Forensic Science International is an international journal publishing original contributions in the many different scientifi c disciplines pertaining to the forensic sciences. Fields include forensic pathology and histochemistry, chemistry, biochemistry and toxicology (including drugs, alcohol, etc.), biology (including the identifi cation of hairs and fi bres), serology, odontology, psychiatry, anthropology, the physical sciences, fi rearms, and document examination, as well as investigations of value to public health in its broadest sense, and the important marginal area where science and medicine interact with the law. Review Articles and Preliminary Communications (where brief accounts of important new work may be announced with less delay than is inevitable with major papers) may be accepted after correspondence with the appropriate Editor. Case Reports will be accepted only if they contain some important new information for the readers.

Submission of Articles: Manuscripts prepared in accordance with Instructions to Authors should be sent to the Editor-in-Chief or one of the Associate Editors

according to their area of expertise as listed below. If there is any doubt, a preliminary letter, telefax or telephone enquiry should be made to the Editor-in-Chief or his Assistant.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

P. Saukko – (for: Experimental Forensic Pathology, Traffi c

Medicine and subjects not listed elsewhere) Department of Forensic Medicine, University of Turku, SF-20520 Turku, Finland Tel.: (+358) 2 3337543; Fax: (+358) 2 3337600; E-mail: psaukko@utu.fi

A. Carracedo – (for: Forensic Genetics)

Instituto de Medicina Legal, Facultad de Medicina,

15705 Santiago de Compostela, Galicia, Spain Fax: (+34) 981 580336

Cristina Cattaneo – (for: Anthropology and Osteology)

Instituto de Medicina Legal, Universit`a degli Studi Via Mangiagalli 37, 20133 Milano, Italy

Tel: 0039 2 5031 5678; Fax: 0039 2 5031 5724

O.H. Drummer – (for: Toxicology)

Department of Forensic Medicine, Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine

57–83 Kavanagh Street, Southbank 3006, Victoria, Australia Tel.: (+61)-3-9684-4334;

Fax: (+61)-3-9682-7353

Assistant Editor: M.A. LeBeau (Quantico, VA, USA)

Tel: (+1) 703 632 7408; [email protected]

C. Jackowski (for: Forensic Imaging)

Institut für Rechtsmedizin Medizinische Fakultät Universität Bern Bühlstrasse 20 3012 Bern, Switzerland Tel.: +41 (0)31 631 8411 Fax : +41 (0)31 631 38 33

P. Margot – (for: Questioned Documents, with the assistance of A. Khanmy and

W. Mazzela; and for Physical Science: ballistics, tool marks, contact traces, drugs analysis, fi ngerprints and identifi cation, etc.)

Ecole de Sciences Criminelles (ESC), UNIL-BCH, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland Fax: (+41) 21 692 4605

Assistant Editor: P. Esseiva (Lausanne, Switzerland)

Tel: (+41) 21 692 4652; [email protected]

Martin Hall – (for: Forensic Entomology)

Department of Life Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK

Tel: 0044 207 942 5715 Fax: 0044 207 942 5229

G. Willems – (for: Odontology)

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, School of Dentistry, Oral Pathology and Maxillo-Facial Surgery, Departments of Orthodontics and Forensic Odontology, Kapucijnenvoer 7, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium

Tel: +32 16 33.24.59; Fax: +32 16 33.24.35 ASSOCIATE EDITORS

J. Amendt (Frankfurt, Germany) P. Beh (Hong Kong, China) P. Buzzini (Morgantown, WV, USA) H. Chung (Seoul, Korea)

J. Clement (Melbourne, Australia) S.D. Cohle (Grand Rapids, MI, USA) S. Cordner (South Melbourne, Australia) P. Dickens (Buxton, UK)

H. Druid (Stockholm, Sweden) A. Eriksson (Umeå, Sweden) J.A.J. Ferris (Auckland, New Zealand) M.C. Fishbein (Encino, USA)

G. L. de la Grandmaison (Garches, France) C. Henssge (Essen, Germany)

M.A. Huestis (Baltimore, MD, USA) A.W. Jones (Linköping, Sweden)

H. Kalimo (Helsinki, Finland) Y. Katsumata (Kashiwa, Japan) B. Kneubuehl (Thun, Switzerland) G. Lau (Singapore)

S. Leadbeatter (Cardiff, UK) C. Lennard (Canberra, Australia)

A. Luna Maldonado (Espinardo (Murcia), Spain) B. Madea (Bonn, Germany)

H. Maeda (Osaka, Japan)

D. Meuwly (The Hague, The Netherlands) C. Neumann (Pennsylvania, USA) S. Pollak (Freiburg i. Br., Germany) M.S. Pollanen (Toronto, Canada) D. Pounder (Dundee, UK) K. Püschel (Hamburg, Germany) G. Quatrehomme (Nice, France)

R. Ramotowski (Washington, DC, USA) J. Robertson (Canberra, Australia) C. Roux (Sydney, Australia) I. Sääksjärvi, (Turku, Finland) J. Stevens (Exeter, UK) M. Steyn (Pretoria, South Africa) F. Tagliaro (Verona, Italy) T. Takatori (Chiba, Japan) A. Thierauf (Freiburg, Germany) D. Ubelaker (Washington D.C., USA) D.N. Vieira (Coimbra, Portugal) J. Wells (Miami, FL, USA) P. Wiltshire (London, UK)

X. Xu (Shantou, People’s Republic of China) J. Zieba-Palus (Krakow, Poland)

CHAIRMAN FORENSIC SCIENCE INTERNATIONAL: P. Saukko (Turku, Finland)

Content

Profiles of pregabalin and gabapentin abuse by

postmortem toxicology

Margareeta Häkkinen, Erkki Vuori, Eija Kalso, Merja Gergov, Ilkka

Ojanperä

p1

–

6

Published online: May 3, 2014

Demonstration of spread-on peel-off consumer

products for sampling surfaces contaminated with

pesticides and chemical warfare agent signatures

Deborah L. Behringer, Deborah L. Smith, Vanessa R. Katona, Alan T. Lewis

Jr., Laura A. Hernon-Kenny, Michael D. Crenshaw

p7

–

14

Published online: May 5, 2014

Elderly arrestees in police custody cells:

implementation of detention and medical decision

on fitness to be detained

Aurélie Beaufrère, Otmane Belmenouar, Patrick Chariot

p15

–

19

Published online: May 5, 2014

Instar determination in forensically useful

beetles

Necrodes littoralis

(Silphidae)

and

Creophilus maxillosus

(Staphylinidae)

Katarzy a Frąt zak, Szy o Matuszewski

p20

–

26

Published online: May 2, 2014

Evaluation of a homogenous enzyme immunoassay

for the detection of synthetic cannabinoids in urine

Allan J. Barnes, Sheena Young, Eliani Spinelli, Thomas M. Martin, Kevin L.

Klette, Marilyn A. Huestis

p27

–

34

Terrestrial laser scanning and a degenerated

cylinder model to determine gross morphological

change of cadavers under conditions of natural

decomposition

Xiao Zhang, Craig L. Glennie, Sibyl R. Bucheli, Natalie K. Lindgren, Aaron

M. Lynne

p35

–

45

Published online: May 13, 2014

Assessment and forensic application of

laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) for the

discrimination of Australian window glass

Moteaa M. El-Deftar, Naomi Speers, Stephen Eggins, Simon Foster, James

Robertson, Chris Lennard

p46

–

54

Published online: May 7, 2014

Analysis of chain saw lubricating oils commonly

used i Thaila d s southe o de p ovi es fo

forensic science purpose

Aree Choodum, Kijja Tripuwanard, Niamh Nic Daeid

p60

–

68

Published online: May 3, 2014

Identification of scanner models by comparison of

scanned hologram images

Shigeru Sugawara

p69

–

83

Published online: April 30, 2014

Cross-reaction of propyl and butyl alcohol

glucuronides with an ethyl glucuronide enzyme

immunoassay

Torsten Arndt, Reinhild Beyreiß, Stefanie Schröfel, Karsten Stemmerich

p84

–

86

Morphine and codeine concentrations in human

urine following controlled poppy seeds

administration of known opiate content

Michael L. Smith, Daniel C. Nichols, Paula Underwood, Zachary Fuller,

Matthew A. Moser, Charles LoDico, David A. Gorelick, Matthew N.

Newmeyer, Marta Concheiro, Marilyn A. Huestis

p87

–

90

Published online: May 12, 2014

Evaluating the utility of hexapod species for

calculating a confidence interval about a succession

based postmortem interval estimate

Anne E. Perez, Neal H. Haskell, Jeffrey D. Wells

p91

–

95

Published online: May 19, 2014

Development of a GC

–

MS method for

methamphetamine detection in

Calliphora

vomitoria

L. (Diptera: Calliphoridae)

Paola A. Magni, Tommaso Pacini, Marco Pazzi, Marco Vincenti, Ian R.

Dadour

p96

–

101

Published online: May 19, 2014

Effects of methamphetamine and its primary

human metabolite,

p-

hydroxymethamphetamine,

on the development of the Australian

blowfly

Calliphora stygia

Christina Mullany, Paul A. Keller, Ari S. Nugraha, James F. Wallman

p102

–

111

Published online: May 19, 2014

Postmortem volumetric CT data analysis of

pulmonary air/gas content with regard to the cause

of death for investigating terminal respiratory

function in forensic autopsy

Nozomi Sogawa, Tomomi Michiue, Takaki Ishikawa, Osamu Kawamoto,

Shigeki Oritani, Hitoshi Maeda

Published online: May 24, 2014

Age estimation in U-20 football players using 3.0

tesla MRI of the clavicle

Volker Vieth, Ronald Schulz, Paul Brinkmeier, Jiri Dvorak, Andreas

Schmeling

p118

–

122

Published online: May 20, 2014

Spine injury following a low-energy trauma in

ankylosing spondylitis: A study of two cases

Frederic Savall, Fatima-Zohra Mokrane, Fabrice Dedouit, Caroline

Capuani, Céline Guilbeau-Frugier, Daniel Rougé, Norbert Telmon

p123

–

126

Published online: May 28, 2014

The transferability of diatoms to clothing and the

methods appropriate for their collection and

analysis in forensic geoscience

Kirstie R. Scott, Ruth M. Morgan, Vivienne J. Jones, Nigel G. Cameron

p127

–

137

Published online: May 23, 2014

Lethal hepatocellular necrosis associated with

herbal polypharmacy in a patient with chronic

hepatitis B infection

John D. Gilbert, Ian F. Musgrave, Claire Hoban, Roger W. Byard

p138

–

140

Published online: June 2, 2014

Effect of massing on larval growth rate

Aidan P. Johnson, James F. Wallman

p141

–

149

Published online: May 17, 2014

Norcocaine in human hair as a biomarker of heavy

cocaine use in a high risk population

S. Poon, J. Gareri, P. Walasek, G. Koren

Published in issue: August 2014

Intuitive presentation of clinical forensic data using

anonymous and person-specific 3D reference

manikins

Martin Urschler, Johannes Höller, Alexander Bornik, Tobias Paul, Michael

Giretzlehner, Horst Bischof, Kathrin Yen, Eva Scheurer

p155

–

166

Published online: May 29, 2014

Factors leading to the degradation/loss of insulin in

postmortem blood samples

Cora Wunder, Gerold F. Kauert, Stefan W. Toennes

p173

–

177

Published online: June 11, 2014

Utility of urinary ethyl glucuronide analysis in

post-mortem toxicology when investigating

alcohol-related deaths

M. Sundström, A.W. Jones, I. Ojanperä

p178

–

182

Published online: June 2, 2014

DNA evidence: Current perspective and future

challenges in India

Sunil K. Verma, Gajendra K. Goswami

p183

–

189

Published online: May 30, 2014

An RNA-based analysis of changes in biodiversity

indices in response to

Sus scrofa

domesticus

decomposition

R.C. Bergmann, T.K. Ralebitso-Senior, T.J.U. Thompson

p190

–

194

Epifluorescence analysis of hacksaw marks on bone:

Highlighting unique individual characteristics

Caroline Capuani, Céline Guilbeau-Frugier, Marie Bernadette Delisle,

Daniel Rougé, Norbert Telmon

p195

–

202

Published online: June 7, 2014

Prevalence of medicinal drugs in suspected

impaired drivers and a comparison with the use in

the general Dutch population

Karlijn D.B. Bezemer, Beitske E. Smink, Rianne van Maanen, Miranda

Verschraagen, Johan J. de Gier

p203

–

211

Published online: June 12, 2014

Sampling of illicit drugs for quantitative analysis

–

Part III: Sampling plans and sample preparations

T. Csesztregi, M. Bovens, L. Dujourdy, A. Franc, J. Nagy

p212

–

219

Published online: April 28, 2014

Detection of recent holding of firearms: Improving

the sensitivity of the PDT test

Joseph Almog, Karni L. Bar-Or, Amihud Leifer, Yair Delbar, Yinon

Harush-Brosh

p55

–

59

Published online: May 7, 2014

Morphological variations of the anterior thoracic

skeleton and their forensic significance:

Radiographic findings in a Spanish autopsy sample

P. James Macaluso Jr., Joaquín Lucena

p220.e1

–

220.e7

Published online: May 20, 2014

Forensic aspect of cremations on wooden pyre

Veronique Alunni, Gilles Grevin, Luc Buchet, Gérald Quatrehomme

p167

–

172

A body, a dog, and a fistful of scats

Ignasi Galtés, María Ángeles Gallego, Dolors Giménez, Verònica Padilla,

Mercè Subirana, Carles Martín-Fumadó, Jordi Medallo

e1

–

e4

Published online: April 16, 2014

Quantitative analysis of quazepam and its

metabolites in human blood, urine, and bile by

liquid chromatography

–

tandem mass spectrometry

Jing Zhou, Koji Yamaguchi, Youkichi Ohno

e5

–

e12

Published online: May 3, 2014

The identification of an impurity product,

4,6-dimethyl-3,5-diphenylpyridin-2-one in an

amphetamine importation seizure, a potential

route specific by-product for amphetamine

synthesized by the APAAN to P2P, Leuckart route

Joh D. Power, Joh O’Brie , Bria Tal ot, Mi hael Barry, Pier e

Kavanagh

e13

–

e19

Published online: May 5, 2014

Further occurrences of

Dohrniphora cornuta

(Bigot)

(Diptera, Phoridae) in forensic cases indicate likely

importance of this species in future cases

R. Henry L. Disney, Ana Garcia-Rojo, Anders Lindström, John D. Manlove

e20

–

e22

Published online: May 23, 2014

Unintentional lethal overdose with metildigoxin in

a 36-week-old infant

–

post mortem tissue

distribution of metildigoxin and its metabolites by

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

Cornelius Hess, Christopher Brockmann, Elke Doberentz, Burkhard

Madea, Frank Musshoff

e23

–

e27

Post-

o te β

-hydroxybutyrate determination in

synovial fluid

Cristian Palmiere, Dominique Werner

e28

–

e30

Published online: May 2, 2014

E atu to sa pli g of illi it d ugs fo ua titative

analysis

–

Part II. Study of particle size and its

i flue e o ass edu tio (Fo e si S ie e

International 234C (2014) 174

–

180)

M. Bovens, T. Csesztregi, A. Franc, J. Nagy, L. Dujourdy

p221

Published online: June 11, 2014

Inside Front Cover- Editorial Board

IFC

Effects

of

methamphetamine

and

its

primary

human

metabolite,

p-

hydroxymethamphetamine,

on

the

development

of

the

Australian

blow

fl

y

Calliphora

stygia

Christina

Mullany

a,

Paul

A.

Keller

b,

Ari

S.

Nugraha

b,

James

F.

Wallman

a,*

aInstituteforConservationBiologyandEnvironmentalManagement,SchoolofBiologicalSciences,UniversityofWollongong,NSW2522,Australia bSchoolofChemistry,UniversityofWollongong,NSW2522,Australia

ARTICLE INFO

Articlehistory:

Received22April2013

Receivedinrevisedform6April2014

Accepted8May2014

Availableonline20May2014

Keywords:

Forensicentomology

Entomotoxicology Calliphorastygia

Insectdevelopment

Methamphetamine

Postmorteminterval

ABSTRACT

Thelarvaeofnecrophagousflyspeciesareusedasforensictoolsforthedeterminationoftheminimum postmorteminterval(PMI).However,anyingesteddrugsincorpsesmayaffectlarvaldevelopment,thus leading to incorrect estimates of the periodof infestation. This study investigated the effects of methamphetamine and itsmetabolite, p-hydroxymethamphetamine, on theforensically important AustralianblowflyCalliphorastygia.Itwasfoundthatthepresenceofthedrugssignificantlyaccelerated larvalgrowthandincreasedthesizeofalllifestages.Furthermore,drug-exposedsamplesremainedas pupaeforupto78hlongerthancontrols.ThesefindingssuggestthatestimatesoftheminimumPMIof methamphetamine-dosedcorpsescouldbeincorrectifthealteredgrowthofC.stygiaisnotconsidered. Differenttemperatures,drugconcentrationsandsubstratetypesarealsolikelytoaffectthedevelopment ofthisblowfly.Pendingfurtherresearch,theapplicationofC.stygiatotheentomologicalanalysisof methamphetamine-relatedfatalitiesshouldbeappropriatelyqualified.

ã2014ElsevierIrelandLtd.Allrightsreserved.

1.Introduction

Analysis of entomologicalevidence can greatlyenhance the scopeofdeathinvestigationswheresuchevidenceispresent[1].A primaryobjectiveofforensicexaminationsuponfindingacorpseis thedetermination of theminimumpostmortem interval (PMI). Thisisoftenmadebystudyinganyinfestinginsects[2],especially

flies (Diptera),and involves an understandingof the biological characteristicsofthespecies present incarrion,including their development[3]. By determiningtheage ofthese insects, it is possibletodeterminetheirtime ofcolonisation,and hence,the minimum PMI [2]. Although the developmental rates of many forensically important species are known [4,5], bioclimatic influenceshavebeenshowntoaffectgrowthratesofflyspecies

[6,7].These factorsincludetemperature,atmospheric humidity, larvaldensityandbodylocation.Anotableenvironmentaleffectof forensicimportanceisthepresenceofdrugsinacorpseandtheir subsequenteffectsoninsectphysiology.Thisisknownasforensic entomotoxicologyandfailuretoconsidersuchfactorsmayleadto errorsinminimumPMIestimates[8–10].Preliminarystudieshave

shownthatillicitdrugsinfluencethedevelopmentofvariousfly species [11–15]. In particular, the larvae of some species have shownaccelerated growthupon exposuretostimulants[12,16]. However, few investigations have been undertaken into the physiologicaleffectsofdrugsofabuseonAustralianflies.Ifthese endemicspeciesaretobesuccessfullyusedtocorrectlyestimate minimum PMI, it is imperative to understand the effect of antemortem drug use and abuse on the growth rate in the postmortemperiod[17].

Theworldwideabundanceandsocialpopularityof metham-phetamine make it a prime candidate for entomotoxicological analysis.Thepotentialforaddictionoroverdoseforfirst-timeusers isoneofthehighestofallavailabledrugsduetoitsextremeand enduringphysiologicaleffects[18–20].Inpreviousexperiments, wholeanimalshavebeenusedtosimulatethepharmacokineticsof methamphetamineinhumans[12,20–22],however,thereisstill somedebateastowhetherthisisoptimalasithasbeenreported that drugmetabolism is species-specific[23]. Furthermore,the metabolicbreakdownandexcretion ratesof methamphetamine are also species-dependent. When compared to laboratory rodents,methamphetamineismetabolised ataslower rateand lesseffectivelyinhumans[23].Asaresult,sustained administra-tion of drugs is required to achieve plasma, urine or tissue concentrations comparable to humans, which in turn produce

*Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+61242214911;fax:+61242214135.

E-mailaddress:[email protected](J.F. Wallman).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.05.003

0379-0738/ã2014ElsevierIrelandLtd.Allrightsreserved.

ForensicScienceInternational241(2014)102–111

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Forensic

Science

International

moremetabolites.Asallofthesemetaboliteshavethepotentialto affectlarvalgrowth, theeffects of metabolitesof interestcould easilybeoverrated.Theprimarymetabolicproductof metham-phetamine degradation in humans is p- hydroxymethamphet-amine,whichaccountsfor15–50%ofallmetabolitesexcretedin urine [23]. It is itself a potent hallucinogen, and contributes significantlytothehalf-lifeofmethamphetamine[18].However,in non-humananimals,theprimarymetabolicproductsof metham-phetaminebreakdownhavebeenrecordedasp -hydroxynorephe-drineandp-hydroxymethamphetamine(rats),norephedrineand benzoicacidconjugates(guineapigs),andamphetamine(rabbits)

[12,23].

Withtheexceptionofamphetamine[24],nopublishedstudies haveinvestigatedtheeffectsofthesecompoundsonthegrowth ratesofblowflyspecies.Ascertainmetabolitesarealwayspresent in overdose victims [20], necrophagous insects feeding on a cadaverwillingestthem.Theeffectoftheseproductsoninsect metabolicactionneedstobesubstantiatedinordertoprovidea validminimumPMIestimatefordrug-inducedfatalities.

Theeasterngoldenhairedblowfly,Calliphorastygia(Fabricius) (Diptera:Calliphoridae),isamongthemostforensicallyimportant speciesineasternAustralia[25].Itisoneofthefirstspeciespresent at a corpse,usually arriving within hoursto oviposit.Previous studiesontheeffects ofdrugs onthis specieshavefocused on morphine [26,27], with no investigation having been done on stimulantsortheirmetabolites.Wereporthereforthefirsttime the effects of methamphetamine and p -hydroxymethamphet-amineonthegrowthrateoftheblowflyC.stygia,withtheaimof determiningthesuitabilityofthisspeciesasamodelforestimates ofminimumPMIinscenariosinwhichthecorpseiscontaminated withtheseillicitdrugs.

