Pro

ASP.NET 4 CMS

Advanced Techniques for C# Developers

Using the .NET 4 Framework

Alan Harris

Learn the latest features of .NET 4 to build

powerful ASP.NET 4 web applications

US $42.99

www.apress.com

Advanced Techniques for C# Developers

Using the .NET 4 Framework

■ ■ ■

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner and the publisher.

ISBN-13 (pbk): 978-1-4302-2712-0

ISBN-13 (electronic): 978-1-4302-2713-7

Printed and bound in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Trademarked names, logos, and images may appear in this book. Rather than use a trademark symbol with every occurrence of a trademarked name, logo, or image we use the names, logos, and images only in an editorial fashion and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark.

The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights.

President and Publisher: Paul Manning

Lead Editor: Ewan Buckingham, Matthew Moodie Technical Reviewer: Jeff Sanders

Editorial Board: Clay Andres, Steve Anglin, Mark Beckner, Ewan Buckingham, Gary Cornell, Jonathan Gennick, Jonathan Hassell, Michelle Lowman, Matthew Moodie, Duncan Parkes, Jeffrey Pepper, Frank Pohlmann, Douglas Pundick, Ben Renow-Clarke, Dominic

Shakeshaft, Matt Wade, Tom Welsh Coordinating Editor: Anne Collett Copy Editor: Kim Wimpsett Compositor: MacPS, LLC

Indexer: BIM Indexing & Proofreading Services Artist: April Milne

Cover Designer: Anna Ishchenko

Distributed to the book trade worldwide by Springer Science+Business Media, LLC., 233 Spring Street, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10013. Phone 1-800-SPRINGER, fax (201) 348-4505, e-mail [email protected], or visit www.springeronline.com.

For information on translations, please e-mail [email protected], or visit www.apress.com.

Apress and friends of ED books may be purchased in bulk for academic, corporate, or promotional use. eBook versions and licenses are also available for most titles. For more information, reference our Special Bulk Sales–eBook Licensing web page at www.apress.com/info/bulksales.

The information in this book is distributed on an “as is” basis, without warranty. Although every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this work, neither the author(s) nor Apress shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in this work.

■

Contents at a Glance ... iv

■

Contents ... v

■

About the Author ... xii

■

About the Technical Reviewer... xiii

■

Acknowledgments... xiv

■

Introduction ... xv

■

Chapter 1: Visual Studio 2010 and .NET 4...1

■

Chapter 2: CMS Architecture and Development ...29

■

Chapter 3: Parallelization...47

■

Chapter 4: Managed Extensibility Framework and

the Dynamic Language Runtime...103

■

Chapter 5: jQuery and Ajax in the Presentation Tier ...135

■

Chapter 6: Distributed Caching via Memcached ...165

■

Chapter 7: Scripting via IronPython ...197

■

Chapter 8: Performance Tuning, Configuration, and Debugging...229

■

Chapter 9: Search Engine Optimization and Accessibility ...257

■

Contents at a Glance ... iv

■

Contents ... v

■

About the Author ... xii

■

About the Technical Reviewer... xiii

■

Acknowledgments... xiv

■

Introduction... xv

■

Chapter 1: Visual Studio 2010 and .NET 4...1

Who This Book Is For ... 1

Who This Book Is Not For (or “Buy Me Now, Read Me Later”)... 2

What’s New in .NET 4... 2

C# Optional and Named Parameters ...3

C#’s dynamic Keyword...5

Dynamic and Functional Language Support ...10

Parallel Processing ...10

Managed Extensibility Framework (MEF)...13

Distributed Caching with Velocity ...13

ASP.NET MVC ...16

A Tour of Visual Studio 2010... 18

Windows Presentation Foundation ...18

Historical Debugging...19

Improved JavaScript IntelliSense...21

Building a CMS... 24

CMS Functional Requirements...24

Creating the Application Framework ...25

Summary... 28

■

Chapter 2:

CMS Architecture and Development ...29

Motivations for Building a CMS... 29

Motivations for Using .NET... 30

Application Architecture... 30

The CMS Application Tiers ...32

CommonLibrary: The Data Transfer Objects ...33

GlobalModule: The HttpModule ...35

Components of a CMS Page... 37

Buckets ...37

Embeddable Objects ...39

Embeddable Permissions...41

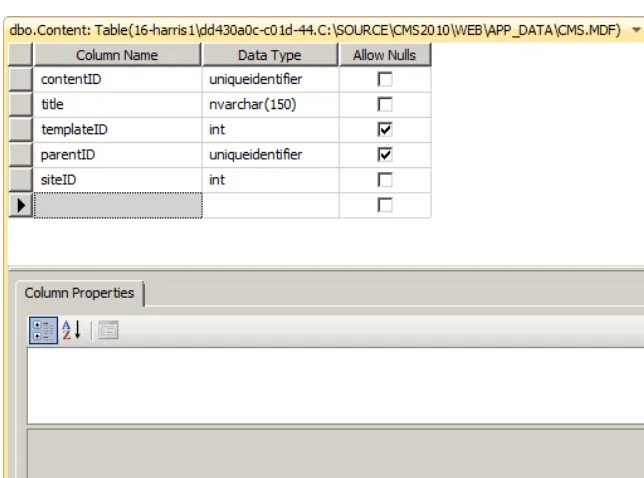

Handling CMS Content ... 43

The Content Table ...43

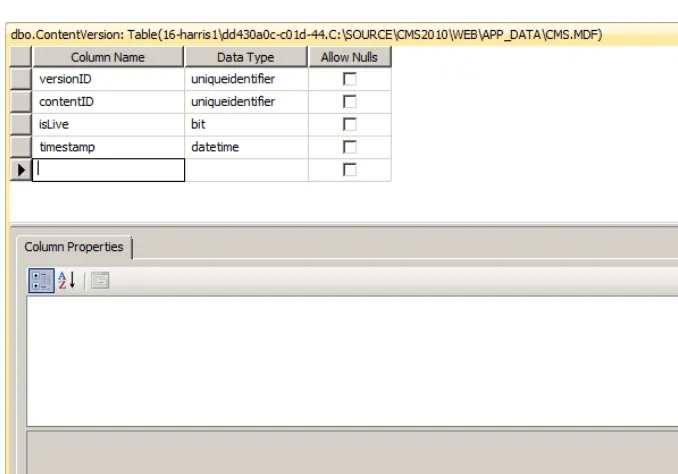

The ContentVersion Table ...44

Assembling Content on Demand...44

How Embeddable Objects Handle Versions ...46

Summary... 46

■

Chapter 3: Parallelization...47

What Is Parallelization?... 47

Good Parallelization Candidates...47

Differences from Multithreading ...48

Parallel Pitfalls ... 48

Deadlocks ...48

Race Conditions ...51

Amdahl’s Law ...55

.NET 4 Parallelization Concepts ... 56

Task vs. Data Parallelism...56

Task Parallel Library ... 56

Task.Wait() ...57

Parallel.For() and Parallel.ForEach()...59

Parallel LINQ (aka PLINQ) ... 59

.AsParallel() ...60

CMS Parallelization Opportunities... 61

Creating a Data Mining Embeddable...62

Expanding the Data Mining Tasks...66

Tagging ... 70

Tagging on the Client ...73

Fleshing Out the Tagging Embeddable ...75

What’s in a Name? ...76

Handling Tag Input ...79

Tag Processing in the Business Tier ...82

POST Problems ...87

Finalizing Tag Storage ...89

Inserting Tags ...92

Content Tags ...96

Summary... 102

■

Chapter 4:

