Fostering Client–Agency Relationships:

A Business Buying Behavior Perspective

J. David Lichtenthal

ZICKLINSCHOOL OF BUSINESS–BARUCHCOLLEGE THECITYUNIVERSITY OFNEWYORK

David Shani

KEANUNIVERSITYAccount acquisition and retention is an ongoing problem facing advertising subsided (Ducoffe and Smith, 1994). Creative consultancies have developed, complementing conventional agencies, while

agencies. Literature in this area has focused on the criteria used in agency

the emergence of media independents reflects the breakdown

selection, the factors fostering continuity, and the forces prompting the

of the agency-commission system (Michell, 1984). Therefore,

break-up of client–agency relationships. However, this classic industrial

the agency’s role as a business service provider demands they

service relationship has not been examined from a business-to-business

must optimally ease the communication between the

adver-buying behavior perspective. A study was conducted with top agency

tiser and agency personnel (Cook, 1989; Tauber, 1986). In

account acquisition personnel. This study found strong support for the

addition, the selling side of agency–client relations has

wit-notion that business buying behavior models can be applied to client–

nessed the creation of positions within agencies that are solely

agency relationships. Furthermore, they may be applied to

business-to-responsible for soliciting new accounts (New York Times, 1990).

business service transactions as well. Many forces considered unique to

Understanding the forces influencing buying behavior for

business buying behavior were prevalent for the selection of agency services

advertising agency services is even more important for

foster-according to sales personnel involved in cultivating new business. The

ing and stabilizing the traditional client–agency relationship.

findings suggest that agencies need to emphasize nonspecific campaign

Historically, the study of this buyer–seller relationship had

forces effecting agency selection. Moreover, the study also points to the

focused predominantly on the target markets of the programs

importance of identifying the effect of internal organizational forces and

themselves and had not been viewed in a business-to-business

the roles buying center members play, side by side with campaign-specific

context. Agencies could incorporate dominant current

prac-factors. Directions for future research are noted and managerial

implica-tices to reflect the fact that clients are likely subject to a myriad

tions for business-to-business new account acquisition and selling are also

of forces affecting organizational buying behavior (Johnston

provided. J BUSN RES2000. 49.213–228. 2000 Elsevier Science Inc.

and Lewin, 1994, 1993; Hutt and Speh, 1998).

All rights reserved.

While researchers have focused on issues relating to agency selection and loyalty in client–agency relationships, they have primarily done so by studying specific organizational or indi-vidual level factors. However, many factors likely influence

A

cquiring and maintaining accounts for advertisingagen-the client–agency relationship. For example, client industry cies has always been important (Aaker, Batra, and

norms and practices and the various roles within client firms Myers, 1996; Russell and Lane, 1996; Wackman,

are instances of factors that are neither organizational nor Salmon, and Salmon, 1987) and crucial to the survival of

individual. What we need is a more comprehensive set of agencies (Beard, 1996; Michell and Sanders, 1995; Michell,

factors that also includes a broader range and variety of envi-Cataquet, and Hague, 1992). The wave of mergers and

acquisi-ronmental and social forces affecting client–agency relations. tions has placed the structure of the advertising industry in

Closer inspection of client–agency relationships shows that a flux and the competitive intensity faced by agencies has not

these are a subset of the organizational buying context. The factors affecting client–agency relations resemble those forces affecting organizational buying behavior (OBB). In the

organi-Address correspondence to Dr. J. David Lichtenthal, Associate Professor of

Marketing, Zicklin School of Business, Baruch College, The City University of zational buying behavior literature there is a dominant and New York, Department of Marketing, 17 Lexington Avenue, New York, NY

10010. Tel: (212) 802-6516. pervasive framework to study the dynamics propelling OBB.

Journal of Business Research 49, 213–228 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0148-2963/00/$–see front matter

In this study, we attempt to provide a richer representation ties of creative teams. Clients view creativity as a more struc-tured process compared with agencies which stressed sponta-of the various forces affecting client–agency relations by

applying a broader and more diverse range of factors likely neity. Successful relationships treat differences in creativity as a matter for positive action prompting the emergence of an affecting the marketing effort for this business service.

The organization of the article is as follows. First, a review account planning function. of the literature on client–agency relations is summarized and

the links to forces affecting business buying behavior is noted.

Loyalty in Client–Agency Relationships

Subsequently, the Webster and Wind (1972a,b) (hereinafter Michell and Sanders (1995) tested a 7-factor 57-item model WW) organizational buying framework was used to identify for predicting account loyalty among advertisers. Regarding a comprehensive list of forces that might affect client–agency overall reasons for agency loyalty, clients ranked actual ac-relationships. An exploratory study was conducted that exam- count characteristics well ahead of the other six dimensions ined the relevance of this list. Implications for future research for remaining loyal. However, items with the highest mean and managing client–agency relations are presented. scores are associated with the general process involving suppli-ers and interpsuppli-ersonal characteristics such as mutual trust, high caliber personnel, and mutual professional competence. They

Literature on Advertising

reaffirm the findings of Michell, Cataquet and Hague (1992)

Client–Agency Relationships

that relate loyalty to campaigns that generate sales, compatiblewith client objectives and the agency’s closeness to their busi-Research in the area of client–agency relations can be classified

ness. The cause of breakups is the absence of these three into three categories: (1) the criteria used by clients in agency

broad aspects. Furthermore, Michell, Cataquet, and Hague selection; (2) the factors fostering continuity of client–agency

(1992) concluded that a prevailing set of variables exists which relations and; (3) the forces prompting the break-up of client–

are responsible for the breakup in agency relationships. These agency relationships. In brief, much of the research has

fo-factors appear consistently over time and between the United cused on how agencies and clients come together, stay together

States and United Kingdom. Termination is a process rather or break up.

than a single decision and that the formal break is related to specific incidents.

Criteria Used in Agency Selection

Agency change could be predicted from a comparison of Cagley (1986) found that perceptions of advertisers and

agen-switchers and non-agen-switchers (Henke, 1995). Compared with cies were equivalent on 14 of 25 selection criteria studied.

non-switchers, primary decision makers who would change Based on attribute mean importance, both groups agreed that

agencies expressed less satisfaction with agency media skills agency personnel should have account responsibility. In

addi-and the size of their account (i.e., energy addi-and attention given) tion, both sides see agency business and management skills

compared with other accounts. Less importance was placed as important attributes. Agency personnel gave more

impor-on creative skills and the agencies’ ability to win awards. tance to “relationship” related attributes than did advertisers.

Creative aspects are important to winning the business and Advertisers, on the other hand, gave less importance to

mar-diminish over time. It appears that agencies overestimate the keting related services supplied by agencies. Self-selection

importance of their creative ability and achievements as the exists, on both sides of this dyad, pointing to the need for

relationship progresses. Thus, there is a need to focus more mutual learning and understanding the other’s viewpoint.

on understanding the unique needs of the client as an “individ-Cagley and Roberts (1984) derived 25 attitudinal

state-ual.” Buchanan and Michell (1991) used linear logistic regres-ments from discussions with agency personnel and published

sion model to measure the association between observable literature. Four factors emerged: market analysis (i.e.,

re-structural factors (i.e., account size-age, past switching behav-search, creativity, media selection); operational scale (i.e., size

ior, agency and client size, product class) in a client–agency of accounts, ability to buy media); interpersonal relations (i.e.,

relationship and the risk of failure (i.e., log-odds of a breakup). compatibility of personnel); veracity (i.e., strength of

recom-Based on more than 1,000 relationships in the United King-mendations and objection to override client ideas). Industrial

dom, they found that larger accounts are more stable even if advertisers feel a stronger need for sales promotion ideas and

due to shared association. In addition, new accounts may be capability.

