CO M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S

F I N A L R E P O R T

Annelies Heijmans

Independent Consultant & Researcher (PhD)

Saut Sagala

Assistant Professor | Institute of Technology Bandung

February 2013

Acknowledgement

In its attempts to better understand what has been achieved in community resilience and

community based disaster risk management in Indonesia, the Australia-Indonesia Facility for Disaster Reduction (AIFDR) supported a study into community resilience and self-reliance in November-December 2012. While the study does not capture all of the stories and best practice in this field, due to the limited research time, we were extremely lucky to work with two dedicated and professional consultants, Annelies Heijmans and Saut Sagala, who planned and crafted the research, undertook field investigations, developed CBDRM models and completed the analysis that we are presenting to you now.

AIFDR would like to thank all of the communities visited for contributing their time, and for sharing their stories and experiences with us. We are also grateful to our interviewees from the National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB), particularly Ir. Bernardus Wisnu Widjaja M.Sc and Drs.

Muhtaruddin, BNPB consultant Chasan Ascholani, M.Si, Togu Pardede from Bappenas, Wayne Ulrich and Robert Sulistyo from IFRC, Irina Rafliana from LIPI, Lukman Hakim from Oxfam in Indonesia, Ari Nugroho, Dame Manalu and Dian Lestariningsih from Karina, Amin Magatani from Plan International, Abby Mamesah from World Vision, Prih Harjadi from BMKG, Avianto Muhtadi from Nahdlatul Utama, and academics Jonatan Lassa and Eko Teguh Paripurno.

Our utmost appreciation also goes to our interviewees in East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) for their generous and frank contributions and insights, including Ellen and Poli from Caritas Maumere, Eko from Wetlands International, Sylavanus Tibo from BPBD Sikka, Anton from LPTP, Yayo and Ruslan from BPBD Ende, and Roni and Vincent from the Flores Institute for Resource Development (FIRD). From West Sumatra we particularly thank Simon Matakupan from Mercy Corps, Turmizi from SurfAid International, Patra Rina Dewi from Kogami, Jefriyanto, Rumainur and Richard from the West Sumatra BPBD, Zainir Koto and Syafrimen from the Padang Pariaman BPBD, Nurhayati and Fatmiyeti from Limbubu NGO, Budhi Erwanto and Hermansyah from the Kota Padang BPBD.

In West Aceh, we particularly like to thank Pak Aria and his colleagues from IBU-Foundation-Meulaboh for their contributions and for arranging the interviews with village heads and CBDRM-teams in Desa Langung, Desa Gampung Pasir, Desa Kautumbang, and with FORMASIBAB. We highly appreciated the insights shared by H. Teuku Ahmed Dadek, head of BPBD West Aceh, and for explaining the achievements in West Aceh since the tsunami in 2004.

In East Java there are many people to whom we are grateful. First of all to Pak Darmawan, head BPBD East Java Province and Pak Sugeng, Director Preparedness and Mitigation BPBD East Java, to Buju Gunjoro, secretary of BPBD Blitar and Kaltian, Emergeny and Logistics BPBD Blitar, Bapak Wiyono, head BPBD Banyuwangi, Pak Suhardi and Ibu Nadif Ulfia from BPBD Bojonegoro, to Akhmad Junaida, Mas Polo, DC and Mita from Yayasan Indonesian Cerdas, to Arif Santoso of Jawa Pos, to Mas Oni from Walhi-Surabaya, Djoni Irianto from PMI-East Java, Abdul Habdi Rashid from Jangkar Kelud, Gendon from Kappala, to the preparedness teams from desa Besowo, Desa Satak, Desa Widang and Desa Solo all in Blitar, to PMI staff in Banyuwangi, CBAT-PMI in desa Sumberagung, Pesanggaran sub-district, and to Jainal Anis from FPBI Banyuwangi.

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 3

We further like to thank AIFDR’s provincial DRM consultants, Didik Mulyono (East Java) and Wawan Budianto (West Sumatra), for their insightful contributions to discussions and analysis. Also the invaluable inputs and feedback on interim reports from Ben O’Sullivan, Jeong Park, Piter Edward, and Allan Bell of DFAT’s Disaster Response Unit were highly appreciated.

Special thanks is due to the staff of AIFDR especially to Rina Amalia, Trevor Dhu, Tini Astuti, Widya Setiabudi and Elia Surya for managing the field work logistics, for their teamwork during and after field visits, and for their continuing support to improve the quality of this study. We hope that the experiences, insights and ideas from this study will inspire others to contribute to Indonesia becoming safer and more resilient.

Please enjoy,

On behalf of AIFDR Team: Jason Brown

Training & Outreach Manager

Table of Contents

Acknowledgement 3

Executive Summary 6

1. Introduction 8

1.1 Overarching aim and specific objectives of the Community Self-Reliance Analysis 8

1.2 Definition of concepts 9

1.3 Research questions 11

1.4 Conceptual framework 12

1.5 Scope and methodology for the analysis 16

1.6 Structure of the report 17

2. Situational analysis of CBDRM in Indonesia – challenges, gaps and needs 19 2.1 The broader political and institutional context of Indonesia related to DRM 19

2.2 Local level DRM practices in Indonesia 20

2.3 Capacity of NGOs to work with government and to link communities with government 23

2.4 Challenges, gaps and needs 24

3. Overview of key findings and observations from the field visits 27 3.1 How is CBDRM defined and operationalized in practice? 27 3.2 How do the various actors view and interact in the

(CB)DRM spaces to realize their interests? 36

3.3 Effective strategies to achieve community resilience and building partnerships 41 3.3.1. CBDRM as empowering process towards institutional development 41 3.3.2 CBDRM as a project to establish disaster-preparedness teams linked

to CBO-network and BPBD 43

3.3.3 Project-oriented and school-based CBDRM approach 44 3.3.4 Inter-sectoral approach to CBDRM integrating disaster preparedness with livelihood concerns and institutional development - Partners for Resilience 45 3.3.5. CBDRM through faith-based organizations and networks 46

3.4 Conclusions 47

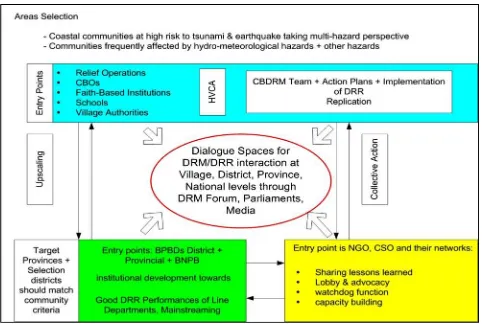

4. Developing a theory of change for achieving community resilience in Indonesia 49 4.1 A road map for achieving community resilience taking

various entry-points and pathways 52

4.2 Rationale for area selection 54

4.3 Rationale for the various entry points to communities 56 4.4 Entry-points at district and provincial level: BPBDs 57 4.5 Existing NGO-CSO networks at district, provincial and national level as entry-points 58

4.6. Constraints to the envisioned change 60

4.7 AIFDR’s role and added value in achieving this change 61 4.8 Other DRM actors’ roles in achieving this change 61

5. Evidence-based approaches to CBDRM 63

5.1 School-based CBDRM approach 63

5.2 NGO/CSO facilitates community disaster preparedness and linkage

building with CBOs and BPBD 64

5.3. Relief and livelihood recovery as entry-point for comprehensive

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 5

5.4 Inter-sectoral partnership approach to CBDRM contributing to institutional development 67 5.5 Key strategies for achieving community resilience 68

1. Effective CBDRM involves a change in mind-sets 69

2. Effective CBDRM seeks inclusiveness during the process 70 3. Effective CBDRM recognizes local people’s perspectives, priorities

and their knowledge to deal with adversity with a focus on livelihood resilience 71 4. Mobilization of social action and effective civil society led advocacy for DRM

is effective for making government accountable and a responsible actor in DRM 72 5. Effective CBDRM builds on different bodies of knowledge 72 6. Effective CBDRM is linked to, seeks cooperation with, and involves different actors,

including government departments towards establishing

formal GO-CSO DRR Coordination Bodies 74

7. Institutionalizing CBDRM in national development planning: further up-scaling 75 8. CBDRM approaches remain effective and relevant through

continuous real-time learning and systematizing knowledge 76 9. Effective CBDRM seeks creative and innovative funding and support strategies 77

References 79

List of abbreviations 84

Executive Summary

This Community Self-Reliance Analysis aims to provide a broad assessment of how different civil society organizations, international and local non-governmental organizations, government agencies, community networks, the private sector and media interact and engage in the disaster management spaces in Indonesia. The analysis is expected to produce evidence-based approaches to CBDRM that are effective and sustainable, and can be considered for AIFDR’s new DRM

programme.

