HIMPSI

J U R N A L

P S I K O L O G I

I N D O N E S I A

ISSN: 0853-3098 2017, Juni, Vol XII, No 1, h. 1-117 • CONTRIBUTING FACTORS TO PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS IN PORNOGRAPHYUSERS’ WIVES (h. 1-18) Inez Kristanti and Dinastuti

Faculty of Psychology, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia

• ‘AKTIF’ TEACHER TRAINING PROGRAM TO INCREASE TEACHERS’ SELF EFFICACY IN TEACHING CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS (h. 19-30)

Amitya Kumara, Dian Mufitasari, Krysna Yudy Nusantari, and Iga Serpianing Aroma

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

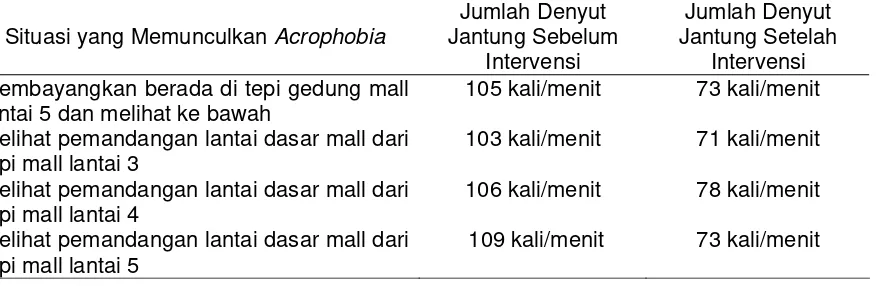

• EFEKTIVITAS COGNITIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY UNTUK DEWASA MUDA DENGAN ACROPHOBIA (h. 31- 40)

Garvin

Universitas Bunda Mulia

Monty Satiadarma dan Denrich Suryadi

Universitas Tarumanagara

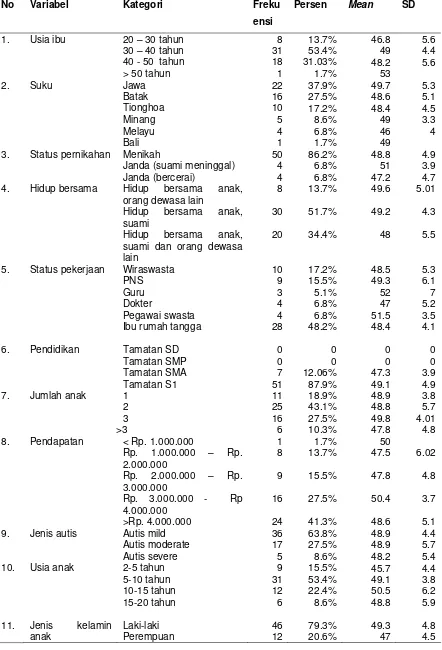

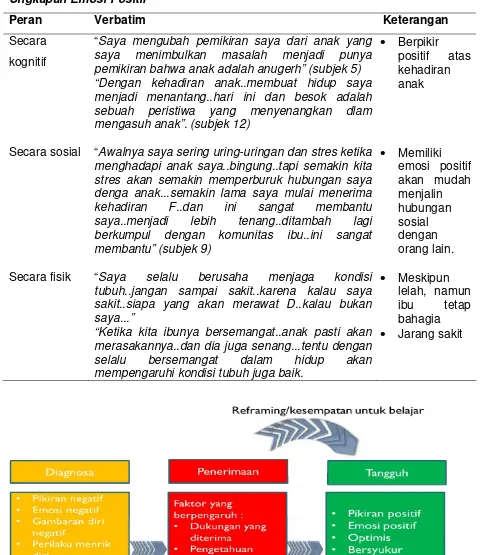

• EMOSI POSITIF PADA IBU YANG MEMILIKI ANAK DENGAN GANGGUAN SPEKTRUM AUTIS (h. 41- 62)

Nurussakinah Daulay

Universitas Islam Negeri Sumatera Utara

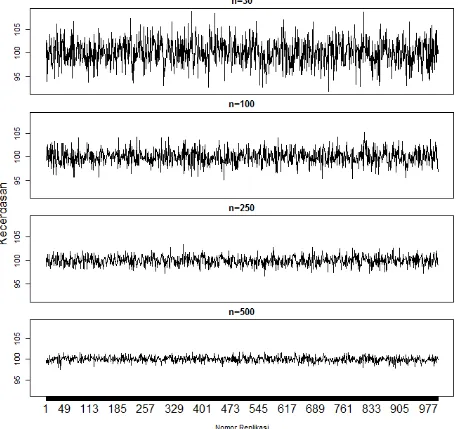

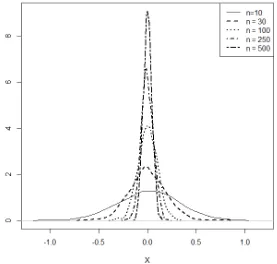

• BENARKAH UKURAN SAMPEL MINIMAL = 30 ? (h. 63-84) Agung Santoso

Universitas Sanata Dharma

• PRAKTEK KESELAMATAN KERJA DITINJAU DARI SUDUT PANDANG KARYAWAN (h. 85-104)

Raden Siti Ayunda Nurita dan Rayini Dahesihsari

Magister Psikologi Profesi, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya

• ART THERAPY BERBASIS CBT UNTUK MENURUNKAN AGRESIVITAS ANAK KORBAN KEKERASAN DALAM RUMAH TANGGA (h. 105-117)

Yustisia Anugrah Septiani dan Maria Goretti Adiyanti

JURNAL PSIKOLOGI INDONESIA

Pemimpin Redaksi/Penanggung Jawab

Ketua Umum Himpunan Psikologi Indonesia

Ketua Dewan Redaksi

Dr. Tjipto Susana, M.Si., Psikolog

Sekretaris Dewan Redaksi

Juneman Abraham, S.Psi., M.Si.

Anggota Dewan Redaksi

Prof. Dr. Faturochman, M.A. Prof. A Supratiknya, Ph.D., Psikolog

Dr. Moordiningsih, M.Si., Psikolog J. Seno Aditya Utama, S.Psi., M.Si.

Mitra Bestari FENDY SUHARIADI

HERA LESTARI

Penerbit

Himpunan Psikologi Indonesia

Alamat Redaksi

Sekretariat Himpunan Psikologi Indonesia Jl. Kebayoran Baru No. 85 B, Kebayoran Lama, Velbak

Jakarta 12240 Telp/Fax: 021-72801625 Situs web: http://jurnal.himpsi.or.id ;

https://independentscholar.academia.edu/JurnalPsikologiIndonesia Surat elektronik: jpi_himpsi@yahoo.com

Media Sosial: http://twitter.com/himpsipusat ; http://instagram.com/himpsipusat http://facebook.com/himpsi H

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS 1

Jurnal Psikologi Indonesia Himpunan Psikologi Indonesia

2017, Vol. XII, No. 1, 1-18, ISSN. 0853-3098

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS TO

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS IN

PORNOGRAPHY USERS’ WIVES

(FAKTOR-FAKTOR PENDUKUNG

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS PADA ISTRI

PENGGUNA PORNOGRAFI

)

Inez Kristanti

and

Dinastuti

Faculty of Psychology, Atma Jaya Catholic University of Indonesia

Some women react negatively to their husbands’ habit of using pornographic materials and this reaction is called pornography distress which can potentially bring damage to a marriage such as lowering the quality of sexual activities and marital satisfaction. To help solve the issue, the differentiating factors between women who experienced pornography distress and those who did not were identified. Seven contributing factors to pornography distress were proposed: perceived frequency of husband’s pornography use, the duration of knowledge about husband’s pornography use, the way of knowing about husband’s pornography use, attitude towards pornography use, and exposure to sexual content from the media, religious salience, and differentiation of self. This research aimed to discuss factors that significantly contribute to pornography distress. Data from 161 women who are married to pornography users were obtained through accidental sampling. All participants were currently residing in Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, or Bekasi. Multiple linear regression analysis found four significant contributing factors: the way the subjects found out about their husbands’ pornography use, attitude towards pornography, religious salience, and differentiation of self. Results showed that contributing factors to pornography distress came from various sources. Each spouse should work together to achieve some sort of agreement and understanding to solve pornography distress issues. Several suggestions regarding the issue are discussed.

