

inTaboga

1:^Gastropoda

Tegula (Tegula) pellis-serpentis

Wood

Neriia {Ritena) scabricosta Larricarck Cypraea (Macrocypraea cervinetto) Kiener Planaxis planicoslatus Sowerby

Siroinbus peruvianus Swainson StrombusgraciliorSowerby Strombiis granulatus Swainson Malea ringensSwainson Thais {Vasula) melones Duclos Muricanthusradix Gmelin Muricanlhus nigritusPhilippi Turbinella castaneaReeve

Fasciolaria (Pleuroploca) princeps Sovvrerby Fasciolaria (Pleuroploca) nalmo

Wood

MelongenapatulaBroderipand Sowerby Mitra {? Sirigatella) belcheri HindsVasum

caestus BroderipTerebrasp. (worn)

Terebra (Sirioierebruv) glauca Hinds

2Tlieidentificationsweremade byDr.R. Tucker Abbott. NomenclaturefollowsthatofA.M.Keen

(1958J.

298 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191Pelecypoda

CodakiadistinguendaTryon AreapadficaSowerby

Anadara (Larkinia) grandis BroderipandSowerby Anadara {Anadara) formosa Sowerby

Aequipeden (Plagioctenium) circularisSowerby Lyropecten (Lyropecten) subnodosusSowerby Ostreachilensis Philippi

Chama

frondosaBroderipTrachycardium (Trachycardium) consors Sowerby Periglypta multicostataSowerby

Chione (Chione) californiensis Broderip Protothaca grata Say

Megapitariaaurantiaca Sowerby

Baknacle: Tetraclitasquamosapanamensis Pllsbry

Fish bones were

presentinsome

quantity,but were not

asabundant

as

might have been

expected.The most common

shellfishwas

Aequipectencircularis,which

constitutedapproximately

one-halfofthe totalnumber. No mammal

or birdbones were

recovered.The most abimdant

stone artifacts consisted ofround

polishing stones,hammerstones and manos,

orgrinding stones, alladapted from

naturallyshaped beach

stones.One broken metate

legwas found

in layer0-12

inches.Three

rather crude,blunt

stone celtswere

found,two

inlayer0-12

inches,one

in12-24

inches.The manos were

ofno standard

shape,but

generally short ratherthan

long,and somewhat

flat in cross section.

The

polishing stonesand hammerstones

varied in sizefrom

that of agolf ball tosomewhat

largerthan

a baseball.In

the12-24

inch levelwas an

interesting gravermade from

a lamellar flake of yellow flint.Since the concentration of

midden

materialseemed

to increasetoward

thenortheast corner of trench 1we

laidout

trench 2,25X25

feet parallel totrench 1,

and

just to thenortheastofit.Over

aportion of this areawas

a stone rectangle, 19 feet square,which

layon

the surface, possibly ahouse

foundation.Some

of the stonesweighed from 200

to300 pounds

each.In

trench 2, themidden

layer variedfrom

32 inches in thickness along thewest

wall to24

incheson

the east wall.We

carried the excavation toan

actualdepth

of44

inches, finding thebase

material tobe

thesame

as in trench 1.We

could findno

traces of a floor or structureunder

the stone "foundation."In

general, the contents of themidden were

similar to those in trench 1,but

stone objectswere somewhat more abundant.

In the0-12

inch levelwe found two

legless metates;one

rectangular, the other oval.The

latterhad been worn

so thin that a holehad formed

in thebottom. In

this levelwas

also a smallbut

well polished celtwith

a sharp cutting edge, anumber

ofhammerstones and manos made from

^'^Noi^Tsf'^^''

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 299

beach

stones,and

ayellowflintarrowhead

of therough

prismaticform

characteristic of

Veraguas and Code

sites (pis. 51, 52).In

the12-24

inch levelwas another

oval legless metute,and two

peculiarwell-made

large polished stone "axes" ofan

oval shape.In

this level therewas

alsoan

interestingcarved

stone bird effigy 7.5cm.

long (pi. 51),and

asecond

large prismatic flintarrowhead.

