COMPETITION POLICY INTERFACE

WITHIN ASEAN ECONOMIC COMMUNITY FRAMEWORK

MURTI LESTARI

Business Faculty Duta Wacana Christian University

dr. Wahidin street 5-19 Yogyakarta

INDONESIA

[email protected]

ANGELINA IKA RAHUTAMI

Economic Faculty Soegijapranata Catholic University

Pawiyatan Luhur street IV/1 Semarang

INDONESIA

[email protected]; [email protected]

Abstract

ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) has many consequences not only for business but also for government. One of big issues in AEC is competition policy. The fair competition among businesses in ASEAN will succeed when there is cooperation. Up till now, legislation and jurisdiction of competition policy among ASEAN economies are not equal. Some of ASEAN economies have not had law that strictly regulates competition. They only have regulations that are associated with other laws, which regulate business by sectors.

This research describes interface of competition policy among five ASEAN economies and analyzes strength, weakness, opportunity and threat of ASEAN Competition Policy and Law (ACPL) implementation within the AEC framework.

The result of this study shows that even though there is ACPL, but there is no single authority in ASEAN that is responsible to ACPL implementation. Nowadays, ACPL only regulate the main points of business strategy that should not be infringed. There is no authority to judge for infringements. Implementation of AEC in 2015 needs single arrangement and authority. Other result also confirms that ACPL merely accommodate applicable competition regulation in each ASEAN economies but not in ASEAN level. This condition results nonstandard arrangement and no guarantee of fair competition among businesses in ASEAN.

Keywords: AEC, competition policy, ACPL, SWOT.

INTRODUCTION

1. Background

These kinds of classification become considerably important since it was realized that business players in market will choose and respond with different strategies when they face different market structures. Characteristics and strategies of perfectly competitive markets are price-taking behavior with quantity strategy, while for imperfectly competitive market is quantity-pricing strategy. Later on, these differences will give impact on market performance and welfare society. The basic theory of industrial organization also explains that perfectly competitive markets will encourage business strategies that result maximum market performance and economic welfare. On the contrary, imperfectly competitive markets will result less optimum market performance or generate welfare loss (Tirole, 1997; Martin, 2005)

The basic theory above mentioned a strong reason why countries should implement the anti-monopoly or antitrust policy. However, applications of anti-monopoly laws in the United States historically were based on situations where major cartels caused social and political chaos in the late 19th century. Because of this phenomenon, United States afterward implemented an antitrust policy which is better known as the Sherman Act. Furthermore, the application of this act was followed by many countries, especially high development countries that have several large companies.

Reflecting the historical experience and theory, many countries perceive the needs to apply antitrust policy in the context of regional and global economic cooperation. Economic cooperation in the forms of FTA (free trade area), EC (economic community), and EU (economic union) mostly arrange antitrust policy schemes in their economic cooperation agreements. There are several reasons why antitrust policy plays important role in international cooperation aspects. Partly because of the existences of business competition and antitrust regulation are aimed to avoid the unfair business practices. Another reason is according to the observation of Wooton and Zanardi (2002), which stated that Anti-Dumping Agreement aims to optimize the trade economic cooperation, will be optimal only if it is accompanied by cooperative antitrust policy.

Another more interesting reason indicated by Hoekman (2002). Research conducted by Hoekman explored that the regional integration experience demonstrates international agreements on antitrust is feasible, even between countries with initially quite different domestic antitrust policies (or no such policies at all). Most PTAs (preferential trade agreement) which have implemented the deletion of trade barriers ahead of the WTO agreement, such as the European Community, in fact also reinforced cooperation in antitrust policy. The research also concluded that economic cooperation accompanied by the integration of optimal antitrust policy improved its economic performance compared with cooperation that was not supplemented by the integration of competition policy or non-binding competition policy agreement.

ASEAN, as a regional economic cooperation in Southeast Asia, has agreed to establish the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015. ASEAN Member States (AMSs) have committed in the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Blueprint, to endeavor and introduce a national competition policy and law (CPL) by 2015. This is to ensure the levels of playing field and to foster the culture of fair business competition for enhancing regional economic performance in the long run. However, ASEAN does not seem to establish judiciary (judicial institution) in ASEAN level to complement the implementation of ASEAN competition policy and law (ACPL). Competition law and the judicial system are more submitted to each country member and regulative coordination will be carried by harmonization of law. This paper will analyze ACPL framework, and the consequences of such framework for optimizing the benefits of competition policy as well as benefit from the AEC.

(ACFC). Right now ASEAN has improved the arrangement and some countries that did not previously have competition laws, now apply the law. So it is needed to re-analyze based on current conditions.

