Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:58

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Integrating Human Rights in Business Education:

Embracing the Social Dimension of Sustainability

Jennifer Palthe

To cite this article: Jennifer Palthe (2013) Integrating Human Rights in Business Education: Embracing the Social Dimension of Sustainability, Journal of Education for Business, 88:2, 117-124, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.648969

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.648969

Published online: 04 Dec 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 365

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.648969

Integrating Human Rights in Business Education:

Embracing the Social Dimension of Sustainability

Jennifer Palthe

Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA

In today’s complex global environment, business educators need to play a more strategic role in moving the business sector from a compliance orientation to one in which future business leaders are equipped to serve as strong advocates for human rights and every dimension of sustainability (environmental, economic, and social). While much innovative work is under-way to embed human rights in business, the author aims to provide business educators with resources to do likewise so that the emergence of a new generation of business leaders may be fostered—leaders who incorporate human rights into their decision making and serve as powerful influencers in establishing an inclusive and sustainable world.

Keywords: business education, human rights, social sustainability, sustainability

I think responsible leadership will shape business and soci-ety in a very constructive way if there is a recognition that respect for human rights is part of that responsible leader-ship and indeed part of business sustainability....In a world

so deeply divided between rich and poor, North and South, religious and secular, us and them, we need more than ever common values—a “common standard of achievement” as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights puts it.

—Mary Robinson, President of Realizing Rights: The Ethical Global Initiative, Former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and Former President of Ireland (2009)

Progressing through the second decade of a new century, there is a growing belief that organizations should engage in more deliberate strategies to achieve sustainable solutions to social and environmental challenges (Haugh & Talwar, 2010). The global economic recession and virtual collapse of the worldwide financial services industry has not only ex-posed the shortcomings in corporate financial risk manage-ment but has stimulated a greater awareness of the depen-dency of business success on generating sustainable worth (Audebrand, 2010). While there have been significant efforts to integrate sustainability in management education (Benn & Dunphy, 2009; Rusinko, 2010; Starik, Rands, Marcus, & Clark, 2010), the emphasis has been more on environmental

Correspondence should be sent to Jennifer Palthe, Western Michi-gan University, Haworth College of Business, Department of Manage-ment, 3220 Schneider Hall, Kalamazoo, MI 49008, USA. E-mail: jennifer. [email protected]

and economic sustainability (Bansal & Roth, 2000; Christ-mann, 2004; Porter & Cordoba, 2009), and business schools have been somewhat remiss in emphasizing the human issues associated with managing an organization than the economic issues (Giacalone & Thompson, 2006). Moreover, the full scope of sustainability has not yet become embedded in main-stream business education (Alcaraz & Thiruvattal, 2010) and human rights and the social dimension of sustainability has been given less attention than economic and environmental issues (Pfeffer, 2010).

At a United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) U.S. net-work meeting in 2008, Mike Toffel, Harvard Business School professor, argued: “The topic of human rights is new to busi-ness scholarship. Although there are peripheral mentions of human rights, there is still plenty of room for management knowledge and practice to work on the implementation of hu-man rights” (UNGC, 2008c, p. 1). In 2008, the 60th Anniver-sary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) provided a reminder that protecting human rights is a shared responsibility for governments and their citizens, and organi-zations and their employees around the world. Human rights are defined as the basic standards aimed at securing dignity and equality for all (UNGC, 2008a). The UDHR called on every organ of society to play its role in promoting human rights. When Eleanor Roosevelt addressed the UN General Assembly in Paris on December 10, 1948, she called on all to play their part:

Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home—so close and so small that they cannot

118 J. PALTHE

be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighborhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm, or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerted citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.

