Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 00:21

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Ferment in Business Education: E-Commerce

Master's Programs

Subhash Durlabhji & Marcelline R. Fusilier

To cite this article: Subhash Durlabhji & Marcelline R. Fusilier (2002) Ferment in Business Education: E-Commerce Master's Programs, Journal of Education for Business, 77:3, 169-176, DOI: 10.1080/08832320209599067

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599067

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 22

View related articles

Ferment in Business Education:

E-Commerce Master’s Programs

SUBHASH DURLABHJI

MARCELLINE R. FUSlLlER

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Northwestern State University of Louisiana Natchitoches, Louisiana

he astonishing business-world tur-

T

moil wrought by the Internet needs no introduction: It has produced con- sumer purchases of over 130 billion dol- lars since 1998, trillions of dollars in business-to-business transactions, and the longest economic expansion in U.S. history. Almost as remarkable as the e- commerce explosion is the phenomenal growth in e-commerce education. Only a couple of years ago, such programs and course offerings were virtually nonexistent, but today they are rapidly proliferating (Briones, 1999). In this research, we identified 67 graduate pro- grams offering either concentrations or majors in e-commerce at universities across North America as of November 2000. Just as business school training increased effectiveness for brick-and- mortar businesses over the past decades, e-commerce education has the potential to improve the functioning of firms in the new economy. But even as more univer- sities rush to market with such offerings, fundamental controversies remain unre- solved surrounding the need for, and the nature of, e-commerce education.Our purpose in this study was to iden- tify and describe e-commerce master’s programs in higher education to illumi- nate some of these issues. We focused on two aspects:

1. Description and enumeration of e- commerce to reveal distinctions

ABSTRACT.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Business schools are developing strategies to prepare stu-dents for the new digital economy. In this study, the authors investigated recently launched master’s programs in e-commerce by reviewing the cur- riculum and course descriptions of 67 programs that had Web listings of their programs. Findings suggest that the programs offered more nontechnical e-commerce courses than courses focusing on e-commerce technology. The authors explored the debate between those who believe e-com- merce is a new discipline requiring its own degree programs and those who would weave e-commerce content into existing functional area courses.

between concentrations and majors. These baseline data may be useful for tracking development of this area in higher education. We also examined a number of issues regarding the growth

of these programs.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2 . The relative emphasis on technical versus nontechnical content across the programs. The point of this distinction was to determine the relative emphasis between general business and technical concepts in e-commerce programs. It may also suggest the extent to which programs are developing new e-com- merce courses as opposed to using existing master’s level courses.

Few empirical studies of efforts in e- commerce higher education exist, though numerous articles on the subject

have appeared in the popular press and on the Internet. We did not evaluate the programs for their effectiveness in preparing students. Because these pro- grams are so new, outcome measures were not available. Accurate assessment of outcome measures such as career progress, salary, and promotions was impeded by the small number of gradu- ates from these programs.

Demand, Response, and Controversies

Recruiters, students, and faculty are demanding e-commerce course offer- ings with an urgency rarely seen before in academia (Dash, 2000a; Lord, 2000). In Fall 1999, the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business had to post

monitors at the door after

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

225 studentstried to register for an e-business strate- gy class that had seats for 65. Similar stampedes erupted at the University of California at Berkely, where fire mar- shals intervened. At the MIT Sloan School of Management, a third of the student body signed up for the new e- commerce track (Lord). Demand for employees with training in e-commerce capabilities is exploding (Mangan, 1999), not only in the so-called dot-corn companies but in all businesses. Corpo- rate America is snapping up e-com- merce graduates. For example, Dell Computer’s online division hired 22

January/February 2002 169

MIT Sloan e-commerce graduates in the year 2000. The typical signing bonus for e-commerce graduates in 1999 was $22,611, 50% more than for graduates in finance or marketing (Lord).

Educational institutions are working overtime to respond to this rising tide of demand for e-commerce education. Dobbs (1999) noted that “universities are scrambling to turn the study of elec- tronic commerce into majors and

degrees” (p.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

62). Gebler (2000) pro-nounced that e-commerce has arrived as a central element of business school training and professionalization. It is increasingly becoming clear to faculty and administrators alike is that not responding is no longer an option. Schools without such educational offer- ings may experience enrollment de- creases (Dobbs).