Managed Extensibility Framework and

the Dynamic Language Runtime...103

Managed Extensibility Framework... 103

The Manual Way...103

The MEF Way ...105

Working from Usage to Implementation ...106

Exposing Libraries via MEF ...106

Implementing the Plug-In...107

Using the Plug-In...108

Catalogs and Containers ...112

Supporting Multiple Parts ...113

Dynamic Language Runtime ... 117

The dynamic Keyword...118

Benefits of the dynamic Keyword ...119

CMS Plug-Ins ... 120

IEmbeddable ...121

Server Controls as Embeddables ...122

Displaying Embeddables...124

PageAssembler ...125

Additional Methodology Benefits ... 128

Missing DLLs...128

Exceptions in Embeddables ...129

A More Complex Emeddable ... 130

Breadcrumbs...130

Navigating the CMS Tree ...131

Summary... 133

■

Chapter 5: jQuery and Ajax in the Presentation Tier ...135

An Introduction to jQuery ... 135

The $() Factory ...136

Implicit Iteration ...138

Ajax via jQuery ... 139

Caching and Ajax ...140

Avoiding Caching on GET Requests ...141

Lightweight Content Delivery with Ajax and HTTP Handlers...142

Handling Asynchronous Errors...147

Handling DOM Modifications...150

Creating Collapsible Panels ...156

Expanding with jQuery ...158

Displaying the JavaScript Disabled Message ...160

Poka-Yoke Devices ... 161

Summary... 164

■

Chapter 6: Distributed Caching via Memcached ...165

What Is a Distributed Cache, and Why Is it Important?... 165

Memcached ... 166

Acquiring a Memcached Client Library ...167

Getting Started with Memcached ...168

Complex Object Types...178

Protocol Considerations ...181

Memcached Internals and Monitoring ...183

Building a Cache-Friendly Site Tree... 185

Visualizing the Tree...186

Defining a Node...186

Defining the Tree...187

Finding Nodes ...188

Inserting Nodes ...190

Serializing/Deserializing the Tree for Memcached Storage...191

Memcached Configuration Considerations ... 194

Summary... 196

■

Chapter 7: Scripting via IronPython ...197

How Does the CMS Benefit from Scripting Capabilities?... 197

Easier Debugging ...197

Rapid Prototyping...198

An Introduction to IronPython and Its Syntax... 198

What Is IronPython? ...198

The IronPython Type System ...200

Creating Classes and Controlling Scope ...203

Constructors as Magic Methods ...206

self ...207

Exception Handling ...211

Conditional Logic, Iterators, and Collections...214

Accessors and Mutators ...216

Assembly Compilation... 217

Compiling IronPython Code to a DLL...218

Compiling IronPython Code to an Executable ...219

Building Scripting Capabilities into the CMS... 220

Handling Script Files Between Tiers ...223

Calling Scripts for a CMS Page ...224

A Simple Scripting Example...226

Summary... 228

■

Chapter 8:

Performance Tuning, Configuration, and Debugging...229

The CMS Definition of Performance... 229

Latency...229

Throughput...230

Establishing Baselines ... 230

Component vs. System Baselines ...230

The Web Capacity Analysis Tool ... 231

Installing WCAT ...231

WCAT Concepts...231

Configurations...232

Scenarios ...233

Running a WCAT Test Against the CMS ...235

Interpreting Performance Results ...236

Improving CMS Performance with Caching ... 237

Benchmarking CMS Performance ...238

Configuration Considerations... 239

Enable Release Mode for Production ...239

Removing the Server, X-Powered-By, and X-AspNet-Version Headers ...241

Debugging Concepts ... 244

White-Box vs. Black-Box Debuggers ...244

User Mode vs. Kernel Mode ...245

Historical Debugging via IntelliTrace ... 246

Collaborative Debugging... 250

Importing and Exporting Breakpoints ...250

DataTip Pinning and Annotation...253

Summary... 256

■

Chapter 9: Search Engine Optimization and Accessibility ...257

An Introduction to Search Engine Optimization ... 257

Science or Dark Art? ...258

General Guidelines ...258

Friendly URLs ... 265

Data Requirements for Friendly URLs ...265

Stored Procedures for Friendly URLs ...268

Exploiting the Page Life Cycle...269

Request Exclusion...271

Retrieving Friendly URLs...273

Retrieving Alias URLs and Response.RedirectPermanent()...279

Summary... 283

About the Author

■ Alan Harris is the senior web developer for the Council of Better Business Bureaus. He also regularly contributes to the IBM developerWorks community where he writes “The Strange Tales of a Polyglot Developer.” Alan has been developing software professionally for almost ten years and is responsible for the development of the CMS that now handles the high volume of users that the CBBB sees every day. He has experience at the desktop, firmware, and web levels, and in a past life he worked on naval safety equipment that made use of the Iridium and ORBCOMM satellite systems.

Alan is a Microsoft Certified Technology Specialist for ASP .NET 3.5 Web Applications. Outside of the IT realm, he is an accomplished Krav Maga and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu practictioner, as well as a musician.

About the Technical Reviewer

■ Jeff Sanders is a published author and an accomplished technologist. He is currently employed with Avanade Federal Services in the capacity of a group manager/senior architect, as well as the manager of the Federal Office of Learning and Development. Jeff has 17+ years of professional experience in the field of IT and strategic business consulting, in roles ranging from leading sales to delivery efforts. He

regularly contributes to certification and product roadmap development with Microsoft and speaks publicly on technology. With his roots in software development, Jeff’s areas of expertise include operational intelligence, collaboration and content management solutions, distributed component-based application architectures, object-oriented analysis and design, and enterprise integration patterns and designs.

Jeff is also the CTO of DynamicShift, a client-focused organization specializing in Microsoft

technologies, specifically Business Activity Monitoring, BizTalk Server, SharePoint Server, StreamInsight, Windows Azure, AppFabric, Commerce Server, and .NET. He is a Microsoft Certified Trainer and leads DynamicShift in both training and consulting efforts.

Acknowledgments

To my friends, family, and co-workers: thank you for sticking with me through another book as well as the development of the CMS. It’s been a long process but a rewarding one; I hope I haven’t been too unbearable along the way.

To the team at Apress: thank you for your help, invaluable suggestions, and continual patience while I developed an enterprise system and a book in lockstep. You gave me the freedom to make the system what it needed to be and to write a book that supports that vision.

To the great people at KravWorks: thank you for providing me with an environment where I can grow as both a fighter and a person. The experiences I’ve had within the walls of the school are unlike anything I’ve encountered anywhere else, and they’ve made me better than I was before. You will always have my respect.

Introduction

I started down the road of building a content management system (CMS) as a direct result of the experiences I had working with another custom CMS in my day-to-day work. A handful of design decisions made at the conception of that system years ago greatly impacted the CMS from a development standpoint; some things worked exceptionally well, some things needed additional love and care to achieve the results we really wanted, and some things were outright broken.

As usual, hindsight is 20/20; although the system had carried us for years, the code base was so huge and so intertwined that rewriting it was the only cost-effective solution. Even simple maintenance tasks and feature development were increasingly resource-prohibitive. I set off on a skunkworks project to create the CMS while the remaining developers kept the existing one chugging along.

It’s a truly difficult decision to throw away code. A lot of developers worked on the previous CMS over the years, and a completely new system brings with it a unique set of challenges. I wasn’t only throwing the old code away; I was throwing away the applied project experience, the accumulated developer-hours spent working with it, and so on. It’s the shortest path to incurring significant design debt that I can think of, and incur I most certainly did: the CMS was developed from the ground up over the course of approximately a year.