Humans and not just effective business are pivotal to both the long-term survival of corporations and the wealth of na-tions. Whether it is human rights to fair treatment, adequate health care, safety, equity, advancement, education, or equal representation, nothing can be mobilized and no sustainable progress can be achieved in the absence of genuine respect for this vital resource (Palthe, 2008). This is a monumen-tal time in history where the world is at a critical juncture (United Nations Development Program, 2010). With the hu-man population increasing more than 200,000 net each day, and the numbers of chronically hungry people in the world going up, not down, there are unprecedented global calami-ties to face (UNDP, 2010). Overcoming the global food crisis and energy crisis, reducing poverty, protecting the planet, and promoting peace critically depend on the ability to act collec-tively. The U.S. Gulf oil spill and disasters stemming from the earthquakes in Japan, Haiti, and Chile have given renewed impetus to the work of relief agencies, nongovernmental or-ganizaitons, and businesses engaged in helping to solve so-cietal and environmental crises worldwide. More businesses are forming alliances with nonprofit organizations (Murray, 2008) and there is clearly mounting pressure on businesses to be more actively involved in solving societal problems and to practice green management (Marcus & Fremeth, 2009). As the guest editors of the Academy of Management Learning and Educationargued in the recent special issue “In Search of Sustainability in Management Education,”

Neither the “business-as-usual” nor the incrementalist re-form approaches that most individuals, organizations, and societies have employed to address critical global sustain-ability issues is apparently enough to move us far enough fast enough to prevent near-term crises. (Starik et al., 2010, p. 377)

In light of this, business educators have a responsibility to equip business students with the knowledge and tools to manage in a increasingly complex world, and to explore the multifaceted (not simply economic) repercussions of their decisions (Pfeffer, 2010). Future business leaders need to understand the implications of these unprecedented global crises (UNDP, 2010) and to appreciate that promoting human rights is the responsibility of every organ of society (UNGC, 2008a). In this article I seek to draw attention to the im-portance of integrating human rights in business education, to embrace the often underrepresented social dimension of

sustainability. I review the present literature on sustainability and highlights some of the key global initiatives that integrate human rights and business. Recommendations and resources for reshaping business education through the incorporation of human rights are offered.

DIMENSIONS OF SUSTAINABILITY

Sustainability is a broad and evolving social construct (Collins & Kearins, 2010) and most definitions draw on the principles of the Brundtland Commission that defines sus-tainability as “meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987, p. 8). Others have defined sustain-ability as an effort to preserve resources and avoid waste in operations (Pfeffer, 2010). Sustainability is a systems-level concept that transcends national boundaries and embraces notions of equality, equity, and futurity (Collins & Kearins). There is a growing consensus that sustainability has three distinct yet interrelated dimensions: economic, environmen-tal, and social (Enkington, 1998; Haugh & Talwar, 2010). This three-part conceptualization provides a heuristic that business educators and students can use to understand the elements of sustainability more effectively. The environmen-tal dimension includes things such as waste management, preservation of animal and plant species, alternative energy production, improved emissions management, and efforts to recycle, reuse, and conserve (Rusinko, 2010). Economic sus-tainability considers things such as efforts to maintain organi-zational effectiveness, revenue generation, promotion of fair trade, and long-term survival and financial success of organi-zations. Examples of the social dimension include initiatives to promote diversity, protect human rights, reduce poverty, enhance workplace equity, and social justice (Rusinko). So-cial sustainability exemplifies the humanitarian context of business and also relates to human rights issues, income in-equality; disease, especially HIV/AIDS and malaria; access to clean water, sanitation, and health care; and education, especially for women (Haugh & Talwar).

The multidimensional conceptualization of sustainability not only provides a helpful framework for understanding sustainability but the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO; 2004) insisted that sustainability education must address all three dimensions (economic, environmental, and social) so that students de-velop the necessary knowledge, understanding and skills to foster improvements in all three areas. The UN Millennium Development Goals, also stipulated the need to address all three pillars of sustainability (United Nations, 2006). With these three dimensions in mind and the clear underrep-resentation of social sustainability, some of the key global initiatives that serve to integrate human rights in business education are highlighted next.

INTEGRATING HUMAN RIGHTS IN BUSINESS EDUCATION

A growing appreciation for the role of business taking on greater human rights responsibilities is occurring worldwide (United Nations, 2006). There are increasing numbers of nonprofit organizations, associations, and learning networks focused on sustainability and human rights. Some of these include the Association of Sustainability in Higher Educa-tion; the UNGC; UNESCO; the Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME); the World Resources In-stitute; the Aspen Institute (AI) Initiative for Social Inno-vation through Business; the Association to Advance Col-legiate Schools of Business (AACSB) Ethics/Sustainability Resource Center; and the Academy of Management. The sheer expansiveness and growth of these organizations is re-flective of the increasing recognition of the importance of integrating sustainability in business education.