This analysis conceives CBDRM in the broader political and institutional context of Indonesia and pro poses to use the notion of ‘community resilience’ instead of ‘community self-reliance’. Community resilience recognizes the continuous changing nature of disasters in the future, and communities’ abilities to effectively anticipate, respond and adapt to disasters and to transform interactions with government into functioning institutions and good DRM governance.

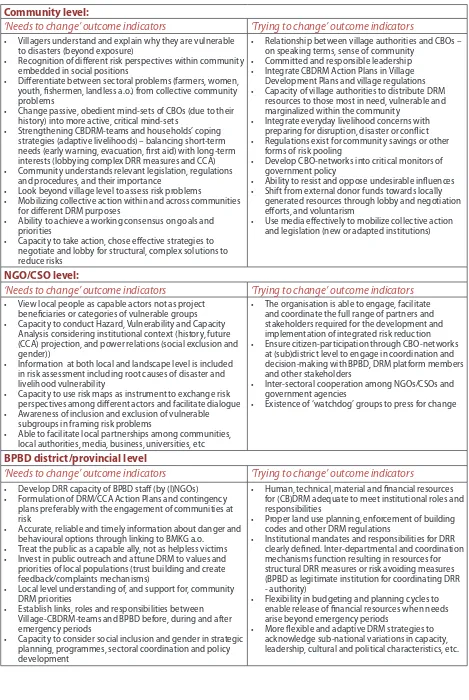

Based on CBDRM literature review, field visits to East Java, Nusa Tenggara Timur, West Aceh, and West Sumatra, and interviews with Jakarta-based organizations, we developed a theory of change for achieving community resilience. The analysis indicates that this may happen through:

n Changing mind-sets about how DRM actors interpret disasters, perceive other DRM actors

and practice CBDRM. Focus is on transformational learning and critical reflection instead of education.

n Change as a result of contradictions in society. We observed that many laws and regulations on DRM exist that favour community resilience, but that these are not implemented due to constraints within government and between government and vulnerable people. Efforts to make government policies congruent with practice will be target of the change agenda by improving both CSO organisational capacity and GoI organisational capacity through their critical interaction as opposed to viewing them as two parallel isolated tracks.

n A way to influence and change government performance in DRM is to mobilize social action through strong CSO/NGO networks which engage with government, private sector, knowledge centres at various levels.

n To achieve the three points above, creation of DRM dialogue spaces is required where the different DRM actors meet, share experiences, coordinate DRM efforts, negotiate and decide about DRM resource allocation. Different strategies are possible ranging from informal workshops towards lobby and advocacy in more formal DRM platforms or in district/provincial parliaments.

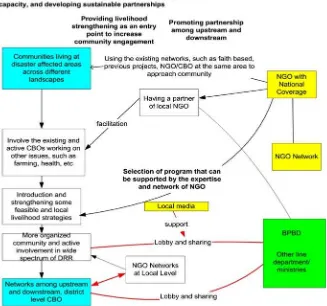

We see this change happening by fostering community resilience on one hand (bottom-up

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 7

Interactions are encouraged to take place at different localities and administrative levels where we want change to happen. Therefore we arrived at criteria for area selection and different entry-points pulled together in a road map. We recommend to select:

(1) Coastal communities at high risk for tsunami and earthquake taking a multi-hazard perspective (2) Communities frequently affected by hydro-meteorological hazards without excluding other

hazards

(3) Select communities cluster-wise affected by the same hazard-type taking a landscape approach.

Chapter 5 presents four evidence-based approaches to CBDRM that foster community resilience at the local level and have the potential to contribute to institutional development at district/ provincial levels. The four approaches are not exclusive and shouldn’t be perceived as blue-prints. They can be combined, blended or applied in a sequential manner depending on local settings, needs and abilities of the DRM actors involved. The four approaches are based on effective strategies that we observed in Indonesia during the conduct of this analysis and previous research and can be labelled as follows:

1. School-based CBDRM approach

2. NGO/CSO facilitates community disaster preparedness and linkage building with CBOs and BPBD

3. Relief and livelihood recovery as entry-point for comprehensive CBDRM addressing root causes of people’s vulnerability

4. Inter-sectoral partnership approach to CBDRM contributing to institutional development The second part of this chapter summarizes the nature of effective and sustainable CBDRM practices through nine key-strategies that should be considered in each of the four approaches to CBDRM mentioned above to achieve community resilience:

1. Effective CBDRM involves a change in mind-sets

2. Effective CBDRM seeks inclusiveness during the process

3. Effective CBDRM recognizes local people’s perspectives, priorities and their knowledge to deal with adversity with a focus on livelihood resilience

4. Mobilization of social action and civil society-led advocacy for DRM is effective for making government accountable and a responsible actor in DRM

5. Effective CBDRM builds on different bodies of knowledge

6. Effective CBDRM is linked to, seeks cooperation with, and involves different actors, including govern ment departments towards establishing GO-CSO coordination bodies

7. Institutionalizing CBDRM in national development planning

8. CBDRM approaches remain effective and relevant through continuous real-time learning and systematizing knowledge

Introduction

Dihilangkan dan diganti dengan: Community Self-Reliance Analysis is commissioned by the Australia-Indonesia Facility for Disaster Reduction (AIFDR). Community self-reliance refers to the ability of communities to effectively prepare for and mitigate disaster risks. This is assumed to be achieved through partnerships between district disaster management agencies (BPBDs) and CSOs to facilitate community knowledge and behavioural change”. This Community Self-Reliance Analysis aims to provide an in-depth analysis on approaches that foster community self-reliance. The analysis will provide a broad assessment of how different CSOs, NGOs, INGOs, government actors and community networks interact and engage in the disaster management space. The analysis is expected to

produce recommendations regarding approaches that the DRM program should trial.

1.1 Overarching aim and specific objectives of the Community

Self-Reliance Analysis

This Community Self-Reliance Analysis is being commissioned to provide an in-depth analysis on approaches that foster community self-reliance. The analysis will provide a broad assessment of how different CSOs, NGOs, INGOs, government actors and community networks interact and engage in the disaster management space. The analysis is expected to produce recommendations regarding approaches that the DRM program should consider for funding.

