Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 23:03

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Dichotomies in Teaching, Application, and Ethics

Joyce T. Heames & Robert W. Service

To cite this article: Joyce T. Heames & Robert W. Service (2003) Dichotomies in

Teaching, Application, and Ethics, Journal of Education for Business, 79:2, 118-122, DOI: 10.1080/08832320309599099

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320309599099

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 17

View related articles

Dichotomies in Teaching,

Application, and Ethics

JOYCE

T. HEAMES

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

University

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Mississippi

Oxford, Mississippi

ROBERT

W. SERVICE

Samford University

Birmingham, Alabama

n attempting to research and teach

I

business, we have found many star- tling dichotomies that seem to permeate both teaching and industry practice- differences between the way things are and the way most people think they should be. For instance, business educa- tion today emphasizes facts, skills, data, and a teacher-centered classroom, where- as most students would prefer an empha- sis on emotional intelligence, the sharing of information, and student-centered learning. Business education and practice are perhaps more prone to such paradox- es today than in the past for a variety of reasons: the perceived need for a scientif- ic answer for everything, the desire for a pill to cure all ills, the need for instant gratification, the growing number of stakeholders that share organizational concerns, the need to protect oneself and the organization from legal problems, the desire for a to-do list, and a preference for the measurable versus the significant. The development of any solution should start with kaleidoscope think- ing; most often when something seems impossible from a certain point of view, it is easier to accomplish with another viewpoint (Hesselbein, Gold-smith,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Somerville, 2002). In thisarticle, we seek to clarify how that new world view might be adopted, and, indeed, why it must be. Thus, we began with the following research question:

ABSTRACT. In this article, the authors propose a move from the old control model of teaching, managing, and leading based on stability and

power to a new enterprise model based

on speed and constant self-innovation. They hope to promote the practice of a rapid incremental innovation strategy

that produces practitioners and educa- tors dedicated to continuous improve- ment and ethical behavior. Specifical- ly, their aim is to help (a) improve undergraduate and graduate business programs while stressing ethics and

values; (b) provide a forum for thought about how to teach using a

student-centered, discussion-based approach, often called case teaching

or problem-based learning; (c) provide information to organizational entities

for use in changing or establishing training for and evaluation of excel- lence; and (d) improve organizations by supplying them with better leaders, managers, and teachers for the future.

What can academicians and practition- ers do differently in teaching and prac- ticing to provide more prepared and more ethical leaders?

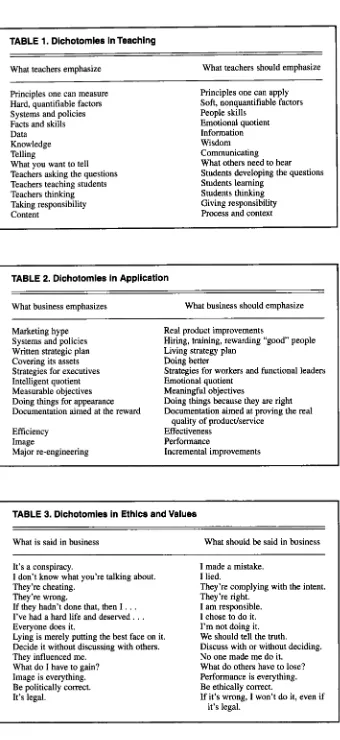

When Tables 1, 2, and 3 were pre-

sented to more than 150 undergraduate students, there was overwhelming sup- port for the conclusion that the left-hand column of each figure represents reality, or life as it really is, whereas the right- hand side represents how things should be. What seems to be an inevitable trend is that most things are indeed shifting more to the left side of the dichotomies

depicted. Teachers must recognize this shift and work to move thinking, teach- ing, and application back toward the concepts represented on the right side of the figures. We hope that the dichoto- mies shown in the tables can help guide thinking toward that shift.

Dichotomies in Teaching

It is very daunting to think about how academicians and practitioners can help prepare future corporate leaders to be better ethical managers and leaders. As we consider recent ethical lapses in cor- porate America, we may want to blame, in part, laws, tax codes, and accounting regulations that are difficult to interpret, accreditation entities that prefer docu- mentation to reality, and even human greed and laziness. Although those fac- tors do share a lot of the blame, acade- micians must also look to both them- selves and their students. Without a doubt, when academicians expect cer- tain behavior, they get it. However, there is little to be gained by identifying the villains or casting blame. Teaching excellence requires concentrating on solutions, not problems (Jackson &

McKergow, 2002).

