ISSN: 1606-6359 print/1476-7392 online DOI: 10.3109/16066359.2011.558955

Beginning gambling: The role of social networks and environment

Gerda Reith

1& Fiona Dobbie

21

School of Social and Political Sciences, Glasgow University, Adam Smith Building,

Glasgow G12 8TT, Scotland, UK, and2National Centre for Social Research, 73 Lothian Road, Edinburgh EH3 9AW, UK

(Received 24 September 2010; revised 21 January 2011; accepted 24 January 2011)

This article reports findings from the first phase of a longitudinal, qualitative study based on a cohort of 50 gamblers. The overall study is designed to explore the development of ‘gambling careers’. Within it, this first phase of analysis examines the ways that individuals begin gambling, focusing on the role of social relationships and environmental context in this process. Drawing on theories of social learning and cultural capital, we argue that gambling is a fundamentally social behaviour that is embedded in specific environmental and cultural settings. Our findings reveal the importance of social networks, such as family, friends and colleagues, as well as geographical-cultural environment, social class, age and gender, in the initiation of gambling behaviour. They also suggest that those who begin gambling at an early age within family networks are more likely to develop problems than those who begin later, amongst friends and colleagues. However, we caution against simplistic interpretations, as a variety of inter-dependent social factors interact in complex ways here.

Keywords: Gambling, qualitative sociology, social learning, cultural capital, social networks, environment

INTRODUCTION

While it is recognised that gambling is an intrinsically social activity, research relating to its social contexts and meanings remains scarce. In particular, the ways that gambling behaviour is begun and learned tends to be framed within ‘deficit’ models that focus on the individual psychological factors that lead to problem-atic behaviour early in the life course.

Much research to date has focused on the associa-tions between a number of mainly psychological and demographic factors with the onset of gambling and problem gambling (see, e.g. Derevensky & Gupta, 2004). For example, a number of studies have found that individuals whose parents gamble, especially at problematic levels, are more likely to develop prob-lems themselves when they reach adulthood (Abbott & Volberg, 2000; Derevensky & Gupta, 2007; Raylu & Oei, 2002). Other research has demonstrated the role of parents in introducing their children to gambling (see Kalischuk, Nowatzki, Cardwell, Klein, & Solowoniuk, 2006 for a review). Through their own participation in gambling games, they may display attitudes that normalise and condone the activity and through behaviour such as, for example, providing money to gamble or buying tickets for games, may actively encourage it. This social learning or ‘modelling’ of behaviour has also been illuminated through a limited number of small-scale qualitative studies, which found that families established norms within which gambling was regarded in a positive light, and provided an environment in which the techniques for playing could be learned (Orford, Morrison, & Somers, 2003; White, Mitchell, & Orford, 2000). A New Zealand study found that problem gamblers were twice as likely as recre-ational ones to report they had been introduced to gambling by their families, followed by friends (Abbott, 2001); a finding that has been reported elsewhere (Gupta & Derevensky, 1998; Jacobs et al., 1989). Research from Great Britain has found that problem gamblers are three times more likely than recreational ones to report a parent with gambling problems (Fisher, 1999). This trend has been described as the ‘intergenerational multiplier effect’ (Abbott, 2001), with repeated generations of individuals adopt-ing the habits of those before them. This has been

Correspondence: G. Reith, School of Social and Political Sciences, Glasgow University, Adam Smith Building, Glasgow G12 8TT, Scotland, UK. Tel: 44 (141) 330 3859. Fax: 44 (0141) 330 3554. E-mail: gerda.reith@glasgow.ac.uk

483

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15

found to follow gendered patterns, although fathers appear to increase the risk of their sons developing gambling problems more than mothers do their daughters (Walters, 2001). In addition, the younger an individual is when they begin playing, the more likely they are to have problems in adulthood (Fisher, 1993; Gupta & Derevensky, 2008; Wood & Griffiths, 1998).

Peer groups can also play a role in the development of gambling behaviour, with some young people playing to socialise, display identity and demonstrate skill to friends (Fisher, 1993; Griffiths, 1995; Huxley & Carroll, 1992). Many studies have found that adoles-cent gambling is more common among males; that boys begin earlier than girls, play more often and are more at risk of developing problems (Fisher, 1999; Jacobs, 2000). This mirrors adult patterns of gambling, which are also highly gendered (Volberg, 2001; Wardle et al., 2007). Whereas considerable evidence links problem gambling to lower socio-economic status and low income (e.g. Orford, Sproston, Erens, White, & Mitchell, 2003; Shaffer, LaBrie, LaPlante, Nelson, & Stanton, 2004), the evidence on adolescent gambling and socio-economic status is less clear cut, with some studies suggesting a relationship between increased participation and lower social class, and others refuting this (Fisher, 1993).

As we have seen from this brief overview, a considerable body of research has focused on the influences upon adolescent gambling (and particularly problem gambling) behaviour. However, less attention has been paid to the wider social and cultural contexts within which individuals begin gambling, and even less to the experiences and attitudes associated with those early beginnings. So, while we know about some of the individual determinants of beginning gambling, we know far less about the actual meanings and contexts of such crucial early behaviour.

DISCUSSION

At this point, it is helpful to consider studies that have explored the ways that individuals begin to use drugs. Classic studies by Becker (1953, 1963) and Zinberg (1984) in particular, have shed light on processes of beginning drug use, and we argue that these can be used to illuminate some themes related to beginning gambling. For example, Becker (1953, 1963) focused on the process of ‘becoming’ a drug user in terms of the learning and labelling of new roles and identities. Contrary to explanations that relied on the idea of intrinsic traits that predisposed individuals towards particular types of behaviour, Becker showed that behaviour was learned through interaction with the social environment, and therefore variable. Learning how to smoke, learning to recognise the effects of such smoking, and finally, interpreting these as pleasurable were necessary steps towards becoming a drug user. He argued that this was a fundamentally social

process that involved translating a neutral experience into a recognisable ‘drug experience’ involving the appropriate social surroundings, prompts and guidance from more experienced users.