However, the approach to offering such course content varies across schools. Controversy centers on whether e-business represents an incre- mental modification of the capabilities and strategies available to business or whether we are witnessing the birth of a new paradigm. Institutions of higher education are debating whether they should “patch” e-commerce perspec- tives into existing courses and programs or offer new courses and majors. Though some researchers have contend- ed that e-commerce should be an inte- gral part of the curriculum and that sep- arate programs and degrees are unnecessary, others have argued for spe- cialized programs in the area (Leon-

hardt, 2000; Tabor, 1999).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Separate Majors

Examples of schools with separate majors in e-commerce include North- western University, Massachusetts Insti- tute of Technology, and New York Uni- versity. Their objective is to offer intensive study of e-business and address what might be a new approach to doing business. Evidence of the need for this different approach has come from leaders in the new economy (Kuchinskas, 2000; McKenna, 1997) who have predicted, for example, that marketing will be integrated into every part of the new economy organization rather than being a separate function, as

in the past. Furthermore, brand loyalty will tend to disappear, and advertising may not be as critical as it once was. An Andersen Consulting study (Harris, 2000) addressed the definition of new roles for successful management in e- commerce. These involve activities such as accurate interpretation of the external environment and traits such as being flexible and fast. Brian Authur (Levy, 2000) summarized an apparent funda- mental difference between the old and new economies by pointing out that the main goal of organizations is no longer optimization, but rather cognization, which means “defining a new problem rather than iterating ever-better solu- tions to an old one” (p. 1). On the basis of these arguments, it seems that e-com- merce education programs should focus on the production and management of intellectual property such as research, innovation, and design.

Curriculum Integration

The Web page of the Haas School of Business at the University of California at Berkeley bluntly states that separate e-business education is patently ridicu- lous, akin to a degree in “Managing in the World of the Telephone” (Haas School of Business, 2000). Administra- tors at schools such as the University of Virginia and Columbia University are designing courses and programs that treat e-business as an inseparable part of the larger business curriculum. This approach assumes that a basic ground- ing in business is still needed in the new economy (Mitchell, 2000). In a recent address at the Internet World convention (Morrow, 2000), former U.S. Treasury

Secretary Robert Rubin noted that basic laws of economics still apply to e-busi- ness. A general business problem-solv- ing framework might be the most important contribution that an educa- tional program can make in preparing students for the new economy (Fitz- patrick, 2000a). E-commerce facts and content may be obsolete sooner than students can finish a program. Integra- tion of e-commerce into established business courses also may force stu- dents to examine the social, global, psy- chological, and ethical aspects of this approach to commerce (Fitzpatrick,

2000b; Williams, Kwak, Morrison,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

&Oladunjoye, 2000).

Technical Versus Nontechnical Focus

Aside from the debate on whether to integrate e-commerce into a business program or offer it separately, there is also a lack of clarity concerning the extent to which such courses should emphasize technology as opposed to functional business areas. Should cours- es emphasize the technology that enables e-business or focus on the effect of technology on business strategy and decisions? Do e-business capabilities require a technological foundation, or can students function effectively in e- business firms without knowledge of the enabling technology? Who should initi- ate and “own” e-business education- the computer information systems fac- ulty or the management faculty? E-business programs are being offered by both business schools and, primarily, technological schools such as the Stevens Institute of Technology.

Kalakota and Robinson

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( 1 999) suggest-ed that technology could no longer be an afterthought to business strategy but an integral part of every phase of strate- gy development. But what this means in terms of business education is not clear.

Method

Web Searches

In February and November 2000, we conducted exhaustive Web searches using various search engines to analyze Web page descriptions of e-commerce programs and course offerings by insti- tutions of higher education. Also, we accessed particular Web pages of uni- versities reputed in the popular press or other publications to have an e-com- merce program. Moran (1999) described 10 successful new initiatives at top-rated business schools for inte- grating students into the digital econo- my. We examined all the programs list- ed on the Web site of the American Association of Colleges and Schools of Business (AACSB, the national accred- itation organization for business educa- tion; AACSB, 2000). Some established e-commerce programs did not have a

170 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Businessclear Web presence or one that we were able to locate.

These programs took the form of e- commerce concentrations in master’s programs or degrees in e-commerce. Others involved certificates in e-com- merce. Most programs were at the mas- ter’s level, but a few were available for undergraduates. They varied consider- ably in their focus, types of courses offered, and degree requirements. We chose master’s programs for this study because they appeared to be the most common and best established of higher education e-commerce programs. We chose only those programs that were described in detail on the Web and came up with a total of 38 programs in February 2000 and 29 new programs that were added between February and November. The total number of schools offering e-commerce graduate education stood at 55. Some schools had multiple e-commerce tracks or

programs.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Course Coding

We examined programs for (a) type, (b) number of technical courses includ- ed, (c) number of e-commerce courses, and (d) number of business courses. The e-commerce courses were further iden- tified as being technical or nontechnical in nature. Courses were also classified as required or elective. The intent of the coding scheme was to provide a general picture of the types of courses offered in this area and an idea about the extent to which such programs had a technology emphasis.

