FEEDING ECOLOGY OF LONG-TAILED MACAQUES

AT CIKAKAK MONKEY PARK

ISLAMUL HADI

GRADUATE SCHOOL

BOGOR AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY

BOGOR

STATEMENT OF RESEARCH ORIGINALITY

This is to verify that the thesis entitled :

Feeding Ecology of Long-tailed Macaques at Cikakak Monkey Park

Is my own work which has never previously been published. All of the incorporated data and information are valid and stated clearly

Bogor, 28 November 2005

ABSTRACT

ISLAMUL HADI. Feeding Ecology of Long-tailed Macaques at Cikakak Monkey Park. Under supervision of BAMBANG SURYOBROTO and R. R. DYAH PERWITASARI.

Long-tailed macaques in Cikakak Monkey Park obtain their food both from natural and human sources. They were recorded to consume 41 food items. Analysis using variables party size on foraging and feeding duration showed proportion of natural foods is greater than artificial foods. The averages were 76,39% and 23,61%, respectively. Based on the part eaten of natural foods, troop of macaques in this park consumed almost on young leaves and fruits. They consume and spend much time on young leaves of bamboo (Gigantochloa apus) and fruits from bulu (Ficus virens) and sadang (Corypha elatta). They also obtain food by raiding the crops from agricultural fields those surround the park. Insects were also consumed by them. The visitors and the caretakers of the park gave food, mainly peanuts. Juveniles and sub-adults of long-tailed macaques in this park exploited more various food items than those adults. They also drunk nira (raw coconut sap) from harvesting tubes in coconut trees. Therefore, they were regarded as omnivorous since they can exploit various kinds of food that available in time. ..

ABSTRAK

ISLAMUL HADI. Ekologi Makan Monyet Ekor Panjang di Taman Kera Cikakak. Dibimbing oleh BAMBANG SURYOBROTO dan R.R. DYAH PERWITASARI.

Monyet ekor panjang di Taman Kera Cikakak memperoleh makanan dari alam dan pengunjung sebanyak 41 jenis. Berdasarkan jumlah individu (party size) dan durasi makan, proporsi makanan dari alam lebih besar daripada yang diberikan oleh pengunjung. Proporsi ini masing-masing 76,39% dan 23,61%. Berdasarkan bagian yang dimakan pada makanan dari alam, monyet ekor panjang di tempat ini lebih banyak mengkonsumsi daun muda bambu ( Gigantochloa apus), buah jerakah bulu ( Ficus virens) dan sadang (Corypha elatta). Selain dari wilayah Taman Kera Cikakak, mereka juga mendapatkan makanan dari sawah dan kebun masyarakat Cikakak di sekitar taman. Monyet-monyet di sini juga mendapatkan makanan dari pengunjung dan penjaga makam. Makanan utama yang diberikan adalah kacang tanah. Monyet-monyet muda memilih makanan yang lebih beragam daripada moyet dewasa. Monyet-monyet muda ini juga minum nira kelapa dari bumbung yang digantung di pohon kelapa di sekitar Taman Kera. Monyet-monyet di taman kera ini bersifat omnivora. Mereka mengkonsumsi berbagai jenis makanan yang ada di tempat ini.

Party size yang yang dibentuk pada saat makan setiap jenis makanan oleh monyet-monyet ekor panjang di Taman Kera beragam. Strategi ini bertujuan untuk mengurangi perilaku agonistik antar individu Hal ini sangat penting untuk menjaga keutuhan kelompoknya.

FEEDING ECOLOGY OF LONG-TAILED MACAQUES

AT CIKAKAK MONKEY PARK

By Islamul Hadi

A THESIS

Submitted to the Bogor Agricultural University

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Master Degree of Biology

GRADUATE SCHOOL

BOGOR AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY BOGOR

This is to certify that the thesis

Title : Feeding Ecology of Long-tailed Macaques at Cikakak Monkey Park

Name : Islamul Hadi

Student Number : G425010181 Study Program/Sub : Biology/Zoology

has been accepted toward fulfillment of the requirements for Master degree in Biology

1.Committee members

Dr. Bambang Suryobroto Dr. Ir. R. R. Dyah Perwitasari, M. Sc. Chairman Member

2.

Head of Study Program 3. Dean of Graduate SchoolDr. Ir. Dedy Duryadi S

, DEA Prof. Dr. Ir. Sjafrida Manuwoto, M. Sc

BIOGRAPHY

FOREWORD

This thesis entitled ” Feeding of Long-tailed Macaques at Cikakak Monkey Park”

based on the result of field research during September-November 2003 and March-April 2004. This research, globally, is aimed to collect information of presence of the living primates in Java, as the part of Primate Study in Java.

I wish to extend my gratitude to Dr. Bambang Suryobroto and Dr. R.R. Dyah Perwitasari, M. Sc. as the committee members. I wish to thanks to Mr. Bambang Juhari, Cikakak Monkey Park's caretaker. I am indebted to Prof. Dr. Kunio Wata-nabe and Dr. Sachiko Hayakawa from Primate Research Institute Kyoto University for their advices of methodology and discussions during field work and writing of the manuscript. I am also indebted to Mr. Jatiwan and his family for all their assistances and accommodation during field work.