The end result is a CMS that the development team is happier working with, that management can trust will be stable and dependable, and that users find both responsive and fully featured. It’s not perfect, but luckily, no system is. If there were such a thing, someone would’ve built it, and we’d all be out of jobs. What I’ve tried to do is build a system that met the evolving business needs of my organization and write a book to accompany it that acts as a guided tour of both the new .NET features and how they click together in the context of a CMS. It has proven to be a very interesting ride, indeed.

A tremendous benefit to the creation of both the system and the book was the early preview and beta of Visual Studio 2010 and .NET 4.0. Case in point: as you’ll see, the new Managed Extensibility Framework makes up a significant part of the business logic in the CMS (and VS2010, which uses MEF for its add-on capabilities). Could the CMS have been built without .NET 4? Of course, it could have been, but I would venture to say that it would not be as robust or as feature-complete given the timeframe.

I can think of a dozen ways to accomplish any of the results shown by the CMS in this book. What I have attempted here is to demonstrate the methods that worked for me in a production environment, using a system that is concrete rather than theoretical, and with the newest technology Microsoft has to offer as the method of transportation.

About This Book

This book is fundamentally a companion text as much as it is an introduction. A content management system is a nontrivial piece of software with many “moving pieces.” As such, it would be next to impossible to document the usage of each and every line of code in a meaningful way while still giving adequate coverage to the topics new to .NET 4.0.

Along the way, I’ve tried to highlight useful bits of information (or pitfalls) that mark the way from design to implementation.

What You Need to Use This Book

This book assumes that you have a copy of Visual Studio 2010, .NET 4.0, and a web browser at your disposal. It also assumes that you have a copy of the source code to the CMS.

Code Samples

The source code for this book is available from the Apress website. The CMS core is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License; this means that you, the reader, are free to copy, distribute, and transmit the work as well as adapt it for use in your own projects if you so desire. This license does require attribution if you want to launch a CMS of your own based on the core; otherwise, it’s yours to do with as you please.

Feedback

■ ■ ■

Visual Studio 2010 and .NET 4

“If the automobile had followed the same development cycle as the computer, a Rolls-Royce would today cost $100, get a million miles per gallon, and explode once a year, killing everyone inside.”

—Robert X. Cringely

It has been eight years since Microsoft released the first version of the .NET Framework and Visual Studio to the world. In the interim, developers have found new and innovative ways to create tremendously powerful software with these tools, and Microsoft in turn has listened carefully to developer feedback, effectively putting the feature set and methodology into the hands of the people who will use it on a daily basis. The number and quality of tools in this latest version speak highly to that decision.

Now on version 4 of the .NET Framework, Microsoft has radically improved the developer experience while maintaining the core framework that so many have become comfortable with. As the framework has evolved over time, Microsoft has done an excellent job of preserving the functional core while adding impressive components on top, thereby reducing or eliminating breaking changes in most cases, which not only eases the upgrade process for developers but serves as an excellent bullet point for IT managers who must weigh the risks of infrastructure upgrade with the benefits of the newest versions of the framework.

■Note The last release with potential breaking changes was version 2.0 of the framework; versions 1.0 and 1.1 of .NET were solid releases, but developer feedback resulted in several sweeping changes. That said, the breaking changes were limited, and since then components have been added, not removed or significantly modified.

Who This Book Is For

system as well as how to apply new .NET 4 features to its development, we'll be moving at a pace that assumes web development is already fairly natural for you.

Further, although we will be focusing mainly on C#, there are situations where C# is not the best language in which to express a solution to a particular problem, and there are so many great choices available in .NET 4 that it’s almost criminal to ignore them. When a new language or tool is introduced, we’ll take some time to cover its syntax and capabilities before applying it to the CMS, so you don’t need to be a complete .NET polyglot expert before tackling those sections.

■Caution I am using the Team System edition of Visual Studio 2010 for the writing of this book because there are components to the IDE that are made available only through that particular edition. If you’re using Professional or Express versions of any of these tools, there will be certain components you won’t be able to use. I will highlight these areas for you and do my best to make things functional for you even if you’re not using the same version. The most notable difference is the lack of historical debugging in versions below Team System.

Who This Book Is Not For (or “Buy Me Now, Read Me Later”)

If you have no experience in a .NET language (either C# or VB .NET) or no experience with the concepts behind web development (such as HTTP requests, the page life cycle, and so on), I would wager that you’ll be in some conceptually deep water fairly quickly, and you probably won’t enjoy the experience much. This book is aimed at the intermediate to advanced .NET developer who is interested in learning about the newest version of .NET and Visual Studio as well as the application of some of Microsoft’s more interesting fringe projects that are in development at this time. You do need some familiarity with the tools and languages this book is based on; I recommend spending some time learning about C# and ASP.NET and then returning to see some examples of new Microsoft technology that makes theexperience more enjoyable.

What’s New in .NET 4

Before we jump into Visual Studio, let’s take a look at the new features and tools that come with .NET 4. For now we’ll take a quick look at each topic, effectively creating a preview of the contents of the rest of the book. Each topic will be covered in greater detail as we explore how to apply it to the design of the CMS (which you’ll learn about at the end of this chapter).

■Note The Common Language Runtime (CLR) is Microsoft’s implementation of the Common Language Infrastructure (CLI). The CLI is an open standard that defines how different languages can compile to an

intermediate bytecode for execution on virtual machines on various platforms. Essentially, C#, VB .NET, and other .NET languages compile to Common Intermediate Language (CIL) and are executed by the CLR. This means that any platform with an implementation of the CLR can execute your code with zero changes. This is a powerful new direction for software development and allows you an essentially platform-agnostic viewpoint as a developer; the exceptions are fringe cases involving pointers, unmanaged code, and types that deal with 32-bit versus 64-bit addresses, and the majority of the time you are unlikely to encounter them (unless unmanaged code is your thing, of course).

C# Optional and Named Parameters

We’ve all encountered development scenarios where a “one-method-fits-all” solution isn’t quite right. Perhaps in one instance it makes sense to rely on some default value; an example might be hiding database connection details behind a GetConnection() class that uses the one and only connection string defined in your application. If you need to add more connection strings to the application, you could overload this method like in Listing 1–1.

Listing 1–1. A Set of Database Connection Method Overloads

/// <summary>

/// Returns a SQL connection object using the default connection string "CMS". /// </summary>

public SqlConnection GetConnection() {

return new SqlConnection(ConfigurationManager.ConnectionStrings["CMS"].ConnectionString); }

/// <summary>

/// Returns a SQL connection object using a supplied connection string. /// </summary>

/// <param name="conStr">A connection string of type string</param> public SqlConnection GetConnection(string conStr)

{

return new

SqlConnection(ConfigurationManager.ConnectionStrings[conStr].ConnectionString); }

■Tip Generally, it's a better practice to code to an interface, not a concrete class. By that I mean if you create a data layer entirely using SqlConnection and SqlCommand objects, you will have some work ahead of you if you decide to swap to Oracle or CouchDB. I typically use IDbConnection as the method type for this reason, but the example is less cluttered if I stick with the more familiar SqlConnection (which does implement IDbConnection), so I think breaking the rules in this case is justified. Throughout the book we’ll be using the SQL Server-specific classes in all cases.

In my experience, major database shifts are not frequent occurrences, but your particular situation may benefit from additional flexibility.

That’s a perfectly acceptable solution and a clean way to do things, but the code base is larger for it. With .NET 4, C# now supports optional and named parameters, providing a cleaner method for

completing the same task (see Listing 1–2).