Rather than the notion of ‘antecedent predisposi-tions’, Becker (1953) argued that ‘the presence of a given kind of behaviour is the result of a sequence of social experiences during which the person acquires a conception of the meaning of the behaviour and percep-tions and judgements of objects and situapercep-tions, all of which make the activity possible and desirable’ (p. 235). In a similar vein, the ethnographic studies of Zinberg (1984) and Zinberg and Shaffer (1985, 1990) found that the experience of drug-taking was created at least as much through social interaction as by the physical properties of substances themselves. Zinberg (1984) highlighted the importance of a triad of factors – ‘drug’: the activity in question; ‘set’: the personal orientation of the individual involved with it, and, crucially, ‘setting’: the social, cultural and geograph-ical contexts – that behaviour went on in. Social sanctions, rituals and settings were crucial and, even in the case of reputedly ‘addictive’ drugs like heroin, he found that beginners had to actively ‘learn’ how to get high, usually through an intermediary who taught them the appropriate ways of interacting and responding to the drug. Such learning involved the transmission of information in which experienced users ‘introduced newcomers to the drug, provide[d] guidance...and

sooth[ed] the neophytes fears’ (p. 137).

In addition, little attention has focused on the micro-cultural milieux in which gambling goes on in. Here, the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of ‘cultural capital’ can be invoked to suggest ways in which apparently individual tastes might be products of wider social factors. Bourdieu (1984) argued that dispositions and tastes and competencies are not natural or inherent but are in fact ‘products of learning’ (p. 29) generated through social relations. His notion of cultural capital refers to the informal accumulation of such knowledge, which is embedded in particular configurations of class where it confers status and legitimacy on those who possess it, as well as distinguishing them from others who do not.

Accounts of beginning drug use have been influen-tial in advancing understanding of the social contexts and meanings of drug-taking behaviour, as has the notion of cultural capital in furthering understanding of the ways that different types of culture are legitimated (e.g. Thornton, 1995). However, similarly nuanced understandings have not been applied to gambling. Despite a considerable body of research, understand-ings of gambling tend to be framed predominantly in terms of individual and psycho-social deficits, with lack of competency in these areas invoked as expla-nations for behavioural problems (Reith, 2007).

As we have noted in the ‘Introduction’ section, few studies have considered the social context of early gambling behaviour in terms of its interactions with

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15

factors such as social and environmental networks, and with social class and gender. In particular, the ways that the behaviour and attitudes of wider social networks, as well as the general availability and acceptability of gambling within them, influence the initiation and development of gambling has not been fully explored. In addition, qualitative accounts of the meanings and motivations that are involved in these early experiences of gambling – of how and why individuals start to play and continue with their behaviour – are lacking.

Greater understanding of these issues is central to understanding why some individuals encounter and become involved in gambling at an early stage in the life cycle; why for some this encounter may become problematic, while for others, less so. It is with this in mind that the qualitative study presented here sets out to explore the broader social context of this crucial phase in individuals’ gambling careers from the point of view of players’ themselves.

AIMS AND METHODS

The research presented here is part of a larger longitudinal ESRC-funded study of ‘gambling careers’ designed to explore the social context of behaviour and the ways that it begins and changes over time. The study is based on a cohort of 50 recreational and problem gamblers interviewed three times between 2006 and 2009. Gamblers were recruited from around the greater Glasgow area, a large post-industrial conurbation in the West of Scotland, UK which is characterised by relatively high levels of unemploy-ment and pockets of social deprivation.

The overall aim of the research was to place problem gambling in its social context, examining it as a particular phase within broader ‘gambling careers’ which are embedded in social and geographical environments and which change over time. In this context, it focused on key stages of change, such as beginning gambling, moving towards and away from problematic behaviour, entering treatment and natural recovery. This initial piece of analysis focuses on the first stage of this process: beginning gambling.

Sample and recruitment

We recruited three main groups of individuals: problem gamblers in contact with treatment services (‘Group 1’ n¼12), problem gamblers not in contact with services

(‘Group 2’ n¼21) and regular/heavy recreational,

gamblers (‘Group 3’ n¼17). Problem players were defined as those scoring three or more on the NODS screen,1while recreational gamblers had to play at least once a week to be included in our sample. However, it is important to recognise that these were not entirely discrete groups, and that some participants moved from one group to another during the course of the study as behaviour became more or less problematic, or as individuals entered or left treatment. This will be

explored in further analysis, but for now we should note that when we talk of problem gambling or recreational gambling, this refers to a respondents’ status at the time of first interview.

In order to recruit our sample, and to ensure as much demographic diversity as possible within it, we adopted a bricolage approach, utilising a variety of recruitment techniques. We negotiated access to gambling venues from a major industry provider, and approached individuals in casinos, bingo halls and betting shops themselves. We also recruited individuals from a local counselling service and from Gamblers Anonymous, as well as advertising in a local newspaper and displaying posters in local community venues.

At the time of first interview, 23 respondents were considered to have or have had gambling problems, and 17 were classified as recreational players. The predominant games played were sports betting, bingo and machines (in bingo halls, arcades and betting shops). The majority of our sample is social class C2, D, E (lower class), which includes skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers, with the remainder A, B, C1, (higher class) which includes professionals, senior managers and top-level civil servants.2

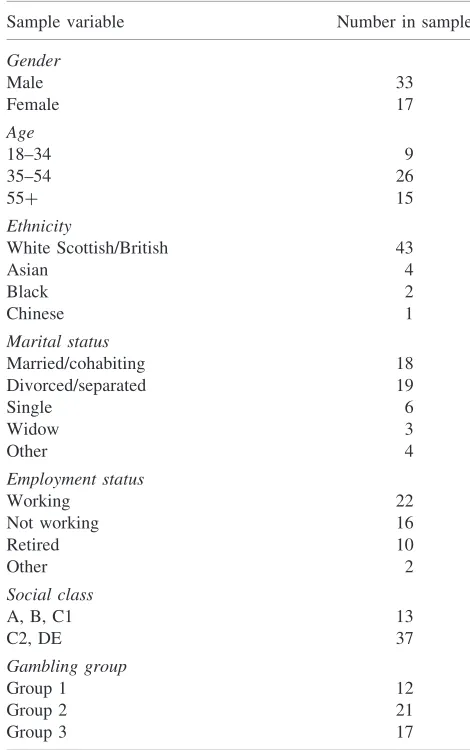

Table I. Overview of the sample.