Near

thiswas

a deposit consisting of severalhundred unworked

sharks' teeth.CERAMICS

The

potsherdswere broken

into relatively smallfragments

inboth

trenches,and not

asinglecomplete

vesselwas

found.In

trench2 at adepth

of20

incheswas

asmallred-painted subglobularjar,broken

intomany

piecesbut almost

complete.Typical

potteryforms

are globularand

subglobularbowls with

restricted orifices, hemispherical bowls,and oUa shapes with

out- flaringrims

or collared necks.More

elaborate vesselswere

pedestaland

ringbase

bowls.Some

of the pedestal bases are shortand

squat, others talland

slender.The

pedestalbowls were

typically decoratedwith

blackand white

designson an orange

base.The

designswere sometimes on

the ex- terior,sometimes on

theinterior of the bowls. Frequently, red paint alonewas used on

the interior, the exterior, or both.Often

itwas

appliedonly

to the lip or theneck

of the vessel.Simple

designs in blackwere sometimes put on

thered base.There were two

types of red paint used;one

a truedark

red, the otheran orange which

variedin tonefrom

yellowish to red.The two shades

occasionallywere

appliedon

thesame

vessel to give a contrast- ing design.Sometimes white

orcream was used

as a base,with

designs in red or orange.In

at leastone

instance theorange

designswere

outlinedwith narrow black

lines.Modeled

designswere

infrequent.Some

subglobularbowls were

decoratedwith

curving, parallel, raised ridgesimpressed with

scallop shells.These

vesselshad

horizontal loop handles.Sherds from two

plain red

bowls

of thinhard ware were

decoratedwith rows

of raised bosses. Incisingwas

rathercommon and was

usually in connectionwith zoned

designs.Punctate

decorationswere almost

invariably of thezoned

variety.Large

ollas oftenwere

decoratedwith brushing

orscallopcombing,

especiallyon

the necks.The

best idea of the potteryand

decorative techniquescan be obtained from

the illustrationsand

plate descrip- tions.300 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

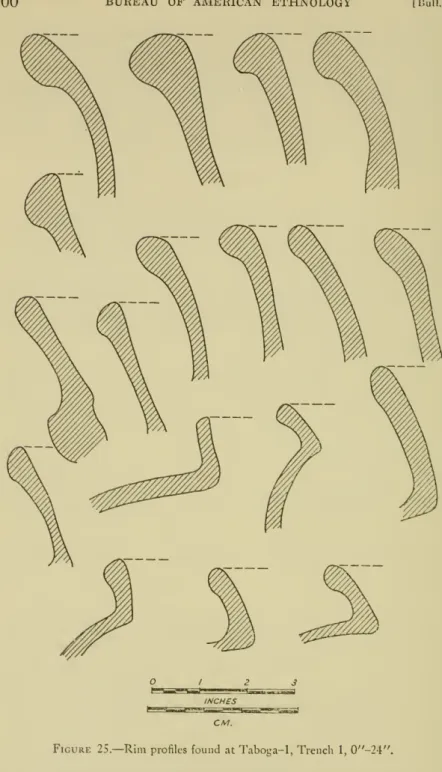

[lUill. 191Figure 25.

—

RimprofilesfoundatTaboga-1,Trench 1,0"-2-l"."^"No'l^Tsf^^'

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 301

CM.

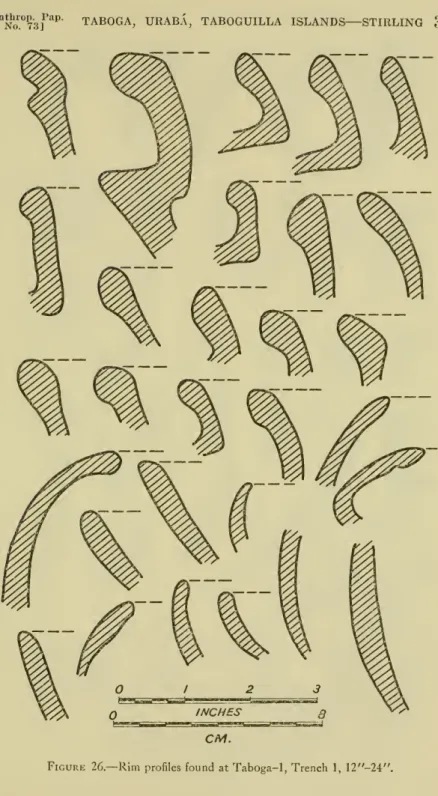

Figure 26.—Rim profilesfound atTaboga-1,Trench 1,12"-24".

682-611—64 25

302 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191CM.

