LOSS OF AGRICULTURAL LEXIS IN CAKAP KARO

A Thesis

Submitted to the English Applied Linguistics Postgraduate Program, In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the

Degree of Magister Humaniora

By:

INGRID GIBRETTA KHAIRANI GINTING

Register Number: 8136111034

ENGLISH APPLIED LINGUISTICS STUDY PROGRAM

POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL

ABSTRACT

Gibretta, I. NIM: 8136111034. Loss of Agricultural Lexis in Cakap Karo. A Thesis. English Applied Linguistics. Study Program: Postgraduate School. State University of Medan, 2015.

ABSTRAK

Gibretta, I. NIM: 8136111034, Leksikal Agrikultural yang Hilang dalam Cakap Karo, Tesis Program Studi Linguistik Terapan Bahasa Inggris, Pascasarjana, Universitas Negeri Medan, 2015.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

A great thank to Heavenly Father Jesus Christ for blessing and protection that have been continously poured to the writer in the process of completing her studies and this piece of academic masterpiece. The last of the prophets and upon her messengers and her families, and whoever follows below have given her invaluable help, support, suggestions motivation, encouragements during her study at the English Applied Linguistics Study Program, Postgraduate School State University of Medan.

In the process of completing this thesis, there are many people who have assisted and suggested the materials to be impossible to name all at some deserve the honor to be noted.

Firstly, the writer would like to express her gratitude to Professor. Dr. Busmin Gurning, M.Pd., her first adviser for the guidance, assistant, encouragement and valuable suggestions and critics from these great heroes in education, in the process of writing this thesis.

Secondly, the writer would like to express her gratitude to Dr. Rahmad Husein, M.Ed., her second adviser for his available time spent for consultation, great supervision and full support in shaping this thesis.

assisted her in the process of administration requirement during the process of her study in the postgraduate program.

She would like to take special occasion to express her gratitude to Prof. Amrin Saragih, M.A., Ph.D., Prof. Dr. Sumarsih, M. Pd., and Dr. Anni Holila Pulungan, M. Hum., being her reviewers and examiners for the valuable inputs to be include in this thesis. Furthermore, she would like to express her high appreciation to all lectures of English Applied study program UNIMED Medan, who have shared their knowledge and experience her during study. And thank you note addressed to her colleagues in class A of English Applied Linguistics in take XXIII for the cooperation and friendly being in the “same boat”.

Last but not least, on a personal level, the writer would like to dedicate her love and sincerest gratitude to her beloved parents Tenang Ginting and Rosmalinda Tarigan, her beloved sister Sagitha Devy Ginting for her sincere and most reliable comfort and above all, their love and support. May God consecrate to them. Amin.

Medan, August 2015

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER II. RELATED LITERATURE REVIEW ... 11