Sample variable Number in sample

Gender

Male 33

Female 17

Age

18–34 9

35–54 26

55þ 15

Ethnicity

White Scottish/British 43

Asian 4

Black 2

Chinese 1

Marital status

Married/cohabiting 18

Divorced/separated 19

Single 6

Widow 3

Other 4

Employment status

Working 22

Not working 16

Retired 10

Other 2

Social class

A, B, C1 13

C2, DE 37

Gambling group

Group 1 12

Group 2 21

Group 3 17

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15

A profile of the 50 gamblers who took part in the study is shown in Table I.

Interviews and analysis

Interviews were carried out in various locations: most often respondents’ homes, but also within gambling venues and treatment centres. They were loosely structured by topic guides designed to cover a range of themes and drew on a ‘narrative’ approach, with the interviewer acting as a facilitator to tease out the factors that had influenced respondents gambling behaviour and the place that it had in their lives.

In the first of these interviews, respondents were encouraged to tell their ‘gambling story’: retrospective accounts of how they began to gamble and how their playing developed, including details on how they developed problems and/or controlled their play, recovery and experiences of treatment. Current behav-iour, attitudes and experiences were also explored.

Interviews were digitally recorded and later tran-scribed verbatim. Transcripts were analysed using ‘Framework’, a system of data management which allows for the rigorous analysis of qualitative data, developed by the National Centre for Social Research (Ritchie, 2003). Framework is a systematic and trans-parent method of analysis that ensures thorough and rigorous treatment of the data and reliability in interpreting findings. Using a matrix-based approach to analysis, it allows researchers to synthesise and condense transcripts; to treat cases consistently and allow within- and between-case investigation.

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore issues in depth within individual contexts rather than to generate data that can be analysed numerically. Thus, the sample was designed purposively to achieve range and diversity and was not intended to be representative of the wider gambling population. The aim of the interviewees was to go beyond the kind of information provided by numbers to explore meanings and themes in a series of rich narrative accounts. With this in mind, we deliberately avoid expressing findings in numerical terms (Kuzel, 1999).

RE SULTS

This article presents findings from the first phase of the research: ‘beginning gambling’, where we explore respondents’ accounts of their first memories and experiences of gambling. We should note from the outset that the focus of this article is not on the general development of a gambling career: i.e. the situations, triggers and events that influence the dynamic of individuals’ behaviour over time, which will be the topic of future analysis. The focus here is on the more limited period of respondents’ introduction to gambling and the social context of those early beginnings. That said, we did however begin to identify certain situa-tions that appeared to facilitate the development of gambling problems later in the life cycle; namely the

combination of starting gambling at an early age, within the family unit and among respondents of lower socio-economic status.

In most cases throughout this analysis, we are dealing with retrospective accounts of respondents’ childhoods and early years. Given the age profile of our sample, this means that accounts cover roughly the period late 1960s to early 1990s in which gambling in Britain was tightly regulated by the 1968 Gambling Act. This placed limits on types and availability of games, restricted access to venues and prohibited advertising. It has recently been superseded by the 2005 Gambling Act, implemented in 2007, which eases these restrictions and liberalises the market in this country.

Finally, a methodological point should be noted. Clearly, all research that is based on respondents’ recounting of past experiences suffers from issues relating to memory, bias, post-hoc rationalisation and the problems of corroboration. This is especially so if individuals are being asked to recall events from childhood. Although attempts were made to limit these shortcomings (including for example, checking for inconsistencies in interviews), such issues inevitably also apply to our research, and readers should bear this in mind when reading the accounts presented here. However, one thing that we found striking when analysing these narratives was the vividness with which many respondents described their early gam-bling experiences, and the seemingly effortless recall that illuminated these apparently significant moments in their lives. Although the processes involved in beginning gambling are often diverse, two key themes emerged as key across all accounts: the influence of the environment and of social networks. In addition, we found that these contexts influenced the development of problems later in life: Those who were introduced to gambling by their family – who also tended to be younger and belong to lower socio-economic groups – were more likely to develop problems later on, while those whose first experience of gambling was with colleagues or friends – who were also somewhat older and tended to belong to higher socio-economic groups – were less likely to have done so.

Throughout the discussion, details of respondents’ gender, age, socio-economic status and the group they were assigned to (1: problem gamblers receiving treatment, 2: problem gamblers not receiving treatment and 3: recreational gamblers) are given in parentheses after quotations.

Environment

Local geography features strongly in respondents’ accounts of early experiences, quite literally embed-ding gambling in local communities and neighbour-hoods. The geographical clustering of certain health behaviours such as smoking and drinking is well-established (MacIntyre, McIver, & Sooman, 1993), and research has also found that higher concentrations of

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15

gambling outlets as well as higher expenditure on games is correlated with low-income neighbourhoods (Livingstone, 2001; Welte, Wieczorek, Barnes, Tidwell, & Hoffman, 2004). Our study begins to show how these kinds of associations are experienced or ‘lived’ by respondents.