Listing 1–2. Handling the Connections in One Method with Optional Parameters

/// <summary>

/// Returns a SQL connection object using the default "CMS" connection if none is provided. /// </summary>

public SqlConnection GetConnection(string conStr="CMS") {

return new

SqlConnection(ConfigurationManager.ConnectionStrings[conStr].ConnectionString); }

SqlConnection conn = GetConnection(); // uses the default connection string SqlConnection conn2 = GetConnection("CMS2"); // uses the optional parameter

■Note You could accomplish the same task with a nonoptional string parameter and check its state within the method; however, I think you’ll agree that the whole solution is simpler and more elegant with the optional parameter. A very large portion of software programming in most languages is devoted to “defensive

programming”: checking boundaries, value existence, and so on. Optional methods essentially remove lines of defensive code and thereby reduce the number of areas a bug can hide.

If you have a method that has multiple optional parameters, you can provide names for the parameters you do want to supply in the form (name : value), as shown in Listing 1–3.

Listing 1–3. A Method with Required and Optional Parameters

/// <summary>

/// </summary>

/// <param name="id">an integer ID</param>

/// <param name="foo">a string value; defaults to "bar"</param> /// <param name="initial">a character initial; defaults to 'a'</param> public static void Test(int id, string foo="bar", char initial='a') {

Console.WriteLine("ID: {0}", id); Console.WriteLine("Foo: {0}", foo);

Console.WriteLine("Initial: {0}", initial); }

Test(1, initial : 'z');

As you can see in Figure 1–1, although a default value for Initial was supplied in the method signature, it is optional, and therefore a supplied value from a call will override it.

Figure 1–1. We supplied the required parameter and one of the optional ones using a name.

■Tip Named parameters have to appear after required parameters in method calls; however, they can be provided in any order therein.

C#’s dynamic Keyword

from any assembly that implements that interface and act on it accordingly. It’s certainly a powerful tool in the .NET arsenal, but .NET 4 opens new doors via the dynamic keyword.

Suppose we have a third-party library whose sole function is to reverse a string of text for us. We have to examine it first to learn what methods are available. Consider the example in Listing 1–4 and Figure 1–2.

■Note This reflection example is adapted from a blog post by the excellent Scott Hanselman, the principal program manager at Microsoft and an all-around nice guy. You can find his blog post on the subject of the C# dynamic keyword at http://www.hanselman.com/blog/C4AndTheDynamicKeywordWhirlwindTour AroundNET4AndVisualStudio2010Beta1.aspx.

Listing 1–4. The Methods to Square Numbers Using an Outside Library

object reverseLib = InitReverseLib(); type reverseType = reverseLib.GetType(); object output = reverseType.InvokeMember( "FlipString",

BindingFlags.InvokeMethod, null,

new object[] { "No, sir, away! A papaya war is on!" }); Console.WriteLine(output.ToString());

Figure 1–2. Flipped using reflection to get at the proper method

Reflection, although extremely functional, is really rather ugly. It’s a lot of syntax to get at a simple notion: method A wants to call method B in some library somewhere. Watch how C# simplifies that work now in Listing 1–5.

Listing 1–5. Using the dynamic Keyword to Accomplish the Same Thing

dynamic reverseLib = InitReverseLib();

Console.WriteLine(reverseLib.FlipString("No, sir, away! A papaya war is on!"));

So, where’s the magic here…what’s happening under the hood? Let’s see what Visual Studio has to say on the matter by hovering over the dynamic keyword (see Figure 1–3).

Figure 1–3. The Visual Studio tooltip gives a peek at what’s really going on.

Essentially, the dynamic type is actually static, but the actual resolution is performed at runtime. That’s pretty cool stuff, eliminating a large amount of boilerplate code and letting your C# code talk to a wide variety of external code without concern about the guts of how to actually start the conversation. The application of this concept doesn’t have to be so abstract; let’s look at a more concrete example using strictly managed C# code.

Assume we have a abstract base class called CustomFileType that we use to expose common functionality across our application wherever files are involved. We’ll create a CMSFile class that inherits from CustomFileType. A simple implementation might look like Listing 1–6.

Listing 1–6. A CustomFileType Abstract Base Class

public abstract class CustomFileType {

public string Filename { get; set; } public int Size { get; set; } public string Author { get; set; } }

public class CMSFile : CustomFileType {

// …some fancy implementation details specific to CMSFile. }

Now if we want to act on this information and display it to the screen, we can create a method that accepts a dynamic parameter, as shown in Listing 1–7.

Listing 1–7. A Method to Display This Information That Accepts a Dynamic Type

/// <summary>

/// Displays information about a CustomFileType. /// </summary>

{

Console.WriteLine("Filename: {0}", fileObject.Filename); Console.WriteLine("File Size: {0}", fileObject.Size); Console.WriteLine("Author: {0}", fileObject.Author); Console.ReadLine();

}

■Tip Notice when using XML comments that Visual Studio treats dynamic parameters just like any other. Therefore, since the type is resolved at runtime, it’s not a bad idea to indicate in the param tag that the object is dynamic so that you and others are aware of it when the method is used.

If we call this method providing a CMSFile object, the output is really quite interesting (see Listing 1– 8 and Figure 1–4).

Listing 1–8. Calling Our Method with a Dynamic Object

static void Main(string[] args) {

DisplayFileInformation(new CMSFile{Filename="testfile.cms", Size=100, Author="Alan Harris"});

}

Figure 1–4. The results of a method accepting a dynamic type

The experienced developer at this point is shouting at the page, “You could accomplish the same thing with a method like static void DisplayFileInformation(CustomFileType fileObject).” This is true to a point; this falls apart once you begin to deal with classes that do not specifically inherit from

CustomFileType but perhaps have the same properties and methods. The use of the dynamic keyword allows you to supply any object that has an appropriate footprint; were you to rely solely on the

CustomFileType object in the method signature, you would be forced to either create multiple overloads for different object parameters or force all your classes to inherit from that singular abstract base class. The dynamic keyword lets you express more with less.

Consider Listing 1–9; assuming we have two classes, FileTypeOne and FileTypeTwo, that do not inherit from a common base class or interface, the DisplayFileInformation method that accepts a specific type (FileTypeOne) can operate only on the first file type class, despite that both classes have the same properties. The DisplayFileInformation method that accepts a dynamic type can operate on both classes interchangeably because they expose identical properties.

Listing 1–9. Demonstrating the Effectiveness of the Dynamic Keyword

public class FileTypeOne

/// Displays information about a file type without using the dynamic keyword. /// </summary>

/// <param name="fileObject">a FileTypeOne object </param> static void DisplayFileInformation(FileTypeOne fileObject) {

Console.WriteLine("Filename: {0}", fileObject.Filename); Console.WriteLine("File Size: {0}", fileObject.Size); Console.WriteLine("Author: {0}", fileObject.Author); Console.ReadLine();

}

/// <summary>

/// Displays information about a file type using the dynamic keyword. /// </summary>

/// <param name="fileObject">a dynamic object to be resolved at runtime</param> static void DisplayFileInformation(dynamic fileObject)

{

Console.WriteLine("Filename: {0}", fileObject.Filename); Console.WriteLine("File Size: {0}", fileObject.Size); Console.WriteLine("Author: {0}", fileObject.Author); Console.ReadLine();

Dynamic and Functional Language Support

If you have any experience with Python, Ruby, Erlang, or Haskell, you will be pleasantly surprised with .NET 4. Microsoft has had support for dynamic and functional languages for some time; however, it has always been through separate add-ons that were in development quite separately from the core

framework. First-class support is now available because the following languages are now included out of the box:

• IronPython

• IronRuby

• F#

■Note Don’t take this to mean that F# is a one-to-one equivalent of either Erlang or Haskell; indeed, F# is quite different from both of them. F# is simply the functional language of choice in the .NET ecosystem at the moment. We’ll cover functional versus procedural and object-oriented programming later in the book.