2.Materialsandmethods

Methamphetamine and its primary human metabolite, p-hydroxymethamphetamine, wereappliedto thefood sourceof C.stygialarvaetosimulatepostmortemconditionsin metham-phetamine overdosevictims. Eggs werecollected fromblowfly cultures and assigned randomly to one of ten groups (nine treatments and a control). Calliphora stygia specimens were cultured through a minimum of one generation (maximum of

five generations) from pupae obtained from Sheldon’s Bait (Parawa,Australia). Flieswere keptin plastic cages withmesh lidsat 23C, and exposedtoa photoperiodof 12:12light:dark. Waterandgranulatedsugarwereprovidedadlibitum.

Sheep'sliverwascutinto3cm3piecesandsuppliedtocultures

tofacilitateovarianmaturationinfemaleflies.Thecultures,once sufficientlymatured,werepresentedwithfreshlivercoveredwith athinlayerofcottonwooltoencourageoviposition.Cageswere checkedeverytwohoursandeggstransferredtoaPetridish.Eggs werecountedinto90groupsof150each.Tenexperimentalgroups wereestablishedforfeedinglarvae:(1)control,no methamphet-amine (MA) or p-hydroxymethamphetamine (p-OHMA); (2) 0.1mg/kg methamphetamine (0.1 MA); (3) 1.0mg/kg metham-phetamine(1.0MA);(4)10mg/kgmethamphetamine(10MA);(5) 0.1mg/kg methamphetamine:0.015mg/kg p -hydroxymetham-phetamine(0.1MA:0.015p-OHMA);(6)1.0mg/kg methamphet-amine:0.15mg/kg p-hydroxymethamphetamine (1.0 MA:0.15 p-OHMA); (7) 10mg/kg methamphetamine:1.5mg/kg p -hydroxy-methamphetamine (10 MA:1.5 p-OHMA); (8) 0.015mg/kg p -hydroxymethamphetamine (0.015 p-OHMA); (9) 0.15mg/kg p -hydroxymethamphetamine(0.15p-OHMA);and(10)1.5mg/kg p-hydroxymethamphetamine(1.5p-OHMA).

The control batch containing no methamphetamine was prepared by mixing 15mL of distilled water into 1.5kg of kangaroo mince. Treatments of 10mg/kg,1mg/kg and 0.1mg/

kgmethamphetaminewerepreparedbydissolving15mg,1.5mg and 0.15mg, respectively,of ()-methamphetamine hydrochlo-ridein15mLdistilledwaterandmixinginto1.5kgofkangaroo mince.p-Hydroxymethamphetamineconcentrationsof1.5mg/kg, 0.15mg/kgand0.015mg/kgwerepreparedbydissolving2.25mg, 0.225mgand0.0225mgofp-hydroxymethamphetamine, respec-tively, in 15mL of distilled water and mixing into 1.5kg of kangaroomince.Concentrationsofeachratioofdrug:metabolite were prepared bymixing 2.25mg, 0.225mg, and 0.0225mg of p-hydroxymethamphetaminewith1.5mg,0.15mgand0.015mgof methamphetamine,respectively, in15mLofdistilledwater and 1.5kgofkangaroomincetosimulatethreepostmortemratiosof drugand metaboliteconcentrations.These concentrationswere deemedsuitableforinvestigationsbasedoncommonlyreported self-administereddosesof()-methamphetaminehydrochloride thathaveconsequentlyledtotoxicbodilyconcentrationsofthe druganddeathofmethamphetamineusers[18,28–30].

Each treatment was mixed byhand for 10min,followed by 5minofmixingwithablendertoensureanevendistributionof drug,liquidandmeat,orliquidandmeatonlyforcontrolbatches. Toavoidcontamination,newglovesandmixingcontainerswere usedforeachtreatment,andtheblenderheadrinsedinethanol andflushedwithnearboilingwaterfor10minbetweenuses.Meat batchesweresplitinto150gportionsandplacedintoplasticweigh boats.Batcheswerestoredat20C,andmeatportionsdefrosted asrequiredtoreplenishthelarvalfoodsource.

()-Methamphetamine hydrochloride (99.71.3%) and p-hydroxyamphetaminehydrochloride(p-OHAM)(99.71.3%)were obtainedunderlicensefromtheNationalMeasurementInstitute (NSW,Australia).p-Hydroxyamphetaminehydrochloridewas con-vertedtotheprimaryhumanmetaboliteofmethamphetamine, p-hydroxymethamphetaminehydrochloride,priortoinsectstudies.

Asolutionofp-hydroxyamphetaminehydrochloride(8.49mg) inMilli-Qwater(1mL)wasadjustedtopH12bythedrop-wise addition of sodium hydroxide (10%). The solution was then extracted with CH2Cl2 (210mL), and the combined organic

layers concentrated to give p-hydroxyamphetamine (3.4mg), which was used without further purification. Boc2O (5.4mg)

wasaddedtoasolutionofp-hydroxyamphetamine(3.4mg)inTHF (0.004mL)andEt3N(2.7mg)andthereactionstirredatRTunder

N2 for 24h. CH2Cl2 (2mL) was then added and the mixture

sonicated and the organic layer extracted. This process was repeatedtwiceandthecombinedorganiclayersdried(MgSO4)and

concentratedtogivep-OHAM-Boc(6.3mg,80%yield).Confi rma-tionofthesuccessofthechemicaltransformationcamefrommass spectrometricanalysis,withtheESI-MSspectrumshowingapeak at m/z374 (M+H+), assigned totheprotonated mass of the

p -OHAM-Boc.

Asolutionofp-OHAMP-diBoc(14.3mg)indryTHF(0.5mL)was addeddrop-wiseover5mintoamixtureofNaH(1.45mg,2.42mg from60%NaHstock,1.5eq)indryTHF(1mL)ina5mLflaskunder N2gasandat0C.MeI(0.08mL,17.33mg,3eq)wasthenadded

drop-wiseintothemixture,whichwasstirredfor48hatRT,and thereactionmonitoredbyESIMS.Thereactionwasquenchedwith water (2mL), and the reaction extracted with CH2Cl2, the

combined organic layers dried (MgSO4)and then concentrated

anddriedundervacuumtoobtainN -methyl-4-hydroxymetham-phetamine(14.2mg,96%)asanUVactivepaleyellowpowder;1H

NMR(CDCl3,500MHz),7.14(d,3J=7.3Hz,2H,H20,H40),6.84(d,3J

=7.3Hz,2H,H30andH50),3.78(s,3H,NCH

3),3.39(d,2J=15.1Hz,

H1A),3.33(m,1H,H2),2.80(d,2J=15.1Hz,H1B),1.33(m,3H,H3); 13CNMRCDCl

3,125MHz),158.8(C40),130.4(C20,C60),127.8(C10),

114.3 (C30, C50), 57.4 (C2), 55.3 (NCH

3), 38.6 (C1), 15.6 (C3);

ESIMS,m/z166(M+H+).

Each subset of 150 eggs, collected as above, was placed immediatelyontoasmallpieceofcottonwoolandallocatedto

oneof the tengroups (ninereplicatesof eachgroup in total). Weighboats containing spiked meatwereplaced into 850mL rectangular plastic containers with mesh lids, lined with a shallowlayer(5mmdeep)ofwheatenchaff.Thechaffprovideda medium for the larvae to crawl into when they had finished feeding. All larvae were reared at 23C in a temperature-controlled incubator (Thermoline Scientific, Australia) and exposedtoaphotoperiodof12:12light:dark.Thedayonwhich eggs were laid, collected and distributed to an experimental groupwasdesignatedasday0.Thesamplingdesignofourstudy followed that of George et al. [27], in order to facilitate comparisonwiththeprevioustoxicologicalworkonthisblowfly. Sampleswerethereforecomparedatfourtimepoints.Thefirst two comparison stages took place on days 4 and 7 of experimentation, during the larval stage. Three replicates of eachgroupwereremovedattheday4and7comparisoninterval. Larvae were extracted from the meat and starved for 4h to encourage expulsionof thecontents of the crop.Larvae were killed and fixed by placing in boiling water for 60s and individually washed in near-boiling water for 30s to ensure thatalladhesivesubstratewasremoved.Larvaewerethenstored in80%ethanol,afterwhichtheirlength,widthandweightwere measured.The posteriorspiracles of eachspecimenwere also inspected to record developmental instar. To determine the persistence of methamphetamine and p- hydroxymethamphet-amineinthelarvalfoodsource,1gsamplesof kangaroomince were taken from each group for later analysis using high performanceliquidchromatography.

The third comparison, incorporating a third set of three replicates perexperimental group, was madeduring the pupal stage.Observationsweremadeevery4htoaccuratelyrecordthe dayandhour(wheresuitable)atwhichpupariation(theprocessof puparium formation) began and concluded in each replicate container.Commencementofpupariationwasrecordedatthefirst indicationofcolourchangeoftheprepupafromwhitetoorange. Conclusion of pupariation was denoted by all samples having progressedfromorange todark brown, whereuponthe length, width and weight of all samples were measured. Following measurement,pupaewerereturnedtotheiroriginalcontainersfor eclosion.

The fourthcomparison was madeonceadults had emerged. Observations were made every 4h to record as accurately as possible when emergence began and concluded. The day and averagehourofinitialeclosionwererecorded,aswerethedayand hourofaverageeclosion(P50value).Adultswereremovedfrom plasticcontainersandplacedinafreezerfor5mintoslowtheir movement. Flies were then killed by asphyxiation with ethyl

acetateandstoredin80%ethanol.Measurementsofadultweight weremadewithin4hofcollection.Theleftwingandrearleftleg werethenremovedforlateranalysis.

Larvaeandpupaewereviewedunderadissectingmicroscope (MZ16A,LeicaMicrosystems,Germany).Afibreopticlightsource (CLS150X,LeicaMicrosystems,Germany)wasusedtoilluminate samples on a contrasting background to assist analysis. Each specimenwasphotographedwithadigitalcamera(DFC259,Leica Microsystems, Germany) and Leica Application Suite V3.8 software(LeicaMicrosystems, Germany)employed tomeasure length andwidth parametersto thenearest 0.001mm. Larvae wereviewedlaterally,andtheirlengthsmeasuredbetweenthe mostdistalpointoftheheadandthemostposteriorabdominal segment (Fig. 1(a)). Larval width was measured across the intersectionofthefifthandsixthabdominalsegments. Ultrasen-sitivescales(ML204,MettlerToledo,Switzerland)andLabXdirect balance2.1software(MettlerToledo,USA)wereutilisedtorecord the weightsof each sampleto the closest 0.1mg. Pupae were viewedventrallyandtheirlengthsmeasuredbetweenthemost posterior to most anterior points. Width measurements were obtainedbymeasuringsamplesacrosstheintersectionofthefirst andsecondabdominalsegments(Fig.1(b)).Adultswereremoved fromethanolandallowedtodryfor10minbeforebeingweighed. Wing and leg samples were viewed under the dissecting microscopeand photographed. For each sample, thelength of thecosta(oneoftheperipheralwingveins)andtibia(oneofthe sectionsoftheleg)weremeasuredtogiveanindicationofadult size and to determine if any differences existed between treatments due to drug exposure during earlier life stages (Fig.1(c,d)).