One of the most notable initiatives that seeks to cham-pion the integration of sustainability in business education and that explicitly emphasizes human rights is the UNGC. The UNGC, a voluntary, CEO-led corporate sustainability initiative has over 5,000 participants in more than 130 coun-tries (Principles for Responsible Management, 2008). The UNGC offers a strategic policy framework and set of val-ues for business that promote human rights; protection of labour and elimination of all forms of discrimination; the en-vironment, and anti-corruption (United Nations, 2006). The UNGC requests that businesses embrace, support, and enact this set of core values. The 10 specific principles they outline include the following (UNGC, 2008b):

• Support and respect the protection of internationally pro-claimed human rights

• Ensure business is not complicit in human rights abuses • Uphold the freedom of association and the right to

collec-tive bargaining

• Eliminate all forms of forced and compulsory labor • Effectively abolish child labor

• Eliminate discrimination with respect to employment and occupation

• Support a precautionary approach to environmental chal-lenges

• Promote greater environmental responsibility

• Encourage the development and diffusion of environmen-tally friendly technologies

• Work against corruption in all its forms, including extor-tion and bribery

The 10 values form the foundation of the six principles espoused by PRME, another notable initiative that explic-itly seeks to integrate sustainability in business education. PRME was established in 2008 as a learning network that offers a framework for the improvement and adaptation of the curriculum, research and teaching methods in business

schools. It is supported by numerous organizations includ-ing the AACSB, AI’s Business and Society Program, and Net Impact that aims to facilitate the adaptation of business education to the new after-crises realities.

The key principles PRME (2008) espouses are listed sub-sequently and aim to alter the educational methods, practices, and learning experiences that occur in business schools:

• Develop the capabilities of students to be future generators of sustainable value for business and society at large and to work for an inclusive and sustainable global economy • Incorporate into academic activities and curricula the

val-ues of global social responsibility as portrayed in interna-tional initiatives such as the UNGC

• Create educational frameworks, materials, processes, and environments that enable effective learning experiences for responsible leadership

• Engage in conceptual and empirical research that advances understanding about the role, dynamics, and impact of corporations in the creation of sustainable social, environ-mental, and economic value

• Partner with managers of business corporations to extend knowledge of their challenges in meeting social and envi-ronmental responsibilities and to explore jointly effective approaches to meeting these challenges

• Facilitate and support dialog and debate among educators, business, government, consumers, media, civil society or-ganizations, and other interested groups and stakeholders on critical issues related to global social responsibility and sustainability

Another major global initiative that fosters the integra-tion of sustainability issues in business educaintegra-tion is the AI’s Center for Business Education that seeks to inspire future business leaders to innovate at the intersection of corporate profits and social impacts. Their objective is to radically re-orient business education to embrace the principles of corpo-rate citizenship and sustainability, and promote values-based leadership. Their key exploration areas include poverty re-duction and global relations that closely relate to global hu-man rights challenges (Aspen Institute, 2010). AI, similar to UNGC and PRME, strongly emphasizes social sustainability issues, and human rights in particular. Similarly, Realizing Rights: the Ethical Global Initiative (EGI), a partnership of AI, Columbia University, and the Council of International Human Rights Policy, also serves to facilitate the integration of human rights and the social components of sustainabil-ity within business education. Realizing Rights: EGI has programs in the areas of global health, trade and develop-ment, migration, and women’s leadership. The primary aim of Realizing Rights: EGI is to put human rights values and principles, such as equity and participation, at the heart of global governance and policymaking to ensure that the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable in the world are addressed

120 J. PALTHE

TABLE 1

Resources for Integrating Human Rights in Business Education

Sample of organizations Associated websites for Educational tools for integrating business and human rights integrating human rights integrating human rights

Aspen Institute Business & Society Program www.aspeninstitute.org Faculty seminars & case studies on human rights in business

Business and Human Rights Center of the United Nations

www.business-humanrights.org Tools for getting started from the UN special representative for business & human rights Human Rights Watch www.hrw.org Annual World Report covering human rights conditions

in over 90 nations

Net Impact www.netimpact.org Social Impact Career Handbook & Program Guide Principles for Responsible Management Education www.unprme.org Curriculum Change & Guidance for Integrating