The first step toward change in teach- ing is to move from teacher-centered responsibility and thinking to student- centered learning, from rote memory to

11.8

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education for BusinesszyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TABLE 1. Dichotomies In Teaching

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

What teachers emphasize What teachers should emphasize

Principles one can measure Hard, quantifiable factors Systems and policies Facts and skills Data

Knowledge Telling

What you want to tell

Teachers asking the questions Teachers teaching students Teachers thinking

Taking responsibility Content

Principles one can apply Soft, nonquantifiable factors People skills

Emotional quotient Information Wisdom Communicating What others need to hear Students developing the questions Students learning

[image:3.612.49.389.11.751.2]Students thinking Giving responsibility Process and context

TABLE 2. Dichotomies in Application

What business emphasizes What business should emphasize

Marketing hype Systems and policies Written strategic plan Covering its assets Strategies for executives Intelligent quotient Measurable objectives Doing things for appearance Documentation aimed at the reward

Efficiency Image

Major re-engineering

Real product improvements

Hiring, training, rewarding “good” people Living strategy plan

Doing better

Strategies for workers and functional leaders Emotional quotient

Meaningful objectives

Doing things because they are right Documentation aimed at proving the real

Effectiveness Performance

Incremental improvements quality of producdservice

TABLE 3. Dichotomies in Ethics and Values

What is said in business What should be said in business

It’s a conspiracy.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I don’t know what you’re talking about. They’re cheating.

They’re wrong.

If they hadn’t done that, then I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

..

.

I’ve had a hard life and deserved.

. .

Everyone does it.Lying is merely putting the best face on it. Decide it without discussing with others. They influenced me.

What do I have to gain? Image is everything. Be politically correct. It’s legal.

I made a mistake.

I lied.

They’re complying with the intent. They’re right.

I am responsible.

I chose to do it. I’m not doing it. We should tell the truth.

Discuss with or without deciding.

No one made me do it.

What do others have to lose? Performance is everything. Be ethically correct.

If it’s wrong, I won’t do it, even if it’s legal.

application, from answering questions to developing questions, and from taking responsibility to giving responsibility. Problem-based learning is only effective when students learn how to identify and define problems, as well as how to ana- lyze and reject possible solutions. In commerce today, there are many who can solve problems but few who can define the real problems that need to be solved. Management researchers are social scientists who favor the measur- able and the quantifiable, but the soft, hard-to-measure aspects are the critical issues. Indeed, faculty members in man- agement science have “killed” the very thing they are trying to measure.

Moreover, “[iln attempting to deal with the observable and measurable aspects of leader[-teacher] behavior, and perhaps to simplify for normative pur- poses, leader[-teacher] research has focused on a narrow set of [vari- ables].

. . .

Again, in attempting to dissect a living phenomenon, the skeleton may be revealed while the specimen dies” (Westly & Mintzberg, 1991, p. 40). When a professor asked a college junior in an Introduction to Management course what he expected to get out of the class,the student said, “I expect

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

you to teachme how to be a manager.” The instructor

replied, “Wow, are you going to be disap- pointed!” Years later the student, now a very successful manager, said, “I now know what you meant!” First and fore- most, we must teach students to figure problems out for themselves, not to fol- low prescribed formulas.

Leadership Versus Management

Management educators are in the busi- ness of teaching manipulation in one form or another. We teach emotional quo- tient and soft skills aimed at motivating others and moving everyone in the same direction with a unified sense of pur- pose: This is management. Management becomes leadership when a leap of faith on the part of the followers is required to

move them in the desired direction. Man- agement is logical; leadership goes beyond logic. Academicians must become skilled at teaching management and leadership with ethics and values in such a way that the practice becomes sys- tematized, sustainable, and transferable.

NovembedDecember 2003 1 19

[image:3.612.52.389.54.275.2]Dichotomies in Practice

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

There are two basic ways to promote anything, whether it be problems, orga- nizations, products, or politics. One way is to use hype to manipulate the price, the quality perception, or whatever. The second way is simply to improve what one is trying to promote. Recently, it seems that there has been more manipu- lation of perceptions than actual improvements. Why? Simply enough, it is usually quicker to change the image of the product than the product itself. Perhaps hype should be the preferred solution if the goal is a high year-end stock price or a personal annual promo- tion. But if the goal is long-term sur- vival and sustainable success for the preponderance of stakeholders, the final answer must be basic improvements of products and services, not hype.

