Safety Audits

Lawrence B. Cahill et al.

Environmental

Health and

Safety Audits

8th Edition

Government Institutes Rockville, Maryland

Lawrence B. Cahill

Raymond W. Kane

Thomas R. Vetrano

James C. Mauch

Marc E. Gold

Michael M. Meloy

Phone: (301) 921-2300 Fax: (301) 921-0373 Email: giinfo@govinst.com Internet: http://www.govinst.com

Copyright © 2001 by Government Institutes. All rights reserved.

03 02 01 00 5 4 3 2 1

No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or the use of any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. All requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be directed to Government Institutes, 4 Research Place, Suite 200, Rockville, Maryland 20850, USA.

The reader should not rely on this publication to address specific questions that apply to a par-ticular set of facts. The author and publisher make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the completeness, correctness, or utility of the information in this publication. In addition, the author and publisher assume no liability of any kind whatsoever resulting from the use of or reliance upon the contents of this book. Government Institutes, a Division of ABS Group Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Environmental, health and safety audits / Lawrence B. Cahill ... [et al.] p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-86587-825-0

1. Environmental auditing--United States. I. Cahill, Lawrence B. II. Environmental audits.

TD194.7.E597 2001 658.4’08--dc21

Preface . . . xxiii

About the Editor and Principal Author . . . xxv

Contributing Authors . . . xxvii

Acknowledgments . . . xxxi

PART I. MANAGING A PROGRAM Chapter 1: Perspectives in EH&S Auditing . . . 3

Chapter 2: Government Perspective . . . 25

Chapter 3: Legal Considerations . . . 47

Chapter 4: Elements of a Successful Program . . . 65

Chapter 5: Impact of International Standards on EH&S Audit Programs . . . 89

Chapter 6: The Challenges of Meeting ISO 14000 Auditing Guidelines: Audit Program Gaps . . . 109

Chapter 7: A Review of Some Typical Programs . . . 119

Chapter 8: Benchmarking EH&S Audit Programs: Best Practices and Biggest Challenges . . . 129

Chapter 9: Environmental Auditor Qualifications: Great Expectations . . . 143

Chapter 10: Training EH&S Auditors . . . 149

Chapter 11: EH&S Audit Training in the Asia Pacific . . . 155

Chapter 12: Information Management . . . 163

Chapter 13: Using Groupware to Manage the EH&S Audit Program Documentation Process . . . 171

Chapter 14: Managing and Critiquing an Audit Program . . . 179

PART II: CONDUCTING THE AUDIT Chapter 15: Conducting the EH&S Audit . . . 193

Chapter 16: Typical Compliance Problems Found During Audits . . . 223

Chapter 17: Conducting Effective Opening and Closing Conferences . . . 267

Chapter 18: Auditing Dilemmas . . . 279

Chapter 19: Preparing Quality EH&S Audit Reports . . . 287

Chapter 20: Environmental Auditing: A Modern Fable . . . 307

Chapter 21: Achieving Quality Environmental Audits: Twenty Tips For Success . . . . 321

PART III: SPECIAL AUDITING TOPICS Chapter 22: Property Transfer Assessments . . . 331

Chapter 23: Top Ten Reasons Why Phase I Environmental Assessment Reports Miss the Mark . . . 355

Chapter 24: Waste Contractor Audits . . . 367

Chapter 25: Waste Minimization or Pollution Prevention Audits . . . 387

Chapter 26: Evaluating Management Systems on EH&SAudits . . . 395

Chapter 27: International EH&S Audits . . . 403

APPENDICES Appendix A: References . . . 419

Appendix B: Federal Register Notes . . . 423

Appendix C: Sample EPCRA Audit Protocol . . . 455

Appendix D: Problem Solving Exercises . . . 485

Appendix E: Summary of Audit Programs . . . 507

Appendix F: Model EH&S Audit Program Manual . . . 533

Appendix G: Model Pre-Audit Questionnaires for EH&S Audits . . . 567

Appendix H: Model EH&S Audit Opening Conference Presentation . . . 597

Appendix I: Model Environmental Audit Report . . . 605

Appendix J: Model Environmental Audit Appraisal Questionnaire . . . 623

Appendix K: Model Management Presentation . . . 627

List of Figures and Exhibits . . . xx

Preface . . . xxiii

About the Editor and Principal Author . . . xxv

Contributing Authors . . . xxvii

Acknowledgments . . . xxxi

PART I: MANAGING A PROGRAM Chapter 1: Perspectives in EH&S Auditing . . . 3

Why Audit? . . . 3

Growth of Regulations . . . 4

Growth in Visibility . . . 8

Growth in Enforcement . . . 9

Impact on the Regulated Community . . . 11

Evolution of Environmental Auditing . . . 16

EH&S Auditing Organizations . . . 17

EH&S Auditing Roundtable . . . 17

The Board of EH&S Auditor Certifications . . . 18

Defining Environmental Audits . . . 18

Advantages and Disadvantages . . . 20

Trends in EH&S Auditing . . . 21

Chapter 2: Government Perspective . . . 25

Introduction . . . 25

U.S. EPA Policy Encourages Use of Environmental Auditing . . . 27

U.S. EPA’s 1986 Auditing Policy and Elements of Effective Audit Programs . . . 28

U.S. EPA’s Audit Policy . . . 30

Audit Policy Incentives . . . 30

Safeguards . . . 31

Additional Incentives and Behavior . . . 31

Open and Inclusive Process Utilized to Develop the Audit Policy . . . 32

Widespread Use of the Audit Policy to Date with High Satisfaction Rate . . . 33

Audit Policy Conditions . . . 33

Relationship to State Laws, Regulations, and Policies . . . 38

Applicability and Effective Date . . . 38

Policy Redresses Industry Concerns . . . 40

Use of Audit Policy in Corporate-Wide Audit Agreements and Compliance

Incentive Programs . . . 42

Corporate-Wide Audit Agreements . . . 42

Compliance Incentive Programs . . . 43

Audit Policy Information Resources . . . 43

Conclusions . . . 44

OSHA’s 2000 Self-Audit Policy . . . 44

Chapter 3: Legal Considerations . . . 47

Introduction . . . 47

Function of Environmental Assessments . . . 48

Role of Environmental Assessments . . . 49

Federal Policies Encouraging Environmental Assessments . . . 50

Overview and Evolution of U.S. EPA Policies . . . 50

U.S. DOJ Policy . . . 55

Protection Of The Confidentiality Of Environmental Assessments Under Existing Law . . . 55

Attorney-Client Privilege . . . 56

Work-Product Doctrine . . . 57

Self-Evaluative Privilege . . . 58

State Environmental Audit Legislation and Policy . . . 60

Practical Considerations and Recommendations For Performing Self-assessments . . . 61

Chapter 4: Elements of a Successful Program . . . 65

Principles of an Audit Program . . . 65

Planning the Program . . . 66

Program Objectives . . . 68

Roles and Responsibilities . . . 70

Legal Protections . . . 72

Scope and Coverage . . . 72

Facility Audit Schedules . . . 74

Auditor Selection and Training . . . 78

Audit Procedures . . . 79

Audit Reports and Documentation . . . 79

Audit Program Management & Evaluation . . . 81

Audit Program Support Tools . . . 81

A Key Program Issue: Corporate Standards and Guidelines . . . 84

Development of Waste Discharge Inventories . . . 85

Internal Reporting of Environmentally Related Incidents . . . 86

Environmental Recordkeeping/Records Retention Procedures . . . 86

External Regulatory Inspection Procedures . . . 87

Additional Sampling . . . 87

Continuous Review . . . 87

Evaluating the Results and Implementing the Solutions . . . 88

Chapter 5: Impact of International Standards on EH&S Audit Programs . . . 89

The Key Initiatives . . . 91

The CERES Principles . . . 91

International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Environmental Standards . . 93

The European Community Eco-Management and Audit Scheme . . . 95

The Chemical Industry’s Responsible Care Program . . . 96

U.S. EPA and OSHA Audit Policies and Performance Programs . . . 97

The U.S. Sentencing Commission’s (USSC) Guidelines for Mitigating Factors . . 98

Environmental, Health, and Safety Auditing Roundtable (EAR) Auditing Standards . . . 99

Standards for Performance of EH&S Audits (February 1993) . . . 99

Standard for the Design and Implementation of an EH&S Audit Program (January 1997) . . . 100

