Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers canadiens de sociologie 32(3) 2007 341

Consequences

1Max Kashei

Abstract. The concept of “employee lexibility,” and its implementation, have taken a central place in industrial sociology and human resources management during the last several decades. The two types of lexibility most often adopted in the workplace are functional and numerical. Employees and their labour unions approve of functional lexibility more often than numerical lexibility, which is usually rejected. This study is designed to examine the associations between functional and numerical lexibility with job rewards. Using 2002 General Social Survey (GSS) and Current Population Survey (CPS) data, the indings reveal signiicantly higher rewards for functionally lexible jobs while rewards associated with numerically lexible jobs vary signiicantly between and within two major categories — standard and nonstandard jobs. Among those with

nonstandard jobs, independent contractors have signiicantly better opportunity for job rewards than other groups, such as regular part-time or on-call workers. The paper ends with a discussion on the theoretical signiicance of the indings and their policy implications.

emplois non-standard. Parmi les travailleurs, les entrepreneurs indépendants ont une meilleure possibilité des récompenses que les autres groupes d’employés, comme, par exemple, mi-temps régulier ou sur appeler des ouvriers. Cette étude init par une discussion de l'importance théorique de ces recherches et de ses implications possibles sur la formulation de certaines politiques.

During the last few decades, the concept of employee “lexibility,” and its implementation, has taken a central place in social science research as well as in workplace management. Social scientists and policymakers are reach -ing the conclusion that the traditional workplace system, with its bureaucratic and hierarchical control system, is no longer eficient or compatible with the dynamic features of a global economy, which is characterized by global price competition, technological innovation, and network-based production. For an eficient and competitive economy, management needs lexible employees able to “switch gears” and respond to new forms of production (e.g., Appelbaum 2002; Belanger, Giles, and Murray 2002; Cappelli 999; Kalleberg, Reskin, and Hudson 2000; Kalleberg 2003; Osterman 999; 2000; Smith 994; Vallas 999).

A survey of studies reveals that management responses to this ongoing economic transformation have increasingly involved the adoption of two kinds of workplace lexibility: functional and numerical.2 Functional lexibility

re-fers to the ability of employers to deploy or redeploy workers from one task to another with minimal interruption in the work process. Numerical lexibility3

relects employers’ ability to adjust the size of workplace organizations to the changing economy using contingent, temporary, part-time, or other forms of “nonstandard” workers, rather than full-time regular employees, categorized as “standard” employees (Kalleberg et al. 997; Smith 200).

The responses of workers and their labour unions to workplace lexibil-ity are mixed. They often dislike numerical lexibillexibil-ity, since nonstandard jobs mostly are designated “bad jobs,” measured by the degree of earning, pension, and heath insurance (Kalleberg 2000). Numerical lexibility threatens job re-wards — including security, payment, and fringe beneits — for both nonstan-2 Other types of lexibilities, such as “lexible and shift work schedules” (workers

may vary the time they begin or end work), or “pay and wage lexibility” (work-ers’ wages vary with business luctuation) have been discussed in previous studies. These, however, have been neither theoretically well developed nor adopted as an alternative work arrangement in practice.

dard and regular full-time employees (Davis-Blake and Uzzi 993; Kalleberg et al. 997; Olsen and Kalleberg 2004). Findings reported by Kalleberg, Rey-nolds, and Marsden (2003: 545) are consistent with the argument that labour unions dislike numerical lexibility, “because such arrangements threaten the job security or compensation package of regular full time employees.” Mc-Govern, Smeaton, and Hill’s (2004) study in Britain suggests that nonstandard jobs have inferior employment conditions (low pay, no health insurance, and no pension beneits) because they are less likely represented by labour unions (one in three for standard and only one in ive for nonstandard jobs). House-man, Kalleberg, and Erickcek’s (2000: 26) case study in hospitals concludes that the increasing use of temporary help agencies (nonstandard jobs) offered several disadvantages, including “. . . wage discrimination in favor of new en-trants, and lower costs of hiring risky workers” as well as “reduced pressure on companies to raise wages in [a] tight labor market.” Finally, Kalleberg (2000: 359), reviewing the literature on nonstandard jobs, concludes that “there is substantial agreement . . . that nonstandard work arrangements are associated with the lack of health insurance, pensions, and other fringe beneits, this is particularly problematic in the United States since employment is the main source of these beneits.”

Workers and their labour unions have, however, embraced functional lex-ibility. Appelbaum (2002) reported that 70 percent of surveyed workers at the Ford Escort Plant liked their jobs after adopting functional lexibility, especial-ly the teamwork arrangement. In addition, 73 percent of them reported beneit-ing from a functionally lexible work arrangement. Batt and Appelbaum (995) found that over 75 percent of traditional workers said that they would volunteer for teamwork arrangements, given the opportunity. By contrast, less than 0 percent of the workers who hold functionally lexible jobs said that they would prefer their traditional supervisory work arrangement. Finally, Belanger and his colleagues (2002: 62) suggested changing roles and interests for labour unions in functionally lexible organizations. With functional lexibility, labour unions become “more focused on co-operation and problem solving around integrative issues.” Their bargaining mode shifts to organizational innovations, such as “lexibility and cross-trades co-operation on a continuous, rather than a periodic basis.” Overall, such interest in functionally lexible jobs should be attributed to their intrinsic and extrinsic rewards: for instance, workers can par-ticipate in the decision-making process and achieve higher degrees of work au-tonomy, which increases job satisfaction (Belanger et al. 2002; Wright 2000).

standard and nonstandard jobs — contrasting the average rewards associated with standard versus nonstandard jobs, and, occasionally, within nonstandard jobs. Finally, I assess the additive and interactive effects of functional and numerical lexibilities on extrinsic and extrinsic job rewards. In general, the paper contributes to a greater understanding of inequalities in job rewards as-sociated with employee lexibilities.

Functional Flexibility and Job Rewards

Functional lexibility, as an alternative strategy to the hierarchical workplace system, irst attracted the attention of employers and employees during the 960s. “Total quality management,” “industrial democracy,” “team work,” “high performance work system,” were among the variations responding to global competition and the declining performance of the United States econ-omy (Simmons and Mares 985). Regardless of their labels, the arrangements were intended to foster employee organizational commitment, reduce turnover, transform adversarial labour/management relations, and channel workers’ knowledge toward productivity and eficiency (Halaby and Weakliem 989). Since then, two sets of theories — one that emphasizes positive consequences of lexibility (optimistic view) and one that challenges its consequences (pes-simistic view) — have been developed to explain functional lexibility and its association with job rewards.

1. Optimistic Views

Unlike Hirschhorn’s technological determinist view, Wright’s (2000: 964) theory of “positive class compromise” elaborates a neo-Marxist explanation for functional lexibility. In a democratic capitalist society, “class conlict is contained through real compromises, involving real concessions, rather than brute force.” The relations are sustained in signiicant ways through the “active consent” of people in the subordinate class. Contrary to the logic of traditional Marxists, workplace relations are no longer treated as a zero-sum game; rather, both employers and workers can improve their positions through various forms of active and mutual cooperation. “On the one hand, capitalists have interests in being able to unilaterally control the labor process . . . and on the other hand, they have interest in being able to reliably elicit cooperation, initiative, and responsibility from employees” (Wright 2000: 98). Wright adds that the more workers are involved in decision making, initiative, and cooperation (func-tional lexibility), the more job rewards they enjoy. Cappelli (999) calls the emerging workplace systems the “new deal” in which the lexibility of mar-ket-based mechanisms and solutions are increasingly substituted for the rigid-ity of the bureaucratic and hierarchical production system (see also, Belanger, Edwards, and Wright 2002).