We need to consider rewards, thought, and actions within a long-term vision. This has never been truer than

with the teaching of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

real value creationthat is accomplished in an ethical man- ner. When it comes to corporate behav- ior, what matters is what leaders and managers do when no one is watching. Similarly, in teaching, it matters little whether we have taught hundreds of theories and principles. More important, we must show that our students can suc- cessfully apply something that they have learned through the experiences that we, as their teachers, have helped provide. This shift in both the teaching and practice of management and leader- ship is a necessity for the long-term excellence and survival of the free enterprise system.

With that said, it seems clear that there must be an emphasis on teaching ethical leadership, not just management. We need to get back to basics and tem- per political correctness rather than con- stantly worrying about what is being said or who is being offended. The fol- lowing true story exemplifies this: In the early 1980s, a speaker who came to a small Baptist university started his speech by saying, “There are millions of kids starving to death even as I speak, and no one here gives a shit.” There was a collective gasp. The speaker contin- ued, “And you know what’s even sad- der? It’s the fact that most of you are

more worried about the fact that I said shit than the fact that millions of kids are starving.” Too many areas of educa- tion-especially diversity, race rela- tions, ethics, and values-are reaching that point of absurdity. The dichotomies

presented in Tables 2 and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

3 should act asstarting points for thinking about what types of learning, leading, and manag- ing we should strive for and how ethics can be slanted by language.

So how can we improve things? That is a difficult question, for if we simply prescribe a plan then we have come full circle. Continuous change, willingness to experiment, and diligent expansion of knowledge requires generating, refuting, and applying many varied approaches to practicing, learning, and teaching. I refer to this strategy as innovation through rapid incrementalism, and it works in

teaching and applying ethical business for excellence.

Teaching Techniques That Work for Us

Now, after disavowing all formulas and rules, we suggest a framework for successful teaching in the form of a series of loose guidelines. The frame- work rests on a foundation of caring, values, and fun. However, one must remember that the only real rule is that there are no rules beyond creating a teaching environment that embodies honesty, respect, and values.

Guideline 1: Class Objectives

Before each class, list a series of broad learning objectives on the board. Then start by having students decide how to discuss the objectives. For exam- ple, in an Introduction to Management course, the professor listed “manage- ment in the context of organizations” as a first objective. Then, the students dis- cussed the importance of organizations and management, developed definitions of the terms, and fleshed out how the two are connected. Finally, each student was asked to produce an example of an organization with which he or she was associated and describe how the organi- zation is managed and fits into varied managerial or cultural contexts. By shar- ing concrete examples, students clarified

their understandings, which made them more likely to think as leaders.

Guideline 2: Fit the Students

Direct class discussions so that they fit the students’ interests yet are related to class objectives. Lecturing inhibits free and creative thought and should be used sparingly. If necessary, give an executive summary in the last 15 min- utes of class to bring the discussion to a more natural conclusion or to ensure that all students are comfortable with the handling of the objectives.

Guideline 3: Reflect on Relationships

A major problem in management education occurs when technical com- petence is stressed over relationships

and emotional quotient (Hunt

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Scan-lon, 1999; Krass, 1998; Willingham, 1997). Often, students learn the most important lessons outside the class- room. A student’s job is to relate real- life experiences to what is learned in class, or to apply knowledge gleaned from class, the text, or other research to situations in real life. To stress this crit- ical issue, ask students how they can better manage their relationship with a professor and how they can apply that knowledge to other real-life relation- ships, such as those with parents, a girl- or boyfriend, or an employer. When the student can apply business concepts to life in multiple arenas, whether the football team, the sorority house, or a job, then they have learned a life lesson.

Guideline 4: Emphasize the Unorthodox

Handle each class differently and use many unconventional techniques each term. A dynamic environment with a blend of styles and interrelated methods works best for most students. The fol- lowing are just a few of the ideas that we have used recently:

Tell the students that you want them to teach you about the assignment. Use transparencies, but sparingly. Hand out copies of timely articles and give the students time to read and discuss them.

120 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinessRole-play situations.

Discuss whatever topic you and the students choose, no matter how off the wall it may seem. Students love to dis- cuss abortion, discrimination, homosex- uality, politics, religion, life, and so on.

Tell jokes and use stories to enter- tain and, most important, to illustrate principles.

Use a computer to aid a presenta- tion.

Invite speakers of all skill levels to discuss a variety of topics. Ask a CEO, a middle manager, a blue-collar worker, or a recent graduate, for example.

