Providing quality education requires a safe and orderly school climate with a high priority for academic success (Thapa et al.2013). However, there are different aspects of school climate and motivation, and the question of how instructional quality relates to these different aspects is complex (Good et al.2009). Another important aspect of the school climate relates to a safe and orderly climate (Thapa et al.2013; Wang and Degol2015).

Both safety and order are positively associated with student outcomes in a number of countries (Martin et al. 2013). For further details on the sample, refer to the TIMSS 2011 International Report (Mullis et al. 2012).

Statistical Analysis

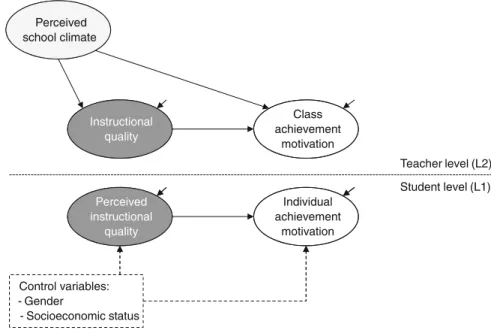

To reflect the socio-economic status of students, a variable was derived from several items in the student survey (students' assessment of the number of books at home, the highest level of education of their parents, and support for home study, such as students having their own room). and internet connection). available in the TIMSS 2011 dataset (the Home Educational Resources scale). We used the person estimate derived from a partial credit model in the TIMSS 2011 scaling procedure (Martin and Mullis2012). Finally, the scalar invariance assumed that the item intercepts were equal in all countries, in addition to the factor loadings.

We evaluated these three invariance models with respect to their overall goodness-of-fit, and the changes in the goodness-of-fit statistics after introducing restrictions on factor loadings and item intercepts. These statistics are particularly sensitive to deviations from the invariance of factor loadings and intercepts (Chen2007). Although these guidelines have been studied and applied in various contexts, we consider them only rough guidelines in the current investigation, as the number of groups is unusually high.

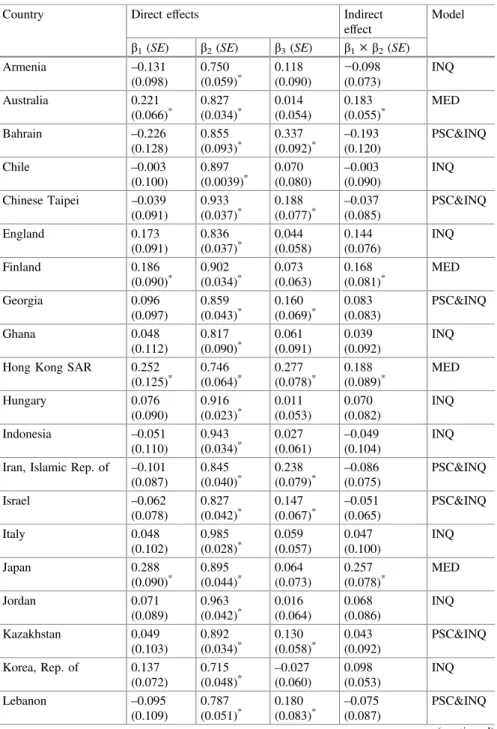

Based on the results of the measurement invariance test, we applied multi-level structural equation models to the data from each of the 50 countries and used the factor loadings obtained from the first step of the class-level invariance testing as fixed parameters in the measurement models of the structures that are being investigated. While we are aware that this country-by-country approach with fixed parameters can result in less accurate parameter estimates than a multi-group, multi-level model approach that estimates cross-country factor loadings, there were significant benefits in reducing the number of model parameters and therefore the simplify model estimation. In this sense, an increase in the RMSEA of less than or equal to 0.030 can still be considered acceptable.

In addition, we included mathematics teacher weights in the analyzes (MATWGT) to account for the sampling design used in TIMSS 2011.

Results

Measurement Invariance Testing

In all analyses, missing data were handled using the maximum likelihood procedure with full information, under the assumption that missing data occurred at random (Enders2010).