The main explanatory factor in “post-hierarchical” theory is technology; in neo-Marxist theories, it is “class compromise.” “Flexible specialization” theory construes work lexibility by social, political, and technological condi-tions. The general premise is that technological paradigms require a social-pol-itical apparatus outside the irm to secure the necessary conditions for work-place lexibility. Vallas (999: 73) reviews at least three factors underlying the new conditions: internationalization of trade, the increasing demand for qual-ity goods and services through which “consumers express their distance from the ‘vulgar’ world of mass production,” and diffusion of information technol-ogy which provides opportunities for all production organizations, especially small irms, to produce diversiied quality goods. Under these conditions, both “large and small employers begin to converge on a new technological para -digm — lexible specialization — which provides a powerful yet lexible en-gine of growth that is optimally suited to the new economic conditions.” While these three theories explain functional lexibility differently, they all agree on its positive consequences. Functionally lexible jobs offer opportunities for ac-quiring multiple skills, participation in decision making, and teamwork, all of which are associated with higher job rewards for workers (Kalleberg 200; Edwards, Geary, and Sisson 2002), and beneits for owners (Wright, 2000).

2. Pessimistic Views

Contrary to the optimism of the previous theories, which suggest higher job rewards for functionally-lexible jobs, a few studies have discussed employee “exploitation.” They suggest that functional lexibility, while producing job rewards for some workers, is a new control device in the globalized econ-omy. Graham’s study (995) reveals that a teamwork arrangement served as a workplace control mechanism, rather than a method of enhancing employees’ autonomy. Baker’s (993) research in a small electronics company found that self-directed work teams imposed a “concertive control” system in which em-ployees internalized their obligations to managers, even to the extent of policing each other. Osterman (2000: 77), using 992 and 997 surveys of American establishments, comes to a conclusion more consistent with a pessimistic view. He states that high performance work organizations with functionally lexible jobs “have not delivered on the promise of mutual gains. . . . Hence, if anything, this check on the robustness of the results leads to even slightly more pessimis -tic conclusion.” The pessimis-tic perspective is that functional lexibility directs employees to collaborate in the intensiication of workload and an escalation of the pace of work without receiving signiicant beneits. Overall, these studies suggest that functional lexibility has intensiied workload and responsibilities, creating more job stress, rather than providing more job rewards.

Hypothesis 2: Consistent with the pessimistic perspective, and contrary to the argument of optimistic views, functionally lexible jobs should not offer signiicantly higher extrinsic and intrinsic rewards net of other factors, includ -ing workers’ characteristics.

Numerical Flexibility and Job Rewards

“buf-fer zone” to protect standard jobs during economic slack times (Kalleberg et al. 2000). Through the use of nonstandard arrangements, organizations have successfully implemented numerical lexibility; nonstandard workers, unlike standard employees, are easily “disposable” (Thomas 994). Nonstandard em-ployment provides organizations with lexible stafing options and cost reduc-tions. Davis-Blake and Uzzi (993: 95) note that externalization (nonstandard workers) of the workforce is important in understanding workplace inequal -ity because “it actually increases inequal-ity in distribution of rewards, which can have many important consequences, including lower productivity and in-creased conlict inside organizations.” Kalleberg et al. (2000: 273), using 995 Current Population Survey (CPS) data, conclude that “every nonstandard work arrangement we examined is more likely to be associated with bad job char-acteristics than [any] standard work arrangement.” Low earnings and a lack of health insurance and pension beneits characterize “bad jobs.” Finally, Barnett and Miner (992) argue that nonstandard workers may reduce the competition standard workers face for job rewards, especially promotion; entry of nonstan-dard employees into an organization has a “rivalry-elimination effect” which increases promotion chances for regular employees.

Hypothesis 3: Following this line of analysis, signiicant and positive cor -relations between job rewards and numerical lexibility are expected. That is, the average rewards associated with standard jobs are expected to be signii -cantly higher than the average rewards of nonstandard jobs net of other fac -tors, including workers’ characteristics.

Relationship between Functional and Numerical Flexibility

The preceding discussion on numerical lexibility and job rewards raises a ma-jor question: are the higher rewards associated with standard jobs the product of their higher functional lexibility, or their other characteristics, or both? This question highlights the signiicance of the relationship between functional and numerical lexibility. Most organizations in the United States have implement-ed both numerical and functional lexibility in the workplace. For example, Kalleberg (2003) shows that 36 percent of US establishments have used both functional and numerical lexibility using two or more criteria of functional lexibility (teamwork, multi-tasking, and performance incentives), whereas about half of US establishments have adopted both lexibilities, using at least one criterion of functional lexibility. Despite this, confusion and disagreement still exist as to the nature of the additive and interactive relationship between functional and numerical lexibility.

that internalization (development of standard jobs with functionally lexibility) and externalization (recruiting nonstandard workers) serve different, but com-plementary, functions in the workplace. Internalization enhances control and stability while externalization promotes lexibility and cost reduction. Thus, job rewards associated with standard jobs are high and more stable because of their higher functional lexibility, while externalization (nonstandard jobs) is associated with limited and unstable job rewards. Smith (994; 200) ad-dresses workplace inequality by contrasting “enabling” and “restrictive” ap-proaches. “Enabling” approaches upgrade standard jobs with more functional lexibility and higher job rewards within the established Internal Labour Mar-ket; “restrictive” approaches lead to “comparative degrading” by externaliz-ing the labour force (nonstandard jobs) with unstable and limited job rewards. These arguments strongly suggest that higher job rewards for standard jobs, if any, should be attributed to their higher functional lexibility. Following this argument:

Hypothesis 4: No signiicant regression coeficients between numerical lexibility and job rewards are expected, net of functional lexibility and back-ground variables, since higher rewards associated with functional lexibility would be under control.

Others argue that adopting functional lexibility is not limited only to the realm of standard jobs; rather, human resource mangers have implemented the strategy among both standard and nonstandard jobs. Appelbaum (987) notes that a majority of nonstandard workers no longer perform unskilled tasks; many are professionals and semi-professionals, such as nurses or accountants, suggesting that some nonstandard jobs enjoy higher degrees of functional lex-ibility and thereby job rewards. In other words, functional lexlex-ibility is not exclusively related to standard jobs and nonstandard job holders do not always suffer from lack of opportunities regarding autonomy, decision making, and teamwork, or lower job rewards. Therefore, the higher rewards associated with standard jobs should be attributed to characteristics other than their functional lexibility, such as the support of labour unions, government legislation (Oster-man 994; 2000), and/or implicit promises of long-term employment (Davis-Blake and Uzzi 993). Based on these arguments:

Hypothesis 5:Signiicant regression coeficients between numerical lex -ibility and job rewards are expected, net of functional lexibility and back-ground variables, since the discussion assumes higher rewards associated with standard jobs as the outcome of factors other than functional lexibility.

We ind that after controlling for the various indicators of human capital (e.g., educa-tion, autonomy or skill) . . . nonstandard jobs are still more likely to have bad conditions [low pay, no health insurance, and no pension beneits]. We believe that these result from a structural imbalance in the market capacities of employers and employees and differences in bargaining power.