The Board of EH&S Auditor Certifications (BEAC) Auditing Standards . . . 101

Corporate Responses . . . 102

Appointment of Environmental Experts to Corporate Boards . . . 102

Voluntary Public Reporting . . . 102

Third-Party Program Evaluations and Certifications . . . 105

Benchmarking Studies . . . 105

Conclusion . . . 108

Chapter 6: The Challenges of Meeting ISO 14000 Auditing Guidelines: Audit Program Gaps . . . 109

A Process to Evaluate the Adequacy of Resources . . . 110

A Process to Evaluate Auditee Cooperation . . . 111

A List of Auditees in the Audit Report . . . 112

Identification of “Obstacles Encountered” in the Audit Report . . . 113

Documentation of “Findings of Conformity” . . . 115

An Appropriate Code of Ethics . . . 115

A Non-Disclosure or Records Retention Policy . . . 116

A Formal Audit Plan . . . 117

Auditor Independence . . . 118

Chapter 7: A Review of Some Typical Programs . . . 119

Program Overview and Scope . . . 120

Program Name . . . 120

Start Date . . . 122

Purpose . . . 122

Program Organization . . . 122

Program Scope . . . 123

Program Methodology . . . 123

Audit Methodology . . . 123

Reporting Findings . . . 125

Follow-Up Mechanisms . . . 125

Program Operations . . . 126

Audit Staffing . . . 126

Audit Duration . . . 126

Number of Plants Per Year Audited . . . 126

Frequency of Audits . . . 126

Conclusion . . . 127

Chapter 8: Benchmarking EH&S Audit Programs: Best Practices and Biggest Challenges . . . 129

Overview of Benchmarking . . . 130

Precisely Define the Scope . . . 131

Select Target Companies Using a Variety of Techniques . . . 131

Create Participation Incentives . . . 132

Develop Measurable Criteria . . . 132

Utilize Focus-Group Sessions . . . 132

Best Practices . . . 133

Reports to Management . . . 133

Relationship to Compensation . . . 133

Use of Spill Drills . . . 134

Red Tag Shutdowns . . . 135

Community Participation . . . 135

Next Site Participation . . . 135

Use of Portable Computers, Intranets, and the Internet . . . 135

Assessment of Ancillary Operations . . . 136

Use of Verification Audits . . . 137

Site-Satisfaction Questionnaire . . . 138

Periodic Third-Party Evaluations . . . 138

Biggest Challenges . . . 139

The Program Manual . . . 139

Protocol Updating . . . 140

State Regulatory Review . . . 140

Unclear or Unknown Corporate Standards . . . 141

Misleading Closing Conferences . . . 141

Timeliness and Quality of the Report . . . 141

Insufficient Follow-Up . . . 142

Lack of Program Metrics . . . 142

Chapter 9: Environmental Auditor Qualifications: Great Expectations . . . 143

Core Skills . . . 144

Learned Skills . . . 144

Inherent Skills . . . 145

Observations in the Field . . . 146

The Worst Attributes . . . 146

The Best Attributes . . . 147

Making Good Things Happen . . . 148

Conclusion . . . 148

Chapter 10: Training EH&S Auditors . . . 149

The Need . . . 149

Selecting the Trainers . . . 150

Selecting the Trainees . . . 151

Selecting the Setting . . . 151

Selecting the Techniques . . . 152

Lecture . . . 152

Problem Solving . . . 152

Role-Playing . . . 153

Keys to Making It Work . . . 153

Chapter 11: EH&S Audit Training in the Asia Pacific . . . 155

First Stop: Singapore . . . 156

The Transition: Singapore to Japan . . . 159

Chapter 12: Information Management . . . 163

Regulatory Databases . . . 164

Automated Checklists . . . 165

Advantages . . . 166

Disadvantages . . . 167

Evaluating Auditing Software Systems . . . 168

Chapter 13: Using Groupware to Manage the EH&S Audit Program Documentation Process . . . 171