IronPython and IronRuby execute on the Dynamic Language Runtime (DLR). The DLR has existed for some time but now comprises a core component of the .NET Framework; the result is that

IronPython and IronRuby now stand alongside C# and VB .NET as full-fledged .NET languages for developers to take advantage of. Furthermore, if you have experience developing in Python or Ruby, the transition to .NET will be smooth because the language is fundamentally the same, with the addition of the powerful .NET Framework on top. Developers interested in working with functional programming languages will find F# to be a very capable entry into the .NET family; F# has been around for years and is able to handle some very complex processing tasks in an elegant fashion.

Parallel Processing

For several years now, it has been commonplace for even entry-level machines to have either multiple processors or multiple cores on the motherboard; this allows for more than one machine instruction to be executed at one time, increasing the processing ability of any particular machine. As we’ll see, this hardware trend has not escaped the notice of the Microsoft .NET team, because a considerable amount of development effort has clearly gone into the creation of languages and language extensions that are devoted solely to making effective use of the concurrent programming possibilities that exist in these types of system environments.

Parallel LINQ (PLINQ)

Language Integrated Query (LINQ) was first introduced into the .NET Framework in version 3.5. LINQ adds a few modifications to the Base Class Library that facilitate type inference and a statement structure similar to SQL that allows strongly typed data and object queries within a .NET language.

■Note The Base Class Library defines a variety of types and methods that allow common functionality to be exposed to all .NET languages; examples include file I/O and database access. True to form with the framework, the addition of LINQ classes to the BCL did not cause existing programs built with versions 2.0 or 3.0 to break, and PLINQ has been applied just as smoothly.

PLINQ queries implement the IParallelEnumerable<T> interface; as such, the runtime distributes the workload across available cores or processors. Listing 1–10 describes a typical LINQ query that uses the standard processing model.

Listing 1–10. A Simple LINQ Query in C#

return mySearch.Where(x => myCustomFilter(x));

Listing 1–11 shows the same query using the AsParallel() method to automatically split the processing load.

Listing 1–11. The Same LINQ Query Using the AsParallel() Method

return mySearch.AsParallel().Where(x => myCustomFilter(x));

PLINQ exposes a variety of methods and classes that facilitate easy access to the multicore

development model that we will explore later in the book, as well as ways to test the performance effects that parallelism has on our applications in different scenarios.

Task Parallel Library (TPL)

Not content to only expose convenient parallelism to developers using LINQ, Microsoft has also created the Task Parallel Library (TPL). The TPL provides constructs familiar to developers, such as For and ForEach loops, but calls them via the parallel libraries. The runtime handles the rest for you, hiding the details behind the abstraction. Listing 1–12 describes a typical for loop using operations that are fairly expensive in tight loops.

Listing 1–12. A for Loop in C# That Performs a Computationally Expensive Set of Operations

// declares an array of integers with 10,000 elements int[] myArray = new int[10000];

for(int index=0; index<10000; index++) {

// take the current index raised to the 3rd power and find the square root of it myArray[index] = Math.Sqrt(Math.Pow(myArray[index], 3));

Listing 1–13 shows the same query using the Parallel.For() method to automatically split the processing load.

Listing 1–13. The Same Loop Using TPL Methods

// declares an array of integers with 10,000 elements int[] myArray = new int[10000];

Parallel.For(0; 10000; delegate(int index) {

// take the current index raised to the 3rd power and find the square root of it myArray[index] = Math.Sqrt(Math.Pow(myArray[index], 3));

});

Does this shift in techniques automatically convey a matching increase in performance? You should already know the answer: “it depends.” Unfortunately, that’s a very accurate answer. A little testing usually reveals the truth, and we’ll learn how to do this shortly.

Axum

If you’re used to typical object-oriented development (particularly with C#), Axum is going to turn your coding perception on its head. With a syntax and set of constructs very similar to C#, Axum is designed to help developers who want to write message-passing, concurrent code that is thread-safe and easy to work with and test.

■Caution Axum remains a Microsoft incubation project; what this means is that support for it may be dropped at any time, plus any and all language features may change or be removed at any time. It’s such a strong and interesting development in parallel languages that it is certainly worth coverage. More to the point, as an incubation project, it is strongly driven by developer feedback, so let Microsoft know what you think of it; with sufficient support, the language should survive and becomes a first-class citizen of the .NET Framework.

You won’t find classes, structs, and many other C# entities in Axum. What you will find are agents that pass messages back and forth to one another. You can define millions of agents in a single application; they are designed to be extremely lightweight, much more so than typical threads. With Axum, you can create complex networks that communicate with one another asynchronously and in a highly scalable fashion, avoiding the overhead that comes with the traditional constructs of other languages. Axum is truly specialized to allow developers flexibility in creating massively scalable components and applications.

Axum has not yet been fully integrated into the .NET Framework but does plug directly into Visual Studio 2010 (and 2008 as well). It can be downloaded from the Microsoft DevLabs site at

■Note If you’ve ever worked in a language such as Erlang, the message-passing aspects and agents of Axum will be fairly familiar. Axum isn’t quite functional programming in the traditional sense, but the similarities are more than passing.

Managed Extensibility Framework (MEF)

Until .NET 4, developers who wanted to create a plug-in model for their applications were left with the task of creating an implementation and infrastructure from the ground up; it’s an attainable goal but potentially cost- and time-prohibitive. Microsoft’s answer to this situation is the Managed Extensibility Framework (MEF).

■Note Microsoft believes strongly in the MEF and in fact uses it under the hood of Visual Studio 2010 quite extensively. It introduces quite a bit of powerful add-on capability to the already extensible Visual Studio environment.

Fundamentally, MEF exposes ComposableParts, Imports, and Exports, which manage instances of extensions to your application. The MEF core provides methods to allow discovery of extensions and handles proper loading (as well as ensuring that extensions are loaded in the correct order). The nature of extensions is exposed via metadata and attributes, which should be very familiar territory to .NET developers and allows for a very consistent usage across .NET applications.

■Tip The concepts of reflection and metadata come up frequently in discussions regarding extensibility. Reflection gets a bad rap for being slow; it indeed is slower than direct calls, but generally you pay only an appreciable penalty when using reflection in tight loops or in a critical set of methods that get called far more frequently than others. Reflection is used quite liberally throughout the .NET Framework, but in an intelligent fashion and only where needed. Don’t write off a perfectly reasonable development solution because you’ve heard the worst of it; if nothing else, do a limited test, and use a profiler to get some hard numbers for your own edification.

Distributed Caching with Velocity

data in-memory; objects stored in the cache do not have to be retrieved from potentially expensive database calls, resulting in greater availability and a better distribution of workload.

■Note Hit ratio defines the number of times an object was successfully retrieved from the cache (a cache hit) versus how many times it could not be (a miss).