Kalleberg et al. (997: 6, emphasis added) compare the quality of standard and nonstandard jobs, noting “that nonstandard workers, on average, receive lower wages than regular full time workers with similar personal characteristics and educational qualiications.” In simple terms, the same level of functional lex-ibility (multiple skills, autonomy, and teamwork) is compensated differently within standard and nonstandard jobs. This is similar to the “segmented labour market” thesis that workers’ human capital is rewarded differently within the “primary” versus “secondary” labour market (Beck et al. 978). Dickens and Lang (993) describe this as “unequal pay for equal human capital.” This sug-gests that the effect of functional lexibility on job rewards depends on the categories of numerical lexibility (functional lexibility is rewarded differ-ently within standard and nonstandard jobs). A unit of functional lexibility is rewarded signiicantly more within standard jobs than nonstandard ones. If this is the case:

Hypothesis 6: Signiicant correlations between the interaction of functional and numerical lexibility with job rewards are expected, net ofadditive effects of functional and structural lexibility as well as workers’ characteristics.

Data, Measures, and Methodology

The major source of data for this study is the 2002 General Social Survey (GSS). The data are the basic source for functional and numerical lexibility and their associations with job rewards.4 In addition to the 2002 GSS, Current

Population Survey (CPS) Supplements for 995, 997, 999, and 200 provide additional information on numerical lexibility and its association with three more job rewards — health insurance, pension, and median weekly income. Comparing and contrasting the results of two data sets (GSS and CPS) can ver-ify the validity of the indings and check the robustness of the conclusions (for more discussion on CPS see, for example, Hipple 998; DiNatale 200). The 2002 GSS includes hundreds of questions related directly to job characteristics of the respondents, including functional and numerical lexibility. The sample comprises 785 valid cases (the sample originally contained 2765 cases),

cluding nearly 30 percent nonstandard (alternative and part-time) employees and 70 percent standard (full-time regular) workers.

Unit of Analysis

This study is designed to explore individual consequences of employee lex-ibility, especially job rewards. Job rewards are structured in job positions and their signiicance depends on the perception of individual employees. There-fore, individual job holders and their jobs are assumed to be the appropriate unit of analysis. Davis-Blake and Uzzi (993) used both job and establish-ment as the units of analysis to explain the purpose of using temporary and independent contractors. Kalleberg (200) prefers a network, deined by the relationships among the organizations and subcontractors, as the appropriate unit of analysis for analyzing employee lexibility. This research argues that identiication of an appropriate unit of analysis depends on the aim(s) of a study; therefore, worker, jobs, establishment, organization, or network can all be useful units of analysis. An organization or a irm can be an appropriate unit of analysis to explore the policy or strategies of an organization on recruiting standard versus nonstandard employees. A network, as Kalleberg (200) sug-gested, can be an appropriate unit of analysis if the purpose of a study is to understand the structure and dynamic of workplace lexibility.

While a job holder is an appropriate unit of analysis for analyzing job re-wards (dependent variables), both functional and numerical lexibilities (two independent variables) are structural features of work organizations. This can be addressed by reducing the independent variable unit of analysis from an organizational lexibility to a respondents’ perception of workplace lexibil-ity. Functional lexibility is a novel work arrangement offering a systematic break with bureaucratic work structure, but its labour-related consequences are very similar to the traditional empowerment of workers through opportunities to acquire multiple skills, experience teamwork, and participate in decision making processes (“re-crafting America”).5 Social psychology theories of the workplace suggest it is the perception of workplace opportunities, rather than

5 Some may challenge using such measures on the grounds that these characteristics relect craft types of highly autonomous jobs rather than functional lexibility. There are three responses to this challenge. First, all jobs covered in this study are organ-izational — either government employees or private irm workers. Second, as men-tioned by Vallas (999), both large and small irms including craftsmen adopted a

the workplace itself, that affects workers’ responses toward workplace charac-teristics (Hall 994). Since this study examines the individual consequences of workplace lexibility, rather than lexibility itself, workers’ perceptions of lexibility become relevant.

Measurement and Methodology

The GSS data contain one question directly measuring numerical lexibility. This item taps into work arrangements at one’s main job, and contains the following categories: “Independent contractor/consultant/freelance worker” (3.8%); “on-call, work only when called to work” (2.3%); “paid by temporary agency” (0.8%); “work for contractor who provides workers/services” (2.4%); and “regular, permanent employee” (.7% part-time, 68.5% full-time, and a total of 80.2%). The answers have been regrouped into two categories — non-standard workers (the irst four categories plus part-time regular employment) and standard workers (the last category minus the part-time regular employ-ment). Nonstandard jobs are also occasionally divided into a few categories (independent contractors and the other nonstandard job holders) to reveal with-in group variation and allow comparison with standard jobs.6 Independent con -tractors, because of their self-determined work pace and autonomy (Rebitzer 995; Kalleberg 200) are growing faster than the other arrangements among professional and semi-professional jobs. In a national survey, more than 83 percent of independent contractors preferred to keep their jobs, rather than tak-ing a standard job (CPS 200). Their signiicantly higher degree of job auton-omy is associated with higher intrinsic job rewards, especially higher degrees of job satisfaction (Armstrong 97; Kashei 2004).

Functional lexibility has been measured by respondents’ perceptions of job characteristics attributed to functional lexibility. As discussed in the unit of analysis, functional lexibility is an organizational level dynamic but its tangible results are seen in workers’ attitudes and behaviours. Most scholars in the ield of organizational lexibility agree that functional lexibility pro-vides employees with more participation in decision making (decision-making lexibility), heavy reliance on teamwork (teamwork lexibility), and multiple skilled jobs (task lexibility) (e.g., Appelbaum and Batt 994; Kalleberg 200; Osterman 994; Smith 994; Wood 989; Zuboff 988). Therefore, this paper

uses those three sets of job characteristics to operationalize functional lex-ibility, relecting the degrees of functional lexibility implemented.The 2002 GSS data contain many items that tap into functional lexibility. After a careful theoretical examination, ten items were selected and subjected to exploratory factor analysis with oblique rotation, which assumes the resulting factors are correlated with one another.7 Three constructs were extracted. Four items, the

respondent “does numerous things on jobs,” “jobs allow R [Respondents] use of skills,” “opportunity to develop my ability,” and “job requires R to learn new things,” exhibited high loadings (0.63 or higher) on the “task lexibility” factor. Three items, “how often R was allowed to change schedule,” “R has lot of say in job,” and “a lot of freedom to decide how to do job” indicated high loadings (0.63 and higher) on the “decision-making lexibility” factor. The last three items, “R works as part of a team,” “how often R takes part in decisions,” and “how often R set the way things are done” showed high loadings (0.7 and higher) on the “teamwork lexibility” factor. These three factors, with dif-ferent labels, are congruent with the three dimensions of functional lexibility discussed by most previous studies (see, e.g., Belanger et al.’s reports [2002] on the emerging principles of lexible production organizations —”autonomy and discretion,” “decreased supervision along with increasing degrees of self-regulation” and “multi-disciplinary teams and horizontal coordination”).

The main method adopted for data analyses entailed several multiple re -gression equations. All assumptions required for adopting a multiple regres-sion analysis were conirmed.8 To explore the effects of numerical lexibility on job rewards, it was irst measured as a dummy variable (standard workers= and nonstandard workers=0). To contrast the standard workers with independ-ent contractors and the other nonstandard workers, two dummy variables were constructed with the standard workers as the reference group. Numerical lex-ibility here is a nominal independent variable with three categories (standard workers, independent contractors, and other nonstandard workers). Standard workers are chosen for the reference group since it has the highest frequency (Allison 999). Allison (999: 62) calls the coeficients “adjusted differen-ces in the means of dependent variables.” Therefore, each coeficient for the dummy variables relects a comparison between “standard workers” with “in-dependent contractors” or with “other nonstandard workers” (for more discus-sion, see the indings on numerical lexibility). Overall, seven dependent vari-7 In an exploratory factor analysis, it is the degree of correlations within subsets of

variables that determines variable clusters (measures of constructs). In a conformity factor analysis, on the other hand, the researcher speciies the clusters beforehand. This study followed the former to explore the variables of each cluster based on their correlations.