2. Objectives

a. To examine regional cooperation and antitrust policy framework as a component of ASEAN Economic Community (AEC).

b. To identify strengths and weaknesses of ASEAN competition policy and law (ACPL) in order to optimize benefits of antitrust policy and benefits of the AEC.

3. Methodology

The qualitative method is used in the study. This study analyzes and compares the competition regulation of five countries in ASEAN regions (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Philippines). The five ASEAN countries were chosen because they have and develop more progressive competition regulation compared to Cambodia, Lao, Myanmar, Brunei and Vietnam.

To analyze the strengths and weaknesses of ACPL in order to optimize the benefits of antitrust policy and the benefits of the AEC, we will use SWOT analysis. The SWOT analysis covers:

a. Strength, analyzing strengths and advantages of ACPL in terms of AEC.

b. Weaknesses, analyzing weaknesses and shortcomings of ACPL in terms of AEC. c. Opportunity, analyzing opportunities to develop ACPL to optimize the benefits of AEC. d. Threat, analyzing the challenges of ACPL to optimize AEC.

THEORY FRAMEWORK AND LITERATURE REVIEW

1. Competition Policy Theory

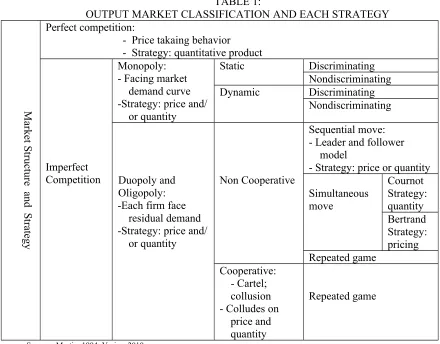

As mentioned in the previous section, the importance of regulation of competition among market participants is basically due to the different strategies when employers face different competition structures. Different strategies will further result in the performance of different markets. This also means that there is a relationship between market structure, employers’ strategy, and market performance. Detailed classification of the output market and strategy of each market forms is shown in Table 1.

The earliest theory explaining the relationship between market structure, firm strategy or conduct, and market performance was developed by Edward S. Mason in 1939. It was known as structure-conduct-performance theory or SCP theory (Martin, 2005). Mason, in his SCP theory outlined that perfectly competitive market will encourage employers to undertake strategies that generate efficiencies and further produce maximum market performance and welfare society. Instead the imperfectly competitive markets will encourage employers to take less efficient strategy and generate welfare loss.

Mason theory is also well known as the Harvard School’s theory. According to this theory, the Harvard group stated if market structure is an imperfect competition, then the government should intervene in the industry to transform the structure into a competition through anti-monopoly laws. The arguments were based on the theory that imperfect market competition will result in welfare loss. Harvard concluded that the theory was based on the assumption that market structure is static and exogenous.

and it occurs as a result of good performance. On the basis of this assumption, the Chicago group stated that the obtained monopoly is generated from the hard work, so that consumers will be loyal to their products. Therefore, the government should not intervene to affect the structure. The most important mission for the government is to ensure that various strategies in the market will not lead to a barrier to entry. Schumpeter's view that technology and entrepreneurship will develop more in a large business group with monopoly market structure than small business in perfect competition market structure. (Krouse, 1990). However, a sharp debate arose over this opinion. Tirole (1994) stated one of the arguments why a lot of people assumed that the monopoly could lead to welfare loss. Main argument pointed here was that large firms (monopoly) can generally generate diseconomies which are not necessary firm allocations or often called as X-inefficiency in order to maintain profits and position. Technical forms of X-inefficiency include behaviors of rent seeking, political scandal, and others.

As its developments from those arguments, antitrust policy does not merely regulate the market structure, but it is more focused to the strategy of the company. For example, from Table 1, in the case of duopoly market structure that follows Bertrand duopoly, there is no need to regulate it by antitrust policy. This is because Bertrand model of duopoly tends to take a "price war" that will eventually generate equilibrium which equals the perfect competition equilibrium.

Antitrust policy is a policy that is widely applied in the agreement of REC (Regional Economic Cooperation). It seems that, in addition to create fair business competition among country members, there are specific benefits of antitrust policy in supporting REC. One of the benefits is that the control is fairly good towards anti-dumping (AD) agreement when REC embodies antitrust policy in it.

Studies conducted by Wotoon and Zanardi (2002) about the relationship between trade liberalization and competition policy argued that AD is not the best approach in dealing with corporate abuse of market power. Consequently, we have sought out alternatives to AD, particularly in the context of nations increasingly being members of some form of regional trade agreement (RTA). It seems that, at least on political grounds, AD cannot be abandoned in absence of an alternative policy, despite a compelling case for its elimination (except in the case of predation). The compromise is to find some forms of alternative policy to replace AD. What might be considered as the "best" policy on efficiency grounds is a supranational application of competition policies. However, it is not considered politically feasible. Thus, whatever policy is found, it will be the "second best" from economic point of view.