Multilevel Structural Equation Modeling

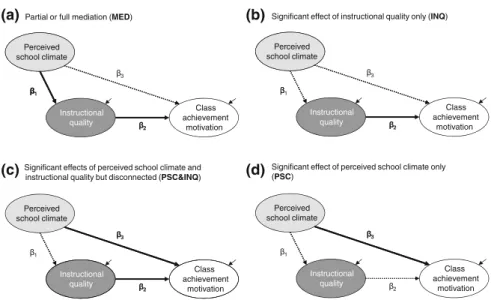

Second, for SEAS and safety in schools, model INQ dominated; The MED model was less common, but could be identified for more than 20% of countries. In addition, model PSC&INQ was supported in 13 countries for students' self-concept and in 10 countries for self-worth. For example, while the PSC&INQ model can be found in more than 20% of countries for SEAS and for the two motivational constructs of self-concept and intrinsic value, this model is significantly less common for students' extrinsic value.

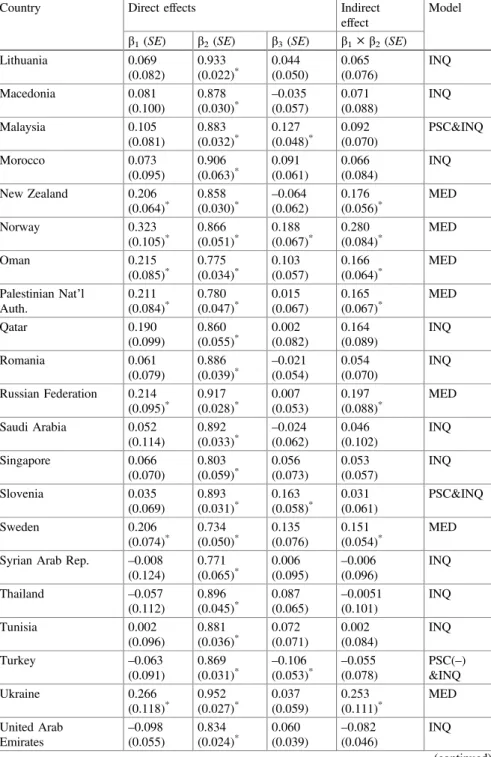

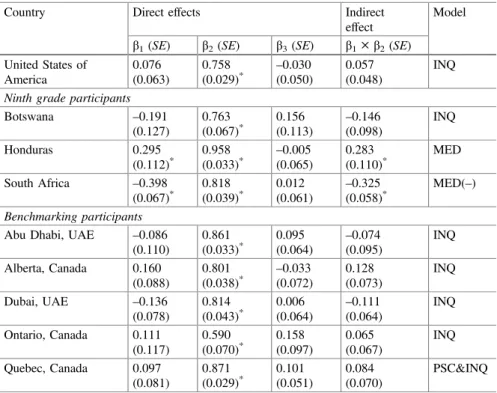

Table 3.2 Overview of existing models that describe the relationship between school climate, teaching quality, and achievement motivation (see Fig. 3.2 for explanation of scenarios) Countries SEASS security Order Self-concept Eigenvalue Extrinsic value Self-concept Intrinsic value Extreme value (N-Self-value concept value (NSelf-value concept value (NSelf-value concept value) −)N/AMED (−)MED(−)N/AMEDINQ AustraliaMEDMEDINQINQINQMEDMEDMED BahrainINQPSC&INQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQ ChilePSC&INQINQINQPSC&INQINQINQINQINQINQ Chinese TaipeiPSC&INQPSC&INQINQPSC&INQPSC&INQINQPSC&INQQINQ EnglandINQINQPSC&INQINQINQMEDMEDMED FinlandMEDMEDMEDINQINQINQMEDMEDMED GeorgiaPSC&INQPSC&IN QINQINQINQINQINDMINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQ SARMEDMEDMEDINQINQPSC&INQMEDMEDMED HungaryPSC&INQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQ IndonesiaINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQ Iran, Islamic Rep.OfPSC&INQMED(−)PSC&INQMED(−)PSC&INQMED(−) −)PSC&INQMED(−)PSC&INQMED(-) QINQINQINQINQINQ ItalyINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQ JapanMEDMEDMEDINQINQINQMEDMEDMED JordanINQINQINQINQMED(−)MED(−)INQINQINQ KazakhstanPSC&INQPSC&INQINQINQPSC(inuDMED)&INQINQPSC(inuDMED)&INt (QINQINQPSC(inud) &IN). Table 3.2 (continued) CountriesSEASSsecurityOrder Korea, Rep.OfINQINQINQINQINQINQINQMEDMEDMED LebanonINQPSC&INQINQINQINQINQPSC&INQPSC&INQINQ LithuaniaINQINQINQMEDMEDMEDINQINQINQINQMINQINQINQINQ MacedoniaINQMINC INQPSC&INQINQINQINQINQINQINQ MoroccoPSC&INQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQ New ZealandMEDMEDINQ QINQINQMEDMEDMED NorwayMEDMEDMEDINQINQMEDMEDMED OmanMEDMEDMEDINQINQINQINQMEDMEDMEDA