Keywords: marriage, pornography, pornography distress, sexuality, wives

Sebagian perempuan menunjukkan reaksi negatif terhadap kebiasaan suami menggunakan pornografi. Reaksi ini disebut sebagai pornography distress. Pornography distress dapat mendatangkan dampak buruk dalam pernikahan, misalnya menurunkan kualitas hubungan seksual dan kepuasan pernikahan. Untungnya, tidak semua perempuan menunjukkan tanda-tanda pornography distress. Untuk membantu penyelesaian masalah ini, faktor yang membedakan antara perempuan yang mengalami dan tidak mengalami pornography distress perlu diidentifikasi. Terdapat tujuh faktor yang diduga berkontribusi terhadap pornography distress; persepsi tentang frekuensi penggunaan pornografi suami, lama mengetahui penggunaan pornografi suami, cara mengetahui penggunaan pornografi suami, sikap terhadap pornografi secara umum, keterapaparan terhadap konten seksual dalam media, religious salience, dan diferensiasi diri. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk menemukan faktor-faktor yang berkontribusi secara signifikan terhadap pornography distress. Data dari 161 istri pengguna pornografi diperoleh dengan accidental sampling. Semua partisipan tinggal di Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, atau Bekasi pada saat pengambilan data. Analisis menggunakan multiple linear regression menunjukkan adanya empat faktor yang berkontribusi secara sgnifikan: cara mengetahui penggunaan pornografi suami, sikap terhadap pornografi, religious salience, dan diferensiasi diri. Hasil

2 KRISTANTI & DINASTUTI

penelitian ini menunjukkan bahwa faktor yang berkontribusi terhadap pornography distress datang dari sumber yang beragam. Oleh karena itu, masing-masing pihak dalam pernikahan perlu bekerjasama untuk memperoleh kesepakatan dan pemahaman satu sama lain yang dapat menyelesaikan masalah pornography distress. Beberapa langkah praktis akan didiskusikan dalam artikel ini.

Kata kunci: pernikahan, pornography, pornography distress, seksualitas, istri

Pornography is “any sexually oriented material that is created simply for the purpose of arousing viewer” (Carroll, 2010). Pornography materials are easily accessed from almost all kinds of media-internet, in particular (Copper et al., as cited in Stewart & Szymanski, 2012; P.M. Markey & Markey, 2012). It is hard to tell the exact number of pornography users in Indonesia, however most people agree that this country shows high usage of pornography materials, occupying first to fifth rank in the world (“Kominfo sebut”, 2012; Olivia, 2013; Pitoyo, 2012; Suryanto, 2009).

Research on pornography in Indonesia is largely emphasized on teenage population (Ramadhan, 2013; Roviana, 2011; “Sebagian besar”, 2013), when there are plenty of married individuals actively seeking pleasure from pornography materials. A pilot study conducted to 98 married individuals in Jabodetabek (an acronym referring to five big cities in West Java: Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, Bekasi) shows that 81.63% of them uses pornography. Thirty percent of them uses pornography once to seven times a week. Large proportion (83.33%) of married women admit the tendency to use pornography with their partners while more men (56.82%) prefer to do it alone. Men tend to use pornography as a mean to achieve sexual pleasure without their

partners while women tend to use it to elevate sexual pleasure before having sexual intercourse. These findings are consistent with Hald (as cited in Carroll, 2010) and Strager (2003) that most of men use pornography to achieve sexual pleasure, by masturbating.

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS 3

their partners. They tend to view their partners as perverts or sex addicts. Men’s pornography use might also affect their partners’ view on their relationships. Women in these relationships tend to feel betrayed, as if their partners have “cheated”. Bridges, et al. (2003) summed up these negative responses with one term: pornography distress, or negative experience/condition that is felt by an individual as a response to her partner’s pornography use.

These findings by Bergner and Bridges (2002) serve as empirical evidence that women might be significantly affected by their partners’ pornography use. Meanwhile, men’s pornography use is proved to correlate significantly with the overall relationship satisfaction (Poulsen, Busby, & Galovan, 2013). Moreover, a survey by American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers in Chicago (as cited in Manning, 2006) shows that 56% of divorce cases in 2002 involved internet pornography usage issue by one of the spouses. The presence of this long-term effect makes pornography distress as an issue that needs to be addressed. One thing to keep in mind is that not all women who are married to pornography users actually experience pornography distress. Bergner and Bridges (2002) acknowledged that the data that they gathered for their first study was obtained from a highly distressed population (women who deliberately complained and sought help regarding their partners’ pornography use). They then conducted a quantitative study to 100 women who were involved in romantic relationships with pornography users

(Bridges et al., 2003). In general, this group of women showed neutral to positive reactions towards their partners’ pornography use. This same kind of variation was also found to the Jabodetabek pilot study (conducted by the authors). Sixteen percent out of 33 women also supported their husbands’ pornography use, 63.16% of them had neutral attitude, while only 21.05% if them felt surprised or uncomfortable.

4 KRISTANTI & DINASTUTI

attitude towards pornography use, (5) exposure to sexual content from the media, (6) religious salience, and (7) differentiation of self. Their relations to pornography distress will be discussed below.

The inclusion of first factor (perceived frequency of pornography use) was supported by Bridges et al.’s (2003) study, which concluded that perceived frequency of husbands’ pornography use was positively correlated with pornography distress. Husbands’ frequency of pornography use-as reported by their wives-was negatively correlated with relationship quality, sexual satisfaction, and self-esteem (Stewart & Szymansky, 2012).

The second factor (duration of knowledge about pornography use) were supported by findings that women showed fluctuated responses towards their partners’ pornography use from time to time (Cavaglion & Rashty, 2010; Schneider, Weiss, & Samenow, 2012; Zitzman & Butler, 2009). W. Maltz and Maltz (2009) discussed several stages that women experiences during their discovery of partners’ pornography use. They explained that women in general would feel surprised and hurt right after the discovery of partners’ pornography use. However, over time they would be expected to show a more accepting attitude towards this situation.

Third, feelings of surprise and hurt might not be experienced universally by all women in this situation. We suspected that how women responding to their partners’ pornography use would be partially determined by how they discover the usage. There has not been found a single

literature that specifically addresses this issue, however, from case descriptions found in Ford, Durtschi, and Franklin (2012) and Ogas and Gaddam (2011) we can conclude that the reaction of distressed as feelings of being cheated or sense of worthlessness tended to be found in women who discover their partners’ pornography use by catching their partners on their acts or finding the evidence of their usage (such as internet histories or VCD/DVD materials). Meanwhile, we have not found any distress with the same level of intensity on women whose husbands honestly disclosed their pornography habit. This pattern of response would seem logical as study successfully concluded that some women felt that the heart of the problem did not lie on the usage per se, but on the dishonesty and deceit performed by their partners (Zitzman & Butler, 2009). These findings set a good foundation to include the third factor (the way of knowing about husband’s pornography use) into our hypothesis.

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS 5

negative attitudes towards pornography usage in general, it would be more likely for them to show high pornography distress when their partners were also users. Therefore, it was reasonable to suspect that women’s general attitude to pornography use also served as determinant for their pornography distress.