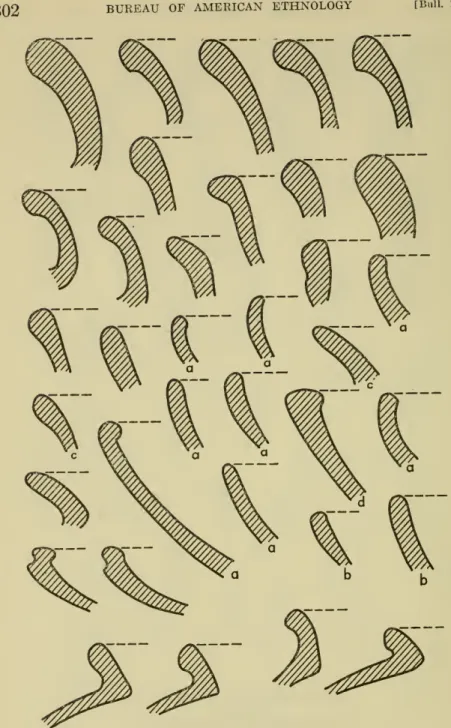

Figure 27.—Rimprofilesofred paintedware found atTaboga-1,Trench2,0" 12' .

"^^No^^T'sf^^

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 303

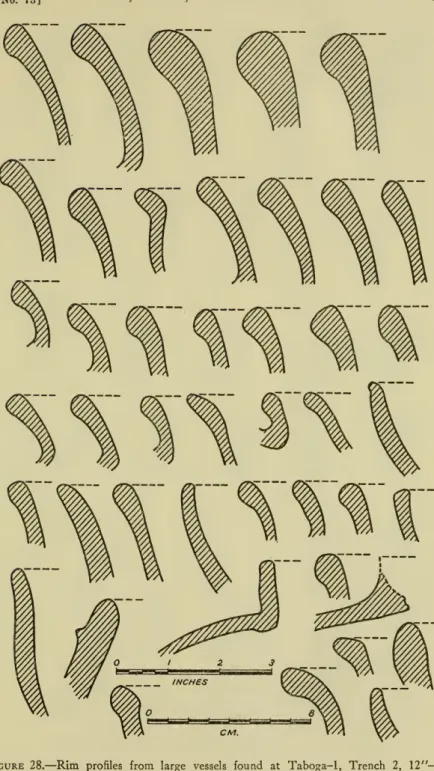

Figure 28.

— Rim

profiles from large vessels found at Taboga-1, Trench 2, 12"-24"304 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191CM,

Figure 29.

— Rim

profilesfoundatTaboga-1,Trench2, 12"-24".^^NJ^^Tsf^^'

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 305

CM.

Figure 30.

—

RimprofilesfoundatTaboga-1,Trench2,24"-36".306 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191 POTTERYWARES

Buf

ware.— There

are threeprunary

types ofware

atTab-1. Un-

slipped buff

ware

is themost abundant. The majority

of these vesselswere more

orlessglobularjarswith

short collarsand

outfiaringrim with thickened

lip.In

12 percent, the lips arepainted

red.Using Munsell

equivalents, the surface color variesfrom an orange

cast5YR

6/6, toa yellowishcastlOYE,

7/6.Sometimes both

of these variantscan be found on

thesame pot

as well as gray, orange,and brown

firing clouds.Therefore

the exactshade

isnot

particularly significant.The

exteriors of the pots generally are wellsmoothed.

In some

cases there are surface striationsfrom dragging

oftemper

particles

during smoothing. The

interiors arenot

as well finished.Some show narrow marks

of asmoothing implement such

as a pebble, orwider marks

asfrom

a gourd.The

surface is slightlyrough

to the touch,and

sherds thathave weathered

aresandy and

granularon

thesurface. It isprobable

that thisware was

self-slipped.Buff ware

varies considerably in the color of the paste. Itsome-

times is firedwith

agray

coreand

buffmargins

of equal thickness.Sometimes

thegray

core is95

percent,with narrow

buff margins.Occasionallyit is

completely

buff, evidentlyastheresult ofbeing

firedmore

heavily.These

variationshold

forvery

thin as well asvery

thick ware.Tempering

material is granularwith angular

particles,medium

to coarse in texture.

In some

instancestemper

isused moderately;

in others, heavily.

