www.elsevier.com / locate / econbase

Indeterminacy in a model with aggregate and sector-specific

externalities

a ,

*

bSharon Harrison

, Mark Weder

a

Department of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University, 3009 Broadway, New York, NY 10027, USA b

Department of Economics, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany Received 19 October 1999; accepted 25 May 2000

Abstract

We present a two sector dynamic general equilibrium model with both sector-specific and aggregate externalities. We find that including the aggregate effects allows for a trade-off between the sizes of the two types of externalities needed for indeterminacy. 2000 Elsevier Science S.A. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Sunspots; Indeterminacy; Production Externalities

JEL classification: E00; E32

1. Introduction

Recent years have witnessed the formulation of dynamic general equilibrium models with sunspot

1

equilibria and self-fulfilling prophecies. In such models, the resulting possibility of a continuum of equilibria is the consequence of some market imperfection. This market imperfection may come from increasing returns to scale in production, often driven by external effects. In this paper we present a two sector representative agent model with perfectly competitive markets and increasing returns to scale driven by externalities that come from both sector-specific and aggregate economic activity. The model is based on Benhabib and Farmer (1996), who find that small, empirically plausible

2

sector-specific external effects lead to indeterminacy. However, this is the first paper that examines the simultaneous presence of both sector-specific and aggregate externalities. We find that including

*Corresponding author. Tel.: 11-212-854-3333; fax:11-212-854-8947. E-mail address: [email protected] (S. Harrison).

1

These include: Benhabib and Farmer (1994, 1996); Benhabib and Nishimura (1998); Christiano and Harrison (1999); Farmer and Guo (1994); Harrison (1999); and Weder (1998, 2000).

2

See Basu and Fernald (1995, 1997) and Harrison (1998) for empirical evidence on returns to scale.

aggregate effects does not reduce the overall level of returns to scale needed for indeterminacy. Instead, it simply allows for a trade-off between the two types of external effects. In fact, it is the two sector model with sector-specific externalities alone that generates indeterminacy with the smallest departure from constant returns.

2. The model

2.1. The household problem

The representative agent maximizes the utility criterion

`

2rt

U5

E

slog Ct2cL etd dt, c.0, r.00

3

where C , L andt t r stand for consumption, labor, and the rate of pure time preference, respectively. We assume the capital accumulation technology

~

Kt5It2dK ,t d [(0, 1)

where I is the agent’s investment expenditures andt d denotes the rate of capital depreciation. Letting

w denote the wage rate, r the rental rate on capital, p the relative price of investment (witht t t

consumption as our numeraire), and denoting byLt the shadow value of wealth, the agent’s first-order conditions are

In addition, the agent must obey the usual transversality condition

2rt

lim e LtKt50 (4)

t→`

2.2. The firms’ problems

In the consumption sector, the firm maximizes profit subject to:

C a 12a

yt 5A k lt c,t c,t ,a[(0, 1)

3

where

C C

a 12a u a 12ag At5

s

K Lc,t c,td

s

K Lt td

Here kc,t and lc,t denote the capital and labor the firm devotes to production of the consumption good.

Kc,t and Lc,t are the economy-wide average capital and labor devoted to production of the consumption good, which are taken as given by the firm. Also taken as given are K and L , the economy-widet t

C C

averages of total capital and labor. The parametersu andg denote the sizes of the sector-specific and aggregate externalities, respectively. In the investment sector, the firm maximizes profit subject to:

Here the variables are defined as above, but for the investment sector. Given their goals of maximizing profits, firms hire capital and labor to satisfy:

C I C I

ayt ayt (12a)yt (12a)yt

]] ]] ]]] ]]]

rt5 k 5pt k and wt5 l 5pt l (5)

c,t I,t c,t I,t

Finally, throughout the paper, we assume that the following holds:

j j

Assumption. The level of increasing returns from all sources is such that a(11g 1u ),1, for

4

j5C, I.

2.3. Competitive equilibrium and dynamics

In competitive symmetric equilibrium, we have kc,t5Kc,t and lc,t5L . We define a perfectc,t

foresight equilibrium as follows.

Definition. A perfect foresight equilibrium is a set of sequences of capital, labor, the shadowvalue of wealth and an initial capital stock K(0).0 satisfying (1)–(5). In addition, the resource constraints

hold.

We derive local dynamics by Taylor approximating around the steady state, which boils down to the two-dimensional system:

~logLt logLt2logL

5J

F G F

~log Kt log Kt2log KG

4

where J is the 232 Jacobian. Recall that Lt is a non-predetermined variable and that K ist

predetermined. Hence, indeterminacy requires that both eigenvalues of J have negative real parts (i.e. a sink) which is equivalent to

Tr J,0,Det J (6)

Thus, neitherg noru appear in the Jacobian J. This result is reminiscent of Harrison (1999) and Weder (2000) who, however, examine sector-specific increasing returns only. By solving for the conditions for a negative trace and positive determinant, we are able to formulate Proposition 1.

