As the centennial anniversary, 2036, of the novel's publication approaches, Gone with the Wind, as book and film, remains ensconced in the global imagination. People around the world have adopted Mitchell's and Selznick's dramatization – and glorification – of the American South. Margaret Mitchell, author of this epic tale, grew up in the burgeoning city of Atlanta, born at the dawn of the 20th century.

Even closer than Mitchell's home is Marietta's very own Gone with the Wind Museum, located right off historic Marietta Square. For those who hadn't read the novel or been thrown in front of the television, GWTW still loomed large in the imagination of many due to its integral nature in the fabric of their conceptualization of Georgia. Ahmed, drawing on Marx, explains that the weight that increases is actually an excess of the emotions that are generated from.

The expansion of what must be considered in the history of influence allows for a broader interpretation of the text, whether it is the New Testament or GWTW, both in terms of 'meaning'. I will not only look at writing explicitly about the text such as book reviews and academic articles, but also that which sits adjacent to the text or is not particularly concerned with the meaning of the text.

Mitchell’s Narrative Techniques and the Circulation of Emotions: the ‘We’ Voice

While GWTW is certainly not sequential in its use of the collective, the various characters who speak in the voice of "we" in the novel could operate within the first of Lanser's techniques, the simultaneous collective. In her discussion of collective voice, Lanser raises the question of the “limits of individual authorship” for writing the collective “we” (254). Can Mitchell honestly write in the 'we' voice of the South, even just the white South, or is this act too contrived for an author who wants to present 'real' historical fiction.

The narrator's propaganda statements magnify Atlanta's role in The War and in the hearts of the irresistible reader, driving opinions like "(The Battle of Chickamauga) was the. In the final third of the novel, Mitchell's cast of characters regularly meets at the Wilkes'. Irresistible readers are drawn in, not just by the meaning of the word 'they' in GWTW as in the.

Regardless of the reader's level of immersion in the emotional meaning of the text, this passage knows that it is being read. Through the use of collective diction, the understood definition of the other and a metonymic slide, Dr.

Tracking GWTW’s Transition from Novel, to Film, and, Finally, to Idea in

Of the less favorable ones, such as Heywood Broun, Evelyn Scott and Malcolm Cowley, she wrote to a friend. Mitchell sees her novel as an argument for a survival of the fittest, with her white, planter characters in mind. In an early review, Isabel Paterson of the New York Herald-Tribune criticizes the novel.

Mitchell's simple prose, reinforced in power by being so labeled by reviewers, brings a polish of its own. Richard Harwell discusses GWTW's status as a Civil War novel, a genre thought to be one step away from a history lesson for those less familiar with the particulars of The War (1983). He explains a particular rise of the genre in both the quantity of books published and their popularity during the Great Depression as a product of the duration.

Meade's speech to those gathered at Melanie's house which Mitchell places in the aftermath of The War (1983, 89). He continues: "(d)hose (Civil War) novels, and others of the same type, provided the impetus that produced a whole new generation of readers about the Civil War" (10). Reviewers from almost all publications reporting on the book consider the novel realistic in its treatment of the characters and in its presentation of The Civil War and.

Schnell, perhaps with Young's novel in mind, compares GWTW to the overly sentimental Civil War novel: "(o)one gets very little of the idle, gallant, romantic Southern life from this excellent book" (1936). Brickell includes the novel's "authenticity" both because of and in spite of the fact that it is. Samuel Tupper, who makes GWTW "brutally realistic", is of the same southern bent as Brickell.

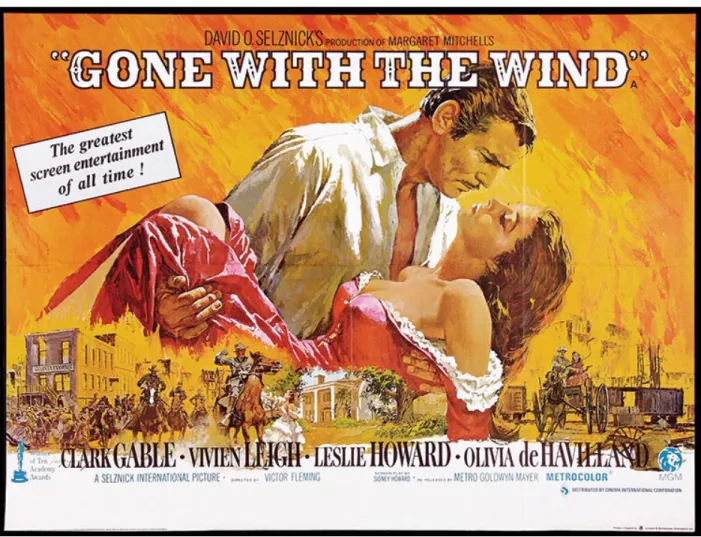

She calls it “the best novel that ever came out of the South” and adds ambitiously that “it is unsurpassed in all American literature.” Southern supremacy, Peterkin gives a reading of the book that focuses on the shortcomings of the southern elite. Romanticization of GWTW seen in the emphasis of the women's perspective and the advent of Selznick's film.

Mitchell's decision to use a women's perspective for her novel was unusual for the Civil War novel genre and was commented upon by reviewers. As evidence of such a woman-centered appeal, Helen Taylor traces the phenomenon of gendered reception of.

Pushing Back: Alice Randall’s Response to GWTW in The Wind Done Gone

Randall confirms this in the last line of acknowledgment of The Wind Done Gone, concluding his book by saying "Margaret Mitchell's novel Gone With the Wind has inspired me to think". GWTW inspired a response to the whitewashed perspective within its pages, a response that pondered how Mitchell's novel differed from the reality of the American South. In the central part of the article, he argues that GWTW is propaganda due to its lack of meditative depth, factual errors, and "overtly patriotic" attitude.

Randall talks about the divergence of the myth of the South held by white characters in GWTW from the truth lived by its black protagonist. GWTW's unreliable narrative identity and Randall's consistent first-person narrator, James Boatwright of The New Republic situates his criticism of the novel in its narrative style. In response to the character of Scarlett as portrayed in the film and novel, his case study is based on psychological theorist Hollender's statement that “(p)ideal climate for the production of hysterical personalities existed in the plantation society of the antebellum South, summarized in Margaret Mitchell's GWTW.

I'll think about it later” or tomorrow in the iconic, commonplace reproduction of the same idea (119). It follows that Mitchell's text is giving a performance of these same southern ideologies through its charming southern narration, aided by its supposed clarity discussed in the previous chapter. Randall undoes Mitchell's performance by revealing the dark reality of GWTW showcases southern ideologies.

Watkins, note the novel's failure to address, as well as minimize, the problem of the 'freed Negro' (1983). Mitchell feigns ignorance of the plight of American blacks, both as slaves and as newly emancipated people. Mitchell's use of the word is ambiguous, but if the answer was the latter, that gives him a little more justification than the former.

Scarlett's freedom from societal constructs, including those that Mitchell anachronistically imposes, such as a taboo on saying the N-word, largely corresponds to the timeline of the freed slave. It is in Cynara's thunderous impact that Randall truly answers Mitchell's ignorance of the problem of the "liberated Negro"; the answer that Randall provides for her reader in The Wind Done Gone is one that centers the issues of our country's entrenched history of slavery and whiteness. Her novel creates a stage for the emotional circulation of the ideologies of white supremacy and anti-blackness.

GWTW can also provide a case study in the storytelling traditions of the white South and how to counter them. The Book of the Month: Reviews.” In Gone with the Wind as a book and film.