Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

The Eye Diagram: A New Perspective on the

Project Life Cycle

Bin Jiang & Daniel R. Heiser

To cite this article: Bin Jiang & Daniel R. Heiser (2004) The Eye Diagram: A New Perspective on the Project Life Cycle, Journal of Education for Business, 80:1, 10-16, DOI: 10.3200/ JOEB.80.1.10-16

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.1.10-16

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 167

View related articles

anaging projects involves manag-ing change. Every project has a scope—the work that the project man-ager and team must complete to assure the customer that the deliverables meet the acceptance criteria agreed upon at the onset of the project. Successful proj-ect management, deployed around the project scope, is complex and difficult. Project managers must pay attention simultaneously to a wide variety of human, financial, and technical factors. Often, they are responsible for project outcomes without being given sufficient authority, money, or manpower. Not sur-prisingly, the project manager’s job is characterized by role overload, frenetic activity, and superficiality (Slevin & Pinto, 1987). In this article, we intro-duce an extension to the conceptual framework of the project life cycle to enhance the project manager’s under-standing of the dynamic and complex job of managing projects.

The concept of a project life cycle is well developed in project management literature. By their very nature, projects exist for a limited duration of time— they are born from an idea, developed into a finished product or service, and then terminated (Kloppenborg & Pet-rick, 1999). Organization personnel who manage projects routinely divide each one into several phases to provide better control and appropriate links to the

ongoing operations of the performing organization. The project life cycle pro-vides a useful framework for the project manager to (a) identify critical issues and probable sources of major conflict and (b) prioritize them over the process of the project implementation. We also readily acknowledge that in different life-cycle phases, the project will have different management requirements (Gray & Larson, 2003). As a project moves through its life cycle, the project manager and senior management should continually refocus their attention, ener-gy, and resources on the special

manage-ment requiremanage-ments of the relevant phase of the project.

In this article, we describe a new tool—the “eye diagram”—for enhanc-ing a project manager’s understandenhanc-ing of how his or her managerial perspec-tive should change as a function of the project life cycle. As the project life cycle transitions from one project phase to the next, the eye diagram also adjusts and resets its focus on a new perspective on the role of the project manager. The eye diagram provides a practical, intu-itive tool for project managers to cope with today’s increasingly complex and dynamic project environment.

A New Perspective on Project Management

No project exists in a vacuum; it is subject to an array of influences includ-ing its team’s perceptions and emotions, its organization’s control procedures, and economic and industrial interven-tion. To cope effectively, the project manager must have sophisticated knowl-edge of psychological, sociopolitical, institutional, legal, economic, and tech-nical influences. Therefore, a successful project manager should be highly skilled, perceptive, and display excellent boundary communication skills at the “institutional management level” (Mor-ris, 1982) or the “strategic apex”

The Eye Diagram:

A New Perspective on

the Project Life Cycle

BIN JIANG DANIEL R. HEISER

DePaul University Chicago, Illinois

M

ABSTRACT. The project life cycle, a well-established concept in project management literature and education, is used to highlight the dynamic requirements placed on a typical proj-ect manager. As a projproj-ect moves through the selection, planning, execu-tion, and termination phases, the proj-ect manager and team are faced with different, vying areas of concern— including the immediate task priorities, the probable sources of conflict, and the relevant critical factors for project suc-cess. Unfortunately, traditional repre-sentations of the project life cycle emphasize accounting-oriented aspects of the life cycle that are less interesting, such as percent complete and level of effort. In this article, the authors intro-duce a new framework, the eye dia-gram, that illustrates the more substan-tive aspects of the life cycle concept in an intuitive and accessible format.

(Mintzberg, 1979). A project manager must know how to plan effectively and act efficiently (Slevin & Pinto, 1987) to coordinate project strategy and tactics coherently in the relevant competitive environment. In short, the project man-ager must manage an area larger than the territory bounded by the scope of the project.

The project manager faces a complex task requiring attention to many vari-ables. This inherent complexity arises from the diverse and novel nature of projects. The more specific a manager can be regarding the definition and monitoring of the pertinent variables, the greater the likelihood of a successful project outcome. It generally is useful to use a multiple-factor model, because it can help a project manager first under-stand the variety of factors affecting project success, then to be aware of their relative importance across project implementation stages.