Flakes

ofwhite and

red usually aremixed

in.The

pottery doesnot break

evenly; the fractures arerough and

granular.Thickness

in buffware

variesfrom

6mm.

to 23mm.

Orange

Slipped.— The shapes

in general are thesame

as the buff ware, excepting that therewere

afew

shallowbowls with

outflaring rims.The

slip ismoderate orange 5YR

5/6with

splotches of lightbrown

5YR

5/6.The

slipped surfaces oftenshow

fine parallel ridges,made by

the polishing stone,which

arerough where

the sliphas weathered away.

Particles of

mica

glistenon

the surface.The

orange-slipped surface issmooth but not

slick.Unslipped

interiors are oftenrough and

granular.This

slipseems

tobe more

thinly appliedthan

is the red slip.The

paste is amoderate orange

in colorvarying

to lightbrown.

Frequently

the runs,and sometimes

the interiors, of thisware

arepainted

red.When

orange-slippedware

ispainted

red, the result is amuch

truerredthan

that seenon

red-slipped ware, eitherbecause

^^Noi^Tsf'''^'

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA

ISLANDS^— STIRLING 307

itis a thicker applicationor,

more

probably,because

itappears darker over

theorange

slip. It is a strong red,5R

4/10.Red Slipped.—

Shsipeswere

lessrestrictedthan with

theother wares.In

addition to the typical buffware

forms, therewere

globular jarswith

straight collarsvarying from

2 to 4cm.

in height.There was one bowl with

a thickened, incurving rim.The

slip varies in colorfrom moderate

reddish orange,lOR

6/8and lOR

4/10 tomoderate

reddishbrown

lOR, 4/8,and dark

reddish orange,lOR

5/8 or 5/6and 7.5R

4/10.The

exterior is wellsmoothed and

thered slip is polishedand

slick to the touch.Usually

the slip contains mica.The

interior issome-

timessmooth, but

often it is leftrough with

particles of thetemper protruding from

the paste.Marks

of the polishingimplement

are frequently visibleon

the surface, givingit a streaked,uneven

luster.The

slip itself ismoderately heavy and

is crazedand abraded

inmany

cases.In

color the paste isweak

yellowishorange lOYR

7/6 toweak orange SYR

6/6and

lightbrown 5YR

5/6. It generally is fired evenly.Red-slipped

potterywhich

isdecorated

isfinertempered and breaks

evenly.The

textureof thisware

isgenerallymedium

to coarsewith angular tempering

material including mica.In some

instanceswhite quartz

is

abundant

giving thefractures a"snowy"

appearance.Red-slipped ware

varies in thicknessfrom

6 to 12mm.

TABOGA-2

About 400 meters northwest

ofTaboga-1, and

at asomewhat

higher elevation, isanother occupation

sitewith

amuch

thinner deposit ofmidden

material.No

excavationswere made

here,but

a surfacecollectionshowed

that the potteryissimilar inmost

respects to that inTaboga-1.

There

isone

pedestalbase bowl painted red on both

the exteriorand

interior;another had black

stripeson

a redbase on

the exterior, while the interiorisplain.The one unique

sherdwas

amedium high

collarrim with

horizontalcombing on

the interiorand

verticalcomb-

ingon

the exterior. Itwas unpainted and had

aflat lip.One body

sherdwas

decoratedwith two notched

raised horizontallines.Our

conclusionwas

that theoccupation was contemporary with Taboga-1

.

TABOGA-3

On

thenorth

side ofthemain

arroyo that flowsthrough

thevillage,and about 600 meters northwest

of the last houses, is arock

shelter308 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191cave

at thebase

of a small cliffabout 200 meters from

the stream.It is

about

16meters

across themouth and

10meters

deep. It evidentlyhad been used

asan

offertory, orburial place,but we found no bones

in it.Although

the earthen floorwas about

1meter

in depth, the cultural material didnot extend below 25 cm. Potsherds were abundant, but

therewere no

shells or otherevidence

ofmidden

material.The

greatmajority

of the sherds consisted offragments

of large ollas,some with smooth, some with combed,

surfaces.The necks

of the ollas frequently aredecorated with

horizontalcombing

orwhat may be

cord impressions.A few body

sherdshad

a red slipon

the exteriorand one had

arow

of bossesaround

the shoulder,made by

pressingfrom

the interior.A number

of sherdswere

car-bonized on

the exteriorfrom

useon

the fire.Some bottom

sherdsfrom

large ollaswere up

to 4.5cm.

in thickness.TABOGA-4

Approximately 400 meters west

of the sandspit that joinsTaboga with El Morro

at thenorth end

of the island, there is a small valleywith

astream

that flowsonly during

thewet

season.About 200 meters above

themouth

of this stream,and approximately

50meters above

sea levelon

thenorth

side of the slope, is amidden

depositabout 40 cm.

deep.We excavated

a trench inapproximately

themiddle

of this, 8meters X

8 meters, saving allof the sherds.We were

struckby

the fact that the potterydiffers considerablyfrom

thatinTaboga-1.