Fifth, it is also important to address that pornography was never a sole provider of sexual contents, as people may also find them in other forms of media, such as movies, TV series, music videos, or internet. While all kinds of information from media have strong influence to individual’s opinions and beliefs, sexual content seen from media is also potential to alter individual opinions and beliefs regarding sexual matter. Moreover, Ward and Friedman (2006) also found that the habit of viewing sexual content from television had significant and positive correlation with individual support towards recreational sexual behavior, including pornography. Therefore, women who are exposed daily to sexual content from numbers of media are expected to show less rejection towards husbands’ pornography habit. In the other words, it is less likely that those women would experience pornography distress compared to their counterparts. Therefore, it was safe to conclude that fifth factor (exposure to sexual content from the media) might contribute to women’s experience of pornography distress.

Sixth, the authors would also like to raise a religious factor as a contributor to pornography distress. Pornography is usually seen as something that goes against religious values. Several studies

showed that there was negative correlation between religiosity and individual acceptance to pornography materials (Carroll; Woodrum; Lambe; Nelson et al., as cited in Sessoms, 2011). It is probably safe as well to expect that the higher religious salience, the harder it is for her to accept if one of their significant others (e.g. spouse) is actively involved in pornography. Hypothetically, it is logical enough to expect that this acceptance difficult might result in high pornography distress.

Last, a focus to individual internal factor might also beneficial in determining the contributing factors to pornography distress. In this regard, the authors proposed differentiation of self-the degree to which one is able to balance (a) emotional and intellectual functioning and (b) intimacy and autonomy in relationships as another possible contributing factor. Highly differentiated individual is able to regulate her emotion under stressful situation. In contrast, a poorly differentiated person tends to experience more difficulties to remain calm in response to the emotionality of others and tends to be easily affected by their close ones’ behavior. The authors argue that these tendencies might serve as one possible explanation underlying pornography distressed individuals’ behavior.

The purpose of this study is to examine whether those seven factors-as a whole-contribute to pornography distress. If those seven factors together had shown significant contribution, it would be examined further which factors that show significant contribution individually.

6 KRISTANTI & DINASTUTI

primarily on the significance of pornography distress issue in marital context, while at the same time there had not been a single study intending to address this issue in Indonesia. Despite of the low number of women admitting their disapproval towards their husbands’ pornography use in the pilot study, almost half of them (42.42%) further admitted that they intend to eliminate or at least alleviate the usage. This slight inconsistency between the two data might be mediated by the nature of collectivistic culture in Indonesia which shows less favor on the expression of negative emotions (Eisenberg, Pidada, & Liew, 2001; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Oyserman, 1993). It is highly possible that women who showed support or ignorance towards their husbands’ pornography use might secretly feel the negative emotion or pornography distress. It is important to take this possibility into account as an indication that the pornography distress problem in Jabodetabek might be more serious than it looks on the raw data. This study then might become the first ever culturally sensitive reference for treating the problem and anticipating its negative consequences in marital context.

Based on the above, this research aimed to test one hypothesis and answer one question: H1: Perceived frequency of husband’s pornography use, the duration of knowledge about husband’s pornography use, the way of knowing about husband’s pornography use, attitude towards pornography use, exposure to sexual content from the media, religious salience, and differentiation of self, contributed together and significantly to pornography

distress.

R1: Which factors among the seven proposed contribute individually to pornography distress?

Methods

Participants

Participants were 161 Indonesian women who met the following criteria: (1) married; (2) were aware of their husbands’ pornography use; (3) resided in Greater Jakarta which include Jakarta, Bogor, Depok, Tangerang, or Bekasi. There was no age limitation for participation as one of most important part of this study is the variation of its subjects (participants aged from 19-57 years). Mean age of participants was 35.81 years (SD = 9.77). City of residence were check against the estimated population of married women living in Jabodetabek (estimated through the number of household within the five areas; Badan Pusat Statistik Jawa Barat, 2010; Badan Pusat Statistik Kota Depok, 2010; Badan Pusat Statistik Kota Tangerang, 2011; “Provinsi DKI”, 2010). Participants were found to be representative in terms of domicile.

Procedure

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS 7

pornography use. Complete responses were obtained from 161 eligible participants.

Measures

The instrument consisted of 120 items and was divided into seven parts. Part one consisted of a short instruction and items

related to socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, city of residence,

education, religion, ethnicity, economic status, occupation, marriage status, age of spouse, and age of marriage). To preserve confidentiality, participants were allowed to provide initials instead of their real names. To avoid misinterpretation, participants were informed about the definition of pornography use: the act of seeing, reading, or hearing pornographic materials (e.g. pictures, sketches, illustrations, photos, narrations, sounds, moving images, animations, conversations) with the purpose of obtaining sexual pleasure. Any kinds of sexual contact with real persons are not considered as pornography here. Part two, three, four, five, and six consisted items to measure our research variable:

Pornography distress: Pornography Distress Scale-Short Form (32-PDS). 32-PDS was constructed by Bridges et al. (2003) measuring the extent of negative feelings experienced by women as the response to their partners’ pornography use. This measure was adapted to Indonesian version for the purpose of this study (Cronbach’s alpha= .96).

Perceived frequency of husbands’ pornography use. This variable was measured by asking participants with the following question: “To your knowledge,

how often does your husband use pornography?” with the following options: 1) less than once a month; 2) two to four times a month; 3) one to two times a week; 4) three to five times a week; 5) once a day; 6) several times a day.

Duration of knowledge about husband’s pornography use. This variable was measured by asking participants with the following question: “How long have you known about your husband’s pornography use? (please give your best estimate)” Participants were asked to respond in year and month (___ year(s) and ___ month(s)).

The way of knowing about husband’s pornography use. This variable was measured by asking participants with the following question: “How did you first find out about your husband’s pornography use?” with the following options: 1) had been asked by husband to join his pornography use; 2) had been told by husband about his pornography use; 3) had found proof of his pornography use; 4) had caught him in his pornography using act; 5) others (please specify).

8 KRISTANTI & DINASTUTI

rate: 1) the frequency of their consumption to those media from the last 12 months (from the scale of 1 to 4; 1 = “rarely”; 2 = “sometimes”; 3 = most of the time”; 4 = “always”); 2) the intensity of sexual content involved in those media (from the scale of 1 to 4: 1 = “no sexual content”; 2 = “a little sexual content”; 3 = “some sexual content”; 4 = “a lot of sexual content”). Because the scale of 1 refers to no sexual content at all, for analytical purpose the intensity of sexual content scale of 1 to 4 would be converted to 0 to 3. For each television show, internet site, newspaper, and magazine, the frequency score would then be multiplied by the intensity score, and finally the result of those multiplications would be added to produce the final exposure to sexual content from the media score.

Attitude towards pornography use:

Attitude towards Pornography Use Scale (APUS). APUS was constructed originally for the purpose of this study, measuring individual psychological tendency to give favorable or unfavorable evaluation towards pornography use (e.g. how individual thinks, feels, or reacts to pornography use). Cronbach’s alpha on this scale was .92.

Religious salience: Religious

Salience Scale (RSS). RSS was

constructed originally for the purpose of this study, measuring the extent which religious belief influences individual’s thoughts and feelings in his daily lives. Cronbach’s alpha on this scale was .96.

Differentiation of self: Differentiation

of Self Inventory (DSI). DSI was

constructed by Skowron and Friedlander

(1998) measuring the degree to which one is able to balance (a) emotional and intellectual functioning and (b) intimacy and autonomy in relationships (Bowen, as cited in Skowron & Friedlander, 1998). This measure originally consists of four subscales (Skowron & Friedlander, 1998): Emotional Reactivity (ER; “the degree to which a person responds to environmental stimuli with emotional flooding”, I Position (IP; “reflects a clearly defined sense of self and the ability to thoughtfully adhere to his convictions when pressured to do otherwise”), Emotional Cutoff (EC; “reflects feeling threatened by intimacy and feeling excessive vulnerability in relations with others”), and Fusion with Others (FO; “reflects emotional over involvement with others, including triangulation and over identification with parents”). Based on personal correspondence with the original author, only ER, IP, and EC subscales were adapted to Indonesian version for the purpose of this study, as these three subscales translate better across culture. Cronbach’s alpha on full scale and three subscales (ER, IP, and EC) were .84, .76, .77, and .77 respectively.

