It is therefore relevant to investigate the benefits of English language skills on the labor market in the local context. In the international literature, studies have largely relied on self-reported measures of English proficiency in survey data. There is also substantial evidence of measurement error and endogeneity bias in the original models.

Being fluent in the dominant language of a country's economy is advantageous in several ways. What is the relationship between English proficiency and the likelihood of employment for South Africans participating in the labor market?”. The employment probability and earnings premium will be measured using a combination of methods to deal with estimation problems that arise when measuring language skills on labor market outcomes (discussed further below).

What is the nature and extent of bias in the coefficients when estimating the impact of language proficiency on labor market outcomes using self-reported measures of proficiency in the South African context?” By substituting endogenous adjusted values, the IV should address endogeneity bias and potential additional measurement errors in the proficiency measure. Thus, individual controls in the wage model will be associated with an error term, resulting in inconsistent estimates (Heckman, 1979).

Thus, a greater reliance on grants in the household may be associated with a lower probability of employment for the individual.

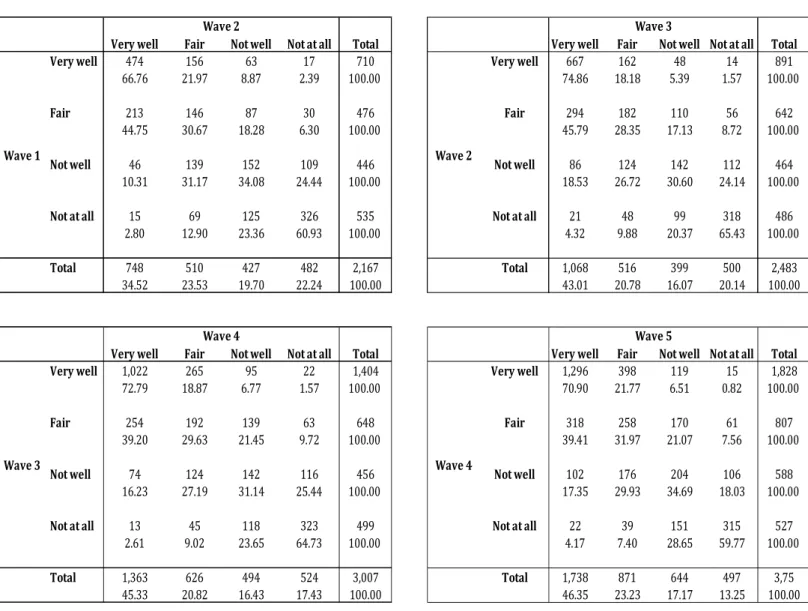

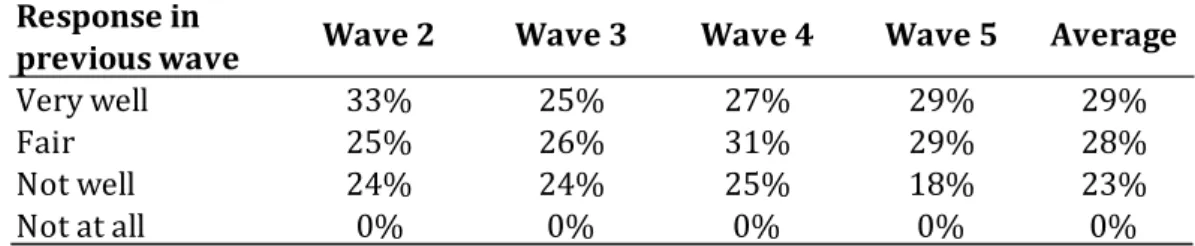

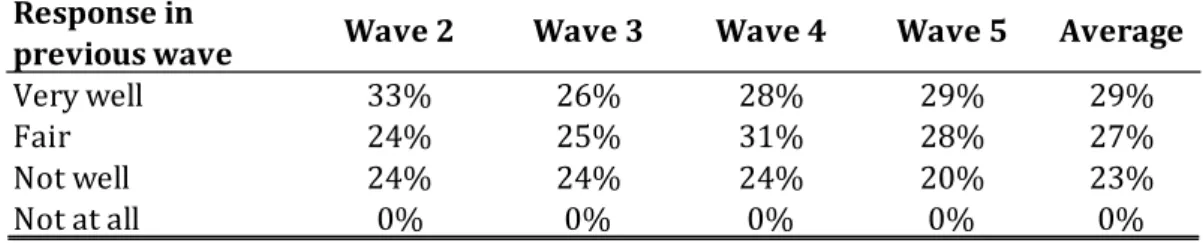

Measurement error descriptive analysis

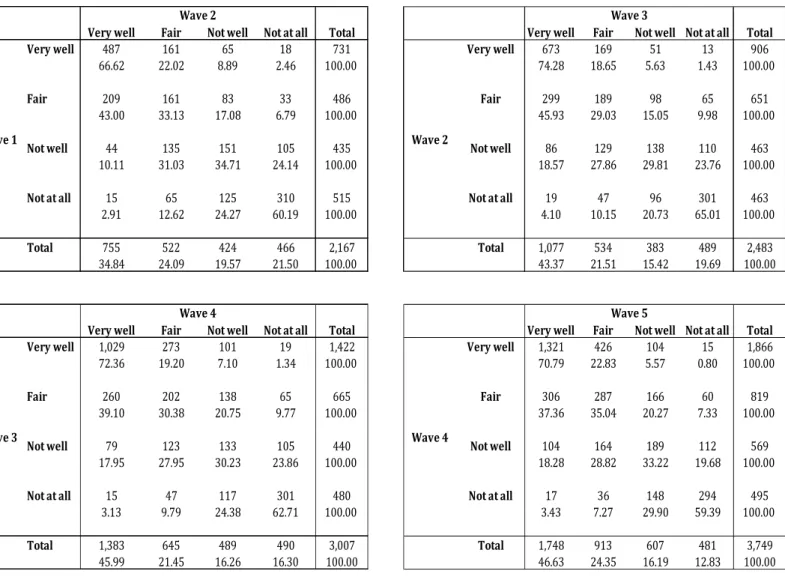

As mentioned above, this property of categorical variables results in measurement error that is non-classical (Schennach, 2016). The correlation between this measurement error and the true values of skill - the first classical assumption. 17 The correlation between this measurement error and the true values of other independent variables in the model - the second classical assumption.