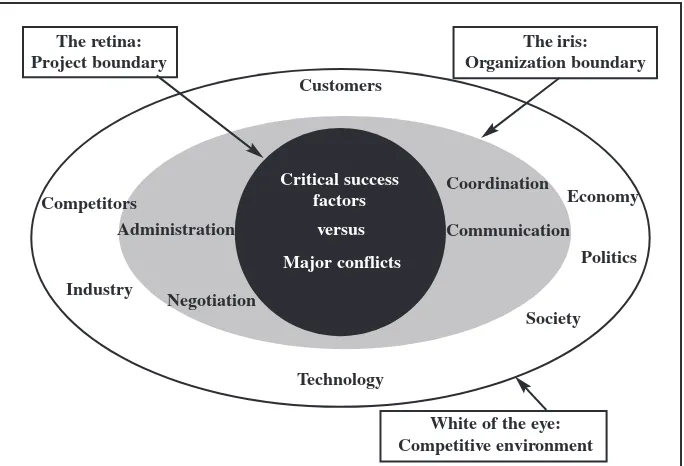

In Figure 1, the eye diagram, we illustrate the multifactor project envi-ronment, which we use to define and monitor the standard variables pertinent in project management. The black “ret-ina” of the eye represents the scope of the project. Project managers should have the skill set and ability to define the project scope, set up the project team, identify and address project risks

and constraints, and estimate and moni-tor time while staying within the bud-get. In recent years, researchers have focused on identifying the factors most critical to project success and failure (Thamhain & Wilemon, 1975).

The gray “iris” surrounding the proj-ect scope represents the parent organi-zation supporting the project. Although it would be unusual for a project man-ager to control the interface between the project and the parent organization (this arrangement normally is a matter of company policy decided by senior man-agement), the nature of the interface has a major impact on the project. Accord-ing to the characteristics of this inter-face, the project manager will negotiate with functional departments, be subject to human resource directives, and bar-gain for and coordinate the organiza-tion’s scarce resources. The rapid growth in the use of projects to imple-ment strategic change, collapse product development cycles, and improve ongo-ing operations has made the traditional interface between projects and their par-ent organizations inadequate in many cases (Mantel, Meredith, Shafer, & Sut-ton, 2001).

The surrounding “white of the eye” represents the external environment in which the project and the organization are located. This environment includes

the established and latest state-of-the-art technology relevant to the project; its customers and competitors; and its geo-graphical, climatic, social, economic, and political settings—virtually every-thing that can affect a project’s success. These factors can influence the plan-ning, organizing, staffing, and directing that constitute the project manager’s main responsibilities. Therefore, for the project managers to be consistently suc-cessful, they must take into account the effects of the wider environment.

Changing Focus During the Project Life Cycle

Successful project leaders are aware of the links between completion of the project life-cycle phase and the chang-ing internal and external variables affecting project management. For the present study, we employed a four-phase life-cycle model including project selection, planning, execution, and ter-mination, as suggested by Hormozi, McMinn, and Nzeogwu (2000). As a project moves through each phase, the project manager and senior management should continually monitor the project’s critical success factors to ensure it is still viable. As a result, the managers will need a variety of leadership and man-agement skills to guide the project through each phase of the project life cycle (Verma, 1996). The life cycle must be understood and internalized by the project manager because the necessary managerial foci subtly shift at different phases (Kaplan, 1986).

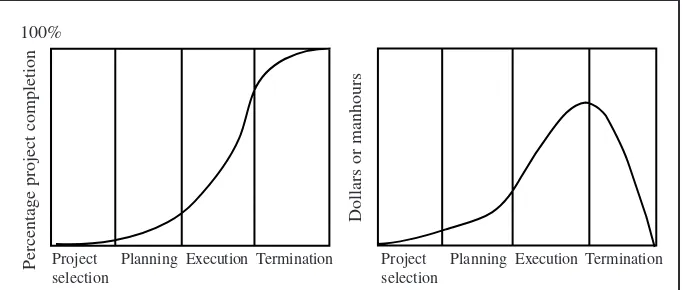

When we read the “project life cycle” section in current project management textbooks and handbooks, we typically find the two illustrations shown in Fig-ure 2 (Meredith & Mantel, 2003). These frameworks remain useful because they help to define the level of effort needed to perform the tasks associated with each phase. During the early phases, requirements are minimal; however, they rapidly increase during late plan-ning and execution stages and diminish during project termination (Pinto & Prescott, 1990).