Results

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS 9

was 224, it can be concluded that the Table 1

Descriptive Statistics of Continuously-Scaled Research Variables

Mean Median Score range of the instruments

Score range of the obtained data

Pornography distress 92.7343 88.0000 7-224 34-189

Duration of knowledge about husband’s pornography use

8.535 (years)

5.000

(years) -

1 (week)-40 (years)

Attitude towards

pornography use 38.8137 39.0000 6-84 12-79

Exposure to sexual content from the media

17.2422 16.0000 0-144* 0-80

Religious salience 29.4886 31.0000 7-35 13-35

Differentiation of self 127.4846 127.0000 6-204 83-180

Table 2

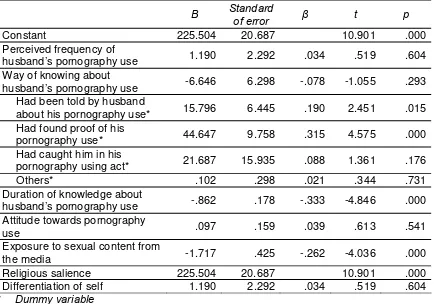

Hypothesis Testing using Multiple Regression Analysis (Enter Method)

B Standard

of error β t p

Constant 225.504 20.687 10.901 .000

Perceived frequency of

husband’s pornography use 1.190 2.292 .034 .519 .604

Way of knowing about

husband’s pornography use -6.646 6.298 -.078 -1.055 .293

Had been told by husband

about his pornography use* 15.796 6.445 .190 2.451 .015

Had found proof of his

pornography use* 44.647 9.758 .315 4.575 .000

Had caught him in his

pornography using act* 21.687 15.935 .088 1.361 .176

Others* .102 .298 .021 .344 .731

Duration of knowledge about

husband’s pornography use -.862 .178 -.333 -4.846 .000

Attitude towards pornography

use .097 .159 .039 .613 .541

Exposure to sexual content from

the media -1.717 .425 -.262 -4.036 .000

Religious salience 225.504 20.687 10.901 .000

Differentiation of self 1.190 2.292 .034 .519 .604

10 KRISTANTI & DINASTUTI

research participants tended to show low pornography distress (median = 88). The data also showed that the participants tend to acknowledge their husbands’ pornography use for quite short time (5 years). Considering the possible range of 6-84, the data also showed that participants tended to hold normal to negative attitude towards pornography use (median = 39). The median of 16 (compared to 0-144 of range) showed that participants tended to be exposed to little amount of sexual content from media. On the other hand, median of 31 (compared to 7-35 of range) and 127 (compared to 6-204 of range) also showed that research participants tended to have high religious salience and differentiation of self.

The descriptive statistics also showed that the majority of participant perceived very low frequency of husbands’ pornography use (over 44% of them reported less than once a month usage).

Another descriptive statistics showed a diverse figure on participants’ ways of knowing about their husbands’ pornography use. However, it might be concluded that the majority of participants acknowledged their husbands’ pornography use by finding proof of their husbands’ pornography use themselves (31.06%), through their husbands’ invitation to join them (29.19%), or through their husbands’ disclosure (29.19%).

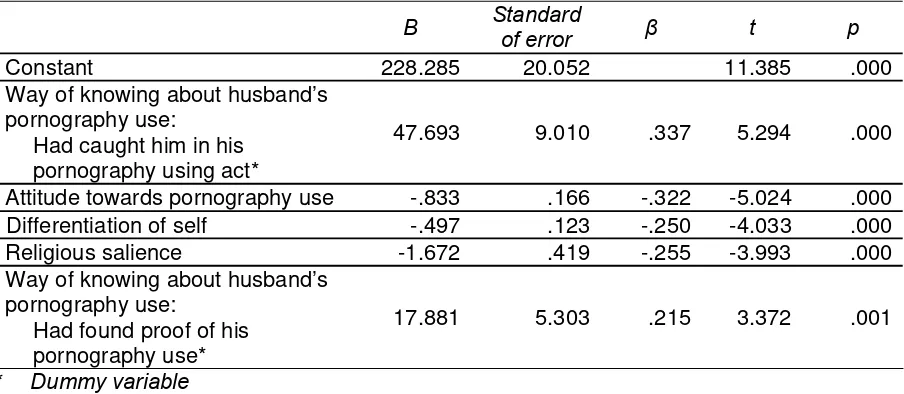

Table 3

Hypothesis Testing using Multiple Regression Analysis (Stepwise Method)

B Standard

of error β t p

Constant 228.285 20.052 11.385 .000

Way of knowing about husband’s pornography use:

Had caught him in his pornography using act*

47.693 9.010 .337 5.294 .000

Attitude towards pornography use -.833 .166 -.322 -5.024 .000

Differentiation of self -.497 .123 -.250 -4.033 .000

Religious salience -1.672 .419 -.255 -3.993 .000

Way of knowing about husband’s pornography use:

Had found proof of his pornography use*

17.881 5.303 .215 3.372 .001

* Dummy variable

Hypothesis testing

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS 11

distress.

To test this hypothesis, we made use of multiple regression analysis, using Enter method (Table 2). One variable (way of knowing about husband’s pornography use) was measured in nominal scale, and for this case we made use of dummy variables to include it on the regression analysis.

The result showed that perceived frequency of husband’s pornography use, the duration of knowledge about husband’s pornography use, the way of knowing about husband’s pornography use, attitude towards pornography use, exposure to sexual content from the media, religious salience, and differentiation of self, contributed together and significantly to pornography distress (F(10,150) = 12.200, p < 0.05). However, this analysis had not yet determined which of the seven factors individually contributed to pornography distress. This issue will be addressed on next research question.

Answering research question

Research question 1: Which factors among the seven proposed contribute individually to pornography distress?

Using the Stepwise method of multiple regression analysis (Table 3) it was found that not all of the seven proposed factors actually contributed individually to pornography distress. Only four of them were: the way of knowing about husband’s pornography use (significant only on two dummy variables: had caught him in his pornography using act and had found proof of his pornography use), attitude towards pornography use, differentiation of self, and

religious salience (F(5,155) = 23.456, p < 0.05). This regression model contributed for 41.20% of the variation among pornography distress.

The direction of each contribution may also be concluded. The biggest contributor (way of knowing about husband’s pornography use, dummy variable: 1) had caught him in his pornography using act (t = 5.294, p < .05); 2) had found the proof of his usage (t = 3.372, p < .05)) contributed in positive direction. In other words, if a woman discovered her husband’s pornography use by one of those two modes, her pornography distress would be increased. This finding confirmed the initial notion that women who find out about their husbands’ pornography use in a way that does not suggest their husbands’ openness about the issue to them, would then experience higher pornography distress.

12 KRISTANTI & DINASTUTI

An interesting result was shown by religious salience variable. The research data showed that this variable contributed to pornography distress negatively, that the higher religious salience, the lower pornography distress would be. This result was not consistent with the initial expectation. This interesting inconsistency would be further discussed in discussion.

Additional Findings

This research also addressed several other aspects that may be related to pornography distress in marital context. Some additional information was gathered regarding participants’ religion, marital age, their own pornography use (whether they themselves actively use pornography), frequency of their own pornography use, pattern of husbands’ pornography habits (whether their husbands use pornography in a solitary way, with the wives’ companion, or with their friends’ companion), and when the discovery of their husbands’ pornography use took place (was it before or after marriage).