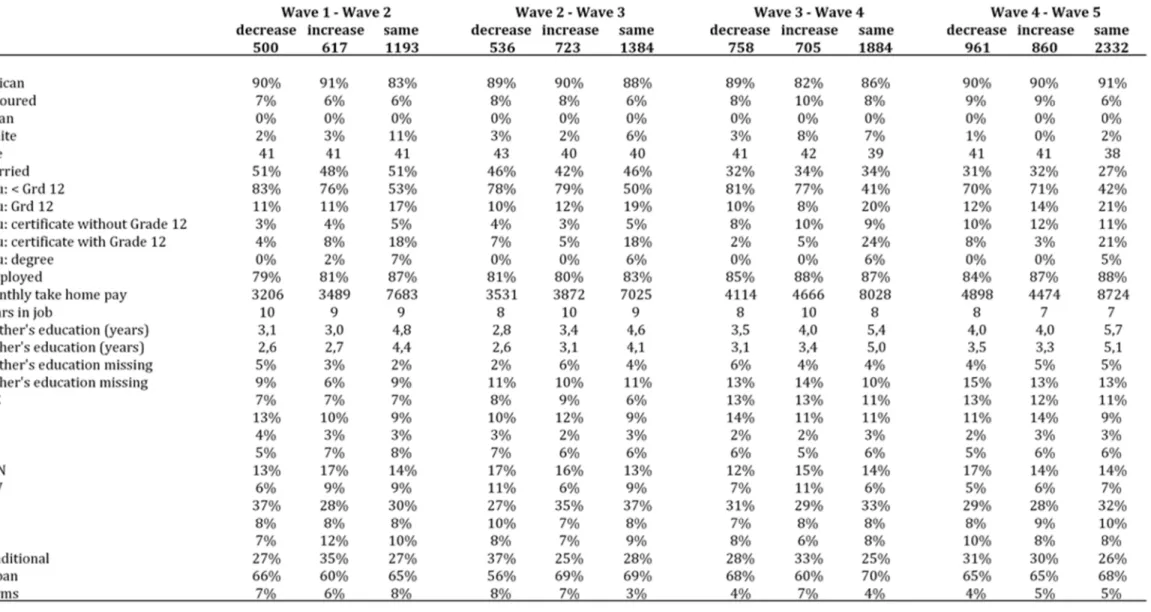

I now investigate whether the assumed measurement error is correlated with the other independent variables that will be included in the employment and wage models. This suggests that the characteristics of those who are more confident in their reading and writing skills (i.e., those whose responses are less sensitive to time-independent measurement error) differ from those who are more uncertain about their skill levels (i.e., those whose responses are less sensitive to time-independent measurement error). . sensitive to time-independent measurement errors). This finding therefore violates the second classical assumption that the measurement error is uncorrelated with the true values of other independent variables in the model.

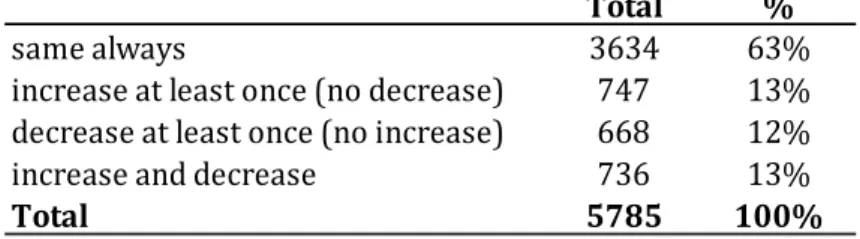

Next, I assess whether and to what extent the observed time-independent measurement error in the skill variables has significance for the regression coefficients on English skills in the employment and wage models. I now examine whether removing responses caused by time-independent measurement error from the English dummy variable has an effect on its coefficients in the OLS wage and employment models. There is thus evidence that time-independent measurement errors may be part of the reason for the unexpected results we have seen so far in the employment models.

This provides further evidence suggesting that time-independent measurement error due to downward revisions may be causing attenuation bias. Note, however, that a difference in the coefficients would also be expected due to the correlation between measurement error and response characteristics (as discussed above). The second type of measurement error is referred to as time-consistent measurement error (Dustmann and van Soest, 2002).

Under the classical measurement error assumptions, both time-independent and time-persistent measurement errors result in skill coefficients that are biased downward to some extent. However, according to the results above, it appears that two of the core classical assumptions may not hold; first, there is evidence that the measurement error is correlated with the true values of skill, and second, there may be a correlation between the measurement error and the true values of other independent variables in the model. However, as mentioned above, the presence of time-persistent measurement errors cannot be observed, and in theory, removing time-persistent measurement could change these results.

Analysis

According to Dustmann and van Soest (2003), this procedure can be expected to eliminate some of the measurement error in the skill dummy that is independent over time. The coefficients in the wage equations are also more than doubled in size when the fit values are substituted (column 7). I make a second attempt to correct for endogeneity bias by accounting for household and spouse characteristics in the models.

While the adjusted coefficients for proficiency in the employment model are significant only in the wave 4 and 5 regressions, they are all slightly smaller compared to those in column 2, where only measurement error was accounted for. Also, in the wage model (column 9), the coefficients are reduced in size compared to those in column 7 (which only corrected for measurement error), but to a much greater extent than in the employment regressions. The wage premium is now estimated at 33 percent, compared to 92 percent previously.

This is much more consistent with the literature and suggests that the coefficients in column 7 were biased upwards to a large extent due to endogeneity in the wage model. With respect to employment, as in the column 4 regressions, the coefficients on the fitted skill variable are still positive in all five Waves and are significant in Waves 4 and 5. When district effects are taken into account, the results indicate that the wage premium associated with a unit increase in English proficiency is in the range of 23-60 percent, or an average of 35 percent.