2. Competition Policy Cooperation: EU, APEC, NAFTA

Even though many countries are aware about competition policy, not all of economic cooperation achieve and realize the business competition regulation. Only the small portions of more than two hundred Regional Trade Arrangements (RTAs) initiate the competition regulation for the economic cooperation. The first competition regulation on regional arrangement occurred in 1957 by European Treaty Pact, and now become a part of European Community. European community also complements its regulation with competition committee in Europe.

OECD (2000) stated that there are four options of competition regulation that can be chosen by RTAs. The five options are:

a. Voluntary convergence

b. Bilateral cooperation between competition authorities;

c. Regional agreements containing competition policy provisions; d. Multilateral competition policy agreements.

Based on competition regulation best practices, there are three forms that is interesting to be observed. They are European Union (EU), North America Free Trade Area (NAFTA) and Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). Competition regulation in EU is centralized, NAFTA which is decentralized, and APEC is not binding (Adiningsih and Lestari, 2007).

EU is the earliest and most important RTA that regulates business competition in its cooperation agreement and promotes competition policy intensively. Nowadays, EU is the most comprehensive RTAs that implements competition policy cooperation. One of the important aspects is establishment of regional supranational authority i.e. Directorate General (DG) IV. DG IV tasks are to develop additional principles, detailed rules of cooperation and disseminate information between regional and national competition authorities.

On this basis, the EU constructs measurement standard of competition law for member countries. In addition, EU also set up a centralized judicial institution i.e. European Court of Justice (ECJ). The ECJ is the European level court that would prosecute violations of antitrust policy of the member countries. DG IV and ECJ reflect the centralized competition policy. DG IV and ECJ also have the power to conduct enforcement against companies that violate. They also do not depend on the decision of the domestic government of the company.

Nowadays, business competition items that are regulated in agreement are (www.ec.europa.eu/competition):

a. Cartels, control of collusion and other anti-competitive practices

c. Mergers, control of proposed mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures involving companies that have a certain defined amount of turnover in the EU

d. State aid, control of direct and indirect aid that is given by Member States of the European Union to companies.

European Commission is the independent institution of competition policy (www.ec.europa.eu/ competition). The Commission is empowered by the Treaty to apply prohibition rules and enjoy a number of investigative powers to that end (e.g. inspection in business and non business premises, written requests for information, etc). It may also impose fines on undertakings that violate EU antitrust rules. Since 1 May 2004, all national competition authorities are also empowered to apply fully the provisions of the Treaty in order to ensure that competition is not distorted or restricted. National courts may also apply these prohibitions so as to protect the individual rights conferred to citizens by the Treaty.

Currently, antitrust regulation in EU is not adequate. Desai (2010) evaluated that one of economic crisis triggers in 2008 was regulatory failure in antirust policy implementation. Although debatable, some arguments indicate that there is needed for antitrust regulation in global level.

The Working Group on the Interaction between Trade and Competition Policy (WGTCP) has been guided by mandates at various Ministerial Conferences and in the WTO General Council. In the “July 2004 package” adopted 1 August 2004, the WTO General Council decided that the issue of competition policy “will not form part of the Work Program set out in that Declaration and therefore no work towards negotiations on any of these issues will take place within the WTO during the Doha Round”. The Working Group is currently inactive (www.wto.org). In this regard, OECD (2000) noted that it “did not retain options that have been discarded in joint discussions as unrealistic, such as full harmonization of competition laws, or an international antitrust authority with supranational powers.”

The NAFTA competition regulation cooperation agreement is decentralized. The antitrust harmonization of the NAFTA is very unique. Only USA and Canada had antitrust law (Clayton Act and Sherman Antitrust Act – USA, and Competition Act – Canada), when NAFTA was agreed. USA and Canada agreed to lead Mexico to develop antitrust policy. Because of NAFTA decentralization model, there is no regulation to be applied equally to all countries, no agency commission, and no court which can deal with competition issues conflict among member countries. Treatment standardization among member countries is needed to achieve the harmonization of competition policy. Canada Competition Bureau, the U.S Federal Antitrust and Federal Economic Competition Law (FECL) are institutions that deal with violations of fair competition among member countries. These three institutions are responsible for making convergence of competition arrangement.