Importance of Sound Information Management . . . 171

Traditional Responses to Audit Document Management . . . 172

The Groupware Solution . . . 174

Conclusion . . . 177

Chapter 14: Managing and Critiquing an Audit Program . . . 179

Beginning a Program . . . 179

Develop an EH&S Audit Policy and Procedure . . . 180

Set Up the Organization . . . 181

Develop Tools . . . 182

Train Staff . . . 182

Test the Program . . . 183

Set Review Schedule . . . 183

Conduct Audits . . . 183

Implement Full Program . . . 184

Managing a Program . . . 184

Assessment Tools . . . 184

Management Reports . . . 185

Staff Management . . . 187

Quality Assurance . . . 187

Maintaining Awareness . . . 188

Conclusion . . . 189

PART II: CONDUCTING THE AUDIT Chapter 15: Conducting the EH&S Audit . . . 193

Introduction . . . 193

Team Selection and Formation . . . 197

Completion and Review of the Pre-Audit Questionnaire . . . 198

Review of Relevant Regulations . . . 199

Definition of Audit Scope and Establishment of Team Responsibilities . . . 199

Development of a Detailed Audit Agenda or Plan . . . 201

Review of Audit Protocols . . . 204

Arrange Logistics . . . 204

On-Site Activities . . . 205

Opening Conference . . . 205

Orientation Tour . . . 205

Records/Documentation Review . . . 207

Interviews with Facility Staff . . . 209

Schedule Interviews Ahead of Time . . . 209

Conduct Interviews in the Workspaces . . . 210

Be Sensitive to the Interviewee’s Nervousness and Defensiveness . . . 210

Avoid Yes/No Responses to Questions . . . 211

Physical Inspection of Facilities . . . 212

Inspect Remote Areas . . . 213

Observations Must Be Timed to Verify Compliance . . . 214

Observe the Facility from the Outside . . . 216

Observe Emergency Response Plans in Action . . . 216

Observe Sampling/Monitoring Procedures . . . 217

Daily Reviews and Pre-Closing Conference . . . 220

The Closing Conference . . . 221

Preparing for the Closing Conference . . . 221

Conducting the Closing Conference . . . 222

The Audit Report . . . 222

Chapter 16: Typical Compliance Problems Found During Audits . . . 223

EH&S Audits: What Can Go Wrong? . . . 223

Common Compliance Problems . . . 224

PCB Management . . . 224

Wastewater Discharges . . . 225

Air Emissions . . . 226

Oil Spill Control . . . 226

Hazardous Waste Generation . . . 227

Community Right-to-Know . . . 227

Worker Health and Hazard Communication . . . 228

Employee Safety . . . 228

Underground and Aboveground Storage Tanks . . . 229

Hazardous Materials Storage . . . 230

Drinking Water . . . 230

Solid Waste Disposal . . . 231

Typical Inspection Areas . . . 231

Auditor’s Reminder Checklist . . . 262

Preparing for the Audit . . . 262

Conducting the Audit . . . 264

Chapter 17: Conducting Effective Opening and Closing Conferences . . . 267

Opening Conferences . . . 268

Take Charge of the Meeting . . . 268

Be Organized . . . 268

Discuss Logistics . . . 269

Find Out What’s Happening at the Site . . . 270

Schedule Additional Conferences . . . 271

Address Important Topics . . . 271

Closing Conferences . . . 272

Take Charge of the Meeting . . . 273

Be Organized . . . 273

Be Appreciative but Don’t Bury the Message . . . 274

Set Priorities . . . 274

Minimize Praise for “Acceptable” Performance . . . 275

Respond Professionally to Challenges . . . 275

Focus on Root Causes but Avoid Evaluations of Staff Performance . . . 276

Understand How to Handle Repeat Findings . . . 276

Avoid Comparisons . . . 276

Avoid Guarantees . . . 277

Leave Written Findings . . . 277

Discuss the Next Steps . . . 278

Solicit Site Feedback . . . 278

Chapter 18: Auditing Dilemmas . . . 279

The Management Systems Defense . . . 279

The De Minimis Issue . . . 280

Virtual Compliance . . . 281

Unobtainable Verification . . . 281

Non-Specific Corporate Standards . . . 281

Repeat Findings . . . 283

Just-in-Time Compliance . . . 283

Regulatory Intent . . . 284

Vague Regulatory Definitions . . . 284

Chapter 19: Preparing Quality EH&S Audit Reports . . . 287

Field Preparation . . . 288

Keep the Customer in Mind . . . 288

Look for Underlying Causes . . . 288

Organize Daily . . . 289

Bottom-Line Interviews . . . 289

Develop an Annotated Outline . . . 290

Challenge Each Other . . . 290

Develop a Consistent Debriefing Approach . . . 290

Report Preparation . . . 290

Organize for Monitoring . . . 291

Start Early . . . 291

Establish a Report Format . . . 292

Pay Attention to Repeat Findings . . . 293

Be Careful of “Good Practices” . . . 294

Set Priorities . . . 294

Be Clear and Concise . . . 295

De-emphasize Numbers . . . 297

Use Evidence in the Discussion of Findings . . . 298

Avoid Common Pitfalls . . . 299

Pitfall Examples . . . 299

Report Follow-Up . . . 301

Assure Legal Review of Reports . . . 301

Limit Distribution of the Report . . . 302

Accept No Mistakes . . . 302

Remove Barriers to Efficiency . . . 302

Develop Action Plans . . . 303

Train the Auditors . . . 303

Chapter 20: Environmental Auditing: A Modern Fable . . . 305

The Company . . . 305

The Audit . . . 306

The Beginning . . . 307

The Field Work . . . 308

That Night . . . 309

The Next Day . . . 310

Finishing . . . 311

The Briefing . . . 311

The Report . . . 313

Epilogue . . . 317

Chapter 21: Achieving Quality Environmental Audits: Twenty Tips For Success 319 Do Not Ignore or Underestimate the Need to Prepare for and Plan the Audit and Its Logistics. . . 319

Develop and Maintain a “Living” Agenda throughout the Audit. . . 320

You Will Never Finish So Manage Your Time Wisely. . . 320

Keep a Balance between Records Review, Interviews, and Observation. . . 321

“Things” Will Happen on the Audit. Be Flexible. . . 322

Always Be On Time Even When the Site Staff Are Not. . . 322

Remember Site Staff Will Always Consider Audits a Performance Evaluation. . . 323

In Spite of the Existence of Governmental Regulations and Company Standards, Considerable Judgment Is Still Required. . . 323

Every Country, State, or Region Is Different. . . 323

Learn and Apply the Audit Protocols, but Don’t Forget to Use Your Common Sense and Natural Curiosity. . . 324

Try to Observe Things as They Happen. . . 324

Observe Ancillary Operations. . . 325

Observe, Articulate, and Write, in That Order. . . 326

True and Complete Root-Cause Analysis Can Be Complex, Difficult, and Time Consuming. . . 326

Writing Is the Hardest Part; Developing “Bullet-Proof” Findings Is an Elusive Goal. 327 Write the Findings as You Go. . . 327

Prepare Well for the Opening and Closing Conferences. . . 328

Make Sure the Site Hears the Real Story in the Closing Conference. . . 328

Plan to Be Done When You Depart. . . 328

Enjoy Yourself!!! . . . 328

PART III: SPECIAL AUDITING TOPICS Chapter 22: Property Transfer Assessments . . . 331

Introduction . . . 331

Scope and the ASTM Standard . . . 334

Assessment Team . . . 334

External Contacts . . . 335

The Three Phases . . . 336

Phase I . . . 337

Phase II . . . 344

Phase III . . . 344

Assessment Issues . . . 345

How Do I Know What Rules and Regulations Apply? . . . 345

How Can I Be Sure That the Consultant I Retain Is Qualified? . . . 345

Do I Need a Big Firm or Will an Individual Consultant Suffice? . . . 345

Can I Get a “Clean Bill of Health” Certification? . . . 345

If There Is Some Contamination, How Do I Know If There Is a Problem? In Other Words, “How Clean Is Clean?” . . . 346

Some Deals Develop Quickly. How Much Advance Warning Do I Have to Give the Consultant? . . . 346

What If the Assessment Identifies That Corrective Actions Are Necessary? . . . . 346

What Situations Might Constitute Deal Killers? . . . 347

What Do I Do With the Report If the Deal Is Killed? . . . 348

Who Should Hire the Assessor? . . . 348

What If an Imminent Hazard Is Identified during the Assessment? . . . 349

What Are the General Approaches for Assessing Asbestos? . . . 349

How Is Radon Assessed? . . . 350

Are Wetlands Important? . . . 351

Can Farmland Pose Liabilities? . . . 351

What about Urea Formaldehyde? . . . 352

What about Lead-Based Paint? . . . 352

What about Drinking Water? . . . 353

Conclusion . . . 353

Chapter 23: Top Ten Reasons Why Phase I Environmental Assessment Reports Miss the Mark . . . 355

Failure To Maintain Independence and Objectivity . . . 357

Failure To Define The Exact Scope of Work . . . 358

Use of Conjecture in Report Findings . . . 359

Use of Imprecise Language . . . 359

Failure to Distinguish “Compliance” Findings From “Liability” Findings . . . 360

Documented Sources . . . 361

Failure to State Assumptions Regarding Cost Estimates in Assessment Reports . . . . 362

Disputes Over Disclaimers . . . 364

Failure to Write the Report as a Business-Decision Tool . . . 365

Chapter 24: Waste Contractor Audits . . . 367

Objective and Scope of a TSD Facility Audit Program . . . 369

Internal Programs vs. External Programs . . . 370

Conducting the TSD Facility Audit . . . 372

Pre-Audit Preparation . . . 372

Special Pre-Audit Considerations . . . 375

Selecting the Audit Team . . . 378

The On-Site Audit . . . 379

The TSD Facility Audit Report . . . 383

Conclusion . . . 385

Chapter 25: Waste Minimization or Pollution Prevention Audits . . . 387

Why a Pollution Prevention Focus? . . . 387

The General Approaches . . . 388

Limitations and Constraints . . . 389

Methodology . . . 389

Examples of the Presence of a Waste Minimization Effort . . . 393

Chapter 26: Evaluating Management Systems on EH&S Audits . . . 395

Why Evaluate Management Systems? . . . 395

What is a Management System? . . . 396

How Do You Do It? . . . 398

Practical Tips . . . 400

Why is It So Hard? . . . 401

Conclusion . . . 402

Chapter 27: International EH&S Audits . . . 403

Role of Corporate Management . . . 405

Design of International Audit Programs . . . 406

Two-Phased Approach . . . 407

Audit Standards and Criteria . . . 407

Conducting International Audits . . . 410

On-Site Activities . . . 412

Post-Audit Activities . . . 412

Summary of Key Challenges in International Audits . . . 413

APPENDICES Appendix A: References . . . 419

Appendix B: Federal Register Notes . . . 423

Appendix C: Sample EPCRA Audit Protocol . . . 455

Appendix D: Problem Solving Exercises . . . 477

Appendix E: Summary of Audit Programs . . . 555

Appendix F: Model EH&S Audit Program Manual . . . 581

Appendix G: Model Pre-Audit Questionnaires for EH&S Audits . . . 615

Appendix H: Model EH&S Audit Opening Conference Presentation . . . 645

Appendix I: Model Environmental Audit Report . . . 653

Appendix J: Model Environmental Audit Appraisal Questionnaire . . . 671

Appendix K: Model Management Presentation . . . 675

Figure 1.1 Growth of Environmental Regulations . . . 5

Figure 1.2 Comparing U.S. EPA and OSHA Staff Size . . . 5

Figure 1.3 U.S. EPA’s Short-Term Agenda . . . 6

Figure 1.4 State Regulatory Stringency . . . 7

Figure 1.5 Concentration of Lawyers in Developed Countries . . . 7

Figure 1.6 1998 TRI Reporting – Total Releases by State . . . 8

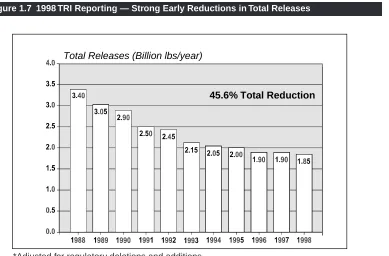

Figure 1.7 1998 TRI Reporting – Strong Early Reductions in Total Releases . . . 9