However, although the traditional illustrations show that project manage-ment is affected by the elapsing life cycle, they are so simple that they lose The retina:

Project boundary

The iris: Organization boundary

White of the eye: Competitive environment

FIGURE 1. The eye diagram of project management.

much of the underlying power of the life-cycle concept—and even may mis-lead inexperienced project managers. For example, according to the graphs in Figure 2, one easily could believe that a project’s life cycle is used for measuring project completion as a function of either time or resources. However, the real purpose of a project life cycle is to provide project man-agers with an a priori strategic and tac-tical tool rather than a post hoc mea-surement scale. In this article, we point out the advantage of using the eye dia-gram for tracking different phases of the project life cycle. With the eye dia-gram, we find that each new perspec-tive supports the underlying concept and requirements of the individual life-cycle phases better than do traditional illustrations.

Phase 1: Project Selection—Outward-Looking Eye Diagram

Project selection, the initial phase, refers to the time frame during which a strategic need is recognized by top man-agement. It starts with identifying the needs and desires of the user of the proj-ect deliverables—the customer. The company’s major business objectives and strategies need to be identified and understood so that project goals can be accurately associated with them. In this phase, top management needs to be out-ward looking to serve as project cham-pion, publicist, and persuader, harness-ing the approval and commitment of investors, regulatory bodies, govern-ment, interest groups, and even the gen-eral public. This phase demands flexi-bility, awareness, entrepreneurial skill, and political insight (Thamhain & Wile-mon, 1975). The eye diagram relevant to the selection phase emphasizes the outward-looking, environmental scan-ning requirements of this initial phase of the life cycle (see Figure 3).

Phase 2: Planning—Iterative Eye Diagram

During the planning phase, a more formalized set of project plans (e.g., schedule and budget) are established for accomplishing the intended project scope. Two main types of activities are

accomplished: dealing with iterative planning and initiating the formation of the project team. The project manager needs to stimulate the design profes-sionals, liaise and negotiate with func-tional departments, and deal with any regulatory and other oversight bodies. The project manager and newly assigned team members meet to plan jointly at a macro level of detail the major activities that must be accom-plished. Then project team members, individually or in smaller groups, often will flesh out the details of necessary work in their respective areas (Kloppen-borg & Petrick, 1999). Then the team “rolls up” these detailed activity plans to identify schedule, cost, and resource plans in detail. This phase requires the project manager to have empathy when setting the design objectives and patience for coping with organizational bureaucracies (Sidwell, 1990). In Figure 4, we illustrate this planning phase’s eye diagram and emphasize the iterative nature of activities required to refine project plans. As illustrated, the activity

at this stage occurs outside the bound-aries of the project scope (the work to be performed for the end customer) and consists primarily of administrative tasks inside the sponsoring organization.

Phase 3: Execution—Sequential Eye Diagram

The third phase in the life cycle is pro-ject execution. During this phase, the actual work of the project is performed (Pinto & Prescott, 1990). The main activities of this phase include securing the necessary resources to perform each project task, executing the activities identified in the project plan in the planned sequence, monitoring and reporting on progress, and replanning and adapting to fluid conditions as need-ed. Progress needs to be monitored and reported on a regular basis to track progress. This is generally the longest phase of the project both in terms of dura-tion and effort (Kloppenborg & Petrick, 1999). The project manager must cope with a large, diverse, action-oriented

Percentage project completion

100%

Dollars or manhours

Project selection

Planning Execution Termination Project selection

Planning Execution Termination

FIGURE 2. Traditional project life-cycle illustrations.

FIGURE 3. Project selection phase: Outward-looking eye diagram.

FIGURE 4. Planning phase: Iterative eye diagram.