W

ork Flexibility and its Individual Consequences

353

Y1 Y2 Y3 Y4 Y5 Y6 Y7 X1 X2 X3 X4

Y1 1

Y2 0.273*** 1

Y3 -0.034 0.90*** 1

Y4 -0.07*** 0.267*** 0.96*** 1

Y5 -0.052** 0.082*** 0.074*** 0.286*** 1 Y6 -0.075*** 0.265*** 0.280*** 0.253*** 0.08*** 1

Y7 -0.026 0.240*** 0.117*** 0.0367*** 0.9*** 0.201*** 1

X1 0.88*** 0.272*** 0.262*** 0.474*** 0.313*** 0.344*** 0.260*** 1

X2 0.80*** 0.266*** 0.95*** 0.447*** 0.329*** 0.341*** 0.232*** 0.796*** 1

X3 0.52*** 0.79*** 0.66*** 0.245*** 0.25*** 0.265*** 0.177*** 0.680*** 0.307*** 1

X4 0.035*** 0.147*** 0.244*** 0.348*** 0.243*** 0.54*** 0.174*** 0.755*** 0.455*** 0.229*** 1

Mean 10.07 2.07 2.37 .67 2.87 2.45 .68 6.62 7.03 6.52 8.93

S.D. 3.053 .096 0.850 0.847 0.837 1.047 0.877 4.93 2.250 2.68 2.214 * P <0.05, ** P <0.0, *** P <0.00

Job rewards:Y. Respondents’ income; Y2. Fringe beneits; Y3. Likelihood of bonus or pay increase;

Y4. Job Satisfaction in general;Y5. Satisfaction comes from work; Y6. Chances for promotion; Y7. Job security

ables, measuring both intrinsic and extrinsic job rewards have been analyzed, including the employees’ average income, fringe beneits, likelihood of bonus or pay increase, job satisfaction, promotion, and job security. The control vari-ables include, but are not limited to, the respondents’ characteristics, such as age, gender, race, and education.

Findings

Functional Flexibility and Job Rewards

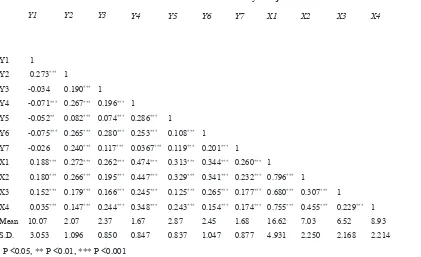

Table shows the zero-order correlations between the measures of total func-tional lexibility and its three components (task lexibility, teamwork lexibil-ity, decision-making lexibility), with seven measures of intrinsic and extrinsic job rewards. All the correlations are signiicant, suggesting that employees with higher functional lexibility enjoy signiicantly more job rewards, both intrinsic (job satisfaction, job security, and opportunity for promotion) and ex-trinsic (income and fringe beneits). Functional lexibility also signiicantly increases the likelihood of pay and bonuses, which are the major factors affect-ing employees’ organizational commitment (Kashei 2004). Finally, functional lexibility and the measure of “satisfaction comes from work” are signiicantly correlated, indicating that functionally lexible jobs, unlike routinized and stan-dardized traditional jobs, make the jobs desirable by providing opportunities for multiple skills, decision making, and teamwork.

Table 2. Standardized regression coeficients (β) for numerical lexibility

Y1 Y2 Y3 Y4 Y5 Y6 Y7

Independent Variable

Total Functional

Flexibility 0.100

*** 0.249*** 0.275*** 0.355*** 0.273*** 0.46*** 0.299***

Control Variables

Education 0.53*** 0.072*** 0.05** 0.030 0.070** 0.063 0.045

Age 0.110*** 0.006 0.076** 0.85*** 0.063** -0.75*** -0.28***

Gender 0.06*** 0.017 0.06 -0.042* 0.023 0.022 -0.049*

Race -0.027 -0.008 -0.034 0.022 -0.033 0.09 0.017 Part-full time 0.453*** 0.171*** 0.014 0.059** 0.043* 0.044* 0.065*

Occupational Prestige ——— —— —— —— —— 0.001 0.047 Income (log) —— —— —— —— —— 0.025 0.06* Fringe Beneits —— —— —— —— —— 0.69*** 0.003

R-Squared 0.292*** 0.113*** 0.078** 0.62*** 0.078*** 0.226*** 0.9***

N 1407 579 577 562 583 583 397

* P <0.05, ** P <0.0, *** P <0.00

Job rewards: Y. Respondents’ income; Y2. Fringe beneits

Y3. Likelihood of bonus or pay increase; Y4. Job Satisfaction in general Y5. Satisfaction comes from work; Y6. Chances for promotion; Y7. Job security

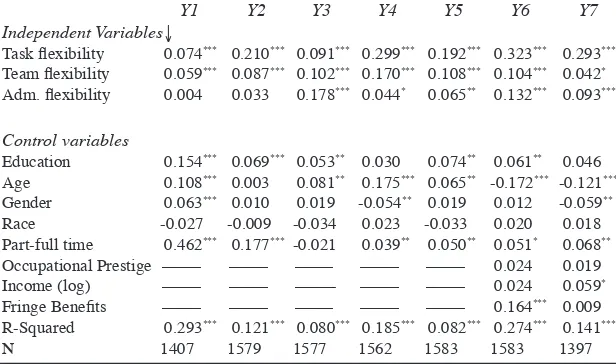

Table 3. Standardized regression coeficients (β) for components of functional

lexibility

Y1 Y2 Y3 Y4 Y5 Y6 Y7

Independent Variables↓

Task lexibility 0.074*** 0.210*** 0.09*** 0.299*** 0.92*** 0.323*** 0.293***

Team lexibility 0.059*** 0.087*** 0.102*** 0.170*** 0.08*** 0.104*** 0.042*

Adm. lexibility 0.004 0.033 0.78*** 0.044* 0.065** 0.132*** 0.093***

Control variables

Education 0.54*** 0.069*** 0.053** 0.030 0.074** 0.06** 0.046

Age 0.08*** 0.003 0.08** 0.75*** 0.065** -0.72*** -0.2***

Gender 0.063*** 0.010 0.09 -0.054** 0.09 0.012 -0.059**

Race -0.027 -0.009 -0.034 0.023 -0.033 0.020 0.08 Part-full time 0.462*** 0.177*** -0.02 0.039** 0.050** 0.05* 0.068**

Occupational Prestige ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— 0.024 0.09 Income (log) ——— ——— ———- ——— ——— 0.024 0.059*

Fringe Beneits ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— 0.64*** 0.009

R-Squared 0.293*** 0.121*** 0.080*** 0.85*** 0.082*** 0.274*** 0.141***

N 1407 579 577 562 583 583 397

* P <0.05, ** P <0.0, *** P <0.00

Job rewards: Y. Respondents’ income ;Y2. Fringe beneits;