The recommended approaches and pre-requisites for building community self-reliance should be placed within the DRM strengthening Government of Indonesia’s preparedness to respond to disaters should go hand-in-hand with the strengthening of community self reliance.. These two tracks shouldn’t be regarded as separate approaches; the analysis will look beyond the binaries of bottom-up and top-down approaches to reduce risks, and attempt to understand how government, CSOs and communities interact and engage with each other in the various DRM spaces. The specific objectives of the analysis are three-fold as stated in the Terms of Reference:

Explore existing approaches for building linkages between government, CSOs and communities

These include approaches of the Indonesian Government like e.g. BNPB’s Resilient Villages Programme, and approaches of CSOs and their networks. Particularly the sustainability of approaches will be analysed, and how these approaches could be funded in the future and potentially replicated on a larger geographic scale across Indonesia. These approaches will be described in detail referring to how the approach can be implemented, key factors that may contribute to the success or failure of the approach, and the pros and cons of each approach.

Explore how CSOs implement CBDRM and how they interact in DRM spaces

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 9

Identify effective approaches and pre-requisites for building community-self reliance

This section will bring together the insights from the two sections above and makes sense of each actor’s role and responsibility in building self-reliant communities. Approaches and pre-requisites for building community self-reliance will recognize political barriers that might exist between relevant DRM actors and strategies to overcome these. The analysis will look for ‘institutional homes’ for DRM and building community self-reliance.

1.2 Definition of concepts

The Disaster Risk Concept Note (AusAid, 2012: 2) defines community self-reliance as the ability of com munities to effectively prepare for and mitigate disaster risks. This is assumed to be achieved through partnerships between district disaster management agencies (BPBDs) and CSOs to facilitate community knowledge and behaviour change. This definition highlights DRM related support to local communities to enhance their abilities particularly to improve their knowledge and change their behaviour. The term ‘self-reliance’ has the connotation that communities – equipped with sufficient and appropriate know how and able to prepare and mitigate disasters in their locality – can rely on their own in times of disasters. This may not be realistic and implies a rather one-way interaction from outsiders to local people. The definition has further a static view on disaster events. We like to propose a different term and definition for the kind of community abilities and relationships with outsiders that we are looking for considering that this analysis conceives CBDRM in a political and institutional context.

Communities affected by disasters not only want to be better prepared and mitigate negative impacts, they also want to recover from past disaster events and adapt to new circumstances. The environment in which people live and the nature of disasters change continuously, due to climate change and the mounting vulnerability to which communities are exposed. Communities alone can’t solve all their risk problems. Disasters are complex problems that require collective and multi-sectoral responses from different agencies and institutions. Therefore local communities need to engage with other DRM actors to influence government’s policy and performance and to demand for safety and protection. Instead of the notion ‘self-reliance’, it is more appropriate to use the notion ‘resilience’ instead, emphasizing that multiple actors have a role and responsibility in providing security and safety before, during and after disasters strike. Community resilience would then be defined as “ability of communities to effectively anticipate, respond and adapt to disasters and transform interactions with government into functioning institutions and good DRM governance”.

AIFDR is particularly interested in replicable and sustainable CBDRM approaches. Concepts like ‘sustainability’, ‘replication’ and ‘up-scaling’ require further explanation and definition to arrive at a common understanding and to steer the analysis. ‘Replication’ refers to reproducing, repeating or transferring something to somewhere or somebody else. In the context of CBDRM approaches to achieve community resilience, ‘replication’ occurs first in terms of expanding the geographical coverage – e.g. from four villages to adjacent villages, and from one district to other districts. This happens through mobilizing social action and establishing CBO-networks. When increase in geographical coverage is combined with institutional embedding – e.g. when CBO-networks link with functioning BPBDs and coordination among BPBDs exist, then we of speak of ‘up-scaling’. Up-scaling transpires when organizational performance of BPBDs and BNBP improves as well as their DRM-related interactions. Up-scaling refers to replication both in terms of spatial coverage and government’s accountability from local to national level until CBDRM is institutionalized in the national socio-economic and spatial development planning and implementation.

The notion of ‘sustainability’ - like in ‘sustainable develop ment’ - originally referred to reconciling environmental, social and economic demands. But what sustainabi lity is, what its goals should be, and how these goals are to be achieved are all open to inter pretation. Sustainability is studied and managed over many scales of time and space, and in many contexts of environmental, social and economic organization. In the context of this analysis, we refer to ‘sustainable CBDRM approaches’, meaning embedding (CB)DRM into ‘institutional homes’ and establishing mechanisms that sustain human and financial resources locally and nationally to support (CB)DRM. ‘Institutional homes’ refer to the wide variety of institutions and actors at local, district to national level that take on their roles and responsibi li ties before, during and after disasters. ‘Institutional homes’ also refer to people’s and government’s mind-sets promoting a culture of safety, and to the performance of DRM actors towards reducing disaster risks and people’s vulnerability to future hazards. The process of embedding CBDRM into institutional homes is referred to as mainstreaming.

Replication - expanding the geographical coverage of CBDRM practice from one community to another through mobilizing social action and establishing CBO-networks (horizontal linkage building)

Up-scaling – increase in geographical coverage combined with institutional embedding through horizontal and vertical linkage building between CBO-networks, NGOs and government from district to national level

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 11

1.3 Research questions

The overall aim for the Community Resilience Analysis is to identify and describe effective and sustainable approaches that link government, CSOs, communities and private sector efforts in DRM with the aim to build community resilience. From the scope of the analysis1 and the literature review on CBDRM in Indonesia we arrived at the following research questions:

How is CBDRM defined by different actors and operationalized in practice?

This question investigates how the various actors like local people, religious leaders,

government agencies, private sector, and other actors conceive, negotiate, and implement (CB) DRM policy, and determine which choices for risk management are made. This question deals with the CBDRM process and explains why different interpretations of CBDRM exist.

How do the various actors view and interact in the (CB)DRM spaces to realize their interests?

This question investigates what kind of (CB)DRM spaces exist, the power relations among the various actors, how they view each other, and the different approaches they take and capacity they have to engage and interact with one another. This question deals with policy processes which are political and non-linear in nature, driven by diverse interests and incentives. It looks into the obstacles and opportunities for cooperation, for transforming power relations and institutions in favour of marginalized groups to build com muni ty self-reliance. This question deals with CBDRM key-outcomes considering social inclusion and gender.

What are effective approaches and the pre-requisites for building community resilience?

The findings from the previous two questions will steer further analysis into the potential roles and responsibilities in DRM of different actors at the various administrative levels to build community resilience and into effective strategies and approaches to ensure that the different actors take on these roles and responsibilities to make DRM a sustainable effort.

In answering above questions, both internal and external process factors will be considered. Internal process factors refer to the mandate, scope and capacity of communities, CSOs and government. External process factors refer to the governance context, institutions and state-society relationships in the selected areas. Communities and CSOs interact with other stakeholders in a particular local institutional setting and governance context. It is through these interactions that interventions and outcomes get shaped. In this light, an actor-orientation is chosen because it offers an analytical framework for studying policy, implementation and its outcomes. It further offers a framework to study both the specificities of particular local settings, and the broader forces and processes of institutional and societal change. The latter is crucial to assess whether or not approaches that are effective in one context are replicable in another context.

1.4 Conceptual framework

An actor orientation helps to clarify how DRM policies and interventions are shaped by the various actors involved in CBDRM. The actor-oriented approach starts from the premise that all actors are able to reflect upon their experiences and what happens around them, and use their knowledge and capabilities to interpret and respond to their environment (Long, 1992). People devise ways of coping with life, even under the most extreme forms of coercion. They use their knowledge, skills, influence, aspirations and organizing capacities in their problem-solving, survival and development strategies.

Although people have alternative options to shape their coping strategies and to formulate their objectives, these strategies are culturally embedded in different perceptions, interests and power relations. This implies that people’s options are favoured or constrained by their social position in society and prevailing cultural norms. Local people’s perspectives on risks and disaster events therefore vary greatly across regions, within villages, and between men and women among others. This results in competing risk and knowledge claims.