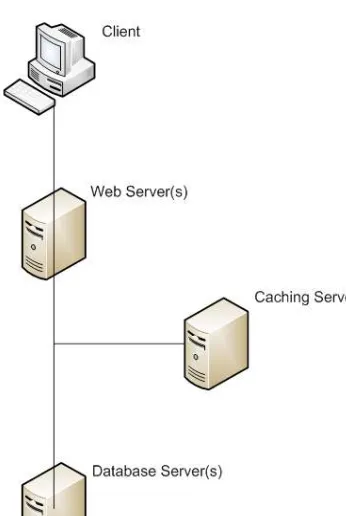

In a distributed environment, one or more caching servers sit separately from the web servers and database servers. The purpose of these servers is to provide extremely quick access to frequently used resources and data, reducing the load incurred by expensive database calls and operations. For example, once a user has logged in to your system, their personal information can be cached so that requests for that data do not need to be processed by the database; rather, they can be quickly looked up by key names and used by the application, eliminating one or more potentially costly database calls. Figure 1–5 shows the typical rough layout of a system involving distributed caching servers. Note that the caching server is a branch of the overall communication; the primary data store is still the database server, but the cache servers exist along this communication pathway as a potential source of the same information without the overhead of processing data to assemble it.

■Tip Figure 1–5 should illustrate just why it’s so important to have as high a hit ratio as possible: each time your code makes a request to the cache server and misses, your code has paid the performance penalty of the extra request without the benefit of returning with data and skipping the database call. Although it’s nearly impossible to get a 100 percent hit ratio (excluding the rare cases where you can prefill the cache before client requests are executed), there are patterns to ensure that you maximize these cache requests as quickly as possible.

Figure 1–5. The typical architecture of a system with distributed caching

Listing 1–14. A Pattern for Working with a Distributed Cache

// attempt to retrieve the value for "myKey" in the cache string myValue = CMSCache.Exists("myKey");

if (String.IsNullOrEmpty(myValue)) {

// the key did not exist, so fetch it from the data tier… myValue = CMSData.SomeDataCall();

// …and add it to the cache for retrieval next time with a 40 minute expiration. CMSCache.Add("myKey", myValue, 40);

}

■Tip With situations such as distributed caching, it’s a good idea to hide the implementation details of the cache behind a custom abstraction (in this case, CMSCache). If at some point you decide that Velocity is not for you and you would rather use Memcached or NCache, it’s much easier to modify or extend your caching classes than to modify every area in your application where caching is used. Save yourself the headache, and hide the guts out of sight.

The current version of Velocity is Community Technology Preview 3, available from the Microsoft site at http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/details.aspx?FamilyId=B24C3708-EEFF-4055-A867-19B5851E7CD2&displaylang=en.

ASP.NET MVC

Microsoft, since the inception of ASP.NET, has essentially stuck to its WebForms model with a single form element on a page, ViewState fields, and so on. The MVC framework, which stands for Model View Controller, is a pretty radical departure in the opposite direction and certainly one that developers have been requesting for quite some time. To understand why MVC is so significant, we need to examine the evolution and purpose of the WebForms model.

The traditional WebForms model is meant to solve the problem of maintaining state on a web page. By definition, the HTTP standard is stateless; before the advent of real server-side architecture, web pages were static affairs that were limited to displaying content and permitted basically no real user interaction, short of clicking links to go to other static pages. The WebForms model has served developers well over the years, but it’s not without warts and rough edges.

The most common complaint leveled at WebForms is that it is heavy and by no means optimized. Up until version 2.0 of the .NET Framework, the HTML output rendered by .NET controls (Buttons, GridViews, and so on) was in no way standards-compliant, and at the time the options were a bit limited in how to resolve these problems. In the years since, Microsoft has definitely cleaned the markup that standard .NET controls produce, but ViewState remains a critical component in the WebForms solution.

ViewState is Microsoft’s primary way of preserving state information between page requests. It consists of one or more hidden input fields (typically one, but ViewState chunking allows separation of the field into multiple fields) that contain an encoded set of information about the state of any and all .NET controls on the page. Sounds great, so what’s the problem?

■Tip Most of the time you won’t really need ViewState chunking; however, certain load balancers, reverse proxy, and firewall devices will choke on an HTML input field that is beyond a certain length. Chunking the field into some reasonable length usually resolves the problem immediately. You can experiment with different field lengths in the root web.config file of an application; an example would be <pages maxPageStateFieldLength="2048">, which will split the ViewState into an additional hidden input field at 2,048-byte divisions.

receives. Worse, the ViewState appears at the top of the page, potentially putting a large roadblock between you and content that is search engine–friendly; search engines typically index only a particular number of characters in a page’s content, and if 5,000 or more characters are wasted on content-less ViewState data, that’s 5,000 fewer characters that a potential audience could see.

■Tip Please don’t fall into the trap of assuming that ViewState is encrypted. It is not. It is encoded, and the difference is significant. There exist several ViewState decoders that will readily show you the contents of any particular ViewState data, and writing your own from scratch is a very doable task as well. Repeat after me: ViewState is not for sensitive information.

Model View Controller is designed to solve all those problems and return to .NET developers clean, standardized markup using traditional HTML elements as well as the complete elimination of ViewState. The Model aspect refers to the data source of the application, which for our purposes will be a SQL database. The Controller is the brain of the operation, fetching the appropriate information from the Model and feeding it to the View, which is our user interface.

MVC and WebForms are both based on ASP.NET, but they place value and importance on different things; where WebForms aim to provide a very rich, stateful application, MVC aims to operate in a way that mirrors the HTTP specifications. In the MVC world, the page itself is quite dumb, capable of very little without being told. The View relies on being fed complete state information from the Controller and makes no decisions on its own. The result is a clean separation of concerns, a lightweight page model, and 100 percent control over the markup on your applications.

You’re by no means limited to either MVC or the WebForms model; in fact, you’re quite free to mix and match within the same application. The emphasis in .NET moving forward is on options and choices, freeing developers from constraints and allowing them to make the choices that are most appropriate for the application at hand.

A Tour of Visual Studio 2010

Visual Studio 2010 is a major overhaul of the VS environment, no doubt about it. Not just a shiny coat of paint, the 2010 editions are a ground-up improvement, and as mentioned earlier, Microsoft is using many of its own .NET 4 tools and components within the IDE itself. Let’s take a 10,000-foot tour of the new 2010 IDE.

■Note IDE is short for “integrated development environment.” An IDE combines code editing, compilation, debugging, and more into one application. You are still free to perform many tasks via the command line if you choose (and many do), but the convenience of the IDE is quite impressive.

Windows Presentation Foundation

Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) first arrived with .NET 3.0. Using Extensible Application Markup Language (XAML), WPF allowed developers to create rich application interfaces with a level of quality and visual polish previously reserved for developers working with Flash and similar tools. In Visual Studio 2010, WPF is the driving force between the new user interface spit-and-polish that you see from the moment you spin up an instance of the IDE. It’s a powerful application of WPF to real-world development, and Visual Studio looks and feels like a very complete system with much attention paid to how the typical developer will use it. Figure 1–6 shows the IDE as it appears the first time you start it.

Figure 1–6. The new and improved Visual Studio 2010 IDE

Historical Debugging

Software development is generally a complex beast, even given the many tools and frameworks available to developers today. From thread management to distributed caching solutions, there are a lot of aspects in play at any given time, and getting everything to interact in such a fashion that the system runs correctly and efficiently requires a considerable effort.