2.1Language Change ... 11

2.2.1 The Occurrence of Lexical Change ... 20

2.3 Karonese and Karo Language ... 44

2.3.1 Agricultural Lexis in Cakap Karo ... 46

2.4 Relevant Studies... 48

2.5 Conceptual Framework ... 52

CHAPTER III. RESEARCH METHOD ... 54

3.1Research Design... 54

3.2 Data and Source of Data ... 54

3.3 The Instruments of Data Collection ... 55

3.4 The Procedures of Data Collection ... 56

3.5 The Technique of Data Analysis ... 57

3.6 Trustworthiness of the Study ... 58

CHAPTER IV. DATA ANALYSIS, FINDINGS AND

DISCUSSION ... 60

4.1 Data Analysis ... 60

4.1.1 The Levels of Agricultural Lexical Loss in Cakap Karo ... 61

4.1.2 Patterns of Loss of Agricultural Lexis in Cakap Karo ... 65

4.1.2.1 Loss of Agricultural Lexis in Cakap Karo ... 65

4.1.2.1.1 Potential Agricultural Lexical Loss of Cakap Karo ... 66

4.1.2.1.2 Total Agricultural Lexical Loss of Cakap Karo ... 69

4.1.3 The Reasons of Agricultural Lexical Loss of Cakap Karo ... 70

4.2 Research Findings ... 72

4.3 Discussion ... 72

4.3.1 The Level of Agricultural Lexical Loss of Cakap Karo ... 73

4.3.2 The Pattern of Agricultural Lexical Loss of Cakap Karo ... 74

4.3.3 The Reasons of Agricultural Lexical Loss of Cakap Karo ... 75

CHAPTER V. CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS ... 76

5.1 Conclusion ... 76

5.2 Implications... 77

5.2 Suggestions ... 78

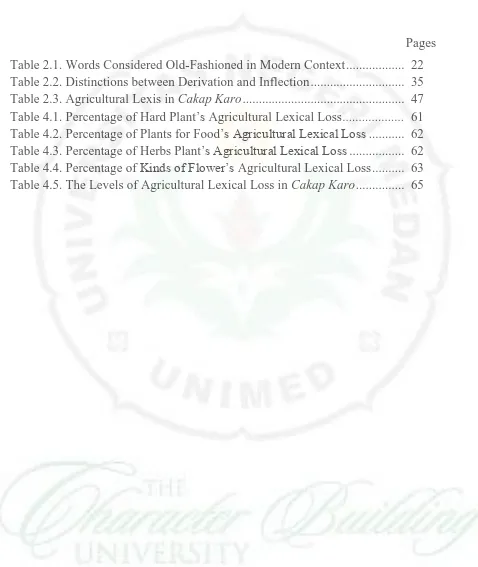

LIST OF TABLES

Pages

Table 2.1. Words Considered Old-Fashioned in Modern Context ... 22

Table 2.2. Distinctions between Derivation and Inflection ... 35

Table 2.3. Agricultural Lexis in Cakap Karo ... 47

Table 4.1. Percentage of Hard Plant’s Agricultural Lexical Loss ... 61

Table 4.2. Percentage of Plants for Food’s Agricultural Lexical Loss ... 62

Table 4.3. Percentage of Herbs Plant’s Agricultural Lexical Loss ... 62

Table 4.4. Percentage of Kinds of Flower’s Agricultural Lexical Loss ... 63

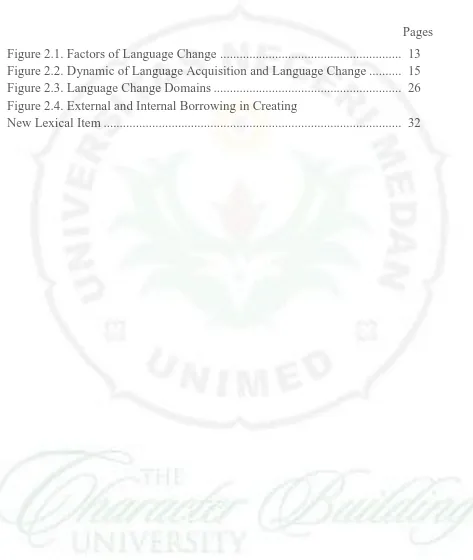

LIST OF FIGURES

Pages

Figure 2.1. Factors of Language Change ... 13 Figure 2.2. Dynamic of Language Acquisition and Language Change ... 15 Figure 2.3. Language Change Domains ... 26 Figure 2.4. External and Internal Borrowing in Creating

LIST OF APPENDICES

Pages

Appendix 1. List of Agricultural Lexical Loss In Cakap Karo ... 84

Appendix 2. The Format of Questionnaire ... 92

Appendix 3. Agricultural’s Hard Plants Lexical Loss In Cakap Karo ... 98

Appendix 4. Agricultural’s Plants for Food Lexical Loss In Cakap Karo... 102

Appendix 5. Agricultural’s Herbs Plant Lexical Loss In Cakap Karo ... 104

Appendix 6. Agricultural’s Flower Lexical Loss In Cakap Karo ... 105

Appendix 7. Percentage of Agricultural’s Hard Plants In Cakap Karo ... 106

Appendix 8. Percentage of Agricultural’s Plants For Food In Cakap Karo ... 110

Appendix 9. Potential Loss of Agricultural Lexicons of Cakap Karo ... 112

Appendix 10. Total Loss of Agricultural Lexicons of Cakap Karo ... 116

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

A. The Background of the Study

Language change may happen to any language where the influencing

language is considered more prestigious and valuable. This study looks at the

phenomena of ethnic language change among Karonese people in linguistic area

of phonology, lexicon and semantic. The culture of Karonese people in the

highlands of Karo, North Sumatera, which is located approximately 78 km from

Medan, the capital of North Sumatera province, cannot separated from the

language that is used every day in daily life called Cakap Karo or Karo language,

