Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 19:36

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Livelihood recovery in the wake of the tsunami in

Aceh

Craig Thorburn

To cite this article: Craig Thorburn (2009) Livelihood recovery in the wake of the tsunami in Aceh, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 45:1, 85-105, DOI: 10.1080/00074910902836171

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074910902836171

Published online: 26 Mar 2009.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 636

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/09/010085-21 © 2009 Craig Thorburn DOI: 10.1080/00074910902836171

LIVELIHOOD RECOVERY

IN THE WAKE OF THE TSUNAMI IN ACEH

Craig Thorburn*

Monash University, Melbourne

This article provides a brief overview of issues relating to livelihood recovery as-sistance and achievements in Aceh since the December 2004 tsunami. ‘Livelihood’ programs were intended to help tsunami-affected households quickly resume pro-ductive activities and return to ‘normal’ life. They formed an important compo-nent of the tsunami recovery portfolios of the Indonesian government and many international donors, distributing millions of dollars worth of equipment, cash and other forms of support to tsunami victims. This article queries the effectiveness and impact of some of these programs in Acehnese villages, particularly during the early phases of recovery. It is unlikely that an international response on the scale witnessed in Aceh over the last four years will occur again with future disasters. Nonetheless, the ‘livelihoods’ approach is probably here to stay, and many impor-tant lessons can be drawn from the Aceh experience.

INTRODUCTION

The Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami of 26 December 2004 and the subsequent reconstruction effort are events without precedent in human history. The tsunami devastated the lives and livelihoods of millions of people. Hundreds of agencies and thousands of people from countries all over the world have been involved in helping to rebuild shattered communities in the 14 countries affected by the tsu-nami. Billions of dollars have been committed, making this the largest post-disaster recovery and development endeavour undertaken in the developing world.

The Tsunami Evaluation Coalition’s Synthesis Report (Telford, Cosgrave and Houghton 2006) estimated that within the fi rst few weeks after the tragedy,

gov-ernment and private sources committed over $13.5 billion (for all affected coun-tries). This translates to an astonishing $7,100 for each of the 1.9 million people directly affected by the tsunami—many times more than for any previous dis-aster (as little as $3 per victim was provided for the 1998 fl oods in Bangladesh,

for example). This number was subsequently scaled back to roughly 60% of the

* Parts of this paper appeared in the report of the Aceh Community Assistance Research Project on post-tsunami recovery (Thorburn 2007), written by the author and published by the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) in December 2007. Permission by AusAID to reproduce sections of the report is gratefully acknowledged. AusAID does not guarantee the accuracy, reliability or completeness of any information contained in the mate-rial and accepts no legal liability whatsoever arising from any use of the matemate-rial. Users of the material should exercise their own skill and care with respect to their use of the material.

original fi gure as recovery agencies operating in tsunami-affected countries made

more accurate calculations of the cost of rebuilding. The Indonesian province of Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam (hereafter ‘Aceh’) was the region most severely affected by the tsunami and received the greatest portion of recovery assistance. The assistance fi gures for Aceh are roughly in line with the region-wide

num-bers. International donor and NGO commitments to recovery in Aceh (and the neighbouring Nias islands in the province of North Sumatra) amounted to $5.54 billion (World Bank 2008b), or roughly $3,350 for each surviving resident of the 80 sub-districts experiencing major or moderate tsunami damage. Contrast this with Aceh’s pre-tsunami per capita GDP of Rp 9.8 million, or approximately $1,090.1

In addition to international funding, between 2005 and 2009 the Indonesian gov-ernment allocated $2.23 billion) of its own funds to the recovery effort, increasing total tsunami recovery and reconstruction allocations for Aceh and Nias to $7.77 billion. The sheer volume of this aid—in combination with the ambitious dead-lines set for the recovery process—inevitably resulted in serious overlaps and redundancies, mis-targeting and hastily planned and implemented programs, and a large amount of money being squandered.

Four years into the recovery, tremendous strides have been made in the effort to ‘build [Aceh] back better’, to borrow the phrase, coined by Indonesian Presi-dent Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, that subsequently became the mantra of the Indonesian government’s Agency for the Rehabilitation and Reconstruction of the Region and Community of Aceh and Nias (Badan Pelaksana Rehabilitasi dan Rekonstruksi Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam dan Nias, or BRR). Scores of national and international relief and recovery organisations have engaged in the recovery effort.

Allowing people to resume productive activities and supporting the recovery of local and regional economies is a vital step in the transition from emergency relief to longer-term recovery. It forms one of the primary objectives of the Indo-nesian government’s master plan for the rehabilitation and reconstruction of Aceh and Nias.2 Many people in Aceh had been living in poverty before the tsunami;

thousands more were suddenly plunged into poverty. In Aceh, the security of lives, livelihoods, possessions and communities had already been shattered by 30 years of armed confl ict between the Indonesian military and the Free Aceh

Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, GAM). According to the government’s own statistics, in 2002 (the latest year for which fi gures were available), nearly half of

the population had no access to clean water, one in three children under the age of fi ve was under-nourished, and 38% of the population had no access to health

facilities (BPS 2004). And the situation was getting worse: between 1999 and 2002, the poverty rate in Aceh doubled, from just under 15% to nearly 30%.

Within just one year after the tsunami, Oxfam (2005) estimated that nearly half the people who had lost their jobs as a result of the disaster were again earning a

1 Even this fi gure is misleadingly high, because 40% of Aceh’s GDP in 2004 derived from oil and gas and related manufacturing. Proceeds and benefi ts from these sectors notori-ously did not fl ow to the people of Aceh, who suffered one of the highest poverty rates of any Indonesian province—28.4% in 2004, when the national fi gure was 16.7% (World Bank 2006).

2 See the BRR website, <http://www.e-aceh-nias.org/home/> (especially the agency’s mission statement at <http://www.e-aceh-nias.org/about_brr/profi le.aspx>).

living, and projected that their ranks would continue to grow over the following two to three years.

THE ACEH COMMUNITY ASSISTANCE RESEARCH PROJECT (ACARP)

The Aceh Community Assistance Research Project was a multi-donor supported qualitative social research project, aimed at identifying and better understanding the factors that supported or constrained recovery and redevelopment in com-munities in Aceh in the wake of the Boxing Day 2004 earthquake and tsunami. Field research was undertaken by a group of 27 Acehnese social researchers, led by a team of senior researchers from the provincial capital of Banda Aceh and from Jakarta and Australia. It took place over a three-month period between July and September 2006 in 18 tsunami-affected villages in the districts of Aceh Barat, Aceh Jaya and Aceh Besar.3

The objectives of ACARP were to identify key organic and external factors that have infl uenced the success of communities in rebuilding their lives; to study

the factors and conditions that contributed to the re-establishment and successful engagement of local community capabilities in the wake of major upheaval from natural disaster and confl ict; to document and analyse the interaction between

communities and external agencies in the reconstruction and recovery process, highlighting community perceptions of progress, constraints and the value of external assistance; and to train a group of Acehnese researchers in sound social research methods and build momentum for continuing social research initiatives and evaluative projects in Aceh.