less prone to failure while a higher incidence of prior switching Perceptions of creativity are a source conflict in client–

behavior is positively related to subsequent switching behav-agency relations, among the top managements of the 50 largest

ior. Organizational factors are the more important structural advertising agencies and advertisers (Michell, 1984). Both

factors for determining relationship stability. sides agreed on the primary importance of the client–agency

Clients and agencies do try to match up with similar part-relationship. However, the differences in the remaining four

ners as to client, size, agency size, and account size (Michell, categories studied was pronounced. The clients saw

“creativ-1988). Major clients remain loyal to larger agencies, in part ity” as an interorganizational and a process phenomenon while

rein-215

Client–Agency Relationships J Busn Res

2000:49:213–228

vigorate the account. Major accounts are comparatively more the top 100 advertisers and the account executives who man-age the accounts. The research goal was to detect sources of loyal despite account size preferring continuity. However,

there has been a polarization in client choice of agency type dysfunctional behavior and learn the extent to which each side is in concord with the other’s shortcomings. The main (Michell, 1984). The largest agencies maintain their net

posi-tion through adaptaposi-tion of services provided. Movement has factors derived from specific contributory areas include: per-sonnel turnover at the agency, assistance given to the agency been away from agencies with higher marketing reputations

toward agencies with higher creative reputations. A clear trend by the advertiser, client organization effectiveness with its advertising activities, and degree of agreement (on both sides) exists toward the use of media consultants. Three declining

sectors are medium and small size agencies and in-house about the agency’s role. An inverse relationship exists between high turnover at the agency and their effectiveness in handling direct accounts. Small agencies have declined at a faster rate.

Doyle, Corstjens, and Michell (1980) study the matched the account. The client must monitor the quantity and quality of assistance it is offering its agency and its own effectiveness in views of companies that switched with those of their former

agency. They identify different perceptions of the reasons for advertising decision making. Agency and advertiser personnel agree on the role the agency is to play in the client’s marketing the breakdown. The primary reason for the account move,

from the agencies’ perspective, is changes in client policy plan. Both sides must present what they expect to put into the business relationship to reduce conflict.

while from the client’s perspective, dissatisfaction with agency

performance is foremost. Furthermore, the breakdown is a In summary, we can observe that past research on client– agency relationships suggests factors that resemble those forces process of creeping disengagement preceded by clear signs of

vulnerability. affecting OBB. Specifically, some criteria used in agency

selec-tion can be classified as mainly individual level factors resem-bling the more micro-forces affecting OBB. Factors such as

Forces Prompting Break-up

mutual learning and perceptual incongruence are used and

of Client–Agency Relationships

are present in WW. Among the factors affecting loyalty in Murphy and Maynard (1996) explored cognitive conflict

be-client–agency relations are interpersonal characteristics such tween agencies and clients comparing decision profiles

regard-as mutual trust and professional competence (Michel and ing hypothetical campaigns in five areas. While substantially

Sanders, 1995). As well, organizational characteristics such in overall agreement with their clients, agency rankings on

as size noted by Buchanan and Michel (1991) and Michel the five decision areas did show some discrepancies. Agency

(1988) plus changes in client policy (Doyle, Corstijens, Mi-professionals agreed with clients on the importance of

mes-chell, 1980). Some of the forces prompting the break-up of sage/creativity and then budget. Media planning was third,

client–agency relationships are similar to those forces affecting while strikingly they gave less weight to market research and

OBB. In particular, Murphy and Maynard (1996) and Hotz the client/agency relationship. These latter discrepancies were

et al. (1982) emphasized the effects of organizational factors not surprising, as it is expected that clients will worry about

with the interaction of individual factors. This interaction is product development and agencies worry about relationships.

suggested by WW. Beard (1996) called attention to the influ-While using pooled data from both groups could obscure

ence of group forces in the form of role ambiguity and its individual differences, cognitive disagreement appears to be

impact on sustaining client satisfaction. In the background, ruled out as a source of conflict. The results, according to

these research streams makes the tacit assumption of an OBB the authors, point to interpersonal factors and organizational

context. deficiencies that might cause both groups to perceive poor

communication and misunderstanding. Agencies and clients

think alike but often believe they do not.

The Business Buying

Effects of client representative role ambiguity could be

Behavior Perspective

found along several dimensions. For task-interactive serviceslike agency use, a positive relationship exists between experi- Prior literature on agency–client relations has not looked at enced role ambiguity and the client’s job tension-anxiety and the broad forces affecting organizational buying dynamics of perceptions of conflict in agency relations (Beard, 1996). An clients and the implications for agency marketing effort. Zei-inverse relationship exists between role ambiguity and the thaml, Varadarajan, and Zeithaml (1988) suggest research on client representatives’ tenure/experience, time working with the contextual relevance of buyer behavior variables holds the an agency, and client satisfaction with the agency. Client role potential for major contribution to the execution of marketing ambiguity has significant impact on four relationship conse- strategy.

Webster and Wind (1972 a,b). These frameworks have shaped of these articles did not directly cite WW, it apparently acts as a “background gestalt” for selecting and developing mea-our understanding of organizational buying behavior since

sures for research on OBB. Furthermore, the incidence of the 1960s (Hutt and Speh, 1998; Wilson, Lichtenthal, and

citation, for the WW framework in the Social Science Citation Rethans, 1986; Johnston, 1981). A brief overview of each is

Index (SSCI) for the first 20 years after its publication (i.e., provided.

a census from 1972–1991), reveals that the Webster and Wind Robinson, Faris, and Wind (1967) developed a process

(1972b) article was cited 37 times. Researchers relied on WW model known as the BUYGRID framework from descriptions

in selecting variables in empirical work eight times (22%). In of three purchase situations. The BUY CLASSES element (i.e.,

the remainder, WW was used to discuss buying center roles straight rebuy, modified rebuy, new task) has guided research

11 times (30%), to refer to comprehensive models seven times that helped empirically derive the classification of business

(19%), to refer to the process of OBB four times (11%), to buying situations altering the duration of the organizational

note the complexity of OBB twice (5%), to discuss the need buying process. The BUY PHASES element has guided

re-for certainty and risk reduction twice (5%), and re-for other searchers who have empirically derived variations on the total

purposes (8%). The WW framework is widely recognized as number of stages and their order in the buying process

(Lich-a set the forces (Lich-active on the buyer’s side th(Lich-at could be used tenthal, 1988; Johnston, 1981).

for developing a characterization of business buying behavior. Sheth (1973) developed an organizational level framework

In the study described below, the WW framework with its on the process of organizational buying based on case studies

distinct subdivision of four sets of forces into E,O,G,I, is and literature reviews. Three elements emerged: a

psychologi-applied to the client–agency context. It will become apparent cal world of the decision maker, the conditions that precipitate

that this framework enriches our understanding of this buyer– joint decision making and the process of conflict resolution.

seller relationship as well. The variables and their linkages are suggested including

situa-tional factors. Choffray and Lilien (1977), drawing on the

conceptual work of Sheth (1973) and Webster and Wind

Methodology

(1972a), develop an empirical model. They focus on the links

Developing Measures of the Forces

between characteristics of the organization’s buying center

and three major stages in the organizational buying process. To identify a set of forces likely to be active in affecting They developed an operational model of OBB that explicitly buying behavior for services, appropriate measures must be addresses the output of group decision making by giving a developed. Hambrick (1984) suggested the use of an existing conceptual framework, measures and methodology for pre- framework to guide in the derivation of measures for collecting

dictive purposes. data. For example, Bunn (1993a) developed a taxonomy of

The most comprehensive and influential framework is that buying patterns and situations consisting of six prototypical proposed by Webster and Wind (1972 a,b). Using case studies buying decision approaches based on numerically derived and literature reviews, WW heuristically derived a structure patterns similar to previous classification schemes with some of the set of four forces influencing OBB (Appendix A). modifications.