Bogor, November 2005

LIST OF FIGURES

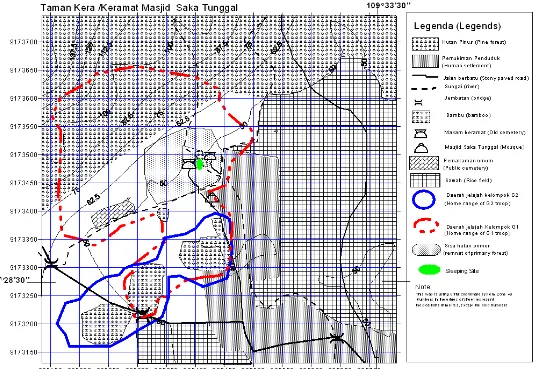

Page 1. Figure 1 Research location...…..………..…..9 2. Figure 2 Home ranges of troops of long-tailed macaques G1 and G2

FEEDING ECOLOGY OF LONG-TAILED MACAQUES

AT CIKAKAK MONKEY PARK

ISLAMUL HADI

GRADUATE SCHOOL

BOGOR AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY

BOGOR

STATEMENT OF RESEARCH ORIGINALITY

This is to verify that the thesis entitled :

Feeding Ecology of Long-tailed Macaques at Cikakak Monkey Park

Is my own work which has never previously been published. All of the incorporated data and information are valid and stated clearly

Bogor, 28 November 2005

ABSTRACT

ISLAMUL HADI. Feeding Ecology of Long-tailed Macaques at Cikakak Monkey Park. Under supervision of BAMBANG SURYOBROTO and R. R. DYAH PERWITASARI.

Long-tailed macaques in Cikakak Monkey Park obtain their food both from natural and human sources. They were recorded to consume 41 food items. Analysis using variables party size on foraging and feeding duration showed proportion of natural foods is greater than artificial foods. The averages were 76,39% and 23,61%, respectively. Based on the part eaten of natural foods, troop of macaques in this park consumed almost on young leaves and fruits. They consume and spend much time on young leaves of bamboo (Gigantochloa apus) and fruits from bulu (Ficus virens) and sadang (Corypha elatta). They also obtain food by raiding the crops from agricultural fields those surround the park. Insects were also consumed by them. The visitors and the caretakers of the park gave food, mainly peanuts. Juveniles and sub-adults of long-tailed macaques in this park exploited more various food items than those adults. They also drunk nira (raw coconut sap) from harvesting tubes in coconut trees. Therefore, they were regarded as omnivorous since they can exploit various kinds of food that available in time. ..

ABSTRAK

ISLAMUL HADI. Ekologi Makan Monyet Ekor Panjang di Taman Kera Cikakak. Dibimbing oleh BAMBANG SURYOBROTO dan R.R. DYAH PERWITASARI.

Monyet ekor panjang di Taman Kera Cikakak memperoleh makanan dari alam dan pengunjung sebanyak 41 jenis. Berdasarkan jumlah individu (party size) dan durasi makan, proporsi makanan dari alam lebih besar daripada yang diberikan oleh pengunjung. Proporsi ini masing-masing 76,39% dan 23,61%. Berdasarkan bagian yang dimakan pada makanan dari alam, monyet ekor panjang di tempat ini lebih banyak mengkonsumsi daun muda bambu ( Gigantochloa apus), buah jerakah bulu ( Ficus virens) dan sadang (Corypha elatta). Selain dari wilayah Taman Kera Cikakak, mereka juga mendapatkan makanan dari sawah dan kebun masyarakat Cikakak di sekitar taman. Monyet-monyet di sini juga mendapatkan makanan dari pengunjung dan penjaga makam. Makanan utama yang diberikan adalah kacang tanah. Monyet-monyet muda memilih makanan yang lebih beragam daripada moyet dewasa. Monyet-monyet muda ini juga minum nira kelapa dari bumbung yang digantung di pohon kelapa di sekitar Taman Kera. Monyet-monyet di taman kera ini bersifat omnivora. Mereka mengkonsumsi berbagai jenis makanan yang ada di tempat ini.

Party size yang yang dibentuk pada saat makan setiap jenis makanan oleh monyet-monyet ekor panjang di Taman Kera beragam. Strategi ini bertujuan untuk mengurangi perilaku agonistik antar individu Hal ini sangat penting untuk menjaga keutuhan kelompoknya.

FEEDING ECOLOGY OF LONG-TAILED MACAQUES

AT CIKAKAK MONKEY PARK

By Islamul Hadi

A THESIS

Submitted to the Bogor Agricultural University

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Master Degree of Biology

GRADUATE SCHOOL

BOGOR AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY BOGOR

This is to certify that the thesis

Title : Feeding Ecology of Long-tailed Macaques at Cikakak Monkey Park

Name : Islamul Hadi

Student Number : G425010181 Study Program/Sub : Biology/Zoology

has been accepted toward fulfillment of the requirements for Master degree in Biology

1.Committee members

Dr. Bambang Suryobroto Dr. Ir. R. R. Dyah Perwitasari, M. Sc. Chairman Member

2.

Head of Study Program 3. Dean of Graduate SchoolDr. Ir. Dedy Duryadi S

, DEA Prof. Dr. Ir. Sjafrida Manuwoto, M. Sc

BIOGRAPHY

FOREWORD

This thesis entitled ” Feeding of Long-tailed Macaques at Cikakak Monkey Park”

based on the result of field research during September-November 2003 and March-April 2004. This research, globally, is aimed to collect information of presence of the living primates in Java, as the part of Primate Study in Java.

I wish to extend my gratitude to Dr. Bambang Suryobroto and Dr. R.R. Dyah Perwitasari, M. Sc. as the committee members. I wish to thanks to Mr. Bambang Juhari, Cikakak Monkey Park's caretaker. I am indebted to Prof. Dr. Kunio Wata-nabe and Dr. Sachiko Hayakawa from Primate Research Institute Kyoto University for their advices of methodology and discussions during field work and writing of the manuscript. I am also indebted to Mr. Jatiwan and his family for all their assistances and accommodation during field work.