We used course titles and descrip- tions to place courses in categories. Using the following guidelines, we des- ignated the courses as either (a) busi- ness, (b) technical e-commerce, (c) non- technical e-commerce, or (d) technical: I . Business courses included regular business offerings found in traditional business programs, such as Accounting, Finance, and so forth, with no systems, Internet, e-commerce, or dominant computer focus.

2. Courses specifically incorporating e-commerce and the Internet in their titles and that were also technical in nature, such as Web Programming and Security Systems for E-Commerce,

were classified as technical e-corn-

merce.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

3. The nontechnical e-commerce

designation was used for courses that referred to e-commerce or the Internet in their titles but were nontechnical; that is, they focused on functional areas such as e-marketing, e-management, and legal issues in e-commerce.

4. Courses that traditional computer information systems programs typically offer and other courses that presume a technical background were categorized as technical courses. Examples include Telecommunications Technology, Pro-

gramming, and Systems Analysis.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Findings

Program Types

In Table 1, we list the 67 programs examined. The most prevalent strategy among these programs was to offer an e-commerce concentration (or track or specialization) in existing MBA pro- grams; 30 of the programs in the present study used this strategy. These are iden- tified in Table 1 by a “C” in parentheses at the end of the program name. Two other MBA programs called the concen- tration “Technology and E-Commerce.” Other master’s programs with an e-com- merce concentration included four in CIS or MIS; four master’s of science programs in management; and one each in marketing, administration sciences, networking, and quality. When counting all of these as master’s programs offer- ing an e-commerce concentration, we found that a total of 44 programs or 66% of the sample used this route fore- commerce coverage. Concentration requirements typically comprised four or five courses from a longer list of elec- tives. Of the remaining 23 programs, 22 were billed as majors or degrees in e- commerce. One program was listed as post-MBA.

Course Categories

In Table 1, we display the raw fre- quencies and percentages of courses in each of the categories. The courses included are those listed as available to satisfy the e-commerce component of the master’s programs and do not neces-

sarily represent all the courses required for the degree. This especially was the case for the programs with e-commerce concentrations. We computed percent- ages within each school’s individual program to assess the composition of each program with regard to types of courses and whether they were required or elective.

An examination of the percentages within a given course type, across pro- grams, permits assessment of the extent to which that course type was represent- ed in the sample. The lowest bound across all the course categories was zero, indicating that no program includ- ed all of the course categories. For example, the percentage of required e- commerce technical courses in Allen- town College’s program was zero, which means that none of their courses were coded as such.

The total number of courses identi- fied under each category is listed at the bottom of its column in Table 1. Out of the 855 courses, 406 had a specific e- commerce focus, of which 292 were coded as having a nontechnical focus and 114 as having a technical bent. At least one nontechnical elective e-com- merce course was offered in 42 of the 67 programs. Thirty programs required at least one technical e-commerce course. Furthermore, it appears that nontechni- cal e-commerce courses were required in more programs than were technical e- commerce courses.

We examined the highest percentages of each course type across programs. The highest proportion of required busi- ness courses (56.3%) appeared to be in programs at Northwestern University, Our Lady of the Lake University, and the University of Colorado. The largest percentage of business electives was at Wharton University (69.7%). The pro- gram with the largest percentage of required e-commerce technical courses

was Worcester Polytechnic Institute

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(33.3%), and that with the largest pro- portion of electives was the University of Maryland (37.5%). The nontechnical e-commerce category was best repre- sented at National Graduate School (Massachusetts) for required courses (100%) and Allentown College and Duke University for electives ( 1 00% of the program). For technical courses,