In the light of building community resilience, this analysis aims to assess how CBDRM interventions add to people’s capability to realize safety and protection by engaging with the broader institutional environment. Communities alone cannot solve all their risk problems and village authorities do not operate at the appropriate administrative level to address all urgent risk problems nor the underlying risk factors. Therefore local people need to engage with the broader institutional context, working across scales and in partnerships. Horizontal linkages with other Community-Based Organisations (CBOs) can be instrumental for early warning, sharing the lobbying workload, portraying shared concerns and for greater legitimacy as local representatives, and it supports in settling disputes and reducing tensions between communities. Vertical connections with authorities and power-holders have the potential that local voices are heard at district, provincial and national level, and to access financial resources for disaster risk reduction. These forms of linkage building refer to ‘social action’, to the ability of local people to make a difference to pre-existing state of affairs or course of events. In this process, four key principles, namely ‘social action’, ‘working across scales’, ‘reworking institutional arrangements’ and ‘partnership approach’ play an important role to foster community resilience through CBDRM. ‘Social action’ rests on the emergence of a network of actors, whether formal or informal, through routines or new organizing practices, and is bounded by prevailing norms, values and power relations.

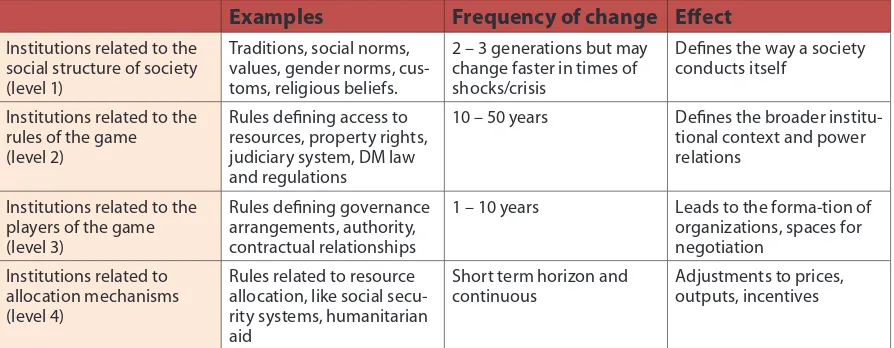

This analysis is not limited to local realities of communities and households. It equally focuses on the constraints put upon ‘social action’ to understand the larger structures in society, which is needed to assess the potential of CBDRM interventions in the proper context (Booth, 1994). The larger structures and constraints are referred to as ‘institutions’. Institutions include traditions, social norms, values, laws and regulations, policies and judicial systems regulating power relations, which are influenced by histori cal trajectories. Consequently, particular institutional arrangements work in one context but fail in another (Jutting, 2003). Institutions are crucial in regulating – for the better or the worse – access to resources, social protection, livelihood security, the maintenance of social order, and the handling of disputes at the local level (Alinovi et al, 2008). Institutions include power relations, and it is important to understand who benefits from the institutions, who sets the rules, and who is excluded. Disaster out comes can change these institutions and re-order power relations, the rules and interaction between people (Hilhorst, 2007).

What do (CB)DRM interventions do?

Governmental and Non-Governmental aid agencies and their interventions are part of the

institutional context as well. Local governments, NGOs and their donors do not operate in isolation, but are embedded in their respective context. To improve the conditions of disaster-affected populations, aid agencies formulate policy to express what they want to do and what results they intend to achieve. This section aims to provide analytical tools to study policy processes and interventions.

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 13

refers to how people use language to give meaning and make sense of events and experiences around them, and how they use language as discursive means to shape people’s beliefs and to convince others (Gaventa, 2006). People use ‘frames’ strategically to deal with actors who do not necessarily share the same values or views, but with whom it is crucial to maintain relationships. The various DRM actors like donors, government officials, NGO networks, media, the private sector and local communities, have their own language, rules, routines and demands (Hilhorst, 2003: 217). They use multiple ‘frames’ to set and use policy to find legitimacy for the organization’s presence and work and to deal with multiple accounta bilities. DRM actors need to convince others that what they do is relevant, indispensable and appro priate. They use language like ‘vulnerable groups’, ‘participation’, ‘partnerships’, ‘integrated approaches’ and ‘community resilience’ in official documents to create an image of an active involvement of disaster-affected populations in the interventions, to legitimize the organizations’ existence and their eligibility for funding. Policy documents and logical frameworks, however, hide assumptions about how change happens taking an idealistic view on the desirability and manageability of social change (Quarles van Ufford, 1993). This analysis aims to uncover several of these assumptions.

Logical frameworks do not problematize the relationships between the different actors and assume that programme activities are implemented in isolation from local contexts. CBDRM interventions shouldn’t be viewed as planned projects with a defined time-space setting that starts in a village on a blank page. Instead, interventions can best be regarded as part of the flow of events, as a series of encounters where different actors pursue, negotiate, debate and struggle for their interests and agendas to deal with multiple realities (ibid; Bakewell, 2000; Colebatch, 2002). Quarles van Ufford (1993) refers to the ‘political arena model’ as opposite to the ‘logical framework model’. As stated earlier, actors interpret and define the circumstances differently, and risk perspectives vary greatly. As a consequence CBDRM interventions are continuously re-defined and re-shaped according to those actors who can best negotiate their risk solutions. Therefore, interventions

inherently produce unpredictable outcomes. ‘Political arenas’ or ‘DRM dialogue spaces2’ are social

locations or situations where DRM actors confront each other, resist ideas, debate issues, resources and values, and try to resolve discrepancies in value interpretations and incompatibilities between actor interests. This analysis will reflect on how policy intentions are implemented in practice, how different perspectives on risk and risk reduction shape interventions, and how the various actors use their power to attain their goals. This ‘push and pull’ result in differing CBDRM practice and cooperation outcomes locally.

Studying ‘DRM dialogue spaces’

Disasters are events to which political systems must respond, and therefore “within minutes after any major impact, disasters start becoming political” (Olson, 2000:266). The way governments manage disaster risk, respond to and explain disasters, influences their interactions and relationships with their citizens. DRM is an area of public policy, but one that differs a lot from sectoral areas like education or health. DRM is not a sectoral issue but requires the involvement of a range of public sector agencies at different levels of government (Wilkinson, 2012). Governments not only provide goods and services to reduce disaster risks like early warning, shelters, first aid or mangrove belts, they can also engage in activities to influence the performance of others. To examine the institutional influences on DRM policy and practice, it is useful to divide government measures into categories and roles they can play in DRM3:

(1) Governments as providers of DRM goods and services;

(2) Governments as risk avoiders, meaning refrain from actions that generate risks

(3) Governments as regulators of private sector activity to reduce and avoid risks (4) Governments as promoters of collective action and private sector activity (5) Governments as coordinators of multi-stakeholder activities

These different roles involve public sector agencies that are not used to work collectively on cross-cutting issues. The nature of collaboration depends on how power is dispersed horizontally and vertically across government4. Decentralization reforms in Indonesia have given greater authority and responsibi lity to local governments, but not necessarily with the corresponding budgets resulting in so-called unfunded mandates. In addition, local governments have strong incentives to support the interests of local business and other private groups, which are often in opposition to the interests of vulnerable groups. Understanding disaster politics, power relations and incentives is key to assess the ‘room for manoeuvre’ of different DRM actors and approaches to work together to build community self-reliance.