In the other case, APEC regulates business competition similar with WTO. Many APEC member economies have not regulated business competition or enforced antitrust law yet. APEC established the Competition Policy and Law Group (CPLG). The CPLG, formerly known as Competition Policy and Deregulation Group, was established in 1996, when the Osaka Action Agenda (OAA) work programs on competition policy and deregulation were combined. In 1999 APEC Ministers endorsed the APEC Principles to Enhance Competition and Regulatory Reform and approved a "road map" which established the basis for subsequent work on strengthening markets in the region. To execute the Osaka Action Plan, APEC economies develop Collective Action Plan (CAP) and Individual Action Plan (IAP) in business competition regulation. APEC CPLG therefore works to promote an understanding of regional competition laws and policies, to examine the impact on trade and investment flows, and to identify areas for technical cooperation and capacity building among member economies.

THE FRAMEWORK OF ASEAN COMPETITION POLICY

COOPERATION

Nowadays, ASEAN (Association of South East Asia Nation) establishes the new integration process after the AFTA trading agreement is not sufficient enough to face up the globalization, make market and produce a better welfare. ASEAN economies are going to initiate the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in 2015 for a better and extensive economic integration.

The AEC will be a gear to realize the ASEAN regional economic. The ASEAN Leaders had originally intended to create the AEC by 2020, but in early 2007 they advanced the deadline to 2015 (AEC Blueprint, www.aseansec.org). The AEC is the realization of the end goal of economic integration as promoted in the Vision 2020, which is based on a convergence of interests of AMSs to deepen and broaden regional economic integration. The AEC scope is broader than the AFTA arrangement because it covers goods, services, investment and production factors liberalization.

The AEC blueprint (www.aseansec.org) – consistent with the goals set out in the 2007 -targets four objectives that are (i) establishing ASEAN as a single market and production base; (ii) making more dynamic and competitive with new mechanisms; (iii) inducing the equitable economic development across countries; and (iv) accelerating regional integration in the priority sectors.

ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) blueprint stated that national competition policy and law (CPL) will be introduced by 2015. The CPL will ensure a level of playing field and foster a culture of fair business competition for enhanced regional economic performance in the long run (www.asean.org). ASEAN has launched the Regional Guidelines and Handbook in CPL for advocacy and outreach purposes. The ASEAN Regional Guidelines on Competition Policy (Regional Guidelines) were completed by the ASEAN Experts Group on Competition (AEGC). The guidelines focus on three key areas of competency, i.e., (i) institutional building; (ii) enforcement, and (iii) Advocacy.

1. Definition of competition policy (ASEAN secretariat, 2010)

Competition policy can be broadly defined as a governmental policy that promotes or maintains the level of competition in markets, and includes governmental measures that directly affect the behaviour of enterprises and the structure of industry and markets. Competition policy basically covers two elements:

a. a set of policies that promote competition in local and national markets, such as introducing an enhanced trade policy, eliminating restrictive trade practices, favouring market entry and exit, reducing unnecessary governmental interventions and putting greater reliance on market forces.

b. competition law, comprises legislation, judicial decisions and regulations specifically aimed at preventing competitive business practices, abuse of market power and anti-competitive mergers. It focuses on the control of restrictive trade (business) practices (such as competitive agreements and abuse of a dominant position) and anti-competitive mergers and may also include provisions on unfair trade practices.

The objectives of competition policy can be achieved through the setting up of one or more competition regulatory bodies.

2. Scope of CPL (ASEAN secretariat, 2010)

AMS’s territory, unless exempted by law. The coverage of national competition policy may include:

a. Prohibition of Anti-competitive Agreements (horizontal and vertical). Horizontal agreement means an agreement entered between two or more enterprises operating at the same level in the market. On the other side, vertical agreement means an agreement entered between two or more enterprises, each of which operates, for the purposes of the agreement, at a different level of the production or distribution chain, and relating to the conditions under which the parties may purchase, sell or resell certain goods or services. ASEAN Member States (AMSs) should consider prohibiting horizontal and vertical agreements between undertakings that prevent, distort or restrict competition in the AMSs’ territory, unless otherwise exempted. AMSs may consider identifying specific “hardcore restrictions” (e.g., price fixing, bid-rigging, market sharing, limiting or controlling production or investment), which need to be treated as per se illegal.

b. Prohibition of Abuse of dominant position (market power). Dominant position refers to a situation of market power, where an undertaking, either individually or together with other undertakings, is in a position to unilaterally affect the competition parameters in the relevant market for a goods and services. Abuse of a dominant position occurs where the dominant enterprise exploits its dominant position in the relevant market or excludes competitors and harms the competition process.

c. Prohibition of anti-competitive mergers. Mergers constitute, in principle, legitimate commercial transactions between economic operators. AMSs may consider prohibiting mergers that lead to substantial lessening of competition or would significantly impede effective competition in the relevant market or in a substantial part of it.

d. The prohibition of other restrictive trade practices.

3. Role and responsibilities of competition regulatory body

AMSs may want to give the competition regulatory body the mandate to: a. Implement and enforce national competition policy and lawb. Interpret and elaborate on competition policy and law c. Advocate competition policy and law

d. Provide advice on competition policy and law to the legislator and the government

e. Act internationally as the national body representative of the country in international competition matters.