Principles for Responsible Management Education Realizing Rights: The Global Ethical Initiative www.realizingrights.org Human Rights Instruments & Networks

United Nations Global Compact www.unglobalcompact.org Human Rights Translated: A Business Reference Guide. Tools & Guidance Materials on Human Rights United for Human Rights www.humanrights.com Human Rights Curriculum & Education Tools. Bringing

Human Rights to Life Education Package

on the global stage. Some of their human rights values and principles include the following (Robinson, 2009):

• Acknowledge shared responsibilities for addressing global challenges and affirm that everyone’s common hu-manity doesn’t stop at national borders

• Recognize that all individuals are equal in dignity, rather than view them as objects of benevolence or charity • Embrace the importance of gender and the need for

atten-tion to the diverse impacts of economic and social policies on women and men

• Affirm that a world connected by technology and trade must also be connected by shared values, norms of behav-ior, and systems of accountability

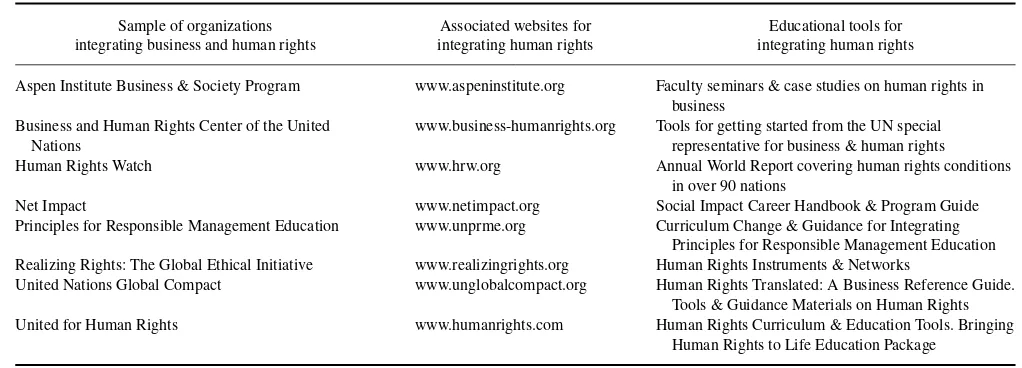

In examination of the values and principles espoused by the UNGC, PRME, AI, and Realizing Rights: EGI, note-worthy is the extensive evidence and detailed emphasis on the need to integrate human rights in business education. The prescriptions offered aim to significantly transform cur-rent educational methods, practices, and learning experiences that occur in business schools around the world. They also serve as benchmarks for business educators to ensure they are incorporating the values portrayed in initiatives similar to the UNGC into academic activities and curricula. Moreover, these detailed principles serve as helpful standards against which educators can assess the extent to which they are enabling their students to have effective learning experiences that help them become more responsible leaders of the future. While some of the main global initiaves that are relevant to human rights and business have been discussed previously, these and others, together with their associated websites and educational resources, are highlighted in Table 1.

The first column of Table 1 highlights some of the major organizations that link human rights and business education. The second column displays examples of associated websites

that integrate business and human rights. The third column exemplifies some educational tools to assist business edu-cators with getting started, curriculum design, relevant case studies, social impact career handbooks for student advising, and specialized reference guides. The primary aim of the table is to assist business educators in accessing tools and resources to facilitate the integration of human rights in their curriculum, pedagogy, and academic activities. The sample of organizations, websites, and educational tools is not in-tended to be exhaustive but rather should serve as a helpful starting point to facilitate the generation of ideas on how to integrate human rights in business education.