There is a traditionally high concentration of bingo halls and betting shops in lower socio-economic neighbourhoods in urban areas in Britain, which serve as social hubs for local residents (Dixey, 1996; Neal, 1998). In our study, these venues tend to be located on High Streets, close to bars, shops and fast food outlets where they can be dropped into on a regular basis as part of daily working, shopping and socialising routines. With venues that are easily accessible and which often serve as meeting places for locals, respondents were quite literally surrounded by gambling. Reflecting on the geographical and temporal ubiquity of gambling over the course of his life, one 50-year-old male voiced a situation that applied to most of our respondents, saying simply: ‘it was always something around me’ (M, 50, DE. Group 2).

It is not just physical availability that is important here, but also special knowledge of the settings where gambling goes on, available only to ‘insiders’, that is crucial. The following quote from a respondent recall-ing the era of illegal bookmakers and their ‘runners’ describes the awareness of the hidden networks of illegal betting spaces that only locals and insiders were privy to:

I lived in the XXX Road in XXX, that’s where I was brought up. Gambling was illegal then and bookmakers were illegal and they [bookies’ runners] stood in street corners and that’s how you got bets on and I knew they were there from a very, very young age.... Then there was other places around [the local area] that you could gamble, illegal bookmakers, different places, different points and I knew where they all were and I started to get interested in horses and my gambling started then. [M, 68, CD. Group 1]

This labyrinth of illegal gambling dens running throughout the local neighbourhood was invisible to outsiders, but provided an alternative, ‘underground’ geography to those who knew what to look for.

It is part of a wider geographical and cultural environment, in which heavy alcohol consumption is also common. It has frequently been noted that problem gambling occurs alongside problematic patterns of drinking (Feigelman, Wallisch, & Lesieur, 1998; Orford et al., 1996), and this inter-dependence features regularly in our respondents’ accounts of their gambling. However, we found the two behaviours connected to a third element: the broader socio-economic and cultural environment in which they are situated. Regular, heavy alcohol consumption is a habit that is integral to British working class male culture, and is also something that provides another public place – in the shape of

bars – where gambling can be carried out, in terms of playing card games and making private bets as well as discussing the results of games and spending winnings. This relationship was articulated by one respondent who explained:

In the West of Scotland you’re brought up in a gambling and a drinking environment and I when I was young I drunk as well [as gambled] from an early age. [M, 51, C2. Group 1]

In addition, public bars and betting shops are frequently located next door to one another in towns, providing easy access from one to the other. One male provided an evocative account of the physical inter-relation of gambling and alcohol, describing the proximity of both types of venues to his home:

I lived above the bookmakers...there’s a pub called the Horse and Barge and there’s a betting shop right next to it; well I lived on the first floor. This would be the pub [points down] and that would be my living room there [points directly above] so all that was missing was the fireman’s pole to slide me in. [M, 43, DE. Group 2]

Social networks

Within these gambling spaces, respondents learned to gamble through social networks. This process involves the acquisition and transmission of a form of gambling-specific knowledge, attitudes and behaviour: what the sociologist Bourdieu (1984) might describe as ‘cultural capital’. In our study, we saw the reproduction of certain kinds of knowledge, or gambling-related ‘cul-tural capital’, from an early age. It occurred through the transmission of knowledge about the (often quite complex) language, rules and rituals involved in the gambling. In order to take part in many types of games, it is necessary to understand at least some often quite specialised terminology: for example, the workings of ‘accumulators’, ‘lines’ ‘place’ and ‘each way’ bets; the specific rituals involved in placing bets and collecting winnings, as well as the complex calculation of odds and probabilities. As we saw in the previous section, it is not only necessary to know where gambling takes place; to take part in games of chance it is also necessary to be aware of the sometimes arcane social rituals and etiquette that govern the activity. Not handing cash directly to cashiers, monitoring nods and eye contact to control the flow of chips in a casino, avoiding specific seats reserved for regulars in bingo halls, knowing where to cash out tokens in the ‘puggy’ (fruit machine) arcade – all are crucial social rituals that govern involvement in games of chance. All of this has to be learned, and for the individuals in this study, such knowledge was passed on through relationships with family, friends and colleagues.

The remainder of this section includes discussion of these three key social groups – family, friends and colleagues – and their inter-relationship with age, social class and the development of gambling problems later in life. Overall, we found that those whose first

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15

experience of gambling was facilitated within the family tended to be younger than those whose first experience was with friends or colleagues, with an age range between 5 and 22 years, and some clustering around age 8–12. They also tended to be made up of individuals from lower socio-economic groups; i.e. C2, DE. In addition, those who were introduced to gam-bling by their family were also more likely to develop problems later in life, while those whose first experi-ence of gambling was with colleagues or friends were less likely to have done so. In contrast, those who started playing with friends and colleagues tended to start at a later stage than those who first gambled in family networks, with average ages ranging from late teens and early twenties to thirties. They were also slightly more likely to belong to higher social classes and to be members of ethnic minority groups.3 In addition, they were less likely to have developed gambling problems later in their gambling careers.

Family

Interviews revealed the importance of the family, and particularly the working class family, as a key site for the transmission of gambling related cultural capital and for the reproduction of behaviour, norms and attitudes. We found a process whereby gambling knowledge and behaviour was passed on through households in the routines of everyday life. It is a pattern in which respondents’ parents regularly visited gambling venues and participated in games, so that participants themselves were surrounded by an envi-ronment where gambling was normal, acceptable, enjoyable and fun – or, on the other hand, could also be the source of arguments, tension and worry, which as children, they absorbed. Awareness of gambling was generated through observation of other people’s behav-iour, where respondents watched and heard family members doing and talking about their gambling, and sometimes joined in with it.

This reproduction of behaviour and attitudes involves a ‘generational transmission’ of cultural capital from parents and grandparents to children. As one said: ‘my father gambled, and he passed it on to all of us’ [M, 54, DE. Group 1]. From a bio-medical perspective, this inheritance could be taken to imply a transmission of genetic information. However, we can see that in this context, it refers to socio-cultural conditions, and the passage of cultural capital – of competencies, habits and norms – which, as Bourdieu (1984) would put it, is passed through the generations: ‘hand[ed] down to...offspring as if in an heirloom’ (p. 66).

