A THESIS

THE DEVELOPMENT OF SYNTAX OF CHILDREN AT 20-48 MONTHS

Submitted to the English Applied Linguistics Study Program as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Magister Humaniora

By:

WIDI DAMAIYANTI SIMBOLON

Registration Number: 8116112020

ENGLISH APPLIED LINGUISTICS STUDY PROGRAM

POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL

STATE UNIVERSITY OF MEDAN

ABSTRAK

Simbolon, Damaiyanti Widi. 2016. Perkembangan Sintaksis Anak Usia 20-48 bulan. Linguistik Terapan Bahasa Inggris, Universitas Negeri Medan.

ABSTRACT

Simbolon, Damaiyanti Widi. 2016. The Development of The Syntax of The Children 20-48 monhts. A Thesis English Applied Linguistics, Graduate Program of UNIMED

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, the writer would like to express her sincere gratitude to the Heavenly Father, Son of God Jesus Christ, and Holy Spirit for His amazing grace in the completion of this thesis to obtain a Master Degree in Applied Linguistics. This thesis process is filled with people who challenge, support, love, listen and frankly tolerate the writer. The process is a rewarding learning experience and the writer has learned enough about it. This thesis would not have been possible without the support and input of numerous people to whom the writer expresses her deeply gratitude.

The writer would like to express the greatest thanks to Prof. Dr. Berlin Sibarani, M.Pd and Siti Aisyah Ginting, M.Pd, as her advisers for their great ideas, guidance and patience that lead the writer to the end of completion of this thesis.

The writer also would like to extend her sincere gratitude to the Head of English Applied Linguistics Study Program, Dr. Rahmad Husein, M.Ed, the secretary of English Applied Linguistics Program, Prof. Dr. Sri Minda Murni, M.S and Farid Ma’ruf as an administrator for their assistance regarding the administrative procedures and support during the writer’s thesis completion process patiently.

In addition, the writer would like to thank to all lecturers for their knowledge and character building during the process of teaching and learning.

Then, the writer’s great respect and heartfelt thanks go to all her lovely friends in the executive class B LTBI XX as well

Last and most importantly, the writer wishes to express her sincere thanks to her beloved parents, Mr. M. Simbolon and Ms. Nurmada br Sinaga for their continued and unfailing love, patience, guidance, prayer and support over years and their endless faith in the writer’s ability to accomplish this thesis. Her huge thanks are also dedicated to her great sister, Deasy Simbolon, S.E,her love, assistance, and support. “Family has been an integral part of this process”.

Finally, the writer’s special love goes to her loving husband, Poltak , S.T who made an arduous task a more enjoyable and fulfilling experience. Her husband’s love, support, patience and encouragement have seen her through uncertain times. For that, the writer can only say ‘thanks my soul mate’.

Medan, 5 April 2016

2.2 The Acquisition of Syntax………. 14

2.3 The Nature of Language Acquisition……… 16

2.3.1 Language Acquisition……… 19

2.3.1.1 Empiricism………. 21

2.3.1.2 Nativism………. 26

2.4 The Development of Acquisition………. 32

2.4.1 Pre-Language Stages……… 34

2.4.2 The One-Word or Holophrastic Stage………. 35

2.4.2 The One-Word or Holophrastic Stage………. 35

2.4.3 The Two-Word Stage……….. 36

2.4.4 The Telegraphic Speech……….. 37

2.5 Factors Affecting Acquisition………. 40

2.5.1 Input………. 40

3.3 Technique of Collecting the Data……… 51

3.4 Technique of Analyzing Data……… 52

3.5 Trustworthiness of The Study……… 54

CHAPTER IV DATA ANALYSIS, FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION 4.1 Data Analysis………. 56