January/February 2002 171

TABLE 1. Master’s E-Commerce Programs: November 2000

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Courses School

Technical Nontechnical

e-commerce Technical Business e-commerce

Required Elective Required Elective Required Elective Required Elective Lab

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

~~~~

State Program

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

n % n % n % n % n % n % n % n % n % T o t a l Allentown CollegeBentley College

Boston U Metropolitan College Capella College

Capitol College Camegie-Mellon U

Case Western U Case Western Reserve U

Claremont

College of Notre Dame Creighton

Dalhousie U

DePaul U

Duke U Emory U

Georgia State U

Georgia State U

Georgia State U

Georgia State U Golden Gate U

Illinois institute of Technology Illinois Institute of Technology Johns Hopkins U

Loyola U Marlboro College McMaster U Mercy College MIT

National Graduate School National U

National U

North Carolina State U

PA MA MA MN MD MA OH OH CA CA NE CAN IL NC GA GA GA GA GA CA

IL

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

IL MD IL VT CAN NY MA MA CA CA NC MBA-EC(C) MS-Emktg MS-ADMN-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MS-EC-MGT MS-EC MBA-EC(C) M-MGT-EC(C) MS-EC MS-EC MS-EC M-EC MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC MBA-EC(C) M-CIS-EC(C) MS-EC MBA-EC MBA-EC(C) MS-EC M-CIS-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MS-E-Strategy MBA-EC(C) MS-EC MBA-EC(C) MS-Quality-EC(C) MBA-EC( C) MS-EC MS-MGT-EC(C)

0 0.0

3 23.1

0 0.0

0 0.0

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 41.7

6 26.1 0 0.0

3 25.0

0 0.0

0 0.0

1 5.0

0 0.0

0 0.0 0 0.0 4 44.4

1 7.7 0 0.0

1 7.1 7 36.8 7 24.1

0 0.0 0 0.0

0 0.0

0 0.0

1 11.1

2 10.5

0 0.0

2 5.9

0 0.0 0 0.0

I 7.1 0 0.0

North Carolina State U NC MS-NETWRKEC(C) 0 0.0

0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

5 38.5 0 0.0 0 0.0

12 57.1 1 4.8 0 0.0

0 0.0 0 0.0 1 20.0 0 0.0 2 16.7 0 0.0

5 21.7 3 13.0 0 0.0 3 25.0 0 0.0 2 16.7 0 0.0 3 25.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 2 25.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 2 20.0 0 0.0

0 0.0 2 10.0 2 10.0

6 23.1 2

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

7.7 4 15.4 3 17.6 0 0.0 5 29.40 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

1 7.7 0 0.0 2 15.4 1 33.3 0 0.0 0 0.0

5 35.7 1 7.1 0 0.0

1 5.3 0 0.0 2 10.5

10 34.5 1 3.4 4 13.8

0 0.0 1 20.0 0 0.0

5 26.3 4 21.1 2 10.5 0 0.0 0 0.0 5 35.7

1 10.0 0 0.0 2 20.0

0 0.0 2 22.2 0 0.0

2 10.5 1 5.3 0 0.0

2 12.5 2 12.5 5 31.3 17 50.0 1 2.9 1 2.9

0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 1 14.3 0 0.0 0 0.0 4 28.6 0 0.0

0 0.0 0 0.0 2 33.3

0 0.0 0 0.0 1 16.7

0 0.0

1 7.7

3 14.3

1 20.0

5 41.7

3 13.0

0 0.0

6 50.0 2 25.0

8 80.0

3 15.0 5 19.2 2 11.8

0 0.0 0 0.0 3 23.1

0 0.0

2 14.3 4 21.1 3 10.3 4 80.0

8 42.1

0 0.0

2 20.0 3 33.3 4 21.1 6 37.5 3 8.8

4 100.0 3 42.9 6 42.9

0 0.0 0 0.0

7 100.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

1 7.7 3 23.1 0 0.0

0 0.0 1 4.8 4 19.0 3 60.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 4 17.4 0 0.0

5 41.7 0 0.0 2 16.7 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 3 37.5 0 0.0

0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2 10.0 2 10.0 7 35.0 2 7.7 0 0.0 6 23.1 2 11.8 0 0.0 5 29.4

5 100.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

5 55.6 0 0.0 0 0.0 5 38.5 1 7.7 0 0.0

2 66.7 0 0.0 0 0.0 4 28.6 1 7.1 0 0.0

4 21.1 1 5.3 0 0.0

2 6.9 0 0.0 2 6.9

0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

2 14.3 0 0.0 7 50.0

4 40.0 1 10.0 0 0.0

0 0.0 3 33.3 0 0.0

0 0.0 4 21.1 5 26.3

1 6.3 0 0.0 0 0.0

4 11.8 2 5.9 3 8.8

0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

0 0.0 3 42.9 0 0.0

0 0.0 3 21.4 0 0.0 3 50.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

2 33.3 3 50.0 0 0.0

0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0

0.0 7

0.0 13

0.0 21

0.0 5

0.0 12

8.7 23 0.0 12

0.0 12 12.5 8

0.0 10 5.0 20 3.8 26

0.0 17

0.0 5

0.0 9 0.0 13

0.0 3

0.0 14

0.0 19 0.0 29 0.0 5

0.0 19

0.0 14

0.0 10

0.0 9 5.3 19

0.0 16 2.9 34 0.0 4 0.0 7

0.0 14 16.7 6

0.0 6

[image:5.612.82.749.145.569.2]New Jersey Institute of Technology New Jersey Institute of

Technology Northwestern U Our Lady of the Lake U

Purdue U Regis U

Rensselaer Polytechnic Rutgers U

Southern Illinois U Stanford U

Temple U Temple U Texas A&M U

Texas A&M U

Texas Christian U U of Colorado U of Dallas

U of Dallas

U of Dallas

U of Denver

U of Georgia

U of Maryland U of Memphis U of Michigan U of New Brunswick U of PA Wharton U of Rochester U of San Diego U of Texas U of Wisconsin Vanderbilt U Wake Forest U

Westchester

Worcester Polytechnic Institute No. programs with at least

one course NJ NJ IL TX IN

co

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

N Y NJ IL CA PA PA TX TX TX

co

TX TX TXco