because basically language is part of culture. With a number of speakers are above

five hundred thousand people in 1991 and domiciled in the adjacent area around

the 4 largest area of Tanah Karo in city districts – Kabanjahe, Simpang Empat

sub-district, city tourism of Berastagi dan Tigapanah sub-district and 10 other

districts make Cakap Karo as ethnic languages are still quite often used.

Indonesia has a language which is known as Bahasa Indonesia. Besides,

Indonesia has many local languages such as Javanese, Sundanese, Bataknese,

Karonese, etc. The Karonese is local language which is used by the Karo people

to communicate among them. It hassome varieties, one of them is dialect. Jufrizal

(1999:101) defines dialect as regional variety of language that may different from

other varieties of the language in features of it is vocabulary, grammar and

only if there isa strong tradition of writing in local variety. It means that dialect is

the language that is used by people who still have strict tradition strictly in a

regional.

Karo language as one of hundreds of Indonesian vernacular is an

Austronesia language spoken on Karo Land which is related to Simalungun

language, Alas language and Gayo language. Karonese people speak Karo

language, which is also known as Cakap Karo. Karo language is spoken in five

different dialects, namely dialects of Julu, Teruh Deleng, Singalur Lau, Jahe and

Liang Melas. Julu dialect is used in Kabanjahe sub-district, Simpang Empat, Tiga

Panah, Berastagi, and surrounding. Teruh Delung Dialect used in Kuta Buluh

sub-district and partially in Payung sub-sub-district (Prinst, 2002). In his book, he added

that Singalur Lau dialect is used in Juhar, Tiga Binanga, Singgamanik and

Perbesi. Jahe dialect (Hilir) is used in Karo Jahe (Deliserdang-Medan) and

partially in Langkat (Hulu). Liang Melas dialect used in Lau Melas sub-district.

Those differences can be seen from the sound of word or from the intonation of

words. But most of Karonese people in North Sumatera use their own dialect

when they communicate with people from different dialect and they still

understand each other. Chaer (1995:81) says that variation is variation of language

occur because of social variation and regional variation. Variation of language

also occurs because of differences social status.

The Karo Language is used by Karonese people. But there are variations

of the language that are caused by regional and social variation. Differences of

of those variations the result it makes language change. In changing of one

language, there are semantic changing, phonology, morphological, lexical, and

syntax changing. Language change can because of many factors like time, age,

regional, and social status. Thus, the dialect that is used by people in regional can

change, because of some factors like time, age, change of regional, social status

and the lost of native speakers.

Any language in the world tends to change which might be in the forms of

lexical, morphological, syntactical, semantic and pragmatic changes (Dhaki, 2011:

1). Specifically, lexical change is manifested in every single of lexical classes of a

language, such as noun, verb, adjective, adverb, pronoun, preposition, conjunction

and interjection. A case of lexical change in Karo language is the word abal-abal,

a tubes of bamboo used as a place to store salt for durability. It is regarded one of

lexical loss of Karo language because it is not practiced anymore. Another

empirical example is aron (clearing forests for agriculture and farms manually

using human hands, performed together as a wholesale activities of fellow

members of the community where everyone involved working as a form of mutual

aid) which is categorized as a verb becomes a noun which means “laborers who

do the grunt work for someone else”. This phenomenon, which is caused by the

metaphorical application, is called as semantic change due to its lexical class

movement from verb to noun. Empirically, the older speakers of Karo language

experience that the youngsters are reluctant to use their mother tongue so that they

sometimes mix between Karo Language and Indonesian Language. These

examples, it is feasible to assert that the lexical change contains types, patterns,

and reasons. Lexical change type is defined as the sort of change realized in the

lexicons, which might be loss of lexicon or change of meaning like the example

above.