Palestine ED QatarINQINQMEDINQINQINQMEDMEDMED RomaniaPSC&INQINQINQINQINQINQINQMEDMEDMED Russian FederationMEDMEDMEDMEDMEDMEDMEDMED Saudi ArabiaINQINQINQINQPSC&INQINQINQ&INQINQINQ&INQINQINQ&INQINQINQ&INQINQINQ NQINQINQINPSC&INQIN Singapore SloveniaPSC&INQPSC&INQINQINQINQINQMEDMEDMED SwedenMEDMEDMEDINQINQINQMEDMEDMED Syrian Arab RepublicINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQ (continued). Table 3.2 (continued) CountriesSEASSsecurityOrder ThailandINQINQINQPSC&INQINQPSC&INQMEDMEDMED TunisiaINQINQINQINQINQINQMEDMEDMED TurkeyINQPSC(−) &INQINQINQINQPSC(−) &INQPSMEDMEDMINQINQINCMEDMEDINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQ United States of AmericaPSC&INQINQINQINQPSC(−) &INQPSMEDMED Ninth grade participants BotswanaINQINQPSCINQINQN/AINQINQN/A HondurasMEDfreeMEDMEDMEDMED(MEDMEDMEDMEDMED)−MEDMEDMEDMEDMED(MEDMEDMED)−South. MED(−)MED(−)MED(−)PSC&INQPSC&INQINQ Participants in benchmarking AbuDhabi, UAEINQINQINQINQINQINQPSC&INQPSC&INQ Alberta, CanadaINQINQINQINQPSC(−) &INQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQ QINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQINQ än Canada PSC&INQINQINQINQN/AMEDMED Quebec, CanadaPSC&INQPSC&INQPSC&INQINQINQINQMEDMEDMED Note (–) indicates negative re regression coefficient.SEstandard error.UAEUnited ArabEmirates.*p< 0.05.

Table 3.3 Absolute frequencies of the scenarios (see Fig. 3.2) identified in the 50 participating TIMSS 2011 countries Model SEAS Safety Order Self Concept Intrinsic Value Extrinsic Value Self Concept Intrinsic Value Extrinsic Value Self Concept Intrinsic Value Extrinsic Value INQ MED MED PSC101000000 PSC&INQ PSC(−) &INQ 01104 2000 N/A 100101201 Note(–) denotes a negative regression coefficient. UAE United Arab Emirates. N/A indicates that either relationship between the three constructs was insignificant (p > 0.05) or there was only a significant relationship between school climate and quality of education, with no relationship to the motivational outcome variable. English speaking countries: Mediation was evident for SEAS and order in all motivational aspects in Australia and New Zealand. Asian countries: In Japan and Hong Kong, the relationships between SEAS and achievement motivation, and order and achievement motivation were mediated by instructional quality; in Korea and Thailand, mediation was visible only for order.