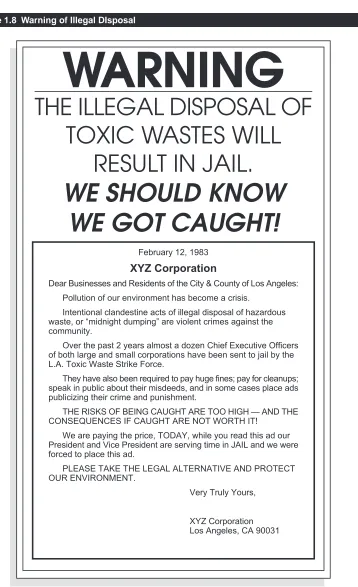

Figure 1.8 Warning of Illegal Disposal . . . 12

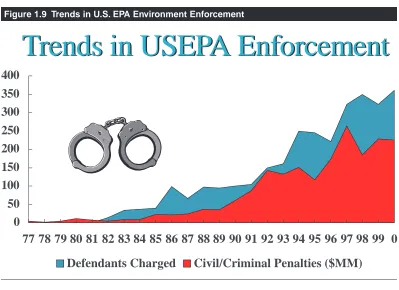

Figure 1.9 Trends in U.S. EPA Environmental Enforcement . . . 13

Figure 1.10 Incidents at Walt Disney Corporation . . . 13

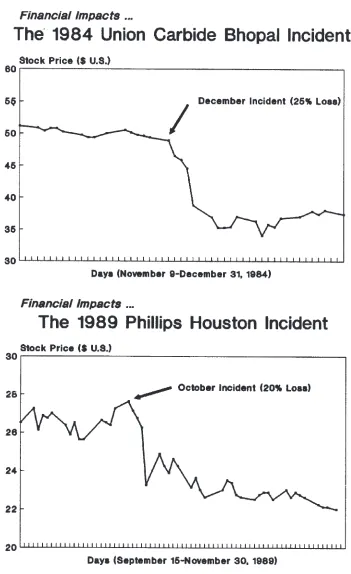

Figure 1.11 Financial Impacts of Industry Incidents . . . 14

Figure 1.12 Common External Expectations for Environmental Audit Programs . . . 22

Figure 2.1 States with Audit Privilege and Immunity Laws: June 8, 2000 . . . 39

Figure 2.2 States with Self-Disclosure Policies: June 8, 2000 . . . 40

Figure 4.1 Elements of an Audit Program . . . 66

Figure 4.2 Why Audit? Industry’s Response to Audit Program Objectives . . . 69

Figure 4.3 Industry’s Response to Audit Confidentiality . . . 72

Figure 4.4 Industry’s Response to Frequency of Audits . . . 74

Figure 4.5 Assessing Risk in a Multi-Plant or Multi-Unit Setting . . . 76

Figure 4.6 Sample Site Visit Schedule . . . 77

Figure 4.7 Example Site Environmental Audit Process Timeline . . . 80

Figure 5.1 Corporate Performance Judged beyond Compliance . . . 90

Figure 5.2 Consequences of the Exxon Valdez Incident . . . 92

Figure 5.3 Environmentalists on Board of Directors . . . 103

Figure 5.4 Environmental Audit Benchmarking Study . . . 106

Figure 6.1 Questionnaire to Determine the Adequacy of Audit Resources and the Level of Cooperation of the Audit . . . 112

Figure 6.2 Sample EMS Audit Report Introduction . . . 114

Figure 7.1 Summary of the Review of 20 Environmental Audit Programs . . . 120

Figure 7.2 Standard Environmental Audit Methodology . . . 124

Figure 8.1 Total Quality Management—The Benchmarking Process . . . 130

Figure 8.2 Competitor Financial Evaluation . . . 131

Figure 13.1 Audit Reporting Process Organizational Responsibilities . . . 173

Figure 13.2 Audit Reporting Process Critical Data Elements for Tracking . . . 175

Figure 14.1 Key Audit Program Planning Issues . . . 180

Figure 14.2 Compliance Monitoring . . . 186

Figure 15.1 Model Pre-Audit Checklist . . . 195

Figure 15.2 Typical Compliance Areas on an EH&S Audit . . . 200

Figure 15.3 Sample Itinerary for an Audit . . . 202 Figure 15.4 EH&S Compliance Audit Program Example Documents to Review . . . . 208 Figure 15.5 Inspecting Remote Areas . . . 213 Figure 15.6 Inspecting Buildings . . . 215 Figure 15.7 Timing Inspections . . . 215 Figure 15.8 Inspecting the Fence Line . . . 216 Figure 15.9 Emergency Response Drills . . . 217 Figure 15.10 Auditing Sampling Procedures . . . 218 Figure 15.11 Selecting a Sample Size on EH&S Audits . . . 220 Figure 16.1 In-Service PCB Transformer . . . 232 Figure 16.2 PCB Transformers Out of Service and Awaiting Disposal . . . 234 Figure 16.3 Wastewater Treatment Facilities . . . 236 Figure 16.4 Stormwater Discharges . . . 238 Figure 16.5 Hazardous Waste Accumulation in Drums . . . 240 Figure 16.6 Hazardous Waste Storage Facility . . . 242 Figure 16.7 Aboveground Oil Storage Tank . . . 244 Figure 16.8 Aboveground Storage Tank Seal Inspection . . . 246 Figure 16.9 Solid Waste Incinerator . . . 248 Figure 16.10 Solvent Metal Cleaner . . . 250 Figure 16.11 Pesticide Storage Facility . . . 252 Figure 16.12 Hazardous Materials Dispensing Area for Shop Use . . . 254 Figure 16.13 Flammable/Combustible Materials Storage Facility . . . 256 Figure 16.14 Solid Waste Disposal Facility . . . 258 Figure 16.15 Drinking Water Sampling Point . . . 260 Figure 18.1 Aboveground Storage Tank with Horizontal Fill Line Drawn . . . 280 Figure 18.2 Diesel Oil Tank without Secondary Containment . . . 282 Figure 18.3 Inspecting a Hazardous Waste Accumulation Area . . . 283 Figure 19.1 EH&S Audit Findings Form . . . 297 Figure 22.1 Approach to Conducting Site Environmental Assessments . . . 336 Figure 22.2 Potential Risks Posed by Real Estate Transactions . . . 339 Figure 24.1 Sources for Obtaining the Pre-Audit Information . . . 374 Figure 24.2 Areas Most Often Addressed in Commercial TSD Facility Audit

It has been five years since Government Institutes published the seventh edition of

Environmental Audits. Since that time, we have continued to see the Environmental,

Health, and Safety auditing field mature and blossom. During the preparation of the previous edition, the ISO 14000 Standards and Guidelines were still a year away from issuance, the U.S. EPA had only just released its 1995 Self-Policing Policy to say nothing of the Agency’s 2000 Policy, and there was no such thing as a Board of Environmental, Health, and Safety Auditor Certifications. There were also only 13,100 pages of U.S. Federal environmental regulations then; there are now over 17,000 pages, which is a growth of 30 percent.

As a consequence, the seventh edition, like all previous editions, was becoming very outdated. This was problematic for me as the book is the principal tool used in the ABS Group, Government Institutes Division’s Environmental, Health, and Safety Audits training course, which I have been leading since 1983.

I have always said to the course attendees that once the supplementary materials become thicker than the course text, then I know it’s time for a new edition. Well, for the past couple of years that has been the case as we’ve attempted to keep the course current. However, it has taken me these same two years to store up enough energy to put out another edition. I started planning for this edition in 1998. Those of you who have attempted to write and edit a technical book while maintaining a full-time job and family responsibilities will know why it took a while to mobilize. The work on this book was done late at night and on weekends, and not always in the United States.

The eighth edition maintains the same basic three-part structure of the seventh: Managing a Program, Conducting the Audit, and Special Auditing Topics. As in the past, the new edition stands alone as a complete document; where information from the previous edition was determined to be no longer relevant, this material was re-moved. Moreover, no chapter in the eighth edition went untouched as we attempted to improve the quality and provide the most current information.

There are now twenty-seven chapters in the book as opposed to twenty-five. We have removed one chapter and added three new chapters: Chapter 6 on ISO 14000 and its Potential Effect on Auditing Programs, Chapter 18 on Auditors’ Dilemmas, and Chapter 21 on Twenty Tips for Conducting Successful Audits. Yet, probably the real added value in the eighth edition is the audit tools we have added, principally in the Appendices. These include:

· A model EH&S Audit Program Manual

· A new model Pre-Audit Questionnaire

· A model Pre-Audit Checklist

· A model EH&S Audit Opening Conference Presentation

· A model Environmental Audit Report (reflective of ISO 14000 expectations)

· A model EH&S Audit Appraisal Questionnaire

· A model Management Report.

These tools can be tailored to fit any EH&S audit program and represent a “fast-start” kit for anyone developing a program from scratch.

Finally, throughout the text we discuss new developments in information gen-eration and availability, especially Internet sites, which can add real value to a pro-gram.