Teams of three researchers spent a total of four weeks in nine ‘matched pairs’ of villages from sub-districts within the study districts. In each pair, one village was apparently recovering better than its counterpart, allowing for some com-parative analysis. The researchers accrued a large quantity of data, including 533 household questionnaires, 298 interview transcripts, 54 focus group discussion transcripts and 87 case studies and family histories. Research teams also prepared village profi le documents for each of the 18 villages, following a standard

for-mat. The project collected plans, reports and other forms of secondary data from donors, NGOs, national and provincial government agencies and the interna-tional and Indonesian media. The main part of the ACARP report focuses on vil-lage governance, particularly leadership, decision making and problem solving, transparency and accountability; women’s participation; and social capital.4 The

report also includes shorter sections on livelihoods and economic recovery and development and on housing and infrastructure.

This paper presents an overview of the ACARP report‘s fi ndings on livelihoods

and economic recovery. Following a brief discussion of early recovery, particularly the vital role played by ‘cash-for-work’ programs, the paper looks at the ubiqui-tous ‘livelihoods’ assistance programs, and how these are playing out in various sectors in the survey villages.

3 For a more detailed description of ACARP’s project structure and donor support, see appendix 1.

4 For a summary of ACARP’s fi ndings on village governance, see Thorburn (2008).

A caveat is in order. Although one of the primary objectives of the ACARP study was to document and analyse the effectiveness, impact and constraints of external assistance in supporting community and economic recovery, this proved extremely diffi cult. As with post-disaster situations everywhere, conditions in

post-tsunami Aceh posed formidable challenges to the conduct of systematic social research. Most donors and implementing agencies were exceedingly gener-ous with their time, knowledge and access to documents, but were often unable to provide specifi c information about approaches taken in particular villages. Data

on individual programs and projects available from the BRR RAN (Recovery Aceh–Nias) database5 and collected from donors were often either too general—

generic statements of organisational philosophy rather than specifi c accounts of

approaches taken in particular contexts—or too narrow and specifi

c—spread-sheets of numbers of items or amounts of funds distributed to numbers of benefi

-ciaries. As well, Acehnese communities are surely suffering from ‘survey fatigue’, some of their members having become rather jaded after answering the same questions from so many people so many times, only to see the survey teams drive off, leaving the communities not knowing whether their responses will yield any results that are of use to them.

Community members often fi nd it diffi cult to recall precisely who did what,

and when. There have been so many projects and programs, fi eld visits, promises

and plans, assessments and evaluations that they all begin to blend together in people’s memories. Villagers can generally name the housing provider in their village, and recall some relevant details about specifi c forms of livelihood

assist-ance they have received—such as how much was given by which organisations, whether in the form of a grant or a loan, and whether they ever saw the providers again. Beyond this, however, their recollection of the recovery begins to meld into a blurry mélange of twin-cabs and Land Cruisers, extension agents and trainers, foreigners with cameras and tape recorders, bulldozers and backhoes, tents and temporary bridges, and crates and containers of instant noodles, rice sacks and corrugated roofi ng sheet. Many of the fi ndings presented in the ACARP report

and in this paper are therefore necessarily of a general nature, combining anec-dotal evidence with the perceptions and opinions of aid providers, recipients and sundry government sources.

EARLY RECOVERY

An early technical report by the National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas) and the Consultative Group on Indonesia (CGI) outlined the frame-work for a tsunami recovery strategy and identifi ed a number of principles for

reviving the regional economy (Bappenas–CGI 2005; see also Kuncoro and Reso-sudarmo 2006: 24–7). During the rehabilitation phase—which the report authors envisioned proceeding from months 3 to 12—emphasis was on providing short-term employment opportunities to generate household income and to stimulate the rebuilding of the rural and small-scale infrastructure necessary for commerce

5 BRR RAN (Recovery Aceh–Nias) Database: List of Projects by Sector, viewed 3 October 2007 at <http://e-aceh-nias.org/upload/By%20Sector30102007020437.pdf>.

and the delivery of essential public services. Much of this took the form of cash-for-work (CFW) programs and other forms of short-term assistance.

Commendably, the recovery effort quickly alleviated most of the transient pov-erty and suffering that was created by the tsunami, and the transition from emer-gency relief to longer-term reconstruction was rapidly achieved. An important component of this achievement was the vital role played by various cash transfer assistance programs during the early recovery period. This included regular dis-tribution of basic sustenance (jaminan hidup, or jadup) cash transfers to displaced families to supplement in-kind distribution of rice, oil, noodles and tinned fi sh. As

many as 516,000 people were receiving jadup funds during the early months of the recovery. This much-needed assistance, coordinated by the Indonesian Depart-ment of Social Affairs, played an important role during the early months before NGO grants could be distributed (Adams and Winahyu 2006).

More central to this analysis, however, are the CFW programs implemented in nearly every village in the tsunami-affected parts of Aceh. A relatively recent innovation in post-disaster responses, CFW programs are considered easier to administer than food-for-work (FFW) programs, and can be less disruptive to local markets: they infuse cash into economies while leaving recipients to decide how to allocate it in light of their own spending and saving priorities, and they harness idle labour in circumstances where people are no longer able to partici-pate in their routine employment activities.6

CFW programs were initiated in Banda Aceh within two weeks of the tsunami, and soon spread to outlying areas, reaching their peak intensity during the fi rst

three to four months of 2005. By the end of 2005, all CFW programs had ceased in Aceh. Data on the numbers of participants and the amounts distributed are not available, but the vital role played by these programs is widely acknowledged. A study conducted by the international aid organisation Mercy Corps showed that CFW income made up 93% of total household income during the typical 3–4 month duration of CFW programs supported by that agency (Doocy et al. 2006).