Bogor, November 2005

LIST OF FIGURES

Page 1. Figure 1 Research location...…..………..…..9 2. Figure 2 Home ranges of troops of long-tailed macaques G1 and G2

LIST OF TABLES

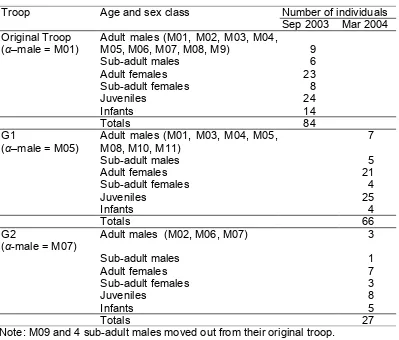

Page 1. Table 1 Composition of troop of long-tailed macaque in Cikakak……….……….…7

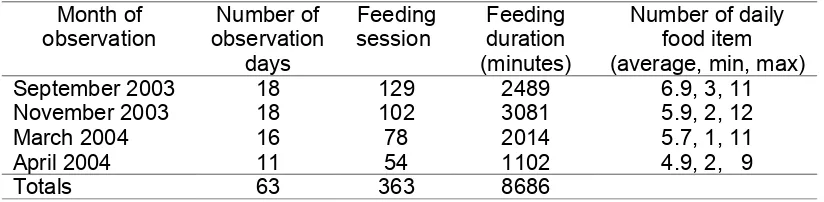

2. Table 2 Details of feeding duration and feeding sessions………....……...11

3. Table 3 List of natural food items were eaten by long-tailed macaque in

Cikakak Monkey Park...………...12

4. Table 4 List of artificial food items were eaten by long-tailed macaque in

Cikakak Monkey Park...……….……..13

5. Table 5 Part eaten of natural food by long-tailed macaques in

LIST OF APPENDIXES

Page 1. Appendix 1 List of vernacular names of natural food items of long-tailed

macaques in Cikakak Monkey Park...21 2. Appendix 2. Number of individual and time spent in each food item

by long-tailed -macaques in Cikakak Monkey Park...22 2. Appendix 3 Spatial distribution of fig trees ( Ficus spp)

in Cikakak Monkey Park...23 3. Appendix 4 Spatial distribution of langkap ( Arenga obtusifolia)

in Cikakak Monkey Park...24 4. Appendix 5 Spatial distribution of sadang (Corypha elatta)

in Cikakak Monkey Park...25 5. Appendix 6 Spatial distribution of grazing area in Cikakak Monkey Park...26 6. Appendix 7 Spatial distribution of bambu/bamboo (Gigantochloa apus)

INTRODUCTION

Background

The long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis) has wide geographic distribution ranging from southernmost Bangladesh to continent of Southeast Asia, Malayan Peninsula, Nicobar Islands, Sunda Archipelago, and the Philippines, except Sulawesi Island (Napier & Napier 1967; Fooden 1995). They are also found in Lesser Sunda Archipelago (Lombok, Sumbawa, and Timor), Kabaena Island, Angaur Island, and Mauritius and were suspected as introduced animals (Fooden 1991; Kawamoto et al. 1988; Kondo et al. 1993; Matsubayashi et al. 1992).

They adapt to various environments from mangrove swamp (Hock & Sase-kumar 1979), lowland-dense-tropical and sub-alpine forests, and also to the communal places where humans live. These facts indicate that they have a great ecological plasticity to adapt to various environments; therefore, they are regarded as “weed” species (Richard et al. 1989).

Following recent economic development in Java, most of primary forests where long-tailed macaques live were converted for land of buildings, factories, farming fields, secondary forests, recreation parks, and human settlements. The impacts are decreasing area of primary and secondary forests.

Some remnant populations of long-tailed macaques in Java have been recorded. They were found in Plangon, Jatibarang, Kalijaga, Solear, Pangandaran, Cikakak, Tawangmangu and Cepu (Hadi 2001; Hasanbahri et al. 1996; Perwitasari-Farajallah 1998; Hadi, present study). They live in secondary forests and some of them in monkey parks. Almost all of populations are separated from each other following their fragmented habitats. Population of long-tailed macaques in Pangandaran separated from those in Cikakak, Plangon, Kalijaga, and Solear, vice versa. No corridors for their contact. Perwitasari-Farajallah (1998) reported that genetically they have high variation among but low within the population. Kawamoto et al. (1981) reported that population of long-tailed macaques in Jatibarang had low-level genetic variability presumably caused by their isolation from other populations.

with human tend to be frugivorous (Yeager 1996). They are organized in small sized groups with large home ranges. In the area with high frequencies of contact with human beings, the macaques tend to be omnivorous. Their main dietary items are not only fruits. They exploit other kinds of food such as flowers, leaves, seeds, insects, and tubers. They also get food from human. They are organized into big sized groups with small home ranges and higher reproduction index (Aggimarangsee 1992; Hadi 2001; Wheatley 1984). Almost all of the troops live in small areas with decreasing space for searching foods. It is suspected that they face high individual competition for resources and risk increasing on inbreeding. The data of feeding ecology of long-tailed macaques in Java are insufficient since no intensive research had been carried out on this species. In this research, the quantitative approach in feeding ecology is applied to describe the feeding ecology of long-tailed macaque population lives in a place with high frequencies of contact with human being.

Objective of Research

LITERATURE STUDY

Systematic of Long-tailed Macaque

According to Grove (2001), long-tailed macaque belongs to : Order : Primates

Based on the morphology of reproductive organs, Fooden (1980) classified long-tailed macaques to fascicularis species group. Another members of this group are Japanese macaques (M. fuscata), rhesus macaques (M. mulatta) and Formosan macaques (M. cyclopis).