Y3. Likelihood of bonus or pay increase;Y4. Job Satisfaction in general

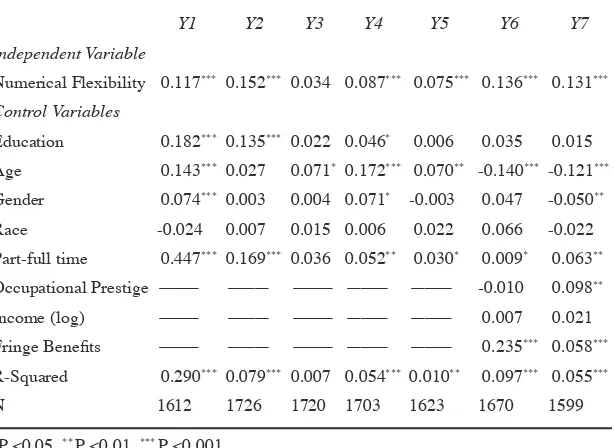

Numerical Flexibility and Job Rewards (GSS Data)

Table 4 presents job rewards for standard and nonstandard jobs. The average income, fringe beneits, job security, and chance for promotion for standard jobs are signiicantly higher than nonstandard jobs. This is consistent with the theory that job holders in standard jobs enjoy signiicantly more extrin-sic rewards as well as some intrinextrin-sic rewards. However, when the average scores for “job satisfaction” and “satisfaction comes from job” are contrasted for standard and nonstandard jobs, the indings do not support the theoretical discussions. Unexpectedly, for nonstandard workers, the average scores for both variables are signiicantly higher than the corresponding averages of stan-dard workers, suggesting that nonstanstan-dard workers express signiicantly more “job satisfaction” and “satisfaction comes from job” than standard workers. To justify the inding, nonstandard workers were subdivided into independent contractors and the other nonstandard ones, and then contrasted with standard workers. The second panel in Table 4 displays the indings and reveals that it is, in fact, “independent contractors” that enjoy a signiicantly higher degree of “job satisfaction” and “satisfaction comes from work” than the other groups (Tukey’s test in GLM used to test the signiicance of differences).

The indings suggest that independent contractors, despite having nonstan-dard jobs, display more job satisfaction and believe their jobs are a major source of satisfaction, compared with the other groups (see also Kalleberg 2000). This is not unusual, considering the labour market is witnessing a growing number of highly educated employees who prefer work as independent contractors, as illustrated by Silicon Valley employees (Carnoy et al. 997; DiTomaso 200; Kalleberg 2000). The result is also congruent with the inding that 83.4 percent of independent contractors prefer their employment arrangement, contrasted with 49. percent for on-call workers, and 44.5 percent for temporary help agency workers (CPS Supplement 200). Independent contractors are not em-ployees in traditional terms, but self-employed workers whose workplace is self-determined (Rebitzer 995; Kalleberg 2000). Further analysis of independ-ent contractors reveals that their average task lexibility and decision-making lexibility are signiicantly higher than the corresponding averages for standard and the other nonstandard workers (3.65 versus 2.97 and 2.5 for task lex-ibility, and 0.60 versus 8.66 and 8.06 for decision-making lexibility). Perhaps the autonomous and self-regulatory nature of their jobs does not demand their involvement in teamwork (Benoit 2002). Therefore, while their jobs offer both better opportunities on task lexibility and decision-making lexibility, their average team lexibility is signiicantly lower than the other groups (7.8 con-trasted with 8.7 for the other nonstandard and 8.69 for standard workers).

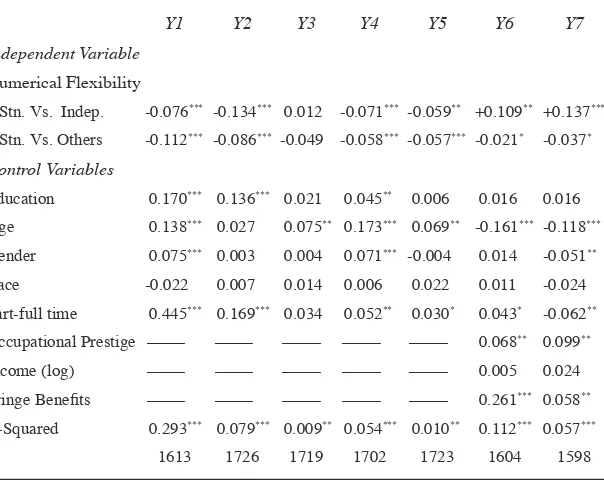

equations measuring the effect of numerical lexibility on seven different in-trinsic and exin-trinsic job rewards, with controls for workers’ characteristics and several other variables. All the coeficients (β), except for “likelihood of bonus and pay increase,” are statistically signiicant, suggesting that after control-ling for the effects of workers’ characteristics on job rewards, numerical lex-ibility still signiicantly affects the variations of both intrinsic and extrinsic job rewards. Further analyses, contrasting standard workers with independents contractors and other nonstandard workers, are revealed in Table 6. This table shows most of the coeficients are negative, but statistically signiicant. A few interpretations clarify the inding. The coeficient “-0.076” means, on aver-age, that independent contractors’ income is 0.076 unit lower than “standard workers,” the reference group; “-0.34” means “other nonstandard” workers make, on average, 0.34 unit lower fringe beneits than “standard workers”; “+0.02” means, on average, “independent contractors” display a “0.02” unit higher job satisfaction than “standard workers.” Overall, independent contract-ors show signiicantly higher job satisfaction and higher level of “satisfaction Table 4. Average job rewards of numerical lexibility

Individual outcomes Standard Nonstandard F-score

Y= Respondent income .6 8.76 30.98***

Y2= Fringe beneits are good 3.11 2.58 23.96*** Y3= Likely to get a bonus or pay increase .62 .68 1.37 Y4= Chance for promotion 2.63 2.36 2576***

Y5= Job security 3.35 3.22 5.72**

Y6= Job satisfaction in general 3.32 3.41 5.67** Y7= Satisfaction come from work 2.11 2.35 30. 08***

Other

Individual outcomes Standard Contractor Nonstandard F-score

Y= Respondent income .6 9.77 7.92 90.27***

Y2= Fringe beneits are good 3.13 2.57 2.49 62.43*** Y3= Likely to get a bonus or pay… .63 1.71 .59 .38 Y4= Chance for promotion 2.63 2.28 2.42 4.06*** Y5= Job security 3.35 3.25 3.12 3.23* Y6= Job satisfaction in general 3.32 3.53 3.31 8.35*** Y7= Satisfaction comes from work 2.11 2.41 2.03 6.84***

comes from jobs” than standard workers. However, the other job rewards for standard workers are signiicantly higher than for independent contractors. As the table shows, the average job rewards for “other nonstandard” workers are signiicantly lower than the job rewards of standard workers. The indings are mostly consistent with the theoretical discussions and partially substantiate the third hypothesis that standard jobs offer signiicantly more opportunities for various extrinsic and intrinsic rewards, except job satisfaction and “satisfaction comes from work.” After breaking down nonstandard jobs into “independent contractors” and “other nonstandard jobs,” the indings become more reason-able and meaningful. As predicted in the theoretical discussion, independent contractors, because they have a higher degree of autonomy than the other nonstandard workers, display signiicantly more job satisfaction than the other groups, including the standard workers.