Another important fi nding of the Mercy Corps study concerns the role that

CFW programs played in the restoration of community life and hope. Within fi ve

months of the tsunami, in almost every community where CFW was carried out, people were living in their villages in temporary or semi-permanent structures, and local traders were beginning to operate small kiosks and shops. CFW income was spent on fresh fi sh, fruit and other food items, cigarettes, snacks, fuel and

transport; it was used to augment savings, mainly in the form of gold, or invested

6 A common criticism of CFW programs is that they can exert infl ationary pressure on local economies. This is a somewhat spurious claim, as in many post-disaster situations in developing countries there effectively is no local economy in the immediate post-crisis period, and any large infusion of aid funds inevitably leads to some temporary localised infl ation. Aceh was no exception. However, the BRR and the United Nations Development Programme did a commendable job of curbing the infl ationary effect of CFW programs. They did this by establishing guidelines for all NGOs and donors providing CFW assist-ance, including capping daily CFW payments at a level comparable to the daily rate for un-skilled labour before the tsunami (Rp 50,000). For a detailed discussion of the effectiveness and relative merits of CFW assistance in post-disaster situations, see Adams and Winahyu (2006) and Doocy et al. (2006).

in small businesses. People also used CFW income to support revival of commu-nity religious or cultural events.

During the program’s heyday several agencies, led by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the BRR, took steps to maximise the posi-tive impact of CFW programs while minimising possible negaposi-tive impacts. These steps included attempts to standardise wages paid by different organisations at pre-tsunami wage rates (see footnote 6). Through trial and error, implement-ing agencies also came up with an appropriate supervisor-to-participant ratio to ensure the quality and effi ciency of work, and supported this with monitoring

through unannounced visits, to pinpoint problems and guarantee compliance with guidelines. Exit strategies included slowing CFW activities as the programs neared completion (for example, reducing the numbers of work days per week), and shifting to ‘output-based labour payments’ (OBLPs) organised on a ‘per-project’ basis (Doocy et al. 2006). The latter is viewed as a transitional strategy, between emergency relief and longer-term recovery programming. The OBLP system has the advantage of increasing community involvement in planning and management, and its more output-oriented character represents a further step toward resumption of normal community life.

When the ACARP research was carried out—some 18 months after the cessa-tion of CFW assistance programs—it was widely argued that CFW undermined the vaunted tradition of gotong royong mutual assistance. However, that view is not supported by evidence collected in the ACARP research.7

LIVELIHOODS AND LIVELIHOOD SUPPORT

The term ‘livelihoods’ has become commonplace in international aid parlance since the early 1990s, spearheaded by the writings of Robert Chambers (1987, 1995) and the adoption of the ‘Sustainable Livelihoods Framework’ as ‘a new departure in policy and practice’ (DFID 1999: 3). Chambers and Conway (1991: 1) describe livelihoods and sustainable livelihoods as follows:

A livelihood comprises people, their capabilities and their means of living, includ-ing food, income and assets. Tangible assets are resources and stores, and intangible assets are claims and access. A livelihood is environmentally sustainable when it maintains or enhances the local and global assets on which livelihoods depend, and has net benefi cial effects on other livelihoods. A livelihood is socially sustain-able [if it] can cope with and recover from stress and shocks, and provide for future generations.

In practice, most ‘livelihood’ programs consist of distributing ‘assets’ (equip-ment, capital, skills training) to poor households, while attempting to inculcate ‘participatory’ approaches to planning, targeting and decision-making processes. In spirit, these programs are held to be a signifi cant departure from old-style

eco-nomic or regional development approaches.

BRR RAN database estimates (see footnote 5) show that approximately 12% of all tsunami relief ($225 million of the $1.786 billion that had been expended by

7 For a detailed discussion of the relationship between CFW programs and gotong royong, see Thorburn (2007: section 4.1.5, ‘Social capital’).

September 2007) was devoted to rehabilitating and developing the productive sectors, primarily small and medium-scale enterprises, agriculture and livestock, and fi sheries—that is, ‘livelihoods’. According to BRR RAN data, economic

devel-opment programs account for 15% of funds allocated and 21% of disbursements in the 18 ACARP villages. This amounts to per capita allocations and disburse-ments (to September 2007) of $406 and $303, respectively, for economic develop-ment programs.8

The Bappenas–CGI technical report cited above (Bappenas–CGI 2005) empha-sised the need to restore productive assets as a vital step in the transition from emergency relief to longer-term recovery in Aceh. This includes rehabilitating

fi sheries infrastructure and facilities, providing boats and gear, and reviving fi sheries-related craftsmanship, as well as rehabilitating farms and providing

rel-evant tools, equipment and inputs. The report’s longer-term reconstruction phase strategy (months 12–36) stresses the importance of community-led reform to reha-bilitate fi sheries-related ecosystems and promote sustainable mari-culture. It also

advocates agricultural technology transfer, diversifi cation and commercialisation;

agribusiness development; and programs to provide small and medium-scale enterprises with training, consultancy, advisory services, marketing assistance, information, technology development and transfer, business linkage promotion and linkages to fi nance and fi nancial services.

What subsequently transpired was a deluge of ‘livelihood’ programs which, after temporary and permanent housing construction and provision of basic social services, were the facet of the recovery process most often encountered by households in tsunami-affected areas. The prevalence of ‘livelihood’ programs in Aceh is so pronounced that the term has made its way into the Acehnese lexicon, just like ‘gender’, ‘NGO’, ‘twin-cab’ and ‘cash-for-work’.

The ACARP survey contained three questions that sought to identify the aid programs considered to be ‘most benefi cial’; to be ‘least benefi cial and/or most

problematic’; and to have made ‘undelivered promises’.9 Refl ecting the diversity

of experiences, ‘housing’ led the list in relation to all three questions. Beyond hous-ing, 23% of the programs cited as most benefi cial provided economic

develop-ment assistance—primarily cash grants or loans for enterprise developdevelop-ment. Yet of the programs considered least benefi cial or most problematic, 20% of responses

were also in the economic development assistance category, with livestock and agriculture programs in particular generating many complaints. In response to the ‘undelivered promise’ question, 31% of respondents listed economic devel-opment assistance programs—primarily enterprise develdevel-opment funds or ‘other

fi nancial aid’.

8 The accuracy of these fi gures is somewhat suspect. There is considerable co-mingling of categories in the RAN database. Many of the economic development programs on the database also include infrastructure components, and vice-versa. Most integrated health care programs include enterprise development components. Cash-for-work is sometimes classifi ed as economic development, at other times as infrastructure. Many aid providers have been remiss in updating their information with the database managers. The actual fi gures are probably much higher.

9 These and other questions in the ACARP household survey questionnaire can be found in Thorburn (2007: appendix 2).

KEY LIVELIHOOD ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS IN THE SURVEY VILLAGES

Fisheries

Nearly all respondents who indicated that ‘most or all’ household consumption came from household members’ own production were from fi shing villages. Even

though only about half the households in the survey villages that had owned boats before the tsunami had new boats when the survey was conducted, fi

sher-ies appears to be the economic sector (other than construction) that has recovered best since the tsunami. This said, many respondents were critical of assistance received for fi sheries.