Through the efforts of my co-authors, we believe we have addressed the issues currently impacting EH&S audits and audit programs. It is a very dynamic setting in late 2000 and further changes likely are ahead of us.

AND PRINCIPAL AUTHOR

Mr. Lawrence B. Cahill, CPEA is a Principal in ERM’s Business Integration Group located in Exton, PA. Mr. Cahill has over twenty-five years of professional EH&S experience with industry and consulting. Principally for Fortune 500 Companies such as DuPont, Exxon, BFGoodrich, Colgate-Palmolive, Hercules, Bristol-Myers Squibb, TRW, and Hughes Aircraft, he has developed, evaluated, and certified audit programs; conducted hundreds of audits; and trained literally thousands of people in auditing skills all over the world, including Asia-Pacific, South America, Africa, Europe, and North America. He has provided an “auditor’s opinion letter” formally certifying the efficacy of EH&S audit programs for DuPont, Eastman Kodak, Occi-dental Petroleum, TRW, Honeywell, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among others. These letters have routinely appeared in the companies’ annual environmental reports.

Mr. Cahill has been awarded Distinguished Instructor status by Government Institutes. He has taught Government Institutes’ Environmental, Health and Safety Audits course since 1983. He is a member of the Environmental, Health and Safety Auditing Roundtable (EAR) and was on the original Board of Directors of the Board of Environmental, Health and Safety Auditor Certifications (BEAC). He is a Certi-fied Professional Environmental Auditor, with Master Certification.

Mr. Cahill holds a B.S. in mechanical engineering from Northeastern Univer-sity, an M.S. in environmental health engineering from Northwestern UniverUniver-sity, and an M.B.A. in Public Management from the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. He previously was a Project Engineer with Exxon Re-search and Engineering where he audited plants in the U.S., Canada, and Europe.

RAYMOND W. KANE Independent Consultant

Environmental Management Consulting

Mr. Kane wrote all or parts of Chapters 5, 15, 16, and 23.

Mr. Kane is currently senior vice president at Marsh Risk Consulting. He deals with EH&S compliance audits, audit program development, third-party review of EH&S audit and management programs, EH&S training, ISO 14000 environmental man-agement consulting, and environmental due diligence. Previously, Mr. Kane was a consultant with Environmental Management Consulting in Philadelphia, PA, and vice president at McLaren/Hart Environmental Engineering Corporation. There he developed and conducted major environmental audit and compliance programs for private industry and federal organizations such as the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Air Force. Mr. Kane received his B.S. and M.S. in Civil/Environmental Engineering from Villanova University and served for four years in the U.S. Navy as a submarine officer.

MARC E. GOLD Partner

Manko, Gold & Katcher

Mr. Gold co-authored Chapter 3.

Marc E. Gold is a founding partner of Manko, Gold & Katcher, L.L.P., a twenty-lawyer firm that concentrates its practice exclusively in environmental law. For-merly, Mr. Gold served as a Section Chief in the Legal Branch of the U.S. EPA, Region 3, and was a partner in the Environmental Department of a major Philadel-phia law firm. In addition, Mr. Gold was an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Temple University’s School of Engineering where he taught environmental regulation. Mr. Gold has more than twenty years of experience in environmental law. His practice focuses on all aspects of environmental regulation and counseling covering hazard-ous waste, air and water pollution, and site remediation issues. Mr. Gold has been involved in several multi-facility environmental audits and has participated in the development of corporate environmental policies and procedures. Mr. Gold received his law degree from Villanova University School of Law and his B.A. from The American University.

MICHAEL M. MELOY Partner

Manko, Gold & Katcher

Mr. Meloy co-authored Chapter 3.

Michael M. Meloy is a partner at Manko, Gold & Katcher, LLP, a law firm concen-trating in environmental and land use law. Mr. Meloy brings both a legal and engi-neering background to bear in regularly advising clients with respect to a broad spectrum of environmental regulatory and litigation issues. He has been actively involved in the development and implementation of the residual waste and hazard-ous waste programs in Pennsylvania. He has also been actively involved in the development of self-evaluative privilege legislation for Pennsylvania. In addition, as part of his practice, Mr. Meloy has advised clients regarding health and safety issues arising under the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Mr. Meloy is a mem-ber of the Natural Resources, Energy, and Environmental Law Section, American Bar Association; the Environmental, Mineral, and Natural Resources Section, Penn-sylvania Bar Association; and the Environmental Law Committee of the Philadel-phia Bar Association. Mr. Meloy earned his bachelor’s degree in civil engineering, summa cum laude, from the University of Delaware in 1980. He was admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar in 1983 after graduating cum laude from Harvard Law School.

BRIAN P. RIEDEL

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Mr. Riedel wrote Chapter 2.

JAMES C. MAUCH Vice President

Vista Environmental Information, Inc.

Mr. Mauch co-authored Chapter 22 with Mr. Cahill.

Mr. Mauch was vice president for Vista Information Solutions, Inc., in Louisville, KY. He was also an attorney and was in private practice for five years with a Mid-west general practice and litigation law firm. His practice involved trial work and commercial litigation, and focused in part on environmental and mineral rights is-sues affecting land use transactions. While at Vista, Mr. Mauch was involved in federal legislative initiations and published articles on the appropriate standards for Phase I environmental real estate assessments. Mr. Mauch was an active member of ASTM’s E-50.02 subcommittee, which developed the Site Assessment Standards, and he was chairman of the Public Records Task Group of that subcommittee.

LORI BENSON MICHELIN

Manager of Knowledge Management Colgate-Palmolive Company

Ms. Michelin co-authored Chapter 21 with Mr. Cahill.

Lori Benson Michelin has more than twelve years of professional environmental experience. Ms. Michelin works for Colgate-Palmolive Company and was instru-mental in developing and implementing Colgate-Palmolive’s EH&S Audit Program, which is now under way in every region of the world. She served in a dual role as the Corporate Audit Program manager and Environmental Engineering Manager. Her environmental engineering group provided direct technical support to new and ex-isting manufacturing facilities in key areas such as wastewater treatment, air per-mits, and waste management. Prior to joining Colgate-Palmolive, Ms. Michelin worked as an EH&S Manager for Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc. She also worked as an environmental consultant on projects related to waste collection and treatment, water distribution, and land use while she was employed at BCM Engineers and Carrol Engineering. Ms. Michelin received her M.S. in Civil and Environmental Engineering from Villanova University and her B.S. in Civil Engineering from Penn-sylvania State University. She has a Professional Engineering license.

THOMAS R. VETRANO Principal

ENVIRON Corporation

Mr. Vetrano contributed to both Chapters 24 and 27.

I wish to thank the contributing authors for their efforts in delivering a quality prod-uct on time. Well, at least in delivering a quality prodprod-uct. Working with the staff at ABS Group / Government Institutes Division in preparing the manuscript was a pleasure. All the authors had to do was email rough electronic versions of the mate-rial to Government Institutes and, believe me, that was challenge enough. Thank you Charlene at Government Institutes for the encouragement (or was it harass-ment?) it took to produce the eighth edition. Nothing gets done well without help.

3

PERSPECTIVES IN

EH&S AUDITING

Eyes are more accurate witnesses than ears.

– Heraclitus, c. 540-480 B.C.

WHY AUDIT?

Managing compliance in today’s regulatory setting has become an overwhelming exercise, involving more and more regulations, and affecting more and more orga-nizations. In the United States, we have gone well beyond the straightforward regu-lation of air emissions and wastewater effluents, which were the prevalent com-mand and control initiatives in the legislation and regulations of the 1970s. Hazardous wastes and hazardous materials are now tightly controlled, and their discharges are freely and openly reported through community and worker right-to-know regula-tions. The U.S. can no longer assume that it is at the leading edge of environmental regulation. Many countries have adopted U.S. regulations as a baseline and have built an even more stringent platform from there.

The traditional approach of regulating only major industry groups has also long passed us by. In this day and age, environmental rules affect neighborhood dry clean-ers, liquor stores, auto parts stores and body shops, amusement parks, and, in some states, your local supermarket.

Even more disturbing, we find no safe harbor from these complicated and per-vasive issues while sitting at home. Consider the following:

■ Could your home contain friable asbestos? Although asbestos insulation

was outlawed around 1974, the U.S. EPA estimates that thousands of public buildings and innumerable homes still contain asbestos.