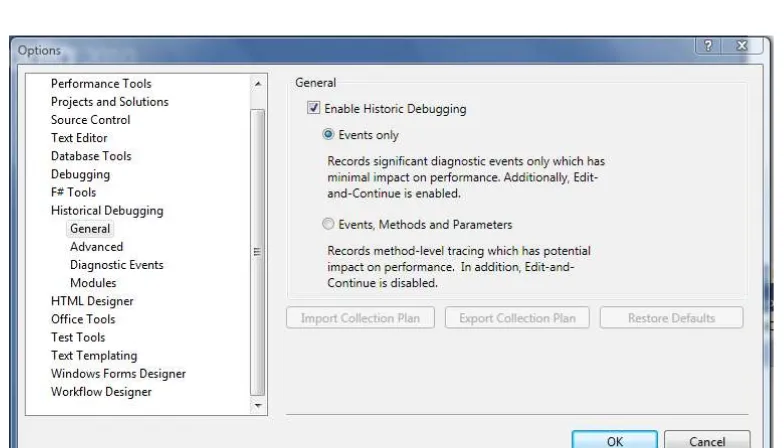

Historical debugging allows you to set specific events in your application where the debugger will collect data that represents a snapshot of the current application state, effectively allowing you to replay the application execution and determine precisely what was happening. Alternatively, you can opt to retrieve debugging information at all method entry points in your program. The focus on the historical debugger has really been on providing an in-depth debugging ability that is familiar to developers who are comfortable working with the Visual Studio debugger.

Quite a few configuration options are available when working with the historical debugger, and the Visual Studio team has paid a lot of careful attention to the effect that data collection has on application performance, which is part of the reason so many granular levels of options exist.

■Note Historical debugging is available only in the Team System edition of Visual Studio.

Figure 1–7. Historical debugging can be configured in various ways depending on your needs.

How critical is a good debugger and knowledge of how to use it effectively? Consider the following quote from a person far wiser than I:

“Debugging is twice as hard as writing code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are—by definition—not smart enough to debug it.”

—Brian Kernighan, co-author of The C Programming Language

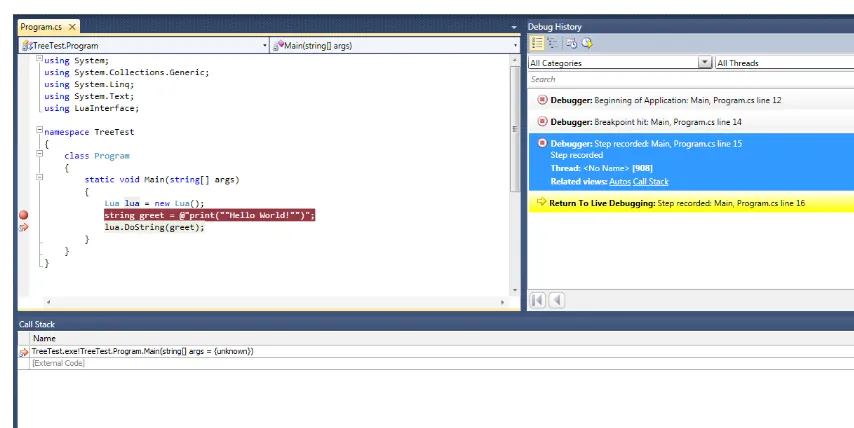

With historical debugging enabled, a debug history window opens to the right of the code panel when you run the application (Figure 1–8). Setting breakpoints allows you to drill deeper into the state of the application at each step. The Autos window and call stack are available as links, as well as

Figure 1–8. Historical debugging offers a step-by-step view of program execution.

■Note If you’re curious, the code in Figure 1–8 is using LuaInterface, available on Google Code at

http://code.google.com/p/luainterface/. Lua is a very popular (and free) scripting language that has gained a lot of ground with developers in recent years.

Improved JavaScript IntelliSense

Figure 1–9. JavaScript IntelliSense is fast and accurate.

jQuery Support

Not only did traditional JavaScript IntelliSense improve, but Microsoft has added full support for jQuery in its IntelliSense. jQuery is a freely available JavaScript library created by John Resig that has become quite powerful and popular in the developer community for its simplicity, ease of use, and cross-browser effectiveness. There is also a significant plug-in community as users find new and inventive ways to add some really startling client-side scripting elements to their applications via the jQuery environment.

■Note How popular is jQuery? Well, ask Google, Digg, Mozilla, Dell, WordPress, Netflix, Bank of America, Major League Baseball, and many other big-name companies and organizations. They all make use of it on their production sites, and you can find many more supporters on the jQuery home page.

Compare the code in Listing 1–15 and Listing 1–16. The first demonstrates a simple JavaScript class change by locating an element with an ID of foo and using the setAttribute() method to modify the class attribute.

Listing 1–15. JavaScript Method of Locating an Element and Changing Its Class

<script type="text/javascript">

var element = document.getElementById('foo'); element.setAttribute('class', 'red');

Now take a look at how jQuery performs that task in a concise, clear manner.

Listing 1–16. jQuery Method of Performing the Same Task

<script type="text/javascript"> $('#foo').setClass('red'); </script>

jQuery is really quite powerful in terms of the selection syntax it exposes to developers; consider that you want to find the third paragraph tag that has a class of storyText. jQuery makes the task trivially simple (Listing 1–17).

Listing 1–17. More Sophisticated Object Location Within the DOM

<script type="text/javascript">

$('p.storyText:eq(2)').setClass('red'); // the position is a zero-based lookup </script>

■Note DOM is short for document object model, and it’s a hierarchy tree of controls within any given web page. Navigating the DOM permits some rather sophisticated client-side modifications to be performed in your applications, and jQuery certainly makes elements conveniently accessible.

The library supports a variety of selectors; you can find elements by position in the page, ID, class, and so on. We’ll look at creative ways to use jQuery to enhance our public-facing user experience later.

■Tip Always consider the concept of graceful degradation when designing web applications where JavaScript is involved. Graceful degradation means that users with the most advanced or capable browsers can and should be presented with a pleasant and enhanced user experience, but users without such capabilities should be in any way restricted from using the site to its fullest. Basically, the bells and whistles can fall by the wayside so long as your app is functional. A user with JavaScript disabled is not going to find your accordion-style jQuery-animated navigation bar all that useful if it doesn’t function with JavaScript disabled.

jQuery is now included by default when creating new web sites in Visual Studio 2010 and consists of a handful of .js files in the project solution. It is also capable of providing consistent client-side

experiences in Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari, Opera, and Chrome. The jQuery site

Building a CMS

Now that we have a better sense of what’s new in the toolbox, it’s time to consider what to build with it. For the purposes of this book, we’ll be building a content management system (CMS) from the ground up.

The CMS detailed throughout this book is in fact a true production system used to serve tens of millions of pages per day. It was built for this book as an example of real-world application development, but also to fulfill business requirements learned over the life cycle of a previous CMS and deployed to a public-facing environment. As such, when examining the code, you will be working with an enterprise application that has been proven under a heavy load, providing high availability and a scalable architecture.

Because the CMS is a large application, it’s not possible for me to cover and document every single line of it in this book. However, I have applied XML comments to every method and class in the system, and the overarching concepts of the system are covered in entirety in this book. So although I may not cover the specific function of every line in methods A, B, and C, I will certainly cover the motivation behind the creation of the code, and I believe the internal design patterns will be very clear. I highly recommend that you download the CMS from the Apress site and work with it as you progress through the book.

CMS Functional Requirements

Although I wouldn’t go so far as to say we should define a complete design document, we should cover some ground on the requirements that the CMS is meant to fulfill. These are the core requirements:

• The system must support multiple sites.

• An administrative site must support end-to-end content creation (templates, pages, and styles).

• Whenever possible, the system should implement best practices (SEO, web standards, and so on).

• Scalability and availability should be primary concerns at all levels.

• Maintenance after deployment should be made as easy as possible (extensibility, plug-ins, and so on).

• Syndication, canonical links, RSS feeds, news, and so on, are necessary.

■Tip Canonical links are custom links that can be inserted into the head tag of an HTML page that allow search engines to determine the preferred location of a piece of content. For more information, see Chapter 9, which focuses on search engine optimization.