… the boats [received from BRR] were made from inferior materials, not like the ones we owned before. Already, most of those boats can’t be used, they’re broken. It’s the same with the nets, hooks and other equipment. Most people say they’re too big, don’t fi t with conditions here. Only the engines can be used. They never consulted with the fi shermen about the boats they were going to supply, just came and distributed them. Yes, it is true that some people who received aid sold it be-cause they couldn’t use it, then used the money to pay other expenses. (Interview PM-07)10

There are people whose profession is farming. But they were given boats. Not just one time they got a boat, but two times! (Interview PK-13)

Most of the aid we received isn’t appropriate for fi shermen here, like the boats and the engines. In the past, the old men used small boats, but we’ve been provided with these big boats and engines. We can’t even get them out to sea most of the time. It’s a lot worse because the estuary is so much shallower now since the tsunami. (Interview CC-01)

Obviously, it has not all been as haphazard as this. In the Aceh Jaya district, a number of villages have vibrant post-tsunami fi shing industries.

With the aid that’s been distributed through the Panglima Laot,11 IMC [Internation-al Medic[Internation-al Corps] came and consulted with the fi shermen fi rst, and then provided the boats. In fact, there was another NGO from France, Triangle, that helped people build their own boats. They also helped with the fi sh landing facility, and an offi ce, warehouse and meeting hall for the Panglima Laot. (Interview LL-15)

Three factors have contributed to the success of programs in Aceh Jaya. First, the donors consulted with recipients, and were thereby able to provide more appropriate equipment. Second, they worked closely with the local Panglima Laot, which helped assure that the aid went to people who needed and could use it. Finally, their programs included support for auxiliary facilities to assist with

10 Interview excerpts are identifi ed by the initials of the village name and a sequential transcript number.

11 The Panglima Laot is an adat (customary law) institution in many Acehnese communi-ties, charged with the oversight of custom and ceremonial practices in marine fi shing; man-agement of fi shing areas; and settlement of disputes. The term also refers to the individual who heads the organisation of the same name.

handling and marketing the catch, and for maintenance and repairs and construc-tion of new fi shing boats. These investments have paid off handsomely.

Very few fi sh or shrimp ponds have resumed production in the survey villages;

most are still waiting for the BRR or the provincial government to send backhoes to rebuild the dikes and conduits. A few caged or fl oating pen aquaculture

pro-grams—often established in newly-formed lagoons (suak) where there used to be rice paddies—have been somewhat successful.

Livestock

Livestock is another form of livelihood assistance that has seen some success. Informants’ primary criticisms of livestock assistance have concerned the qual-ity or health of the animals provided; the lack of appropriate skills training and extension services (many of the recipients have little or no experience in raising livestock); and perceived inequality in the distribution of this aid. Again, the more successful programs have involved local organisations—either local NGOs, village cooperatives or ‘community enterprise institutions’ (lembaga ekonomi masyarakat

or lembaga ekonomi gampong, or LEM/LEGA).12

There was the time people were given ducks, but it turns out that all the ducks were the same sex. Well, they’re not going to multiply, are they? Then we were given calves by the government. They were still young, still nursing, but already distrib-uted to the community. I guess people thought that cattle are just like buffalo: you let them go and they take care of themselves. But cows are thin-skinned and need a pen to be safe. Because they were just allowed to roam free, they all died. Somebody should have taught the people how to care for the cattle. (Interview JS-11)

Agriculture

Agricultural recovery has been much slower. In the survey villages, a few com-munities have begun planting small plots of dry-land crops, including market gardens in some of the peri-urban villages. None of the villages has yet had a successful rice crop; most have not even planted rice. Rice paddy rehabilitation has featured prominently in the recovery programs in many of the villages in this survey. According to informants, the most common reason for the failure of these programs has been their timing: more often than not, land clearance work has been completed too late for the planting season, and the fi elds are left fallow.

The following season, they are choked with alang-alang (Imperata cylindrica) grass, and the community is waiting for another clearance project before they will plant. Lack of irrigation is another reason commonly given why people have not yet returned to the paddy fi elds.

Yes, there were some projects to clean up the rice paddies. I forget who it was. They gave us tractors and everything. I think the tractor got stolen. Then, when the land was cleared, it was too late to plant. If you miss the planting season, you aren’t going to get a crop. We can plant in April, or in August if there’s rain. If you plant too late, you get lots of pests too. So, the soil’s all hard again now; not many people want to plant rice. (Interview BM-09)

12 ‘Gampong’ is the Acehnese word for village.

There was a project—they helped with land clearance, seeds and fencing material, but the irrigation wasn’t fi xed. BRR had a project to clear the canals but there was no water, so we couldn’t plant. Now the soil is compacted, and it’s getting overgrown with brush. (Interview UJ-07)

There have been lots of projects, and our land is very fertile. The saying goes: we toss out some seeds, and they grow. We have plenty of good rice paddy land. But now, I’m the only one who’s working the land. If I plant but all my neighbours don’t, it’s hard to get very enthusiastic. All their fi elds are overgrown with brush and grass. My crop will be devoured by rats. (Interview UJ-08)

There’s no way that the rice paddy is going to return to the way it was before, because the soil is mixed with salt water, its fertility is gone. No way are we going to be able to plant rice again. There’s no irrigation, no water supply. It’s rain-fed paddy. What they should do, they should turn it into an industrial park. Then the people need to be trained to work in industry. (Interview JS-13)

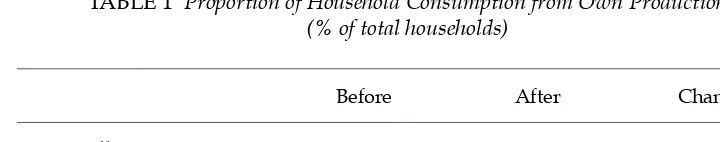

Thus there has been a signifi cant decline in the proportion of food consumed

that households produce themselves (table 1). Some 63% of the 533 households surveyed were producing nothing for their own consumption at the time of the survey, compared with 22% before the tsunami. The majority of the 21% of respondents who answered that ‘most or all’ of their post-tsunami household consumption derives from their own production are from fi shing villages.

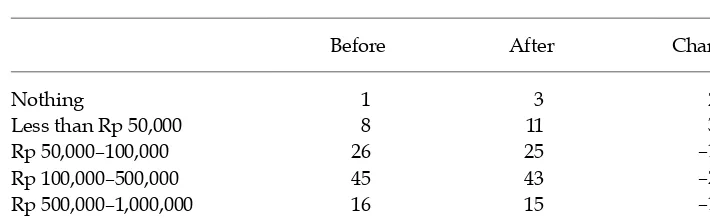

Despite the signifi cant fall in the number of households that produce most or

all of their own food, there has not been a concomitant increase in household expenditures on food (table 2). In fact, the survey results indicate a slight decline. This can be explained by the fact that, at the time of this research, many families in the survey villages were still receiving food aid.