Numerical Flexibility and Job Rewards (CPS Data)

As a supplemental analysis, Table 7 provides additional information on em-ployees’ distribution on various standard and nonstandard jobs from 995 to 200, as well as median income and the percentage of workers who have health Table 5. Standardized regression coeficients (β) for numerical lexibility

Y1 Y2 Y3 Y4 Y5 Y6 Y7

Independent Variable

Numerical Flexibility 0.117*** 0.52*** 0.034 0.087*** 0.075*** 0.36*** 0.131***

Control Variables

Education 0.82*** 0.35*** 0.022 0.046* 0.006 0.035 0.05 Age 0.143*** 0.027 0.071* 0.172*** 0.070** -0.40*** -0.2*** Gender 0.074*** 0.003 0.004 0.071* -0.003 0.047 -0.050** Race -0.024 0.007 0.05 0.006 0.022 0.066 -0.022 Part-full time 0.447*** 0.69*** 0.036 0.052** 0.030* 0.009* 0.063** Occupational Prestige ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— -0.00 0.098**

Income (log) ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— 0.007 0.021

Fringe Beneits ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— 0.235*** 0.058*** R-Squared 0.290*** 0.079*** 0.007 0.054*** 0.010** 0.097*** 0.055***

N 62 726 1720 1703 623 670 599

* P <0.05, ** P <0.0, *** P <0.00

Job rewards: Y. Respondents’ income; Y2. Fringe beneits

insurance and a pension. The top panel in the table shows that the percentage of standard employees (full time regular) increased slightly from 73.6 percent in 995 to 75.3 percent in 200, while the percentage of nonstandard workers declined slightly from 26.4 percent in 995 to 24.7 percent in 200. Despite the changes, one quarter of US employees remained nonstandard workers in 200. The data seem inconsistent with the argument that globalization has brought more nonstandard jobs (alternative, contingent, and part-time employees) to the workplace in the United States. The indings only relect the percentage of alternative employment from 995 to 200. It cannot be generalized to pre-vious years or decades. The percentage of part-time jobs, the major part of alternative employment, increased from 3 percent in 957 to 9 percent in 993 (Tilly 996) and 22.8 percent in 20039 (BLS, Table 5, 2003). The

per-9 The labour force for 2003includes all 5 years and older people (CPS Supplement, 2003; employee’s status by percentage of full and part-time).

Table 6. Standardized regression coeficients (β) for numerical lexibility

Y1 Y2 Y3 Y4 Y5 Y6 Y7

Independent Variable

Numerical Flexibility

† Stn. Vs. Indep. -0.076*** -0.34*** 0.012 -0.07*** -0.059** +0.09** +0.137***

† Stn. Vs. Others -0.2*** -0.086*** -0.049 -0.058*** -0.057*** -0.02* -0.037*

Control Variables

Education 0.170*** 0.36*** 0.021 0.045** 0.006 0.06 0.06

Age 0.38*** 0.027 0.075** 0.173*** 0.069** -0.6*** -0.8***

Gender 0.075*** 0.003 0.004 0.071*** -0.004 0.014 -0.05**

Race -0.022 0.007 0.014 0.006 0.022 0.011 -0.024 Part-full time 0.445*** 0.69*** 0.034 0.052** 0.030* 0.043* -0.062**

Occupational Prestige ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— 0.068** 0.099** Income (log) ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— 0.005 0.024 Fringe Beneits ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— 0.26*** 0.058**

R-Squared 0.293*** 0.079*** 0.009** 0.054*** 0.010** 0.112*** 0.057***

N 63 726 79 1702 1723 604 598

† = Standard workers contrasted with independent contractors and other nonstandard employees.

* P <0.05, ** P <0.0, *** P <0.00

Job rewards: Y. Respondents’ income; Y2. Fringe beneits

centage of temporary help agencies’ employees increased from 0.3 percent in 972 to nearly 2.5 percent in 998 (Kalleberg 2000). The CPS data relect the change of nonstandard jobs for a shorter period of time. The transformation of nonstandard jobs, especially part-time, during the 970s and 980s was sub-stantially different from the 990s, a time of economic prosperity and a lower unemployment rate.

The second panel in Table 7 shows the distribution of job rewards (health care insurance, pension, and median weekly income) for standard and nonstan-dard workers in 999. The table shows that 84.8 percent of stannonstan-dard workers were covered by health insurance, which is signiicantly higher than the per-centages for nonstandard groups in 999. Among the nonstandard employees, temporary help agency workers have the lowest (41.0 percent) coverage and workers provided by contract irms have the highest (79.9 percent) health insur-Table 7. Distribution of workers along with their beneits across work

arrangements

1995 1997 1999 2001†

Total: (In thousands) 23,208 26,742 3,494 34,605

(Percentage) 100 100 100 100

Standard (Full-time regular) 73.6 74.2 75. 75.3

Nonstandard employees:* 26.4 25.8 24.9 24.7

Part time regular employee 6.5 5.9 5.5 5.3

Alternative employees:

a. Independent contractors 6.7 6.7 6.3 6.4

b. On-call workers 1.7 .6 .5 .6

c. Temp. Agency workers 1.0 1.0 0.9 0.9

d. Workers…contract irms 0.5 0.6 0.6 0.5

Beneits for standard and non-standard job-holders (1999)

Total (1000) Health

Insurance Overall pension

Weekly Earning††

Standard (Full time regular) 98,766 84.8 58.2 540 Non-Standard employees: 33,002 72.6 14.7 277 a. Part-time regular employees 20,766 74.3 6.8 57

Alternative Employees 2,236 69.6 11.3 480

a. Independent contractors 8,247 73.3 2.8 532 b. On-call workers 2,032 67.3 29.0 293 c. Temp. Agency workers ,88 41.0 .8 309 d. Workers…contract irms 769 79.9 53.9 679

† = Source: Calculated from “CPS Supplements”—995, 997, 999, 200.

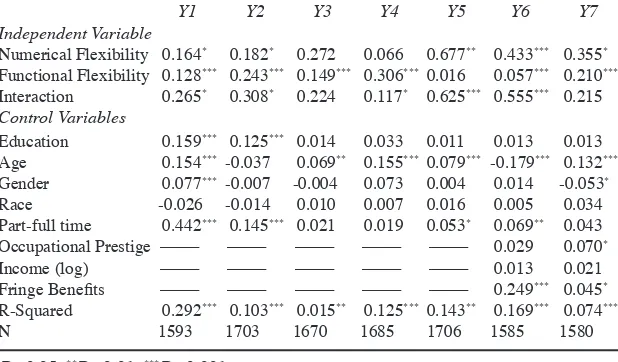

ance coverage. The same is true for pension beneits: 58.2 percent of standard job holders have pensions, contrasted with signiicantly lower rates for all other nonstandard workers. Among the nonstandard workers, workers provided by contract irms have the best pension beneits, with 53.9 percent, and independ-ent contractors have the worst — only 2.8 percindepend-ent of such workers are covered. Finally, while the median weekly income for standard workers is signiicantly higher than the average of all nonstandard job holders ($540 vs. $277), the me-dian income for “workers provided by contract irms” is higher than all other groups, including standard workers. It is notable that “workers provided by con-tract irms” account for only 2 percent of all nonstandard jobs. Overall, the CPS data provide information on numerical lexibility and additional job rewards and, more importantly, support the robustness of conclusions taken from GSS data that standard workers, on average, enjoy more job rewards than nonstan-dard job holders, without ignoring the variation within the nonstannonstan-dard jobs. Additive and Interactive Effects of Employee Flexibility on Job Rewards Table 8 displays the standardized regression coeficients (β) for both additive and interactive effects of functional and numerical lexibilities on job rewards, with controls for several other variables.