Encounters with gambling were transmitted through families in gendered ways. A common pattern was for female respondents to become aware, and often have their first experience of, gambling, through their mothers; males through their fathers – or, to a lesser extent, through other family members of the same gender: women through aunts, sisters and grand-mothers; men through uncles, brothers and

grandfathers. The games that respondents were intro-duced to in this way were also gendered, with women introduced mainly to bingo and machines, men to sports betting.

For example, a female respondent had been aware of gambling: ‘from as far back as I can remember’, ‘about ten, eleven...[when] I was younger and my mum used

to go to the bingo’ [F, 29, C2. Group 2]. She remembered going to meet her mother at the local bingo hall twice a week, standing outside and hearing the caller, and enjoying the atmosphere around the venue. She absorbed the atmosphere and camaraderie of the adult world around the bingo hall, and was aware of its sociable aspect from an early age:

You used to see her [her mother] coming out of the bingo and she used to have a carry on [a laugh] with the staff.... I think it was just standing outside, hearing the caller and things like that, that I just...it was quite...it was the atmosphere of the people coming out as well do you know what I mean, it looked quite enjoyable and that’s when I just thought ‘I’ll give it a go’. [F, 29, C2. Group 2]

For males, similar processes of transmission occurred. A common pattern involved fathers intro-ducing their sons to sports betting, especially horse race betting, both in the home on television and outside in betting shops. For example, one respondent described watching televised wrestling on Saturday afternoons, wagering biscuits with his father on the winner. He also recalled: ‘I always remember sitting on my grandfather’s knee and he would put on a line [on the Grand National]’ [M, 72, DE. Group 1]. This is the inheritance of cultural capital, passed down the gener-ations through biscuits and bets.

Families actively facilitated many of our respon-dents’ gambling in various ways: for example, by asking children (especially boys) to take their bets to the betting shop for them; helping them to pick numbers, horses or teams for sports betting, and by giving them money to gamble with. For some respon-dents, putting on the family ‘lines’ (bets) was part of their daily chores along with tasks such as going to the local shop for groceries. For example, one male’s first experiences of gambling were actively facilitated by his family when he was asked to take the family bets to the betting shop for them:

I used to take the family lines to the street bookie and he used to give all the kids that took the lines an old penny...That’s when my gambling started [aged six]: I would have a bet with the penny...it was fun in those days and I always thought I could win. [M, 50, C1. Group 1]

His mother continued to facilitate his interest in gambling by writing him sick notes to stay off school when racing was broadcast on television. He recalls that it was fun at the time, and his mother never considered it harmful. He developed a serious problem later on, however, gambling on sports and in casinos.

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15

Another account describes what appears as almost a rite of passage in which a respondent was initiated into an adult, masculine world through the betting shop and the bar:

I can remember the first time that I really won any money, I was in the betting shop in X, I think I won £85 and I probably wasn’t eighteen....[the legal age for gambling] [so] I ran all the way along the road [to my grandfather’s house]... I’ll never forget it,....he was sound asleep, I said, ‘Grandda, I’ve won £85,’ and he just slid into his shoes and put his jacket on,...and he says to me, ‘I’ll show you what to do with the money, boy’, he says, ‘you look after your enemies because your friends will never do you any harm’. And he took me to the pub....and he told me to buy this one [man] and that one a drink and he was kinda teaching me about the people who will loan you money when you’re skint,...It was exciting, getting in the company, and I loved that day and he took me back to stay with him that night...so it was quite an exciting day and I think that’s what I chased forever, days like that to come back you know, just feel as if you were...I felt important. [M, 43, DE. Group 1]

In this narrative, we can see the development of positive associations of gambling for this individual, and his process of ‘becoming’ a gambler through the learning of new roles and social practices. As Becker (1963) pointed out, the role of experienced users (in our case, gamblers) can be crucial in converting an experience into something meaningful ‘who in a number of ways teach the novice to find pleasure in this experience’ (p. 54). This respondent’s grandfather provided approval and articulated the positive mean-ings of games, so that winning money became trans-lated into gaining respect and initiation into an adult, masculine world. For this player, the game itself became associated with self-worth and status central to the creation of a ‘gambling’ identity. Not only was a family member integral to the process of playing, he was also part of the pivotal moment in ‘becoming’ a gambler: in creating a feeling and a situation that the respondent spent the rest of his life chasing.

Friends

The category of ‘friends’ can include a variety of social networks (Spencer & Pahl, 2006). Some friends are childhood companions, and these are often inter-linked with family and neighbourhood networks, while others involve relationships made later in the life cycle, when individuals leave school and the family home and move away to further education or work.

In some cases, a close link between the gambling that went on in the family and gambling with friends existed. For example, family and friends are inter-dependent in one respondent’s account of the first time he bet for himself. Although he had been around gambling all his life – ‘Grew up with it and watched my father.... It wasn’t anything new’ – he was

indifferent to it. He regularly accompanied friends to the betting shop, but did not place bets. However, one day they were late and to fill time he placed a bet for

the first time. He won a lot of money, describing his response as: ‘Ecstatic!’. This response was encouraged by his social network:

My mates couldn’t believe that I had actually put a bet on in the first place never mind won it. And the more they patted me on the back...it bums you up [encourages you] and...the first thing I did was....take my mother and my two sisters out that night. [M, 42, DE. Group 2]

In this example, friends were not directly involved in the respondents’ first gambling attempt, but their reaction to it was what encouraged him to continue. As well as money, the rewards of winning included esteem and respect, which was conferred on the player by the congratulations of his peer group, as well as an opportunity to demonstrate status by treating female relatives with his winnings. Their congratulations and encouragement were crucial, and evoke a rite of passage: the respondent had finally joined them in their activity. More than the acquisition of technical knowledge and skills, however, this player had to learn how to actually enjoy gambling in its own right. An analogy can be drawn with learning to enjoy drugs. Becker (1963) points out that marihuana users often failed to get high the first few times they consumed drugs, and thus did not ‘form a conception [of the drug] as something that can be used for pleasure’ (p. 48). Similarly, this individual had never personally experi-enced the pleasures of gambling, having never played (and therefore never won) for himself. Now that he had, however, his whole perception of the activity changed. Looking back on the episode, he told us: ‘I think that set me on the road to being a gambler’.