GA MD TN MI CAN PA NY CA TX WI TN NC PA MA MBA-EC(C) MS-MGT-EC( C) M-MGT-TEC MBA-EC MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-ECMS-EC (Post MBA) MS-MIS-EC(C) MS-MKT-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC MBA-EC(C) M-MGT-EC M-MGT-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) M-CIS-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MS-EC MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-EC(C) MS-EC MBA-EC(C) MS-EC MBA-TEC(C) MBA-EC(C) MBA-TEC(C) MBA-EC(C) Total courses

0 0.0

0 0.0

9 56.3 9 56.3

0 0.0

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1 9.1 0 0.0

0 0.0

0 0.0

1 7.1 10 45.5

1 10.0 0 0.0 4 17.4 3 50.0 9 56.3

0 0.0

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1 10.0

4 40.0 0 0.0

0 0.0

0 0.0

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1 8.3

0 0.0 0 0.0

1 3.0

0 0.0 0 0.0

1 5.3 0 0.0 0 0.0

0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

99 28

3 30.0 0 0.0 1 10.0 4 40.0 0 0.0 0

0 0.0

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 31.3 00 0.0 0 0.0 0

1 11.1 1 11.1 0

1 9.1 0 0.0 0

0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0 0.0 1 11.1 2 0 0.0 0 0.0 2 7 50.0 0 0.0 1 0 0.0 2 9.1 0 0 0.0 1 10.0 0

0 0.0 0 0.0 0

8 34.8 0 0.0 1

2 33.3 0 0.0 0

0 0.0 1 6.3 0 0 0.0 0 0.0 1 3 30.0 1 10.0 0 0 0.0 2 20.0 0 1 20.0 0 0.0 0 2 40.0 0 0.0 0

0 0.0 0 0.0 3

0 0.0 0 0.0 0 9 45.0 0 0.0 2 0 0.0 0 0.0 0

23 69.7 0 0.0 0 6 60.0 0 0.0 0

1 8.3 1 8.3 0

5 26.3 0 0.0 1 9 39.1 1 4.3 1

0 0.0 0 0.0 5 4 36.4 0 0.0 0

0 0.0 1 14.3 0

3 50.0 2 33.3 0

171 54 60 34 30 26

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 22.2 25.0 7.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 10.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 5.3 4.3 29.4 0.0 0.0 0.0

2 20.0 2 20.0 2 12.5

5 31.3

4 44.4 0 0.0

4 100.0

1 11.1 2 25.0 0 0.0

4 18.2 4 40.0 2 20.0

2 8.7 0 0.0

5 31.3 0 0.0

5 50.0 4 40.0 0 0.0

0 0.0 0 0.0 3 25.0 0 0.0

0 0.0

0 0.0

2 20.0 3 25.0 1 5.3 6 26.1

0 0.0

1 9.1 4 57.1 1 16.7 163

48

3 30.0 1 10.0 0 0.0 3 30.0 1 10.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

0 0.0 2 12.5 0 0.0

3 33.3 0 0.0 0 0.0 4 36.4 1 9.1 4 36.4 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 5 55.6 0 0.0 0 0.0

4 50.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 4 28.6 0 0.0 1 7.1 0 0.0 5 22.7 0 0.0 0 0.0 4 40.0 0 0.0

0 0.0 3 30.0 5 50.0 2 8.7 1 4.3 5 21.7

1 16.7 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 1 6.3 0 0.0

4 80.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0

2 40.0 0 0.0 2 40.0

1 20.0 0 0.0 2 40.0 3 37.5 0 0.0 2 25.0

0 0.0 5 41.7 2 16.7 5 25.0 0 0.0 3 15.0 6 85.7 0 0.0 1 14.3

2 6.1 0 0.0 7 21.2 0 0.0 0 0.0 2 20.0 3 25.0 3 25.0 1 8.3 2 10.5 6 31.6 3 15.8 1 4.3 0 0.0 4 17.4 3 17.6 0 0.0 9 52.9 2 18.2 4 36.4 0 0.0

1 14.3 1 14.3 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 129 73 94

42 29 25

0 0.0 10 0 0.0 10

0 0.0 16 0 0.0 16 0 0.0 9

0 0.0 11 0 0.0 4

0 0.0 9 0 0.0 8

0 0.0 14

1 4.5 22

0 0.0 10 0 0.0 10

0 0.0 23 0 0.0 6

0 0.0 16 0 0.0 5 0 0.0 10

0 0.0 10 0 0.0 5

0 0.0 5 0 0.0 8

1 8.3 12

1 5.0 20 0 0.0 7

0 0.0 33

0 0.0 10

0 0.0 12

0 0.0 19

1 4.3 23

0 0.0 17

0 0.0 11 0 0.0 7 0 0.0 6 12 855

11

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Nore. EC denotes e-commerce; (C) denotes an e-commerce concentration in existing MBA courses; TEC denotes telecommunications and e-commerce.

North Carolina State had the highest

percentage required

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(50%), and Vander-bilt University had the highest percent- age in electives (52.9%).

Surprisingly few of the programs had a Lab component. Lab courses were cat- egorized as those that required hands-on e-commerce experience such as intern- ships or practicum. Courses listed as “e- commerce project” were classified as nontechnical e-commerce unless they specifically required a hands-on compo-

nent in the course description.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Discussion

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

DifSerentiated Versus Integrated Programs

Our study’s results indicate that a large number of new courses have been developed specifically for both techni- cal and nontechnical e-commerce cov- erage. We identified at least 22 pro- grams as majors or degrees in e-commerce. The proliferation of new courses and degrees reflects a conclu- sion by faculty and deans that e-com- merce involves fundamentally new con- cepts and processes. Donald Jacobs, dean of Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, stated that “success on the Internet calls for a very different way of thinking than managers in tradi- tional businesses are trained for” (Leon- hardt, 2000, p. 7). Deans from schools of business such as Wharton and North- western have claimed that integrating e- business into functional area courses is too slow or just plain “crazy.” Joseph Morone, president of Bentley College in Massachusetts, justified the creation of entirely new programs by declaring that the Internet represents a revolution that is literally transforming every kind of company: “We have to rethink the guts of the MBA” (Lord, p. 64).