2

Otherwise, indeterminacy results if and only if

2 I

a d2ad(12a)g I

]]]]]] ,2 u

r1(12a )d

5

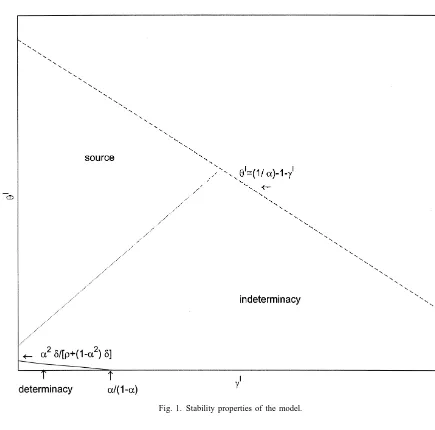

Fig. 1 summarizes the parameter space for the first case. The figure is drawn using the calibration suggested by Benhabib and Farmer (1996):a50.3,d50.1 andr50.05. Given our assumption, we study only the area underneath the dashed line. The negatively sloped line denotes the border of

I 2 2

determinacy and indeterminacy. At the y-intercept, u 5a d/(r1(12a )d). At the x-intercept,

I I I I

g 5a/(12a). We denote theseumin andgmin, respectively. Note thatuminis equal to the minimum

I

value needed for indeterminacy in the two sector model without aggregate externalities whilegmin is equal to the value of aggregate externalities above which indeterminacy results in the one-sector

6

version of the model. Simple algebra allows us to formulate Proposition 2.

I I

Proposition 2. The minimum scale economies that imply indeterminacy

s

gmin, umind

are such that5

The equivalent figure without the upper bound Tr J50 is not reproduced here. 6

Fig. 1. Stability properties of the model.

2

a d a

I ]]]]] ]]] I

umin; 2 ,(12a);gmin

r1(12a )d

for every parameter constellation sa, d, rd.

I I

For example, under the Benhabib and Farmer calibration,umin50.0638 andgmin50.4285. While the first value is within the range of empirical plausibility, the second is not. This result is not surprising, given previous work on both the one and two sector models. The presence of sector-specific externalities leads to reallocations of factors across sectors, and therefore movements in the return on capital, that are not at work when externalities are only aggregate.

Remark

This behavior can be understood as follows. Essentially, as we move down the negatively sloped line in Fig. 1, the model is changing from one with two sectors to one with only one sector. This allows for a trade-off between the two types of externalities. However, including aggregate effects does not reduce the overall level of returns to scale needed for indeterminacy. In fact, it is the two sector model with sector-specific externalities alone that generates indeterminacy at smallest departures from constant returns.

4. Conclusion

We have examined a two sector model with both sector-specific and aggregate externalities. It is the presence of these externalities, and specifically of those that come from the production of the investment good, that can lead to indeterminacy of equilibria. We find that including aggregate effects does not reduce the overall level of returns to scale needed for indeterminacy. Instead, it simply allows for a trade-off between the two types of spillovers. While this paper has shed some light on the types of external effects that are needed for indeterminacy in the two sector model, it still leaves open the question of whether allowing for both sector-specific and external effects has significant implications for the time series properties of the model. We hope to pursue this line of research in the near future.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jess Benhabib and Jang-Ting Guo for helpful discussions. This work was done while the second author was visiting Barnard College. Weder gratefully acknowledges financial support from a Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft research grant. This project was also supported by the Sonderforschungsbereich 373 ‘Quantifikation und Simulation wirtschaftlicher Prozesse’.

References

Basu, S., Fernald, J.G., 1995. Are apparent productive spillovers a figment of specification error? Journal of Monetary Economics 36, 165–188.

Basu, S., Fernald, J., 1997. Returns to scale in US production: estimates and implications. Journal of Political Economy 105, 249–283.

Benhabib, J., Farmer, R., 1994. Indeterminacy and increasing returns. Journal of Economic Theory 61, 19–41.

Benhabib, J., Nishimura, K., 1998. Indeterminacy and sunspots with constant returns to scale. Journal of Economic Theory 81, 58–96.

Christiano, L., Harrison, S., 1999. Chaos, sunspots and automatic stabilizers. Journal of Monetary Economics 44, 3–31. Farmer, R., Guo, J.-T., 1994. Real business cycles and the animal spirits hypothesis. Journal of Economic Theory 63, 42–73. Harrison, S., 1998. Evidence on the empirical plausibility of externalities and indeterminacy in a two sector model, Working

Paper 98-05, Barnard College.

Harrison, S., 1999. Indeterminacy in a model with sector specific externalities, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, in press.

Weder, M., 1998. Fickle consumers, durable goods and business cycles. Journal of Economic Theory 81, 37–57. Weder, M., 2000. Animal spirits, technology shocks and the business cycle. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 24,