The competition regulatory body may undertake responsibilities such as:

a. Establishing and issuing regulation and other implementing and /or interpretative measures

b. Developing and disseminating plain language guidelines and publications to businesses and consumers on competition policy and law provisions

c. Developing and publishing comprehensive guidelines

d. Carrying out competition advocacy and education activities or undertaking market competition studies and publishing regular reports

e. Carrying out investigations of prohibited anti-competitive activities on its own initiative f. Carrying out investigation of suspected competition law violations across a whole sector

of the economy

g. Enforcing competition law

h. Interpreting the competition law provisions

i. Establishing processes to receive and assess notifications for exemptions from competition policy and law

k. Providing advice and opinions

l. Promoting exchange of non-confidential information m. Promoting capacity building

OVERVIEW OF THE REGULATORY SYSTEM OF COMPETITION

POLICY IN ASEAN COUNTRIES

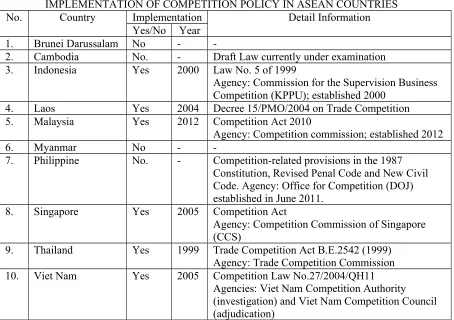

ASEAN member countries have declared about the implementation of AEC 2015 since 2007. In the aspect of competition policy, ASEAN does not form a single arrangement of regulatory system as well as the European Community. Similarly, in terms of agency and court, ASEAN delivers independent responsibility to each member of it.

TABLE 2:

IMPLEMENTATION OF COMPETITION POLICY IN ASEAN COUNTRIES No. Country Implementation Detail Information

Yes/No Year 1. Brunei Darussalam No -

-2. Cambodia No. - Draft Law currently under examination 3. Indonesia Yes 2000 Law No. 5 of 1999

Agency: Commission for the Supervision Business Competition (KPPU); established 2000

4. Laos Yes 2004 Decree 15/PMO/2004 on Trade Competition 5. Malaysia Yes 2012 Competition Act 2010

Agency: Competition commission; established 2012

6. Myanmar No -

-7. Philippine No. - Competition-related provisions in the 1987 Constitution, Revised Penal Code and New Civil Code. Agency: Office for Competition (DOJ) established in June 2011.

8. Singapore Yes 2005 Competition Act

Agency: Competition Commission of Singapore (CCS)

9. Thailand Yes 1999 Trade Competition Act B.E.2542 (1999) Agency: Trade Competition Commission 10. Viet Nam Yes 2005 Competition Law No.27/2004/QH11

Agencies: Viet Nam Competition Authority (investigation) and Viet Nam Competition Council (adjudication)

Source: ASEAN Handbook on Competition, 2013

The AEC agreement will be phased in gradually. In accordance with the agreement signed in 2007, AEC 2015 will be initially implemented for five ASEAN countries; namely Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippine, Singapore, and Thailand. However, from Table 2, among the ASEAN-5, not all of those have Competition Acts. Moreover, among countries that already had implemented one(s), the regulation standards are varied. The following sections will describe regulatory system of competition policy in the ASEAN-5.

1. Indonesia

Indonesia has had business competition law since 1999 (and has implemented since 2000), namely The Act number 5 (www.kppu.go.id). This Act No. 5 is concerning prohibition of monopoly practices and unfair business competition. The principle of the Act No. 5/1999 is economic democracy. This law gives attention to the balance between business and public interests. The Act No. 5 /1999 purposes are:

a) To keep the public interest and improve the efficiency of the national economy, as an effort to improve the welfare;

b) To achieve a conducive business climate through the arrangement of fair competition. It will guarantee the equal business opportunities to large, medium and small businesses c) To prevent monopolistic practices and or unfair business competition

d) To create business effectively and efficiency.

Target of the Act No. 5/1999 is all businesses that are individual or business entity, whether incorporated or legal entity that are established and domiciled or conducting activities in Indonesia, either alone or jointly, through the implementation of agreements in various business activities. Based on these provisions, the Act No. 5/1999 applies to all business entities. To oversee the implementation of this Act, government establishes the Business Competition Supervisory Commission (Komisi Pengawas Persaingan Usaha – KPPU). The KPPU is an independent agency ad responsible to the President. The tasks of KPPU are:

a) to conduct an assessment of the agreement;

b) to conduct an assessment of the business activities and or actions of business actors; c) to conduct an assessment of whether there is any abuse of dominant position.