4.1.1 The Syntactic Category Acquired by Children of 20-48 Months Old………. 56

4.1.1.1 The Syntactic Category for Phrase Acquired by The Children……….. 56

4.1.2 The Development of The Syntax of The Children with 20-48 months Old………. 65

4.1.2.1 The Development of Phrases Acquisition……….. 65

4.1.2.2 The Development of Sentence Acquisition………... 69

4.2 Findings……….…… 71

CHAPTER V CONCLUSSION AND SUGGESTION

5.1 Conclusions……….……….. 76

5.2 Suggestions……… 77

References……….. 78

List of Figure

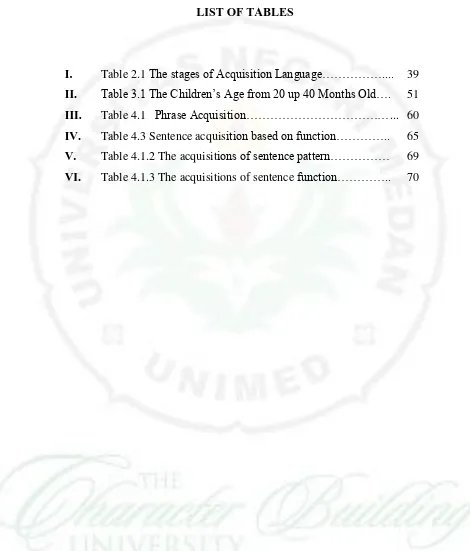

LIST OF TABLES

I. Table 2.1 The stages of Acquisition Language……….... 39

II. Table 3.1 The Children’s Age from 20 up 40 Months Old…. 51

List of Lists

List I……… 66

List II……….. 66

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.1The Background of the Study

The acquisition of a first language is a complex topic that requires an

interdisciplinary approach. It has been traditionally studied within the field of

psycholinguistics, but contributions from other disciplines such as biology,

education or the social sciences are necessary to gain a wider perspective.

Language acquisition serves as one of the central topics in cognitive

science. Every theory of cognition has tried to explain it; probably no other topic

has aroused such controversy. Possessing a language is the quintessence of human

trait: all normal human speak, no nonhuman animal does. Language is arguably

the most important components of culture because much of the rest of it is

normally transmitted orally. It is impossible to understand the subtle nuances and

deep meanings of another culture without speaking its language. Language then is

the main vehicle by which we know about other people‟s thoughts, and the two

must be intimately related.

Every time we speak we are revealing something about language. So the

facts of language structure are easy to come by; these data hint at a system of

extraordinary complexity. Nonetheless, learning a first language is something

every normal child does successfully, in a matter of a few years and without the

need for formal lessons. With language so close to the core of what it means to

so much attention. Anyone with strong views about the human mind would like to

show that children‟s first few steps are steps in the right direction.

When children develop such skill is always a difficult question to answer.

Acquiring a language is a skill that children begin to develop with the first sounds

they make as babies. For most children, their first words are made up of simple

sounds such Mama, Dada or Bye-bye. As early as the first and second years,

children‟s speech exhibits a variety of complex ideas (Clark, 2003). For example,

children say such things as „big truck‟ (semantically, the object „truck‟ is assigned

the attribute „big‟) „Daddy chair‟ (the object „Daddy‟ possesses another object

„chair‟), and „Mommy give‟ ( the object „Mommy‟ is the cause of an action of

„giving‟). Next they begin to use complex sentences, to produce longer words that

require more fine motor control by the age of 4 to 4 ½ years. Gradually children

begin to use their speech skills, or sounds, to form language that refers to the use

of words and sentences to convey ideas. By the time they start kindergarten,

children know most of the fundamental of their language. They have speech that

is easily understood by an unfamiliar listener so that they are able to converse

easily with someone who speaks as they do (that is, in their dialect). This

development of oral language is one of children‟s most natural and impressive

accomplishments and as with others aspects of development, language acquisition

is not predictable. One child may say her first word at 10 months, another at 20

months. One child may use complex sentences at 5 ½ years, another at 3 years.

Since language itself does not provide the child with such ideas as object,

acquired them. Obviously, interaction with the world is necessary. But, were the

basic ideas already in the mind in some form even before

The physical stimuli of the world were sensed, i.e. the innate ideas view of

the relation lists? Or, were the ideas derived entirely through experience with

none being in the mind (latent or otherwise) prior to experiencing of the world,

i.e. the experiential view of the Empiricists? As far as language acquisition data

are concerned, presumably none will serve to settle any of these controversies.

Both the Rationalist and Empiricist theories are sufficiently vague so that any

observational datum can be given an explanation. Aside from such ultimate, there

still a great deal that can be discovered about how human beings acquire

language.

The rules of their language are learned at an early age through use, and

over time, without formal instruction. Thus one source for learning must be

genetic. Human beings are born to speak; they have an innate gift for figuring out

the rules of the language used in their environment. The environment itself is also

a significant factor. Children learn the specific variety of language (dialect) that

the important people around them speak.