Following measurement, maggots, puparia and adults were individuallygroundusingamortarandpestleandcombinedwith 800

mL

ofdistilledwater(maggotsandadultswereallowedtodry for24hpriortohomogenisation).Cellulardebriswasremovedby precipitationinmethanol(AjaxFinechem,Australia)and centri-fugation(Model5412D, EppendorfSouthPacific,Australia). The solution was run through filter paper to ensure that all large contaminantswereremoved.Smallercontaminantswereremoved by HPLC specific 4mm syringe filters with 0.45mm

polytetra-fluoroethylenemembranes.Sampledmeatwasgroundinamortar andpestleandcombinedwith1000

mL

ofdistilledwater.Cellular debriswasremovedbyprecipitationinmethanoland centrifuga-tionandfilteredasforlarvae,puparialandadultsamples.Aslittle isknownaboutthepharmacokineticsofdrugsofabuseingestedby insects, two standard solutions of methamphetamine were preparedbeforeanyanalysisofsampleswasattemptedinorder todeterminewhichformofmethamphetamine,ifany,waspresentFig.1.(a)LarvaeofCalliphorastygia,showinglengthandwidthmeasurements;(b)C.stygiapupa,showinglengthandwidthmeasurements;(c)leftwingofC.stygia,showing

costallengthmeasurement;(d)rearleftlegofC.stygia,showingtibiallengthmeasurement.

[image:13.595.113.482.564.720.2]inC.stygiasamples.Thefirstwaspreparedbydissolving7mgof ()-methamphetaminehydrochloride in5mLof distilledwater, thus leaving the hydrochloride salt intact. The second was preparedbyneutralising7mgof ()-methamphetamine hydro-chloridewithsodiumhydroxide.Thesolutionwasthen filtered with an HPLC specific syringe filter, and mixed with 5mL methanol.Standardsforp-hydroxymethamphetamine hydrochlo-ridewerepreparedinthesamemanner.Thepresenceorabsenceof methamphetamine was confirmed by high performance liquid chromatography(HPLC)underisocraticconditions.Solventswere acetonitrile(190grade)andwaterandethylamine.Solventswere sonicated in an ultrasonic cleaner (Ultrasonics, Australia) for 20minpriortouse.AnalytesweredetectedbyUVlightat254nm. Thepresenceorabsenceofmethamphetamineorp- hydroxyme-thamphetaminewasrecordedforeachsample.

StatisticalanalysiswasundertakenusingJMPv7forWindows (SAS,USA).NormalityofthedatawasevaluatedusingQ–Qplotsand Kolmogorov–Smirnov normalitytests.Measuredsample param-eters (length, width and weight) were analysed using nested ANOVAs,whichallowedidentificationofsignificancebothbetween groups,and betweenthereplicates ofgroups.Survivorship was investigatedatthelarvaland adultcomparison stages. Kruskal-Wallistestswereusedtodeterminewhethertherehadbeenany appreciablelossinsamplenumbersasaresultoftheirexposureto drugcompounds.Significantresultswerefurtherexaminedwitha Tukey–Kramertesttoassesswhereanydifferenceslay.

3.Results

HPLCchromatogramsqualitativelydeterminedtheabsenceof methamphetaminecompoundsinthecontrolmeat.Thepresence ofmethamphetamineand/orp-hydroxymethamphetamineinthe treatment groups was confirmed by HPLC–UV analysis. These compoundswouldthereforehavebeeningestedbyfeedinglarvae. Developmentratesoflarvaeweredeterminedbyincreasesin thelength and width of sampled specimens. Weight measure-mentswerealsotakentoidentifyanyunusualgrowthpatterns.No obviousdifferencesinaveragetemperaturewerenotedbetween groupsorreplicates.

3.1.Comparisonofday4larvae

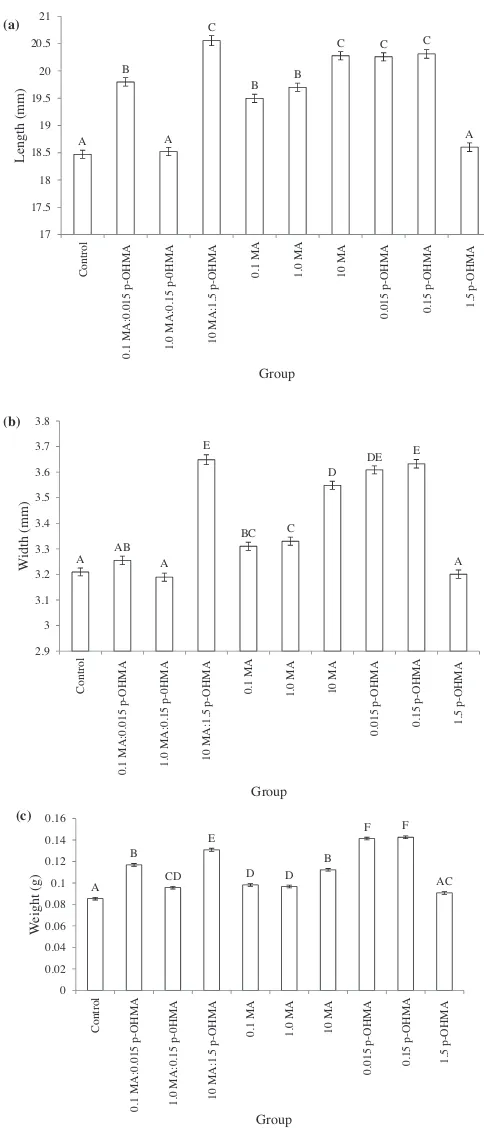

AnestedANOVAofmeanlarvallengthafterfourdaysofgrowth identified significant differences between treatment types (F9, 3485=40.75,p< 0.0001)(Fig.2(a)).

AposthocTukey–Kramertestdeterminedthatthemeanlengths ofeachofthepuremethamphetaminetreatments(0.1MA,1.0MA and10MA)weresignificantly greaterthanthecontrolgroup,aswas themeanlengthoflarvaeexposedtothetwolowerconcentrations ofpuremetabolite(0.015p-OHMAand0.15p-OHMA).Similarly,the twolowermethamphetamine:metaboliteratios(0.01MA:0.015 p-OHMAand1.0MA:0.15p-OHMA)producedlarvaeofsignificantly greaterlengththanthecontrol.Thetreatmentwiththehighest concentrationofp-hydroxymethamphetamine(1.5p-OHMA)and theintermediateratioofmethamphetamine:p- hydroxymetham-phetamine(1.0MA:1.5p-OHMA)werenotsignificantlydifferentin meanlengthfromthecontrolgroup.Significantdifferenceswere also seen between replicates within groups (F20, 3485=16.96,

p< 0.0001).AposthocTukey–Kramertestrevealedtherewasno significantdifferencein meanlengthbetweenreplicateswithin eachgroupexceptforinthecontroland0.15p-OHMAtreatment,for whichallreplicatesweresignificantlydifferentfromeachother.

Similartrendswereobservedinanalysesofmeanreplicatewidth (Fig.2(b)).AnestedANOVAshowedsignificantdifferencesbetween groups(F9,3485=136.29, p< 0.0001). Themean width of larvae exposedtomethamphetamine(0.1MA,1.0MAand 10MA)was

A B

A C

B B

C C C

A 17 17.5 18 18.5 19 19.5 20 20.5 21 Co ntr o l 0 .1 MA :0. 0 1 5 p-O H MA 1.0 MA :0. 1 5 p-0H MA 10 MA:1. 5 p-O HMA 0. 1 MA 1. 0 MA 10 MA 0. 015 p -OHMA 0. 15 p-O HMA 1. 5 p -O H MA Length (m m ) Group (b) (a) (c)

A AB A E BC C D DE E A 2.9 3 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Control 0. 1 MA :0.01 5 p-O HMA 1.0 M A :0 .1 5 p-0 H M A 10 MA:1.5 p

-OHMA 0.1 MA 1.0 MA 10

M A 0.015 p-OHMA 0. 15 p -O HMA 1.5 p-O HMA W idth (m m ) Group A B CD E D D B F F AC 0 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.1 0.12 0.14 0.16 Co ntr o l 0.1 MA :0. 0 1 5 p-O HMA 1.0 MA :0. 1 5 p -0H MA 10 MA:1. 5 p-O H MA

0.1 MA 1.0 MA 10 MA

0.

01

5

p-OHMA

0.15 p-OHMA 1.5 p

-O H MA W eight (g) Group

Fig. 2.Meanlength(a),width(b)andweight(c)(SE)ofday4larvae,exposed

duringdevelopmenttodifferentconcentrationsofmethamphetamineand/or

p-hydroxymethamphetamine.Experimentalgroupsarecontrol;0.1mg/kg

metham-phetamine:0.015mg/kgp-OHMA(0.1MA:0.015p-OHMA);1.0mg/kg

methamphet-amine:0.15mg/kg p-OHMA (1.0 MA:0.15 p-OHMA); 10mg/kg

methamphetamine:0.015mg/kgp-OHMA(10MA:1.5p-OHMA);0.1mg/kg

meth-amphetamine (0.1 MA); 1.0mg/kg methamphetamine (1.0 MA); 10mg/kg

methamphetamine(10MA);0.015mg/kgp-OHMA(0.015p-OHMA);0.15mg/kg

p-OHMA(0.15p-OHMA);1.5mg/kgp-OHMA(1.5p-OHMA).Groupsnotconnected

bythesameletteraresignificantlydifferent.

[image:14.595.314.556.54.618.2]significantlygreaterthanthecontrol.Similarly,themeanwidthsof larvaeinthehighestratiotreatment(10MA:1.5p-OHMA)andthe low and intermediate p-hydroxymethamphetamine concentra-tions(0.015p-OHMAand0.15p-OHMA)weresignificantlygreater thanthecontrolgroup.Bycontrast,themeanwidthsofthelower ratiotreatments(0.1MA:0.015p-OHMAand1.0MA:0.15p-OHMA) and the highest p-hydroxymethamphetamine treatment (1.5 p-OHMA)didnotdiffersignificantlyfromthecontrol.Withthe exception of the control and 0.15 p-OHMA groups, where one replicatedifferedsignificantlyfromtheothertwo(F20,3485=54.07,

p< 0.0001), a post hoc Tukey–Kramer test did not identify significantdifferencesbetweenreplicateswithineachgroup.

A nested ANOVA analysis identified significant differences between the larval groups for mean weight (F9, 3485=100.21,

p< 0.0001). The post hoc Tukey–Kramer test revealed similar trendstolengthandwidthcomparison.Averagelarvalweightsof the methamphetamine (0.1 MA,1.0 MA and 10 MA) and ratio treatments(0.1MA:0.015p-OHMA,1.0MA:0.15p-OHMAand10 MA:1.5p-OHMA)weresignificantlygreaterthanthecontrol.The mean weights of the two lower p-hydroxymethamphetamine treatments(0.015p-OHMAand 0.15p-OHMA)werealsosignifi -cantlygreaterthanthecontrol.Bycontrast,themeanlarvalweight of the highest p-hydroxymethamphetamine treatment (1.5p-OHMA) did not differ significantly from the control (Fig.2(c)).Significantdifferencesbetweenreplicateswithin treat-ments(F20,3485=102.67,p< 0.0001)wereidentifiedbyaposthoc Tukey–Kramertest. However,only one replicateof each of the controland0.1MAgroupsdifferedsignificantlyfromtheothertwo replicateswithinthegroup.

