This is similar to Dupas and Robinson (2013), who examine the impact of four types of targeted healthcare savings instruments with different levels of commitment, while the focus of this article is on savings in the context of agricultural investments and shocks rather than on healthcare . We argue that this is important in the Sahel, as it is in much of the developing world. Overall, our results suggest that different demand patterns for financial products among men and women can lead to wealth differences in the long run.

Again, in this treatment savings were managed by the treasurer of the ROSCA or farmers group to which the participant belonged. Local ROSCAs already provide some form of savings to members and in the Oxfam project "Savings for Change" implemented in Senegal and Burkina Faso (and many other countries in the region) these groups are strengthened and. But ensuring that the savings and insurance decisions made in the session had a real impact on life outside the session allows us to look at the impact of these products on behavior and welfare outcomes.

It also allowed us to use farmers' own subjective expectations about the probability distribution of weather and health outcomes, returns to agricultural investments rather than artificially specifying them in the parameters of the game. 9 savings (T2 and T3) are more effective in boosting investment in productive assets, and. encourage long-term welfare gains.

Selection of participants and data

As Dupas and Robinson (2013) note: “Since much of the value of a savings product appears to be in the mental labeling it facilitates, a product that does not severely restrict liquidity is preferred to one that does, especially for people living in an environment where income shocks are common, such as rural Kenya.” We therefore investigate whether the earmarked product (T2) did create more demand than the higher-commitment savings product (T3) and which of the two had a greater impact on investment. The basic purpose of the study was explained to the individual and he/she was told that participation involved participating in a survey, attending a group meeting in which they would be given money and given the opportunity to choose how to spend it. use, and participation in a survey after the end of the harvest. They then indicated whether or not they wanted to participate in the study and if so, the consent form was signed and the survey continued.

In addition, each participant was asked if he/she would like to receive a gift of 500 CFA at the meeting to which they had been invited. The participant was also asked if he/she wanted to receive a gift of 500 CFA at the meeting to be held in one month, or a gift of 600 CFA to be held in three months at the end of the agricultural season. Their time preferences were recorded and the respondent was given an information voucher reminding them of the details of the experimental session to be held and what their choices on the time preference questions had been.

At the end of the experimental session the next day, the participant received whatever gift he/she chose to receive that day through the time preference questions. In addition, each participant in the experiment was also asked the next day to participate in a standard Binswanger style lottery (Binswanger 1980) in order to measure risk attitudes before the main experiment. Although individuals made choices in this risk lottery before participating in the rest of the experiment, the results of the risk game were not determined (i.e., the coin was not flipped) until the end of the experimental session after individuals had made their recorded main experimental decision. of how much to save or spend on insurance.

11 recorded the amount remaining in the savings product and the amount of agricultural inputs purchased during the fair. Finally, after the end of the harvest, another survey was conducted among everyone who had previously been surveyed. In each country, about half of the participants were literate, while education levels were slightly higher in Senegal.

Nearly a quarter of participants reported experiencing food shortages in the past year due to dry weather, 35% of participants had been sick themselves or their spouses had been sick for more than seven days, and 25% of participants had children who were sick been. seriously ill in the past three months.