Their original conceptualization of the forces shaping OBB In this study, the chapters on environmental, organiza-is described as a general theory of OBB. Four classes of forces tional, group, and individual forces (Webster and Wind, are seen to act in OBB: environment (E), organization (O), 1972b, pp. 40–117) were studied to derive the content of the group (G), and individual (I). A limitation of their approach, items for the instrument. A list of statements was developed as with most complex models, is that relationships among to capture as many distinct aspects of each force as possible. these forces and operationalization procedures were not well Following Bailey (1994) and Hunt (1983), the statements specified. WW proposed that environmental forces external were made to be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaus-to the firm provide a subtle and pervasive context in which tive. These statements are listed in Table 1.

217

Client–Agency Relationships J Busn Res

2000:49:213–228

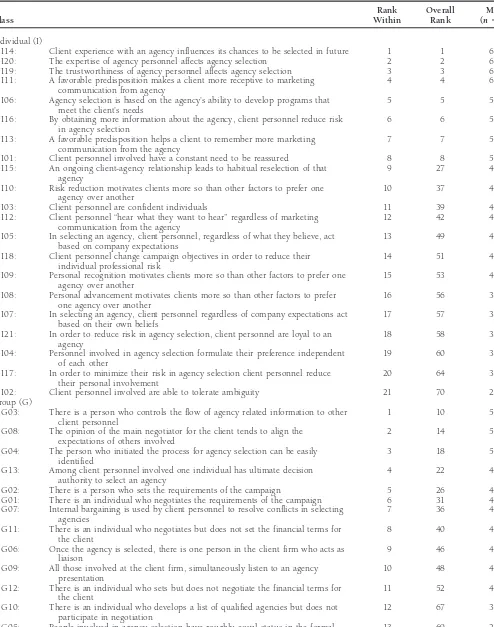

Table 1. Rank and Mean Frequency of Each Item by Major Class

Rank Overall Mean

Class Within Rank (n597)

Individual (I)

I14: Client experience with an agency influences its chances to be selected in future 1 1 6.40

I20: The expertise of agency personnel affects agency selection 2 2 6.30

I19: The trustworthiness of agency personnel affects agency selection 3 3 6.13

I11: A favorable predisposition makes a client more receptive to marketing 4 4 6.05

communication from agency

I06: Agency selection is based on the agency’s ability to develop programs that 5 5 5.97

meet the client’s needs

I16: By obtaining more information about the agency, client personnel reduce risk 6 6 5.96

in agency selection

I13: A favorable predisposition helps a client to remember more marketing 7 7 5.89

communication from the agency

I01: Client personnel involved have a constant need to be reassured 8 8 5.56

I15: An ongoing client-agency relationship leads to habitual reselection of that 9 27 4.76

agency

I10: Risk reduction motivates clients more so than other factors to prefer one 10 37 4.50

agency over another

I03: Client personnel are confident individuals 11 39 4.45

I12: Client personnel “hear what they want to hear” regardless of marketing 12 42 4.32

communication from the agency

I05: In selecting an agency, client personnel, regardless of what they believe, act 13 49 4.20

based on company expectations

I18: Client personnel change campaign objectives in order to reduce their 14 51 4.07

individual professional risk

I09: Personal recognition motivates clients more so than other factors to prefer one 15 53 4.04

agency over another

I08: Personal advancement motivates clients more so than other factors to prefer 16 56 3.89

one agency over another

I07: In selecting an agency, client personnel regardless of company expectations act 17 57 3.85

based on their own beliefs

I21: In order to reduce risk in agency selection, client personnel are loyal to an 18 58 3.69

agency

I04: Personnel involved in agency selection formulate their preference independent 19 60 3.56

of each other

I17: In order to minimize their risk in agency selection client personnel reduce 20 64 3.34

their personal involvement

I02: Client personnel involved are able to tolerate ambiguity 21 70 2.42

Group (G)

G03: There is a person who controls the flow of agency related information to other 1 10 5.54

client personnel

G08: The opinion of the main negotiator for the client tends to align the 2 14 5.22

expectations of others involved

G04: The person who initiated the process for agency selection can be easily 3 18 5.05

identified

G13: Among client personnel involved one individual has ultimate decision 4 22 4.97

authority to select an agency

G02: There is a person who sets the requirements of the campaign 5 26 4.76

G01: There is an individual who negotiates the requirements of the campaign 6 31 4.68

G07: Internal bargaining is used by client personnel to resolve conflicts in selecting 7 36 4.53

agencies

G11: There is an individual who negotiates but does not set the financial terms for 8 40 4.40

the client

G06: Once the agency is selected, there is one person in the client firm who acts as 9 46 4.28

liaison

G09: All those involved at the client firm, simultaneously listen to an agency 10 48 4.24

presentation

G12: There is an individual who sets but does not negotiate the financial terms for 11 52 4.06

the client

G10: There is an individual who develops a list of qualified agencies but does not 12 67 3.07

participate in negotiation

G05: People involved in agency selection have roughly equal status in the formal 13 69 2.70

organizational hierarchy

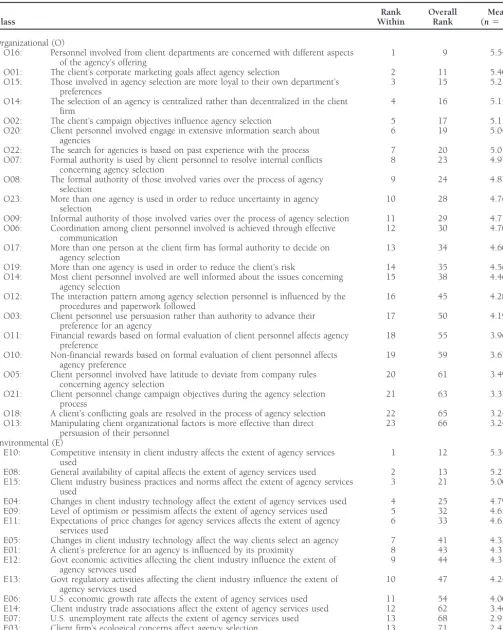

Table 1. continued

Rank Overall Mean

Class Within Rank (n597)

Organizational (O)

O16: Personnel involved from client departments are concerned with different aspects 1 9 5.54

of the agency’s offering

O01: The client’s corporate marketing goals affect agency selection 2 11 5.40

O15: Those involved in agency selection are more loyal to their own department’s 3 15 5.21

preferences

O14: The selection of an agency is centralized rather than decentralized in the client 4 16 5.15

firm

O02: The client’s campaign objectives influence agency selection 5 17 5.11

O20: Client personnel involved engage in extensive information search about 6 19 5.04

agencies

O22: The search for agencies is based on past experience with the process 7 20 5.01

O07: Formal authority is used by client personnel to resolve internal conflicts 8 23 4.97

concerning agency selection

O08: The formal authority of those involved varies over the process of agency 9 24 4.87

selection

O23: More than one agency is used in order to reduce uncertainty in agency 10 28 4.76

selection

O09: Informal authority of those involved varies over the process of agency selection 11 29 4.71

O06: Coordination among client personnel involved is achieved through effective 12 30 4.70

communication

O17: More than one person at the client firm has formal authority to decide on 13 34 4.60

agency selection

O19: More than one agency is used in order to reduce the client’s risk 14 35 4.56