Divide your class into groups and have them derive how many square feet are in a given state or how many square yards of turf it would take to replace all

the fields in the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

NFL.

These exercisesare similar to questions that many orga- nizations now ask in interviews to see if potential hires can reason.

Facilitate some case studies. Always ask students to discuss and explain the what, when, why, and how of the situation.

Have the students complete the exercises at the end of a chapter in a book.

Have students use name cards and make them learn each other’s names. Make sure you know all of them by name as well.

Check the roll without calling it, and when students walk in after missing a class, say, “Jan, we missed you last time. Would you please start the class for us?’

Ask all late students a question as soon as they arrive.

Ask students to address each other by name and discuss or debate among themselves before they reach a conclu- sion.

Have students evaluate each other

and themselves. Then give students gen-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

eral feedback on how they are perceived

by their peers as well as constructive criticism on how you perceive them. Students who desire to become good business leaders must become accus- tomed to giving and receiving feedback about perceptions and performance.

Make yourself a list of activities that you will commit to each semester. For example, one semester you might decide to give out and discuss sum-

maries of 10 new business or manage- ment books, five academic journal arti- cles, 10 current press articles, three pleasure books, and five lists of “inter- esting stuff.”

Try to avoid using a standard text. The best complement is, “This is like a book I would read anyway.” Give each student a book other than the text and make him or her responsible for work- ing it into the discussions and providing everyone with a one-page summary of the book. At other times have them select the additional text themselves.

Require each student to do at least one presentation during the semester. In a large class with 50 students or so, make them stick to a 5-minute presenta- tion. Speaking in front of a group is one of the most critical skills in business, and the ability to make short but effec- tive presentations is a skill for which many employers are willing to pay top dollar. Just think, if all relatively small classes required a presentation, students will have given 25 or more presenta- tions by graduation. Discussions with hundreds of working MBA students reveal that most wished that they had been required to make more presenta- tions in undergraduate classes.

Be active. Call yourself a change agent and become one. Act enthusiastic - n e v e r stand still for long, literally or figuratively. Go out of your way to run

into students and speak to them in non- classroom settings, such as at sporting events or student plays. Get to class early and be the official greeter. If you think you will have a hard time adjust- ing to these changes, think about what we ask students to do when they must adjust to each of our differences.

These varied approaches provide stu- dents practice in dealing with the myri- ad methods, situations, and people that they will encounter in the world of busi- ness. Follow these suggestions initially, and then develop four or five new ideas each term. Then you will be implement- ing a rapid incremental innovation strategy in your teaching.

Guideline 5: Expand Opportunities f o r Critical Assessment

Multiple-choice exams should not be used, except perhaps in classes of more

than 100 students. Instead, require four or five written assignments each term. Take-home exams are a more thought- provoking comprehensive review, stress- ing real-life learning versus measure- ment, particularly if they ask questions about the texts, handouts, and discus- sions, as well as questions that have not been covered and are not in the text but can be found in the library or on the Internet. A good conclusion to a take- home exam is to have students discuss the ethics of getting help on the exam. In life neither managers nor teachers are asked to choose a, b, c, or d , and even

more seldom are they told that the cor- rect response was covered in class or in an assigned book. Ask for judgment, analysis, critical thinking, and concept application.

Guideline 6: Use Technology to Add Value

High-, low-, or no-technology inno- vations are all critical to continued suc- cess. However, technology in and of itself is of no use. If crummy informa- tion is presented with a dull attitude, all the color, figures, and bells and whistles in the world will not really help. Tech- nology does not beat spontaneous ex- amples given by students about things that they understand. Technology should not replace thinking. Do not give the responsibility for good teaching to technology. The most important innova- tions-including newspaper advertis- ing, management as a field of study, credit, life insurance, and so on-are often not technology based. Avoid the use of technology as a crutch or a pseu- doscientific cure-all to avoid work and

preparation.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Defining Success

Teachers must motivate and encour- age success, not put up hurdles to it. A college professor was overheard saying, “I’m really going to blow their minds today and put them on the hot seat.” Later, after he graded his tests, he bragged, “Boy, I killed them; the high-

est grade on my last test was a

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

42.” Hethought that teaching was fun if he was “messing with the students.” But it is doubtful that his students shared that

NovembedDecember 2003 121

opinion. The definition of success needs to come from the students, not from the professor. Remember, if students enjoy success in a positive environment, they

are more likely to be open to learning.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Evaluation and Adjustments

A common fallacy is that good teaching cannot be measured. As edu- cators, we talk with MBA students about how Bill Gates could do a better job; why Jobs, Sculley, and Spindler failed at Apple; what Akers did wrong at IBM; what Gerstner can do to fix it; and so forth. Then, we have the nerve to say that we cannot measure good teaching. Tell any top executive that you cannot measure what you are paid to do and you will be on the street, and rightfully so.