Results

Demand

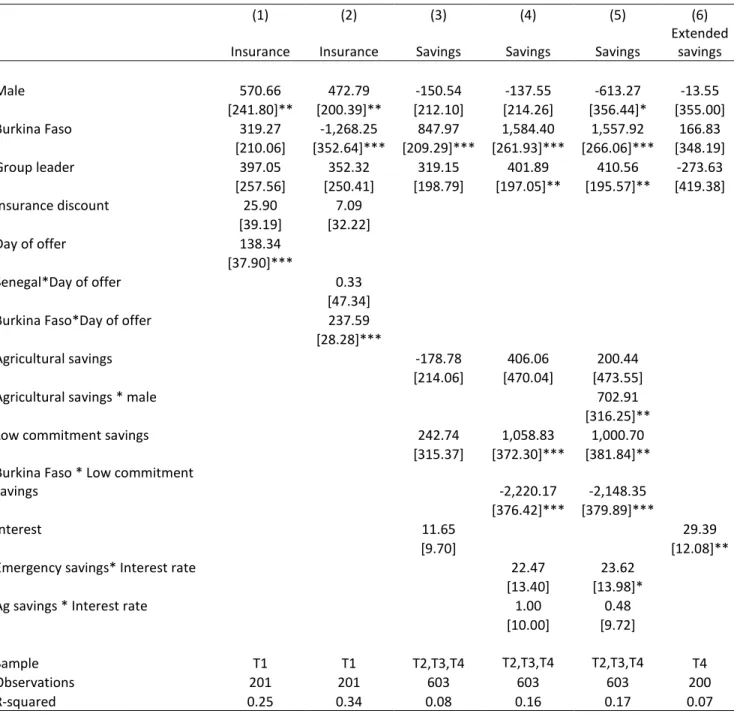

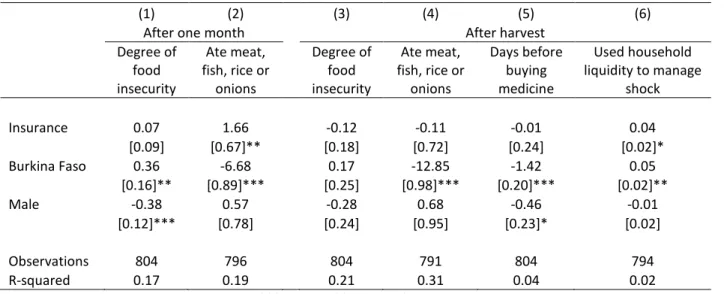

The lower percentage of funds invested in insurance means that individuals in T1 have removed a larger portion of the endowment than those in the savings treatment. 15 participants invested the entire total amount they received in the experimental session in the savings device (Table 5). We will return to this idea of a savings target in the investment savings treatments later.

In Burkina Faso, those who are on emergency austerity treatment decided to save the most. The lowest amount invested in savings was among those under consideration, in which they were offered an envelope for agricultural savings at home. In Senegal, however, it was the most preferred savings option, and the amount saved was the lowest for those who participated in the emergency savings product.

It was not possible to offer interest on the low pledge savings in the home, as we could not monitor how much was in the envelope during the month. The insurance price was given in the session instead of a discounted value from a market price. However, there was another source of exogenous variation in product value, and one that was arguably better understood by the participants.

We offered the insurance product in the last days of the dry season before the rains came. Considering our ordering of sessions was random; this provides an exogenous source of variation in the demand for insurance that can be exploited in instrumental variable estimates of the effect of insurance on the outcome. However, the results in column (5) indicate that gender differences are observed in the amount of savings between savings treatments.