■ Was your home built over an abandoned landfill? Love Canal is the

■ Could there be radon in the basement? U.S. EPA has reported that

mil-lions of U.S. homes are potentially tainted with unsafe radon levels. Scien-tists estimate that thousands of lung cancer deaths a year may be caused by radon.

■ Could your drinking water supply be contaminated? A study by the Center

for Responsive Law found that nearly one in five public drinking water sys-tems is contaminated with chemicals, some of them toxic. Many in-home supplies are contaminated with excessive levels of lead, abraded from the lead solder used to connect copper piping.

■ Could fluorescent lights be a source of PCBs and mercury? Light

bal-lasts manufactured before 1976 will likely contain PCBs. The tubes them-selves can contain trace amounts of mercury.

Growth of Regulations

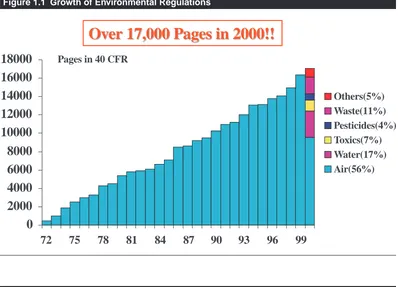

This continuous emergence of new environmental risks has resulted in the regular enactment of laws designed to protect both public health and the environment. As Figure 1.1 demonstrates, we have seen a dramatic growth in federal environmental regulations, even during periods of “regulatory reform.” National environmental regulations under Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) now total over 17,000 pages and have grown by over 50 percent in the 1990s alone! Health and safety regulations promulgated under Title 29 add another 2,700 pages. Can 20,000 total pages be far off? Well interestingly enough, there could be a barometer that might answer this question. If we review the statistics reported by both the U.S. EPA and OSHA, we note that there is roughly one employee or full-time equivalent per page of regulation at each agency (see Figure 1.2). Does this tell us anything? Perhaps.

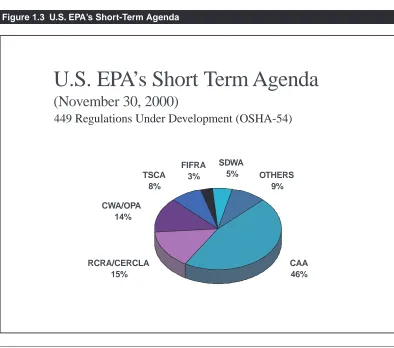

The stifling federal regulatory oversight is not likely to abate for some time, even with the new, more cooperative approach to regulation that evolved in the mid-1990s. In November 2000 the U.S. EPA reported in its short-term agenda that it had some 449 regulations under development, revision, or review (see Figure 1.3). Al-most half of these are regulations to be promulgated under the Clean Air Act, argu-ably one of the most complex pieces of legislation ever passed by Congress. Over this same time period, OSHA has reported that it is expected to add another 54 regulations.

0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 12000 14000 16000

18000 Pages in 40 CFR

Others(5%) Waste(11%) Pesticides(4%) Toxics(7%) Water(17%) Air(56%)

Over 17,000 Pages in 2000!!

Over 17,000 Pages in 2000!!

99 96 93 90 87 84 81 78 75 72

Comparing U.S. EPA and OSHA

Staff Size

F T E (2 0 0 1 F Y B udg e t)

1 8,050 2 ,3 84

[image:38.504.50.455.59.655.2]E P A O SH A

Figure 1.1 Growth of Environmental Regulations

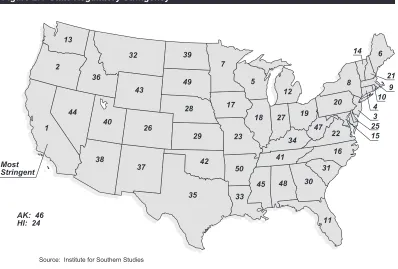

[image:38.504.54.452.86.373.2]have been, adopted by other states. For organizations with facilities in more than one state, compliance assurance can be difficult if not impossible. As can be seen in Figure 1.4, states will vary in their regulatory stringency; thus, it is typically quite a challenge to stay current on regulations promulgated in multiple states. With the proliferation of community right-to-know legislation in the last few years, local fire departments and county agencies have become players in the game.

[image:39.504.55.449.71.419.2]Moreover, the regulatory environment varies significantly from country to try. Figure 1.5 begs the question: Are there fewer lawyers per capita in other coun-tries because the councoun-tries are less litigious by nature, or are other councoun-tries less litigious because they have fewer lawyers? The United States is known to be a very litigious society with an overwhelming regulatory framework. Other countries have a more cooperative relationship between the regulators and the regulated, and are much less litigious. For multi-national companies, the need for different rulebooks can be very challenging.

Figure 1.3 U.S. EPA’s Short-Term Agenda

U.S. EPA’s Short Term Agenda

(November 30, 2000)

TSCA 8%

RCRA/CERCLA 15% CWA/OPA

14%

OTHERS 9%

CAA 46% FIFRA

3%

SDWA 5%

Concentration of Lawyers

in Developed Countries

3 07 1 02

8 2 1 2

0 5 0 1 00 1 50 2 00 2 50 3 00 3 50 L a w ye r s pe r 1 00,000

[image:40.504.55.453.91.360.2]J apan G e r many U .K . U .S.

Figure 1.4 State Regulatory Stringency

[image:40.504.59.453.415.667.2]Growth in Visibility

It was not so long ago that a company’s EH&S information was known only to them and to the regulatory agencies. This is no longer true. With the advent of community and worker right-to-know legislation, and the Internet, EH&S data are available to all citizens with the click of a mouse. For example, the three following Internet sites provide detailed information on a facility’s historical compliance:

• www.epa.gov/enviro – Provides U.S. EPA historical data on all

envi-ronmental media for each regulated facility.

• www.scorecard.org – Developed by the Environmental Defense Fund,

provides historical data on Community Right-to-Know Toxic Release Inventory Facility Reports.

• www.osha.gov/oshstats – Provides OSHA inspection data for each

in-spected facility.

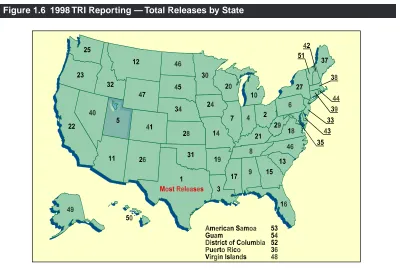

Information can be gathered and analyzed quite easily using available data. For example, Figures 1.6 and 1.7 provide interesting state-by-state and year-by-year comparisons of Toxic Release Inventory data. This is only the “tip of the iceberg.” There is little that is not known or that could not be obtained about EH&S compli-ance at a given facility.

1998 TRI Reporting

[image:41.504.54.454.393.664.2]1998 TRI Reporting

Strong Early Reductions in Total Releases*

* Adjusted for regulatory deletions and additions

* Adjusted for regulatory deletions and additions

45.6% Total Reduction

Total Releases (Billion lbs/year)

Growth in Enforcement

In this regulatory setting, one can only wonder if “fail-safe” management of com-pliance is, indeed, an achievable objective. Yet, the penalties for not complying are far too intimidating to risk applying anything but extreme diligence towards meet-ing standards and applymeet-ing good management practices. Civil penalties of up to $25,000 per day are common in most statutes.

In addition, the U.S. EPA has reemphasized its enforcement role and has moved toward a policy of taking enforcement action against corporate officials as well as their companies. The following cases are some of the more unique and interesting examples of that policy reported by the U.S. EPA in 1998.1 Note that several of the

cases actually involve companies that were in the business of environmental man-agement and protection.

■ GTE Corporation. In January 1998 the largest settlement under the U.S.

EPA’s Audit Policy (see Chapter 2) was reached when GTE agreed to re-solve 600 violations at 314 facilities in 21 states. The company paid a fine of

1 Taken from U.S. EPA’s Enforcement and Compliance Assurance Accomplishments Report—FY

[image:42.504.68.457.79.335.2]1998, June 1999.

Figure 1.7 1998 TRI Reporting — Strong Early Reductions in Total Releases

about $50,000; the U.S. EPA waived another $2.38 million in potential pen-alties. However, the U.S. EPA did undertake an enforcement initiative against ten other telecommunications companies, essentially GTE’s competitors, to determine if similar violations existed at their sites.