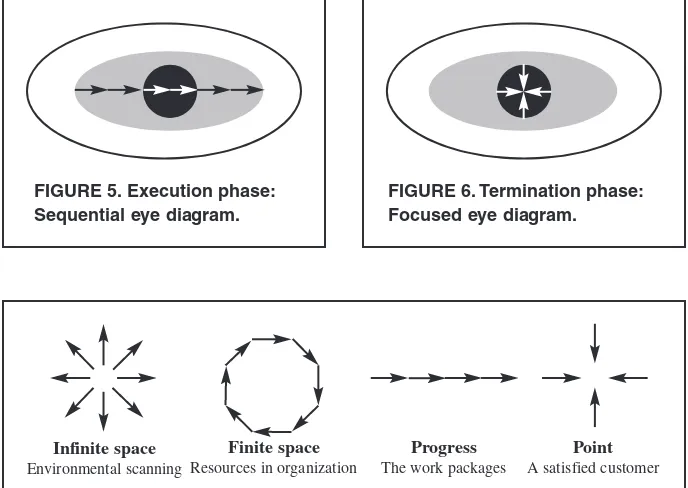

team and often must operate under extreme time and cost pressures. The pro-ject manager is involved in simultane-ously monitoring and controlling the project and may need to become the pri-mary driver of the project (Sidwell, 1990). The execution perspective of the eye diagram emphasizes the sequential nature of the project activity (see Figure 5). Although the majority of the work occurs within the black retina of the eye diagram (the project scope), the inter-face with the sponsoring organization (e.g., coordinating with functional departments and reporting progress) remains an important element of the pro-ject manager’s concern.

Phase 4: Termination—Focus Eye Diagram

The last phase in the project life cycle is the termination phase. During the transition from execution to termina-tion, the project manager leads the proj-ect team in assisting the end users in operating the new product or service. Once the project scope has been accom-plished, the resources assigned to the project must be released. Personnel from the project team are reassigned to other duties, and ownership of the proj-ect output is transferred to its intended users. This phase is a valuable opportu-nity for evaluating and improving the organization’s project management capability and capturing “lessons learned” for the organization’s knowl-edge management system. The intro-spective nature of the termination per-spective is shown by the inward flow of the eye diagram in Figure 6.

When we place the four eye diagram perspectives in order, an interesting pro-gressive pathway of changing manager-ial foci emerges (see Figure 7). Begin-ning with all potential variables that influence a project and ending with an exclusive focus on a satisfied customer, the changing perspectives show how a project manager must change his or her focus from the initial macro level to the final micro point.

Additional Relationships

Thus far, we have demonstrated that the changing perspective of the eye

dia-gram provides improved guidance for managerial focus when compared with the traditional project life-cycle illustra-tions in Figure 2. However, the useful-ness of the tool can be extended into additional areas of interest that typically are prevalent during each phase of the project management life cycle. The dynamics of the project implementation process have been examined from a variety of perspectives, but researchers often concentrate on two areas: critical success factors and dealing with con-flict. The eye diagram also can be lever-aged to represent characteristics rele-vant to both areas of concern.

Critical Success Factors

It is well recognized in project man-agement research that the project imple-mentation process can be facilitated greatly if a variety of critical success factors are addressed (Boynton & Zmuc, 1984; Shank, Boynton & Zmuc, 1985). One of the typical studies on this topic was reported by Slevin and Pinto (1987). After interviewing more than 400 project managers, Slevin and Pinto identified the 10 most common critical factors relevant to project success:

1.Project mission. Initial clarity of goals and general directions.

2.Top management support. Willing-ness of top management to provide the necessary resources and authority/ power for project success.

3.Project schedule and plans. A detailed specification of the individual action steps required for project imple-mentation.

4.Client consultation. Communica-tion, consultaCommunica-tion, and active listening to all concerned parties and potential users of the project.

5.Personnel. Recruitment, selection, and training of the necessary personnel for the project team.

6.Technical tasks. Availability of the required technology and expertise for accomplishing the specific technical action steps.

7.Client acceptance. The act of “sell-ing” the final project to its ultimate intended users.

8.Monitoring and feedback. Timely provision of comprehensive control information at each stage in the imple-mentation process.

9.Communication. The provision of an appropriate network and necessary data to all key actors in the project implementation.

10.Troubleshooting. Ability to handle unexpected crises and deviations from the plan.

FIGURE 5. Execution phase: Sequential eye diagram.

FIGURE 7. Changing focus during the project life cycle.

Infinite space

Environmental scanning

Finite space

Resources in organization

Progress

The work packages

Point

A satisfied customer

FIGURE 6. Termination phase: Focused eye diagram.