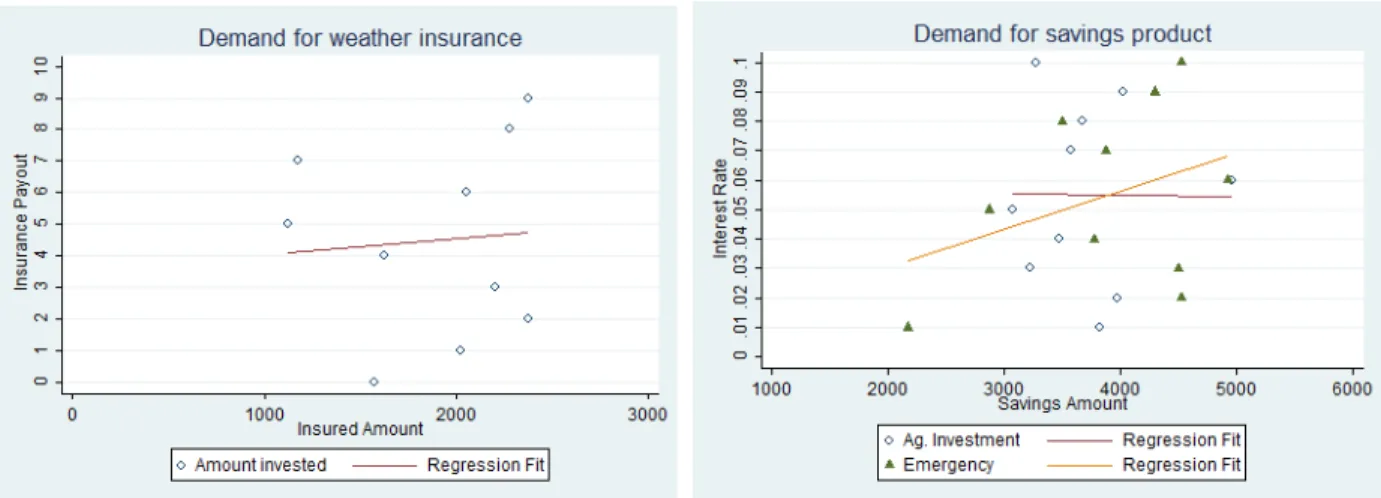

There is no gender difference in the impact of the high commitment treatment in any of the countries. In the case of agricultural investment savings, it is surprising to see that the savings are inelastic to the interest rate (col. 3), in contrast to the positive effect of the interest rate on emergency savings. This is consistent with the idea noted earlier that participants in T2 in Burkina Faso did not believe that the money in the envelope was really theirs.