RESHAPING BUSINESS EDUCATION

Business students need to understand the importance of as-sessing organizational success from an economic, environ-mental and social standpoint, as well as appreciate the value of human-centered outcomes not just organization-centered outcomes of their actions (Giacalone & Thompson, 2006). Some have argued that the organization-centered worldview taught in business colleges is flawed in that it teaches stu-dents that virtually every facet of what they do is eco-nomic (Ghoshal, 2005; Pfeffer, 2005). However, despite ar-guments that economic theories also include human elements (Hambrick, 2005), the overarching trend, in response to a growing awareness of social crises around the world, is that a global shift in worldview from organization-centered to more human-centered is occurring (Giacalone & Thompson). The human-centered worldview emphasizes that business’ role in society is fundamental to the proper functioning of the world, but this role should not be earned simply as a function of financials but as a function of how well it advances the interests of humanity. Embracing a more human-centered worldview implies that when students are educated on

tainability, they are offered a more balanced perspective of the topic that explains all three dimensions, without neglect-ing the human-related aspects of business and human rights. Consequently, business educators have a moral responsibility to educate future leaders in methods that generate sustain-able value for business and society, and students need to be taught how to work toward the establishment of an inclusive and sustainable world (Adler, 2006). Moreover, they need to be taught to recognize that the leading companies of the future will place sustainability on their strategic agendas. As the previous head of PRME explained in a recentAcademy of Management Learning and Educationpublication entitled “An Interview with Manuel Escudero The United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Management Education: A Global Call for Sustainability,”

I’m registering a very clear preoccupation around the world...talking to 100–150 business schools....The buzz

is very clear: We need to redefine the future of business ed-ucation...at this moment there is no global company in the

world that doesn’t consider sustainability as a point on its agenda. (Alcaraz & Thiruvattal, 2010, p. 545)

Students need to be taught and inspired to think beyond merely protecting the environment to creating innovative methods, processes and systems that seek to promote com-munity development and enhance the social components of sustainability (Brower, 2011). These may include but are not limited to things such as promoting humanitarian issues in in-ternational conflict zones, reducing world poverty, protecting children’s rights, empowering local communities, and part-nering with human rights organizations. Also, business stu-dents should be taught about the social sustainability issues that emphasize the rights of minority populations, reduction of gender discrimination, protection of religious freedom, and seniority rights. They need to appreciate that it is not enough for organizations to merely seek to reduce unethical behavior and human rights abuses worldwide or to simply comply with human rights standards. Moreover, they need to understand human rights concerns that go well beyond the Sarbanes-Oxley model of unethical financial behavior, and refocus moral acceptability at a fundamental, human level apart from financial implications (Giacolone & Thompson, 2006).

In addition to drawing lessons from the various global initiatives that seek to integrate human rights and business, business educators should utilize more sound case stud-ies of organizations embracing each dimension of sustain-ability. Case studies give students an opportunity to de-velop their moral imagination and potentially teach them some of the warning signs associated with unsustainabil-ity (Shrivastava, 2010). Students need to be made aware of leading organization that focus on sustainability and hu-man rights. For example, Capgemini in the Netherlands, implemented a market research instrument to survey

man-agement and IT consultants on recruitment and retention issues. In exchange for participating in the survey, Capgem-ini would fund housing and schooling for underprivileged children in India. The effort resulted in the Company rais-ing 10,400 weeks of housrais-ing and education, and over 2,000 respondents submitted resumes that were consistent with the profile needed. So, in addition to Capgemini receiv-ing media attention and enhanced brand awareness as a socially responsible company, the social needs of children in India as well as the recruitment needs of the company were met.

Business educators should help students make the con-nection between the theoretical and practical relationships between human rights and business. Using case studies of organizations that specifically link these constructs in prac-tice is therefore important. Students typically want the the-ories they learn to be complemented with real-life examples and experiences that help them appreciate the links between sustainability and the business world (Stead & Stead, 2010). Therefore providing students with the opportunity to exam-ine a case such as Lego, one of the largest toy manufacturers in the world, would facilitate this conceptual connection. Lego explicitly incorporates human rights in their business practices, and demonstrates their commitment to sustainabil-ity through their Lego Group Code of Conduct introduced in 1997, which requires that their suppliers observe at a min-imum, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 2005). Similarly, it would be helpful for students to analyze a case such as Eskom, the South African electric-ity corporation that has strategically integrated human rights issues in its business policies and practices. Eskom has em-ployment equity policies, performance management indica-tors, and reward systems to protect human rights. Affirmative action, gender equity, Black economic empowerment, and Black women-owned business, and rights of people with dis-abilities are integrated in Eskom’s performance management system to ensure these human rights are respected and pro-tected (United Nations, 2007). By analyzing business cases such as these, students can more fully appreciate that a hu-man rights initiative does not have to be a huge billion-dollar project for private enterprises to make a positive difference in solving societal problems. Students need to understand that promoting human rights and thereby embracing the social dimension of sustainability could also involve something as simple as retraining workers that would otherwise be laid off, integrating human rights values in a performance man-agement system, and rewarding employees that demonstrate respect for human rights.