■ United States v. Louisiana Pacific Corporation. The Louisiana Pacific

Cor-poration (LPC) operated a wood products plant in Colorado. An indictment alleged that the plant manager and plant superintendent violated the Clean Air Act and committed mail and wire fraud. The Company was convicted of 18 felony counts and fined $36.5 million. The plant manager was sentenced to ten months of jail time and the superintendent, six months.

■ United States v. Safewastes, Inc. In 1993 the Sacramento, California Fire

Department inspected a warehouse which led to the discovery of illegally stored hazardous wastes and rocket motors, warheads, 17,000 artillery shells, and 7,500 pounds of explosives. The two principals involved were charged with illegal storage and transportation of hazardous wastes, among other firearms infractions, and were given 21 and 51 months of jail time.

■ United States v. Hess Environmental Laboratories, Inc. Investigations by

federal and state regulatory agencies revealed that this lab in Pennsylvania was providing fraudulent analyses of environmental samples to its custom-ers. The lab was fined $5 million and the director was sentenced to 12 months of jail time. In May of 1997 the lab closed and terminated its business.

■ United States v. Barry Shields, et al. The IEMC Environmental Group was

contracted to remove asbestos-containing materials from the Hess Depart-ment Store in Louisville. As a result of improper removal, the storeowner was ordered to conduct an emergency cleanup, which cost about $1 million. The IEMC project manager was sentenced to 51 months in prison and the onsite supervisor, ten months.

■ United States v. Warner Lambert Company, Inc. This company was

con-victed of falsifying discharge monitoring reports in 1998. The receiving waters were used by poor area residents for drinking water and recreational pur-poses. The company was fined $3 million and the plant manager was sen-tenced to 21 months in prison.

■ United States. v. Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines, Ltd. In October 1994, the

million in fines and was convicted of witness tampering, destruction of evi-dence, and conspiracy.

■ United States v. City Sales, Ltd., et al. In 1993 and 1994, City Sales, a

Cana-dian auto parts dealership, illegally imported 246 tons of CFC-12 into the U.S. They never possessed the CAA consumptive allowances and made false declarations on import invoices. The City Sales owner was sentenced to 15 months in prison. His wife was also convicted.

Placement of notices in local newspapers is another approach that regulatory agencies are using with increasing frequency. As an example, Figure 1.8 is a copy of a full-page notice placed in the Sunday Los Angeles Times, as mandated by the Los Angeles Toxic Waste Strike Force.

The sum total of the EPA’s enforcement efforts is shown in Figure 1.9. Note that the amount of fines and the number of defendants charged have grown substantially over the past 20 years. No company, no matter how apparently innocuous its opera-tions, is immune. Figure 1.10 notes the Walt Disney Corporation’s record in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

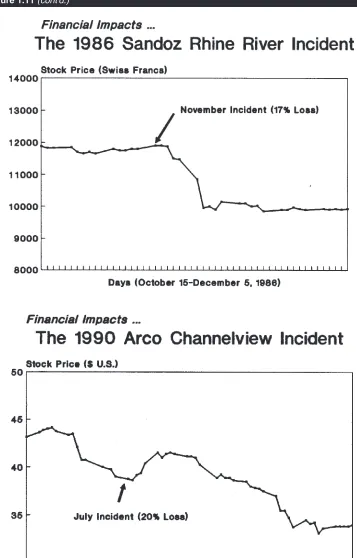

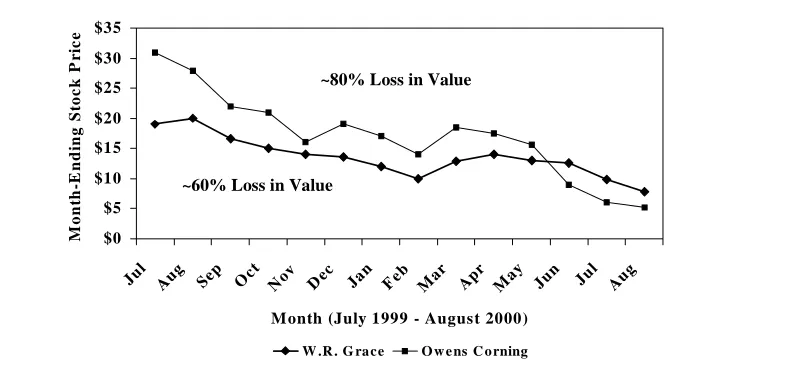

As if all this weren’t enough to heighten the anxiety of corporate managers, they may also face the ire of stockholders if the company’s stock price is adversely af-fected by compliance problems. This is a real risk, as indicated by Figure 1.11, which shows the short-term price drops of four public companies suffering through environmental incidents. The classic case in this regard is Union Carbide’s Bhopal tragedy in late 1984. The impacts of more recent asbestos claims are just as substantial.

IMPACT ON THE REGULATED COMMUNITY

What are the implications of these policies and trends for management? With the high probability of continued controversy and complexity in the EH&S arena, it is very important to avoid complacency and to pay attention to compliance matters. Management’s ability to anticipate and respond to government and private actions aimed at addressing real or perceived EH&S problems must remain undiminished. Yet, corporate outlays for environmental management, including those for staffing, generally have been reduced, as have expenditures for many other business activi-ties in the competitive economic climate of the last decade. Thus, many companies may be less than ideally prepared to face a future regulatory environment that will continue to be complex and onerous.

Incidents at

Walt Disney Corporation

Date

Incident

Fines

7/90

Waste Disposal

$550,000

4/90

Sewage Discharge

$300,000

1/90

Vulture Kill

$10,000

1989

PCB Transport

$2,500

1988

Waste Storage

$150,000

[image:46.504.53.452.74.364.2]Totals

$1,012,500

Figure 1.9 Trends in U.S. EPA Environment Enforcement

Figure 1.10 Incidents at Walt Disney Corporation

Trends in USEPA Enforcement

Trends in USEPA Enforcement

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400

77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98

Defendants Charged Civil/Criminal Penalties ($MM)

The 1999 Asbestos Class

The 1999 Asbestos Class

-

-

Action Lawsuits

Action Lawsuits

and Settlement Agreements

and Settlement Agreements

$0 $5 $10 $15 $20 $25 $30 $35

Jul Aug Sep Oc t

No v

De c

Jan Feb Ma r

Ap r

Ma y

Jun Jul Au g

Month (July 1999 - August 2000)

M

o

nt

h-E

ndi

ng

St

oc

k P

r

ic

e

W .R . G ra ce O w e ns C o rning

~60% Loss in Value

~80% Loss in Value

latory requirements, good management practices, and corporate policies and proce-dures at all facilities.

EVOLUTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL AUDITING

As a separate and distinct compliance management tool, environmental auditing had its beginnings in the late 1970s and early 1980s. These beginnings were stimu-lated principally by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) actions against three companies: U.S. Steel (1977), Allied Chemical (1979), and Occidental Petro-leum (1980).2 The SEC required each of these public companies to undertake

cor-porate-wide audits to determine accurately the extent of the environmental liabili-ties they faced. In essence, the SEC believed that each company was vastly understating its liabilities in its annual report to stockholders. Since that original SEC audit, each company has had an effective environmental audit program in place. In the 1990s, the SEC once again raised this issue of inaccurate reporting of environmental liabilities by public companies in annual reports. Most recently, the

2 SEC v. Allied Chemical Corp., No. 77-0373 (D.D.C., March 4, 1977); SEC v. U.S. Steel Corp.,

(1979-1980 Transfer Binder) Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) 82,319 (1979); SEC v. Occidental Petroleum

Corp., (1980 Transfer Binder) Fed. Sec. L. Rep. (CCH) 82,622 (1980).

[image:49.504.56.456.162.352.2]SEC has stated that it believes companies are not portraying their potential Superfund liabilities properly. It is possible that another round of SEC actions could occur in the near future, unless the perceived systemic discrepancies are remedied.

On the heels of the SEC audits came the implementation of major hazardous waste rules that were promulgated in the late 1970s and put into effect beginning in 1980. These rules were comprehensive, administratively complex, and potentially costly if not adhered to. Because of the nature of the industry, the large chemically intensive corporations were the first to develop audit programs to better respond to these rules. In recent years, many Fortune 500 diversified manufacturing companies have begun to adopt the concept. Even government agencies have seen the light and are developing programs that focus both on compliance for operating facilities and defining liabilities where property is bought or sold.

Today, in the new millenium, environmental auditing has reached a certain level of maturity. Applicability has spread beyond the basic chemical industry to all types of industries and even government agencies.3 Even simple properties are

undergo-ing audits or assessments prior to sale. Additionally, most generators of hazardous waste are auditing the sites to which their wastes are being transported for handling and disposal by third parties.