KPPU can take action in accordance with its authority, provide advice to government about policies that are related to monopolistic practices and or unfair business competition, prepare guidelines and or publications that are related to the Act No. 5/1999, and provide regular reports on the work of KPPU to the Indonesian House of Representative.

The important authorities of KPPU are to receive reports, conduct research, carry out the investigation, conclude the result of investigation, call employers, present witnesses, request information from other parties, decide and impose sanctions against business that violate the provisions of Act No. 5/1999.

Competition setting of Act No. 5/1999 can be grouped into several sections. Article 4 to article 16 arranges the agreements which are prohibited. Article 17 to article 24 arrange activities that are prohibited, whereas article 25 to 29 set of dominant position. Enforcement of Act No. 5/1999 is quite dynamic. Many cases have dealt. Today Act No.5/1999 is in process of change for improvement.

2. Malaysia

Malaysia has business competition law since 2010, Malaysia has had laws since 2010, but only implemented it in 2012. Malaysia faces several obstacles to apply. The constraints are political will and public acceptance of competition policy, and lack of human resource and institutions capacity.

practices, despite the ongoing trade liberalization such as AFTA. Husain also argued that Malaysian market scale is small. It causes the number of businesses needed is little. Small and medium enterprises in Malaysian market have limitation of market access and take the economies of scale. These facts – dilemma between competition policy purposes and social economic purposes- make a difficulty for Malaysian government to implement the competition regulation.

Competition act 2010 regulates two main issue, namely Anti-competitive agreement; and Abuse of dominant position. Anti-competitive agreement basically prohibited horizontal and vertical agreement. The Competition act 2010 applies to enterprises, but does not apply to any commercial activity under the legislation specified in the first schedule, i,e, The Communication and Multimedia Act 1998, and The Energy Act 2001. These activities are subject to some competition related provision (ASEAN handbook Competition Policy, 2013).

3. Philippines

Recently Philippines does not have and implement antitrust law and formalize business competition policy. Some of the provisions related to competition policy are applied by government agencies and other entities. Competition framework refers to section 19, article XXII of the Philippines Constitution that said “combination in restraint of trade or unfair competition shall not be allowed”.

Some laws related to competition issues are implemented, such as The Price Act of 1992, The Consumer Act of the Philippines, and The Public Telecommunication Policy Act of the Philippines. In addition, enforcement is also conducted by several agencies. The agencies in the Philippines undertaking the implementation and enforcement of competition laws are (www.tariffcommission.gov.ph/competit.html ):

a) Tariff Commission (TC) – An attached agency of the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA). It is mandated to assist the Cabinet Committee on Tariff and Related Matters (TRM) in the formulation of a national tariff policy and to monitor the implementation of the Tariff and Customs Code (TCC).

b) Bureau of Import Services (BIS) – A staff agency of the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI). It is mandated to monitor import quantities and prices of selected sensitive items (particularly liberalized goods) to anticipate surges of imports and assist domestic industries against unfair trade practices.

c) Bureau of Trade Regulation and Consumer Protection (BTRCP) - Also a staff agency of the DTI. It is mandated to formulate and monitor the registration of business names and the licensing and accreditation of establishments; it also evaluates consumer complaints and product utility failures.

d) Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) – An attached agency of the Department of Finance (DOF). It is mandated to administer corporate government laws such as the approval and registration of corporate consolidations, mergers and combinations. It also implements the Securities Act of 1982 which penalizes fraudulent acts in connection with the sale of securities (e.g. price manipulation, inside trading, short selling, etc).

Until now, the enforcement of antitrust policy in Philippines is poor. Some of the reasons behind the poor enforcement of competition laws:

a) Despite the number of laws and their diverse nature, competition has neither been fully established in all sectors of the economy nor has existing competition been enhanced in other sectors. Since each law is meant to address specific situations, there runs the risk of one law negating the positive effects of another.

c) Fines imposable for breaches of the laws are minimal. Likewise, most punishments are penal in nature; hence, evidence requirements are substantial.

d) There is a lack of jurisprudence and judicial experience in hearing competition cases. e) The SEC regards “efficiency gains” as more important than competition considerations in

mergers and does not have a mandate to challenge mergers unless it can demonstrate they are against the public interest.

4. Singapore

Singapore has had the Competition Act (Chapter 50B) since January 2005. The Act is implemented gradually. Phase I, Competition Commission of Singapore started to work at January 1st, 2005. Phase II, at January 1st, 2006, provision of prohibition of anti-competition agreement and market dominance began to be applied. Provision of prohibition of anti competitive merger is forced after phase II.