Among the 10 factors, the first three (mission, top management support, and project schedule and plans) are strate-gic; the remainder are tactical. Slevin and Pinto (1987) also studied the shift-ing balance between strategic and tac-tical issues over the project’s life cycle (see Figure 8). During the two early phases, selection and planning, strate-gy is significantly more important to project success than tactics. As the proj ect moves toward the final stage, strat-egy and tactics achieve almost equal importance. The initial strategies and goals continue to “drive” or shape tac-tics throughout the project (Slevin & Pinto).

This view coincides with the eye dia-gram’s changing perspectives. The focus shifts from broad scale (strategy) to small scale (tactics), but the funda-mental goal—to satisfy the customer— is always driving the project manager’s attention and activity.

Conflict and Projects

Managing conflict is a fundamental part of overseeing complex projects. To anticipate and quickly address conflict, it not only is essential for project man-agers to be cognizant of the potential sources of conflict; they also must know when in the life cycle such conflicts are most likely to occur. Such knowledge can help the project manager avoid unnecessary delays in dealing with the detrimental aspects of conflict and max-imize any opportunities presented to capture the beneficial aspects of conflict (Thamhain & Wilemon, 1975).

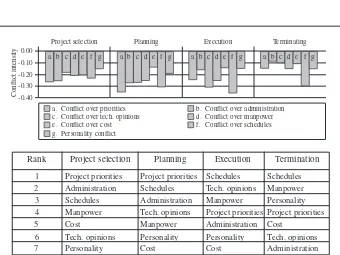

The causes of project conflicts are varied. After investigating more than 100 projects, Thamhain and Wilemon (1975) identified several different sources of conflict and noted that the sources seemed to differ when a project is in different phases of its life cycle (see Figure 9). Despite the passage of several decades, Thamhain and Wile-mon’s findings are considered relevant to the modern project-management environment (Mantel et al., 2001).

Again, many of the results of Thamhain and Wilemon’s (1975) research align with the multiple per-spectives of the eye diagram. As strate-gic level conflicts (e.g., conflict over

project priorities and administrative interfaces) gradually fade, high-ranking conflicts shift to microlevel issues (e.g., technical opinion, personality, man-power). Although other sources of con-flict (such as those related to the sched-ule) always rank high, the eye diagram helps to filter the probable areas of con-cern into a smaller, more digestible subset.

The project selection phase. In this phase, the eye diagram suggests that the project manager and top management should focus on environmental scan-ning—assessing both the opportunities and threats affecting the project.

Thamhain and Wilemon (1975) argued that if project managers are aware of the importance of each potential con-flict source by project life cycle, then they can employ more effective conflict minimization and resolution strategies. Therefore, during the selection phase, the project manager should focus on macrolevel issues, such as project mis-sion, top management support, project schedule, project priorities, and admin-istrative procedures.

The planning phase.Once the selection is complete, the eye diagram refocuses from an outward scanning mode to an intra-organizational mode. This means

0.7

Importance (beta weights)

Strategy

Tactics

Project selection Planning Execution Termination

Phases

FIGURE 8. Changes in strategy and tactics across the project life cycle.

a. Conflict over priorities b. Conflict over administration

c. Conflict over tech. opinions d. Conflict over manpower

e. Conflict over cost f. Conflict over schedules

g. Personality conflict 0.00

Project selection Planning Execution Terminating

a b c d e f g a b c d e f g a b c d e f g a b c d e f g

Rank Project selection Planning Execution Termination

1 Project priorities Project priorities Schedules Schedules 2 Administration Schedules Tech. opinions Manpower 3 Schedules Administration Manpower Personality 4 Manpower Tech. opinions Project priorities Project priorities 5 Cost Manpower Administration Cost

6 Tech. opinions Personality Personality Tech. opinions 7 Personality Cost Cost Administration

FIGURE 9. Ranks of conflict intensities in different project life-cycle phases.

that the project manager needs to plan carefully how to make full use of the organization’s resources. The project manager still needs to think at a strate-gic level to negotiate with functional departments for resources and capacity to support a practical master plan. While keeping the project mission in mind, the project manager should place attention on project priorities, sched-ules, administrative procedures, and communication.