The influence of modern things nowadays is regarded as factor for Karo

language existence and maintenance. The fashionable and innovative devices and

needs bridge the Karo language users’ attention to lexical modernization; a

process by which a language standardizing, enhancing, and expanding its domains

of activity (Kaplan and Baldauf, 1997: 69). On the other hand, the popularity of

Karo Land as one of the most beautiful tourism areas governs the existence and

maintenance of Karo language. This is because the great possibility of

code-switching between Karo language and tourist’s language, which serve as a major

factor of a language change (Lindstrom, 2007: 232), take place.

There will be also a tendency to the change of Karo language when its

speakers are more educated. This has been proved by the fact the role of Karo

language use in educational setting is not the same at home. This is definitely

rooted from the empirical evidence that the medium of teaching and learning in

Karonese schools is Indonesian. Consequently, the students’ attitudes towards

Karo language eventually decreases which automatically makes Indonesian

dominantly used in their day life. This condition, which serves as determining

factor of lexical loss, makes the Karo lexical replaceable by Indonesian lexical

Religion is a particular system of faith and worship based on the belief of

language speakers serves as another influence of Karo Language existence and

maintenance (Dhaki, 2011: 4). This condition can be seen in the words rumah

begu (house of ghost), naleng tendi (summon spirits), ercibal (presenting

something as an offering), erpangir (washing hair with lemon juice, coconut oil,

ash kitchen, etc which is used to counteract the impending doom or as treatment)

which has been loss because there is nobody of young people thinks of those

words. It can be said fades away. The terms above loss with the arrival of religion

that has been legalized by country, which are Christian and Islamic to Karo Land

(Tanah Karo).

A language is fundamentally viewed as much more than a system of

communication. It is symbolic marker that distinguishes who belongs to a group

and who is outside (Dhaki, 2011: 4). In this case language in general and Karo

Language in particular is considered as a central feature of Karonese ethnics the

reflection of Karonese people identity. Theoretically, according Moyna (2009:

131-132) language changes resulted from the social and individual factors. Social

factors are the contact between speakers of different varieties due to conquest,

migration, culture, education, economic and religion. The social or external

factors of language change are not only including the type of input in the

environment but also the mechanisms and rates of input processing. The

mechanisms are concerned with the techniques and methods of input provided to

the language speakers, whereas rates deal with the amount of input itself. On the

resulted from an entire generation of child acquisition. This theory has been

proved on the changes of Karo Language lexicons above.

Many young people tend to use different words than the old generation

(Lishandi, 2013: 134). There are many forms of lexical loss in this language that

can threat the maintenance of this language. When young people see their words

and then use them in their daily communication, they will consider the word as

their native language. So, as a result it can make the native words lost. That’s why

the writer is interesting in observing the lexical change particularly lexical loss of

Karo Language in agriculture. The writer just focus on agriculture sector because

the lexical loss in general is too wide to observed and the research about lexical

loss of Karo Language in agriculture has not observed yet before. Moreover, the

influence of technology and modernization is more noticeably in agriculture

because almost of all people in Karo Land working in the field as a farmer. The

writer would like to know the processes of lexical loss and the reasons of lexical

loss occur in Karo Language.

Looking from Kamus Karo Indonesia (2002) point of view, so many

names of plants in Karo Language are not recognized anymore by Karo people

nowadays. For examples:

Katola (the clamber plant with long fruit and the seed looks like cucumber, the

outside of the skin is smooth but the inside is fibred).

Katemba (a kind of plant with red flower),

Kasemba (a kind of plant like shrubs, wide leave looks like fingers and the

Kempidi (a kind of wild areca-palm/pinang and the fruit smaller than

areca-palm/pinang),

Kempawa (a kind of palm usually live in the forest), etc.

It is one of the reasons why the writer interested in observing lexical loss of Karo

Language in agriculture sector. There are so many plants that has not been planted

anymore by the Karo people and made in the names loss in the course of the

world. It automatically influenced the lexicon in Karo Language and resulted in

lexical loss in Karo language in agriculture. For that reasons, the writer interested

in observing in agriculture especially on agricutural’s plants, because so much

plants loss in the world and made those lexicons are lost automatically and not

recognized anymore by Karo people.