Several informants from various villages quite frankly stated that they do not expect to take up farming again so long as construction jobs are still avail-able. The question of whether food aid suppresses agricultural recovery in post-disaster contexts has been the subject of intense debate for decades.13 It certainly

presents as a likely contributing factor to the delays being experienced in the

13 See, for instance, Srinivasan (1989); Abdulai, Barrett and Hoddinott (2005).

TABLE 1 Proportion of Household Consumption from Own Production (% of total households)

Before After Change

Most or all 46 21 –25

Some 32 16 –16

None 22 63 41

Source: Thorburn (2007).

revival of agriculture in post-tsunami Aceh. Although not specifi cally alluding

to agricultural work, informants in two villages did admit that they intended to remain in barracks, rather than move into new permanent housing, until food supplies ran out.

Aid from the NGOs, enough already! We have things now we never had before. Before the tsunami there were three tractors in this village, now there are six. But nobody wants to work the land. So long as there is aid, and proposals, people won’t work the land, because they keep waiting for the next project. (Interview UJ-08)

In villages that have pre-existing rubber groves not destroyed in the tsunami, rubber tapping is the agricultural activity that is showing the strongest recov-ery. The primary problem has been access. In a few villages, communities have used donor or government block grant funds to construct access roads to rubber groves, allowing production to resume. Several informants in rubber-producing villages told researchers they were happy to return to their previous occupation, as they can earn more in a day tapping rubber than they could as labourers on projects. By contrast, many villagers are choosing not to resume most types of agricultural work so long as more lucrative recovery-related construction work is available. The rubber-tapping example under-scores the importance of agro-ecological diversity, in particular the contribution of tree crops that have been brought back into production relatively quickly after the tsunami. Villages with durian or other high-value fruit crops have similarly benefi ted from the resilience

of these cropping systems.

Small-scale enterprise

Cash grants and other support for small-scale enterprise development have been the most ubiquitous form of livelihood assistance in Aceh, often targeted at women. Nearly every household in each survey village has received at least one allotment of ‘business money’. There are few surprises.

There’s been lots of business money from NGOs. But do you see any businesses here? People don’t look ahead. They’re given money to start a business, but that’s not what they use it for. They buy clothes, motorbikes, fancy hand phones, go sit at the coffee shop. (Interview BL-06)

TABLE 2 Monthly Household Expenditure on Food (% of total households)

Before After Change

Nothing 1 3 2

Less than Rp 50,000 8 11 3

Rp 50,000–100,000 26 25 –1

Rp 100,000–500,000 45 43 –2

Rp 500,000–1,000,000 16 15 –1

More than Rp 1,000,000 3 3 0

Source: As for table 1.

We were given Rp 1,800,000. These days, what kind of business can you start? How is that money supposed to be used for business? (Interview CT-09)

Not long ago, this NGO came and told us they were going to provide Rp 10 million for business money. But then they told us it wouldn’t be 10 million, but only 7.5, because we’d already received some money from Red Cross. But why is it only our village that gets penalised, when the others got Red Cross money too? We decided to turn down the money. So, they said they wouldn’t give us the money, but now people have changed their mind, and say we’ll take the Rp 7.5 million. (Interview UJ-07)

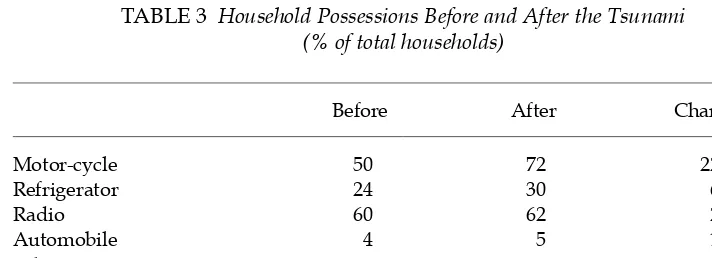

A number of informants told of opening small kiosks or snack shops, but most of these did not last more than a few weeks or months. Most informants were aware of people who had sold ‘livelihood’ equipment and supplies, and many also admitted that they had used cash grants or loans to purchase household goods and food. This is substantiated by changes in the composition of household possessions (table 3). It may appear that ownership of non-productive assets has taken precedence over that of productive ones. In many cases, however, newly acquired motor-cycles are being used for income-generating purposes such as trade, and even when this is not the case, increased mobility and connectivity (through the use of mobile telephones or radios) can signifi cantly increase an

indi-vidual’s productivity.

It was also quite apparent in the survey villages that the majority of success-ful small businesses presently operating were run by people who had had simi-lar enterprises before the tsunami. Most of these businesses have received some assistance in the form of cash or equipment from government, donors or NGOs.

The survey showed that the enterprise development programs that had been most successful—in terms of the proportion of enterprises supported that sur-vived more than a few weeks or months14—were those that included appropriate

skills training and support, and routine follow-up and monitoring.

14 This research did not collect suffi cient data to compare the relative profi tability of dif-ferent types of businesses.

TABLE 3 Household Possessions Before and After the Tsunami (% of total households)

Before After Change

Motor-cycle 50 72 22

Refrigerator 24 30 6

Radio 60 62 2

Automobile 4 5 1

Television 57 56 –1

Sewing machine 24 21 –3

Fishing boat 23 11 –12

Bicycle 62 45 –17

Source: As for table 1.

They check our ledgers and bank account. Also, we have meetings once a week, every Friday. Someone from the NGO comes when we’re having our women’s pen-gajian (religious teaching), and that’s when we meet. (Interview PR-05)

Examples of successful production enterprise development programs include a few sewing groups, salt fi sh production and some handicraft production

enter-prises. The latter have been helped along in some cases by marketing assistance from the sponsoring NGO. Narratives from most survey villages also suggest that women’s enterprises—particularly trade in small household items, prepared food and snacks, as well as some home industry and craft businesses—have a greater success rate than those initiated by men. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that women’s income is more often devoted to supporting children’s education and other family needs than is the case with men’s income.

The sustainability of livelihood support programs is a concern shared by many donors, NGOs and communities. The most common strategy has been the estab-lishment of revolving funds or other forms of micro-credit. Several of these have been set up in conjunction with the village LEM/LEGA or with the Family Wel-fare Association (PKK, Pembinaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga).