Due to the unevenness of the distributions, analysis for these additional variables was conducted using non-parametric statistics. The results indicated that some of the variables (participants’ religion, their own pornography use, and pattern of husbands’ pornography habits) might add more information to our understanding of pornography distress. It was found that Buddhist women tended to show lower level of distress in regards of husbands’ pornography use, compared to Christian women (U = 145.5, p < .125). Also, women who themselves were actively

using pornography tended to show lower level of distress compared to women who were not involved in pornography (U = 931, p < .05). Moreover, women whose husbands’ usually used pornography with their friends experienced more pornography distress compared to women whose husbands’ had usually used the pornography with them (U = 321, p < .167).

Discussion

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS 13

achieve some sort of agreement and understanding to solve pornography distress issues.

This finding also showed that despite of the absence of similar study conducted in Indonesia, the present study was successful on giving valuable information. This study also showed an interesting result in regards to religious salience variable. This particular variable actually showed significant contribution in the opposite direction compared to the initial hypothesis. It was expected that high identification to religious values might prevent women to accept their husbands’ pornography use. In other words, the higher religious salience, the higher pornography distress.

This unconfirmed hypothesis might be explained by revisiting the role of religious salience in woman’s dynamic of emotion and distress while facing this issue. A couple of findings showed that religiosity can play a vital card in helping individual to be more resilient and adaptable while facing difficult situation (Van Dyke, Glenwick, Cecero, & Kim, 2009; Jang & Johnson, 2004; Marks, 2005; Roemer, 2010; Salsman & Carlson, 2005). Moreover, some findings showed that religiosity has become one of the main coping strategy for Indonesian individuals (Fathi, Nasae, & Thiangchanya, 2010; Ismail & Basuki, 2012; Safaria, Othman, &Wahab, 2010). Findings by Permatasari (2006) and Felicia (2005) also showed that one of the most popular coping strategies used by married women in Indonesia was turning to religion. With this notion in mind, we might see this present finding in

different light, that high religious salience may provide women to evaluate her husband pornography use more positively. Hence, she experiences lower pornography distress.

Despite delivering interesting results, this study also met some limitations. One of them was low participation rate. Large number of participants (at total of 237 people) refused to continue their participation in this study. This might be explained by several factors: 1) lengthy questionnaire and 2) the nature of talking about sexuality in Indonesia, which is still considered taboo.

The second limitation was generalization. Most of the samples were women with low pornography distress. This is an important matter to be addressed as these research findings may not be applicable to the more varied sample of women. The conception of sexual taboo in Indonesia may explain the low pornography distress showed by the majority of sample. It is very possible that women who agree to participate fully in this research are the ones who no longer hold negative attitude towards sexual discussion. Therefore, it seems logical if they also showed positive reactions towards their husbands’ pornography use.

14 KRISTANTI & DINASTUTI

possible explanations why the first variable failed to show its contribution. Firstly, most of data (44.72%) were skewed on the lowest frequency (most participants perceived their husband pornography use to be less than once a month). This homogenous data might lower statistical power of rejecting null hypothesis. Despite this methodological limitation, it is possible that this result reflected the real relationship between perceived frequency of husband’s pornography use and pornography distress, that this variable was not a contributor to pornography distress. In this case, the heart of the problem may not lie on how frequent the pornography use is, it is actually about the honesty of partners in disclosing their habits. This notion is supported by one of this research finding that the way of finding out about husband’s pornography use significantly contributed to participants’ pornography distress, especially if this revelation came from catching husbands’ act firsthand or finding proof of their husbands’ behavior. Hence, it is possible that the perceived frequency of pornography use doesn’t play a significant role in building the problem, as long as the husbands are not being secretive about their usage.

The reason why the second variable (duration of knowledge about husband’s pornography use) did not show significant contribution might also be due to the skewed data (most participants had just found out about their husbands’ pornography use) and this condition might also lower the statistical power of rejecting null hypothesis. The second possibility is related to memory bias. Asking about when

approximately did the participants find out about their husbands’ pornography use might force participants to retrieve old memories (almost half of the participants have been married for 15 years). Participants’ limitation on remembering such information might produce inaccurate data.

There might also another interesting way to interpret this particular finding. The reason why this variable was included in this research model and became subject to be hypothetically tested was the notion from W. Maltz and Maltz (2009) about stages that women experienced while discovering about their partners’ pornography use. We translated these stages to the variable of duration. The idea was: if stages were seen as a reflection of women’s acceptance from time to time, then their duration of knowing about their husbands’ pornography use would also play part on their experience of pornography distress. However, this research finding raised the need of revisiting this translation. It is possible that each woman goes through these stages differently: there might be women who quickly moved between stages, but there might also be women who need longer time to move between stages. Therefore, their duration of knowing their husbands’ pornography use does not always reflect their current and advanced stages.

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS 15

asking the participants to judge the degree of sexual content contained in their each of media consumption. This self-report method was actually supported by Bleakley et al. (2008), as the impact that a sexual media has on an individual is determined largely by how he/she perceived it rather than the actual content it has. However, there is a possibility that participants who frequently exposed to sexual contents had actually get used to the exposure and experience less awareness on what they receive. Without this awareness, the subjective report would no longer give an accurate description on what the participants actually perceived. Therefore, we suggest that future researcher may consider using judges in determining the degree of sexual content.

To end this discussion, we would like to address one more important thing that the readers should keep in mind related to the interpretation of research findings. This research was designed from women’s point of view to capture the overall trend of pornography distress in Indonesia. While the research had been successful on its part, it had only covered one side of the story. Therefore, it is strongly suggested that future researcher would address this issue from the husband or couple’s perspective and also make use of qualitative designs to get more in-depth data.

References

Badan Pusat Statistik Kota Depok (2010). Hasil sensus penduduk 2010: Data agregat per Kecamatan di Kota Depok. Depok: BPS.

Badan Pusat Statistik Kota Tangerang (2011). Kota Tangerang dalam angka 2011. Tangerang: BPS.

Badan Pusat Statistik Propinsi Jawa Barat (2010). Jawa Barat dalam angka 2010. Bandung: BPS.

Bergner, R., & Bridges, A. (2002). The significance of heavy pornography involvement for romantic partners: Research and clinical implications. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 28, 193-206.

Bishara, A. J., & Hittner, J. B. (2012). Testing the significance of a correlation with non-normal data: Comparison of Pearson, Spearman, transformation, and resampling approaches. Psychological Methods, 17, 399-417.

Blaine, B., & Crocker, J. (1995). Religiousness, race, and psychological well-being: Exploring social psychological mediators. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(10), 1031-1041.

Bleakley, A., Fishbein, M., Hennessy, M., Jordan, A., Chernin, A., & Stevens, R. (2008). Developing respondent based multi-media measures of exposure to sexual content. Common Methods of Measurement, 2(1-2), 43-64.

Bridges, A., Bergner, R., & Hesson-McInnis, M. (2003). Romantic partner’s use of pornography: Its significance for women. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 29, 1-14.

Carroll, J. L. (2010). Sexuality now: Embracing diversity (3th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth.

16 KRISTANTI & DINASTUTI

female partners of cybersex and cyber-porn dependents. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 17, 270-287.

Eisenberg, N., Pidada, S., & Liew, J. (2001). The relations of regulation and negative emotionality to Indonesian children’s social functioning. Child Development, 72(6), 1747-1763.

Fathi, A., Nasae, T., & Thiangchanya, P. (2010, April). Workplace stressors and coping strategies among public hospital nurses in Medan, Indonesia. Presented in International Conference of Humanities and Social Sciences, Songkhla, 10 April 2010.