A lot of technical considerations go into creating a complete content management system; put simply, it’s a very difficult task. This difficulty and technical breadth make it an excellent choice for learning a new framework and how to apply powerful new languages. To successfully serve tens of millions of pages daily, there are some aspects of .NET that out of the box you may find simply don’t perform under such a load.

highlight issues such as this as we work through the CMS, as well as solutions that have produced results in the actual production system.

We’ll take advantage of power-user elements wherever possible; one example is via RSS feeds. It’s common to create pages or user controls that output RSS feeds to users, but at the penalty of all the overhead of the complete page life cycle. We can use a generic handler instead, effectively simplifying the entire process and making the application more responsive. The framework (and ASP.NET in particular) does a great job of leaving the implementation choices up to the developer, but a lot of developers haven’t made full use of these options. We’ll cover many ways to keep the CMS speedy in the face of your users.

Creating the Application Framework

Let’s set up some components of the application; the first thing I like to do when creating an application is define an overall solution that will house the individual projects within. I frequently keep most of my application’s code in separate class libraries so that my web projects are as lean as possible.

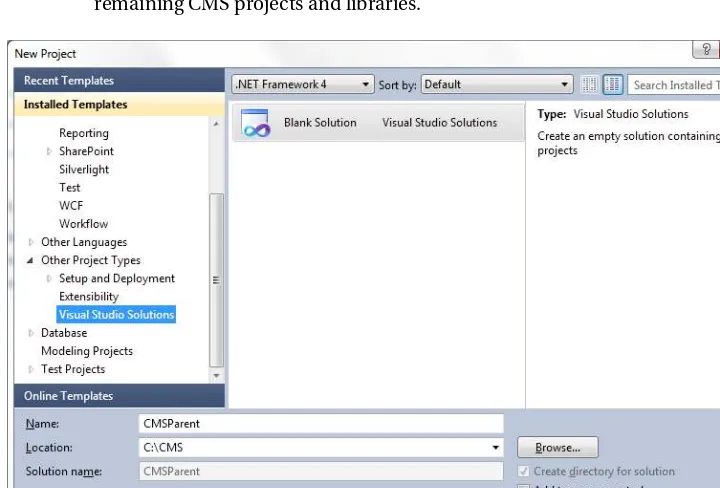

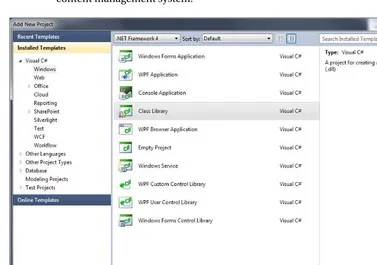

1. Create a new project in Visual Studio; select Blank Solution from Other Project Types Visual Studio Solutions. Name the solution CMSParent, and click OK (see Figure 1–10). This solution will be used as a common location for the remaining CMS projects and libraries.

2. Right-click the CMSParent solution in the Solution Explorer, and click Add New Project. Select Class Library from Visual C# Windows, and name it Business (see Figure 1–11). This class library will contain the business logic for our content management system.

Figure 1–11. Adding the business library

3. Repeat step 2 to create the CommonLibrary and Data class libraries.

CommonLibrary will house classes and interfaces that are common to multiple tiers of the application, and Data will be focused on communicating with SQL Server and persisting data.

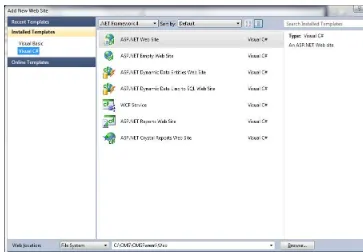

Figure 1–12. Adding the web site

5. Right-click the Web project, and click Set as StartUp Project. Your IDE should now look like Figure 1–13.

■Tip Throughout the book, I’ll assume that you’ve created your application at C:\CMS. Feel free to change the location if you prefer, but remember as you read that I’m placing things at this location.

Summary

■ ■ ■

CMS Architecture and Development

“Low-level programming is good for the programmer’s soul.”

—John Carmack

I think when id Software’s programming front man made this comment, he wasn’t referring to n-tier architecture and component-based development. That said, for a .NET developer working in a web environment, these concepts are sufficiently low-level enough to be the chicken soup he prescribed.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of building software primarily using the WYSIWYG editor and the drag-and-drop components that .NET provides. The limitation is twofold: first, large-scale design tends to fall by the wayside when compared to the ease of use of these prebuilt components. Second, there typically is an unusually large amount of code and functionality present in the presentation areas of the application that really belongs elsewhere.

In this chapter, we’ll take a look at the concepts of n-tier architecture and component-based development and begin work on the public side of our application. First we need to discuss the choice to build a CMS and why .NET is an excellent platform for its development.

Motivations for Building a CMS

There are plenty of content management systems on the market: Joomla!, Django, Umbraco, Drupal, and DotNetNuke are just some of the systems that spring to mind immediately. Many content management systems are free, some cost a pretty penny. Why even bother reinventing the wheel when so many off-the-shelf solutions exist?

The crux of the issue hinges on two points:

• First, the organization for which the system described in this book was created had very specific business requirements that were a direct by-product of the limitations that existed in the system it had been operating with previously.

• Second, as an instructional or demonstrational tool, a content management system touches on an expansive array of subjects and technologies. In short, it’s a pretty useful learning tool, and it solves some real-world problems that international organizations have to consider.

make them unique. Some focus heavily on providing content in XML form that is styled via XSLT; some focus on their extensibility model and ensuring that their plug-in capabilities are robust.

In the case of this book, the focus is heavily on building a system that can be expanded via plug-ins and that requires little to no modification of the core framework. For example, if I want to create a new component that displays advertisements on the right side of a page, I don’t want to have to modify the CMS itself; the system should be fairly unaware of what specifically is running on a page and instead focus on the primary task of delivering content. We should be able to create our advertising module, place it in a convenient location, and have the system simply pick up its availability and use it when appropriate.

The CMS we will build together is not meant to be a replacement for Drupal or to oust DotNetNuke in some fashion. It is simply a demonstration of what has worked in production for a real organization on a day-to-day basis, as well as how new technology from Microsoft makes the job easier than it has been in the past. The code is available to you to modify, use, and reconfigure as you see fit without restriction from me.

Motivations for Using .NET

The other big question mark is (aside from the fact that I am a .NET developer by day) why does .NET make an attractive technology platform for building a content management system?

At a high level, the .NET Framework provides a great deal of features that make developing such a system fairly straightforward. The framework has built-in mechanisms for authorization and

authentication, caching, rich server controls, and database access, just to name a few. Beyond the core framework, there are powerful languages such as C# and IronPython, tools like MEF, and the key fact that .NET is well-tested and known to be stable as a production system for some very large

organizations. Having a mature platform that can be relied upon to perform at the level necessary to handle massive amounts of traffic is critical to the success of such a project, and .NET shines in each area. It’s obviously feasible to build the same type of system in any number of other languages, but the .NET Framework makes things both convenient and (in many cases) easy.

Application Architecture

We know why we’re building a CMS, and we know why we’re using .NET to do it. Now we need to discuss the architecture of the application. We touched on the general concept of n-tier development in Chapter 1 when we discussed the architecture patterns Controller and Model-View-Presenter. Technically speaking, these patterns are three-tier; each contains three distinct elements with a unique set of responsibilities.

■Tip A tier denotes a physical separation, while a layer denotes a logical or abstract separation.

It is possible to have a one-tier architecture or a 100-tier architecture if desired. The most common separation is typically three-tier, and in fact when most people discuss n-tier architecture, the

Figure 2–1. A typical n-tier architecture separation of responsibility