Deans from other well-regarded busi- ness schools have pronounced the rush to offer separate e-commerce programs a moneymaking gimmick and a fad (Leonhardt, 2000; Mitchell, 2000) intended to attract students but poten- tially not providing what is needed to succeed in the new economy. “You’re missing the point if you set up a sepa- rate program,” stated Edward Snyder, dean of the University of Virginia’s Dar-

den School (Leonhardt, p. 7). Snyder’s views have been echoed by many pro- fessors and administrators who are con- vinced that e-commerce will not be con- sidered a distinct area of study in the future. Fitzpatrick (2000b) argued that it will permeate the whole business cur- riculum. Leonhardt suggested that this debate actually mirrors a dilemma that brick-and-mortar companies are tack- ling: “Some companies, like General Electric, have directed managers in every department to rethink their busi- ness with the Internet in mind, while others have set up separate Web divi- sions meant to stay free of corporate bureaucracy” (p. 7).

Data from our study do not provide us with information about the preva- lence of this view of e-business educa- tion, because schools that have adopted this integrated approach do not have new programs to announce. Few of these schools announced their philoso- phy explicitly on their Web pages. The Haas School of Business at the Univer- sity of Berkeley is an exception; it devoted a separate page to “Why Haas has an integrated e-business curricu- lum.” Amazingly, their integrated approach was justified by the same argument-that the Internet represents a fundamental revolution in business- used to support the differentiated approach: “The Haas School integrates the study of e-business into the existing MBA curriculum instead of creating a separate track, as some schools have done. Haas faculty members believe the Internet is so fundamental that it must be taught across the entire MBA cur- riculum” (Haas School of Business, 2000).

Technology-Centered or Business- Centered Programs

E-commerce education appears ac- cessible to MBA students in general, not simply to those who are technically inclined. Business and nontechnical e- commerce courses were well represent- ed in the composition of the programs. Kalakota and Robinson (1999) urged CEOs to “think e-business design, not just technology” (p. 53). Our study’s results suggest that there is a greater nontechnology emphasis in most of the

programs investigated. The ratio of total nontechnical e-commerce courses to technical e-commerce courses was 2.5 to 1. But it is unclear why the programs are structured this way. Is it because careful analysis and debate led to the conclusion that this is the content that students need? Or is this structure all that business schools are able to offer without a wholesale retooling of faculty capabilities? That is, if the majority of the faculty are not prepared to teach technical e-commerce courses, then the program could not emphasize this mate- rial. Regardless of the reason for the prevalence of nontechnical courses, if programs assume this focus, then it

makes sense to integrate e-commerce into the existing curriculum. Such course material probably does not entail a radical technological departure from what is currently being taught. Howev- er, for programs with a unique technical emphasis, a separate degree plan might be necessary.

Another perspective on the debate over technical-versus-nontechnical emphasis comes from Mitchell (2000), who suggested that degree programs emphasizing technology appeal to dif- ferent kinds of students than do MBA programs with an e-commerce concen- tration. The former attract students who have a greater technology bent and interest in learning the business basics, whereas MBA degrees with e-com- merce concentrations tend to attract stu- dents who wish to dig deeper into the business aspect and learn enough tech- nology to give those business lessons some context. An MBA with concentra- tions may also have other advantages: A concentration can be developed into a full program if the need should arise and may provide the flexibility for schools to accommodate both nontechnical and technical specializations. In today’s tur- bulent environment, such flexibility may be the most prudent approach.

Other Issues

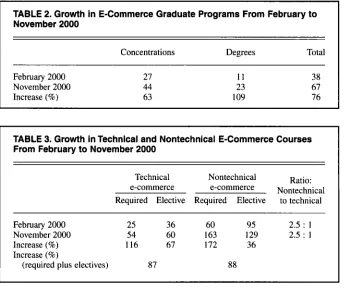

To gauge the pace at which new e- commerce programs are being launched, we compared the data collect- ed in February 2000 with the data from November 2000 (see Table 2). A new program was announced almost on a