Painted ware

consists typically of redand black

stripeson

a buff orcream

slip.Sometimes black

stripeswere on

ared

slip. Fre-quently

eithertheentire interioror exterior, or both,were

redslipped.The "red"

color variesfrom orange

to red.The more

elaboratelypainted examples were bowl

forms, frequentlywith

flatbeveled

rims.Larger

vesselswere

ollaforms

of buffware with

outflaringrims

or collared necks.The necks

usuallywere decorated with rough comb-

ing,

probably done with

theedge

of a scallop shell.Often

these vesselshad

the lippainted

red.Commonly

theoUa

bodieswere roughened by

brushing.Some

of themore

noticeable points of differencefrom Taboga-1 were

themuch

largerpercentage

ofcombed

orbrushed

ware, the lack of enlarged lips,and

theapparent complete

lack of incising.Stone

artifactswere

rare.There was one crude

celt of a bluishblack

stone,and

quiteu number

of flint chips includingone

long lamellarflake.A°tb'^oP„Pap.No. 73]

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 309

Figure 31.

— Rim

profilesfrom Taboga-3.310 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191TABOGA-5

On

the precipitoussouth

side ofTaboga

there is acave

located directlybelow

the highestpartoftheisland. Itisabout

5 or6meters above high

water.There

isno beach

along thisexposed

part of the island.To

visit thecave we landed from our boat on

arocky

ledgeand

easilyreached

itby

skirting thelower

partof the cliff.The cave

slopesdownward

atabout

a20°

angleand

theentrance

is

not high enough

tostand up

in. Itseems

tohave been

ahigh

nar-row

cleft, the floor ofwhich has been

builtup with bat dung and by

material

washed

infrom

the hillside. It is quite dry.In

climbingup

the short talusbelow

themouth

of thecave we saw

anumber

of potsherds.The cave

isapparently

quitedeep and

is inhabited

by myriads

ofvampire

bats.We

didnot have

lightsand

therefore didnot

enter. It is quiteprobable

that it contains offerings,judging from

thepotsherds on

the talus.URABA ISLAND

The rocky and

precipitous islet ofUraba

lies to the southeast ofTaboga, from which

it is separatedby

anarrow but deep

channel.It

has no permanent water and but

littleland

suitable for cultivation.At

the presenttime

it isunpopulated.

Our Taboga

Island guidetoldus thathe knew

ofsome rock

shelters containinghuman bones and

largepotteryvessels inan

areasorugged

that itwas

practicallynever

visited.With an outboard motor we

leftTaboga, passed through

the channel, and, following thesouth

side of the islet, entered adeep hidden cove

at the southeast corner.From

this pointwe

cutour

way up

a steepspur

of themountain and down

to thenorth

side.Here

isan

impressive cliff ofmassive

basaltabout 60 meters

high.A broad

shelf at thebase

of the cliff iscovered with

a pile ofhuge angular

blocks of basalt fallenfrom

the cliff.We climbed through and over

this tangledmass

of stone,some

of the blocks as big as a small house.The

rocks areovergrown with

tropical treesand

thewhole

area is a roost forhundreds

of pelicans.Our guide asked

us towait

whilehe

located thesite,and

in 10minutes he returned

carry- ing a big oUa.He brought

us to a placewhere

three gigantic blockscombined

toform

arock

shelterabout 4X5 meters

in area.Open

in the middle, thereis

an overhang on both

sides.Looking down we

couldsee a

dozen

ormore

potteryollas,mostly

broken,but apparently

disturbedonly by nature

sincethey had been

placed there.About 30 meters north

of thismain

depository,we found another

containing three pots.We photographed

the offerings asthey

were, then, after cleaningout

theaccumulated

rubbish,photographed them

^''No'!°73p^'

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS STIRLING 311

again. All of the large ollas

were broken

tosome

extentand

inmany

instances pieceshad

fallen into crevices, orbeen covered by

small slabs of stone (pi. 57).