O14: Most client personnel involved are well informed about the issues concerning 15 38 4.46

agency selection

O12: The interaction pattern among agency selection personnel is influenced by the 16 45 4.28

procedures and paperwork followed

O03: Client personnel use persuasion rather than authority to advance their 17 50 4.19

preference for an agency

O11: Financial rewards based on formal evaluation of client personnel affects agency 18 55 3.96

preference

O10: Non-financial rewards based on formal evaluation of client personnel affects 19 59 3.63

agency preference

O05: Client personnel involved have latitude to deviate from company rules 20 61 3.49

concerning agency selection

O21: Client personnel change campaign objectives during the agency selection 21 63 3.37

process

O18: A client’s conflicting goals are resolved in the process of agency selection 22 65 3.24

O13: Manipulating client organizational factors is more effective than direct 23 66 3.24

persuasion of their personnel Environmental (E)

E10: Competitive intensity in client industry affects the extent of agency services 1 12 5.34

used

E08: General availability of capital affects the extent of agency services used 2 13 5.27

E15: Client industry business practices and norms affect the extent of agency services 3 21 5.00

used

E04: Changes in client industry technology affect the extent of agency services used 4 25 4.79

E09: Level of optimism or pessimism affects the extent of agency services used 5 32 4.65

E11: Expectations of price changes for agency services affects the extent of agency 6 33 4.62

services used

E05: Changes in client industry technology affect the way clients select an agency 7 41 4.32

E01: A client’s preference for an agency is influenced by its proximity 8 43 4.31

E12: Govt economic activities affecting the client industry influence the extent of 9 44 4.31

agency services used

E13: Govt regulatory activities affecting the client industry influence the extent of 10 47 4.24

agency services used

E06: U.S. economic growth rate affects the extent of agency services used 11 54 4.00

E14: Client industry trade associations affect the extent of agency services used 12 62 3.46

E07: U.S. unemployment rate affects the extent of agency services used 13 68 2.91

E03: Client firm’s ecological concerns affect agency selection 13 71 2.42

219

Client–Agency Relationships J Busn Res

2000:49:213–228

also be deemed not as important by some respondents. To over, choosing a new advertising agency is a high involvement minimize the halo effect of continuously evaluating items from (new task) decision for the organizational buyer (Webster, one major OBB force and to guide respondents to give careful 1990). The process of choosing an agency involves many and equal consideration to all the forces two steps were taken: individuals over a substantial period of time increasing the (1) the poles of the scales were alternated throughout the likelihood of the maximum number of forces being active and instrument; and (2) the items were systematically rotated. experienced by sales representatives. Therefore, the senior These two steps help ensure that sales executives would give sales personnel of such agencies likely accumulate knowledge their assessments on a set of measures that is a proxy for the and experience on the buying behavior of various organiza-entire WW framework without signaling its broad content or tions. Campbell (1955) proved that knowledgeable people,

structure. when answering well-designed questionnaires within their

Senior sales personnel from the top 50 agencies in the area of expertise, provide quality data. More recently, Weitz, Eastern United States were selected fromAdweek Agency Direc- Sujan, and Sujan (1986) stress salesperson knowledge with tory.Thirty-nine of the fifty firms initially contacted by phone an ability to process buyer information as a determinant of agreed to participate. Eleven refused citing reasons of confi- selling success.

dentiality. Each agency that agreed accepted 10 questionnaires Senior sales personnel, like account supervisors, are typi-with postage-paid return envelopes and circulated these to cally responsible for convincing the potential client to select their sales executives responsible for new account develop- one agency over another, while account executives are respon-ment. To foster participation, guaranteed anonymity was sible for servicing and satisfying the client once on board. It promised and respondents were not required to identify them- is the account supervisor’s job to know and understand the selves or their firm. A total of 101 usable surveys were re- needs and requirements that shaped the clients’ selection of the turned, yielding a response rate of 25.8% based on the number agency. They must understand their clients’ buying behavior.

of surveys distributed. When respondents are asked about specific purchases they

have participated in, it may restrict the ability to generalize the results (Kohli, 1989; Silk and Kalwani, 1982 in Bunn

Selecting Key Informants

1993a). Therefore, sales executives were asked to recall theirTo ascertain the active forces affecting OBB for business ser- most recent selling experiences rather than a decision instance. vices, it is important to use respondents who may have knowl- Data was collected from sales supervisory personnel believed edge about business buying behavior in a broad range of to possess experience and knowledge about a variety of organi-business markets (Silk and Kalwani, 1982; Bunn, 1993; Kohli, zations using agencies’ services.

1989). According to Bunn (1993a) early research relied on the use of key informants from the buying side (i.e., purchasing

managers’ reports of their own behavior and the behavior of

Data Analysis

others involved), and it evolved to include informants fromThe data was analyzed in several steps. First, the sample was the selling side (i.e., sales representatives and sales managers).

examined to assess respondent profile and experience. Second, Earlier, Moss (1979) had reported three case studies wherein

all 72 items were examined to establish the extent of occur-industrial sales personnel were effectively used as a source of

rence of the OBB forces. The pattern of groupings within each in-depth marketing intelligence about buyers.

of the four main classes was explored as well. Finally, the Researchers have not used reports on industrial buying

derived framework was examined using all 72 items and com-behavior from sales executives frequently, and these reports

pared with the proposed structure of the WW framework. should be considered valid sources of information about OBB.

The pattern of groupings among the four main classes was As an observer external to the buying firm, sales personnel

also examined. should be able to see the broader set of forces affecting the

OBB process (Anderson, Chu, and Weitz, 1987). Furthermore,

Respondent Profile and Experience

organizational buyers have been shown to hold perceptual

The confidence that can be placed in the results is in part views skewed to favor their own importance and functional

contingent upon the characteristics of the respondents as key positions in the organization (Silk and Kalwani, 1982). In

informants. An examination of the respondent’s job title, sales effect, organizational actors are unable to “step out of” their

experience, and their industry exposure as shown by their context and location within the firm to obtain a view including

account activity was conducted. more macro forces. Furthermore, “snowballing techniques”

As a group they have considerable experience. On average, For all 60 items surviving there were at least 97 least usable cases (except one item with 91) even after listwise deletion. the respondents have been in the advertising business 11.15

years (n 5 96), with their current agency 5.21 years (n 5 A 2.0 or higher on a semantic scale suggests that the force is somewhat active. A 3.5 is theoretically the number at which 98), and in their current positions 3.56 years (n597).

The external validity of the framework that emerges is the respondent group finds this force more active than not. The full range of the 1–7 scale was used for every item included partly contingent upon the respondent’s breadth of experience

in converting prospective consumers of agency services to in the analysis. These procedures were used to lower the likelihood of spurious factors or items remaining or being clients. In an open-ended format, the respondents reported

the three industries or firms with which they most frequently developed.

Table 2 shows the results from the four separate factor did business. While information concerning each agency’s

clients is publicly available, the experience of individual sales analyses conducted on each of the set of items from main forces (i.e., E,O,G,I).

executives could vary. The responses showed that 65

indus-tries were represented at the level of detailed industry (4-digit For each of the major four categories, the table shows (1) the framework proposed by WW; (2) the derived structure SIC code), 53 at the industry group level (3-digit SIC code),

and 30 at the major group level (2-digit SIC code). The distri- based on the factor analyses; (3) the cumulative variance for an force; (4) the extent to which the numerically derived bution was flat, with no one industry predominant. Overall,

the respondent group is well qualified as key informants, given structure corresponds to the WW framework; and (5) a sum-mary of findings for each force. A discussion of the main their organizational positions, years of experience and breadth

of industry exposure. findings follows.