It is acknowledged that children work through linguistic rules on their own

not merely through imitating those around them because young children tend to

use forms that adults never use, such examples are best seen through the sentences

uttered by English- speaking children like “ I goed there before” or “I see your

feets” (Genishi, 1988:16-23). These problems of grammar first appear when

assumed that children do not start to work on inflectional morphology or on

grammatical morphemes more generally until after they have begun to combine

two or more words (Brown, 1973 in Clark, 2003: 191). Being capable of

producing such utterances, children, in English and many other languages, set out

to alter single words in order to indicate number (the –s ending in English) and

tense (-ed in English), or other inflections of meaning. Just as in word learning,

children frequently make errors of overgeneralization. For instance when-

speaking children learn that the –ed ending indicates past tense, they tend to use it

for all verbs, including those that are irregular and do not take the –ed ending in

adult speech (such as “go” or “think”). This is excellent evidence that children are

learning the systems of their language: they are producing words according to the

basic rules of the language, rather than by simple imitation of the language they

hear. Only after extensive practice with both the rule and its exceptions does the

child learn to speak as an adult. Children eventually learn the conventional past

tense forms for irregular verbs and irregular plural forms like, “went” and “feet”,

as they sort out for themselves the exceptions to the rules of English syntax. As

with learning to walk, learning o talk requires time for development and practice

in everyday situations. Constant correction of a child‟s speech is usually

unproductive.

Moreover, children seem to be born not just to speak, but also to interact

socially. Even before they use words, they use cries and gestures to convey

meaning; they often understand the meanings that others convey. The point of

connections with other people and to make sense of experiences for language

occur through an interaction among genes (which hold innate tendencies to

communicate and be sociable), environment, and the child‟s own thinking

abilities.

Given the above views on language acquisition, each must account for

some facts about child language development. First, children learn language

rapidly. In only a few years, children progress from virtually no language

comprehension or production to almost adult capacity. Second, across language,

some systematic regularities exist in what children learn both early and late. As

well as some differences that require explanation.

Sometime during their second year, after children have about 50 of these early

words of English in their vocabularies, they begin to put those words together

into rudimentary two-word sentences (Brown, 1973 in Gleason and Ratner,

1993;366). Words that they said in the one-word stage are now combined into

short utterances. In English such utterances lack articles, prepositions, inflections,

or any of the other grammatical modifications that well-formed adult language

requires.

An examination of children‟s two-word utterances in many different

language communities has suggested that everywhere in the world children at this

age are expressing the same kinds of thoughts and intentions in the same kinds of

utterances (Brown, 1973 in Gleason and Ratner, 1993:366). At this stage, children

acquiring English express basic meanings, but they lack the grammatical forms of

in meaning and are produced without function words or inflections. In spite of

that, these two-word utterances do include some kind of grammatical information.

The phrase „ hit Andy” means something different to a child that “Andy hit”.

Children appear to be able to produce this kind of difference as soon as they begin

to produce multi-word utterances, and they comprehend it even earlier. This

brings up an important point in language acquisition and other parts of

developmental psychology: an inability to produce a certain behavior does not

mean that the corresponding cognitive structures are absent. Children are able to

understand grammatically complex sentences and words long before they are able

to produce them.

It must be noted too that language acquisition is marked by individual

variation as well as generalized developmental trends. Thus, some children seem

to appreciate the adult language patterns before being able to produce aspects of

the grammar; such children may use adult- like prosody and “dummy syllables” to

fill in between those vocabulary items they are capable of producing, saying, [wan

a kuki] for “ I want the cookie‟. Children with a more analytic style appear

comfortable producing “ Want cookie”, until they can incorporate the additional

grammatical elements into their output. Similarly, even when children use only

single words to communicate, stylistic variation in the kinds of words most

frequently used by children can be seen. Some children appear to build their initial

lexicons by incorporating many names for objects; other children may include

proportionately more verb or “social” items such as hi, bye, please, and so forth

Most people acquire their own language without fully realizing how it is

taking place. Young children need to use language to make sense of the world

they live in. they gradually learn to understand and use rules of the language

spoken in their society. Their language-using abilities are formed by the

unification of the maturity of the infants‟ rain which is tied very much to their

biological and cognitive development and interplay with many social factors in

their environment.