Geographic Distribution

Long-tailed macaque has wide geographical range. They distribute in southernmost Bangladesh, Nicobar Island, Indochinese Peninsula, Isthmus of Kra, Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Borneo, Java, and Philippine (Fooden 1995; Umapathy et al.

2003). They are also found in Lesser Sunda (from Lombok to East Timor; Kawamoto

et al. 1984) and suspected as introduced animal. Long-tailed macaque also introduced by human to Mauritius Island, Angaur Island, Kabaena Island, and Tinjil Island (Kawamoto et al. 1988; Kondo et al. 1993; Kyes 1993; Matsubayashi et al.

1992; Perwitasari-Farajallah 2004).

Socioecology

According to Fooden (1995), long-tailed macaque’s home ranges vary among territories and conditions. In Simeuleu, North Sumatra, the average home ranges were 12.5 Ha and in West Malaysia was noted as around 300 Ha. The width of home ranges were affected by number of individuals in the troop and availability of food resources.

Troop size of long-tailed macaques also vary among places and conditions. Fooden (1995) reported troop size in non-provisioned areas were 12-25 individuals. In provisioned troops they exceeded the average size of non-provisioned ones (e.g. Cikakak, 46.3 individuals, n = 2 troops, present study).

Long-tailed macaques have plasticity to live with other primate species. In Sumatra, they live simpatrically with pig-tailed macaques, M. nemestrina (Crocket & Wilson 1980). Wheatley (1980) reported long-tailed macaques in East Borneo live simpatrically with orang utan (Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus). They were also found to live with ebony leaf-eater monkeys (Trachypithecus auratus) in Java and Lombok Island (Hadi, unpublished data). Hock & Sasekumar (1979) also reported long-tailed macaques were found to live simpatrically with silvered-leaf monkey (Presbytis cristata) in Kuala Selangor, Malay Peninsula. In Ketambe forests in Sumatera, long-tailed macaques live with Thomas langur (P. thomasii) and orang utan (Pongo abelii). Even though they live simpatrically, those species of primates separated their niches to avoid competition for food resources.

Reproduction

Individuals of long-tailed macaque reach their sexual maturity in age 5-6 years old for males and 4 years old for females (Varavudhi et al. 1992). These adult females give their first birth in age 4 years.

Feeding Ecology of Long-tailed Macaques

these macaques consumed fruits from 24 species of plants. In the teak forest at Cepu, Hasanbahri (1996) recorded 33 species of plants were consumed by long-tailed macaques and fruits were the most preferable to be chosen as the food.

Due to disturbance of habitat and intensive contact with human long-tailed macaques change their feeding behavior. They exploit any available food resources and these make them omnivorous (Wheatley 1989). These provisioned troops can be found in the recreation areas, temples and cemeteries (Aggima-rangsee1992; Hadi 2001). Long-tailed macaques were noted to share food resources with other species as the consequent of their living in simpatry. In Malaysia, these macaques share fig fruits with dusky langur (Presbytis obscura), some gibbons (Hylobates spp.) (Lambert 1990), silvered-leaf monkey, Presbytis cristata (Hock & Sasekumar 1979).

Data on feeding ecology of long-tailed macaques are scarce, especially in Java, compared to other species. Most data of feeding ecology in genus Macaca comes from Japanese macaque in some regions. Hanya (2003) reported age differences of food intake and dietary selection in the wild male Japanese macaques. Juveniles tend to feed on animal matters than adult males and avoid to consume high-fibrous food. However, time spent for food of those two age-stages were not different. Inter-regional, inter-seasonal, and altitudinal variation of food choices in this species had also been studied (Hanya et al 2003; Nakagawa et al. 1996). Data of feeding ecology in Formosan rock macaques (M. cyclopis) had also been reported (Su & Lee 2001).

METHODS

Research Site

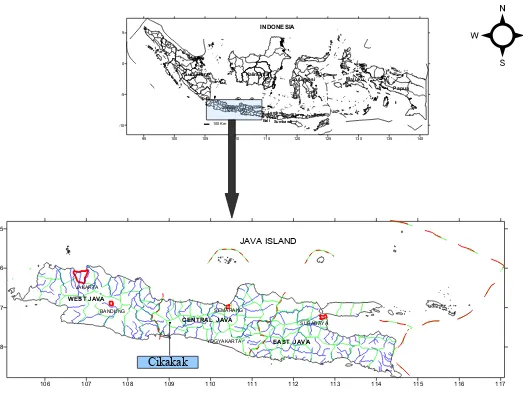

This research was conducted in Cikakak Monkey Park, a part of Sub-district Wangon, District of Banyumas, Central Java Province (Figure 1). The central study area lies on 9173400 mN to 9173550 mN and 285300 mE to 285450 mE, UTM coordinate system zone 48, based on map from National Coordinating Agency for Surveys and Mapping (BAKOSURTANAL). This site is a remnant of primary forest that is surrounded by human settlement, farming fields, and pine forest. The forest is under the authority of Perum Perhutani Division I Central Java, a subsidiary forestry company under Ministry of Forestry. The area is a special purpose area (LDTI = lahan dengan tujuan istimewa) for conservation of long-tailed macaques and cultural heritage consisting of old cemetery called keramat and old mosque called Masjid Saka Tunggal (meaning single pole mosque) that were built in 1522 AD. This area partly used by people to cultivate crops.

The research site encompassed 4.2 ha LDTI's area with altitude 30-125 m above sea level and annual rainfall 2810 mm. The highest rainfall occurs during mid November to mid December.