Felicia, J. P. (2005). Stress dan coping stress perempuan korban kekerasan dalam rumah tangga yang tetap mempertahankan pernikahannya: Studi pada perempuan berpendidikan tinggi dan bekerja dan menjadi korban oleh suaminya. Unpublished undergraduate thesis. Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya, Jakarta.

Ford, J. J., Durtschi, J. A., & Franklin, D. L. (2012). Structural therapy with a couple battling pornography addiction. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 40, 336-348.

Gravetter, F. J., & Wallnau, L. B. (2013). Statistics for the behavioral sciences. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Ismail, R. I., & Basuki, B. (2012). Coping strategies related to total stress score among post gradual medical students and residents. Health Science Journal of Indonesia, 3(2), 1-5.

Jang, S. J., & Johnson, B. R. (2004). Explaining religious effects on distress

among African Americans. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 43(2), 239-260.

Kominfo Sebut Indonesia Pengakses Situs Porno Terbesar di Dunia (2012, 16 Juni). Seruu.com. Retrieved from http://utama.seruu.com/read/2012/06/1 6/103621/kominfo-sebut-indonesia- pengakses-situs-porno-terbesar-di-dunia.

Maltz, W., & Maltz, L. (2009). The porn trap: The essentials guide to overcoming problems caused by pornography. New York City, NY: William Morrow Paperbacks.

Manning, J. C. (2006). The impact of internet pornography on marriage and the family: A review of the research. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 13, 131-165.

Markey, P. M., & Markey, C. N. (2012). Online pornography seeking behaviors. In Zheng, Y. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of cyber behavior. (pp. 837-847). Hershey, PA: IGI Global Snippet.

Marks, L. (2005). Reljgion and bio-psycho-social health: A review and conceptual model. Journal of Religion and Health, 44, 173-186.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224-253. Ogas, O., & Gaddam, S. (2011). A billion

wicked thoughts: What the internet tells us about sexual relationships. New York City, NY: Penguin Group.

PORNOGRAPHY DISTRESS 17

Retrieved from http://indonesiarayanews.com/news/na

sional/03-28-2013-15-48/netty- heryawan-sesalkan-tingginya-pengakses-konten-pornografi.

Oyserman, D. (1993). The lens of personhood: Viewing the self and others in multicultural society. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(5), 993-1009.

Permatasari, P. (2006). Stress dan Coping Stresspada Perempuan Hamil Pengidap HIV. Unpublished undergraduate thesis. Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya, Jakarta. Pitoyo, A. (2012, 22 March). Akses Situs

Porno: RI Masih Duduki Peringkat 1.

Bisnis.com. Retrieved from

http://archive.bisnis.com/articles/akses- situs-porno-ri-masih-duduki-peringkat-1.

Poulsen, F. O., Busby, D. M., & Galovan, A. M. (2013). Pornography use: Who uses it and how it is associated with couple outcomes. Journal of Sex Research, 50(1), 72-83.

Provinsi DKI Jakarta Per Kab/Kota Tahun 2010. (2010). Badan Pusat Statistik Provinsi DKI Jakarta. Retrieved from http://jakarta.bps.go.id/index.php?bWV udT0yMzA0JnBhZ2U9ZGF0YSZzdWI9 MDQmaWQ9MTE=.

Ramadhan, M. (2013, 14 January). Tekan Pornografi, Pelajar di Tangerang Dibatasi Gunakan HP. Merdeka.com.

Retrieved from http://www.merdeka.com/peristiwa/teka

n-pornografi-pelajar-di-tangerang-dibatasi-gunakan-hp.html.

Roemer, M. K. (2010). Religion and

psychological distress in Japan. Social Forces, 89(2), 559-583.

Roviana, A. F. (2011). Perilaku seks bebas pranikah dan penggunaan media pornografi atau sexual explicit material (sem) pada mahasiswa Universitas

Diponegoro. Unpublished

undergraduate thesis. Universitas Diponegoro, Semarang.

Safaria, T., Othman, A. B., & Wahab, M. N.A. (2010). Religious coping, job insecurity, and job stress among Javanese academic staff: A moderated regression analysis. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 2(2), 159-169.

Salsman, J. M., & Carlson, C. R. (2005). Religious orientation, mature faith, and psychological distress: Elements of positive and negative associations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 44(2), 201-209.

Schneider, J. P., Weiss, R., & Samenow, C. (2012). Is it really cheating? Understanding the emotional reactions and clinical treatment of spouses and partners affected by cybersex infidelity. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 19, 123-139.

Sebagian Besar Pengguna Internet Buka Film Porno (2013, February 18). Poskotanews.com. Retrieved from http://m.poskotanews.com/2013/02/18/ sebagian-besar-pengguna-internet-buka-film-porno/.

18 KRISTANTI & DINASTUTI

Stewart, D. N., & Szymanski, D. M. (2012). Young adult women’s reports of their male romantic partner’s pornography use as a correlate of their self-esteem, relationship quality, and sexual satisfaction. Sex Roles, 67, 257-271. Strager, S. (2003). What men watch when

they watch pornography. Sexuality & Culture, 7, 50-61.

Suryanto (2009, November 4). Menkominfo: Indonesia Pengakses Situs Porno Terbesar di Dunia. Antara

News. Retrieved from

http://www.antaranews.com/berita/1257

335727/menkominfo-indonesia-pengakses-situs-porno-terbesar-dunia. Van Dyke, C. J., Glenwick, D. S., Cecero,

J. J., & Kim, S. K. (2009). The relationship of religious coping and spirituality to adjustment and psychological distress in urban early adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 12(4), 369-383.

Ward, L. M., & Friedman, K. (2006). Using TV as guide: Associations between television viewing and adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(1), 133-156.

Zitzman, S. T., & Butler, M. H. (2009). Wives’ experience of husbands’ pornography use and concomitant deception as an attachment threat in the adult pair-bond relationship. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 16, 210-240.

‘AKTIF’ TEACHER TRAINING 19

Jurnal Psikologi Indonesia Himpunan Psikologi Indonesia

2017, Vol. XII, No. 1, 19-30, ISSN. 0853-3098

‘AKTIF’ TEACHER TRAINING PROGRAM TO

INCREASE TEACHERS’ SELF EFFICACY IN

TEACHING CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL

NEEDS

(PROGRAM PELATIHAN GURU ‘AKTIF’

UNTUK MENINGKATKAN EFEKTIVITAS GURU

DALAM MENGAJAR ANAK BERKEBUTUHAN

KHUSUS

)

Amitya Kumara, Dian Mufitasari,

Krysna Yudy Nusantari,

and

Iga Serpianing Aroma

Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, IndonesiaThe purpose of this research is toexamine the effectiveness of AKTIF Teacher training program to increase the teachers’ self-efficacy in teaching children with special needs. Untreated Control Group Design with Dependent pre-test and post-test sample method was used. 17 teachers were selected through purposive sampling method as experiment group and 5 teachers as control group. One-Way ANOVA test showed the three methods (case discussion, roleplay, and simulation) indicatedno fundamental difference in improving self-efficacy (F = 2.852, p = .091). Data analysis using the Mann Whitney U Test showed that the case discussion method significantly increased self-efficacy (zcase discussion = -2.410, p = .016; zsimulation = -0.754, p = .451; zrole play = -1.916, p = .055). Wilcoxon-signed rank test showed that case discussion (p = 0.043) and roleplay (p = 0.035) were significant to improve self-efficacy, as opposed to simulation method which was not (p = 0.063).