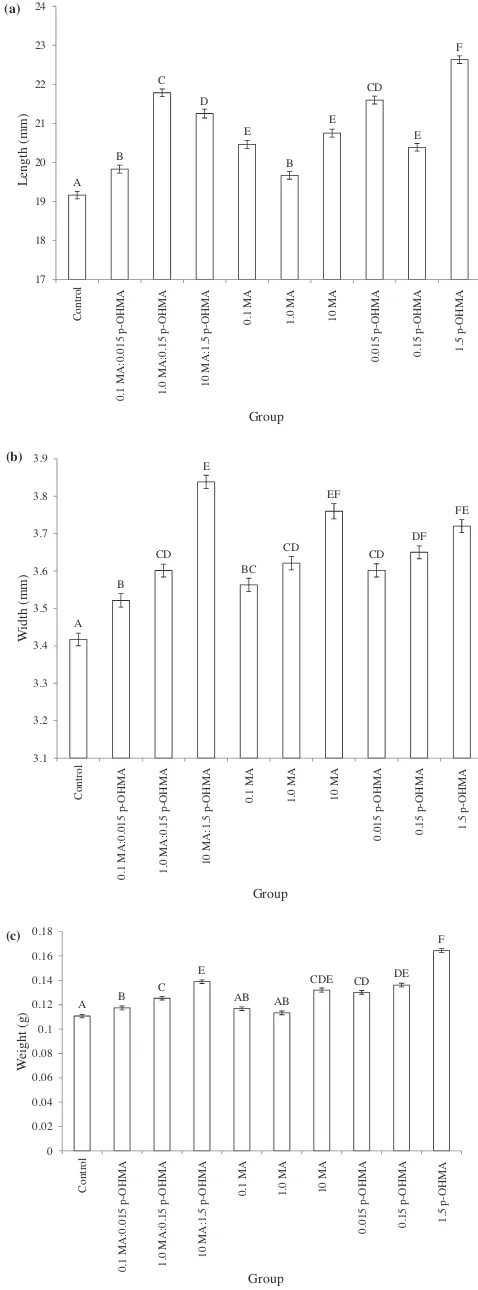

3.2.Comparisonofday7larvae

AnestedANOVAof meanlengthidentifiedsignificant differ-encesbetweentreatments(F9,3485=48.77,p< 0.001Theposthoc Tukey–Kramer test revealed that the mean lengths of larvae exposedtoanydrugcompoundweresignificantlygreaterthanthe control(Fig.3(a)).However,significantvariation between repli-cateswithingroupswasalsodetected(F20,3485=51.05,p< 0.001). Onereplicateofeachofthecontrol,intermediate methamphet-amineconcentration(1.0MA)andthehighestp -hydroxymetham-phetamineconcentration(1.5p-OHMA)wassignificantlydifferent fromtheothertwowithineachgroup.

Substantialvariationwasalsoseenbetweenthemeanreplicate widthsofday7larvae(F9,3080=19.28,p< 0.001)(Fig.3(b)).The mean widths of larvae exposed to any drug treatment were significantlygreaterthanthecontrolgroup.AnestedANOVAof replicatewithintreatment showedthat onereplicateofthe1.5 p-OHMA group differed significantly from the other replicates withinthetreatment(F20,3080=19.10,p< 0.001).

Similarly,nestedANOVAdeterminedthatthelarvaeexposedto methamphetamine compounds were significantly heavier on average than control samples (F9, 3080=65.45, p< 0.001) (Fig. 3(c)). Significant differences were also detected between replicateswithingroups(F20,3080=50.37,p< 0.001).Onereplicate ofeach ofthe1.5p-OHMAand 1.0MA:0.15p-OHMAtreatment groups,andtheintermediatemethamphetaminegroup(1.0MA) weresignificantlydifferentfromtheothertworeplicateswithin theirtreatments.Furthermore,eachreplicateofthecontrolwas significantlydifferentfromeveryother.

(a) (b) (c) A B C D E B E CD E F 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Control 0.

1 MA:0.015 p-O

HMA 1.0 MA :0. 1 5 p -OH MA 10 MA:1.5 p-OHMA 0. 1 MA 1.

0 MA 10 M

A 0.015 p-OH MA 0. 15 p -O H MA 1.5 p-O HMA Length (m m ) Group A B CD E BC CD EF CD DF FE 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Co ntr o l 0.1 MA :0. 0 1 5 p-O HMA 1. 0 MA :0.15 p-O H MA 10 MA:1. 5 p-O H MA

0.1 MA 1.0 MA 10 MA

0. 015 p-OHMA 0. 15 p-O H MA 1. 5 p -O H MA Wi d th ( m m ) Group A B C E AB AB

CDE CD DE F 0 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.1 0.12 0.14 0.16 0.18 Co ntrol 0.1 MA :0.015 p-OHMA 1. 0 MA :0.15 p -OH MA 10 MA:1.5 p-OHMA 0. 1 MA 1.

0 MA 10 MA

0.

015 p-OHMA 0.15 p-O

H MA 1. 5 p -O H MA W eight (g) Group

Fig. 3. Meanlength(a),width(b)andweight(c)(SE)ofday7larvae,exposed

duringdevelopmenttodifferentconcentrationsofmethamphetamineand/or

p-hydroxymethamphetamine.Experimentalgroupsarecontrol;0.1mg/kg

metham-phetamine:0.015mg/kgp-OHMA(0.1MA:0.015p-OHMA);1.0mg/kg

methamphet-amine:0.15mg/kg p-OHMA (1.0 MA:0.15 p-OHMA); 10mg/kg

methamphetamine:0.015mg/kgp-OHMA(10MA:1.5p-OHMA);0.1mg/kg

meth-amphetamine (0.1 MA); 1.0mg/kg methamphetamine (1.0 MA); 10mg/kg

methamphetamine(10MA);0.015mg/kgp-OHMA(0.015p-OHMA);0.15mg/kg

p-OHMA(0.15p-OHMA);1.5mg/kgp-OHMA(1.5p-OHMA).Groupsnotconnected

bythesameletteraresignificantlydifferent.

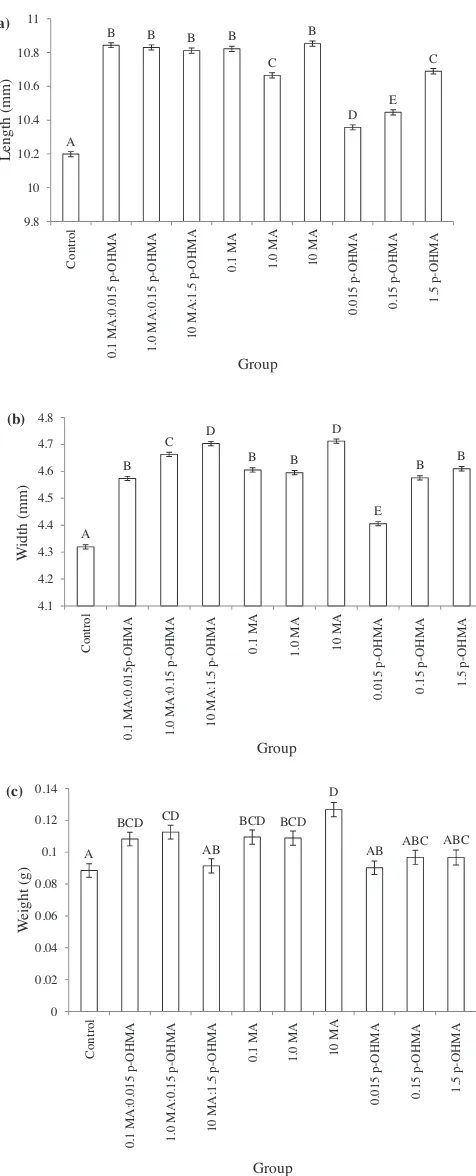

[image:15.595.38.277.59.704.2]3.3.Comparisonofpupae

Statisticalsignificancebetweenthemeanpupallengthsofeach treatment was detected by a nested ANOVA (F9, 3022=87.59,

p< 0.0001).AposthocTukey–Kramertestrevealedthatthemean lengthsofpupaeexposedtoanydrugcompoundweresignificantly longerthanthecontrol(Fig.4(a)).Significantvariationwasalso observed between replicates within each of the groups (F20, 3022=20.10, p< 0.0001). One replicate of the control and eachpuremethamphetaminetreatment(0.1MA,1.0MA,10MA) variedsignificantlyfromtheotherswithineachgroup.

A nested ANOVA of width showed significant differences between groups at the pupal stage (F9, 3022=94.23, p< 0.001) (Fig.4(b)).Themeanwidthsofpupaeexposedtoany metham-phetamineand/or metabolitetreatmentduring thelarval stage weresignificantgreater thanthecontrolsamples.Furthermore, nestedANOVAanalysisidentifiedsignificantvariabilitybetween the mean widths of individual replicates within groups (F20, 3022=97.87, p< 0.001). With the exception of the ratio treatments(0.1MA:0.015p-OHMA,1.0MA:0.15p-OHMAand10 MA:1.5p-OHMA),onereplicateineachtreatmentwassignificantly differentfromtheothertwo. Eachreplicate ofthe controlwas significantlydifferentfromtheremainingtworeplicates.

Whenaverage weightwas compared, significantdifferences were detected between treatments using a nested ANOVA (F9,3022=3.74,p< 0.001)(Fig.4(c)).AposthocTukey–Kramertest ofmean pupalweight showed thatallpuremethamphetamine treatments(0.1MA,1.0MAand10MA)andthetwolowerratio treatments(0.1MA:0.015p-OHMAand1.0MA:0.15p-OHMA)were significantlyheavierthanthecontrolgroup.Furthermore,signifi -cant differences between replicates within groups were also identified (F20,3022=3.68,p< 0.001). The highest methamphet-amine treatment (10 MA) had one replicate that differed significantlyfromtheothertwowithinthetreatment.