Subject

Table 1 Composition of troop of long-tailed macaque in Cikakak Monkey Park

Troop Age and sex class Number of individuals

Sep 2003 Mar 2004 Original Troop

(α–male = M01)

Adult males (M01, M02, M03, M04,

M05, M06, M07, M08, M9) 9

Adult males (M01, M03, M04, M05, M08, M10, M11)

Note: M09 and 4 sub-adult males moved out from their original troop. During observation 5 infants were born and one of them was died

Data Collection Method and Period

Data was collected during September-November 2003 and February-April 2004, (September = 18 days, November = 18, March = 16 days, April = 11 days).

Feeding session is foraging activity of the troop in a food patch at a certain time. A food patch is roughly equivalent with a food item. During a feeding session, the number of individuals who fed on the food and also the duration of eating the food were recorded. Recording the duration of feeding started when the first individuals enter to the food patch and started to manipulate manually and orally part of food item. The recording terminated when the last individuals stopped to feed and/or leave feeding site. Data collection was obtained from 07:00-12:00 am and 02:00-05:30 pm. Observation was terminated when the rain started.

Data Analysis

When forage for food, instead of all individuals enter a food patch, the troop formed a party. The individuals who formed a party in foraging on a certain food item i (i=1 to k) are shifted and overlapped among sessions. The maximum number of individuals who forage in one feeding session x (x = 1 to m) is defined as nix party

size. Therefore, to represent the troop, present analysis takes the average of party size on food item i (Ni)

Since the availabilities among foods are asynchronous, the duration of availability of food, and preference the macaques to the food is unequal, it was considered to use cumulative of duration for the data analysis.

95 100 105 110 115 120 125 130 135 140

106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117

Figure 2 Home ranges of troops of long-tailed macaques G1 and G2 in Cikakak Monkey Park

RESULTS

Observation on the troop of long-tailed macaque in Cikakak Monkey Park revealed 8686 minutes of feeding duration in 363 feeding sessions (table 2).

Table 2 Details of feeding duration and feeding sessions Month of

September 2003 18 129 2489 6.9, 3, 11

November 2003 18 102 3081 5.9, 2, 12

March 2004 16 78 2014 5.7, 1, 11

April 2004 11 54 1102 4.9, 2, 9

Totals 63 363 8686

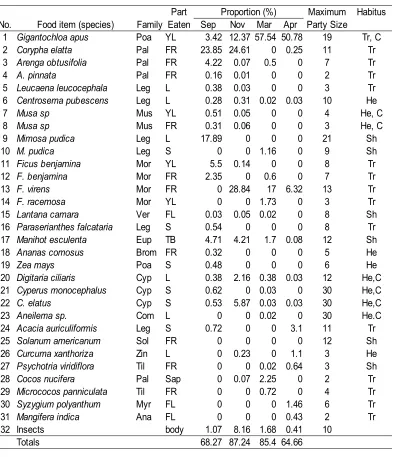

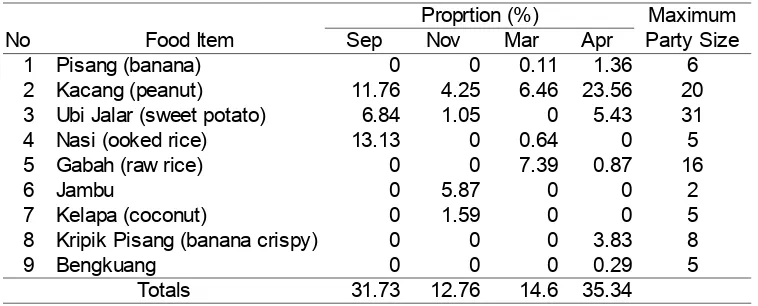

They were observed to feed on 32 natural and 9 artificial food items (tables 3 and 4). The items obtained from natural resources were furthermore categorized based on part eaten (fruits, leaves, seeds, flowers, tuber, nira (raw coconut sap) and insects) (table 5). Artificial food items were provided by caretakers of the mosque and tourists who visit this area. In total, the troop obtained 76.39% food from natural sources and 23.61% from human.

Proportion of food part eaten were different significantly each month (df = 6,

p<0.01, X2 for September = 117.32, November = 171.48, March = 236.74, April =

234.49). Proportion of leaves and fruits eaten were not different significantly (t0.05 (2), 6 = 0,47 n1 = 4, n2 = 4). Between source of food, natural source and human source also differ significantly each month (df = 1, p =0.05, X2 for September = 13.3,

November = 56.49, March = 56.73, April = 172.45).

Table 3 List of natural food items were eaten by long-tailed macaque in Cikakak Monkey Park

Notes : Ana = Anacardiaceae Poa = Poaceae/Gramineae, Pal = Palmae /Areca-ceae, Leg = Legumino/Areca-ceae, Mus = Musa/Areca-ceae, Mor = Mora/Areca-ceae, Eup = Euphorbiaceae, Brom = Bromeliaceae, Ver = Verbenaceae, Cyp = Cyperaceae, Com = Commelinaceae, Zin = Zingiberaceae, Myr = Myrtaceae, Til = Tiliaceae, Sol = Solanaceae, YL = young leaf, L = leaf, F = fruit, S = seed, FL = flower, N = Nira (raw coconut sap), B = body, C = clump, Tr = Tree, He = Herb, Sh= shrub, Sep = September 2003, Nov = November 2003, Mar = March 2004, Apr = April 2004