In the wave 1 and 2 regressions, the coefficients are larger in the model that corrects for measurement error and endogeneity (at the individual and district level) compared to the original regressions using the raw skill measures. The average over the waves indicates that the wage premium is 6 percent higher in the final set of regressions compared to the original regressions—35 percent versus 29 percent, respectively. Thus, the bias due to measurement error appears to be larger than the bias due to endogeneity, leading to an underestimation of the skill effect on wages in the original regressions using the raw skill measures.

Finally, I attempt to deal with an additional source of bias in the wage model, namely selection into employment. However, the change in size of the coefficients compared to those in the wage equations that did not correct for selection (column 10) is inconsistent across waves. Thus, as in the employment model, the negative bias due to measurement error appears to be larger than the positive bias due to endogeneity.

Conclusion

Furthermore, the significance of the inverse Mill ratio indicates the presence of employment selectivity in the original model and therefore one can argue that this correction results in more consistent estimates. Finally, the Heckman selection method was implemented to account for selectivity in the wage model. The results confirmed the presence of selectivity bias in the model, but the direction of the bias in the coefficients was unclear.

Overall, after correcting for time-independent measurement error, endogeneity due to unobserved factors in the models, district fixed effects, and selectivity in the wage model, measurement error appears to dominate both the employment model and in the salary model. In other words, poor English proficiency puts adults at a distinct disadvantage in the labor market—both in terms of entering the workforce and advancing to higher-paying jobs. Specifically, a one-unit increase in the adjusted value of skill is associated with a 23-25 percentage point increase in the probability of employment.

This is the first estimate of the employment impact of English proficiency in South Africa and is consistent with studies in the international literature (for example, Dustmann and Fabbri (2003) find an estimate of 22 percentage points when corrected for measurement error and endogenous selection). This result is 5 percentage points higher than the 27% premium reported by Casale and Posel (2011a) for Afrikaans speakers in South Africa, suggesting that their results may be somewhat biased downward, and is upper end of the range. 5–35 percentage points found in the international literature. Nevertheless, the results show that English language proficiency has a significant impact on both the likelihood of employment and wages in South Africa, in addition to socioeconomic circumstances; thus, regardless of the level of education, training in the knowledge of the English language will be useful for adults participating in the labor market.

Public Policy and Extended Families: Evidence from Pensions in South Africa.’ World Bank Economic Review. Understanding, Speaking, Reading, Writing, and Earnings in the Immigrant Labor Market.’ The American Economic Review. English language proficiency and earnings in a developing country: The case of South Africa.’ The Journal of Socio-Economics.

Language Proficiency and Language Policy in South Africa: Findings from New Data.” International Journal of Educational Development. Language Shift or Increased Bilingualism in South Africa: Evidence from Census Data.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. Language as a 'Resource' in South Africa: The Economic Life of Language in a Globalizing Society.” English Academy Review: Journal of English Studies.

APPENDIX

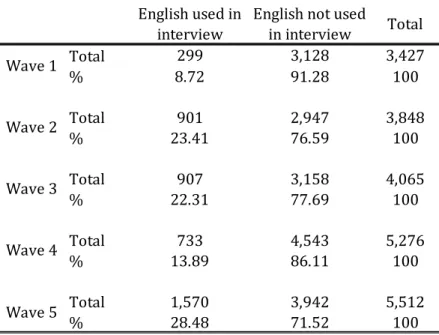

36 Table A7: Two-stage least-squares employment model using English use in interview as an IV. Two stage least squares were used with the instrumental variable for the fitted values of proficiency as an indicator of English. 37 Table A8: Two-stage least-squares wage model using English use in interview as an IV.

Two stage least squares were used with the instrumental variable for the appropriate values of proficiency as an indicator of English use during the interview. Log wage Select Mills Log wage Select Mills Log wage Select Mills Log wage Select Mills Log wage Select Mills.