All three coeficients relecting the additive and interactive effects of num-erical and functional lexibility on respondents’ income, fringe beneit, and job satisfaction are statistically signiicant. They suggest that each additional unit of functional lexibility is associated with an increase of 0.28 units on income, 0.243 units on fringe beneits, and 0.057 units on job satisfaction for nonstan-dard job holders and 0.265 additional units on income, 0.308 additional units on fringe beneit, and .555 additional units on job satisfaction for standard job holders. In other words, each additional unit of functional lexibility increases 0.393 (0.28+0.265) units on income, 0.55 (0.243+0.308) units on fringe beneits, and 0.602 (0.057+0.5550 units on job satisfaction for standard job holders.10 The signiicance of interactive coeficients suggests that functional

lexibility not only directly (additive) affects income, fringe beneits, and job satisfaction but the degree of its effect also depends on the context (standard versus nonstandard jobs) within which it operates. Within standard jobs, func-tional lexibility has been compensated with signiicantly higher job rewards than within nonstandard jobs. The indings substantiate the sixth hypothesis

10 The interactive effect can also be interpreted with respect to job characteristics other

that a signiicant interactive effect exists between functional and numerical lexibility, net of their additive effects and the other factors.

Among the other job rewards, “job security” displays signiicant coefi-cients with numerical lexibility and with the interactive factor, while the addi-tive effect of functional lexibility becomes nonsigniicant. The coeficients suggest that functional lexibility produces additional job security for standard job holders while having no signiicant effects on job security of nonstandard workers, since standard jobs maintain structural characteristics that make their functional lexibility signiicantly more effective on their job security. Unlike “job security,” “chances for promotion” reveals signiicant coeficients with additive and interactive effects of functional lexibility while the additive effect of numerical lexibility becomes nonsigniicant. Therefore, unlike job security, functional lexibility becomes very signiicant not only in creating promotion opportunity (0.306) for nonstandard job holders but also 0.7 additional units for standard job holders. Finally, the other two job rewards, “likelihood of bonus or pay increase” and “satisfaction comes from work” display no signii-cant coeficients with the interactive factors while they have signiisignii-cant regres-sion coeficients with functional and/or numerical lexibilities. Functionally lexible jobs create signiicantly better opportunities to use multiple skills, par-ticipate in teamwork, and decision making, thereby improving workers’ “satis-Table 8. Standardized regression coeficients (β) for numerical and functional

lexibility

Y1 Y2 Y3 Y4 Y5 Y6 Y7

Independent Variable

Numerical Flexibility 0.64* 0.82* 0.272 0.066 0.677** 0.433*** 0.355* Functional Flexibility 0.28*** 0.243*** 0.49*** 0.306*** 0.06 0.057*** 0.210*** Interaction 0.265* 0.308* 0.224 0.117* 0.625*** 0.555*** 0.25

Control Variables

Education 0.59*** 0.25*** 0.014 0.033 0.011 0.013 0.013 Age 0.54*** -0.037 0.069** 0.55*** 0.079*** -0.79*** 0.132*** Gender 0.077*** -0.007 -0.004 0.073 0.004 0.014 -0.053* Race -0.026 -0.04 0.010 0.007 0.06 0.005 0.034 Part-full time 0.442*** 0.45*** 0.021 0.09 0.053* 0.069** 0.043 Occupational Prestige ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— 0.029 0.070*

Income (log) ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— 0.013 0.021

Fringe Beneits ——— ——— ——— ——— ——— 0.249*** 0.045* R-Squared 0.292*** 0.103*** 0.05** 0.25*** 0.143** 0.69*** 0.074***

N 593 1703 670 685 706 585 580

* P <0.05, ** P <0.0, *** P <0.00

Job rewards: Y. Respondents’ income; Y2. Fringe beneits

faction comes from jobs.” The same is true for attitudes relecting “likelihood of bonus or pay increase.”

Overall, table 8 shows that six out of seven coeficients measuring the ef-fects of functional lexibility on job rewards are statistically signiicant, net of numerical lexibility, interactive factors, and the background variables. This highlights the importance of functional lexibility in explaining the variation of intrinsic and extrinsic job rewards. Furthermore, ive out of seven job re-wards reveal signiicant coeficients with numerical lexibility when functional lexibility and its interaction, as well as the background variables, are kept constant. This also underscores the idea that organizational characteristics af-fecting job rewards are not limited to their higher functional lexibility. Rather, they maintain characteristics otherthan functional lexibility that signiicantly affect the variation of extrinsic and intrinsic rewards. Finally, keeping the addi-tive effects of lexibilities and the background factors under control, ive out of seven interactive coeficients still remain statistically signiicant. This em-phasizes the issue of “unequal rewards” for equal functional lexibility within two types of work arrangements —standard versus nonstandard jobs, which is very similar to the notion that doing the same tasks within dual labour markets (primary vs. secondary) produces unequal rewards.

Summary and Conclusions

job rewards, their interactive effect on variation of job rewards is also notable. The signiicance of the interactive effect on job rewards suggests that standard workers gain higher amounts of job rewards for every additional unit of func-tional lexibility than workers in nonstandard jobs.

The indings have signiicant theoretical implications. First, classiication of jobs as standard versus nonstandard (measure of numerical lexibility) is useful but weak. Nonstandard jobs are a heterogeneous group with signiicant variation in their functional lexibility and their job rewards. Further studies, analyzing rewards inequality within standard workers — service versus manu-facturing, for example — are useful and help us measure and categorize num-erical lexibility in more eficient ways. Osterman (2006) reported signiicant-ly higher average income for workers in “high performance” manufacturing, contrasted with nonmanufacturing, organizations. Browning and Singelmann (975: 240) noted “work in service industries is more lexible than in good-producing industries” for a number of reasons, including the smaller establish-ment size in services and higher work “standardization” in manufacturing.

The existence of job characteristics other than functional lexibility that produce higher rewards for standard jobs has not been systematically theor-ized. Further studies need to identify these factors (government protection legislation, labour unions, etc.) and systematically explore their signiicance on distribution of job rewards. Finally, this research found that functional lex-ibility produces additional job rewards, depending on the context (standard versus nonstandard jobs) within which it operates. This interactive effect has a very limited theoretical basis. It may be the result of the stronger bargain -ing power of labour unions among standard workers or the outcome of higher values attached to skills and human capital among standard workers, or some-thing else. The interactive effects of employee lexibility may be explained by further studies, which will theoretically contextualize our knowledge of inequality in job rewards.

can widen rewards inequality and polarize workers within a irm or production network (Kalleberg 200; 2003; Kashei 994). It is prudent for human resour-ces strategists and policymakers to consider both forms of conlicts when they are implementing numerical lexibility in the workplace. Finally, the growing tendency to adopt numerical lexibility may result, theoretically at least, in higher rates of poverty and economic inequality at the societal level, as well as causing lower morale, declining productivity, and lower organizational com-mitment in the workplace.

References

Allison, Paul

999 Multiple Regression: A Primer. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press. Appelbaum, Eileen

2002 The impacts of new forms of work organization on workers. In G. Murray, J. Belanger, A. Giles, and P. Lapointe, eds., Work and Employment Relations in the High Performance Workplace. London: Continuum.

987 Restructuring work: temporary, part-time, and at-home employment. In Heidi Hartmann, ed., Computer Chips and Paper Clips: Technology and Women’s Em -ployment. Vol., Washington, D.C.: National Academic Press.

Appelbaum, Eileen and R. Batt

994 The New American Workplace: Transforming Work Systems in the United States.

Ithaca, NY: ILR Press. Armstrong, B. Thomas

97 Job content and context factors related to satisfaction for different occupational levels. Journal of Applied Psychology 55: 57–65.