We’ve been one of the most successful villages [in] getting people to repay their loans. This is because people are well educated here: they understand about revolv-ing fund credit schemes; [it is] also because of the diligence of the LEM staff. Even so, there are some people who are ‘naughty’, because word has [got] around that this money was a grant, so it doesn’t have to be returned. (Interview JR-07)

LEM/LEGA are intended as an integral element of village government reforms currently under way throughout Indonesia, and are strongly supported by national, provincial and district government policy. Under national decentralisa-tion and village government legisladecentralisa-tion, and reiterated in Acehnese provincial and district qanun,15 village communities are now authorised to establish profi

t-making enterprises to support village government and social and economic development. These can include the commercial exploitation of village assets, such as quarrying of sand or gravel, productive enterprises such as manufactur-ing or post-harvest processmanufactur-ing, managmanufactur-ing a local tourist attraction, or micro-credit schemes for village residents.

One of the most innovative examples from the survey villages is the village government of Darussalam’s plan to purchase a purifi ed water production and

vending facility, which will provide a handy supply of drinking water for village residents (who cannot drink the water from household wells), while generating a healthy profi t for the village. In several of the survey villages, re-establishment of

local markets and resumption of regular market days have provided a signifi cant

boost to local economic vitality.

15 Qanun are Acehnese provincial and district regulations; of particular importance here is the qanun on gampong government, written after Law 11/2006 on Governing Aceh was implemented.

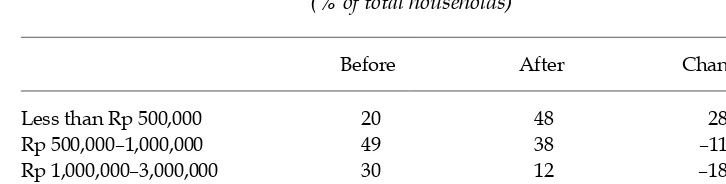

LIVELIHOODS AND HOUSEHOLD WELL-BEING

In terms of household incomes, the survey results show that there has been a general shift of households into lower income brackets since the tsunami (table 4). Overall, incomes were still lower in 2007 than before the tsunami, with a large increase (8%) in the number of households falling into the lowest income bracket (less than Rp 500,000 per household per month, or an annual household income of less than $750).

These shifts were not evenly distributed across the population. The highest income-earners in the survey villages are district government offi cials (who make

up 92% of the top two income brackets). They are followed by teachers, then trad-ers and business owntrad-ers, village government offi cials, craftspersons, drivers, fi

sh-ers, farmers and labourers. Occupational groups reporting an increase in income are district offi cials, teachers, fi shers and labourers, with all other groups showing

reduced average monthly incomes.

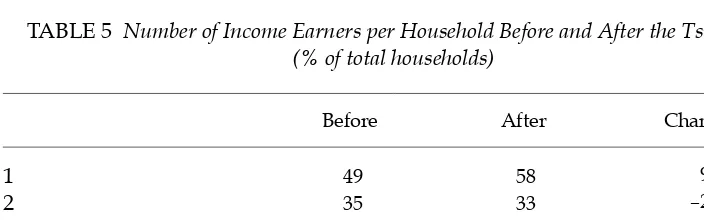

In view of the tsunami’s devastating death toll it is not surprising that house-holds generally now have fewer income earners (table 5), with the average number of income-earning household members falling from 1.8 to 1.6 people per house-hold. This is refl ected in a general reduction in the proportions of households

with multiple income earners, and a large increase in those with only a single bread-winner. In the post-disaster recovery context, most manual labour jobs go

TABLE 5 Number of Income Earners per Household Before and After the Tsunami (% of total households)

Before After Change

1 49 58 9

2 35 33 –2

3 11 6 –5

4 3 1 –2

5 1 1 0

6 or more 2 1 –1

Source: As for table 1.

TABLE 4 Monthly Household Income Before and After the Tsunami: All Households (% of total households)

Before After Change

Less than Rp 500,000 15 23 8

Rp 500,000–1,000,000 44 43 –1

Rp 1,000,000–3,000,000 35 31 –4

More than Rp 3,000,000 5 3 –2

Source: As for table 1.

to adult males, whereas in more ‘normal’ circumstances, several family members can participate in one or more income-earning activities.

The population group that stood out as the hardest hit was single-parent households. Of 533 questionnaire respondents, 55 were widows or female heads of household and a further 24 were widowers or single male heads of household. Their pre- and post-tsunami monthly income fi gures stand in sharp contrast to

the fi gures presented in table 4 above for all households, with nearly half the

single-parent household group falling into the lowest income bracket (table 6). The closing question of the household survey questionnaire asked villagers to compare their current economic situation with their lives before the tsunami struck. Table 7 presents a summary of responses to that question. This presents a very encouraging scenario. It remains to be seen whether this trajectory can be maintained, as the ‘aid tsunami’ recedes.

CONCLUSION

The ACARP research found that, in general, household basic needs were being met in all the survey villages. Household incomes had dropped since the tsunami, as had the average number of income-earners per household. However, two and a half years into the recovery, many households’ incomes had recovered to pre-tsunami levels, while the remainder were at least meeting basic needs. Nearly one-third of households in the survey villages reported that their economic situ-ation was better than it had been before the tsunami. This resulted from a com-bination of factors, many of them temporary in nature—for example, remaining food aid and subsidies, casual work as labourers on construction projects or sup-plying construction materials, and the use or conversion of livelihood assistance

TABLE 6 Monthly Household Income Before and After the Tsunami: Single-parent Households

(% of total households)

Before After Change

Less than Rp 500,000 20 48 28

Rp 500,000–1,000,000 49 38 –11

Rp 1,000,000–3,000,000 30 12 –18

More than Rp 3,000,000 1 1 0

Source: As for table 1.

TABLE 7 Current Household Economic Situation, Compared with Before the Tsunami (% of total households)

Worse than before 36

About the same 34

Better off now 30

Source: As for table 1.

for consumption purposes. Productive and ‘normal’ commercial activities were resuming, though still quite limited in scope and scale.

A signifi cant (though not quantifi able) proportion of livelihood assistance had

been used for household consumption, including the purchase of luxury goods. Already, large numbers of motor-cycles had been repossessed by vendors when the purchasers could not meet payment schedules. There was a robust market in tools and equipment that had been provided to villagers for livelihood promotion.

The most common criticisms and complaints about livelihood aid focused on quality or appropriateness: size or type of materials, equipment or stock provided (shoddy boats that were either too large or too small or under-powered; young, unhealthy animals; complicated and unwieldy ‘appropriate technology’ stoves and dryers); the lack of follow-up extension and support; and issues of targeting and equity. Programs that endeavoured to engage local ‘experts’ (the users them-selves, community leaders and customary [adat] authorities) in the planning, dis-tribution and subsequent management of inputs had proven far more successful.