No. Food item (species) Family

Part Proportion (%) Maximum Habitus Eaten Sep Nov Mar Apr Party Size

1 Gigantochloa apus Poa YL 3.42 12.37 57.54 50.78 19 Tr, C 2 Corypha elatta Pal FR 23.85 24.61 0 0.25 11 Tr 3 Arenga obtusifolia Pal FR 4.22 0.07 0.5 0 7 Tr 4 A. pinnata Pal FR 0.16 0.01 0 0 2 Tr 5 Leucaena leucocephala Leg L 0.38 0.03 0 0 3 Tr 6 Centrosema pubescens Leg L 0.28 0.31 0.02 0.03 10 He

7 Musa sp Mus YL 0.51 0.05 0 0 4 He, C 16 Paraserianthes falcataria Leg S 0.54 0 0 0 8 Tr 17 Manihot esculenta Eup TB 4.71 4.21 1.7 0.08 12 Sh 18 Ananas comosus Brom FR 0.32 0 0 0 5 He

19 Zea mays Poa S 0.48 0 0 0 6 He

20 Digitaria ciliaris Cyp L 0.38 2.16 0.38 0.03 12 He,C 21 Cyperus monocephalus Cyp S 0.62 0 0.03 0 30 He,C 22 C. elatus Cyp S 0.53 5.87 0.03 0.03 30 He,C 23 Aneilema sp. Com L 0 0 0.02 0 30 He.C 24 Acacia auriculiformis Leg S 0.72 0 0 3.1 11 Tr 25 Solanum americanum Sol FR 0 0 0 0 12 Sh 26 Curcuma xanthoriza Zin L 0 0.23 0 1.1 3 He 27 Psychotria viridiflora Til FR 0 0 0.02 0.64 3 Sh 28 Cocos nucifera Pal Sap 0 0.07 2.25 0 2 Tr 29 Micrococos panniculata Til FR 0 0 0.72 0 4 Tr 30 Syzygium polyanthum Myr FL 0 0 0 1.46 6 Tr 31 Mangifera indica Ana FL 0 0 0 0.43 2 Tr 32 Insects body 1.07 8.16 1.68 0.41 10

Table 4 List of artificial food items were eaten by long-tailed macaque in Cikakak Monkey Park

Table 5 Part eaten of natural food by long-tailed macaques in Cikakak Monkey Park

Some individuals of the troops of long-tailed macaque were recorded to eat insects. They obtained it manually from the leaves and flowers. They grabbed leaves where the insects were seen. In this study, two species of trees, salam (S. polyanta) and matoa (Pometia sp.) were the sources of insects. They were observed to catch insects who pollinated flowers of matoa and salam. Long-tailed macaques obtained grasshoppers from grazing area. Another method used by some sub-adult males was moving stones by hand to search for termites and soil arthropods. They also consumed some caterpillars from leaves of coconut trees and salam.

Crop raiding by long-tailed macaques was recorded in Cikakak. This activity 2 Kacang (peanut) 11.76 4.25 6.46 23.56 20 3 Ubi Jalar (sweet potato) 6.84 1.05 0 5.43 31 4 Nasi (ooked rice) 13.13 0 0.64 0 5 5 Gabah (raw rice) 0 0 7.39 0.87 16

6 Jambu 0 5.87 0 0 2

7 Kelapa (coconut) 0 1.59 0 0 5 8 Kripik Pisang (banana crispy) 0 0 0 3.83 8

9 Bengkuang 0 0 0 0.29 5

Totals 31.73 12.76 14.6 35.34

No. Part eaten

Proportion (%) Average Sep Nov Mar Apr

DISCUSSION

There were variation on the feeding duration and number of individuals during foraging. Hadi (2001) reported those sub-adult of long-tailed macaques in Pangandaran showed variation in frequencies of foraging on each food item. Some individuals ate a food while others did not. During foraging, long-tailed macaques in Cikakak Monkey Park formed smaller subgroups. The fact is equivalent to those proposed by Read (1987). The number of individuals varied among periods and food items. The subgroups were formed probably based on social bonding. Present report focus on how subgroup, which represent troop, forage food items.

Foraging activities of the troop was determined by food patch characteristics, that is, type or habitus (tree, shrub, herb), spreading of food in grass field and abundance of the food item The food patch restricted the maximum number of individuals (party size) to forage. Other members of the troop waited until some individuals in the patch stopped to forage and/or foraged on the different item in the park. The restricted party size seemed to minimize agonistics among individuals during foraging.

Troop of long-tailed macaques in Cikakak obtain their food from resources in their habitat rather than from human resources. Even though this place is one of the popular recreation areas in Banyumas, where many peoples come and give food to the macaques, the proportion of food they take is much smaller than from their habitat. In other word, the troop of long-tailed macaques in Cikakak were not depended on the presence of human beings. It was in contrast with the long-tailed macaques live in other recreation areas. In Pangandaran Recreation Park, long-tailed macaques spend their time to feed on the offering from human up to 52% from total of their diet time (Hadi 2001). In temple of Ubud, Bali, long-tailed macaque also obtain food from human up to 58% of their dietary proportion (Wheatley 1989).

During the study, two species of trees provide fruits with high preference to long-tailed macaque. They are sadang (C. elatta : Arecaceae/Palmae) and jerakah bulu (F. virens : Moraceae). The first fruit was available from July to November and the second species available from November to July. Even though this area is poor for fruit trees, long-tailed macaque can obtain fruit continuously along the year from those two species. Hasanbahri et al. (1996) reported in teak forest, which was noted to be poor for fruit trees since the forest was mono cultural type, dietary of long-tailed macaques was also dominated by fruits from fig trees (Ficus spp.)