The phenomenon of lexical loss happens in Karo Language. One of the

cases of lexical loss in Karo Language happened in agriculture sector. For

example:

Cuan (similar to hoe used for tossing and turning the soil)

Ambung (a basket used as place of gambir)

Mesie (the first rice after harvest)

Permakan (shepherd of buffalo/cow)

Barajenggi (celery)

Lexical loss is due to internal and external factors (Varshney, 1995: 283).

He added that homonymic clash, phonetic attrition and the need to shorten

common words are common internal causes. Homonyms are words which have

is abang. The first meaning is kapok tree that the flowers bloom simultaneously

and when the wind floating, the flower flying to everywhere. The second meaning

is brother. The existences of homonyms need to lead the word loss. It only does so

if the homonyms crop up in the same context and cause confusion. As there were

numerous contexts when the two could become confused, the first meaning of

abang dropped out of existence. That is one of the reasons why lexical loss occurs

in Karo language.

External causes of lexical loss are, broadly speaking, historical or social

(Varshney, 1995: 283). Words such as biwa, bedi-bedi, beras-beras, are not more

current, because these objects are no longer part of everyday life. They have thus

dropped out for historical reasons. Social reasons are more diverse. Sometimes

alternative lexical items are in use depending on religion or social class, as with

pairs such as table, napkin, and serviette, radio and wireless. If one of the pairs

becomes more socially acceptable, the other is likely to drop out of use. In Karo

Language, for example, the word tongat is more in use than pongat (common

designation for boys). An interesting type of social cause is lexical loss through

taboo. For example, palu is favored more than entek (beat). Karonese people

attempts to avoid the word entek because of taboo to spoken by people in there.

That word sometimes substituted by word palu, tukul or pekpek. From the

phenomenon arise some problems that make this research is interest to be

observed.

From the data above, the common lexical loss problems occurring in Karo

analyze the lexical loss in Karo language especially in agriculture sector. Finally,

this study is entitled “Loss of Agricultural Lexis in Cakap Karo”. This study is

to find out the lexical loss which has occurred in Karo Language followed by how

and why the lexicons have been lost.

1.1 The Problems of the Study

The problems of the study is presented in the question of “How is the

agricultural lexicon loss of Cakap Karo?” this question then is elaborated into

more particular questions, such as the following.

1) What are the levels of agricultural lexical loss in Cakap Karo?

2) How do the patterns of agricultural lexicons of Cakap Karo?

3) Why do the agricultural lexicons of Cakap Karo lose the way they do?

1.2 The Objectives of the Study

The research is aiming at studying the new phenomenon on lexical loss of

Cakap Karo. It specifically attempted to objectively describe the lexical loss as

well as the ways and reasons of lexical loss of Cakap Karo. Thus, the objectives

of this study were elaborated as following:

1) To investigate the level of agricultural lexical loss in Cakap Karo

2) To describe the patterns of agricultural lexical loss of Cakap Karo

3) To explain the reasons of agricultural lexical loss of Cakap Karo

1.3 The Scope of the Study

The various language change domains and the numerous lexical loss of

change, particularly to lexical loss of Cakap Karo of agriculture’s plants. More

specific it is in an attempt to provide an objective and explanative description of

the loss of agricultural lexis in Cakap Karo.

1.4 The Significance of the Study

Findings of the research are expected to be useful for the readers both

theoretically and practically in some respects:

1) Theoretically, the findings can be useful for enriching the theories on

lexical loss particularly for understanding the patterns and the reasons of

lexical loss in Cakap Karo.

2) Practically, the findings can be useful for those who have focus on

linguistic study especially the lexical loss in Cakap Karo. Moreover, the

ideas and the point of views of the findings can significantly be useful to

be used as:

a. Review of literature for the coming researchers.

b. Material reference for language learning particularly related to lexical

loss.

c. Material for helping people particularly Karo people in comprehending

CHAPTER V

CONCLUSION, IMPLICATIONS AND SUGGESTIONS

5.1 Conclusion

Based on the description, explanation and discussion about the level,

patterns and reasons of agricultural lexical loss in Cakap Karo in previous

chapters, conclusion is drawn as follows:

1) In Cakap Karo there are 249 (two hundreds and fourty nine) lexicons

regarded as agricultural lexical loss that distributed to some

respondents might be classified into four levels of agricultural lexical

loss. The level of agricultural lexical loss of Cakap Karo of hard

plant category is fourth level (not know and use), which is 91.77%.