CORE COMPETENCIES FOR FUTURE BUSINESS LEADERS

At the 2010 UNGC Leaders Summit, where global business leaders convened to collaborate and commit to a new era of

122 J. PALTHE

sustainability, central priority areas were identified as key to effective sustainability leadership. Some of the core com-petencies that were identified at the Summit that educators should be helping their students develop include the follow-ing (UNGC, 2010):

• An understanding of how to integrate sustainability and human rights principles into business strategy, operations, and governance

• The ability to make connections between sustainability issues and actions

• An understanding of the importance of public-private part-nerships

• Knowledge and skills associated with how to be environ-mental, social, and governance change agents

Reflecting on each of these core leadership competen-cies, it is important to recognize the emphasis placed on students understanding how to integrate sustainability and human rights principles into business strategy, governance and operations. Of all the core competencies that were iden-tified at this UNGC Leaders Summit, it is noteworthy that an understanding of sustainability, and human rights specif-ically, emerged as essential leadership competencies. This is also consistent with the findings of a recent 2010 UNGC study by Accenture that found that 93% of global CEOs think sustainability issues will be critical to the future success of their business and 96% believe sustainability issues should be fully integrated into the strategy and operations of a company (Grayson, 2010). Business students need to recognize that they are the future leaders who will be helping to facilitate this integration. Similarly, business educators need to respond by comprehensively integrating sustainability and the human rights elements associated with it into every area of the field including strategic management (see Audebrand, 2010), hu-man resource hu-management (see Palthe, 2008), international management (see Collins & Kearin, 2010), and change man-agement (see Cameron, 2006), to list a few. While many schools may already have existing separate ethics courses, the magnitude of the sustainability debate and its implica-tions for every discipline demands more than another single course on the topic. As experts in this area assert:

Many...have a core business ethics course. But that is not

enough to change the business school students that are going to be leaders in the future. We need a much more integrated approach...in all disciplines. (Alcaraz & Thiruvattal, 2010,

p. 549)

As the Dean of Harvard Business School, Nittan Noria recently argued, “We have students who literally go out and help society in all walks of life, and I think that’s what busi-ness schools must be known for” (AACSB, 2010). Similarly, business educators need to do likewise by displaying an ap-preciation for and understanding of social sustainability

is-sues. Moreover, because teaching is one of the main respon-sibilities of academics, being personally passionate about the topic being taught is essential if educators are to infuse excitement into courses and students (Shrivastava, 2010). Es-sentially, colleges of business are suppliers of corporations and business educators serve as influential actors who must ensure they are preparing students to meet the expectations of the organizations in which they will be employed (Bell, Connerley, & Cocchiara, 2009).

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Students of the 21st century from all fields of study yearn for leadership based on innovation and inspiration (Boyatzis, Smith, & Blaize, 2006; Pomeroy, 2004). As Adler (2006) asserts: “Whereas money motivates some people, meaning is what inspires most people” and “the leadership challenge today is to inspire people, not simply to motivate them” (p. 296) In this light, business educators need to move beyond just teaching traditional management methods and decision-making processes relevant to past problems, unethical behav-ior, and corporate crises. Rather, it is necessary to respond by educators challenging themselves individually and as a field to more proactively imagine a world in which students and future business leaders intentionally seek to enhance the human condition and quality of human life in the work-place and the communities they serve. This requires educa-tors to consider indices of success in addition to financial ones (Parker & Chusmir, 1991), a curriculum that is oriented toward broader community good (Brower, 2011; Giacolone & Thompson, 2006), and the advancement of humankind rather than simply the accumulation of wealth (Pfeffer, 2010). These aspirations in turn will become the drivers of change that spur creative energy and innovative ideas in the field (Adler, 2006).