Barker, Kathleen and Kathleen Christensen

998 Contingent Work: American Employment Relations in Transition. Ithaca, NY: Cornel University Press.

Baker, James

993 Tightening the iron cage: concertive control in self managing teams. Adminis-trative Science Quarterly 38: 262–28.

Batt, R. and E. Appelbaum

995 Worker participation in diverse settings: does the form affect the outcome, and if so, who beneits. British Journal of Industrial Relations 33 (3): 33–78. Beck, E., P. Horan; and C. Tolbert

978 Stratiication in dual economy: a structural model of earning determination.

American Sociological Review 43: 704–720. Barnett, William and Anne Miner

992 Standing on the shoulders of others: career interdependence in job mobility.

Belanger, Paul, P.A. Lapointe, and B. Levsque

2002 Workplace innovation and the role of institutions. In G. Murray, J. Belanger, A. Giles, and P. Lapointe, eds., Work and Employment Relations in the High Performance Workplace. London: Continuum.

Belanger, Jacques, P. Edwards, and M. Wright

2002 Commitment at work and independence from management. Work and Occupa-tions 30: 234–252.

Belanger, Jacques, A. Giles, and G. Murray

2002 Toward a new production model: potentialities, tensions, and contradictions. In G. Murray, J. Belanger, A. Giles, and P. Lapointe, eds., Work and Employment Relations in the High Performance Workplace. London: Continuum.

Benoit, Delage

2002 A portrait of the self-employed. Work Life Report 4 (): 6–7.

Blank, Rebecca M.

998 Contingent work in a changing labour market. In R. Freeman and P. Gottshalk, eds., Generating Jobs: How to Increase Demand for Low-Skilled Workers. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Press.

Bluestone, Barry

970 The tripartite economy: labor market and the working poor. Poverty and Human Resources Abstract 5: 5–35.

Browning, Harley and J. Singelmann

975 Emergence of a Service Society: Demographic and Sociological Aspects of the Sectoral Transformation of the Labor Force in the U.S.A. Austin, Texas: Popu-lation Research Center, University of Texas.

Cappelli, Peter

999 The New Deal at Work. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Carnoy, Martin, M. Castells, and C. Brenner

997 Labor markets and employment practices in the age of lexibility: a case study of Silicon Valley. International Labour Review 36(): 27–48.

Christensen. K.

99 The two-tiered workforce in US corporations. In B. Peter Doeringer, Kath-leen Christensen, Patricia M. Flynn, Douglas T. Hall, Harry C. Katz, Jeffrey H. Keefe, Christopher J. Ruhm, Andrew M. Sum, and Michael Useem., eds.,

Turbulence in the American Workplace. New York: Oxford Press. Davis-Blake, Alison and Brian Uzzi

993 Determinants of employment externalization: a study of temporary workers and independent contractors. Administrative Science Quarterly 38:95–223. Davis, James and Tom Smith

992 The NORC General Social Survey: A User's Guide. Newbury Park: Sage Pub-lication.

Dickens, William and K. Lang

DiNatale, Marisa

2001 Characteristics of and preference for alternative work arrangement. Monthly Labor Review March 200: 28–48.

DiTomaso, Nancy

200 The loose coupling of jobs: the subcontracting of everyone?” In I. Berg and A. Kalleberg, eds., Source Book on Labor Markets: Evolving Structures and Poli -cies. New York: Klumer/Plenum.

Doeringer, Peter. B. and Michael Piore

97 Internal Labor Market and Manpower Analysis. Lexington: Mass.: D.C. Health.

Edwards, Paul, John Geary, and K. Sisson

2002 New forms of work organization in the workplace: transformative, exploitative, or limited and controlled? In G. Murray, J. Belanger, A. Giles, and P. Lapointe, eds., Work and Employment Relations in the High Performance Workplace. London: Continuum.

Graham, Laurie

995 On the Line at Subaru-Isuzu. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press. Halaby, Charles and D. Weakliem

989 Work control and commitment to the irm. American Journal of Sociology 95: 549–59.

Hall, Richard

994 Sociology of Work. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press. Harrison, Bennett

972 Education, Training, and the Urban Ghetto. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hipple, Steven

998 Contingent work: results from the second survey. Monthly Labor Review Nov.: 22–35.

Hirschhorn, Larry

984 Beyond Mechanization. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Houseman, Susan. N.

200 Why employers use lexible stafing arrangement: evidence from an establish-ment survey. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55(): 49–79.

Houseman, Susan, A. Kalleberg, and G. Erickcek

2003 The role of temporary agency employment in tight labor markets. Industrial and Labor Relation Review 57: 05–27

Kalleberg, Arne, J. Reynolds, and P. Marsden

2003 Externalizing employment: lexible stafing arrangements in US organizations. Social Science Research 32: 525–552.

Kalleberg, Arne, B. Reskin, E. Rasaell, and K. Hudson

Kalleberg, Arne, E. Rasaell, K. Hudson, D. Webster, B. Reskin, N. Cassirer, and E. Appelbaum

997 Nonstandard Work, Substandard Jobs: Flexible Work Arrangement in the US. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

Kalleberg Arne

2003 Flexible irms and labor market segmentation: effects of workplace restructur-ing on jobs and work. Work and Occupations 30(2): 54–75.

200 Organizing lexibility: the lexible irm in a new century. British Journal of In -dustrial Relations 39(4): 479–504

2000 Nonstandard employment relations: part-time, temporary, and contract work.

Annual Review of Sociology 26: 34–365. Kashei, Mahmoud

2004 Structural features of jobs and organizational attachment: explaining variation in organizational attachment between black and white employees. Journal of Black Studies 34(5): 702–78.

994 Occupational transformation in the United States economy 970–990: examin-ing job polarization. Sociological Focus 26: 277–299.

McGovern, Patrick, D. Smeaton, and S. Hill

2004 Bad jobs in Britain: nonstandard employment and job quality. Work and Oc-cupations 3: 225–249.

Olsen, Karen and Arne Kalleberg

2004 Non-standard work in two different employment regimes: Norway and the United States. Work, Employment, and Society 8(2): 32–348.

Osterman, Paul

2006 The wage effects of high performance work organization in manufacturing. In -dustrial and Labor Relations Review 59(2): 87–205.

2000 Work organization in an age of restructuring. Industrial and Labor Relation Review 53: 79–96.

999 Securing Prosperity. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

994 How common is workplace transformation and who adopts it? Industrial and Labor Relation Review 47: 73–88.

988 Employment Futures: Reorganization, Dislocation, and Public Policy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rebitzer, James B.

995 Job safety and contract workers in the petrochemical industry. Industrial Rela -tions 34(): 40–57.

Simmons, John and William Mares

985 Working Together: Employee Participation in Action. New York: New York University Press.

Smith, Vicki

200 Teamwork vs. tempwork: managers and the dualisms of workplace restructur-ing. In Daniel Cornield, K. Campbell, and H. McCammon, eds., Working in Restructured Workplaces. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Thomas, Robert. J.

994 What Machines Can’t Do: Politics and Technology in the Industrial Enterprise. Berkeley: University of California Press

Tilly, Chris

996 Half a Job: Bad and Good Part-time Jobs in a Changing Labor Market. Phila-delphia: Temple University Press.

U.S. Census Bureau

2002 Current Population Survey: Contingent Work Supplement. Washington D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

999 Current Population Survey: Contingent Work Supplement. Washington D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

997 Current Population Survey: Contingent Work Supplement. Washington D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

995 Current Population Survey: Contingent Work Supplement. Washington D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.

Vallas, Steven

999 Rethinking post-Fordism: the meaning of workplace lexibility. Sociological Theory 68: 68–02.

Wood, Stephen

989 The transformation of work? Pp. –43 in S. Wood, ed., TheTransformation of Work? Skill, Flexibility, and the Labour Process. London: Unwin Hyman. Wright, Eric Olin

2000 Working class power, capitalist-class interests, and class compromise. American Journal of Sociology 05: 957–002.

Zuboff, Shoshana