EH&S AUDITING ORGANIZATIONS

Although now a widespread practice, auditing is still an evolving discipline. As a result, several associations have been organized to further the profession of EH&S auditing. Two of the better known are discussed below. The discussions are based on descriptions provided by the associations.

EH&S Auditing Roundtable

The EH&S Auditing Roundtable (EHSAR) is a professional organization dedicated to furthering the development and professional practice of environmental auditing. The EAR dates back to January 1982, when managers of several environmental audit programs met informally to discuss their auditing programs and practices, as well as policy and regulatory actions related to auditing.

The original group soon increased to ten managers who held quarterly meetings during 1982 and 1983. Meetings were opened to all interested persons in September 1984, with the original ten members serving as the organization’s first steering com-mittee. At that time, the organization adopted the name Environmental Auditing Roundtable and developed a statement of purpose and organizational principles.

3 Government agencies certainly have reason to pause over environmental contamination. It has been

In June 1987, EAR participants adopted a code of ethics and bylaws that, among other things, established general membership criteria and a five-member board of directors elected by the membership at large. Following peer review and vote by the membership, EAR adopted Standards for the Performance of Environmental Audits in 1993.

Most EAR members are practicing EH&S auditors with extensive field experi-ence. While EAR focuses primarily on meeting the needs of industry, membership is open to anyone with a professional interest in the practice of EH&S auditing. Since June 1984, EAR has continued to hold regular national and regional meet-ings. The EAR has more than 800 members. For more information about EAR, contact:

Environmental, Health & Safety Auditing Roundtable 15111 N. Hayden Road

Suite No. 160355

Scottsdale, AZ 85260-2555 Phone: (480) 659-3738 Fax: (480) 659-3739 http://www.auditear.org

The Board of EH&S Auditor Certifications

In 1997 the Board of EH&S Auditor Certifications (BEAC) was established as a joint venture of the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) and the EH&S Auditing Roundtable to provide certification programs for the professional practice of EH&S auditing. The BEAC is an international, independent, non-profit association dedi-cated to advancing the professional development of the individual EH&S auditor and the EH&S auditing profession. BEAC offers three Certified Professional Audi-tor (CPEA) designations: EMS 14000 Plus, environmental compliance, and health and safety. For more information about the BEAC, contact:

Board of EH&S Auditor Certifications 249 Maitland Avenue

Altamonte Springs, FL 32701-4201 Phone: (407) 831-7727

Fax: (407) 830-7495 http://www.beac.org

DEFINING ENVIRONMENTAL AUDITS

to do with the fact that audit programs are typically designed to meet one or more of the following objectives:

■ Assuring compliance with regulations ■ Determining liabilities

■ Protecting against liabilities for company officials ■ Fact-finding for acquisitions and divestitures ■ Tracking and reporting of compliance costs ■ Transferring information among operating units ■ Increasing environmental awareness

■ Tracking accountability of managers.

Yet, within these broad boundaries, definitions can be framed. The U.S. EPA defines environmental auditing as “a systematic, documented, periodic and objec-tive review by regulated entities4 of facility operations and practices related to meeting

environmental requirements.”5

An alternative definition is that audits can be said to verify the existence and use of:

Adequate...Systems...Competently...Applied.

Simply put, an audit program is first and foremost a verification program. It is not meant to replace existing environmental management systems at the corporate (e.g., regulatory updating), division (e.g., capital planning for pollution control ex-penditures), or plant (e.g., NPDES discharge monitoring) levels. Indeed, the pro-gram should be designed to verify that these environmental management systems do, in fact, exist and are in use. These systems, whether they are to assure compli-ance or define liabilities, need to be adequate, in that they should acknowledge and respond directly to the regulatory and internal requirements that define compliance or liability.

The systems should also be applied, meaning that procedures are not simply “bookshelf exercises,” out-of-date and out-of-use before the ink dries. Finally, the systems must be applied competently. All plant managers, environmental coordina-tors, and unit operators must have an awareness of environmental compliance, and conduct their responsibilities accordingly.

4 “Regulated entitites” include private firms and public agencies with facilities subject to

environ-mental regulation. Public agencies can include federal, state, and local agencies as well as special-purpose organizations such as regional sewage commissions.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES

Like most anything in life, audit programs can be characterized by both advantages and disadvantages. On the positive side, audits can result in a number of significant benefits, including:

■ Better compliance ■ Fewer surprises ■ Fewer fines and suits

■ Better public image with the community and regulators ■ Potential cost savings

■ Improved information transfer ■ Increased environmental awareness.

However, these benefits can be offset by some real and potential costs (which will be discussed in more detail in other chapters in this book):

■ The commitment of resources to run the program ■ Temporary disruption of plant operations

■ Increased ammunition for regulators

■ Increased liability where one is unable to respond to audit recommendations

involving significant capital expenditures.

The last two disadvantages raise a special issue associated with EH&S audits. Even where programs are operated under legal protections (e.g., attorney-client privi-lege) as discussed in another chapter, there is a chance that audit reports could be “discovered” in a legal proceeding. Thus, it is vital management understands that if a program is initiated, the company must be serious about fixing the problems that are identified in the reports. Otherwise, the report could be most incriminating in a court case or administrative proceeding.

Notwithstanding these drawbacks, most firms, faced with the question of whether or not to undertake an audit program, have opted to do so. The general theory is that in this day of increased litigation and possible criminal suits, it is better to know your liabilities than to remain oblivious to them. As stated some time ago by a former U.S. EPA General Counsel: “Management ignorance is no defense!”6

6 R.V. Zener, In Environmental Reporter, Bureau of National Affairs, Current Developments (June

TRENDS IN EH&S AUDITING

In the past few years, a number of interesting trends have surfaced within the envi-ronmental auditing discipline. These include:

■ A Push for Standards. With the development of several professional

orga-nizations, as described earlier in this chapter, we have seen a push by some segments of the auditing profession towards the development of standards and possibly national and international registration or certification. As dis-cussed in a later chapter, standards such as ISO 14000 and the European Eco-Management and Audit Scheme and the like are proliferating. The thought is that standards will help to improve the quality of both audits and auditors and to more clearly define the acceptable EH&S audit—presently a nebulous concept. Given the varying types of audits and the multiple objec-tives a program can be designed to achieve, the development of standards will be a challenging exercise. Nonetheless, as shown in Figure 1.12, the U.S. EPA, the U.S. Department of Justice, the European Union, and the In-ternational Organization for Standardization (ISO) have developed standards and guidelines defining an acceptable environmental audit program.

■ The Use of Computers. Computers are now being used in a variety of ways

to support audit programs. They help to maintain online regulatory data-bases and audit protocols; they store audit reports, action plans, and facility schedules; and portables are increasingly used in the field to develop de-briefing documents and draft reports. In some cases, permit and other regu-latory information, such as training records, are being filed centrally on com-puters and accessed as part of the audit’s pre-visit activities.

■ An Emphasis on Management Audits. Through the EH&S audit, many

companies have found that inadequate attention to management systems has been central to the most significant compliance problems identified at oper-ating facilities. Two examples are in the areas of maintenance and emer-gency response. Lack of an adequate maintenance program can turn a “gold-plated” pollution control facility into a continuing compliance headache. The lack of a “working” emergency response system can turn a small spill or release into a major remediation project. Thus, many companies are now focusing their audit efforts on assuring that environmental management sys-tems are in place and functioning. The development of the ISO 14000 stan-dards has fostered this approach.

■ An Integration of Compliance Management Programs. Because of

1 U.S. EPA, “Environmental Auditing Policy Statement,” Final Policy Statement (July 9, 1986); and “Incentives for Self-Policing: Discovery, Disclosure, Correction and Prevention of Violations,” Final Policy Statement (January 22, 1996).

2 U.S. Sentencing Commission, “Draft Corporate Sentencing Guidelines for Environmental Violations” (November 16, 1993).

3 European Union Regulation 1836/93, Allowing Voluntary Participation in an Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS), O.J.L. 168/1 (July 10, 1993).

4 International Organization for Standardization (ISO), “Guidelines for Environmental Auditing, ISO 14010 (General Principles), 14011 (Audit Procedures) and 14012 (Qualification Criteria for Environmental Auditors)” (Fall 1996).

N O I T A T C E P X E A P