Objective of Competition Act (Chapter 50B) (http://app.ccs.gov.sg/) seeks to prohibit anti-competitive activities that unduly prevent, restrict or distort competition. There are three main prohibited activities under the Act:

a) Anti-competitive agreements, decisions and practices (the section 34 prohibition); b) Abuse of dominant position (the section 47 prohibition);and

c) Mergers and acquisitions that substantially lessen competition (the section 54 prohibition). In its administration and enforcement of the Act, the Competition Commission Singapore (CCS) will bear in mind that any regulatory intervention in the market may impose costs. Therefore, the Commission will balance regulatory and business compliance costs against the benefits from effective competition.

Instead of attempting to catch all forms of anti-competitive activities, the Commission's principal focus will be on those that have an appreciable adverse effect on competition in Singapore or those that do not have any net economic benefit. In assessing whether an activity is anti-competitive, the Commission will give due consideration to whether it promotes innovation, productivity or longer-term economic efficiency. This approach will ensure that we do not inadvertently constrain innovative and enterprising endeavors.

Given the wide-ranging industries and markets, CCS will not be able to look into every possible infringement of the Competition Act. It wills priorities its enforcement efforts based on (http:// app.ccs.gov.sg/):

a) potential impact on the economy and society (e g, how significant is the industry in the Singapore Economy, does it have a great impact on business costs in Singapore, how large a consumer base it has, how much will it add to costs of living?);

b) severity of the conduct ( is it hard-core price-fixing, serious abuse of dominance, mergers which substantially lessen competition);

c) Importance of deterring similar conduct (will other companies feel free to engage in the same conduct if it is left unchecked?);

d) Resource considerations (how many cases is CCS handling, how resource intensive is the case relative to the expected benefits?);

e) Risk of over-intervention (when action by CCS may inadvertently deter innovation and risk-taking by businesses).

Singapore Competition Act tends to be based on contestable market philosophy. So the most important condition is the company does not act the monopolistic strategies and practices that will create the welfare loss.

5. Thailand

Indonesia Act. Not all of the business entities subject to TTCA. Central, provincial and local Administration Agency, state owned enterprises, farmer groups, and all business entities under ministerial regulation do not go as TTCA target.

Thailand government creates 3 commissions to run the TTCA that are: (a) Trade Competition Commission (TCC), (b) Sub-committees and Sub-committees investigative, and (c) Appeal Committee. TCC is the government agency that carries out TCCA with 8-12 members. Minister of Commerce is as chairman and Secretary to the Minister of Commerce is as vice chairman. Its members consist of the Secretary to the Minister of Finance lawyers, economists, trade experts, and specialists in business administration and public administration. This commission shall have the power and obligation to consider the complaint, determine rules for dominant business actors, and consider applications for merger permission.

Investigative Sub-committees ad sub-committees are responsible for giving advice, opinions and recommendation to the commission. This investigative committee has the power and right to investigate and inquire about the violation of the competition law. The last committee –Appeal Committee – is responsible for determining the rules and procedures for applicants, etc.

Article 25 of TTCA controls abuse of dominant position, article 26 regulates about merger, whereas article 27 is about collusion, while article 28 and 29 regulate an agreement between domestic and foreign business and unfair trade. All of articles are rule of reason, so it is still possible to discuss and negotiate with commission in case of violation. Nowadays, the Trade Competition Act is under reviewed according to the economy and trade situation aiming to protect competition, to enhance business activities so as to create innovation, and to protect consumer welfare (APEC, 2010).

ANALISYS

As the learning obtained from European Community, we can summarize three key factors of cooperation; which are competition regulation (Act), agency, and legal authority to penalize if infringement happens. The EC does have and also implements all those three properly. However, for AEC case, in spite of the establishment of ACPL, these three factors are still not being constructed.

According to the ASEAN cooperation and competition policy framework and the overview of regulatory system of competition policy in ASEAN countries, it can be examined that in ASEAN level, there is no single policy that can be applied to all country members. Therefore, competition policy implementations in ASEAN region only accommodate its own country level.

Unfortunately, in the case of ASEAN-5, not all of the countries have Competition Act and there is no proper regulation on business competition. Besides, among the countries that already have competition act, each has its own strategy focus and standard. In such conditions, it will be very difficult to do the policy integration, especially for harmonization. There has been no significant development of ASEAN policy harmonization until now although the experts group has been established to develop competition policy, namely AEGC (ASEAN Experts Group on Competition). Yet, it is understandable because the capacity variations between all of the country members are quite high and activities of this institution are still dominated by capacity building, especially for countries that still do not have any competition policy.