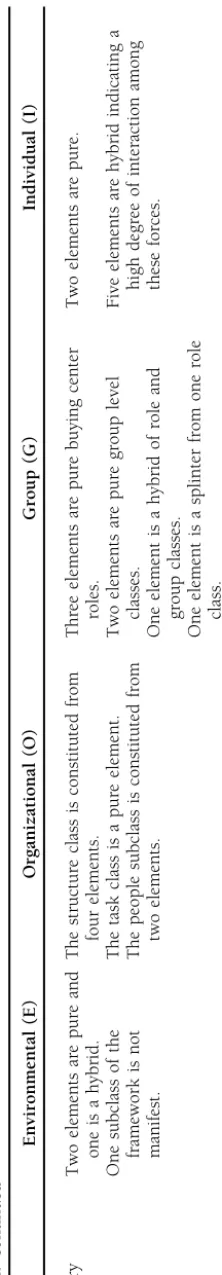

In the environmental class, EF1 and EF2 correspond to the technological and economic subclasses as specified in

Main Classes of Forces Affecting OBB

WW. EF3 is a hybrid of legal and political subclasses. EF4 is The respondents were required to assess the extent to which

a hybrid of cultural and economic (industry) conditions. The the specified OBB items from the WW framework are affecting

physical environment does not appear to be active probably their clients’ buying behavior. Table 1 contains the summary

because of the study’s urban location. In the organizational of the means of the 72 items. Each item was scored on a scale

class, the eight factors derived use all the items from the of 1 (never) to 7 (always). Items were considered significantly

organizational class as suggested by WW. In the group class, active for characterizing buying behavior, if they ranked above

six factors are derived. Four correspond to four of the five a cut-off level across all respondents of above 3.5. Of the 72

original buying center roles. There was some role fracturing items derived, 60 (83.3%) have a mean extent of occurrence

(i.e., hybrid roles). Respondents indicated that the number of greater than 3.5. Respondents found these items to be more

people typically involved from the client firm during the buy-active than not in their clients’ buying behavior.

ing process averages 5.45, with a standard deviation of 1.878 In their chapters devoted to the four main forces, Webster

(n5 95). Other studies also empirically establish that OBB and Wind, (1972b, p. 40–107) emphasized the interaction

is a multi-person phenomenon (Silk and Kalwani, 1982; Mori-within each class. Factor analysis is preferred to cluster analysis

arty and Bateson, 1982). One factor corresponds to a negotia-in this situation because, from a theoretical standponegotia-int, WW

tion role and one to the manifestation of lateral relationships. already contains loosely specified classes and plausible

group-In the individual class all seven factors derived correspond ings (Stewart, 1981). Because cluster analysis is a theoretically

to the individual subclasses as specified by WW. Five were unbounded numerically driven procedure, it is less

appro-hybrid. priate. Exploratory factor analysis allows any patterns (i.e.,

on an intra-class and inter-class basis) to emerge within the

Underlying Structure of the Forces Effecting OBB

theoretical bounds of the WW framework.

Similar to Moncrief’s (1986) use of factor analysis to de- The research purpose is to investigate the general structure of the framework that emerges, and to explore the nature of velop a sales position taxonomy, the following procedures

were used for all factor analyses performed in this study: the interactions among the OBB classes. First, it was to be determined if there is a distinction between the external and (1) consideration was given to any factor initially extracted

(principle components method) with an eigen-value greater internal classes. Webster and Wind (1972b, p. 40) noted that “Environmental influences are subtle and pervasive. They are than 1.0; (2) all those factors were subject to varimax rotation;

(3) items included had a loading of 0.40 or greater. This cut- hard to identify and describe, and they provide the context within which organizational, group, and individual factors in off level was chosen based on a visual examination of all

loadings that revealed a significant drop in the loadings below turn exert their influence.” Therefore, the items that represent the environment, which is external to the buying organization, 0.40; (4) any item with cross-loading of 0.40 or higher on

more than one factor was deleted; (5) as mentioned previously, should group together, while the organizational, group, and individual items should exhibit a higher degree of interaction. items with a mean extent of occurrence of 3.5 or below were

221

Client–Agency

Relationships

J

Busn

Res

2000:49:213–228

Table 2. Factor Analyses on Main Forces

Environmental (E) Organizational (O) Group (G) Individual (I)

Original WW Cultural Goals and Tasks Gatekeeper, User, Buyer, Decider, Personality

Framework Influencer

Economic Structure (communication, status, Tactics of Lateral Relationship Role Set authority, rewards, workflow)

Legal Technology Social negotiations Motivation Physical People Performance of Buying Committee Learning Process

Political Interaction with Environment

Technology Preference Structure

Decision Rules

Empirically Derived EF1 Technology effects the OF1 Authority of those involved varies GF1 Negotiator sets financial terms and IF1 Process-results of learning about Structure extent and way agency and is used to resolve conflict selects vendors the agency

services are used

EF2 Economic conditions vis- OF2 Marketing and campaign goals GF2 Liaison-flow of information IF2 Confidence in agency a-vis monetary policy and

anticipated price changes

EF3 Legal and political forces OF3 Communication and information GF3 Determines requirements IF3 Self-aggrandizement government - regulatory search

ativity

EF4 Business practices and OF4 Risk-uncertainty reduction GF4 Opinion leader-ultimate authority IF4 Risk reduction competitive intensity through multiple sourcing

OF5 Different people decide about GF5 People involved are of equal IF5 Independent thinking about agency different aspects of offering status and they bargain selection

OF6 Selection process is centralized GF6 Initator role IF6 Straight rebuy tendency

OF7 Participants are loyal to their IF7 Insecurity and selective perception department’s preferences than those

of other departments

OF9 Financial rewards based on personal evaluation effects selection

Cumulative variance 55.5% 58.1% 56.2% 60.0%

Degree of EF1 and EF2 corresponds to OF1 corresponds to authority structure GF1 is the buyer’s role IF1 is hybrid from learning and correspondence economic and technological preference structure

forces

EF4 is a hybrid of culture and OF2 & OF6 constitutes goals and GF2 is the gatekeeper’s role IF2 is a hybrid of personality, economic forces tasks motivation and preference classes The physical environment OF3 corresponds to communication and GF3 is hybrid of de facto decider and IF3 is a hybrid of motivation and

taxon is not active workflow structure buying center listening to presentation perceived risk classes

OF4 corresponds to behavioral theory GF4 corresponds to social negotiation IF4 is constituted from the motivation

of the firm class

OF5 & OF7 constitutes the buying GF5 corresponds to lateral relationships IF5 is a hybrid of personality and role

center as a group set

OF9 corresponds to reward structure GF6 is a role splintered from the user IF6 is a hybrid of role expectations and class learning classes

IF7 is constituted from personality

organizational and individual classes should interact with each other to a higher degree than they do with the group class: “. . . individual and organizational goals combine in a unique way to determine a frame of reference or a point of view that guides each individual and determines their interpretation of the behavior of other members of the buying center” (Webster and Wind, 1972b, p. 80). Therefore, for pairwise interactions of O,G,I class items the O-I combination should exhibit the highest degree of interaction.

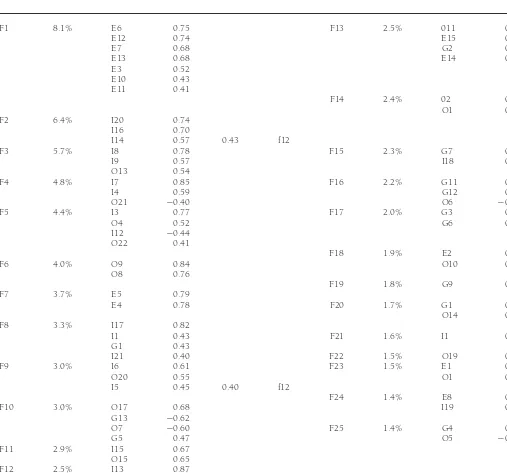

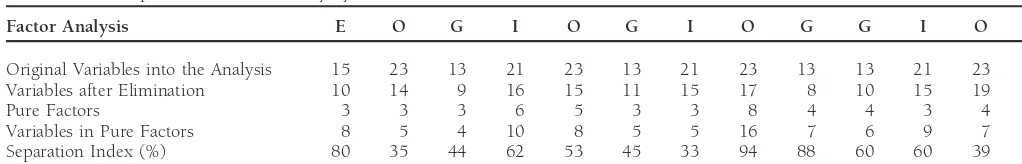

FACTOR ANALYSIS OF ALL ITEMS SIMULTANEOUSLY. To ex-plore the pattern of groupings among all the major classes, an exploratory factor analysis on all 72 items simultaneously was performed. A total of 65 items forming 25 factors survived the procedure outlined earlier (Table 3).