The execution phase. During project execution, the relevant critical success factors tend to emphasize the impor-tance of focusing on the “how” instead of the “what” (Slevin & Pinto, 1987). Factors such as personnel, communica-tion, and monitoring are concerned with better management of specific action steps in the project implementation process. Throughout this phase, the actual progress of the project, in terms of cost, schedule, and performance, is

measured against the planned goals. The eye diagram shifts focus to the sequential activities necessary to drive project progress. High priority factors should be scheduling, monitoring and feedback, technical tasks, and trou-bleshooting.

The termination phase.By the time the project nears completion, many project team members are tired and behind in other work (Kloppenborg & Petrick, 1999). Thus, the eye diagram suggests that the project manager and team should focus their limited energies on the funda-mental goal—satisfying the customer. As a result, the critical factors should be schedule completion, client acceptance, and personality (i.e., team motivation and selling the solution to the client).

In Figure 10, we provide a summary of the relations among the eye diagram, critical success factors, and sources of project conflict across the project life-cycle phases.

Conclusions

Compared with the traditional “per-cent completion” or “level of effort” pro-ject life-cycle models, the eye diagram provides project managers with a more complete and intuitive framework to sup-port project management. It guides the project manager to shift his or her thoughts from the broad competitive environment to the internal organization-al politicorganization-al framework, to the work asso-ciated with the project scope, and, final-ly, to an ultimate spotlight on customer satisfaction. The disciplined use of an eye diagram model, associated with crit-ical success factors and conflict predic-tion methods, will help project managers know how and where to focus their ener-gies and resources during different proj-ect life-cycle phases. Thus, the eye dia-gram provides a clear and intuitive guideline to assist project managers as they cope with today’s increasingly com-plex project-management environment.

Life-cycle Eye diagram Critical success Probable sources

phases perspective factors of conflict

Selection Project mission Project priorities

Top management support Administration procedures

Project schedule Schedule

Planning Project mission Project priorities

Top management support Schedule

Project schedule Administration procedures

Communication

Execution Project schedule Schedule

Monitoring and feedback Technology opinions

Troubleshooting Manpower

Technical tasks Personnel Client consultation

Termination Monitoring and feedback Schedule

Client acceptance Manpower

Communication Personality

Client consultation Personnel

FIGURE 10. Eye diagram, critical success factors, and project conflicts.

REFERENCES

Boynton, A., & Zmuc, R. W. (1984, Summer). An assessment of critical success factors. Sloan Management Review,17–27.

Gray, C. F., & Larson, E. W. (2003). Project man-agement: The managerial process (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hormozi, A. M., McMinn, R. D., & Nzeogwu, O. (2000, Winter). The project life cycle: The ter-mination phase. SAM Advanced Management Journal,45.

Kaplan, R. S. (1986, March/April). Must CIM be justified by faith alone? Harvard Business Review,87–93.

Kloppenborg, T. J., & Petrick, J. A. (1999, June). Leadership in project life cycle and team

char-acter development. Project Management Jour-nal,8–13.

Mantel, S. J., Meredith, J. R., Shafer, S. M., & Sutton, M. M. (2001). Project management in practice. New York: Wiley.

Meredith, J. R., & Mantel, S. J. (2003). Project management: A managerial approach. New York: Wiley.

Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organi-zations. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Morris, P. W. (1982). Project organizations— Structures for managing change. In A. J. Kelly (Ed.),New dimensions of project management

(pp. 155–180). Garfield, WA: Lexington Books. Pinto, J. K., & Prescott, J. E. (1990). Planning and

tactical factors in the project implementation process. Journal of Management Studies, 27(3),

305–323.

Shank, M., Boynton, A., & Zmuc, R. W. (1985, June). Critical success factor analysis as a methodology for MIS planning. MIS Quarterly, 121–129.

Sidwell, A. C. (1990, August). Project manage-ment: Dynamics and performance. Construc-tion Management and Economics, 160. Slevin, D. P., & Pinto, J. K. (1987, Fall).

Balanc-ing strategy and tactics in project implementa-tion. Sloan Management Review, 33–41. Thamhain, H. J., & Wilemon, D. L. (1975,

Spring). Conflict management in project life cycles. MIT Sloan Management Review, 31–49. Verma, V. K. (1996). Human resource skills for the project manager. Upper Darby, PA: Project Management Institute.