Keywords: teacher training program, children with special needs, teacher’s self efficacy

Tujuan penelitian ini adalah untuk mengetahui efektivitas program pelatihan Guru AKTIF (Asih Kreatif Terampil InspiratiF) guna meningkatkan efikasi diri guru dalam mengajar anak berkebutuhan khusus. Desain penelitian menggunakan metode untreated control group with dependent pre-test and post-test. Subjek penelitian ditentukan dengan metode purposive sampling melibatkan 17 guru sebagai kelompok eksperimen dan 5 guru sebagai kelompok kontrol. Berdasarkan uji One Way ANOVA diketahui bahwa diantara ketiga metode (diskusi kasus, roleplay, dan simulasi), tidak memiliki perbedaan yang signifikan dalam meningkatkan efikasi diri (F = 2.852, p = .091). Hasil uji statistika dengan Mann Whitney U Test menunjukkan metode diskusi kasus signifikan meningkatkan efikasi diri (zdiskusi kasus = -2,410, p = 0,016; zsimulasi = -0,754, p = 0,451, zrole play = -1,916, p = 0,055). Uji Wilcoxon signed rank menunjukkan metode diskusi kasus (p = 0,043) dan role play (0,035) signifikan meningkatkan efikasi diri. Sedangkan metode simulasi tidak signifikan untuk meningkatkan efikasi diri guru (p = 0,063).

Kata kunci: pelatihan guru, anak berkebutuhan khusus, efikasi diri guru

20 KUMARA, MUFITASARI, NUSANTARI, & AROMA

Survey results from a research about Children with Special Needs in Gunungkidul DIY performed by Kumara (2015) showed that during the four years of implementation of inclusive education (2011-2015), continuous training for teachers was still underdeveloped. Only 1 to 2 persons from each school were ever trained about the basic of inclusive education and how to attend to children with special needs. Teachers with seminars and workshops experiences still encountered problems in understanding the training materials, and therefore impeding the implementation of said system. Teachers were not confident enough of their ability, for the training was not continual and was limited. In addition to that, seminars and workshops they ever attended only covered the pedagogical side of their job, but overlooked the psychological one. This speaks about how the seminars and workshops were lacking both in quantity and quality.

The lack of knowledge and skills of the staff and its inclusion makes teachers feel less able to teach children with special needs. Teachers are considered to have low self-efficacy. Regular school teachers feel they have difficulty in meeting the needs of students with special circumstances although they have been supported with a special education program. Gallis and Tanner (1995) stated that regular teachers usually have low confidence in their ability to implement inclusive education system in regular classrooms. Research conducted by Hofman and Kilimo (2014) later also

discovered that teachers faced many problems in implementing inclusive education, especially in dealing with students of various disabilities, shortage of teaching and learning materials, inadequate training, and unfavorable working environment. Teachers with low self-efficacy tend to face more problems in implementing inclusive education compared to teachers with high self-efficacy. Clearly, self-efficacy is a variable that is consistently correlated with positive teaching and student learning outcomes (Penrose, Perry, & Ball, 2007).

‘AKTIF’ TEACHER TRAINING 21

students, how they conduct classroom management, and get everyone in the classroom involved. It also affects student achievement in the classroom.Teachers with high self-efficacy can affect into increased motivation, esteem, self-direction, and positive attitudes toward school.

According to Hofman and Kilimo (2014), teachers with high level of self-efficacy are as follows: (a) Able to use teaching methods adequately to promote independence of students with special needs; (b) Equipped with adequate classroom management skills and are able to handle problems in class; (c) Innovative; and (d) Able to get all students engaged in classroom activities.

A study done by Bandura (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001) revealed three aspects of teachers’ self-efficacy:

a. Student engagement

It refers to how confident teachers feel in establishing relationship with students, including motivating and resolving students’ issues. Some of the indicators shown are signs of friendliness towards students, helping them overcome problems, and knowing the way to face difficult students. b. Instructional strategies.

This refers to how teachers believe in their ability to help students score academic achievement. The indicators are: (1)the presence of confidence in addressing questions from the students, (2)possessing a comprehensive approach in explaining study materials, and (3) being well-informed about students’ level of understanding.

c. Classroom management.

It refers to teachers’ competency in managing the class in a purposeful and orderly way. The indicators are: (1) teachers are able to handle problems that arise in the classroom and ensure the teaching plan is implemented well.

This study developed a teacher training program called AKTIF, an acronym for

22 KUMARA, MUFITASARI, NUSANTARI, & AROMA

(c) teachers need more varied instructional strategies to teach elementary school children with special needs compared to ones in the secondary education level (Cipkin & Rizza, 2000).

The basic theory used in producing Teacher Effectiveness Training module by Thomas Gordon (1986) is one belonging to Carl Rogers. Carl Roger’s theory of learning is one among other humanistic learning theories that emphasizes mutual respect and no prejudice in helping people to tackle life problems. Rogers (Schunk, 2012) also said that a teacher needs to pay attention to the class atmosphere by way of emotional approach to the students. A teacher must be responsive to the needs of students, in terms of both learning materials and the emotional needs. Teachers should also create a comfortable learning environment so that students feel comfortable in class. According to Rogers, a teacher should also have a congruent attitude, unconditional acceptance, and empathy.

The AKTIF teacher training programused experiential learning approach. According to Beard & Wilson (2006), experiential learning is a process in which it involves active engagement between one and outside environment. Experiential learning was conceptualized by Kolb (1984) and contains five cycles of learning: experiencing, publishing, processing, generalizing, and applying. The AKTIF program is divided into three delivery methods, there are role play method, case discussion method, and simulation methods. Guru AKTIF program will be given at 4 inclusive primary schools

that have been designated as samples on the coast. Through the case method, the teacher will be honed to get an overview of the case and the solution (Gibson, 1998); Bridging the gap between theory and practice and develop the skills of reflection and analysis (Darling-Hammond, 2006); and explore and apply new ideas and solutions under the supervision of professionals (Lengyel & Vernon-Dotson, 2010). Kauffman (2005) also confirmed that the case method allows learners to understand the material more vividly by assessing the real situation rather than just by reading textbooks.

Roleplay methods help teachers to produce a different perspective about things to develop empathy (Fry, Ketteridge, & Marshall, 1999). Learners will acquire direct experience, participate actively and associate experiences so that it can be categorized as a constructive way of learning (Joyner & Young, 2006). As such, an active and constructive learning process will be more memorable than apassive one. By doing role plays, learners can create a new attitude in accordance with the interpretation of the experience that they feel (Sotto, 2007). Role play also proves useful to prepare teachers in addressing learning problems in class (Crow & Nelson, 2014).

non-‘AKTIF’ TEACHER TRAINING 23

threatening, (2) it allows for complex social processes to be experienced and understood throughout the learning process, (3) it is completely dependent upon individual’slearning ability, (4) it involves universal participation, (5) the learning takes place at the level of consciousness.

Case discussions, role play and simulations are all part of the experiential learning method that allows individuals to be actively involved in the learning process (Kolb, 1984). In the study, individuals receive information or experience (experiencing) on inclusive education and children with special needs through case discussions, role play, and then share their simulated experiences. Individuals then publish what they have been given to other participants. Individual review the experience (processing) and then make an abstract of the experience and draw conclusions (generalizing) regarding inclusive education and teaching children with special needs. Individuals become more knowledgeable and confidence (self-efficacy). The last cycle involves individuals to apply this knowledge to the real world (applying). The self-efficacy of each teacher increased while teaching students with special needs.

The objective of this umbrella research istoexamine the effectivenessof

AKTIFteacher training programto improve teachers’ self-efficacy in teaching children with special needs. The research held in inclusive primary schools in the coastal areas of Gunungkidul. The major hypothesis proposed by this research is that the AKTIF program significantly

increases teachers’ self-efficacy in teaching children with special needs. While the minor hypotheses proposed by this research are: (1) Role-play method works significantly to improve the teachers’ self efficacy in teaching children with special needs; (2) Case-based method works significantly to improve the teachers’ efficacy in teaching children with special needs; and (3) Simulation method works significantly increases the efficacy of teachers in teaching children with special needs.