Some have insisted that “Any meaningful and lasting change in the conduct of corporations toward societal re-sponsibility and sustainability must involve the institutions that most directly act as drivers of business behavior, es-pecially academia” (PRME, 2008, p. 3). In essence, busi-ness educators need to play a more strategic role in moving the business sector from a risk management and compli-ance orientation to one in which students and future business leaders serve as strong advocates for human rights and ev-ery dimension of sustainability. The responsibility therefore should not and cannot just be left to governments or those in the social sciences, law or public health disciplines. As Manual Escaudero, past president of PRME contended, “We need to redefine the future of business education” (Alcaraz & Thiruvattal, 2010, p. 545).

Furthermore, as public demands on companies and indi-vidual business leaders to demonstrate responsible behavior continue to grow in coming years, the focus of these demands will increasingly be centered on human rights principles and

standards (Realizing Rights: The Ethical Global Initiative, 2010). To respond to this, business educators need to take collective action and build human rights awareness, and the values of human respect, dignity, and freedom, into curric-ula, pedagogy, and research. Moreover, as Mary Robinson, President of Realizing Rights and Former UN High Com-missioner for Human Rights, contended (Realizing Rights: The Ethical Global Initiative, 2010):

Business managers who view human rights and other social issues as just philanthropy, or as an afterthought, will face a growing number of risks. I am hopeful that we will increas-ingly see the emergence of another kind of leader—one who is able to incorporate human rights and other ethical issues into her or his decision-making. That will not only be good for business, but it will also be a powerful force in realizing human rights for all.

Business leaders of the future need to be taught how to integrate human rights into business decision making and recognize that prudent strategic decision making incorporates economic, environmental, and social sustainability elements. As Adler (2006) asserts, “Now that we can do anything, what will we do?” (p. 486). To echo and extend Eleanor Roosevelt’s 1948 UN address and sentiments, where, after all should human rights initiatives begin? Unless they have meaning in our organizations, and unless future generations of business practitioners and educators appreciate their value, they will have little meaning in the services or products our organizations offer, and we will inevitably look in vain for significant human rights progress in the larger world.

REFERENCES

Adler, N. (2006). The arts and leadership: Now that we can do anything, what will we do?Academy of Management Learning and Education,5, 486–499.

Alcaraz, J. M., & Thiruvattal, E. (2010). An interview with Maula Escudero the United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Management: A global call for sustainability.Academy of Management Learning and Education,

9, 542–550.

Aspen Institute. (2010). Mission statement. Retrieved from http://www. aspeninstitute.org/about/mission

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. (2010). HBS dean: Business plays “meaningful” role in society. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/resource centers/ ethics%2Dsustainability Audebrand, L. K. (2010). Sustainability in strategic management: The quest

for new root metaphors.Academy of Management Learning and Educa-tion,9, 413–428.

Bansal, P., & Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of eco-logical responsiveness.Academy of Management Review,43, 717–736. Bell, M. P., Connerley, M. L., & Cocchiara, F. (2009). The case for mandatory

diversity education.Academy of Management Learning and Education,

8, 597–609.

Benn, S., & Dunphy, D. (2009). Action research as an approach to integrating sustainability into MBA programs.Journal of Management Education,

33, 276–295.

Boyatzis, R., Smith, M. L., & Blaize, N. (2006). Developing sustainable lead-ers through coaching and compassion.Academy of Management Learning and Education,5(1), 8–24.

Brower, H. H. (2011). Sustainable development through service learning: A pedagogical framework and case example in a third world context.

Academy of Management Learning and Education,10(1), 58–76. Cameron, K. (2006). Good or not bad: Standards and ethics in managing

change.Academy of Management Learning and Education,5, 317–323. Christmann, P. (2004). Multinational companies and the natural

envi-ronment: Determinants of global environmental policy standardization.

Academy of Management Journal,45, 747–760.

Collins, E. M., & Kearins, K. (2010). Delivering on sustainability’s global and local orientation.Academy of Management Learning and Education,

9, 499–505.

Enkington, J. (1998).Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of sus-tainability. Gabriola Island, Canada: New Society.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good man-agement practices.Academy of Management Learning and Education,4, 75–91.