Teachers can and must be measured. Think about your department, school, and university and you will know immediately who the good teachers are; if you do not, you can bet that the current students and recent graduates do. Teaching effectiveness is being measured and talked about every- where. Use, but do not depend on, the standardized evaluations at the end of the term. Develop some new and inno- vative ones and administer them at least three times a semester. Ask stu- dents to rate the effectiveness of texts, other materials, exercises, classmates’ contributions, and your teaching. Use a 10-point rating scale, because students

know

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

0s and 10s when they see them.Also, always leave an open-ended

comment section, or distribute 3 x

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5cards for comments. Whatever you do, use the evaluations. Read and sort them and then address the students’ concerns in class. Tell them what you will change, what you do not want to change, and why.

You also could use an adaptation of the “new manager assimilation” session that many businesses currently use. Do this by inviting a colleague who is well

liked by students to facilitate a discus- sion with one of your classes without you. Have the professor or fellow train-

er go in with an open mind

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

and

seekfeedback on how you teach, how much you seem to care, how well you know the material, how much you facilitate student learning, how effectively you use your talents, what your students like and do not like, what they would like to change, and so on.

In business school classes, profes- sors are there to help students move into the business world. Students’ effectiveness in that world is strongly suggestive of our effectiveness in preparing them for it. That is the mea- sure of teaching excellence.

Implications

The motto of a truly innovative leader or teacher should be, “If it ain’t broke, break it and start over.” The chief impli- cation that we want to avoid in this arti- cle is that we simply are espousing a method. Our only method is no method, although we have presented some very loose guidelines and dichotomies designed to stimulate thought about the many and varied choices that teachers have. The only rules are “show respect” and “just try it.”

We hope to provoke some debate and cause teachers to realize that there is no one best method-and if there were, it would quickly be leapfrogged. For as with excellence in management, excel- lence in business school teaching requires a willingness to fail. Unfortu- nately, many will ignore the necessity of being innovative because they fear fail- ure or lack confidence. Teachers may be afraid of appearing to know less than their students.

Summary

Good ethical, innovative teaching (leading/managing) is built on several principles: (a) using rapid incremental

innovation; (b) empowering others; (c) emphasizing thinking over memorizing; (d) applying knowledge; (e) fitting one’s teaching to one’s own style and that of one’s partners in work and learn-

ing;

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(0

balancing the teaching dichot-omies of Table 1 and the application dichotomies of Table 2; (g) aiming for the “What Should Be Said” side of the ethics dichotomies shown in Table 3; (h) reflecting on a composite of one’s learn- ing in class and in one’s life; (i) gener- alizing from similar situations;

u)

understanding the importance of context and process; and(k)

understanding the dichotomies in leading, managing, teaching, and ethics.To improve, we must accept the past, succeed in the present, but remain poised for the opportunities of the future. More- over, we must understand motives and realities versus excuses. For life is really a test; if it were not, it would come with more exact directions. “Remember, in [teaching-managing-leading] as in any other endeavor, there is talent, there is ingenuity, and there is knowledge. But when all is said and done, what [teach- ing-managing-leading] requires is hard, focused, purposeful work. If diligence, persistence, and commitment are lack- ing, talent, ingenuity, and knowledge are of no avail” (Drucker, 1991, p. 17).

REFERENCES

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Drucker, P. F. (1991). In J. Henry & D. Walker

(Eds.),

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Managing innovation. London: Sage.Hesselbein, F., Goldsmith, M., & Somerville, I. (Eds.). (2002). Leading for innovation and organizational results. New York: Jossey-Bass. Hunt, C. W., & Scanlon, S. A. (Eds.). (1999). Nav-

igating your career. New York Wiley. Jackson, P. 2.. & McKergow, M. (2002). The solu-

tions focus: The simple way to change. London: Nicholas Brealey.

Krass, P. (Ed.). (1998). The book

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of leadershipwisdom. New York: John Wiley.

Westly, F., & Mintzberg, H. (1991). In J. Henry &

D. Walker (Eds.), Managing innovation. Lon-

don: Sage.

Willingham, R. (1997). The people principle: A revolutionary redejnirion of leadership. New York: St. Martin’s.

122