174 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Businessweekly basis-our research identified 29 new programs launched in the 8 months between February and Novem- ber 2000. The total number of programs grew from 38 to 67, a growth rate of 76% in 8 months. Interestingly, the number of programs offering concentra- tions increased by 63%, whereas the number of degree programs more than doubled, suggesting that business schools are increasingly convinced that e-business represents a new discipline rather than only a different aspect of business.

The ratio of nontechnical e-com- merce courses to technical e-commerce courses remained unchanged between February and November 2000 (see Table 3), but there seemed to be a grow- ing emphasis on requiring nontechnical courses rather than on offering them as electives. The level of required nontech- nical e-commerce courses recorded in November was 172% higher than the February level, whereas elective non- technical e-commerce courses increased by only 36% during the same time. The recent dot-com debacle in the stock markets may be alerting educators to the need for more attention to business basics. Many of the failed dot-com start- ups were launched by information tech-

nology professionals who may not have an adequate understanding of the foun- dations of a successful business enter- prise. Griffin (2000) reported that “the business plan-endangered for the last two and a half years-is making a comeback” (p. 216), indicating that ven- ture capitalists are beginning to require evidence of managerial and marketing competence from would-be dot-com entrepreneurs.

In the future, accreditation standards may incorporate e-business coverage. In addition to the extensive e-business sec- tion on its Web page, the AACSB has held conferences on the subject. Many of the issues that we have addressed in the present study may be debated with- in the AACSB before any new guide- lines are issued. Budget constraints and competition are also forcing universities to limit the number of credit hours required for completion of degrees, which suggests that e-commerce cover- age will come at the expense of, rather than in addition to, current course work. In any case, business faculty could be faced with the need to retool in this area. Furthermore, the nature of e-business demands frequent changes to course content and process, i n some cases

every time the course is offered. In spite

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TABLE 2. Growth in E-Commerce Graduate Programs From February to November 2000

Concentrations Degrees Total February 2000

November 2000

Increase

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(%)27

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

44 63

11

23 109

38 67 76 TABLE 3. Growth in Technical and Nontechnical E-Commerce Courses From February to November 2000

Ratio: Technical Nontechnical

e-commerce Nontechnical Required Elective Required Elective to technical

e-commerce

February 2000 25 36 60 95 2.5 : 1

November 2000 54 60 163 129 2.5 : 1

Increase (%) 116 67 172 36 Increase (%)

(required plus electives) 87 88

of constant budget constraints, universi- ties may be required to reduce or modi- fy faculty teaching loads.

An alternative to continual course content changes might be to focus on teaching problem-solving skills for the new economy. E-commerce facts often become outdated before students can even finish a program. Therefore, a more effective focus for teaching might be on logic and thinking processes con- cerning e-commerce strategy. There is a great deal of literature that can be used for development of course material on environmental scanning, fast and accu- rate decisionmaking ( e g , Eisenhardt & Bourgeois, 1988), and creativity. A process emphasis may be more useful than teaching content regarding busi- ness practice in turbulent environments. Just as e-commerce seems to have given rise to new and different ways of doing business, it may do the same with regard to education. For example, indi- vidual professors may decide to bypass the university and offer their courses on- line directly. Traditional brick-and-mor- tar universities, on-line universities, pri- vate technology companies, and even textbook publishers are already putting reportedly high quality course materials on-line (Dash, 2000b; Johnston, 2000). Even MBA and MS degrees are now fully available online, with no residency requirements-examples include the Monterrey Institute for Graduate Stud- ies and the University of Phoenix. A new breed of “university” with no phys- ical campus at all is also emerging, with e-commerce education as a primary focus. An example is the new Graduate School of E-commerce, billed as the first and only fully on-line program exclusively dedicated to electronic com- merce, and offering an MBA in elec- tronic commerce.

Though all these options allow stu- dents more choices as consumers of e- commerce education, they also consti- tute escalating competition for universities, potentially increasing the likelihood that programs will be devel- oped without adequate deliberation. Arthur Levine, president of Columbia University Teacher’s College, indicated that this might be a scary situation for students and educators (Johnston,