The

largestnumber

ofpotshad been

placedin thenorth

end,where they were somewhat

exposed.Others had been

placed farback under both

the eastand west

overhangs.At

theextreme

rear of the east side therewere fragments

ofhuman long

bones, wellchewed by

rodents. It

appeared

that thebones belonged

to a single individual.Under

the eastoverhang, which was a

sort of two-story affair,more

potswere

placed wellback on

themain

floor.On

the rathernarrow upper

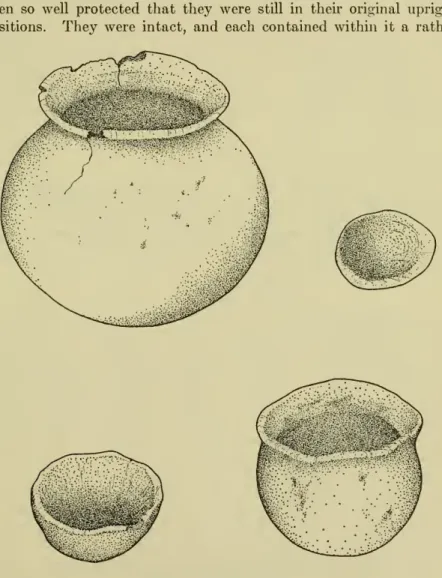

floorhad been put two

small jars.These

latterhad been

so well protected thatthey were

still in their original upright positions.They were

intact,and each

contained within it a ratherFigure 32.

—

Small potswith miniature saucersfrom Uraba.312 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191crudely

made saucer-shaped miniature

vessel.As

nearly aswe

couldtell, there

were

23 potsin all.The

entire collection filled six large potato sacksand

it required threeround

trips forour two men

to transportthem

to the boat.Two oUas were

too large for the sacksand were

carried separately.Two

of the ollashad

traces of red paintand one

small vesselhad a simple geometric

pattern inblack painted on

the interior.The

pottery varies in color

from

lightbuff to brick red,and

isvery

hard.Considering

the size of themajority

of the vessels, thetempering

is

not

coarse.The

wall thickness of the large ollas generally variesfrom

5 to 13mm., but

thebaseson some

are26 mm.

thick.Approx- imately

one-half aredecorated with

ratherhaphazard combing, probably done with

a scallop shell.The remainder

aresmooth and

plain.

The

typicalshape

is that of around-bottomed

rathersquat

olla

with

outfiaring rim.One

largeand one

small vesselhad

a bevelaround

the widest part of thebody. The

small potswere made

ofthe

same type ware and were

similar inshape

excepting for thetwo saucer-shaped

miniatures placed inside small vessels as described above.The

large ollas varied in heightfrom 30

to40 cm. The

largestorifice

measured

33cm.

across (pis. 55, 56).It is evident that the pottery deposits

were

burial offerings,un- doubtedly

for bodiesbrought from Taboga. Bones apparently were not

placed in the urns,which presumably contained

food. It isprobable

thatUraba was uninhabited

in prehistoric timesbut may

have supported

limited cultivationby

the people ofTaboga

as itdoes

today.TABOGUILLA ISLAND

On Taboguilla

Islandwe excavated

three sites.Two

of these aremidden

depositson

thewest

side of the island.Taboguilla-1

islocated at

an

elevation ofabout

115meters above

thesand beach where,

at thetime

ofour

visit, afew unoccupied shacks were

located.Taboguilla-2

is atan

elevation ofabout

100meters almost

directlybelow

Taboguilla-1. Since thetwo

depositsseemed

to contain thesame type

of material,we excavated

a test trench inTaboguiUa-2

to

check on

this fact,and concentrated our

effortson

Taboguilla-1,which was

considerably largerand more

productive.The

refuse ofTaboguHla-l

, consisting ofblack

earthmixed with

shell,was somewhat more than

1meter

indepth.Potsherds were very abundant and

in agood

state of preservation.We conducted

the excavations stratigraphically,but our

statisticsshowed no change

in thetype

or proportions of the ceramics.We concluded

that themidden

repre- sented a singleoccupation over

anot very

considerable length of time.Taboguilla-3 is a rockshelter

about

200 meters south ofTaboguiUa-l.