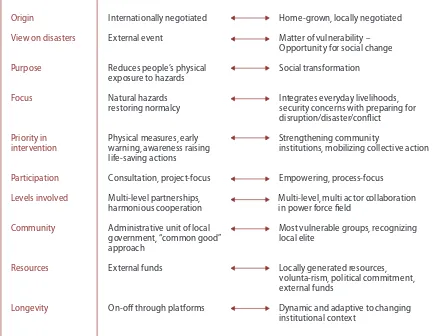

DRM is not just the responsibility of governments; resources are also distributed by (I)NGOs,

corporations, religious organizations, media, universities, unions and other institutions. These actors interpret disaster events, their circumstances and what is happening around them differently. Local people, NGOs and state-actors use their agency to convince the other of their explanation of events, their risk definitions, whom to blame and how to allocate resources when they negotiate, confront each other about issues, values and resources. They further attach different meanings to CBDRM and to ‘doing CBDRM’. For some, CBDRM means developing technical solu tions to improve early warning systems and emergency shelter at the local level, while for others CBDRM is a governance and human rights issue (Wisner & Walker, 2005b). A review of the origins of CBDRM traditions since the 1970s reveals that the CBDRM approach does not exist5. CBDRM practices are embedded in a broader institutional context of state-civil society relationships which constrain or enable local actors to advance their risk solutions. CBDRM is a contested approach with different interpretations and divergent practices. Figure 1. shows the implicit interpretations and worldviews behind the UN-promoted CBDRM tradition laid down in the Hyogo Framework for Action on the left side of the arrows, and the home-grown CBDRM traditions on the right side. In reality, CBDRM practice switches between the two CBDRM extremes as visualised through their features in the continua in Figure 1. Although the UN has recognized the importance of involving local communities in disaster risk reduction, its CBDRM-tradition still resonates a lot with top-down, short-term and isolated responses. In particular, the political connotation that was essential to the original con ception of CBDRM

has become marginal to mainstream CBDRM practice. Behind a shared CBDRM language, home-grown and mainstream CBDRM-traditions represent different origins that attach radically different meanings to CBDRM and the related concepts. The home-grown CBDRM views disasters as the outcome of weak governance, while the mainstream CBDRM views disasters as external events disrupting and undermining development investments (Bankoff & Hilhorst, 2009). Both CBDRR-traditions support people to build their resilience to disasters. The mainstream CBDRR does so through risk awareness raising, disaster preparedness, physical measures, safety-net mechanisms and institutional reforms, among others, while the home-grown CBDRM regards disasters as an opportunity for social change, therefore viewing CBDRM as a long-term community empowering process to enable vulnerable groups to demand safety and protection. CBDRM is a contested approach, not simply because people cannot agree on a common definition, but because they have different worldviews and intentions in mind that determine their actions.

4 See Draft Political Economy Analysis of DRM in Indonesia

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 15

The community resilience analysis seeks to understand what meaning different DRM actors attach to CBDRM, which intentions they have that determine their actions, and in what way CBDRM processes reduce, produce or reproduce people’s vulnerability to disasters. This is important to make informed decisions about which processes of building linkages and partnerships should be supported by donors and in what way, and which undesired processes need to be addressed.

Figure 1: Nature of CBDRR traditions expressed through their primary features on the continua

Origin

View on disasters

Purpose

Focus

Priority in intervention

Participation Levels involved

Community

Resources

Longevity

Internationally negotiated Home-grown, locally negotiated

External event Matter of vulnerability –

Opportunity for social change

Reduces people’s physical Social transformation exposure to hazards

Natural hazards Integrates everyday livelihoods, restoring normalcy security concerns with preparing for

disruption/disaster/conflict

Physical measures, early Strengthening community

warning, awareness raising institutions, mobilizing collective action life-saving actions

Consultation, project-focus Empowering, process-focus

Multi-level partnerships, Multi-level, multi actor collaboration harmonious cooperation in power force field

Administrative unit of local Most vulnerable groups, recognizing government, “common good” local elite

approach

External funds Locally generated resources, volunta-rism, political commitment, external funds

1.5 Scope and methodology for the analysis

This research involves different levels of analysis, stakeholders and areas. The focus is on CBDRM practices in Indonesia, and its potential and limitations to build community resilience in partnership with government. The field visits zoom into CBDRM practices in West Aceh, East Java, Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT) and West Sumatra and how disaster-affected populations deal with disaster risks and relate to CSOs, government and the private sector.

Levels of analysis

Community level: CBDRM efforts are supposed to generate change at the village level in terms of vulnerability reduction, sustainable livelihoods and community resilience. Village authorities and CBOs were interviewed to discuss the local risk context, causes of risks, coping mechanisms and initiatives taken by the community, relations between village authorities and CBOs, nature of risk reduction measures necessary and implemented, effect of these measures, community initiatives to engage with other actors to reduce risk, integration of risk reduction measures into Village Development Planning (Musrenbang) are among key issues. The findings of community level discussions will serve as concrete reference cases for the interviews with stakeholders at higher administrative levels.

District level: CSO field staff and managers interact with each other and with other CSOs,

government officials, knowledge centres, media and the private sector from the local to the district and even higher administrative levels. This level of analysis draws lessons and insights regarding processes, structures, collaboration, interaction, effectiveness and relevance of multi-stakeholder processes in DRM and fostering community resilience with the district BPBD as key actor.This analysis will further reveal how the actors at district levels perceive CBDRM.

Provincial level: At this level, lessons and insights are drawn regarding political decision-making and resource allocation regarding DRM and CBDRM in particularly from national to local levels. Where do top-down and bottom-up DRM approaches meet and what are the constraints to embed CBDRM in government’s mainstream development policies and planning processes.

Since the focus is on fostering community resilience and reducing risk at the local level, this research puts local people’s risk perspectives as the entry point and the centre of analysis. This means that the interviews and analysis started at the local level followed by a ‘study up’, mirroring local priorities and risk solutions to policies and DRM practices from district level to provincial and national levels. This reveals disconnects and opportunities in matching DRM policy and responses with local realities. On the other hand, it maps the various expectations and assumptions the different actors have about each other regarding roles and responsibilities in DRM.

The research team consisted of two external consultants (one international and one Indonesian) and AIFDR staff who participated in the field visits for data collection and analysis. The consultants bring with them previous research experience on CBDRM policy and practice in different parts of Indonesia like Aceh, Central Java, West Java, West Sumatra, Yogyakarta, Kalimantan, NTT and Maluku which is also used in the analysis.

Desktop review

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 17

Analysis of the DRM sector in Indonesia, a Rapid Organisational Assessment of the National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB) and of a sample of Sub-National Disaster Management Agencies (BPBD), a Study on Social Inclusion and Gender, and a CBDRM Realist Review. Insights and conclusions from these studies were considered in our interviews and analysis. In addition, a desktop review was conducted on international best practices in CBDRM with a focus on sustainable approaches and/or evidence of CBDRM replication.

Field visits and semi-structured interviews

Qualitative methods for data collection and analysis were applied like participatory observation, ocular visits and face-to face meetings with key actors using semi-structured interviews. Key informants for focus group discussions and interviews were identified among community

representatives, non-government and government institutions at different levels, in collaboration with AIFDR team. We further had interviews with media, faith-based organizations and the private sector.

At the village level we talked to CBOs and disaster preparedness teams (youth, women, farmers, fishermen, teachers and health workers), village authorities and informal leaders and religious organizations. At the provincial and district level interviewees come from BPBD, Bappeda, NGOs, media, schools, and university (research centre).

The first field visits to West Aceh, East Java and Nusa Tenggara Timur took place from 11-19 December 2012 while the second field visits to East Java and West Sumatra occurred from 21-25 January 2013.