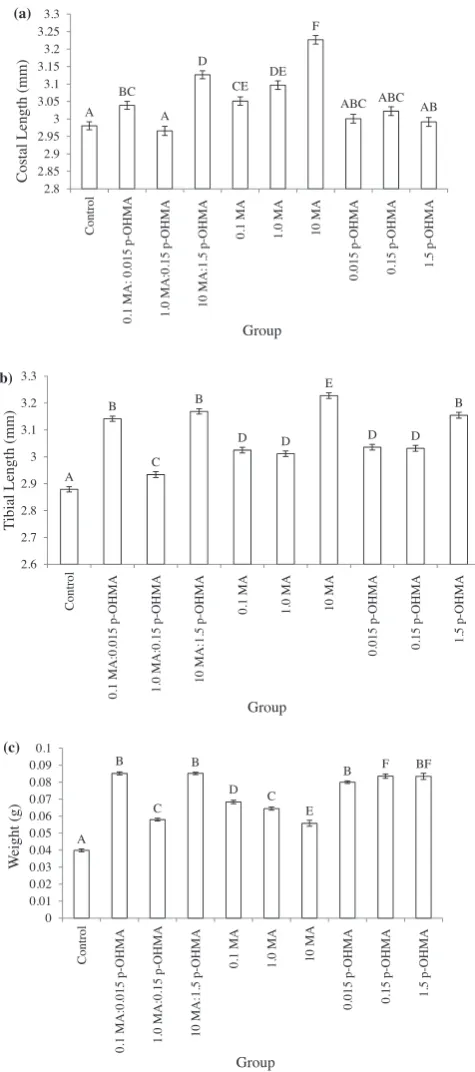

3.4.Comparisonofadults

Onceadultfliesemergedfromthepuparium,theleftwingand rearleftlegwereanalysedtoassessoverallflysize.Thecostalvein of the wingand the tibia of theleg were measured. A nested ANOVAshowed thatthereweresignificantdifferencesbetween themeancostallengthin eachgroup(F9,2755=15.17,p< 0.001) (Fig.5(a)).AposthocTukey–Kramertestidentifiedthatthepure methamphetaminetreatments(0.1MA,1.0MAand10MA),and thelowandhighratiotreatments(0.1MA:0.015p-OHMAand10 MA:1.5 p-OHMA) varied significantly from the control. No significantdifference wasseen betweenthemeancostal length ofreplicateswithingroups(F20,2755=0.14,p=0.87).

Significantdifferencesbetweenmeantibiallengthswerealso detectedbyanestedANOVA(F9,2755=40.22,p< 0.001)(Fig.5(b)). A post hoc Tukey–Kramer test showed that all treatments containing drug compounds produced flies with significantly greatermeantibiallengthsthanthecontrolgroup.Afurthernested ANOVAshowedasignificanteffectofreplicatewithingroup(F20, 2755=3.84,p=0.021)withaposthocTukey–Kramerrevealingone

replicateofeachofthelowestmethamphetaminetreatment(0.1 MA)andthecontrolgroupdifferingsignificantlyfromtheother tworeplicateswithinthesegroups.

The average weights of adult flies were determined to be statisticallydifferentby anestedANOVA(F9,2755=244.43,p< 0.001) (Fig. 5(c)). Apost hocTukey–Kramertestshowed that allflies exposed tomethamphetamineor p-hydroxymethamphetamineas larvae were significantlyheavier than the control samples. A nested ANOVA was used to investigate variability within treatments between replicates.Significantdifferenceswereidentified(F20,2755=11.22,

p< 0.001)andidentifiedbyaposthocTukey–Kramertobebetween

A

B B B B

C B D E C 9.8 10 10.2 10.4 10.6 10.8 11 Contro l 0.1 MA :0. 0 15 p-OHMA 1. 0 MA :0.15 p-OH MA 10 MA:1.5 p-OHMA 0.

1 MA 1.0 MA 10 MA

0.01

5

p-OH

MA

0.15 p-OHMA 1.

5 p -O H MA Length (m m ) Group (a) (b) A B C D B B D E B B 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Control 0.1 MA :0. 0 15p-OH M A 1.0 MA :0. 1 5 p-OH MA

10 MA:1.5

p-OHMA 0.1 MA 1.0 MA 10 MA

0. 01 5 p-OH M A 0. 15 p-OHMA 1.5 p-O HMA W idth (m m ) Group (c) A BCD CD AB BCD BCD D

AB ABC ABC

0 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08 0.1 0.12 0.14 Co n tr o l

0.1 MA:0.015 p-OHMA 1.0 MA:

0 .15 p-OHMA 10 MA:1.5 p-OHMA 0. 1 MA 1.

0 MA 10 M

A 0.01 5 p-OH MA 0. 15 p -OHMA 1. 5 p -O H MA W eight (g) Group

Fig. 4.Meanlength(a),width(b)andweight(c)(SE)ofpupae,exposedduring

developmenttodifferentconcentrationsofmethamphetamineand/or

p-hydro-xymethamphetamine.Experimentalgroupsarecontrol;0.1mg/kg

methamphet-amine:0.015mg/kg p-OHMA (0.1 MA:0.015 p-OHMA); 1.0mg/kg

methamphetamine:0.15mg/kgp-OHMA(1.0MA:0.15p-OHMA);10mg/kg

meth-amphetamine:0.015mg/kgp-OHMA (10MA:1.5 p-OHMA);0.1mg/kg

metham-phetamine (0.1 MA); 1.0mg/kg methamphetamine (1.0 MA); 10mg/kg

methamphetamine(10MA);0.015mg/kgp-OHMA(0.015p-OHMA);0.15mg/kg

p-OHMA(0.15p-OHMA);1.5mg/kgp-OHMA(1.5p-OHMA).Groupsnotconnected

bythesameletteraresignificantlydifferent.

[image:16.595.318.556.61.649.2]thereplicatesofthecontrol,0.1MA,1.0MA,10MAand0.15p-OHMA groups.Withinthecontroland10MAgroups,theaverageweightof eachreplicatewasstatisticallyindependent.For0.1M,1.0MAand

0.15 p-OHMA treatments, only one replicate was statistically significantfromtheothertworeplicatesofthetreatment.

3.5.Survivorship

Kruskal–Wallisanalysisofsurvivorshipshowednosignificant difference in the number of larvae surviving after four days (X92=3.54,p>0.432).However,attheday7intervaltherewasa

significantdifferencein survivorshipbetweendrugand control groups (X92=28.01, p =0.017).When compared to the control,

larval numbers had decreased in all pure methamphetamine (0.1MA,1.0MAand10MA),andratiotreatments(0.1MA:0.015 p-OHMA,1.0MA:0.15p-OHMAand10MA:1.5p-OHMA)butnotin the treatments feeding on substrates spiked with pure p-hydroxymethamphetamine(0.015p-OHMA,0.15p-OHMAand 1.5p-OHMA).Adultsurvivorshipwasalsosignificantlydifferent betweentreatments(X92=29.00,p< 0.001).Thenumberofadult

flies remaining in each drugged treatment was significantly smallerthanthenumberofsamplessurvivinginthecontrol.

3.6.Developmentrates

Changesingrowth rateduetothepresenceof methamphet-amineandp-hydroxymethamphetamineinthelarvalfoodsource weredeterminedbyrecording,tothenearesthour,whensamples in each replicate commenced and completed pupariation, and began and completedadult emergence.Calliphora stygia larvae exposedtoanyconcentrationofmethamphetamineorp- hydrox-ymethamphetamine proceeded to show accelerated growth, commencing pupariation significantly before control larvae (F2,10=144.03, p< 0.0001) (Fig. 6). This discrepancy was most obviousin the10 MAand 10MA:1.5 p-OHMA treatments. The initialcolourchangeoftheprepupaefromwhitetoorangebegan 44hearlierinthesetreatmentsthaninthecontrol.

Pupariationwasalsocompleteinallmethamphetamine-and metabolite-treated pupae significantly before the control (F2,10=293.47, p< 0.0001).Samplesthenremainedaspupaefor significantly longer in treatments containing drug compounds (F2,10=441.63,p< 0.0001),andemergedlaterthancontrolsamples (F2, 10=91.47, p< 0.0001). The 10 MA:1.5 p-OHMA treatment showedthegreatestincongruityfromthecontrol.Emergencein this treatment began 34h following the first control samples, equatingtoa78htotaldifferenceindevelopmentrate.

(a) A BC A D CE DE F

ABC ABC AB

2.8 2.85 2.9 2.95 3 3.05 3.1 3.15 3.2 3.25 3.3 Co ntr o l 0.1 MA

: 0.015 p-OH

MA

1.

0 MA

:0.15 p-OHMA

10 MA:1.5

p-OHMA 0.1 MA 1.0 MA

10 MA 0. 015 p-OHMA 0. 15 p -O H MA 1.5 p-OH MA

Costal Length (m

m ) Group (b) A B C B D D E D D B 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 3 3.1 3.2 3.3 C ont ro l 0. 1 MA :0.015 p-OHMA 1.0 M A :0 .1 5 p-O H M A 10 MA:1.5 p-OHMA 0. 1 MA 1.

0 MA 10 M

A 0. 01 5 p-OHMA 0.15 p-O H MA 1. 5 p-OH MA T

ibial Length (m

m ) Group (c) A B C B D C E

B F BF

0 0.01 0.02 0.03 0.04 0.05 0.06 0.07 0.08 0.09 0.1 Control 0. 1 MA :0. 0 15 p-O HMA 1. 0 MA :0.15 p-OHMA 10 MA:1.5

p-OHMA 0.1 MA 1.0 MA 10 MA

0.01 5 p-OHMA 0. 15 p-O H MA 1.5 p-O H MA We ig h t ( g ) Group

Fig.5.Meancostallength(a),tibiallength(b)andweight(c)(SE)ofadults,

exposedduringdevelopmenttodifferentconcentrationsofmethamphetamine

and/orp-hydroxymethamphetamine.Experimentalgroupsarecontrol;0.1mg/kg

methamphetamine:0.015mg/kg p-OHMA (0.1 MA:0.015 p-OHMA); 1.0mg/kg

methamphetamine:0.15mg/kgp-OHMA(1.0MA:0.15p-OHMA);10mg/kg

meth-amphetamine:0.015mg/kg p-OHMA (10 MA:1.5 p-OHMA);0.1mg/kg

metham-phetamine (0.1 MA); 1.0mg/kg methamphetamine (1.0 MA); 10mg/kg

methamphetamine(10MA);0.015mg/kgp-OHMA(0.015p-OHMA);0.15mg/kg

p-OHMA(0.15p-OHMA);1.5mg/kgp-OHMA(1.5p-OHMA).Groupsnotconnected

bythesameletteraresignificantlydifferent.

Fig. 6.Developmentrates of Calliphorastygia samples exposed to different

concentrationsofmethamphetamineand/orp-hydroxymethamphetamine.

Exper-imentalgroupsare control;0.1mg/kgmethamphetamine:0.015mg/kgp-OHMA

(0.1MA:0.015p-OHMA);1.0mg/kgmethamphetamine:0.15mg/kgp-OHMA(1.0

MA:0.15p-OHMA);10mg/kgmethamphetamine:0.015mg/kgp-OHMA(10MA:1.5

p-OHMA);0.1mg/kgmethamphetamine(0.1MA);1.0mg/kgmethamphetamine

(1.0MA);10mg/kgmethamphetamine(10MA);0.015mg/kgp-OHMA(0.015

p-OHMA);0.15mg/kgp-OHMA(0.15p-OHMA);1.5mg/kgp-OHMA(1.5p-OHMA).