In slightly older friendship networks, we often found starting to play tied up with increasing independence, moving away from the family unit, starting employ-ment, developing new friendship networks and estab-lishing work-based roles and identities. This applied particularly to males, for whom the temporal rhythms and spaces of work appeared to interact with the primarily masculine gambling settings of betting shops and race tracks.

One respondent first started gambling when he began an apprenticeship at the age of 17 and became friendly with a workmate who was a heavy gambler. This friend introduced him to dog racing, and he started going to the racetrack four nights a week. Here, the colleague/friend division is blurred, but again, begin-ning gambling is tied up with learbegin-ning complex social rituals and behaviour as well as learning to derive enjoyment from them:

I left school and went to work, I didn’t gamble at school I suppose I didn’t have the money. When I went to work I got friendly with my pal and he was a great gambler and he started going to the dogs, dog racing at night, that’s really when I started gambling....I enjoyed the atmosphere and I enjoyed the excitement. I never won as much as my wee pal; he was a real, real gambler.... But it was exciting, even if you got beat

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15

you still got a kick...I used to go four nights a week, to the dog racing. He got me into it. [M, 60, C1. Group 3]

Having money from a job, as well as being friends with someone who already went to racetracks and could show him how to place bets, are central here. The excitement and atmosphere of the activity are more important than winning – ‘even if you got beat you still got a kick’ – and this is what kept him going back. This respondent remained a controlled player all his life, gambling regularly but recreationally on horse races and football pools.

Colleagues

Respondents who had their first experience of gam-bling with individuals they specifically identified as colleagues tended to be in their late teens to thirties, and were also more likely to be higher social class. Significantly, here gambling appears to be interwoven with the temporal routines and schedules of work, as well as with the social networks that employment creates.

One recreational gambler who currently gambles regularly on sports and in casinos had his first bet with workmates when he was 19. He worked upstairs from a betting shop, and put on a sweepstake with colleagues, before going to the bar next door:

The first real time I ever had a bet would be when I was working up the town for this Firm and there was a wee bookies down the stairs actually inside the building. We were in an office and about a dozen of us I think, we all went down to this place and put our bets on and we had a sweepstake upstairs, and then we all retired to what was the Empire Bar round in X Street [for a drink]. I can remember that well. [M, 64, C1. Group 3]

Here, the proximity of the betting shop and bar with the workplace mirrors the situation we saw in the earlier section on family, where gambling venues, bars and homes were embedded in local communities. Similarly, it is this environmental context that contrib-utes to the accessibility of gambling for this individual. For others, the routine of work is something that gambling activity fits around, in terms of both temporal breaks, and the proximity of gambling venues to work ones.

This was particularly noticeable among our ethnic minority gamblers, many of whom had their first experience of gambling with colleagues, often for example, visiting casinos after working shifts. A Chinese player, for example, first gambled with colleagues after work when he was in his forties. He explained that after finishing a shift, it would be too early to go to bed, but nowhere was open and so he, along with others who worked in the restaurant trade, would visit one of the nearby city-centre casinos to meet friends, have some food or win money – ‘maybe get lucky’. He has followed this routine for over 20 years, visiting the casino two or three times a week

and making small bets without experiencing any problems [M, 70, C1. Group 3].

A similar pattern of introduction, whereby gambling is interwoven with patterns of work and socialising, can be seen with a 61-year-old male who first gambled with a colleague when he moved to Britain from North Africa in his twenties. His colleague showed him how and where to play:

During the lunchtime we would go and have something to eat and on the way back he would go into this [betting] shop and place a bet.... [M, 61, AB. Group 3]

They lived close to each other, which encouraged them to spend time together around betting:

I had a flat and his flat was facing mine. So after we were going home, we would go into this [betting] shop and...I said how do you do that? So he said to me you just look at the board [where odds and results are displayed] and pick a horse and if it wins you get paid. I said, just as easy as that? He said yes. And well...that’s how I placed my first bet.

In this narrative, we can see the significance of the colleague who taught the respondent how to play. Also important is location: both the proximity of the betting shop to the workplace, as well as the respondent’s home to his colleague’s home.

In all of our examples where respondents had their first experience of gambling with colleagues, we found that the activity was woven around the temporal patterns of employment, in terms of breaks and routines, as well as the physical location of gambling and work venues. Both these work-related aspects are in turn connected to patterns of socialising and friendship that revolve around employment itself.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

Contrary to research which has focused on the psychological and individual determinants of gambling behaviour, this study shows up the fundamentally social nature of the activity. It shows that respondents are not born gamblers, but rather ‘become’ gamblers through complex processes of observation, facilitation and learning. Significantly, our respondents are all introduced to the world of gambling through their social networks. They do not ‘fall upon’ gambling in isolation, but grow up surrounded by it and learn it through networks of social interaction, which are in turn rooted in particular social, cultural and geographical environments.

Gambling is an activity imbued with cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1984) that is actively learned and reproduced through relationships between gamblers, their social networks and wider environmental settings. In particular, the family is a key site of social reproduction where many individuals encounter games of chance for the first time. This is where they become familiar with the mechanics as well as the social rituals and etiquette of games; familiarity that is passed down

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15

through generations of families ‘as an inheritance’. In our study, this inheritance of dispositions and competencies applies particularly strongly to respon-dents from lower socio-economic groups.