1.6 Structure of the report

Chapter 2 presents the state of affairs of CBDRM in Indonesia based on a desktop review and interviews conducted with Jakarta-based organisations.

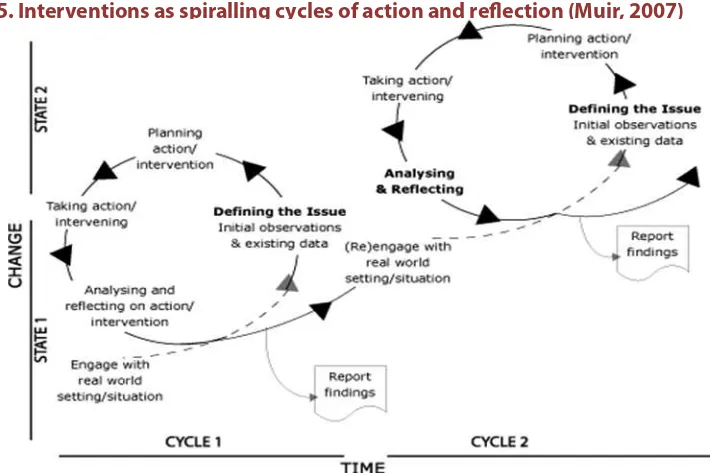

Chapter 3 provides an overview of the key findings collected during the field visits with an emphasis on effective strategies to achieve community resilience that we observed in the field and which we compared with case studies in relevant literature.

In chapter 4 we formulated a theory of change and a roadmap based on empirical data and literature that may assist AIFDR to find appropriate entry points and strategies to build linkages among different DRM actors and for creating DRM dialogue spaces to enhance DRM governance in selected provinces. This section elaborates on the rationale for area selection, criteria for community selection, and on the kinds of partnerships that would be most effective in achieving this change. The roadmap will assist AIFDR to identify its role and added value in achieving this change.

2. Situational analysis of CBDRM in Indonesia –

challenges, gaps and needs

In 2011, AIFDR commissioned a review of existing CBDRM initiatives in Indonesia to get an

understanding of ‘who does what and where’ in the CBDRM space in Indonesia, what the challenges are, gaps and needs are, and to get a clear idea about where AIFDR should position itself. This review forms the basis for this analysis. This situational analysis put CBDRM in the broader institutional and political context of Indonesia to understand the nature of relationships between the government and civil society – particularly at the local level - from a historical perspective. It is based on CBDRM literature review, various NGO reports and on interviews with Jakarta-based organizations conducted in January 2013. The analysis provides an overview of the DRM-landscape in Indonesia since the tsunami in 2004, the progress made regarding CBDRM practices and their key-outcomes, NGO capacities to engage with government, and forms of networks that exist. The chapter ends with the challenges, gaps and needs for the future.

2.1 The broader political and institutional context of Indonesia

related to DRM

After the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the fall of President Suharto in 1998, Indonesia started political reforms creating new opportunities for a revised relationship between the state and local communities. The New Order’s centralistic and uniform framework was replaced by a new legal frame work for the democratisation of local-level politics and village institutions (Antlöv, 2003). During the New Order, Suharto’s central government was in full control in supervising village governance, where the village head was in fact an instrument to the central government. Village heads were directly accountable to the sub-district head, not to the villagers. Village administrations usually consisting of the local elite - enforced policies and decrees formulated in Jakarta. Since they had to be loyal to the state party, Golkar, they were forced to maintain good relations with higher authorities, at the expense of relations with the local population (Antlöv, 2010: 196).

According to the new Law 22/1999, the village is no longer under the authority of the sub-district, but became an autonomous level of government. This means that a village can formulate and pass its own village regulations and budgets without the approval from higher authorities. The village administration now consists of a village head, his staff and the Badan Perwakilan Desa (BPD), the village parliament, which is elected from and by the villagers. The village head is no longer obliged to be oriented to the upward government structures, but is accountable to the villagers and to the BPD. The law provides the framework for what is legally possible, but one has to look at how the law gets implemented in practice to know whether the possibilities are realised. Many village governments are not yet aware about the space for own initiatives like DRM measures, while in other villages, the local elite is not yet willing to fundamentally change existing power relations.

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 19

Suharto’s time, civil-society organizations had to operate under heavy regulations and repression, preventing labourers, farmers and fishermen to organize themselves to oppose government policies (Antlöv, 2003), whereas nowadays they are less afraid to speak out their concerns or dissatisfaction. The space for civil society to lobby and engage with government for more structural DRM policies increased since the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. This major disaster event triggered a paradigm shift in the mind-set of the Indonesian Govern ment from reactive emergency relief towards efforts for more pro-active disaster preparedness and mitigations (Barnaby Willitts-King, 2009). Also many new NGOs were established in response to the tsunami with a mandate to assist communities in their recovery and to reduce future disaster risks (Régnier et al, 2008). A month after the tsunami, the GoI was one of the 168 governments worldwide that signed the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA). This provided a push for reform, which coincided with on-going lobby efforts of UNDP and the Indonesian Society for Disaster Management, known as MPBI (Lassa 2011). MPBI is an association and comprises UN staff, government officials, NGO activists and academics. It successfully lobbied for a more proactive DM law to reduce the immense losses like experienced during recent major disasters in the country stressing to look into causes of disasters and not only into impact. This new DM law 24, enacted in July 2007, is integrated in the decentralization policies, meaning that power to formulate DRM policies for its respective territory is delegated to the district and village government levels. The law prescribes that DRM policies should be in line with development policies, and include disaster management cooperation policies with other districts, provinces or cities.

Whereas the MPBI was able to mobilize different DRM actors and to successfully advocate for the ratification of the DM Law No 27/2007, its role weakened due to a lack of funding, declining influence and reduction in membership, possibly due to the establishment of a new (competing) National DRR Platform, PLANAS, as mandated by the new DM Law with the secretariat hosted within BNBP6 (Djalante, 2012). PLANAS took an active role and became a leading forum for DRR advocacy between 2007-2009 particularly abroad where PLANAS represented Indonesia’s experience in reconstruction processes following big disaster events (ibid). The role of PLANAS became less clear when DM policy and institutional frameworks were put in place at the national level, and the enthusiasm of its members seems to decrease (Hillman and Sagala, 2011). Vertical links between PLANAS and local level multi-stakeholder networks seem to be non-existing, which forms a gap in the institutional development and DRM performance, since national platforms could gain legitimacy and recognition through the involvement and feedback mechanisms from the grassroots level. The national disaster management framework still contains crucial ambiguities in terms of concepts (exact meaning of disaster management), organisational structure (National and Regional Disaster Management Bodies), process and procedures. These ambiguities affect regional government’s adoption of the framework and its translation into regional policies and instruments. Civil society operating at these local levels can make use of these ambiguities which provide room for negotiating how government from the village to district level could translate disaster risk reduction policy into practice. In next section, we will elaborate on DRM practices at local levels, and their key-outcomes.