[image:17.595.41.279.113.650.2] [image:17.595.303.556.527.667.2]3.7.HPLCanalysis

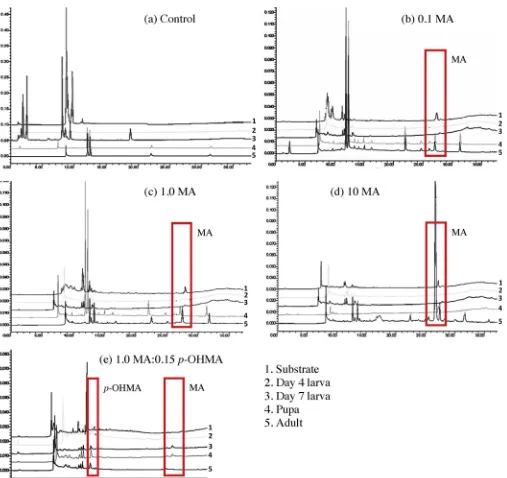

Standardsformethamphetaminehydrochlorideandp- hydrox-ymethamphetamine hydrochloride were established for HPLC underisocraticconditions,withtheformer showingaretention timeof27.3minandthelatter14.2min.Analysisofsamplesofeach lifestagebyHPLCwithUVdetectionqualitativelyconfirmedthe absenceofmethamphetamineandp-hydroxymethamphetamine inthefeedingsubstrateofthecontrol(Fig.7).

Methamphetamine could not be detected in homogenised larvalsamplesoftreatments0.1MA,1.0MAor10MA.However, HPLCchromatogramsqualitativelyconfirmeditspresenceinpupal and adult samples (Fig. 7). p-Hydroxymethamphetamine was detected in larval, pupal and adult preparations of treatments

0.015p-OHMA,0.15p-OHMAand1.5p-OHMA.Inratiotreatments 0.1 MA:0.015p-OHMA,1.0 MA:0.15p-OHMA and10MA:1.5 p-OHMA,onlyp-hydroxymethamphetaminecouldbedetected.

4.Discussion

Inthisstudy,methamphetamine-spikedkangaroomeatwas utilisedtosimulatethepostmortemenvironmentofa metham-phetamineoverdose.Kangaroomincewasselectedinfavourofa live laboratoryanimal as the major andminor metabolites of methamphetamine and absorption and excretion rates are knowntovarybetweenvertebratespecies[20].Theapplication of drugor metabolitedirectlytothemeatensuredthatlarvae were exposed to known concentrations and types of drug

Fig.7.SelectedexamplesofHPLCtracesqualitativelyshowingthepresenceorabsenceofmethamphetamine(MA)andp-hydroxymethamphetamine(p-OHMA):(a)control;

(b)0.1MA;(c)1.0MA;(d)10MA;and(e)1.0MA:0.15p-OHMA.

[image:18.595.52.559.235.713.2]compound,a recognised issuein entomotoxicological research

[31]. Sustained mixingensured a homogenous distribution of methamphetamineand/orp-hydroxymethamphetamine.

Thesecompoundswerefoundtosignificantlyalterthesizeofall lifestagesat theconcentrations investigated.After fourdaysof growth,larvaeinalltreatments,withtheexceptionofthehighest p-hydroxymethamphetamine (1.5p-OHMA) and the intermediate ratiotreatments(1.0MA:0.15p-OHMA),werelonger,widerand heavierthanthecontrolsamples.After sevendays,samples exposed toanymethamphetaminetreatmenthaddevelopedintosignifi -cantlylonger,widerandheavierlarvaethanthecontrolmaggots.

Thesefindingscontrastwiththose ofGoffetal.[12] intheir studies of the flesh fly Sarcophaga ruficornis. When reared on methamphetamine-dosed rabbit tissues,individuals exposed to thehighestconcentrationsofthedrugweresignificantlyshorterin lengththan control samples.This may have resulted fromthe different metabolism of methamphetamine in flesh flies and blowfliesand highlights theinadvisabilityof extrapolating out-comesfromentomotoxicologicalstudiesbetweenspecies.

Inforensicpractice,thelengthsofthelargestlarvaesampled fromabodyareusedtoestimatetheageoftheoldestspecimens, andhence,giveanestimateoftheminimumPMI[32].Theresults ofthis studystronglysuggestthat,in amaggot-infestedcorpse containingmethamphetamine,thelengthof alarva ofC. stygia might not necessarily be a valid indication of its age. If this enhancedgrowthis notconsidered,estimatesof minimumPMI basedonthelarvalstagesofC.stygiacouldbeerroneous.

Furthermore, the presence of methamphetamine and p-hydroxymethamphetamineinthefeedingsubstratesignificantly affectedthegrowthratesofC.stygialarvaeattheconcentrations investigated. The onset of pupariation, and its duration, was significantlyalteredindrug-exposedtreatments.Calliphorastygia larvaeexposed tothese compounds as immaturesreachedthe pupalstageupto44hpriorto,andremainedaspupaeupto34h longerthan controls, a total divergenceof 78h. These findings againcontrastwiththoseofGoffetal.[12],whofoundtheduration ofthepupalperiodofS.ruficornistobesignificantlyshorterthan thecontrolforallsamplesexposedtomethamphetamineduring thelarvalstage.Additionally,thepreviousstudyonC.stygiaby Georgeetal.[27]foundthatitsdevelopmentwasunaffectedby puremorphineatsub-lethal,lethal,andtwice-lethaldoses.These contradictoryfindingsaremostlikelyduetothedifferenttypeof drugusedineachstudy,andtheeasewithwhichtheyareabsorbed bythetissuesofanorganism.

While morphineisapotentanalgesic[33],andrepressesthe centralnervoussystem [34], methamphetamineis a psychosti-mulant [35]. In humans,it immediately induces an increase in metabolismandthereleaseof‘pleasure’neurotransmitters[18]. Althoughbothtypesofdrugarewatersoluble,morphineispoorly solubilisedinlipids[33],whereasbothmethamphetamineand p-hydroxymethamphetaminearehighlylipidsoluble[36]. Metham-phetamine compounds may therefore be better suited to the internal environment of blowfly larvae, which have a high fat content[37].Itispossiblethatthesecompoundsareabletocross thelipid bi-layer of larval cells and accelerate metabolism.An increaseinmetabolicratecouldmanifestasanacceleratedrateof development,orenlargedlarvae,pupaeandadults,whichwereall observedinthecurrentstudy.

ComparedwiththefindingsofGeorgeetal.[27],asignificant differenceinsurvivorshipwasrecordedbetweendrugtreatments andcontrols.Therewas asignificantdecreaseinthenumberof larvaeinall methamphetamine-spikedtreatmentsafter 7days. Similarly,overallsurvival,calculatedonceallflieshademerged, showedthat there were significantly fewer flies in treatments exposedtomethamphetamineasimmatures. Thissuggeststhat methamphetamine compounds have a toxic effect onC. stygia

larvae at any concentration,and mayinfluence their ability to undergometamorphosis.

Methamphetamine and p-hydroxymethamphetamine were detected both in meat and C. stygia samples. HPLC analysis confirmed that methamphetamine and/or p- hydroxymetham-phetaminewere absentfrom thecontrolgroup, but presentin thelarvalfoodsourceoftheremainingtreatments.Consequently, larvaewouldhaveingestedthedrugcompounds.However,when larvaesampledatthefirstandsecondcomparisonintervalswere analysed with HPLC–UV, methamphetamine could not be detected. These findings differed from those of Wilson et al.

[38]intheirstudiesofCalliphoravicina.Whenrearedonskeletal musclefromasuicidaloverdoseofco-proxamolandamitriptyline, amitriptylineanditsactivehumanmetabolite,nortriptyline,were bothdetectedinC.vicinalarvae.

Thisnegativedetectionmayhavebeenduetothewayinwhich sampleswerepreparedforanalysis. Larvaewereground witha mortarandpestleandcombinedwithdistilledwatertosolubilise anycellularmaterialreleased.Thiswasarelativelycrudemethod of homogenization and the complete lysis of all cells, and the releaseofstoredmethamphetamine,wasnotguaranteed.Studies byKinnearetal.[39]haveshownthattheconcentrationoflipidsin C. stygia larvae increases sharply between days 3 and 6 of development, before decreasing after day 7. As larvae were sampled ondays 4 and day 7, within this period of increased lipid production, increased fat content, combined with poor homogenizationtechniques,couldberesponsiblefortheabsence ofmethamphetamineinlarvalpreparationsanalysedbyHPLC.

Itisalsopossiblethatdrugcompoundswerenotdetectedinlarval samplesduetothelowersensitivityofHPLC–UV,whencomparedto chemiluminescenceorfluorescencedetection[40].Takayamaetal., in their studieson methamphetaminedepositsin hair,wereunable to detectmethamphetamineinsmallhairsampleswhenUVdetection wasemployed.However,minuteamountsofthedruginsinglehairs were able to be isolated and detected by chemiluminescence techniques[41].Theuseofalternatedetectionmethodsmightyield moreconclusiveresultsinfuturestudies.

Although the results of the present studyare notable, it is recommended that further investigations at different temper-atures,and alternativeconcentrationsof methamphetamine,be carriedouttoformacomprehensivebankofdataagainstwhich forensiccasescan becompared.As corpsesare rarelyfoundin environmentswithstabletemperatures,agreaterunderstanding oftheeffectsofmethamphetamineatdifferenttemperaturescould assistwithinterpretingforensiccases.Similarly,thepostmortem concentrationsofdrugsinacorpsemayvaryaccordingtotissue type andlocation[42,43]and alsomaydifferfromthe concen-trationsatthetimeofdeathduetopostmortemredistributionby passivereleasesfromthedrugreservoirsof thegastrointestinal tract,lungsandmyocardium,oratlaterstages,fromtheautolysis ofcellsandputrefactionprocesses[44,45].Basiclipophilicdrugs, suchasmethamphetamine,appeartobeparticularlysusceptibleto postmortemredistributionprocesses [44].Itis alsoknownthat larvalgrowthcanbeinfluencedbytissuetypeandageinanimal models[46–48].Therefore,furtherinvestigationoftheeffectsof methamphetamine on blowfly larvae must be carried out at different concentrations and in different substrates for its influence to be conclusively understood. Of course, once a comprehensivesetofdataisavailableforC.stygia,theinfluence ofthisdrugonotherflyspeciesofforensicimportancewouldalso needtobeinvestigated.

5.Conclusions

These findings hold significance for forensic science with particular regard tominimum PMI calculations usingflies. The

alteredgrowthexhibitedinthisstudysuggeststhatanyestimateof minimumPMIbasedonthenormalratesofC.stygiadevelopment at23Ccouldbeoverestimatedbyupto44hwhenbasedonthe larval stage,and by up to78hwhen based onpupal samples. Indeed, because of the resultant developmental acceleration, cautionshouldbeexercisedwheneverC.stygiaisusedtoestimate the minimum PMI of methamphetamine-dosed corpses. The developmental changes of this species of blowfly are also yet unknownattemperatures,drugconcentrationsandinsubstrates otherthanthoseusedhere.Furtherresearchisthereforeessential tomorecomprehensivelyunderstandtheeffectsof methamphet-amineon blowfly development. Until then, C.stygia cannot be assumedtobeareliablemodelforagingcorpsescontainingthis drug.