The family is also a common site for the develop-ment of gambling problems. When family relations, rather than friends or colleagues, are the primary facilitators of gambling involvement at an early age, individuals are more likely to develop gambling problems in later life. However, this does not imply that the relationship between the family as a site of early gambling behaviour and the development of problem gambling in later life is necessarily straight-forward or linear. As we have seen, other factors are involved here, including age and social class, with individuals who began gambling in family environ-ments also tending to be younger and of lower socio-economic status than those who did not.

More than simply encountering games of chance, individuals must also actively learn to partic-ipate in and – crucially – attribute meaning to and derive pleasure from them. More experienced players guide novices through this process, teaching them how to play and showing them (often through example) the rewards and pleasures of games. Family networks are again central to this ‘sequence of social experiences’ (Becker, 1953, p. 235), although friends and colleagues also play an important role, particularly among respondents from higher socio-economic groups. In many narratives, beginning gambling appeared as a rite of passage through which individuals were initiated into the adult, gendered social worlds of betting and bingo. For others, it was associated with increasing independence and the development of friendship networks and work-based roles and identities.

As well as the intrinsic rewards of games them-selves – which include, among other things, winning money, excitement and social status – it is apparent that the setting of games is crucial, and that gambling is interdependent with the social environment (Zinberg, 1984). The ‘place’ of gambling in many individuals’ lives is in many cases quite literal. Gambling venues are interspersed throughout local communities and woven into the fabric of everyday life as part of wider patterns of living, working and socialising. Both public and private spaces – from gambling venues themselves to workplaces, homes and bars – are crucial arenas within which gambling is encountered and learned. However, the importance of place extends beyond the simple accessibility of gambling opportunities – although these are important – to encompass the ways that locations interweave with social relations and the daily routines and cultures that are created around them. It is not enough that gambling opportunities are simply ‘there’: social relationships are the crucial conduit through which they are endowed with mean-ing and made to matter to the individuals who encounter them.

We are aware that, to some extent, the patterns we have identified here are reflective of the age and social class of our sample. We are also aware that, given the age of many of our respondents and the retrospective, longitudinal aspect of this research, the narratives of gambling that we have presented here cover a period from the late 1960s to the mid-1990s, which represents a different policy climate to what exists today. This period of gambling in Britain was given its distinctive character by the 1968 Gambling Act which restricted the availability and promotion of commercial gambling with its principle of ‘unstimulated demand’. This has recently been superseded by the 2005 Gambling Act which was implemented in 2007. This legislation heralds an era of increased liberalisation in Britain, including easier access to a range of gambling oppor-tunities and the increasing normalisation of the activity. Advertising is now permitted and gambling operators are able to promote themselves as commercial prem-ises, and are seeking to attract new demographic groups, particularly women and higher socio-economic groups. In addition, new types of games (such as a national Lottery) and new mediums for gambling (such as the Internet and mobile phone technology) have appeared in recent years. This changing climate raises the question of whether we might expect to see a corresponding shift in early experiences of gambling. Indeed, there is some evidence of this already, with recent research finding that young people gamble on, for example, lottery products (Moodie & Finnegan, 2006; Wood & Griffiths, 1998), which were not available to most of our generation of respondents.

Meanwhile, some commentators have recently argued that an increasingly globalised, de-centred gambling environment has emerged as new forms of technology break down geographical barriers, driving increasingly homogenous commercial gambling prod-ucts around the globe. As one writer put it: ‘gambling is no longer a social activity shaped primarily by community needs and values’ (McMillen, 1996, p. 11). From the evidence presented here however, we would argue that while it is undoubtedly true that such trends have revolutionised the way gamblers access and even experience games of chance, this does not mean that local environment and context have become redundant. While we might expect to see the impact of policy changes as well as commercial and technolog-ical developments over the coming years, we find no reason to assume that the role of the broad social relationships identified in this research will not continue to be anything other than crucial in mediating the ways that individuals begin gambling.

Indeed, our study emphasises the continued embeddedness of gambling in physical places and social relations. Games may be commercial products, supplied by global organisations and driven by tech-nological innovation, but they are experienced and played within terrestrial, social environments, in which they are also given meaning. What we have found is

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15

gambling that is inextricably linked to local commu-nities, neighbourhoods and practices through a range of inter-personal social relationships.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and the Responsibility in Gambling Trust (Ref No: ESRC RES 164-5). We are grateful to all the gamblers who gave up their time to speak with us for the study, and to Anne Birch, Irene Miller and Fiona Rait at the Scottish Centre for Social Centre Research for conducting some of the interviews on which it is based. Special thanks go to Lesley Birse for formatting the paper and to Simon Anderson for commenting on earlier versions of the draft manuscript.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

NOTES

1. This was developed in the late 1990s for the National Gambling Impact Study Commission primarily for use in large scale surveys. It is based closely on the DSM-IV screen and had been used in prevalence studies, mainly in the United States (Gerstein et al., 1999). We used the NODS-CLiP to recruit our sample, and among those participants who were selected to take part in the study, the full NODS screen was administered. This allowed us to classify players into problem and non-problem groups.

2. Social class was measured using the NRS Social Grades. They were originally developed over 50 years ago for the National Readership Survey but are now widely used across the United Kingdom. http://www.nrs.co.uk/lifestyle.html

3. Despite being small in number, most of our respondents from an ethic background tended to have their first experience of gambling out with the family.

RE FERE NCE S

Abbott, M.W. (2001). Problem and non-problem gamblers in New Zealand: A report on phase two of the 1999 National Prevalence Survey. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs.

Abbott, M.W., & Volberg, R.A. (2000). Taking the pulse on gambling and problem gambling in New Zealand: Phase one of the 1999 National Prevalence Survey. Report number three of the New Zealand Gaming Survey. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs.

Becker, H. (1953). Becoming a marihuana user. American Journal of Sociology, 59, 235–242.

Becker, H. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: Free Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. London: Routledge.