Arab countries: The relationship between security and student motivation was mediated in Iran and Jordan; in addition, they mediated the SEAS and order in Oman, Palestine and Qatar. North Africa: The relationship between order and student motivation was mediated by teaching quality in Tunisia and Turkey; mediation was also found for SEAS and security in South Africa. South America: models with SEAS, safety and order as aspects of school climate have shown intervention in Honduras.

Discussion

In England, the United States and Quebec, only the relationship between order and motivation was mediated by the quality of education. Eastern and Central European Countries: Education Quality Mediated the Relationship Between Order and Motivation of Students in Georgia, Romania, Macedonia, Slovenia and Kazakhstan. Collective beliefs, capabilities, and trust among the involved members of the school institution, as evidenced by high levels of SEAS, are important for instructional quality and achievement motivation.

In this regard, we found support for the mediating role of teaching quality in the relationship between SEAS and achievement motivation in a number of countries. The connection between these members, which can be created when everyone is working towards the same goal, seems to affect the quality of teachers' teaching and the motivation of students. In summary, previous research has shown that teaching quality and school atmosphere are related to both student achievement and motivation (Fauth et al. 2014; Hoy et al. 2006; Klieme et al. 2009; Klusmann et al. 2008; Nilsen and Gustafsson 2014). , so it is not surprising that we found that school climate affects motivation.

Although the importance of school climate for student achievement motivation was confirmed in our study, the effects of teaching quality dominated in almost all scenarios. Indeed, previous research has found significant interactions between teaching quality and learning outcomes (Baumert et al. 2010; Blömeke et al. 2013; Fauth et al. 2014), and our results support these findings. Although there are many studies on the relationship between school climate and achievement (see Hoy et al. 2006; Martin et al. 2013; McGuigan and Hoy 2006) and on the relationship between teaching quality and achievement (e.g. Baumert et al. 2010). ), there have been relatively few studies examining the relationships between school climate and teaching quality (Creemers and Kyriakides 2010).

The results support our expectation of a correlation between teaching quality and school climate and point to the importance of SEAS, Safety and Order as important aspects of school climate.

Limitations

First, teaching that focuses on engaging students to learn mathematics also creates opportunities for students to be motivated by the subject. Second, the measurement of teaching quality focused mainly on the engagement part of the construct, and was thus aligned with the measurement of achievement motivation; this adaptation of the measures may have created similarities in how students understand and rate the items presented in the TIMSS 2011 questionnaire. Regardless, this strong association was consistently found in almost all countries and therefore needs further attention.

In addition, the inclusion of all countries and the use of international large-scale studies can also inform policy and practice on the importance of SEAS for teaching quality. It is worth noting that SEAS and teaching quality play an important role not only in students' motivation to learn mathematics, but also in their self-confidence and future-oriented motivation to pursue a career in mathematics and value the subject; this indicates the importance of both the school and classroom environment for career aspirations and for students' evaluation of their own abilities in mathematics, which in turn determines their performance.

Conclusion

Explaining stability and changes in school effectiveness by looking at changes in the functioning of school factors. Relational aggression in school: Associations with school safety and social climate. Journal for Youth and Youth. Five faces of trust: An empirical confirmation in urban elementary schools. Journal of School Leadership.

Seidel (Eds.), The power of video studies in the investigation of classroom teaching and learning (pp. 137–160). Teachers' professional competence: Effects on teaching quality and student development. Journal of Educational Psychology. The impact of school leadership styles and culture on student achievement in Cypriot primary schools.

Multidimensional self-concepts and perceptions of control: Construct validation of children's responses. Journal of Educational Psychology. Factorial, convergent and discriminant validity of the TIMSS mathematics and science motivation measures: A comparison of Arab and Anglo-Saxon countries. Journal of Educational Psychology. Examining classroom influences on students' perceptions of school climate: The role of classroom management and exclusionary discipline strategies. Journal of School Psychology.

Double latent multilevel analyzes of classroom climate: An illustration.The Journal of Experimental Education TIMSS 2011 International results in mathematics.