CONCLUSION

Long-tailed macaques in Cikakak obtain their food both from natural and human sources. They were recorded to consume 41 food items. Proportion of food from natural resources is greater than those from human sources. They consumed and spent much time on young leaves of bamboo (Gigantochloa apus) and fruits from jerakah bulu (F. virens) and palm trees (Corypha elatta) . They also obtain food, mainly peanut, from visitor of the park. In the other word, long-tailed macaques in this park were omnivorous. They exploited various kinds of food resource that available in time.

REFERENCES

Aggimarangsee N. 1992. Survey for semi-tame colonies of macaques in Thailand.

Nat Hist Bul Siam Soc 40: 103-166.

Boer L, Sosef MSM. 1998. Ficus L. In : Sosef MSM, Hong LT, Prawirohartono S, editors. Plant Resources of South-East Asia 5(3). Timber Tress : Lesser Known Timber. Leiden : Brackhuys Publication.

Backer CA, van den Brink RCB. 1965. Flora of Java. Volume II. Groningen : NVP Noordhoff.

Crocket CM, Wilson WL. 1980. The ecology sparation of Macaca nemestrina and

M.fascicularis in Sumatera. ). In: Lindburg DE, editor. The Macaques: Study in Ecology, Behaviour, and Evolution. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

Das PK, Ghosal DK. 1977. Notes on the Nicobar crab-eating macaque. News Zool Surv India 3 : 264-267.

Feitzel JK, Chen CP.1992. Centrosema pubescens Benth. In : 't Mannetje L, Jones RM, editors. Plant Resources of South-East Asia 4. Foragers.Bogor : Prosea.

Fittinghoff NA, Lindburg DG. 1980. Riverine refuging in east Bornean Macaca fascicularis. In: Lindburg DE, editor. The Macaques: Study in Ecology, Behaviour, and Evolution. New York : Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

Fleagle JF. 1988. Primate Adaptation and Evolution. London : Academic Press Inc.

Fooden J. 1980. Classification and distribution of living macaque (Macaca lacepede, 1799). In: Lindburg DE (ed) The Macaques: Study in Ecology, Behaviour, and Evolution. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

Fooden J. 1991. New perspectives on macaque evolution. In : Primatology Today. Ehara A, Kimura T, Takenaka O, Iwamoto M, editors. Amsterdam:Elsevier Science Publisher.

Fooden J. 1995. Sytematics review of Southeast Asian Longtail Macaques, Macaca fascicularis (Raffles [1821]). Fieldiana : Zoology 81: 1-270

Grove CP. 2001. Primate Taxonomy. Washington:Smithsonian Institute Press.

Hadi I. 2001. Pemilihan makanan oleh monyet karier butawarna [minithesis]. In Indonesian, abstract in English. Bogor Agricultural University.

Hadi I. 2005. Distribution and present status of long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in Lombok Island, Indonesia.The Nat Hist J Chula Univ 2005, Supl 1 : 90

Hanya G, Noma N, Agetsuma N. 2003. Altitudinal and seasonal variation in the diet of Japanese macaques in Yakushima. Primates 44: 51-59.

Hasanbahri S, Djuwantoko, Ngariana IN. 1996. Komposisi jenis tumbuhan pakan kera ekor panjang (Macaca fascicularis) di habitat hutan jati. Abstract in English.

Biota 1(2): 1-8.

Hock LB, Sasekumar A. 1979. A preliminary study on the feeding biology of mangrove forest primates, Kuala Selangor. The Malay Nat J 33: 105-113.

Janson CH, van Schaik CP. 1993. Ecological risk aversion in juvenile primates : slow and steady wins the race. In : Pereira ME, Fairbanks LA (eds). Juvenile Primates. New York : Oxford University Press.

Jones R, Brewbacker JL, sorensson CT. 1992. Lucaena leucocephala (Lamk) Width. In 't Mannetje L, Jones RM, editors. Plant Resources of South-East Asia 4. Foragers. Bogor : Prosea.

Kawamoto Y et al. 1981. Genetic variability and differentiation of local population in the Indonesian crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis). Kyoto Univ Overseas Res Rep Stud Indonesian Macaque 1 : 15-39

Kawamoto Y et al. 1988. A population-genetic study of crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis) on the island of Angaur, Palau, Micronesia. Folia Primatol

1: 169-181.

Kondo et al. 1993. A population-genetic study of crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis) on the island on the Island of Mauritius. Am J Primatol 29:167-182.

Kyes RC. 1993. Survey of the long-tailed macaques introduced onto Tinjil Island, Indonesia. Am J Primatol 31:77-83.

Lambert F.1990. Some notes on fig-eating by arboreal mammals in Malaysia.

Napier JR, Napier PH. 1967. A Handbook of Living Primates. New York: Academic Press.

Kyoto University.

Perwitasari-Farajallah D. 2004. Genetic variability in the population of long-tailed macaques introduced into Tinjil Island, Indonesia: microsatellite loci variation.

Hayati 11 : 21-24.

Read DW. 1987. Foraging society organization: a simple model of complex transition. Euro J Oper Res. 30 : 230-236

Richard AF, Goldstein SJ, Dewar RE. 1989. Weed macaques: the evolutionary implications of macaque feeding ecology. Int J Primatol 10: 569-294.

Sudarnadi H. 1996. Tumbuhan Monokotil. Jakarta: Penebar Swadaya.

Su H, Lee L. 2001. Food habit of Formosan rock macaques (Macaca cyclopsis) in Jentse, Northeastern Taiwan, assesed by fecal analysis and behavioral observation. Int J Primatol 22: 359-377.