Methods

Participants and Design

The independent variable in the study is AKTIF teacher training program, while teachers’ self-efficacy in teaching children with special needs serves as the dependent variable. The study consists of three stages: research preparation, preparation of modules and implementation of pilot research module.

Experimental method Untreated Control Group Design with Dependent Pre-Test and Post-Pre-Test Samples design was applied as shown in the Diagram 1.

24 KUMARA, MUFITASARI, NUSANTARI, & AROMA

for research subjects include some of the following: (1) Regular teachers from inclusive elementary schools around Purwosari and Panggang Gunungkidul, and (2) Homeroom teachers or subject teachers in the elementary schools

The program was held for two consecutive days and delivered by trainers with the following qualifications: (1) Psychologist, (2) Experienced in inclusive education and issues alike, and (3) Have good communication skills in Indonesian& Javanese language.

Measurement and Procedure

Research instruments: First, Basic knowledge inventory for teachers. It refers to an inventory used to measure the extent of the accuracy of teachers in responding to information obtained during the training about inclusive education and children with special needs. This test was a modification of the knowledge test prepared byHaifani (2011), consistingof 18 itemswith item discrimination index rangingfrom0.407 to 0.848 and item difficulty index rangingfrom 0.320 to 0.973.

Second, Teachers’ Self-Efficacy inventory. The said scale used in this study derived from Krisnindita (2013). The self-efficacy scale was adapted from Teacher’s Sense of Efficacy Scale that originally belonged to Tschannen-Moran & Hoy (2001) based on Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy. Teachers’ self-efficacy in dealing with students include three aspects, namely student engagement, instructional strategies, and classroom management. The scale consists of 32 statements with 19 favorable itemsand 13 unfavorable items.

Favorable items were weighed 0-3, as were the unfavorable ones. The scale of teacher efficacy obtained alpha reliability coefficient of 0.893.

This umbrella research consists of three studies with three different methods program that are AKTIF Teacher Training with case discussion method, role play, and simulation. Each research data from all three studies will be analyzed using Mann Whitney and Wilcoxong Signed Rank analysis. After which, the data analysis of this research umbrella will be analyzed quantitatively using analysis of variance F Test. F-test analysis is used to compare scores obtained by the three research groups, which are groups who received training using case discussion method, role play, and simulation. Then, based on the statistical analysis result, we can acquire the most proven effective method in increasing teachers’ self efficacy when teaching students with special needs.

Results

‘AKTIF’ TEACHER TRAINING 25

four out of nine people stayed throughout

Diagram 1. Research Design

Notes:

NR : Non Random Assignment;

O1 : Teachers’ self-efficacy before training X : AKTIF training

O2 : Teachers’ self-efficacy after training

PRE TEST

Graphic 1. Changes of Self-Efficacy Score in Case Discussion Group

Pre‐Test

Post‐Test

Graphic 2. Changes of Self-Efficacy Score in Role Play Group

pretes

postes

26 KUMARA, MUFITASARI, NUSANTARI, & AROMA

the two days training. There was no absenteeism found in the role play group.

Through normality test, it was safe to say that all data gathered from three groups had a normal distribution (zcasediscussion = -0.468; p = 0.981, zrole play = 0.579; p = 0.890, and zsimulation = 0.614; p = 0.846). Advanced data analysis was brought out by F-test to find outthe differences between the three experimental groups. Based One Way ANOVA test, the three methods did not share any significant differences in improving self-efficacy (F = 2.852, p = 0.091 by 0.091 > 0.05 ).

The Mann Whitney U test compared the score of pre-test and post-test, later revealing a higher increase in self-efficacy in the case discussion experimental group compared to the control group (z = -2.410,

p = 0.016), while participants that were trained with simulation method did not exhibit any escalation in self-efficacy between the experimental group and the control group (z = -0.754, p = 0,451 with 0.451 > 0.05). Likewise, participants who received training with roleplay method also shared similar outcome (z = -1.916, p = 0.055, with 0.055 > 0.05). This evidence confirms the minor hypothesis which states that case discussion method significantly increases teachers’ self-efficacy in teaching children with special needs. Two other hypotheses were adverse and therefore to be denied.

Further tests with Wilcoxon Signed Rank were conducted to examine the differences in the level of self-efficacy of teachers before and after training in each group. The simulation method was reported to be less significant in improving

self-efficacy compared to case discussion and roleplay method. The value of case discussion method added up to z = -2.023,

p = 0.043 (0.043 < 0.05), role play method was of z = -2.103 and p = 0.035 (0.035 < 0.05). On the other hand, the simulation method obtained a value of only z = -1.857 and p = 0.063 (0.063 > 0.05).

Significant changes of self-efficacy score took place within the experimental group with case discussion method. All participants showed a maximum increase of self-efficacy score (100%) as shown by the Graphic 1, both before and after training.

The Graphic 2 comparison of the pretest and posttest scores of trainee with role play method showed a significant change. The number of participants whoactively displayedan increase in self-efficacy was five out of eight (62.5%). The mean obtained on the pretest was 94, while that of the posttest was 103.

Self efficacy score of participants using the simulation method showed insignificant difference (Graphic 3). All participants experienced a decrease in self efficacy score before and after training. Based on observation, decrease in the score was caused by uncondusive environment during post-test. Subjects seemed to conduct the self efficacy scale hastily because participants of other groups have finished training. A condusive training delivery affects the training result.

‘AKTIF’ TEACHER TRAINING 27

suspected as the cause, such as unconducive atmosphere that occurred during the post-test and the likes.

This study highlights the importance of conducting research on self-efficacy of inclusive primary school teachers, especially in the coastal areas of Gunungkidul. The results showed there was no significant difference between the three methods in terms of increasing self-efficacy (F = 2.852, p = 0.091 (0.091 > 0.05). One among other possible reasons behind this was because the training materials that were delivered to the participants in all three groups were the same. The difference lied only in the delivery methods. Further analysis using the Wilcoxon Signed Rank indicated that case discussion method could significantly increase self-efficacy in the experimental group (z = -2.023, p = 0.043 (0.043 < 0.05). The level of self-efficacy on the subjects that belonged to the case discussion group increased after training in comparison with subjects in the control group (z = -2.410, p

= 0.016 (0.016 < 0.05). Role play method was known to increase self-efficacy in the experimental group (z = -2.103, p = 0.035 (0.035 <0.05), but the increase in efficacy itself was quite insignificant compared to the control group (z = -1.916, p = 0.055, with 0.055 > 0.05). Simulation method was found to be effective in improving self-efficacy in the experimental group (z = -1.857 and p = 0.063 (0.063 > 0.05), and there was no increase in self-efficacy when compared with the control group (z = -0.754, p = 0.451, 0.451 > 0.05). Based on these results, we can conclude that case discussion is the most effective method to

increase self-efficacy.

Discussion

The finding about the effectiveness of case discussion method was in line with that of Lengyel and Vernon-Dotson (2010), which revealed that the use of methods based on case provided an opportunity for learners to engage in discussion and receivefeedback, further developing their collaborative skills as professional teachers. Individuals were also trained to understand the concept of a case through understanding the alternatives and a variety of assumptions. Moreover, case discussion method also helps the development of the disposition of teachers to understand inclusive education better and improve their knowledge about theneeds of students with disability. The increased knowledge of teachers regarding students with special needs will simultaneously affect their confidence in teaching. Pendergast, Garvis, and Keogh (2011), also highlighted some key points in the development of teachers’ self-efficacy which were mastery experience, vicarious experience, verbal feedback and emotional support. Through case discussions, teachers were allowed some space to gain experience that would help them successfully interact with children with special needs and at the same time boost their confidence.