The level of agricultural lexical loss of Cakap Karo of plants for

food category is fourth level (not know and use), which is 85.19%.

The level of agricultural lexical loss of Cakap Karo of herbs plant

category is fourth level (not know and use), which 91.67%. And the

level of agricultural lexical loss of Cakap Karo of kinds of flower

category is fourth level (not know and use), which is 92.31%. From

this data obtained, it is obvious that the highest level of agricultural

lexical loss in Cakap Karo occurred in kinds of flower category and

the lowest level of agricultural lexical loss in Cakap Karo occurred

in plants for food category.

2) The agricultural lexical loss is proportionally patterned into potential

potential agricultural lexical loss have found among 249

agriculture’s plant lexical losses. On the other hand, there are 146

(one hundred forty six) total agricultural lexical loss have found

among 249 agriculture’s plant lexical losses.

3. The division of lexical loss reasons in Cakap Karo varies and is

considerably linkable with every sort single of lexical loss pattern.

Linguistic, prestige, culture and technology play the important role

as the influential causes of lexical loss.

5.2Implications

The conclusion drawn above convincingly yields a couple of

implication:

1. The levels of agricultural lexical loss in Cakap Karo occur on four

categories: hard plants, plants for food, herbs plant, kinds of flower.

The highest level of agricultural lexical loss in Cakap Karo occured

in kinds of flower category which highly due to the influence of

Bahasa Indonesia as the national and official language. The lowest

level of agricultural lexical loss in Cakap Karo occured in plants for

food category which highly due to their attention to their culture and

they need to maintain their food supply, and also they have still

doing plantation to this plants to support their life..

2. Eventhough the number of hard plants is much bigger but their

existence in Karo region has been loss because of the natural disaster

made the plants are much loss and made the farmers experienced

nightmare to their field.

3. The deviation of number of every single sort of lexical loss is

definitely implicated by the influence and status of Karo people’s

characteristics of life, culture, and technological development.

4. In educational setting, the various loss of agricultural lexis in Cakap

Karo implicitly implicate that language standardization, i.e.

selection, codification, elaboration and acceptance, is not totally

employed, consequently it bears an enormously complicated

problem impeding the success of teaching and learning Cakap Karo

to the next generation.

5.3Suggestions

Dealing with the findings of this research which are problematic,

some worth considering pieces of suggestion are provided below.

1. It is advisable to the language users of Cakap Karo to use Cakap

Karo in their daily life at home, office and school. By doing so, their

language attitude towards Cakap Karo itself will eventually increase.

2. It is strongly suggested to the local Government of Karo regency to

take into account about the maintenance and standardization Cakap

Karo through the establishment of standardized Cakap Karo

dictionary, formulized Cakap Karo grammar, and specified spelling

system. Through this recorded material, the existence of Cakap Karo

3. It is also expected to the teachers, students and other practitioners to

make writing in Cakap Karo. This technique is indispensably useful

to gain the access of another expert’s interest and attention about the

entity of Cakap Karo.

4. To the linguists, researchers and those who are extremely interested

to conduct a scientific study on Cakap Karo, it is suggested to

investigate the practical techniques in decreasing the number of

lexical loss. Through this step, the development Cakap Karo will

REFERENCES

Adisutrisno, D. W. 2008. Semantics: An Introduction to the Basic Concepts. Yogyakarta: C.V. Andi Offset.

Ali, M., and Mohideen, S. 2010. Awareness of Contemporary of Lexical Change for Professional Competence in English Language Education. European Journal of Social Sciences. 13(1), 101-107.

Bangun, T. (1986b). Manusia Batak Karo. Jakarta: Inti Idayah Press.

Bloomfield, L. 1933. Language. London: George Allen & Unwind.

Bogdan, R. C., and Biklen, S. K. 1992. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. The United States of America: Allyn and Bacon.