Anthrop. Pap.

No. 73]

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 313 TABOGUILLA-1 AND TABOGUILLA-2

CERAMICS

Considerable

thought and time were put

into a decisionon

thematter

of colornomenclature. The problem

is acommon one

inPanama:

red vs. orange. Since frequently sherdsfrom

thesame

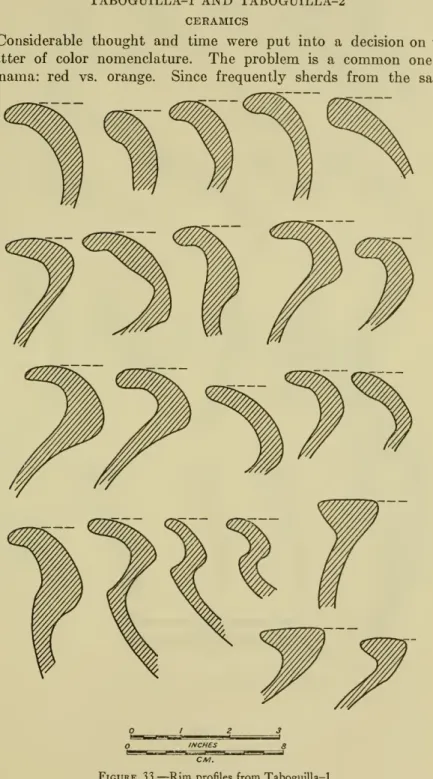

Figure 33.

—

RimprofilesfromTaboguIlla-1.314 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191Figure 34.

—

Rim

profilesfromTaboguilla-1."^"No^Tsf'^^"

TABOGA,

ITRABA,TABOGUILLA ISLANDS STIRLmO 315

vessel

showed

a considerable variation inshade

(from reddishorange

to yellow orange)we

consideredgrouping

allsuch

colorsunder

orange.However,

definite oranges arefound on

interiorsand

exteriors of painted sherdsand

in several instances redwas

appliedon orange

asan

intentional color contrast.We

finally decided to retain the distinction of red, orange,and

bufT, givingMunsell

equivalentswith

the realization that certain vesselsshow

a considerablerange

in hue.The only

truereds areprobably

either the blackon

redtype

or those instanceswhere we have

redon

orange. Vesselsshowing

a color range, forexample,

are (pi. 71, a, c, d),which vary from dark

tones,Morocco Red

(pi. 58) toMadder Brown

(pi. 70),Brick Red

(pi. 70), KaiserBrown

(pi. 71),and Hay's Russet

(pi. 71).The

lighter tones aremore common.

The

oranges areFerruginous

(1YR4.5/8), Vinaceous-Roufous

(10R4.5/9) (pi. 71),and Ochraceous Tawny

(yellow orange) (pi. 72).The

light bufTs are CartridgeBufT

(pi. 87),Cream Buff

(pi. 87),and Light Buff

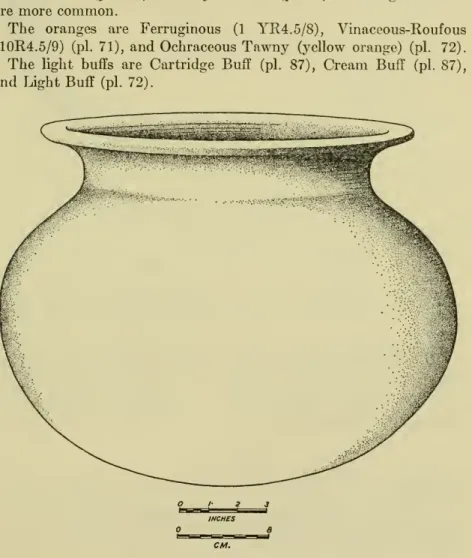

(pi. 72).Figure 35.

—

Restored Taboguillabuffwarejar.316 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191Figure 36.

—

Restored Taboguillaglobular buffwarejar.The browns

arefrom Brown-Bay

toBurnt Sienna

(pi. 59),Mars Orange and Liver Brown

(pi. 71),and

Sanford'sBrown and Hay's

Russet.The only

other colorsused were black and

white. All possiblecombinations

of these three colorswere used

atone time

or another.Although

there isno

inflexible rule, the different colorcombinations tend

to correlatewith

particular vessel forms.A

discussion of decorative techniquesfollows.PAINTED

WARES

Trichrome.