There are three pure environmental factors. F1 represents the macro and the industry environment. F7 captures the effect of the technological environment, and F23 reflects the geographic proximity of the agency. These environmental fac-tors are meaningful and not contaminated with items from the other three major classes. The remaining factors consist of a mix of items from the other three classes. Therefore, the WW hypothesized broad distinction between E and O,G,I emerged from the data.

An Item Separation Index (ISI) was developed specifically for detecting mutual exclusivity of classificational schemes. A basic requirement for good classification schemes is mutual exclusivity (Bailey, 1994; Hunt, 1983). The ISI is a relative measure of the mutual exclusivity of the various classes (i.e., the four sets of OBB forces). The index ranges in value between 0 and 100. A high value of the ISI suggests that the items belonging to a particular class load together and do not to interact with other classes. A low value of the ISI suggests that the items from one class interact with items from another; therefore, the classes are not mutually exclusive. This index is sensitive in that even one contaminating item in a factor will show interaction. In addition, only nearly pure factors will drive the index to high values.

The ISI was calculated as follows: (1) the “pure factors” were identified (i.e., those consisting exclusively of E or O or G or I items); (2) for each of the major classes, the number of items in the pure factors were summed; (3) for each of the four forces, the number of the items from step 2 were divided by the total number of items that survived the screening for that main class (i.e., E,O,G, or I, respectively); (4) that number was multiplied by 100. The resulting percentage and summary of the interaction among the items for the analysis of E,O,G and I is given in Table 4.

The environment class has an ISI value of 80, while the values for the organization, group and individual force factors are 35, 44, and 62, respectively. The high ISI value for the environmental force factors indicates that E items group to-gether to create a relatively pure class. The lower ISI values for the other three forces suggests that items from those classes

Table

ex-223

Client–Agency Relationships J Busn Res

2000:49:213–228

Table 3. Factor Analysis for All Forces (E, O, G, I)

F1 8.1% E6 0.75 F13 2.5% 011 0.66

E12 0.74 E15 0.50

E7 0.68 G2 0.49

E13 0.68 E14 0.47

E3 0.52

E10 0.43

E11 0.41

F14 2.4% 02 0.78

O1 0.50

F2 6.4% I20 0.74

I16 0.70

I14 0.57 0.43 f12

F3 5.7% I8 0.78 F15 2.3% G7 0.74

I9 0.57 I18 0.60

O13 0.54

F4 4.8% I7 0.85 F16 2.2% G11 0.82

I4 0.59 G12 0.55

O21 20.40 O6 20.43

F5 4.4% I3 0.77 F17 2.0% G3 0.85

O4 0.52 G6 0.50

I12 20.44

O22 0.41

F18 1.9% E2 0.81

F6 4.0% O9 0.84 O10 0.47

O8 0.76

F19 1.8% G9 0.79

F7 3.7% E5 0.79

E4 0.78 F20 1.7% G1 0.78

O14 0.63

F8 3.3% I17 0.82

I1 0.43 F21 1.6% I1 0.86

G1 0.43

I21 0.40 F22 1.5% O19 0.87

F9 3.0% I6 0.61 F23 1.5% E1 0.75

O20 0.55 O1 0.44

I5 0.45 0.40 f12

F24 1.4% E8 0.73

F10 3.0% O17 0.68 I19 0.45

G13 20.62

O7 20.60 F25 1.4% G4 0.84

G5 0.47 O5 20.41

F11 2.9% I15 0.67

O15 0.65

F12 2.5% I13 0.87

I11 0.52 0.42 f2

cluding the items that constitute the environmental class. G as proposed in the WW framework. However, an interaction Nineteen factors and 41 associated items survived the screen- clearly exists. Further insight can be gained into the pattern ing procedure for all O,G,I items. These additional ISI values of interaction by looking at all pairwise interactions of O, G for O,G,I are 53, 45, 33, respectively. These low ISI numbers and I classes.

indicate that these classes are not mutually exclusive.

PAIR-WISE FACTOR ANALYSIS. To explore patterns of interac-The ISI values do not provide a clear indication of the

tion among O, G, and I, factor analyses were performed on pattern of interaction. An examination of the factor analysis

all pair-wise combinations of the items that constitute these revealed that of the 19 factors, 10 were “pure” (i.e., these

three classes (i.e., G and O, G and I, O and I). Table 4 shows were items from only one of the three remaining classes) and

their ISI values under G O, G I, and O I. For G-O, the ISI nine were mixed [i.e., three (0,I), two (I,G), two (G,O), and

values for G and O are 94 and 88, respectively. Of a total of one (G,O,I) hybrid factor]. Thus, O,G,I simultaneously

Table 4. Item Separation Index Summary by Class

Factor Analysis E O G I O G I O G G I O I

Original Variables into the Analysis 15 23 13 21 23 13 21 23 13 13 21 23 21

Variables after Elimination 10 14 9 16 15 11 15 17 8 10 15 19 19

Pure Factors 3 3 3 6 5 3 3 8 4 4 3 4 3

Variables in Pure Factors 8 5 4 10 8 5 5 16 7 6 9 7 8

Separation Index (%) 80 35 44 62 53 45 33 94 88 60 60 39 40

consist exclusively of group items, and one is hybrid. These lieved to affect business-to-business buying behavior. Because high ISI values indicate a high degree of separation. This the range of forces was broad, measures had to be taken on finding mirrors WW’s proposed structure of mutually exclu- a organizational level rather than on a individual level. As sive for these two main forces. For G-I, the ISI of 60 for G well, using the WW framework results in using an item base and 60 for I suggests a higher degree of interaction compared that may be lacking some content for each of the four forces. to G and O. Of the 10 factors that emerged, four consist Further conceptualization on these forces are needed. This exclusively of individual items, three consist exclusively of study was conducted among the top 50 advertising agencies group items, and the remaining three are mixed. For O-I, the in a major metropolitan area. The sample was based on the ISI values for O and I are 38 and 40, respectively. This indicates perceptions of buying behavior experienced by sales personnel the strongest interaction among the three pairs of classes. Of of the largest 50 advertising agencies. This may limit the a total of 14 factors, three consist of pure individual items, generalizability of the findings and suggest the need for re-four consist exclusively of organizational items, and eight are search on other services as well as additional populations. from both. The low ISI values suggest the highest interaction

among these two. This lack of mutual exclusivity supports

Discussion and Implications

the relationship proposed in the WW framework.