Derevensky, J., & Gupta, R. (Eds.). (2004).Gambling problems in youth: Theoretical and applied perspectives. New York: Kluwer Academic.

Derevensky, J., & Gupta, R. (2007). Adolescent gambling: Current knowledge, myths, assessment strategies and public policy implications. In G. Smith, D. Hodgins, & R. Williams (Eds.),Research and measurement issues in gambling studies

(pp. 437–463). New York: Elsevier.

Dixey, R. (1996). Bingo in Britain: An analysis of gender and class. In J. McMillen (Ed.), Gambling cultures. London: Routledge.

Feigelman, W., Wallisch, L.S., & Lesieur, H.R. (1998). Problem gamblers, problem substance users, and dual problem individuals: An epidemiological study.American Journal of Public Health, 88, 467–470.

Fisher, S. (1993). The pull of the fruit machine: A sociological typology of young players.Sociological Review, 41, 446–474. Fisher, S. (1999). A prevalence study of gambling and problem

gambling adolescents.Addiction Research,7, 509–538. Gerstein, D.R., Volberg, R.A., Toce, M.T., Harwood, H.,

Palmer, A., Johnson, R.,..., Hill, M.A. (1999). Gambling

impact and behavior study: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission. Chicago, IL: National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago.

Griffiths, M. (1995).Adolescent gambling. London: Routledge. Gupta, R., & Derevensky, J. (2008). Gambling practices among youth: Etiology, prevention and treatment. In C.A. Essau (Ed.), Adolescent addiction: Epidemiology assessment and treatment(pp. 207–230). London: Elsevier.

Huxley, J., & Carroll, D. (1992). A survey of fruit machine gambling in adolescence. Journal of Gambling Studies, 8, 167–179.

Jacobs, D.F. (2000). Juvenile gambling in North America: An analysis of long term trends and future prospects.Journal of Gambling Studies, 16, 119–152.

Jacobs, D.R., Marston, A.R., Singer, R.D., Widaman, K., Little, T., & Veizades, J. (1989). Children of problem gamblers. Journal of Gambling Behaviour, 5, 261–267.

Kalischuk, R.G., Nowatzki, N., Cardwell, K, Klein, K., & Solowoniuk, J. (2006). Problem gambling and its impact on families: A literature review.International Gambling Studies, 6, 31–61.

Kuzel, A. (1999). Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In B. Crabtree & W. Miller (Eds.),Doing qualitative research(pp. 33–45). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Livingstone, C. (2001). The social economy of poker machines.

International Gambling Studies, 1, 12–45.

MacIntyre, S., McIver, S., & Sooman, A. (1993). Area, class and health: Should we be focusing on people or places?Journal of Social Policy, 22, 213–234.

McMillen, J. (1996). The globalisation of gambling: Implications for Australia. The National Association for Gambling Studies Journal, 8, 9–19.

Moodie, C., & Finnegan, F. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of youth gambling in Scotland.Addiction Research and Theory, 14, 365–385.

Neal, M. (1998). ‘‘You lucky punters!’’ a study of gambling in betting shops.Sociology, 32, 581–600.

Orford, J., Morrison, V., & Somers, M. (1996). Drinking and gambling: A comparison with implications for theories of addiction.Drug and Alcohol Review, 15, 47–56.

Orford, J., Sproston, K., Erens, B., White, C., & Mitchell, L. (2003). Gambling and problem gambling in Britain. Hove: Brunner-Routledge.

Raylu, N., & Oei, T.P.S. (2002). Pathological gambling: A comprehensive review. Clinical Psychology Review, 22, 1009–1061.

Reith, G. (2007). Situating gambling studies. In G. Smith, D. Hodgins, & R. Williams (Eds.),Research and measure-ment issues in gambling studies (pp. 3–29). New York: Elsevier.

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15

Ritchie, J. (2003). Carrying out qualitative analysis. In J. Ritchie & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage. Shaffer, H.J., LaBrie, R.A., LaPlante, D.A., Nelson, S.E., &

Stanton, M.V. (2004). The road less travelled: Moving from distribution to determinants in the study of gambling epidemiology.Canadian Journal of Psychiatry,49, 504–516. Thornton, S. (1995). Club cultures: Music, media and

sub-cultural capital. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Spencer, L., & Pahl, R. (2006).Rethinking friendship: Hidden solidarities today. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Volberg, R.A. (2001). When the chips are down: Problem gambling in America. New York, NY: The Century Foundation.

Walters, G.D. (2001). Behavior genetic research on gambling and problem gambling: A preliminary meta-analysis of available data.Journal of Gambling Studies, 17, 255–271. Wardle, H., Sproston, K., Orford, J., Erens, B., Griffiths, M.,

Constantine, R., & Pigott, S. (2007). British Gambling Prevalence Survey. London: National Centre for Social Research.

Welte, J., Wieczorek, W., Barnes, G.M., Tidwell, M.-C., & Hoffman, J.H. (2004). The relationship of ecological and geographic factors to gambling behavior and pathology.

Journal of Gambling Studies, 20, 405–423.

White, C., Mitchell, L., & Orford, J. (2000).Exploring gambling behaviour in depth: A qualitative study. London: National Centre for Social Research.

Wood, R., & Griffiths, M. (1998). The acquisition, development and maintenance of lottery and scratchcard gambling in adolescence.Journal of Adolescence, 21, 265–273.

Zinberg, N. (1984). Drug, set, and setting: The basis for controlled intoxicant use. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Zinberg, N., & Shaffer, H. (1985). The social psychology of intoxicant use: The interaction of personality and social setting. In H.B. Milkman & H. Shaffer (Eds.),The addictions: Multidisciplinary perspectives and treatments. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Zinberg, N., & Shaffer, H. (1990). Essential factors of a rational policy on intoxicant use.Journal of Drug Issues, 20, 619–627.

Addict Res Theory Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by University of Glasgow on 02/27/15