2000). The advent of e-commerce and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

January/February 2002

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

175 [image:8.612.47.391.449.737.2]e-education may lead to more frequent and radical changes in higher education-

al methods than anticipated even

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

a yearago. The rapid arrival of e-commerce programs suggests that a revolutionary change in business school education

may be at hand.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

NOTE

An earlier version of this article was presented at the Decision Sciences Institute annual confer- ence in Orlando, Florida, November 2000.

REFERENCES

American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of

Business (AACSB). (2000).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

E-business educa-tion. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/e- business/index.html

Briones, M. G. (1999, March 29). E-commerce

master’s programs set to explode. Marketing

News, 19-20,

Dash, J. (2000a. August 7). MBA programs expand e-commerce course offerings. Comput-

enuorld, 20. Retrieved from http://www.com-

puterworld.com/cwi/story/O, 1 199,NAV47_STO

4819 1 ,OO.html

Dash, J. (2000b, September 4). IT leaders give online universities high marks. Computerworld. Retrieved from .http://www.computerworld.

com/cwi/story/O, 1 199,NAV47_ST049475,00.

html

Dobbs, K. (1999). New rage on campus: E-com- merce degrees. Training, 36, 62-64.

Eisenhardt, K. M.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Bourgeois, L. J., 111. (1988.)Politics of strategic decision making in high-

velocity environments. Academy of Manage-

ment Journal, 31, 737-770.

Fitzpatick, M. (2000a, May 29). A new kind of teamwork in e-business education. Chicago Tri-

bune. Retrieved from http://www.chicagotri- bune.com

Fitzpatrick, M. (2000b, May 29). Education on the fly: Creating the new e-business curriculum.

Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from http://www. chicagotribune.com

Gebler, D. (2000). The future of e-commerce 101.

E-Commerce Times. Retrieved from http://

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

www.ecommercetimes.com/news/arti-

cles2000/000809-2.shtml

Griffin, J. (2000, October 24). Back to business plans and sanity. Business 2.0, 216.

Harris, J. G. (2000). Information and the manager

in the new economy. “Sidebar” in J. D. Rollins,

D. A. Marchand, & W. J. Kettinger, The infor-

mation edge: How to get the full value

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of infor-mation in the new economy. Outlook Special Edition: The eSeries II, Andersen Consulting.

Retrieved from http://www.ac.com/ideas/Out-

looWspecia12000-2/se2-sidebar3. html Haas School of Business. (2000). Why Haas has

an integrated e-business curriculum. Retrieved

from http://www.haas.berkeley.edu/mba/pro-

gramguide2000/studentadvantage/technolo-

gy6.htm

Johnston, M. (2000). Web may undermine univer- sities, says college pres. The Standard: Intelli-

gence for the Internet Economy. Retrieved from

http://www.thestandard.com/articIe/display/ 0.1 15 1.13 132,OO.html

Kalakota, R., & Robinson, M. (1999). E-business:

Roadmap for success. Reading, MA: Addison- Wesley.

Kuchinskas, S. (2000, November 14). The end of marketing. Business 2.0, 134-1 39.

Leonhardt, D. (2000, January 16). At graduate schools, a great divide over e-business studies.

The New York Times, Business Section, 7. Levy, D. (2000). Managing the new economy

demands new skills, focus. Stanford News. Retreived from http://www.stanford.edu/dept/ news/pr/OO/futureprof823.htmI

Lord, M. (2000, April 10). Suddenly, e-commerce

is the hot new specialty. U.S. News & World

Report, 62-64.

Mangan, K. S. (1999, April 30). Business students

flock to courses on electronic commerce.

Chronicle of Higher Education, A25-A26. Mitchell, M. (2000, September 1 I ) . A difference

of degree. CIO Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.cio.com/archive/O9O 100-degree. html

McKenna, R. (1997). Real time: Preparing for the

age of the never satisfied customer. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Moran, S. (1999, October 1). MBA.com. Business

2.0, 123-149.

Morrow, J. M. (2000,October 27). Rubin: New economy subject to old rules. NewsFactor Net-

work. Retrieved from http://www.newsfactor. com

Saracevic, A.T. (2000, October 10). Hope for the holidays. Business 2.0, 146-152.

Tabor, M. B.W. (1999, September 22). Latest hit on campus: Crescendo in E-major. New York

Times, p. 12.

Williams, H. J., Kwak, Y., Morrison, J. L., &

Oladunjoye, G . T. (2000). Teaching the effects of electronic commerce on business practices

and global stability. Journal of Education for

Business. 75, 178-1 86.

176 Journal of Education for Business