Contextual knowledge possessed by sales representatives has

Interlude

been shown to facilitate the personal selling effort by enablingsales personnel to accurately categorize buyers and situations, Most of the OBB items (60 out of 72) extracted from the WW

based on past experience. Prior research efforts have addressed text were found to influence the buying decision for agency

recovered contextual knowledge through the use of self-report selection. That respondents were able to comprehend and

data and its value in the personal selling effort (Weitz, 1981, report that the WW framework, as represented through the

1978). The present study took a different approach by present-72 items occurs with relatively high frequency, leads to three

ing to sales personnel a well-developed list of possible contex-important conclusions. First, the status of WW’s framework

tual knowledge items derived from a widely accepted and is holistically affirmed. Furthermore, this study establishes the

intuitively appealing theoretical model of OBB. To the extent applicability of WW to industrial service transactions. Second,

that the general model captures organizational buying forces it appears that qualified “external observers” in a business

faced by sales personnel on a day-to-day basis some conver-buying transaction possessed more depth and breadth of

gence between their experience and the model should be knowledge about OBB than is generally believed. Third, by

realized. describing the WW forces in language reflecting the key

infor-Respondents were most likely not familiar with the WW mant’s particular industry, it is possible to access this

knowl-general model by name or content. Therefore, the model as edge. These are encouraging indications for future research.

represented through a set of items was nominally transparent. Some of the problems raised in conducting empirical research

That respondents were able to comprehend and experience concerning OBB at a more macro level can be overcome.

most of these 72 items with relatively high frequency means The analysis also establishes that the pattern of groupings

a theoretical model of OBB can be used as a proxy for industrial essentially conforms to the structure of the WW framework.

sales personnel contextual knowledge. Furthermore, it is pos-As WW suggested, these forces are conceptually distinct while

sible to access this unique industrial contextual knowledge their impact on OBB in vivo is somewhat interactive. To date,

through the use of a theoretical model. The results of their those interrelationships were broadly specified but have never

assessments suggests that contextual knowledge unique to been empirically tested in toto. The results point to the

distinc-OBB exists and is accessible and could be made available to tion between forces external and internal to the buying

organi-train inexperienced sales personnel. zation. The environmental class did not interact with the other

Advertising agencies are marketers of business-to-business internal forces. Furthermore, a higher degree of interaction

services. Knowing the forces that affect the buying behavior was found among O and I classes to the virtual exclusion of

of potential of new clients and their relative occurrence should E and G.

225

Client–Agency Relationships J Busn Res

2000:49:213–228

firms they serve. The forces used in this study are from four client personnel play in agency selection endures from pro-gram to propro-gram for one client as well as across different broad categories: environmental, organizational, group, and

individual (psychological) found to affect organizations when clients. In particular, there are three roles likely to be carried out by up to three individuals. There is a person who controls they buy. Fewer than 10 of those items are concerned with

the more traditional target market factor programming. The the information client personnel receive from the agency. There is a main negotiator who acts as an opinion leader results indicate that most items (83%) were seen as active by

the respondents. By focusing on the top 20 most prevalent effecting the preferences of others involved. Finally, there is one person who initiated the selection process for any given forces in Table 1 one can conclude that for the four broad

classes, the grand order for frequency of occurrence is: I, O, campaign. The business marketing implication of these find-ings suggests that for an agency communication to be more G, and E. Several important detailed observations can be

made with implications for more effective new service business effective, it should take two steps. First, identify the individu-als involved and the particular role(s) they play with each acquisition.

campaign. Second, develop and target specific communication to these individuals based on these buying center roles

(Lich-The Importance of

tenthal, 1988; Bonoma 1982).

Individual Psychological Factors

The eight factors that are most prevalent in the business buying

The Role of Environmental Factors

behavior of clients belongs to the broad category of individual

Environmental forces represent those factors external to the (psychological) forces (Table 1). This suggests that agencies

client firm as a business buyer that affect their buying behavior should devote additional effort toward fostering a relationship

for agency services. Although these forces are of least influence predicated on trust and displayed expertise while reducing

overall (Table 1), client industry competitive intensity and client risk. This underscores the importance of recognizing

capital availability can not be ignored as an influence in agency and addressing the personal characteristics and needs of the

selection. individuals who are involved in the agency selection process

In summary, this study supports the notion that an OBB while pursuing traditional selling tactics based on program

framework can be applied to client–agency relationships. The and campaign characteristics.

client–agency relationship can be seen from a business-to-Clearly the high occurrence of these items highlights the

business service perspective. Many forces unique to business relatively high frequency of prevalence of the individual

cate-buying behavior were prevalent for the selection of agency gory items when compared to the other contextual knowledge

services according to sales personnel involved in cultivating categories. This finding concerning contextual knowledge

sug-new business. The findings suggest that agencies need to gests that organizational buying needs to be viewed from a

emphasize nonspecific campaign forces effecting agency selec-psychological and social selec-psychological perspective much like

tion. Moreover, the study also points to the importance of consumer behavior models.

identifying the effect of internal organizational forces and the roles buying center members play, side by side with campaign

The Importance of Client Internal

specific factors.

Organizational Structure and Goals

Doyle, Corstjens, and Michell (1980) suggest six client holding The authors appreciate the support and partial funding for this research

provided by the Institute for the Study of Business Markets at the Pennsylvania

strategies including vigilance to signals of vulnerability and

State University.

tactical adaptation to client organizational change. In this study, most prevalent organizational forces consist of a mix

between goals and objectives of the client’s campaign and the

References

internal structure of the client organization. In particular,Aaker, D. A., Batra, R. and Myers, J. G.:Advertising Management, 5th the departmental association of the people involved has a Ed., Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ. 1995.

significant influence. This suggests that an agency should iden- Anderson, E., Chu, W., and Weitz, B.: Industrial Purchasing: An tify the internal objectives of various client departments in- Empirical Exploration of the Buyclass Framework.Journal of

Mar-keting51 (January 1987): 71–86. volved as well as the client’s corporate marketing goals and

campaign objectives. This research lends further support to Bailey, K. D.:Typologies and Taxonomies: An Introduction to Classifica-tion Techniques, Sage University Papers, No. 102, Thousand Oaks, the notion that understanding organizational context is a

bet-CA. 1994. ter way of understanding organizational buying (Barclay,

Barclay, D. W.: Interdepartmental Conflict in Organizational Buying: 1991) and reducing interdepartmental conflict.

The Impact of Organizational Context.Journal of Marketing Re-search29 (May 1991): 45–59.

Roles of Client Personnel in Agency Selection

Beard, F.: Marketing Client Role Ambiguity As A Source of Dissatisfac-There is a group of individuals, on the client side, that is the tion in Client-Ad Agency Relationships.Journal of Advertising

Bonoma, T.: Major Sales: Who Really Does the Buying. Harvard Johnston, W., and Spekman, R. E.: Industrial Buyer Behavior: Where We Are and Where Need to Go, inResearch in Consumer Behavior Business Review(May–June 1982): 111–119.

vol. 2, J.N. Sheth, ed., JAI, Press, Greenwich, CT. 1987, pp. Buchanan, B., and Michell, P. C.: Using Structural Factors To Assess

83–111. The Risk of Failure in Agency-Client Relations.Journal of

Advertis-ing Research31 (August/September 1991): 68–75. Kohli, A., Determinants of Influence in Organizational Buying: A Contingency Approach. Journal of Marketing 53 (July 1989): Bunn, M.: Taxonomy of Buying Decision Approaches. Journal of

50–65. Marketing57 (January 1993a): 38–56.

Kotler, P.:Marketing Management: Analysis Planning and Control, 9th Bunn, M.: The Information Environment of Contemporary

Purchas-Ed., Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. 1997. ing Managers, presentation, Business to Business Marketing

Re-search Conference, ISBM(Penn State), (March 1993b), San Fran- Lichtenthal, J. D.: Group Decision Making in Organizational Buying:

cisco, CA. A Role Structure Approach, inAdvances in Business Marketing,

vol. 3, A. G. Woodside, ed., JAI Press, Greenwich, CT. 1988, pp. Campbell, D. T.: The Informant in Quantitative Research.American

119–157. Journal of Sociology60(4) (1955): 339–342.