2.2 Local level DRM practices in Indonesia

Community-based approaches to DRM are relatively new in Indonesia, compared to countries like the Philippines or Bangladesh where CBDRM has proven its value. In Bangladesh, cyclones today only cause a fraction of formerly experienced deaths, thanks to shelters, early warning mechanisms and evacuation, and in finding appropriate risk reduction measures. CBDRM in Indonesia is being

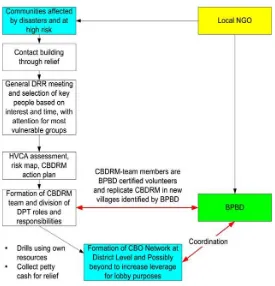

implemented by a wide range of DRM actors like local NGOs, INGOs, Red Cross Societies, faith-based organizations (NU, 2010), the private sector, universities7 and also BNBP has its ‘desa tangguh’ program. The majority of these actors adopted and adapted the CBDRM concepts that are available inter nationally like the ADPC Field Practitioner’s Handbook on CBDRM (Abarquez and Murshed, 2004). Local NGOs which are partners of an INGO or national NGO received training on CBDRM based on international CBDRM materials which conceptualize CBDRM as a linear process starting with a risk assessment which includes a Hazard Vulnerability Capacity Assessment (HCVA), the formulation of a communicy action plan including a contingency plan, the formation of a disaster preparedness team and the conduct of evacuation simulations to test the skills and knowledge gained (Nakmofa & Lassa, 2009). Many NGOs assume sustainability of CBDRM by linkage building with BPBDs and by some financial support to realize simple mitigation measures by way of exit strategies. An exit strategy could consist of integrating the community action plan in the village development plan to ensure that village resources could be accessed. In reality, village budgets can hardly accommodate DRM measures and a need exists to look for funds beyond the community level which is often a challenge. BNPB’s ‘desa tangguh’ program follows the same process but on a very limited scale (42 villages nation-wide).

Key-outcome of this CBDRM approach is the creation of CBDRM-teams at village level which are able to warn their community-members and to safely evacuate vulnerable groups in times of disasters. The communities that are selected for this CBDRM approach have experienced disaster events in the past. Examples are volcano prone areas like Mt. Merapi and Mt. Kelud where recent eruptions happened, and in tsunami and earthquake affected areas in Yogyakarta, West Sumatra and Aceh. These communities are more likely to be motivated to invest in disaster preparedness than communities which have not yet experienced disasters. Local people are eager to learn skills and approaches that reduce the number of casualties and damage.

CBDRM as a project instead of community empowering process

Looking at the different CBDRM-traditions in figure 1 (chapter 1), it can be concluded that most DRM actors in Indonesia view CBDRM as a project instead of a community empowerment process. NGOs use the logframe for measuring progress and success. For instance, when CBDRM-teams are formed and evacuation drills are conducted, the CBDRM-intervention is regarded as successful, stressing the usage of participatory tools, enhancement of community early warning systems and evacuation plans - which substantially led to increase community preparedness (Lassa, 2012; Hillman and Sagala, 2010). Viewing CBDRM as a community empowerment process and an approach for institutional development is still rare in Indonesia. The intended shift of the DM law to focus on the underlying causes of disasters and less on their impact has not yet transpired.

A key-element of CBDRM policy is that communities need to take an active role in the identification of their risk problems and in the decision-making of what should be done to solve these using terms like ‘participation ’and ‘local ownership’. The project-oriented CBDRM approach actually consists of preconceived activities without room for changes or adaptations based on local risk perspectives. ‘Participation’ rather means involving people in project activities which is assumed to make interventions more efficient, and people are mainly ‘empowered’ in terms of forming community organizations, a type and level of empowerment that poses no serious threat to prevailing power relations (Bebbington et al 2007: 598). ‘People’s participation’ is here not meant to question or confront power inequalities nor to transform institutional arrangements to reduce disaster

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 21

vulnerability, but that people act as volunteers to do the work on behalf of government to save resources. The project-oriented CBDRM approach largely ignores the social, economic and political origins of disaster vulnerability still ‘seeing’ disasters as sudden, external events. When CBDRM implementation gets delayed, NGOs attribute this to ‘communication barriers’ between facilitators and (in)formal leaders in the village. However, CBDRM interventions, like any intervention, involves negotiation, debates and struggles over resources and interests (see conceptual framework) which requires time to arrive at appropriate risk solutions. CBDRM interventions do not start on a blank page, isolated from the broader context.

But many NGOs assume they do: instead of exploring the capacities of CBOs, and other forms of social capital, new CBDRM structures are established. NGOs do not fully recognize existing community structures, institutions or local knowledge. Most rural communities in Indonesia

understand very well the potential risks; they have their specific coping strategies to deal with threats from natural hazards. Yet, such strategies are not fully integrated in current CBDRM practices while these are crucial when searching for more sustainable CBDRM interventions. Particularly this is due to facilitators’ lack of capacity to contextualize the CBDRM text book into practice. Another weakness observed by Djalante (2012) is that DRM actors at the local level can’t access the abundance of material published on lessons learned, and also systematic learning from past practices is not developed locally by decision-makers.

Although communities are involved in the CBDRM process, they don’t seem to experience a shift in mind-set meaning that they still view their vulnerable position in society as unchangeable, accepting prevailing norms, values and institutions that legitimate current relationships and arrangements. Even when CBDRM-teams are linked to local government, it remains unclear how such partnership can guarantee sustainability or achieve community resilience. The CBDRM-teams are not equipped with leadership skills, like lobby and negotiation skills or speaking in public. They often don’t know where to go for additional DRM support. Nevertheless, there are a few good case studies that can be referred to as empowering CBDRM approaches that improve community resilience, like CBDRM practices in Muria Region, Central Java, implemented by four local NGOs linked through the Muria Coalition8, while also the CBDRM approach applied by the Partners for Resilience seems promising. These approaches aim to rework and develop institutional arrangements with government, engage with BPBDs and relevant line departments in their lobby and dialogue efforts, which remains a challenge and require efforts beyond project-timeframes.

In Muria Region, Central Java, for instance, decentralisation of powers to the district level makes it difficult for flood-affected communities to address environmental issues and inappropriate land use in their watershed which covers three districts. Land use planning and watershed management are issues still being decided at higher levels. Provinces still have autonomy in spatial planning, public works, and environmental issues, among others, and the national level keeps the responsibility for natural resources. Whereas Pati district has a DRM plan and policy since July 2010, the adjacent districts lack any DRM policy or structure making inter-district cooperation almost impossible. Aside of the lack of knowledge and understanding of the new responsibilities at the various government levels and departments concerning DRR, the decentralization did not result in the decentralization of revenues. This implies that districts can set their priorities but are not sure whether they will have the funding for implementation. This is another constraint for the district government to not invest in big projects like river normalization. In the end, it remains unclear what exactly has been decentralised (Schulte-Nordholt, 2003) which prevent district governments to look beyond investments in

evacuation shelters and awareness raising initiatives on disaster preparedness. This example shows the importance of institutional reform at different administrative levels and the urgent need of local communities to engage with local government with the support of civil society. However, vertical links between DRR platforms hardly exist, and even district level forum are rare (Djalante, 2012).

School-based approaches to reduce disaster risk

School-based approaches are applied by NGOs that focus on children as their entry points, such as World Vision (2010), Plan International (2010) and Save the Children. The NGOs with their local partners normally incorporate teachers, children and their parents in the activities. School-based approaches also focus on disaster preparedness through simulations. Often this is supported by mainstreaming DRR into their curricula translated to the local context. Theoretically, this is ideal but it reveals that some teachers would like to have ‘ready-to-use’ materials rather than to develop the local content themselves. In terms of partnership, school-based management (manajemen berbasis sekolah) is applied by involving the department of education, BPBD, the school committee and teachers which later approach and advocate to parliament members. Another approach is by having a headmaster forum at district level where they can share information on school safety and DRM. The school- based approach to CBDRM could also be a stepping-stone to conduct disaster prearedness training in nearby communities.