Impact

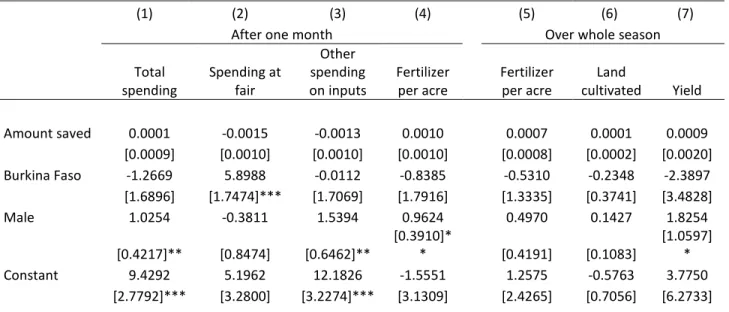

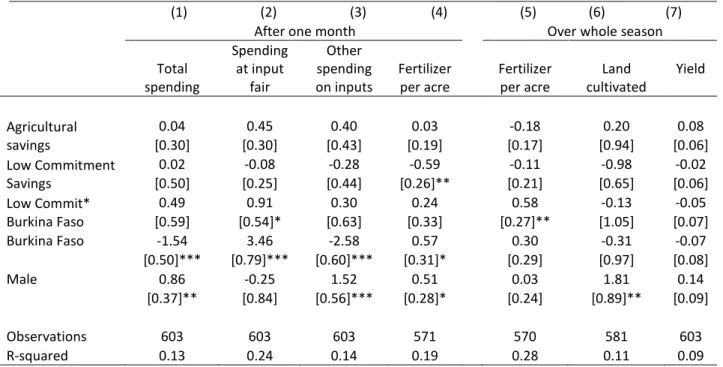

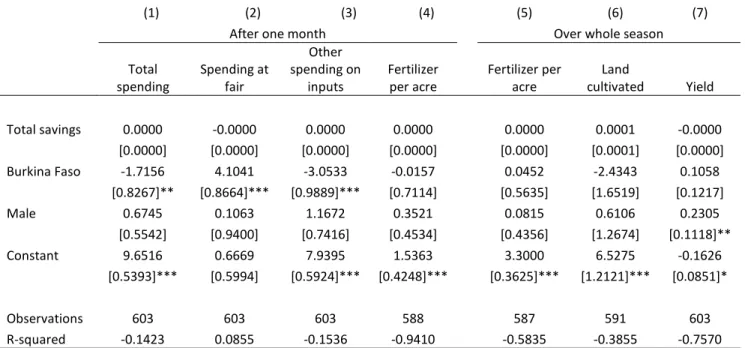

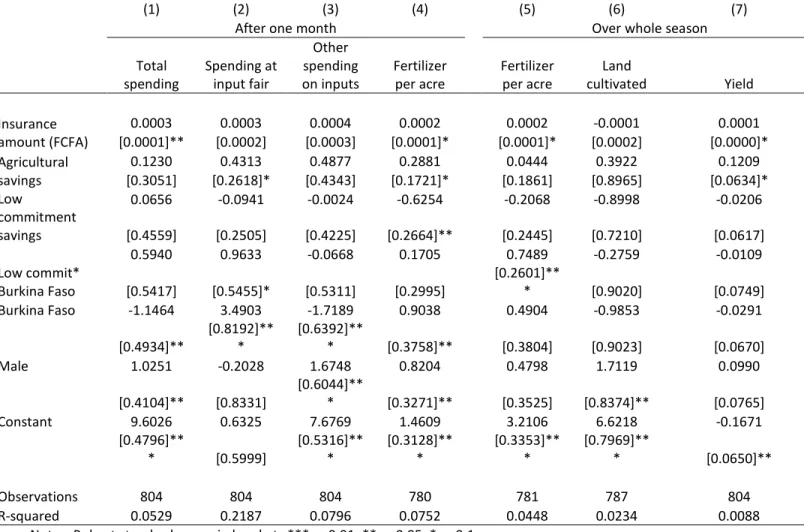

Before turning to the question of the impact of the four instruments, we detail what happened to savings products during the one month between the experimental session and the data fair (for T1 to T4), and during the three months after the fair (for product of extended savings T4+). This helps us understand what might be causing the impact we analyze in the next subsection. No significant difference was observed between the average use of inputs and the output behavior of those in

There was no increase in cropped area (contrary to Karlan et al. 2014). Spending on inputs during the fair itself was not observed by those purchasing insurance, indicating that most of the increase in spending occurred outside of the input fair. 92% of the sample in Senegal did not purchase inputs on the stock exchange, compared to 51% in Burkina Faso.

Farmers in Senegal indeed expected subsidized inputs to be provided by the government immediately after the fair, and at the fair the produce was sold at market price. 22 be a perception among participants in this treatment that any money in the envelope was not really theirs and behavior was consistent with this belief. If this were the case, then it could happen that on the day of the fair when they realized that the money in the envelope was really theirs, this would prompt higher spending at the fair.

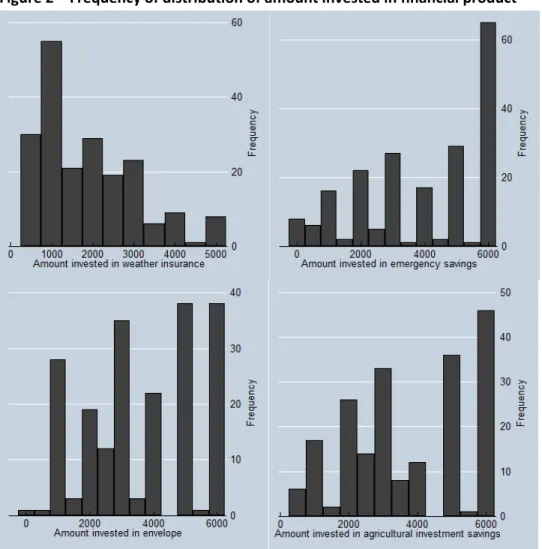

We use the amount contributed to ROSCA in the last 30 days (midline) and the last 3 months (full season) as a proxy for the ROSCA balance. Those in the low-commitment savings treatment in Burkina Faso invested more in ROSCA than those in the other treatments, perhaps indicating that the lower amount of savings in the envelope was compensated by increased savings in other forms. Tables 11 and 12 present the regression results for the various measures of well-being in the month after the experiment and at the end.

The number of days on which luxury foods—meat, fish, rice, and onions—were consumed in the week prior to the survey are reported in columns (2) and (4). Those offered the savings consumed less well one month after the trials than those in the insurance treatment (Table 11, column 2). The difference could partly be driven by the fact that investments in insurance were lower than investments in savings, which meant that people in the insurance treatment received more untied cash home than people in other treatments.

Summary and conclusion

26 outcomes) – for example, the risk of having children due to a very high birth rate or the risk of loss of income and production due to caring for sick children. Further work is needed to understand whether this is indeed a major factor behind the gender gap in demand and, if so, to understand how financial products can be better designed to meet women's different risk needs.

Mutual Insurance as an Elusive Concept in Traditional Rural Communities”, The Journal of Development Studies, Volume 33, Number 6.