Acknowledgements

Thisresearchwasmadepossiblebythefinancialsupportofthe AustralianResearchCouncil,theAustralianFederalPolice,theNew SouthWales PoliceForceand UOW’sInstitutefor Conservation BiologyandEnvironmentalManagement.ASNthanksUOWforthe provision of a UPA scholarship. We thank Melanie Archer (Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine) for useful initial discussions,ThaoDangand GregoryTarrant(National Measure-mentInstitute)foradviceandsupplyoftheMAandp-OHMA,and AidanJohnson(UOW)forstatisticalassistance.

References

[1]C.P.Campobasso,F.Introna,Theforensicentomologistinthecontextofthe forensicpathologist'srole,ForensicSci.Int.120(2001)132–139.

[2]J.Amendt,C.S.Richards,C.P.Campobasso,R.Zehner,M.J.R.Hall,Forensic entomology:applicationsandlimitations,ForensicSci.Med.Pathol.7(2011) 379–392.

[3]J.Amendt,R.Krettek,R.Zehner,Forensicentomology,Naturwissenschaften91 (2004)51–65.

[4]M.A.O'Flynn,Thesuccessionandrateofdevelopmentofblowfliesincarrionin southernQueenslandandtheapplicationofthesedatatoforensicentomology, Aust.J.Entomol.22(1983)137–148.

[5]G.S. Anderson, Minimum and maximum development rates of some forensicallyimportant Calliphoridae (Diptera),J. Forensic Sci. 45(2000) 824–832.

[6]M.S.Archer,R.B.Bassed,C.A.Briggs,M.J.Lynch,Socialisolationanddelayed discoveryofbodiesinhouses:thevalueofforensicpathology,anthropology, odontologyandentomologyinthemedico-legalinvestigation,ForensicSci. Int.151(2005)259–265.

[7]S.E.Donovan,M.J.R.Hall,B.D.Turner,C.B.Moncrieff,Larvalgrowthratesofthe blowfly,Calliphoravicina,overarangeoftemperatures,Med.Vet.Entomol.20 (2006)106–114.

[8]M.L.Goff,W.D.Lord,Entomotoxicology:anewareaforforensicinvestigation, Am.J.ForensicMed.Pathol.15(1994)51–57.

[9]F.Introna,C.P.Campobasso,M.L.Goff,Entomotoxicology,ForensicSci.Int.120 (2001)42–47.

[10]L.M.L. Carvalho,Toxicology and forensic entomology,in: J. Amendt, C.P. Campobasso,M.L.Goff,M.Grassberger(Eds.),CurrentConceptsinForensic Entomology,Springer,Dordrecht,2010.

[11]M.Gosselin,V.DiFazio,S.M.R.Wille,M.D.M.RamírezFernandez,N.Samyn,B. Bourel,P.Rasmont,Methadonedeterminationinpupariaanditseffectonthe developmentofLuciliasericata(Diptera,Calliphoridae),ForensicSci.Int.209 (2011)154–159.

[12] M.L.Goff,W.A.Brown,A.I.Omori,Preliminaryobservationsoftheeffectof methamphetamine in decomposing tissues on the developmentrate of

Parasarcophagaruficornis(Diptera:Sarcophagidae)andimplicationsofthis effectontheestimationsofpostmortemintervals,J.ForensicSci.37(1992) 867–872.

[13]E.Musvasva,K.A.Williams,W.J.Muller,M.H.Villet,Preliminaryobservations ontheeffectsofhydrocortisoneandsodiummethohexitalondevelopmentof

Sarcophaga (Curranea) tibialis Macquart (Diptera: Sarcophagidae), and implications for estimating postmortem interval, Forensic Sci. Int.120 (2001)37–41.

[14]H.Kharbouche,M.Augsburger,D.Cherix,F.Sporkert,C.Giroud,C.Wyss,C. Champod,P.Mangin,Codeineaccumulationandeliminationinlarvae,pupae, andimagooftheblowflyLuciliasericataandeffectsonitsdevelopment,Int.J. Leg.Med.122(2008)205–211.

[15]S.Yan-Wei,L.Xiao-Shan,W.Hai-Yang,Z.Run-Jie,Effectsofmalathiononthe insectsuccessionandthedevelopmentofChrysomyamegacephala(Diptera:

Calliphoridae) in the field and implications for estimating postmortem interval,Am.J.ForensicMed.Pathol.31(2010)46–51.

[16]L.M.L.deCarvalho,A.Z.Linhares,F.A.B.Palhares,Theeffectofcocaineonthe development rate of immatures and adults of Chrysomya albiceps and

Chrysomyaputoria(Diptera:Calliphoridae)anditsimportancetopostmortem intervalestimate,ForensicSci.Int.220(2012)27–32.

[17]T.Nagata,K.Kimura,K.Hara,K.Kudo,Methamphetamineandamphetamine concentrationsinpostmortemrabbittissues,ForensicSci.Int.48(1990)39–47. [18]T.E. Albertson,R.W.Derlet,B.E.VanHoozen, Methamphetamineand the expandingcomplicationsofamphetamines,West.J.Med.170(1999)214–219. [19]S.Darke,S.Kaye,R.McKentin,J.Duflou,Majorphysicalandpsychological

harmsofmethamphetamineuse,DrugAlcoholRev.27(2008)253–262. [20]T.Yamamoto,R.Takano,T.Egashira,Y.Yamanaka,Metabolismof

metham-phetamine, amphetamine and p-hydroxymethamphetamine by rat-liver microsomalpreparationsinvitro,Xenobiotica14(1984)867–875. [21]I.delaPena,H.Ahn,J.Choi,C.Shin,J.Ryu,J.Cheong,Reinforcingeffectsof

methamphetamine in an animal model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder-thespontaneouslyhypertensiverat,Behav.BrainFunct.6(2010)72. [22]G.D.Ellison,M.S.Eison,Continuousamphetamineintoxication:ananimal

modeloftheacutepsychoticepisode,Psychol.Med.13(1983)751–761. [23]J.Caldwell,L.G.Dring,R.T.Williams,Metabolismof[14C]methamphetaminein

man,theguineapigandtherat,Biochem.J.129(1972)11–22.

[24]M.R.Peace,ForensicEntomotoxicology:AStudyintheDepositionandEffects ofAmphetaminesandBarbituratesintheLarvaeoftheBlackBlowFly,Phormia regina,Ph.Dthesis,VirginiaCommonwealthUniversity,Virginia,2005. [25]G.W. Levot, Insect fauna used to estimate the post-mortem interval of

deceasedpersons,Gen.Appl.Ent.32(2003)31–39.

[26]S.l.Parry,S.M.Linton,P.S.Francis,M.J.O’Donnell,T.Toop,Accumulationand excretionofmorphinebyCalliphorastygia,anAustralianblowflyspeciesof forensicimportance,J.InsectPhysiol.57(2011)62–73.

[27]K.A.George,M.S.Archer,L.M.Green,X.A.Conlan,T.Toop,Effectofmorphineon thegrowthrateofCalliphorastygia(Fabricius)(Diptera:Calliphoridae)and possibleimplicationsforforensicentomology,ForensicSci.Int.193(2009)21–

25.

[28]S.B.Karch,B.G.Stephens,C.H.Ho,Methamphetamine-relateddeathsinSan Francisco,J.ForensicSci.44(1999)359–368.

[29]G.Rivière,W.B.Gentry,S.M.Owens,Dispositionofmethamphetamineandits metaboliteamphetamineinbrainandothertissuesinratsafterintravenous administration,J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther.292(2000)1042–1047.

[30]O.H.Drummer,Postmortemtoxicologyofdrugsofabuse,ForensicSci.Int.142 (2004)101–113.

[31]M.Gosselin,S.M.R.Wille,M.delMarRamírezFernandez,V.DiFazio,N.Samyn, G. De Boeck, B. Bourel, Entomotoxicology, experimental set-up and interpretationforforensictoxicologists,ForensicSci.Int.208(2011)1–9. [32]B.Greenberg,J.C.Kunich,EntomologyandtheLaw,CambridgeUniversity

Press,Cambridge,2002.

[33]L.L.Christrup,Morphinemetabolites,ActaAnaesthesiol.Scand.41(1997)116–

122.

[34]S.Darke,W.Hall,S.Kaye,J.Ross,J.Duflou,Hairmorphineconcentrationsof fatalheroinoverdosecasesandlivingheroinusers,Addiction97(2002)977–

984.

[35]M. Ferrucci, L. Pasquali, A. Paparelli, S.Ruggieri, F.Fornai, Pathways of methamphetaminetoxicity,Ann.N.Y.Acad.Sci.1139(2008)177–185. [36]L.E.Gaudette,B.B.Brodie,Relationshipbetweenthelipidsolubilityofdrugs

andtheiroxidationbylivermicrosomes,Biochem.Pharmacol.2(1959)89–96. [37]L.L.Keeley,Endocrineregulationoffat-bodydevelopmentandfunction,Ann.

Rev.Entomol.23(1978)329–352.

[38]Z.Wilson,S.Hubbard,D.J.Pounder,Druganalysisinflylarvae,Am.J.Forensic Med.Pathol.14(1993)118–120.

[39]J.F.Kinnear,M.D.Martin,J.A.Thomson,G.J.Neufeld,Developmentalchangesin thelatelarvaofCalliphorastygiaI.Haemolymph,Aust.J.Biol.Sci.21(1968) 1033–1046.

[40]N. Takayama, R. Iio, S. Tanaka, S. Chinaka, K. Hayakawa, Analysis of methamphetamine and its metabolites in hair, Biomed. Chromatogr.17 (2003)74–82.

[41]N.Takayama,S.Tanaka,K.Hayakawa,Determinationofstimulantsinasingle humanhairsamplebyhigh-performance liquidchromatographicmethod withchemiluminescencedetection,Biomed.Chromatogr.11(1997)25–28. [42]C.P.Campobasso,M.Gherardi,M.Caligara,L.Sironi,F.Introna,Druganalysisin

blowflylarvaeinhumantissues:acomparativestudy,Int.J.Leg.Med.118 (2004)210–214.

[43]K.R.Williams,D.J.Pounder,Site-to-sitevariabilityofdrugconcentrationsin skeletalmuscle,Am.J.ForensicMed.Pathol.18(1997)246–250.

[44]F.Moriya,Y.Hashimoto,Redistribution ofmethamphetamineintheearly postmortemperiod,J.Anal.Toxicol.24(2000)153–154.

[45]A.L. Pelissier-Alicot, J.M. Gaulier, P.Champsaur, P. Marquet, Mechanisms underlyingpostmortemredistributionofdrugs:areview,J.Anal.Toxicol.27 (2003)533–544.

[46]G.Kaneshrajah,B.Turner,Calliphoravicinalarvaeatdifferentratesondifferent bodytissues,Int.J.Leg.Med.118(2004)242–244.

[47]J.F.Wallman,D.M.Day,Influenceofsubstratetissuetypeonlarvalgrowthin

CalliphoraaugurandLuciliacuprina(Diptera:Ca