2.3 Capacity of NGOs to work with government and to link

communities with government

Many NGOs (local and international) confirm that local government (BPBD) plays a significant role in achieving and sustaining long term community resilience. Yet, NGOs observe that the support from local government to CBDRM is minimal. The usual interaction between NGOs and local govern ment occurs when the NGO initiates CBDRM projects and informs the authorities about this initiative. BPBDs are hardly involved during CBDRM implementation, while on the other hand, some NGOs expect that the CBDRM programmes will eventually be supported by BPBD’s annual budget. Such expectations are not realistic, knowing that many BPBDs are newly established agencies with limitation in staff capacity, financial resources and facilities. Some BPBDs expect NGOs to continue and expand their programs in the district, which is also an unrealistic expectation. Also the presence of INGOs in disaster prone areas raises expectations, since the local government (BPBD) notices that INGOs brings knowledge and programmes to the communities. It would help when NGOs and local govern ment would meet more often and in a more substantial way to exchange their expectations, even when it is just to discover that what each party assumes is impossible. Dialogue spaces, both informal and formal, are very much needed to advance CBDRM practice and policy. Some DRR forum at provincial or district level exist, but many do not function well. Many lack the proper representation from community-based organizations, or have limited financial support, unclear purposes and lack of leadership (Djalante, 2012).

There are some good examples where local governments have been linked with communities through CBDRM programs. Communities near Mt. Kelud have been recognized by the local govern-ment as active CBOs organized into a network called Jangkar Kelud, which supports disaster

C O M M U N I T Y S E L F - R E L I A N C E A N A LY S I S | PA G E 2 3

were able to negotiate and have dialogues with (illegal) miners and village authorities (Heijmans, 2012). In Meulaboh and Ende districts, the coastal communities managed to construct sandbags as a mitigation measure against sea waves and coastal erosion with the involvement of local government. However, not so many local NGOs consider it their task to link communities with local governments (Lassa, 2009). Many CBDRM programs end without interaction between communities and local government, because NGOs think that support from local government is limited, so they do not encourage communities to negotiate or engage local government because they don’t want to create false hope. These kinds of NGOs’ mind-sets will not lead to community resilience.

A special sector involved in CBDRM in Indonesia are the faith-based organizations such as Nahdlatul Ulama, Muhammadiyah and Catholic Church Networks. They are active in the regions where the majority of the population belongs to their constituency where they raise awareness about disasters and enhance preparedness. For this purpose they use existing structures that are embedded in community life: Nahdlatul Ulama f.i. approaches ustadz (cleric) and kyai (chaplain) to convince communities to take part in disaster preparedness activities in East Java. In NTT, Caristas Maumere, the Catholic Church NGO organization approach rural communities to develop their disaster action plan. The advantage of these networks is that contact and trust building – like applied by NGOs – is not necessary because the facilitators live in the community, which allows informal and long term facilitation. Additionally, faith-based organizations can influence members of parliament and govern-ment who are their followers to be supportive to DRM. Faith-based organizations easily provide a platform where the needs of the communities can be communicated to local governments and parliaments.

2.4 Challenges, gaps and needs

While disaster preparedness has been significantly improved since 2004, challenges remain. The immense area and number of communities in Indonesia exposed to multiple hazards urge for up-scaling CBDRM activities. However, the unique context of each community in Indonesia makes it difficult to know how to best replicate CBDRM to promote a culture of safety nation-wide. Differing cultural settings may cause some CBDRM activities succeed in one region but fail in another.

Therefore it is crucial to always understand local settings first and to recognize local risk perspectives even when people experience the same disaster event as elsewhere. Additionally, communities often prioritize economic and livelihood concerns and support for addressing the underlying risk factors over preparedness measures resulting in a mismatch between responses offered and people’s urgent felt needs. So far, CBDRM in Indonesia is dominated by external funding, which puts questions about the sustainability of CBDRM approaches on the long run. In addition to that, partnerships between NGOs, CBOs and local government remain limited for the duration of a project since each actor has it’s own mandate and style. The idea to integrate CBDRM activities into local development processes is still a huge challenge since the timeframe of CBDRM activities do not typically meet the development planning cycle. Further, the integration of CBDRM into the development planning process requires high level support, starting from village, sub-district and district government to get engaged in the process and to support the proposed programme. Another challenge is the limited involvement of the private sector and media in supporting DRM in communities.

Gaps

However, the necessary capacities of BPBDs to sustain CBDRM initiatives are not yet in place. In term of resources, communities are told that they could access resources from line departments or through private sector’ CSR programmes. But these are still dreams because not so many CSR programmes support DRR at community level, and also line departments do not easily provide funds for DRM to communities.

Partnerships between communities and local government through DRR forum are still rare. There are examples where a forum was created through a formal process (under Governor Bill), but no activities happen like in Nusa Tenggara Timur Province. Additionally, many communities lack the capacities to mobilize effective agency and form networks to negotiate with government.

Needs

3. Overview of key findings and observations from the

field visits

The research team visited communities in Kediri and Blitar districts situated near Mount Kelud, an active volcano, communities in Bojonegoro district affected by floods from the Bengawan Solo River, and a coastal community in Banyuwangi district, East Java province, four communities in Sikka and Maumere Districts, NTT affected by tsunami, earthquakes, coastal erosion, flooding, droughts, three communi ties in West Aceh and three in West Sumatra affected by tsunami, earthquakes and floods. After community visits, interviews were conducted with NGO staff and district-level BPBDs. The findings are structured according to the different levels of analysis starting with the community since local people’s perspectives are the entry-point and centre of the community self-reliance analysis.

3.1 How is CBDRM defined and operationalized in practice?

Community-level analysis: local risk perspectives and priorities

East Java - We visited four villages (Besowo, Satak, Widang and Soso) that are located on the slopes of Mount Kelud in East Java, which erupted in 2007. The government forced the villagers to evacuate because the BMKG predicted a severe eruption. The villagers reluctantly left their homes; “We have our own indicators for deciding whether to evacuate or not and who should be evacuated”. “We were put in evacuation centers and treated as cattle”. “We just slept and waited to be fed”. “Aid providers could have asked us to cook ourselves. We tried to organize ourselves to change the situation. But we were regarded as helpless victims while we are not”. The relief responses provided by the government were below humanita rian standards, chaotic and corrupt, according to the villagers, and they felt that this should change. These negative experiences formed their motivation to engage with Kappala, a Yogyakarta-based NGO, which acted as facilitator to organize the villagers in a more systematic way using their social and motivational capacities while promoting a culture of solidarity-fraternity.

Initially, interested people coming from 10 villages attended training on CBDRM which focused on organizing and mobilizing other villagers into Disaster Preparedness Teams. These teams founded Jangkar Kelud in 2008 – an independent, informal organization consisting of organized communities. At this moment 38 villages belonging to three districts (Kediri, Blitar and Malang) are part of Jangkar Kelud with 1820 active members. These members are responsible to replicate CBDRM training in other villages around Mount Kelud and to maintain a level of disaster preparedness through simulations, and sharing experiences through a radio-network. For Jangkar Kelud CBDRM means solidarity, helping each other beyond emergency periods, using their existing capacities and being organized in Disaster Preparedness Teams (Coordinator, Treasurer, Early Warning team (through radio and walky talkies), search and rescue team, training team (especially teachers), health team, kitchen team). Additionally, Jangkar Kelud – based on its negative experience in 2007 – considers its role to lobby and negotiate with districts government to have local villagers’ perspective included in DRM planning and decision-making, to change the mind-set of BPBDs and to enhance their coordina tion responsibility. A challenge for Jangkar Kelud is to reach the most vulnerable households who live in remote places and who lack resources or time to attend training or meetings. It is Jangkar Kelud’s long-term effort to expand to these areas and to look for people with the capacity to become a local facilitator.