A signifi cant factor differentiating successful and unsuccessful livelihood

pro-grams was the degree and type of follow-up guidance and support that program benefi ciaries received. Livestock extension and veterinary services were singularly

lacking. Business development guidance and support, along with monitoring and

fi nancial audits, proved to be extremely useful in the minority of cases where they

had been provided. Marketing assistance was keeping some handicraft programs afl oat, though much of this appeared to target an international ‘sympathy market’,

and thus was probably not sustainable. There is, however, a good local market in Aceh for locally produced gold thread embroidery, and NGO marketing assistance, even if only temporary, probably helped a few producer groups get re-established. Small-scale fi sheries were showing good recovery, despite copious examples

of inappropriate, poor quality or misdirected aid. Again, the communities where this had been most successful were those where local fi sher groups and

custom-ary organisations (Panglima Laot) had been engaged in administering the aid and managing its use. Supporting amenities such as fi sh landing and processing

facili-ties, facilities and equipment for local organisations and, most importantly, tools and facilities to allow the resumption of local boat building and maintenance industries greatly contributed to the success of a few of these ventures.

At the time the survey was undertaken, agricultural recovery was barely getting under way in most survey communities. Numerous factors contributed to this. Most commonly cited were tsunami sediment and debris that still covered fi elds;

lack of irrigation and drainage; an increase in pest (rat and wild boar) populations since the tsunami; and the fact that nobody else was returning to the fi elds.16

16 This picture of slow agricultural recovery was accurate at the time of the survey. How-ever, as this article goes to press (over one and a half years since the fi eld research was completed, and just over four years into the recovery process), a majority of the farmland damaged in the tsunami has been replanted, and some 15,000 hectares of fi shponds have been restored. Agricultural production in Aceh surpassed pre-tsunami levels by 5% in 2007 (World Bank 2008a). Tsunami recovery assistance (and the cleansing of saline soils through three rainy seasons) constituted only part of the reason for this recovery: the end of the 30-year armed struggle between GAM and Indonesian security forces in August 2005 also allowed Aceh’s large estate crop sector to resume production.

Evidence from interviews supported the hypothesis that most people were not returning to the fi elds simply because there were still easier ways of putting food

on the table. Residents of communities where access to agricultural land was an issue—such as relocation villages or villages that lost a large proportion of land to submersion or salt-water intrusion—expressed concern over what would happen to them after the post-tsunami construction boom ended.

The agricultural activity that was showing the best signs of recovery was rubber tapping. It could be resumed as soon as people gained access to existing groves, and they could earn more from this activity than from a similar expenditure of labour in construction work. Rubber’s rapid recovery under-scores the impor-tance of agro-ecological diversity, and the critical role of tree crops in household production strategies. The primary form of outside assistance that supported the resumption of rubber production was village road construction. By contrast, most other types of agricultural assistance provided in post-tsunami areas—seeds, fer-tiliser, equipment and credit—were premature.

Small-scale enterprise development also showed quite uneven results. Most often, the successful examples were grants and loans that allowed individuals to re-establish enterprises they had owned or managed before the tsunami, such as fi shing, fi sh processing and marketing, petty trade, food services, vehicle and

equipment repair, construction and contracting. There were smaller numbers of successful start-up businesses as well—often conducted by widows who received assistance to develop small marketing or productive enterprises.

In general, women’s micro-business endeavours were proving more successful (in terms of their survival rate) than those started by men. Anecdotal evidence suggested that women’s income was more often devoted to supporting family needs than was that of their husbands and sons.

Cooperatives and other forms of group ventures had begun to succeed in a few cases, though not in others. Again, women’s groups (in handicrafts, fi sh

process-ing and marketprocess-ing) generally worked together better than those of their male counterparts (farmer groups, ownership collectives for tractors or construction equipment)—with the sole exception of fi shermen’s groups. The success of the

latter is explained by the fact that co-operative ownership of fi shing boats and

equipment was commonly practiced in some parts of Aceh before the tsunami. Many informants were critical of the insistence by some donors and NGOs that eligibility for livelihood assistance be dependent on the establishment of groups, suggesting that these ‘artifi cial’ assemblages had little chance of surviving beyond

the initial distribution of aid—since many members would have signed on only to be eligible for the aid. Where there are effi ciencies or economies of scale to be

gained by producing or marketing collectively, they suggested, this tends to occur spontaneously.

LEM/LEGA groups represent a potentially important form of collectively owned enterprise established in a few of the survey villages (and they are to become a feature of all villages according to national, provincial and district policy and regulations). Under post-reformasi village government reforms, duplicated in the 2006 Law on Governing Aceh and in numerous provincial and district qanun, village communities are encouraged to establish profi t-making enterprises to

sup-port village government and social and economic development. Village-owned enterprises, cooperatives and micro-credit programs all have a very uneven track

record in Indonesia, and it is clearly too early to ascertain whether the scores of post-tsunami institutions and schemes of this kind will become self-fi nancing and

sustainable in the long run (and, if so, whether they will have any lasting impact on poverty alleviation).

Some villages’ economies were rebounding much more quickly than others. This was due to a wide variety of factors, including location (relative proximity to cities or towns, location on or away from major highways); the relative degree of tsunami damage; the existence of particular types of enterprises that could be revived quickly (for example, brick production, fi shing, rubber tapping, cigarette

wrapper production); and the effectiveness of particular aid interventions. A fundamental fl aw characterising much livelihood aid in Aceh was its lack of

imagination—as exemplifi ed by the preponderance of sewing, baking and

embroi-dery programs for women, and by donors’ passion for micro-credit and revolving fund programs. This sort of supply-driven economic development programming was largely taking place without any analysis of markets or of new economic opportunities being created by changes occurring in Aceh and across the region. Acehnese villagers demonstrated considerable savvy in identifying and exploit-ing opportunities created by recovery aid and its multipliers—as demonstrated by their rational choice to maximise household incomes through construction and contracting work rather than return to agriculture, which picked up only as con-struction work began to taper off. Donor-supported livelihood programs in the future could benefi t from a similarly adept reading of Aceh’s changing economic

landscape.

REFERENCES

Abdulai, A., Barrett, C.B. and Hoddinott, J. (2005) ‘Does food aid really have disincentive effects? New evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa’, World Development 33 (10): 1,689–704. Adams, L. and Winahyu, R. (2006) Learning from Cash Responses to the Tsunami: Case Studies,

Humanitarian Policy Group, Overseas Development Institute (HPG–ODI), London. Bappenas–CGI (National Planning Agency and Consultative Group on Indonesia) (2005)

Indonesia: Notes on Reconstruction: The December 26 2004 Natural Disaster, Bappenas, Jakarta.