Brinton, L. J and Traugott, E. C. 2005. Lexicalization and Language Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chaer, Abdul. 1995. Sosiologistik Perkenalan Awal. Jakarta: Rineka Cipta

Christiansen, M. H. and Dale, R. 1992. Language Evolution and Change. New York: Cornell University Press.

Clark, R and Roberts. 1993. A Computational Model of Language Learn Ability and Language Change. In Niyogy, P and Berwick, R. C. 1995. The Logical Problem of Language Change. Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Cohen, L. et al. 2007. Research Methods in Education. Milton Park: Routledge.

Denham, K. and Lobeck, A. 2005. Teaching Kids about Language Change, Language Endangerment, and Language Death. Mahwan, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. 1994. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

Dhaki, Saniago. 2011. Lexical Change of Southern Dialect of Li Niha. Medan: Postgraduate School of State University of Medan

American Hungarian. SKY Journal of Linguistics. Vol 19, 131-146.

Gao, L. 2008. Language Change in Progress: Evidence from Computer-Mediated Communication. Proceedings of the 20th North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics (NACCL-20). Vol. 1, pg. 361-377. Ohio: The Ohio State University.

Gleason, H. A. 1961. An Introduction to Descriptive Linguistics.New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Gonzales and Cruz. 2014. Approaching Lexical Loss in Canarian Spanish Undergraduates: A Preliminary Assessment. Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Revista de Linguistica y Lenguas Aplicadas 9 (2014), 33-34.

Gumperz, J. 1982. Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hana, J. 2006. Language Change. Retrived on December, 15th 2014 from http://www.pdfound.com

Hickey, R. 1987. Language Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Holmes, J. 2008. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. ThirdEdition. Harlow: Person.

Hudson, R. A. 1985. Sociolinguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hurford, J.M., and Heasley, B. 1995. Semantic: A Coursebook. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, E. 1994. The Relationship between Lexical Variation and Lexical Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jones, M. C. And Singh. I. 2005. Exploring Language Change. London and New York: Routledge.

Jufrizal. 1999. Introduction to General Linguistics. Padang: DIP Universitas Negeri Padang.

Kaplan, R. B., and Baldauf Jr. R. B. 1997. Language Planning: From Practice to Theory. Clevedon, Philadelphia, Toronto, Sydney and Johannesburg: Multilingual Matters.

Lass, R. 1987 English Phonology and Phonological Theory: Synchronic and

Lindstrom, L. 2007. Bismala into Kwamera: Code-Mixing and Language Change on Tanna (Vanuata). University of Tulsa Press, E-ISSN 1934-5275.

Lishandi, Bovi. 2013. Lexical Shift and Lexical Change in Minangkabaunese Used in Batusangkar. Padang: Universitas Negeri Padang.

Meyer, C. 2006. Multiple Penelitian. Jakarta: Ghalia Indonesia.

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. 1984. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. California: Sage Publication.

Moyna, M. I. 2009. Child Acquisition and Language Change: Voseo Evolution in Rio de la Plata Spanish in Elected Proceedings of the First Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Cascadilia Proceedings Project. (p. 131-142)

Niyogi, P. and Berwick, R. C. 1995. The Logical Problem of Language Change New York: Cambridge University Press.

Prinst, Darwin. 2002. Kamus Karo-Indonesia. Medan: Bina Media.

Purba, Elkana A. 2014. Perkembangan Aron Pada Masyarakat Karo di Desa Rumah Kabanjahe Kecamatan Kabanjahe Kabupaten Karo. http//: www. digilib. UNIMED.ac.id/UNIMED-undergraduate-sk142423/34596/Aron.

Sembiring, S. 2004. Ahli Kode Penutur Bahasa Karo Kelurahan Sempakata Kecamatan Medan Selayang. Pascasarjana Universitas Sumatera Utara: Thesis.

Varshney, R. L. 1995. An Introductory Textbook of Linguistics and Phonetics. Rampur Bagh: Student Store.

Wardaugh, Ronald. 2007. An Introduction to Sociolinguistic. New York: Blackwell.

Wagino. 2015. Kabupaten Karo. http//: www.

wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabupaten_Karo. Accessed on 20 February 2015.

Yang, C. D. 2001. Internal and External Forces in Language Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.