Lilien, G. L., Kotler, P., and Moorthy, K. S.:Marketing Models, Prentice Cagley, J. W. and Roberts, C. R.: Criteria for Advertising Agency

Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. 1992. Selection: An Objective Appraisal.Journal of Advertising Research

24 (April/May 1984): 27–32. McQuiston, D. H.: Novelty, Complexity and Importance as Causal

Determinants of Industrial Buying Behavior.Journal of Marketing Cagley, J. W.: A Comparison of Advertising Agency Selection Factors:

53 (April 1989): 66–79. Advertiser and Agency Perceptions.Journal of Advertising Research

26 (June/July 1986): 39–44. Michell, P., and Sanders, N. H.: Loyalty in Agency-Client Relations:

The Impact of the Organizational Context.Journal of Advertising Choffray, J. M., and Lilien, G. L.: Assessing Response to Industrial

Research35 (March/April 1995): 9–22. Marketing Strategy.Journal of Marketing4 (July 1977): 20–31.

Michell, P.: The Influence of Organizational Compatibility on Ac-Cook, E. M.: Advertising in a Service Economy.Journal of Advertising

count Switching.Journal of Advertising Research28 (December/ Research29 (October/November 1989): 7–8.

January 1988): 33–38. Doyle, P., Corstjens, M., and Michell, P.: Signals of Vulnerability in

Agency-Client Relations.Journal of Marketing44 (October 1980): Michell, P.: Accord and Discord in Agency-Client Perceptions of

18–23. Creativity.Journal of Advertising Research24 (April/May 1984):

9–24. Ducoffe, R. H., and Smith, S. J.: Mergers and Acquisitions and the

Structure of the Advertising Agency Industry.Journal of Current Michell, P.: Agency-Client Trends: Polarization versus Fragmenta-Issues and Research in Advertising26 (Spring 1994): 15–27. tion.Journal of Advertising Research24 (April/May 1984): 41–52. Hambrick, D. C.: Taxonomic Approaches to Studying Strategy: Some Michell, P., Cataquet, H., and Hague, S.: Establishing the Causes Conceptual and Methodological Issues.Journal of Management10 of Disaffection in Agency-Client Relations.Journal of Advertising

(Spring 1984): 27–41. Research32 (March/April 1992): 41–48.

Henke, L. L.: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Ad Agency-Client Rela- Moncrief, W. C.: Selling Activity and Sales Position Taxonomies for tionship: Predictors of An Agency Switch.Journal of Advertising Industrial Sales Forces.Journal of Marketing Research23 (August Research35 (March/April 1995): 24–30. 1986): 261–270.

Hotz, M. R., Ryans, J. K. Jr., and Shanklin, W. L.: Agency/Client Moriarty, R. T., and Bateson, J. E.: Exploring Complex Decision Relationships As Seen by Influentials on Both Sides.Journal of Making Units: A New Approach.Journal of Marketing Research Advertising11 (Spring 1982): 37–45. 19 (May 1982): 182–191.

Hunt, S. D.:Marketing Theory: The Philosophy of Marketing Science, Moss, C.: Industrial Salesmen as a Source of Marketing Intelligence.

R.D. Irwin, Inc., Homewood, IL. 1983. European Journal of Marketing13 (March 1979): 94–102.

Hutt, M. D., and Speh, T. W.:Business Marketing Management, 6th Murphy, P., and Maynard, M. L.: Using Judgement Profiles to Com-Ed., Dryden Press, Hinsdale, IL. 1998. pare Advertising Agencies’ and Clients’ Campaign Values.Journal Johnson, J. L., and Lacniak, R. N.: Antecedents of Dissatisfaction in of Advertising Research36 (March/April 1996): 19–27.

Advertising Agency Relationships: A Model of Decision Making Robinson, P. J., Faris, C. W. and Wind, Y.:Industrial Buying and and Communication Patterns.Journal of Current Issues and Re- Creative Marketing, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA. 1967. search in Advertising14 (Spring 1992): 1–8.

Russell, J. T., and Lane, W. R.:Kleppner’s Advertising Procedure, 13th Johnston, W. J.: Industrial Buying Behavior: A State of the Art Review, Ed., Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. 1996.

inAnnual Review of Marketing, K. Roering, ed., American

Market-Sheth, J. N.: A Model of Industrial Buying Behavior.Journal of Market-ing Association, Chicago, IL. 1981, pp. 75–85.

ing37 (October 1973): 50–56. Johnston, W. J., and Lewin, J. E.: A Review and Integration of

Silk, A. J., and Kalwani, M. U.: Measuring Influence in Organizational Research on Organizational Buying Behavior.Marketing Science

Purchase Decisions.Journal of Marketing Research14 (May 1982): Institute(July 1994): 94–111.

165–181. Johnston, W. J., and Lewin, J. E.: Filling Some Holes in Organizational

Stewart, D. W.: The Application and Misapplication of Factor Analy-Buying Research, presentation, Business-to-Business Marketing

sis in Marketing Research.Journal of Marketing Research28 (No-Research Conference, ISBM (Penn State), San Francisco, March

vember 1981): 51–62. 1993.

Sujan, H., Sujan, M. and Bettman, J. R.: Knowledge Structure Differ-Johnston, W., and Spekman, R. E.: Special Section on Industrial

ences Between More Effective and Less Effective Salespeople. Buying Behavior: Introduction. Journal of Business Research 10

227

Client–Agency Relationships J Busn Res

2000:49:213–228

Tauber, E. M.: Advertising in a Service Economy.Journal of Advertising tions of Marketing Series, American Marketing Association, Chi-cago, IL. 1972b.

Research6 (April/May 1986): 3.

The Hunt for Clients Intensifies,The New York Times, August 3, Weitz, B. A.: Relationship Between Salesperson Performance and Understanding of Customer Decision Making.Journal of Marketing 1990.

Research15 (November 1978): 501–516. Walker, O. C. Jr., Churchill, G. A. Jr., and Ford, N. M.: Where Do

We Go From Here? Selected Conceptual and Empirical Issues Weitz, B. A.: Effectiveness in Sales Interactions: A Contingency Framework.Journal of Marketing45 (January 1981): 85–103. Concerning the Motivation and Performance of the Industrial

Sales Force, inCritical Issues in Sales Management: State of the Art Weitz, B. A., Sujan, H., and Sujan, M.: Knowledge, Motivation and and Future Research Needs, G. Albaum and G.A. Churchill, Jr., Adaptive Behavior: A Framework for Improving Selling Effective-eds., University of Oregon, Eugene, OR. 1979. ness.Journal of Marketing50 (October 1986): 174–191. Wackman, D. B., Salmon, C. T., and Salmon, C. C.: Developing Wilson, D. T., Lichtenthal, J. D., and Rethans, A. J.: Grounded Theory

An Advertising Agency-Client Relationship.Journal of Advertising in Organizational Buying Behavior: Back to the Past, inConsumer Research26 (December 1987/January 1988): 21–28. Psychology—Division 23 Proceedings, J. G. Saegert, ed., American Psychological Association, Washington, DC. 1986, pp. 13–16. Webster, C.: Industrial Buyer’s Level of Involvement with Services,

inMarketing Theory and Application, Lichtenthal, J. D., Spekman, Wind, Y., and Thomas, R. J.: Conceptual and Methodological Issues R. E., and Wilson, D. T., eds. AMA Proceedings Winter, Chicago, in Organizational Buying Behaviour.European Journal of Marketing

IL. 1990, pp. 69–74. 14 (May/June 1980): 239–263.

Webster, F. E., and Wind, Y.: A General Model for Understanding Zeithaml, V. A., Varadarajan, P., and Zeithaml, C. P.: The Contin-Organizational Buying Behavior.Journal of Marketing 36 (April gency Approach: Its Foundation and Relevance to Theory Building

1972a): 12–19. and Research in Marketing. European Journal of Marketing 22