BPS (Central Statistics Agency) (2004) Indonesia Human Development Report 2004. The Eco-nomics of Democracy: Financing Human Development in Indonesia, BPS-Statistics Indo-nesia, Jakarta.

Chambers, R. (1987) ‘Sustainable livelihoods, environment and development: putting poor rural people fi rst’, IDS Discussion Paper No. 240, Institute of Development Studies, Brighton.

Chambers, R. (1995) ‘Poverty and livelihoods: whose reality counts?’, Environment and Urbanization 7: 173–204.

Chambers, R. and Conway, G.R. (1991) ‘Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century’, IDS Discussion Paper No. 296, Institute of Development Studies,

Brighton.

DFID (Department for International Development) (1999) Sustainable Livelihood Guidance Sheets, Department for International Development, London.

Doocy, S., Gabriel, M., Collins, S., Robinson, C. and Stevenson, P. (2006) ‘Implementing cash for work programmes in post-tsunami Aceh: experiences and lessons learned’, Disasters 30 (3): 277–96.

Kuncoro, A. and Resosudarmo, B.P. (2006) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies 42 (1): 7–31.

Oxfam (2005) ‘Back to work: how people are recovering their livelihoods 12 months after the tsunami’, Oxfam Briefi ng Paper No. 84, Oxfam, London.

Srinivasan, T.N. (1989) ‘Food aid: a cause of development failure or an instrument for suc-cess?’, World Bank Economic Review 3: 39–65

Telford, J., Cosgrave, J. and Houghton, R. (2006) Joint Evaluation of the International Response to the Indian Ocean Tsunami: Synthesis Report, Tsunami Evaluation Coalition, London. Thorburn, C. (2007) The Acehnese Gampong Three Years On: Assessing Local Capacity and

Reconstruction Assistance in Post-tsunami Aceh, Report of the Aceh Community Assistance Research Project (ACARP), Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), Jakarta, available at <http://www.indo.ausaid.gov.au/featurestories/acarpreport. pdf>.

Thorburn, C. (2008) Village government in Aceh, three years after the tsunami, Paper presented at the UC Berkeley–UCLA Joint Conference ‘Indonesia: Ten Years After Suharto’, Berkeley, 25–26 April, available at <http://repositories.cdlib.org/cseas/ CSEASWP1-08/>.

World Bank (2006) Aceh Public Expenditure Analysis: Spending for Poverty Reduction and Reconstruction, The World Bank, Jakarta.

World Bank (2008a) Aceh Economic Update, October 2008, The World Bank, Banda Aceh. World Bank (2008b) ‘Aceh tsunami reconstruction expenditure tracking update: April 2008’,

The World Bank, Banda Aceh, accessed 6 November 2008 at <http://www.docstoc. com/docs/1002818/Aceh-Reconstruction-Finance-Update-Dec>.

APPENDIX 1

THE ACEH COMMUNITY ASSISTANCE RESEARCH PROJECT (ACARP)

The Aceh Community Assistance Research Project (ACARP) was a multi-donor supported endeavour to identify and assess the main drivers of recovery in tsu-nami-stricken communities in Aceh. The study focused on providing an under-standing of the social, economic and governance institutions in tsunami-affected villages during two and a half years of recovery, and of village communities’ capacity to overcome problems and rebuild their lives. It sought insights from Acehnese village communities into the impact and effectiveness of various recon-struction assistance strategies, programs and inputs in helping them to rebuild. In short, ACARP was an attempt to comprehend and communicate village com-munities’ own perceptions of progress, constraints and the value of external assistance.

Initial support was provided by the Australia–Indonesia Partnership for Reconstruction and Development (AIPRD–AusAID). The Partnership was soon joined by several other agencies in the formulation of the project: BRR, UNDP, the World Bank, Oxfam, Muslim Aid, Catholic Relief Services, AIPRD–LOGICA (Local Governance and Infrastructure for Communities in Aceh) and Syiah Kuala University in Banda Aceh. Each of them committed resources, oversight and guidance. Representatives of these organisations formed the ACARP Project Steering Committee, to set goals and targets, review progress and discuss fi ndings

and recommendations.

ACARP’s total budget was just under $200,000, not including the considerable ‘in-kind’ logistical support (such as offi ce space and equipment, and transport

for researchers) from several supporting agencies. The project structure consisted of a Team Leader and two administrative and logistical staff, a Senior Research Advisor, a Training and Project Design Advisor and a Senior Field Researcher, plus 27 fi eld researchers nominated or seconded by Steering Committee

member organisations. Three volunteer interns also assisted with secondary data collection and analysis; one of these was also able to visit research teams in the fi eld. An ACARP Peer Review Network of interested practitioners and

academics was established to review and refi ne research tools and survey

instruments, initial research fi ndings and report drafts. Overall research design

and fi nal report writing were the responsibility of the Senior Research Advisor,

Craig Thorburn.

Field research took place over a two-month period in mid-2007, interspersed with periods of intensive discussion and analysis involving the full research team. The research was conducted in 18 villages—from a total of 866 villages in Aceh that were heavily damaged by the tsunami—located in the most severely tsunami-affected districts of Aceh Barat, Aceh Jaya and Aceh Besar. Villages were selected in ‘matched pairs’ of adjacent or proximate villages that shared many characteristics in terms of physical and environmental features, socio-economic profi le and level of tsunami damage. Each pair included one village

that appeared to be recovering much more successfully than its ‘twin’. Pairs of villages were chosen to represent a variety of socio-economic settings, for example, agricultural villages, villages that depended more on fi shing, remote

or isolated villages, peri-urban villages, high or low confl ict-intensity villages,

and villages that had to relocate. The total (surviving) population of the ACARP

survey villages was 12,373, with individual village populations ranging from 140 to 2,686.17

Field research outputs included the following:

533 household questionnaires 298 interview transcripts

54 focus group discussion transcripts 35 case studies

52 family histories 18 village profi les

Of the questionnaire respondents 42% were female; women constituted 30% of interviewees and 34% of focus group participants. Interview and focus group dis-cussion transcripts ranged in length from one to 13 pages.

The fi nal report was written during the months October to December 2007. The

results were then disseminated in a series of seminars and workshops held in the three districts where the research took place, and in Banda Aceh and Jakarta.

17 The post-tsunami population of Aceh was 3,930,000. According to BRR statistics, 866 villages, comprising 26,224 households, were completely destroyed or heavily damaged in the tsunami. Other estimates are considerably higher; for example, early donor and Indonesian government reports listed the number of people displaced by the tsunami at over 700,000 (Bappenas–CGI 2005).