In general, all normal children, regardless of their culture, develop

language at the roughly the same time along with the same schedules of the

biological and cognitive development. It has been already noted that a child who

does not hear, or is no allowed to use language, will learn no language. The child

must be physically capable of sending and receiving sound signals in a language.

In order to speak a language, a child must be able to hear the language being used.

There are two views which explain how children manage to acquire the

adult language. First, they are empiricists, who propose that language is learned as

a result of experience. This view then is observed through its two theories, the

„imitation‟ and „reinforcement‟ theory. The first thinks that children merely

imitate what they hear. And the second suggests that a child learns to produce the

correct words or sentences because he is positively reinforced when he says

something right and negatively reinforced when he says something wrong. The

other view comes from nativists who propose that language acquisition is the

Before he produces those spoken words, a child in his life utters very

limited and simple utterances based on the things he sees, feels, and hears which

are usually relied on all the kinds of nonlinguistic-cue-direction of gaze, gestures,

and the context itself. He firstly starts producing babbling sounds which have no

linguistic significance. Then sometimes after one year the child begins to use

single unit utterances to mean everyday objects he sees. As the child has been able

to put two words together to form one sentence, he now starts producing multiple

word utterances.

Based on the description above, the writer found some interesting things in

this study. The appearance of baby‟s first words can be said to depend on some

factors such as culture, social environment, family background, etc. the baby

usually needs a stimulus in order to give a response, just like what behaviorists

believes. Thus it is very possible that the development of language of a child is

different from one another. A child may be able to produce words in earlier age

than another. Based on the writer‟s view children at the same age have significant

differences of development in acquiring syntax. Secondly, the writer is interested

in studying what kinds of syntax that a child of twenty until forty eight months

acquired.

Because this research is a case study of a child of 20-48 months therefore,

1.2 The Research Problems

The main problems that will be discussed in this research are:

1. What syntactic category do the children acquire from the age of 20up 48

months old?

2. How is the development of the syntax of the children with 20-48 months old?

1.3The Objectives of the Study

This study is devoted to analyze the development of syntactical acquisition

of 20- 48 months child and to identify and describe the syntax words the subject

acquired at the age 20-48 months.

1.4The Scope of the Study

This study is limited only on the development of a 20-48 months child‟s

syntactical acquisition in Indonesian Language that he acquires in speaking

ability.

1.5The Significance of the Study

It is expected that the findings of this study will be significantly relevant to

the theoretical and practical aspects. Theoretically, the research findings hopefully

can provide significant contribution for a further research on language acquisition

in Indonesian Language of different stages. Practically, on the other hand, this

research hopefully can provide valuable information for parents who are

REFERENCES

Atkinson, J.M. & David , K.& Iggy, R. 1982. Foundation of General Linguistics. London: George & Unwin.

Bickerton, D. (2001) The language bioprogram hypothesis. Behavioral and Brain

Sciences, 7, 173-221.

Bloom, L. (1970). Language Development: Form and Function in Emerging

grammars. Cambridge.

Bloom, L.M. 1972. Language Development. Cambridge.

Bloor, T. and Bloor, M. 1995. The Functional Analysis of English: A Hallidayan

Approach. London: Arnold.

Bolinger, Dwight. And A. Sears, Donald. 1981. Aspects of Language. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Brandone, C. Amanda. (2002). Language Development. University of Delaware. Brown, R., & Hanlon, C. (1970). Derivational complexity and order of

acquisition in child speech. In J. R. Hayes (Ed.), Cognition and the

Development of Language. New York: Wiley.

Brown, R. (1973). The Development of Language. New York: Longman.

Brown, R. (1977) 'Introduction' in C. Snow and C. ferguson (eds.).Talking to

Children: Language input and acquisition. New York: Longman.

Brown, H.D. 1987. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. New Jersey: University Of Jersey.

Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching. New York: Longman.

Cattell, R. (2000). Children’s Language. London:Cassell.

Chomsky, N. 1959. A Review of B.F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior. Language; in Smolinski, Frank (ED), Landmark of American Language and Linguistics, 35 (1): 26-58. Washington, D.C.USIA.

Clark, E.V. 2003. First Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cooper, Robin, Aslin, Richard N. (1989). The Language Environment of the

Young Infant:Implications for Early Perceptual Development. Special

Issue: Infant. Smith, Domenico Parisi, and Kim Plunkett. 1999. Rethinking innateness:

A connectionist perspective ondevelopment. Cambridge.