Giacalone, R. A., & Thompson, K. R. (2006). Business ethics and social re-sponsibility education: Shifting the worldview.Academy of Management Learning and Education,5, 266–277.

Grayson, D. (2010, October 3). Schools ignore sustainability revolution.

Financial Times. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/63cf95b0-cd5f-11df-ab20-00144feab49a.html

Hambrick, D. C. (2005). Just how bad are our theories? A response to Ghoshal.Academy of Management Learning and Education,4, 104–107. Haugh, H. M., & Talwar, A. (2010). How do corporations embed sustain-ability across the organization?Academy of Management Learning and Education,9, 384–396.

Marcus, A. A., & Fremeth, A. R. (2009). Green management matters re-gardless.Academy of Management Perspectives,23, 17–26.

Murray, S. (2008, May 1). Riding a wave of goodwill. Special re-port on international public sector recruitment.Financial Times. Re-trieved from http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/feccfe66-1652-11dd-880a-0000779fd2ac.html#axzz2Cnr6NdqT

Palthe, J. (2008, June 22). Human rights and human resources: The dual responsibility of global corporations. Forum on Public Policy: Oxford Round Table. Retrieved from http://www.Forumonpublicpolicy. com/summer08papers/archivesummer08/palthe.pdf

Parker, B., & Chusmir, L. H. (1991). Motivation needs and their relationship to life success.Human Relations,44, 1301–1312.

Pfeffer, J. (2005). Why do bad management theories persist?Academy of Management Learning and Education,4, 96–100.

Pfeffer, J. (2010). Building sustainable organizations: The human factor.

Academy of Management Perspectives,24(1), 34–45.

Pomeroy, A. (2004). Great places, inspired employees.HR Magazine,49(7), 46–54.

Porter, T., & Cordoba, J. (2009). Three views of systems theories and their implications for sustainability education.Journal of Management Educa-tion,1(1), 78–95.

Principles for Responsible Management. (2008). The principles for re-sponsible management. Retrieved from http://www.unprme.org/the-6-principles/index.php

Robinson, M. (2009).Mary Robinson calls on business schools to take on the human rights challenge. Retrieved from http://www.realizingrights. org/index.php?option=com content&view=article&id=139&itemid=104 Rusinko, C. A. (2010). Integrating sustainability in management and busi-ness education: A matrix approach.Academy of Management Learning and Education,9, 507–519.

Shrivastava, P. (2010). Pedagogy of passion for sustainability.Academy of Management Learning and Education,9, 443–455.

Starik, M., Rands, G., Marcus, A. A., & Clark, T. S. (2010). From the guest editors: In search of management education.Academy of Management Learning and Education,9, 377–383.

Stead, J. G., & Stead, W. E. (2010). Sustainability comes to management education and research: A story of co-evolution.Academy of Management Learning and Education,9, 488–498.

United Nations. (2005).Implementing the UN Global Compact. A booklet for inspiration. New York, NY: Author.

124 J. PALTHE

United Nations. (2006).Millennium development goals. New York, NY: Author.

United Nations. (2007).UN Global Compact annual review. 2007 Leaders summit. New York, NY: Author.

United Nations Development Program (UNDP). (2010).Poverty and so-cial impact analysis of the global economic crisis: Synthesis report of 18 country studies. Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/poverty/focus poverty assessment publications.shtml

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2004).Draft implementation plan(vol. 1). New York, NY: Author.

United Nations Global Compact (UNGC). (2008a).Human rights trans-lated. Retrieved from http://www.unglobalcompact.org/NewsAndEvents/ news archives/2008 12 05.hl

United Nations Global Compact (UNGC). (2008b). The ten prin-ciples. Retrieved from http://www.unglobalcompact.org/aboutthegc/ thetenprinciples/index.html

United Nations Global Compact (UNGC). (2008c). U.S. network meeting: Business and human rights. Retrieved from http://www. unglobalcompact.org/docs/news events/9.1 news archives/2008 05 05/ US network report april08.pdf

United Nations Global Compact (UNGC). (2010).The 2010 United Na-tions Global Compact Leadership Summit. Retrieved from http://www. unglobalcompact.org/NewsAndEvents/2010 Leaders Summit/ World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED).

(1987). Our common future. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.