From the aspect of agency, since there is no agency for the whole ASEAN countries level, implementations of competition policy are submitted to the agency of each country. Because there is no standardized guidance of it, then it is definitely true that each country has different standard. In addition to the absence of agency in ASEAN level, there is also no court that plays role as adjudicating institution.

a) The presence of several potential ineffective agreements, such as anti-dumping policy. If this is the case, then the benefits for the country over the construction of AEC members will not be optimal, and even more possibly, it could appear as the welfare loss at ASEAN level.

b) The potential emergence of giant monopolist, particularly for multinational industries. Some of negative impacts of giant monopolists and oligopolist are potential welfare loss and economic instability. Giant monopolist and oligopolist will only have positive effect when the market structure follows Bertrand equilibrium or contestable market. But this condition can only be achieved in the case of strict supervision.

Two potential losses would be followed by other several potential losses, and it would eliminate positive impacts of AEC establishment. In order to bring up the three key factors above, SWOT analysis as the analytic method is used to identify the strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat. A. Strength

- The existence of the willingness of ASEAN country members to construct the competition policy, as reflected in the agreement at the ministerial level, or even at the level of heads of state.

- The existence of the willingness of ASEAN countries that do not have competition policy to conduct capacity building by utilizing AEGC.

B. Weaknesses

- There are some of ASEAN members who are less aware of the competition policy. - Lack of political will among country members to harmonize or integrate competition

policy. C. Opportunity

- The existence of successful implementation that can be used as the best practices, namely the European Community.

- The existence of positive interests and supports from international institutions such as WTO.

D. Threat

- The existence of unsuccessful implementation, namely the RECs which only stops at the level of the FTA. Most of the FTAs in general do not integrate their competition policy, or if so, they are in forms of non-binding ones. For example making ASEAN members lead to less the enthusiasm to perform the integration of competition policy.

CONCLUSION

From the description and analysis above, we can conclude some of the followings:

1. Compared to the EU, competition policy within the framework of the AEC has three major drawbacks: regulation (Act), agency, and legal institution to penalize if there is an infringement of business actors in ASEAN level

2. To perform the integration, or even harmonization of the policy, there are some difficulties since some of the ASEAN members have not had any competition policy in the country. Yet, among the countries that already have, they are not standardized at ASEAN level.

3. Theoretically, there are some consequences that may arise in the AEC, when three weaknesses at point 1 are not resolved. They are in the context of potential emergences of welfare loss and giant oligopolists or giant monopolists.

REFERENCES

Adiningsih, Sri and Lestari, Murti. (2007). Competition Aspects of Economic Cooperation in ASEAN Free Trade Area, KPPU, Unpublished Indonesia

ASEAN Economic Community Blue Print, Directorate General of ASEAN Cooperation Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia, 2009.

ASEAN handbook on Competition Policy, 2011. ASEAN handbook on Competition Policy, 2013.

Competition Commission Singapore Competition Philosophy (http://app.ccs.gov.sg/)

Desai, Kiran, and Brown, Mayer. (2010). European Antitrust Review, Global Competition Review, www.wto .org .

European Antitrust Policy, www. ec.europa.eu /competition

GilbertRichard J. Gilbert. (2006). "Competition and Innovation" Issues in Competition Law and Policy. Ed. Wayne Dale Collins. American Bar Association Antitrust Section.

Hoekman, Bernard. (2002). “Competition Policy and Preferential Trade Agreements,” The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A.

Husain, Dato’ Seri Talaat Hj. (2006). Economic Growth and Competition Policy in Malaysia, 2nd

ASEAN Conference on Competition and Law.

Krouse, Clement G. (1990), “Theory of Industrial Economics” First Edition, Bleckwell, Cambridge.

Martin, Stephen. (1994). “Industrial Economics: Economic Analysis and Public Policy” Macmillan Publishing Company, New York.

Martin, Stephen. (2005). “Remembrance of Things Past: Antitrust, Ideology, and the Development of Industrial Economic”, Department of Economics Purdue University, Indiana.

OECD. (2000). International Option to Improve the Coherence Between Trade and Competition Policies, Joint Group on Trade and Competition.

Philippine Competition Law and Policy (www.tariffcommission.gov.ph/competit.html )

Rahutami and Lestari. (2011). The Harmonization Business Competition Regulation ASEAN Economic Community Framework, International Conference Thamkang University, Taiwan

Singapore Competition Act (Chapter 50B) (http://app.ccs.gov.sg/)

Thailand Individual Action Plan (APEC). (2010). www.apec.org/Groups/Economic-Committee/ Competition-Policy-and-Law-Group ) The

Act No. 5/1999, www.kppu.go.id

Tirole, Jean. (1989). “The Theory Industrial Organization”, MIT Press.

Varian, Hal R. (2010). “Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach” Third Edition, WW Norton & Company

Wotoon and Zanardi. (2002). “Trade and Competition Policy: Dumping versus Anti-Trust”1University of Glasgow, Department of Economics, Glasgow G12 8RT, United Kingdom