Umapathy G, Singh M, Mohnot SM. 2003. Status and distribution of Macaca fascicularis umbrosa in The Nicobar Island, India. Int J Primatol 24: 281-292.

Ungar PS. 1994. Patterns of ingestive behavior and anterior tooth use in sympatric anthropoid primates. Am. J Phys Anth 95: 197-219.

Varavudhi P, Suwanpraset K, Settheetham W.1992. Reproductive endocrinology of free-ranging adult cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). In : Matan S, Tuttle HR, Ishida H, Gordon M, editors. Topics in Primatology . Volume 3. Tokyo : Tokyo University Press.

Wee YC, Thongtham MLC. Ananas comosus. In:Verheij EWM, Coronel REC, editors. Plant Resources of South-East Asia 2. Edible Fruit and Nuts. Bogor : Prosea.

Wheatly BP. 1980. Feeding and ranging of East Bornean Macaca fascicularis. In: Lindburg DE, editor. The Macaques: Study in Ecology, Behaviour, and Evolution. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company

Wheatly BP. 1989. Diet of Balinese temple monkeys, Macaca fascicularis. Kyoto Univ Overseas Res Rep Stud Asian non-Human Primates 7: 62-75

Appendix 1 List of vernacular names of natural food items of long-tailed

1 Gigantochloa apus bambu tali Poaceae Tr, C 2 Corypha elatta sadang Palmae/Arecaceae Tr 3 Arenga obtusifolia langkap Palmae/Arecaceae Tr 4 Arenga pinnata kawung Palmae/Arecaceae Tr 5 Leucaena leucocephala kemlandingan Leguminoceae Tr 6 Centrosema pubescens bunga kupu-kupu Leguminoceae He

7 Musa sp pisang Musaceae He, C

8 Musa sp pisang Musaceae He, C

9 Mimosa pudica putri malu Leguminoceae Sh 10 Mimosa pudica putri malu Leguminoceae Sh 11 Ficus benjamina beringin Moraceae Tr 12 Ficus benjamina beringin Moraceae Tr

13 Ficus virens bulu Moraceae Tr

14 Ficus racemosa lo Moraceae Tr

Appendix 2 Number of individual and feeding duration in each food item by tailed macaques in Cikakak Monkey Park

Ni = Average party sizes (individuals), Ti = feeding duration (minutes) No. Food item

Sep Nov Mar Apr Ni Ti Ni Ti Ni Ti Ni Ti 1 Gigantochloa apus 6,33 170 15,41 349 18,64 960 20,7 439 2 Corypha elatta 9,87 759 13 823 0 0 5 9 3 Arenga obtusifolia 6,64 200 3 10 3,67 42 0 0

4 Arenga pinnata 2 25 1 5 0 0 0 0

16 Paraserianthes falcataria 8,5 20 0 0 0 0 0 0 17 Manihot esculenta 13,83 107 30,5 60 12 44 1,5 10

18 Ananas comosus 5 20 0 0 0 0 0 0

19 Zea mays 6 25 0 0 0 0 0 0

20 Digitaria ciliaris 4 30 13,4 70 3,37 35 1 5

21 Cyperus monocephalus 7 28 2 5 0 0

22 Cyperus elatus 12 14 23,2 110 2 5 1 5

23 Aneilema sp. 0 0 0 0 1 5 0

24 Acacia auriculiformis 15 15 0 0 0 0 15 37

25 Solanum americanum 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

26 Curcuma xanthoriza 0 0 4 25 0 0 7 28 27 Psychotria viridiflora 0 0 0 0 1 5 2,5 46

28 Cocos nucifera 0 0 2 15 6 117 0 0

29 Micrococos panniculata 0 0 0 0 7,5 30 0 0 30 Syzygium polyanthum 0 0 0 0 0 0 5,67 46

31 Mangifera indica 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 13

=

Ficus racemosa (n = 3 trees)

=

Ficus virens (n = 3 trees)

=

Ficus benjamina (n = 2 trees)

285150 285200 285250 285300 285350 285400 285450 285500 285550 285600 285650 285700 9173150

9173200 9173250 9173300 9173350 9173400 9173450 9173500 9173550 9173600 9173650 9173700

Appendix 3 Spatial distribution of fig trees ( Ficus spp) in Cikakak Monkey Park

285150 285200 285250 285300 285350 285400 285450 285500 285550 285600 285650 285700 9173150

9173200 9173250 9173300 9173350 9173400 9173450 9173500 9173550 9173600 9173650 9173700

Appendix 4 Spatial distribution of langkap ( Arenga obtusifolia) in Cikakak Monkey Park

langkap (Arenga obtusifolia)

n = 90 trees in reproductive stages

Appendix 5 Spatial distribution of sadang (Corypha elatta) in Cikakak Monkey Park

=

sadang ( Corypha elatta) n = 56 treesiii

285150 285200 285250 285300 285350 285400 285450 285500 285550 285600 285650 285700 9173150

285150 285200 285250 285300 285350 285400 285450 285500 285550 285600 285650 285700 9173150

9173200 9173250 9173300 9173350 9173400 9173450 9173500 9173550 9173600 9173650 9173700

Grazing area - Digitaria ciliaris

- Cyperus monocephalus - Cyperus elatus

- Aneilema sp. - Mimosa pudica

- Centrosema pubescens

Appendix 7 Spatial distribution of bambu/bamboo (Gigantochloa apus) in Cikakak Monkey Park

285150 285200 285250 285300 285350 285400 285450 285500 285550 285600 285650 285700 9173150

9173200 9173250 9173300 9173350 9173400 9173450 9173500 9173550 9173600 9173650 9173700

bambu =Gigantochloa apus n = 40 clumps