Ellidokuzoglu, H. 1999. The Role of Innate Knowledge in Second Language

Acquisition. Science Journal of Army Academy, 1 (1): 13-30.

Ferguson, C. A. & Snow, C. E. (Eds). (1977). Talking to children. Language input

and acquisition. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press.

Fernald, Anne, Kuhl, Patricia K. (1987). Acoustic Determinants of Infant

Preference for Motherese Speech. Infant Behavior and Development. (3)

279-293.

Fodor, J. A. 1983. The Modularity of Mind. Cambridge: The MIT Pres. Fon, Jenice. 2001. Syntax. Ohio State University.

Foss, J. Donald and T. David, Hakes. 1978. Psycholinguistics: And Introduction

to the Psychology of Language. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Gelderen, Elly Van. 2002.An Introduction to the Grammar of

English.Amsterdam: Arizona State University.

Genishi. C.1988.Young Children’s Oral Language Development. Young Children, 1 (44): 16- 23.

George, 1980. Let’s Write English. New York. United State of America.

Gleason, Jean Berko and Ratner, Nan Berneisten. 1993. Language Acquisition; in Gleason,Jean Berko and Ratner, Nan Berneisten (Eds.), Psycholinguistcs (Pp. 364-375).

Gold, E. (1967). Language identification in the limit. Information and Control, 10, 447-474

Greenbaum, 2002, An Introduction to English Grammar, Edinburg, Pearson Educational Limited.

Hepper, Peter G, Scott,D., Shahidullah, Sara. (1993). Newborn and Fetal Response to Maternal Voice. Special Issue:Prenatal and Paranatal

Behavior. Journal of reproductive & infant Phsychology. (11). 147-153.

Hirsh-Pasek, K., Treiman, R., & Schneiderman, M. (1984). Brown and Hanlon revisited: Mothers' sensitivity to ungrammatical forms. Journal of Child `Language, 11, 81-88.

Hong, Z. F. & Li, S. L. (2004). The impact of foreign spouses’ teaching attitude

on children’s verbal expression. Thesis of the development of children

education. National Hua-lien Teaching College.

Ingram, David. 1974. Phonological rules in young children. Journal of Child

Language 1. 49-64.

Ingram, David. 1989. First Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Ingram, D.(1991). First Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University .

Kess, J. F. (1993). Psycholinguistics. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. Krashen, S. 1972. Language and the Lefts Hemisphere. UCLA Work Pap.

Phonetics, 24.

Kuhl, L. Patricia. Early Language Acquisition. University of Washington.

Labov, W. (1969) The logic of nonstandard English. Georgetown Monographs on Language and Linguistics, 22, 1-31.

Marcus, G. F. (1993) Negative evidence in language acquisition. Cognition, 46], 53-85.

Miles, M.B. & Huberman, A.M. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis.London.Sage. Newport, E., Gleitman, H. & Gleitman, E. (1977) Mother I'd rather do it myself:

Some effects and non-effects of maternal speech style. In C. E. Snow and

Olson, S. L. (1986). Mother-child interaction and children's speech progress: A longitudinal study of the first two years. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 32(1), 1-20.

Painter, Claire. 1984. Into the mother tongue: A case study in Early Language

Development. London: Frances Pinter.

Penner, S. (1987) Parental responses to grammatical and ungrammatical child

utterances. Child Development 58: 376-384.

Pinker, S. (1979) Formal models of language learning. Cognition, 7, 217-283. Pinker, S. (1989) Learnability and cognition: The acquisition of argument

structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pinker, S. (1994a) The language instinct. New York: Morrow.

Skinner, B.F. (1957). Verbal Behavior.NY: Appleton. [Spanish translation: Conducta Verbal. Mexico, Trillas (1957).].

Slobin, D.I. 1994.The Human Language Series 2. Colombia: Colombia University.

Sutherland, Stuart. 1989. Macmillan Dictionary of Psychology. London: Macmillan.

Tarigan, Guntur Henry. 1986. Psikolinguistik. Bandung: Angkasa Bandung. Tarigan, Guntur Henry. 1988. Psikolinguistik. Bandung: Angkasa Bandung. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological

processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Whitehurs, G. (1982). Language development. In B. Wolman (Ed), Handbook of

development psychologty. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.