— The majority

of the trichrome vesselswere

pedestalbase

bowls.(a)

Black-on-white

exterior, black-on-orange interiorwith

theorange overlapping

the lip.A

variant of thishas

a plainorange

interior.

^°No?73f^^'

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 317

/NCHES a CM.

Figure 37.

—

Restored Taboguillashallow buffwarebowl.(b)

Black-on-white

interior,orange

exterior.A

varianthas a white-on-orange

exterior.(c)

Black-on-orange

interiorand

exteriorwith white on

the base.(d) Black,

white and orange

exterior, black-on-orange interior.(e) Black,

white and orange

interior,orange

exterior.(f)

Black-and-white-on-orange

interiorand

exterior.(g) Black-and-orange-on-buff.

One

collanderhad

this decoration.Bichrome.

— These combinations

usuallywere

applied to high-necked

globular vessels.(a)

Black-on-white

exterior.(b)

Black-on-orange

exterior.(c)

Orange-on-white

exterior.(d) Black-on-red, interioror exterior.

Monochrome. — This ware

iscommonly

in theform

ofglobular potswith

outflaringrim.(a) Plain orange, interior

and

exterior.(b) Plain orange, exterior.

(c) Plain white, exterior.

INCISING

Bold

incising.— This

is afreehand

techniquewhere deep

parallel lineswere formed,

usuallyin curvilinear patterns.Light incising.

— This

is asomewhat more

delicate technique inwhich

parallel lines usuallywere

applied toform

a crosshatched design.682-611—64- -26

318 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191INCHES

CM.

Figure 38.

—

Interior offigure 37, restored,with blackpainted design.Narrow

line comhing.— This name has been given

to a stylewhere

acomb with

three or four tineswas used

toproduce

a special effect.Bands produced

in thisway were

vertical, horizontal, curvilinear, crosshatched, or squiggled.Multiple line combing.

— As

thename

implies, asharp comb with

more

teethwas

used.The

designs are less precisethan

innarrow

line

combing. Perhaps

tobe

considered a variationof this, iscombing

with

theedge

of apecten

or scallop shell.This

usually is applied rather lightlyand produces an

effect similar to brushing, as the lines arebroad and

shallow.'^°No?7'3r^^'

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGXnLLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 319

Figure 39,

—

Restored Taboguilla orange-and-white bowl; orange body, white shoulder, orangeinteriorandexteriorlip.Figure 40.

—

Restored Taboguillajarwithdeepmultiplelineincising.320 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191a

I

INCHES CM.

Figure 41.

—

Restored Taboguillajarwithdeepmultipleline incising.-^^t^JfoP-of^P-No. 73]

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 321

2 S

1

I/NCHES 3 CM.

Figure 42.

—

Restored Taboguillajarwithdeepmultipleline incising.322 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191Figure 43.

—

Restored Taboguillajarwithdeep multipleline incising.^"Nif.'^Tsf^^'

TABOGA,

URABxV,TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 323

Figure'44.

—

Incised sherdsfrom TaboguIlla-1.324 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191INDENTED

The most common method

of indentingwas

to presswith

theedge

of a scallop shell. Indentations alsowere produced with

awedge- shaped implement. Ordinary punctate

designs,produced with

the point of asharp

instrument, are rare.Usually

thepunctations

are coarse.INCHES

CM.

Figure 45.

—

Restored TaboguillabuffwarejarwithscallopIndented filleting.^"{J'J'^^or^^'

TABOGA, URABA, TABOGUILLA ISLANDS — STIRLING 325

Figure 46.

—

Restored Taboguillabuffwarejarwithscallopindentedfilleting.326 BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY

[Bull. 191APPLIQUE

Filleting.

— Raised

lineswere

applied horizontally, vertically,and

in curvilinear style.Frequently

the filletswere

plain;more

oftenthey were decorated by

indenting, eitherwith

a scallop shell ora wedge- shaped implement.

Animal

figures.—

Filleted designs occasionallywere

embellished furtherwith

stylized figures of lizards (alligators) or frogs.Bosses.

— Hemispherical

bosseswere used

rather frequently.Some-

timesthey were

isolated or in pairs,sometimes

placed close together in parallel lines orin ahaphazard

fashion.a INCHES

CM.

Figure 47.